Pointing out the obvious

And other less obvious things I found on the net this week

The Retrospectoscope: a rare and delicious sighting

It was just Wednesday this week when I was pushing back on someone praising this paper on Government, where it’s going wrong and what to do about it. Of it’s kind it’s actually pretty good. But, on a quick squiz, I said this:

There are some bad signs. … One of my standard tests of this kind of literature is “does it acknowledge similar stuff written in the last decade or so, explain what it thinks of it and why it hasn’t succeeded” — because as we all know these kinds of critiques are always doing the rounds. Alas it doesn’t.

This puts me in mind of collaborating on a Cabinet Submission with some folks in PM&C about seven years ago. It addressed a particular area of social disadvantage. It began with aspirational words to the effect that the policy must be efficient, effective and equitable. Or as Greta Thunberg might say, blah, blah, blah.

I didn’t make much progress on what was bugging me until I was in the shower the next morning, after which I wrote this (It’s lightly edited to improve readability):

What follows from the fact that we’ve had something like 40 inquiries and ‘new starts’ around the states over the last 15 years or so – all of which would have looked reasonably like the initial draft of our document? We will just do what all our forebears have done. We’ll end up back at business-as-usual unless the approach is predicated on the frightening proposition that we don’t know how to do it.

If we did 40 inquiries and presumably about half that number of fresh starts, you’d think that would have turned up some big finds. But it hasn’t.

So the way I’ve amended the first half of the doc is predicated on the idea that the system will simply keep going through the great cycles and epicycles of business-as-usual unless it’s understood that it starts from a different set of premises, and they are that:

We do not know how to solve these problems

We do not have good evidence on programs that work

We have not developed good approaches to experimenting in the field and documenting highest impact strategies and that therefore

We need a first phase of the program which targets safe, small scale experimentation, learning, and validation and extension of that learning.

It’s only in the context of that that a second more conventional phase can be entered in which competition between service providers might play some role — when we’ve got enough understanding to hold them accountable.

In order to have competition make sense you need to be able to set the rules of the game, but the fact is we don’t know how to set those rules without them becoming part of the problem.

In fact one of the things that keeps this approach going is the relentlessly forward looking nature of all the analysis that goes into it. People turn up with the same basic ideas — devolve power more, give users more say in how the program is run etc, with everyone blissfully unaware of the fact that these things are easy to say, and have been said — again and again. As if rehearsing what we want, gets us much closer to working out how we are going to do it.

And so I read the article below by Paddy Gourley in the very terrific Inside Story with real delight. It begins talking about the amalgamation of “Centrelink, Medicare and much more” into the newly minted Department of Human Services with 37,000 staff. In 2012 DHS submitted itself to a “capability review”.

[It] concentrated on leadership, strategy and delivery. It was proudly “forward looking,” “short and sharp” and took a bird’s eye view. It concentrated “primarily on the views of senior leadership” although with a little consultation with “external stakeholders.” Superficiality was inherent in the process.

So the review’s recommendations, while possibly helpful, were mainly vague and unmechanical. “Operate as a high-performing team,” it admonished, foster “more open communication,” be “pro-active in enabling a unified… culture,” develop a “concrete service design map,” “move from a transactional view to a holistic view” and “place the customer at the centre.” Well why not?

The review provided a rosy view of the DHS, which it reckoned could “be a significant contributor to good policy outcomes.” It also said that the department was blessed with “a highly capable Secretary, who is widely respected and well skilled to lead the department into a challenging future.”

That secretary was Ms Kathryn Campbell, whose minister later became that self-proclaimed tough welfare cop, the Hon Scott Morrison. Together they brought forth robodebt, whose consequences have been graphically described by the Holmes royal commission and in Rick Morton’s book, Mean Streak. It’s a story that has at its heart undiluted political and bureaucratic careerism on which no restraints have yet been imposed.

In 2019, the functions of the DHS were placed in Services Australia, or SA, an executive agency that is neither fish nor fowl. It isn’t a department, and it isn’t a statutory authority; it’s something in-between. Now this new agency has had its own capability review, a procedure dropped by the last Coalition government but now revived.

The SA review, whose undated report was posted on the Public Service Commission’s website on 29 January, was conducted by David Thodey a semi-ubiquitous reviewer for the Commonwealth, Cheryl-ann Moy, a facilitator and coach, and senior officers from the Tax Office and the Parliamentary Services Department. It was supported by staff from the Public Service Commission.

On the evidence of this report, the review methodology doesn’t seem to have changed much since 2012. Its “framework” is an “excellence horizon,” which tries to describe which capabilities are needed, and gaps in “core domains” listed as “Leadership and Culture, Collaboration, Delivery, Workforce and Enabling Functions.”

Like its predecessors, the review professes to be “forward facing” and doesn’t offer what it calls “critiques of the agency’s past performance.” Yes, better not cast a cold eye on the ogre in the room, robodebt: presumably that would awkwardly complicate matters and, it might be supposed, we all might need to “move on.”

Anyway, Thodey and his associates interviewed forty “stakeholders,” ran eleven staff workshops, sent out a staff survey that snagged a slim 18 per cent response rate, visited a couple of offices and did some “desk top research.” That done, they presumably left the staff at the Public Service Commission to give them a draft report.

The resulting eighty-page document is excruciating. It swarms with clichés and platitudes mixed into a dispiriting cascade of managerialist mumbo jumbo. Sensitive readers might be reaching for the hemlock at about the halfway mark, or even earlier.

Without wanting to rub it in, and to adapt the honeyed words of a literature Nobel prize winner brought back into vogue by a recent film, the report spends too much time playing on the penny whistle and poisoning us with words.

It is suffused with brain bruising notions such “agility,” “convergence,” “pro-activity” of course, “customer focus” and “customer-centric,” “overarching strategy,” “co-design,” “alignment and prioritisation” (which is being “driven”), “escalation pathways,” a “pro-active posture,” “customer relationship management tools,” “master program tribes,” “oversight mechanisms,” “collective vision” and on and on.

The review allocates marks on nineteen elements within the “core domains” specified by the prescribed methodology. Four of these elements are regarded as “embedded,” fourteen “developing” and one “emerging.” The relationship of this categorisation to evidence is opaque.

Anyway, the review says SA should focus on “enhancing the customer experience, improving the quality of government services, continuing organisational strategy development and driving cultural change and advancing digital and technological capabilities.”

On “capability uplift,” it’s suggested that SA align “the service delivery business to the agency’s vision,” get senior staff with the right skills, develop a “culture of trust internally” and get the skills and capabilities needed in “a digitally enabled world.” Could SA have been unaware of these high level imperatives? If it wasn’t, it’s now been told. …

The head of SA, David Hazlehurst, has welcomed the review. Like Kathryn Campbell in 2012, he says it has come at a “pivotal” time and promises to get on with following its advice.

It’s to be hoped he does a more convincing job than Stephanie Foster, the head of the Department of Home Affairs, who following a capability review of her department brought forth a document titled “Transformation Action on a Page.” It was distinguished by notable inanities including the promises of a “sophisticated foresighting capability” and offering “industry a ‘single window’ and the community ‘no wrong door.’” …

So how might capability reviews be made more useful?

Lawrence Lessig is being overdramatic. Or maybe he’s not.

Is economics in a mess? Nat Dyer says ‘yes’

Economists mistaking their models for the real world? Surely not.

I’m shocked, SHOCKED that that has been going on and certainly think we should round up the usual suspects. Still I have to admit that this is an argument I’m no stranger to. It turn out I’ve even made it myself.

Here’s another book which tracks this phenomenon — which Schumpeter called the Ricardian vice — all the way back to Ricardo.

I think Ricardo’s discovery of the logical structure of the ‘law’ of comparative advantage was a landmark in social science — the discovery of something that Samuelson used as an example of a law-like discovery in social science which was both true and not obvious. I use Ricardo for instance to show why most taxes are not a tax on competitiveness even as our ‘commonsense’ insists that they impose costs on exporters and those competing with imports. (They’re not because what matters is relative domestic comparative costs, not absolute costs.)

In that context it doesn’t matter that Ricardo’s model is not a complete model of all the aspects of trade. What he’s done is captured the essence of its logic which insists that, in so far as prices matter for trade, the prices that matter are not absolute prices on the world market, but divergences in the domestic price relativities of the relevant trading partners.

If that sounds confusing, think about it this way: when England imports port from Portugal and exports cloth to Portugal, this is not (necessarily) because England produces cloth at absolutely lower costs than Portugal (though it may) nor does Portugal export wine because it can produce that at absolutely lower cost (though it may). Instead, what gets Portuguese port to England is that there it can be traded for more cloth than it can in Portugal, and vice versa if you’re trying to turn cloth into port — which you do if you run a London club and your members are weary of sherry.

Note it is a misnomer to call this a ‘model’. It’s an abstraction of a particular logic applied to a situation and the situation could have all kinds of extraneous details and yet the logic would continue to hold. That isn’t a prediction that the logic would produce any given result because other factors could be more important. But the logic itself would be operative, even if not determinative.

Economists generally don’t appreciate the point. (Or if they do in principle, they rarely do in practice). Starting with Ricardo, they got rather over-excited about the potential of this new method. It was truly a great idea for following through a particular train of thought — no more nor less. But of course it became more than this. It became a ‘theory’ of trade. And Ricardo had a similar theory of land rent, and of agricultural productivity. They were great ideas too. But that’s all they were — a drawing out of a particular logic of inquiry to its logical conclusion.

Ricardo — I’m presuming he was on the spectrum — went a bit overboard with all this — hence Schumpeter’s term “the Ricardian vice”. Then as the 19th century proceeded, economists saw its problems and dialled back the enthusiasm. But then as the ‘marginalist revolution’ took hold from 1870 on, they dedicated themselves to the tempting, but ultimately silly idea that something is more ‘scientific’ if it’s more mathematical. And we ended up in a tower of Babel that Paul Krugman and I disagree about (He’s keener on it because he helped build it.)

Anyway, over to Nat.

The book's argument is that in straining to peer through the chaos and confusion of the world to the underlying mechanisms, too much economic thinking, both in Ricardo’s day and ours, mistook a small, unrepresentative sample as the whole picture. This has distorted the vision of generations. If your scientific ideal is a simple, logical model, there is a tendency to focus on those parts of reality that are more regular or can be easily counted. The awkward aspects more difficult to capture in formal laws or mathematics—the fact that humans are a diverse group of emotional and social primates, for example, or the natural, political, and legal contexts in which markets are born and function—tend to get filtered out, set apart, and eventually forgotten. One physicist-turned-financial modeller, Emanuel Derman, has compared the process of creating a model to forcing the ugly sisters’ feet into Cinderella’s glass slipper by cutting off the toes or heel (as in early versions of the tale). Whatever does not make it into the elegant slipper often disappears in the mind’s eye and some begin to say it never existed at all.

The pay-off, once you’ve hacked these awkward parts off (and added some new features), is big. At the centre of this new theoretical world is an imaginary creature, known as a ‘rational actor’ or ‘economic human’, that has an order and regularity that is a scholar’s dream. You can ask your model all sorts of questions and if you’ve set it up correctly, it will give you amazingly precise answers. But too few economists have weighed carefully the costs and benefits of the approach.

The main cost, I want to convince you, is that the questions seeming being studied are quietly replaced with different, easier, less relevant ones. This problem-solving strategy is called ‘substitution’. There is nothing necessarily wrong with the method. If the easier problem incorporates the essential features of the more complex one, it can provide insight. Substitution can be used to create a quick, rough-and-ready answer to a difficult or even impossible question. … The trouble begins, however, if the simpler world is not a good analogy for the real one. It is made worse if researchers fail to communicate clearly that a substitution or swap has been made and the answers are used uncritically to guide actions in the real world. It becomes most dangerous when people start to fall in love with the simple model and see it as the real, hidden truth behind the events of the world. This, as we’ll see, is called the Pygmalion Syndrome. In the final stage, when events or actions violate the imaginary model, the true believer will keep faith with the substituted reality and try to alter the world to match it. This has happened time and again, often with disastrous consequences.

Don’t believe him

Ezra Klein being very clever and very schmick. (Though he repeats himself rather a lot). If you want to read it and don’t have a NYT subscription, Inside Story has the … well the inside story.

Trump: On the one hand Paul Krugman

And on the other, Andrew Sullivan

Above all: do not make this a binary choice. If you do, Trump wins. Make it multiple choice, and he loses half the time. Focus on where Trump is vulnerable. Yes, on egregious violations of the law, or incompetence, call him out immediately. That’s how the spending freeze was unfrozen; that’s why Grassley and Durbin are already telling Trump to obey the law on his firing of Inspectors General. Judges are mobilizing. And this is how it is supposed to work. The Founders understood that the energetic executive they wanted could also over-reach. The Congress and courts were their solution. This is not the end of democracy. It’s just a testing period.

So take a breath. Part of the shock and awe of Trump’s first weeks was designed to disorient, and provoke the kind of breathless response we’ve seen. If we’ve learned anything this past decade (it appears the Dems and the MSM still haven’t), we shouldn’t oblige him. As Carville says, let Trump knock himself out. Wait until inflation rises with tariffs, until the Bannon-Broligarch battle gets hot, until Bondi makes a mistake. You get the picture.

Of course, I understand why emotions are high. But I also recall how emotions can cloud judgment, prevent effective opposition, and degenerate into mindless social media hysteria. It happened to all of us eight years ago — including me at times — and it failed. Time to change tack. Time to make distinctions. I’m sure I’ll screw up along the way, but, with your help, I’m going to chart a more discriminating and strategic path here on out. Let’s hope the Democrats get the message.

Cher: unaffected after all these years. A good doco

A reader of this newsletter and good friend of mine was in the Tate Modern (I think) in London and got talking to someone who he ended up having a cup of tea with. She was very nice — and so is he. They got on well. My friend realised some time later than it was Cher.

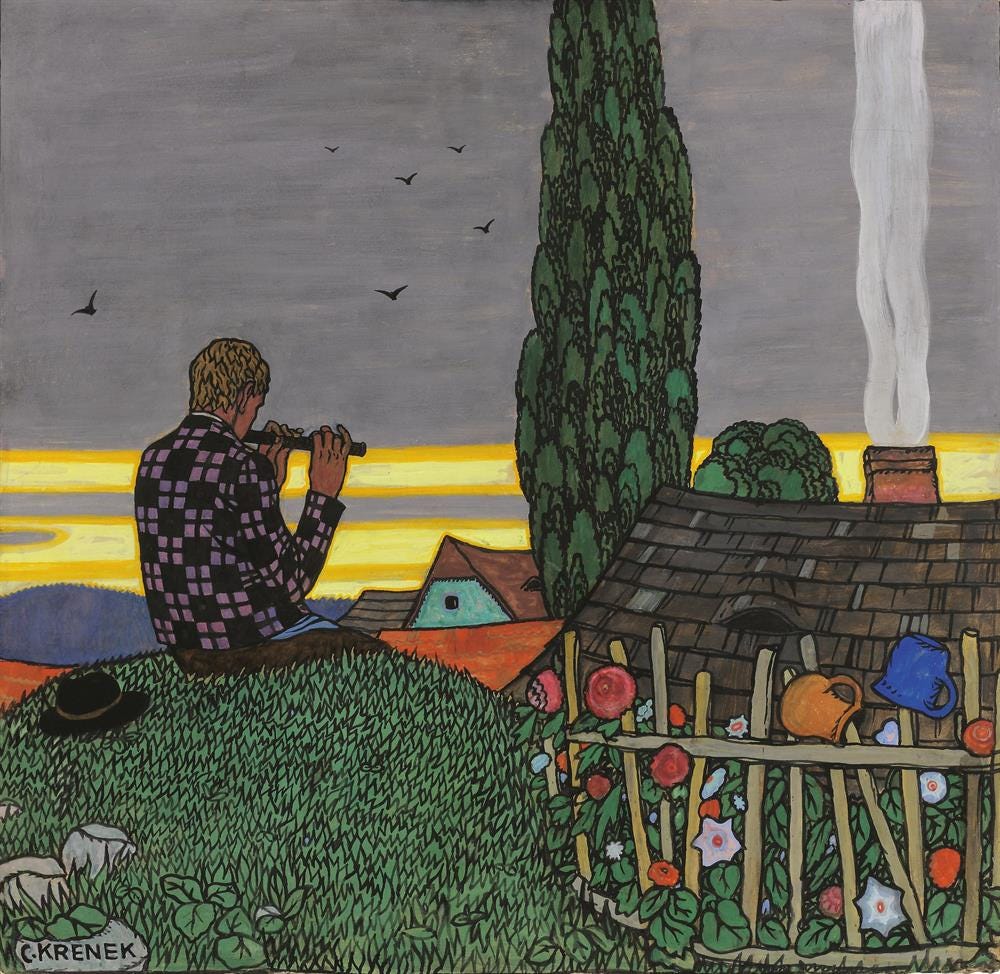

Carl Krenek

Martin Wolf points out the obvious

Sometimes you have to

Sad that it has to be pointed out, but there you go. We live in strange times.

In Trump’s view, running a trade surplus with another country is a “ripoff”. This is of course the reverse of the truth: such a country provides a greater value of goods and services to US customers than it receives from them. Its residents will either be using this surplus to pay countries with which it is running deficits or be accumulating financial claims, mainly upon the US, because the US is a safe place to invest in and issues the world’s reserve currency. A way to reduce US trade deficits then would be to cease providing highly regarded assets. The inflationary impact of Trump’s fiscal and monetary policies might even achieve that. Yet Trump is determined to retain the dollar’s reserve status. Paradoxically, then, he wants the dollar to be both weak and strong.

Trump’s naive focus on bilateral balances rather than the overall balance (unlike the mercantilists of old) is ridiculous. But it is a reality. So, he is using the threat of tearing up the US -Mexico-Canada Agreement he concluded in his first term to impose penal tariffs. Astonishingly, these tariffs are to be much higher on Canada, with which the US has the longest unguarded border in the world, than on China, its proclaimed enemy. In any case, we now know that being a close ally will not influence Trump. Like any bully, he will menace those he considers weak. It might not end there. Sounding like Vladimir Putin on Ukraine, he has indicated he would like to annex Canada. This is a sick joke. Why would Canadians, with far higher life expectancies and lower murder rates, wish to become Americans?

A crucial objection to what Trump is doing is the uncertainty he creates. The decisions by Canada and Mexico to enter a free trade agreement with the US, just like other countries chose to open their economies within the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the World Trade Organization, were bets on policy stability. This is important for countries, especially small ones, and vital for businesses betting on reliance on foreign markets and integration into complex supply chains. Even unfulfilled threats are damaging. An inconsistent US is an unreliable partner: it is that simple.

It was not always so. Before Trump killed the WTO dispute settlement mechanism in 2019, countries used to bring and win cases against the US. The rules-governed order was not a fantasy. But it is now — thanks to Trump.

The economics are at the heart of Trump’s abuse of the tariff weapon. But it is about far more than economics. The unpredictability of the US affects every aspect of its international relations. Nobody can count on it, be they friend or foe. So, nobody can make plans based on reliable assumptions about how it will behave in future. It is possible that some allies will decide that, although they prefer the US, China is at least more predictable. That would be an insane position for these countries to be in. But it would be the almost inevitable result of Trump’s gangsterish approach to international relations.

Substack: what’s it up to?

The co-founder of Substack explains what he’s about. (While we all wonder if, how and when what is a marvellous new development in our lives, might be enshitified.)

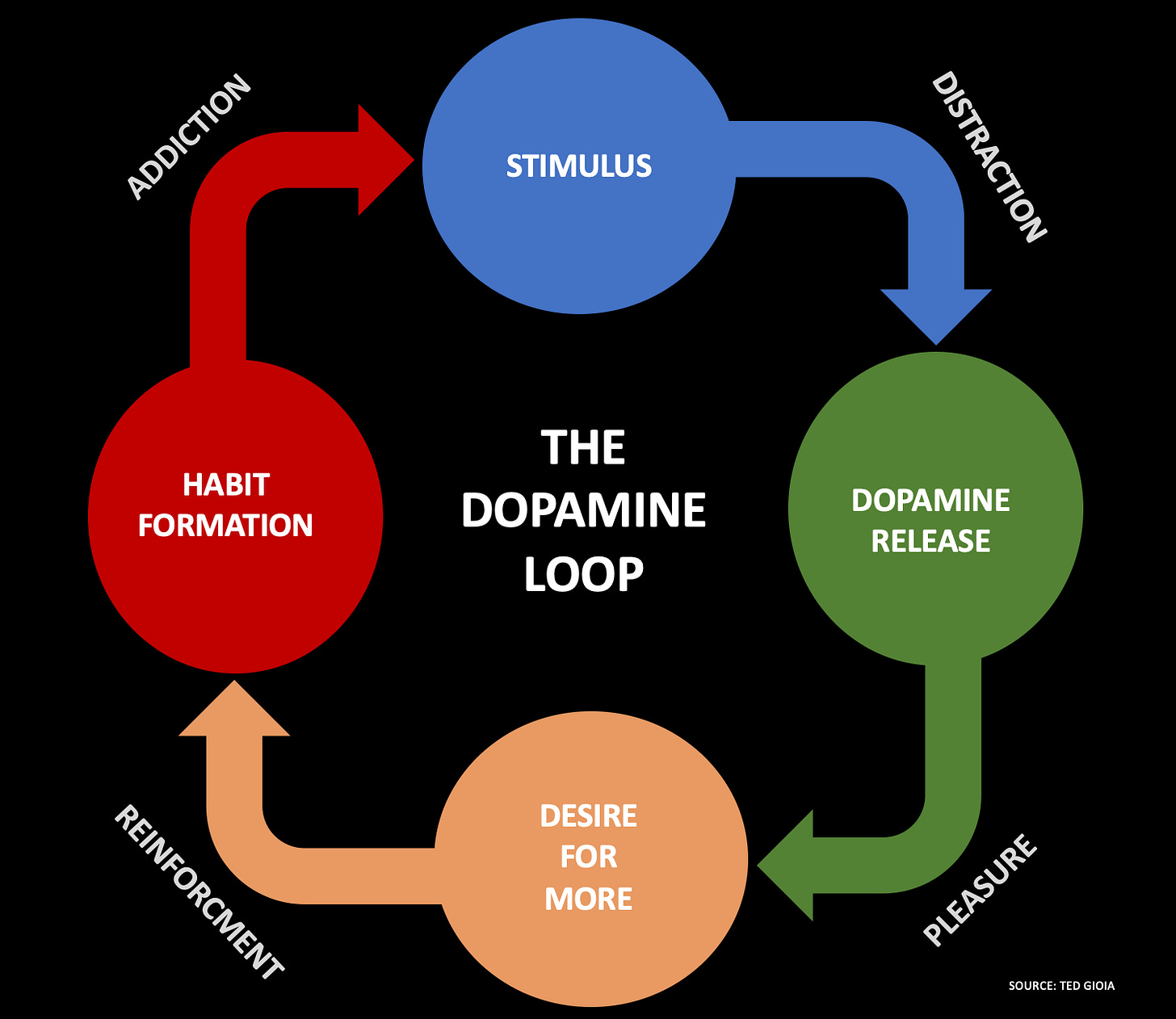

Ted Gioia on Our Current Predicament

The illustrations are pretty self-explanatory, so I’ll just present them here and you can go to the full article if you want. HT: Annabel for the link.

If the culture was like politics, you would get just two choices. They might look like this.

But …

Sarah O’Connor on what’s fair online

Sarah O’Connor usually writes good columns. As here.

I woke up one morning in November to discover that I could no longer access [my gmail account]. … I had not sent any spam and couldn’t imagine why Google’s algorithm thought that I had [violated Google’s policies]. That made it hard to know what to write in the “appeal” text box, other than a panicked version of something like, “I didn’t do it (whatever it is)!” and, “Please help, I really need access to my email and my files”. …

Two days later, I heard back: “After reviewing your appeal, your account’s access remains restricted for this service.” I wasn’t given any more information on what I had supposedly done or why the appeal had been rejected, but was told that “if you disagree with this decision, you can submit another appeal.” I tried again and was rejected again. I did this a few more times — curious, at this point, about how long this doom loop could continue. A glance at Reddit suggested other people had been through similar things. Eventually, I gave up. (Google declined to comment on the record.)

Among regulators, one popular answer to the question of how to make automated decisions more “fair” is to insist that people can request a human to review them. But how effective is this remedy? For one thing, humans are prone to “automation complacency” — a tendency to trust the machine too much. …

Ben Green, an expert on algorithmic fairness at the University of Michigan, says there can be practical problems in some organisations, too. “Often times the human overseers are on a tight schedule — they have many cases to review,” he told me. “A lot of the cases I’ve looked at are instances where the decision is based on some sort of statistical prediction,” he said, but “people are not very good at making those predictions, so why would they be good at evaluating them?”

Once my impotent rage about my email had simmered down, I found I had a certain amount of sympathy with Google. With so many customers, an automated system is the only practical way to detect breaches of its policies. And while it felt deeply unfair to have to plead my case without knowing what had triggered the system, nor any explanation of pitfalls to avoid in an appeal, I could also see that the more detail Google offered about the way the system worked, the easier it would be for bad actors to get around it.

But this is the point. In increasingly automated systems, the goal of procedural justice — that people feel the process has been fair to them — often comes into conflict with other goals, such as the need for efficiency, privacy or security. There is no easy way to make those trade-offs disappear.

As for my email account, when I decided to write about my experience for this column, I emailed Google’s press office with the details to see if I could discuss the issue. By the end of the day, my access to my email account had been restored. I was pleased, of course, but I don’t think many people would see that as particularly fair either.

Hugh Ferguson

Hugh Ferguson made a very helpful short comment on Club Troppo. I looked him up on the net. I expect I’ve got another Hugh Ferguson, but there you go.

Lovely pics. You can follow him here.

DeepSeek v RentSeek

I have no idea how exemplary the Chinese are in the way claimed in the article below. I suspect it’s rather biased towards the idea of Chinese prowess as people were towards the Japanese in the late 1980s. Even so, consistent with the article’s argument, I suspect a fair bit of America's impressive economic performance relative to other developed economies stems from its success at rent extraction via its global tech and financial platforms.

DeepSeek works differently. [to other LLMs.] Its free, open-source model can be installed wholesale onto a (slightly specialised) personal computer. A “distilled” or simplified (that is, still as adept at reasoning if not as knowledgeable) version of DeepSeek’s model can then be used and edited offline, for no extra cost. This is a colossal development. It means that any Chinese user wishing to discuss Tiananmen Square would simply need to download DeepSeek onto an offline computer, without fear of a CCP hack, and edit the model. Voilà: you’ll have permanent access to a high-performance AI that will talk to you about any heretical subject you like. …

Like any community, an open-source community is ruled by hierarchies. A company at the leading edge of such a network is likely to attract collaborators, and gain trust and credit. Since DeepSeek published its models, it has been contacted by dozens of leading AI researchers and companies in the US and China. It will now be busy making powerful new friends, and discussing new techniques. If it can build quickly on its successes, DeepSeek will gain much from sharing its research. …

American tech leaders are still right to be alarmed. DeepSeek didn’t come out of nowhere, but has emerged from a vast ecosystem of Chinese tech talent. How many Westerners have heard of CATL, Hesai, DJI, SMIC, Oppo, Pony.ai, Zhiyuan? — among the world’s best companies in robotics, autonomous driving, drones, lidar, AI and battery technology. DeepSeek is really only the tip of the iceberg — one which the US is about to crash straight into. …

How did it all go wrong for the West? Steve Hsu, an American physicist, argues that China is eclipsing America when it comes to cultivating human capital in the sciences, maths and engineering. Within a couple of generations, malnutrition (which stunts brain development) has been all but eliminated in China; the majority of children now graduate from high school, and roughly 60% go on to university. Nearly a third of students study STEM subjects at university, compared to just 3% a generation ago. And China’s best universities are now ranked as highly as those in the West.

Due to the size of China’s population, these reforms have left the country with a much larger, and still growing, pool of very smart and highly STEM-educated citizens. … And the long era of Chinese brain drain is finally over: more and more, Chinese STEM graduates remain in or return to China rather than trying their luck in the West, their prospects at home bolstered by a dynamic economy and improved standards of living. In fact, the humiliating trend has begun to reverse, with the annual number of scientists leaving the US for China increasing by a factor of five or so in the last 15 years.

Critically, and unlike in the West, China’s STEM graduates gravitate towards jobs in engineering, design, technology, and basic research rather than in finance. DeepSeek itself illustrates the precarity of China’s finance industry — it grew out of a quantitative investment fund that was hit eight months ago by a government crackdown on computer-driven high-speed trading.

Might an aversion to finance be a blessing for China? Steve Hsu likes to quote what billionaire investor Charlie Munger said of America’s elite culture: “I regard the amount of brainpower going into money management as a national scandal. […] We have armies of people with advanced degrees in physics and math in various hedge funds and private-equity funds trying to outsmart the market. […] It’s crazy to have incentives that drive your most intelligent people into a very sophisticated gaming system.”

Competition and Survival in Modern Academia

I seem to remember someone associated with this newsletter thinks modern academia’s contribution to the accumulation of genuine high quality knowledge is collapsing — certainly in the social sciences. Oh right — that was me. So it’s no surprise I popped this into the mix.

Jesper Grimstrup and Jarl Sidelmann have an interesting new paper [using] bibliometric data to study career paths in hep-th [High energy physics — theory], especially how many people who start out in the field are still in it at various later times. …

The problem with this kind of thing though is that on the whole the people making decisions about what to do are the “survivors”, for whom the current system has worked out just fine. They’re the least likely people to think there’s a crisis or to see any reason to do anything about it. As for the job situation (which has been terrible since 1970), I can report that when one doesn’t have a permanent job this seems to be an important and serious problem, but once one does have a permanent job all of a sudden it seems much less important.

What has struck me most in recent decades about hep-th is not the bad job environment, but the monotone-decreasing number of interesting new ideas, now so small that I don’t think “intellectual collapse” is an unfair characterization of what’s happened. I started carefully following the latest preprints in the field more than 40 years ago, pre-arXiv, when they were collected physically at a “preprint library” in one’s institution. Most preprints in hep-th have always been minor advances, not of much interest unless you’re working on much the same problem, but in the past there were always a significant number with something really new and significant to report. The arrival in the preprint library of something new from Witten or any number of other well-known figures in the field was an event, and there also was a steady stream of new ideas coming from people not so well-known. In recent years the situation has been very different, with something worth reading appearing in the arXiv hep-th section less and less often, to the point where it’s a rare occurrence.

This slow death of the field I believe is a very real phenomenon, although I’m not sure how one could quantify it. There are multiple reasons for why it has happened, some of which are just facts of life (the SM is too good, no unexpected experimental results). I do think though that one reason is the one the authors here are trying to get at: decades and decades of a difficult job situation where the only viable way to win the game of survivor is to publish lots of papers in a dwindling number of accepted research programs. This is one problem that the field actually could do something about, but chances of that happening seem remote.

Heaviosity half-hour

As I think I mentioned last week, I’ve been enjoying Sarah Bakewell’s At the Existentialist Café. I sent a copy to a friend saying how much I was enjoying it. I got back this reply.

Sarah Bakewell’s book, the one you sent me, is fabulous! As you said, her writing is good. Well it’s more than merely good - it’s exemplary. It's not just that her sentences, paragraphs, etc are exquisitely formed, but that so much sheer content is packed in. She effortlessly compounds judgements with facts and impressions. Take the attached, which I've literally selected at random. The first three sentences are outstanding: "In Nausea, art brings liberation because it captures things as they are and gives them an inner necessity. They are no longer bulbous and nauseating: they make sense. Roquentin's jazz song is the model for this process.” What a miracle of objectivity and subjectivity these words are - they fuse facts, thoughts and impressions so carefully that the result feels found not made. If they could sit on the head of a pin - or more’s the point, right at the tip of the sharp end - then she would be about driving them through the paragraph to the very end.

That her field of resources is so deep is testament not only to her labour, but to the superiority of her mind. I don’t often find myself wondering about someone else’s raw intelligence - but I do in her case. I am so clearly out classed - all I can do is pull back in wonder. To read the book, if I can take it in, will, I suppose, do me good, and for a number of reasons. First, in the moral sense of putting me in my place; second, in encouraging me to make the most of what I have and learn how to do this well; and third, in teaching me things I didn’t know about this post war generation, and the angst they must have felt as they searched for a way to be without God but with a vivid memory of total war, occupation and execution and the threat of a fusion bomb, which is an atheism all in itself.

Thanks again Nick - you’ve given me something to sink my teeth into. Her bio is interesting.

Indeed it is. And fun. This is how it concludes.

I live mostly in London, and enjoy the usual glamorous writer’s life: putting a comma in, taking it out, putting it back in again, and eventually deleting the whole sentence.

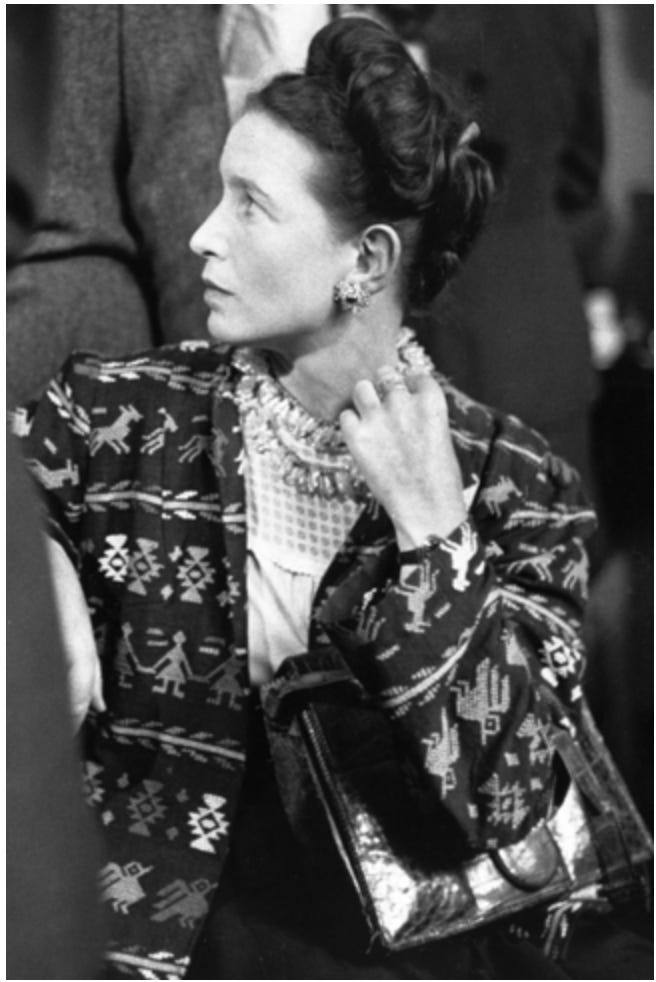

In any event, this week’s heaviosity half-hour is Bakewell’s chapter on Simone de Beauvoir.

Woman writes great book. Onlookers remain sceptical.

LIFE STUDIES

In which existentialism is applied to actual people.

One day, somewhere around the time of the 1948 Berlin trip, Beauvoir was sitting with pen in hand, staring at a sheet of paper. Alberto Giacometti said to her, ‘How wild you look!’ She replied, ‘It’s because I want to write and I don’t know what.’ With the sagacity that came from its being someone else’s problem, he said, ‘Write anything.’

She did, and it worked. She took further inspiration from her friend Michel Leiris’ experimental autobiographical writings, which she had recently read: these inspired her to try a free-form way of writing about her memories, basing them around the theme of what it had meant to her to grow up as a girl. When she discussed this idea with Sartre, he urged her to explore the question in more depth. Thus it is in relation to three men that Simone de Beauvoir describes the origin of her great feminist work, The Second Sex.

Perhaps the starting point had been a modest idea in need of masculine encouragement, but Beauvoir soon developed the project into something revolutionary in every sense: her book overturned accepted ideas about the nature of human existence, and encouraged its readers to overturn their own existences. It was also a confident experiment in what we might call ‘applied existentialism’. Beauvoir used philosophy to tackle two huge subjects: the history of humanity — which she reinterpreted as a history of patriarchy — and the history of an individual woman’s whole life as it plays itself out from birth to old age. The two stories are interdependent, but occupy two separate parts of the book. To flesh them out, Beauvoir combined elements of her own experience with stories gathered from other women she knew, and with extensive studies in history, sociology, biology and psychology.

She wrote quickly. Chapters and early versions appeared in Les Temps modernes through 1948; the full tome came out in 1949. It was greeted with shock. This freethinking lady existentialist was already considered a disturbing figure, with her open relationship, her childlessness and her godlessness. Now here was a book filled with descriptions of women’s sexual experience, including a chapter on lesbianism. Even her friends recoiled. One of the most conservative responses came from Albert Camus, who, as she wrote in her memoirs, ‘in a few morose sentences, accused me of making the French male look ridiculous’. But if men found it uncomfortable, women who read it often found themselves thinking about their lives in a new way. After it was translated into English in 1953 — three years before Being and Nothingness and nine years before Heidegger’s Being and Time — The Second Sex had an even greater impact in Britain and America than in France. It can be considered the single most influential work ever to come out of the existentialist movement.

Beauvoir’s guiding principle was that growing up female made a bigger difference to a person than most people realised, including women themselves. Some differences were obvious and practical. French women had only just gained the right to vote (with Liberation in 1944), and continued to lack many other basic rights; a married woman could not open her own bank account until 1965. But the legal differences reflected deeper existential ones. Women’s everyday experiences and their Being-in-the-world diverged from men’s so early in life that few thought of them as being developmental at all; people assumed the differences to be ‘natural’ expressions of femininity. For Beauvoir, instead, they were myths of femininity — a term she adapted from the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, and which ultimately derived from Friedrich Nietzsche’s ‘genealogical’ way of digging out fallacies about culture and morality. In Beauvoir’s usage, a myth is something like Husserl’s notion of the encrusted theories which accumulate on phenomena, and which need scraping off in order to get to the ‘things themselves’.

After a broad-brush historical overview of myth and reality in the first half of the book, Beauvoir devoted the second half to relating a typical woman’s life from infancy on, showing how — as she said — ‘One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.’

The first influences begin in early childhood, she wrote. While boys are told to be brave, a girl is expected to cry and be weak. Both sexes hear similar fairy tales, but in them the males are heroes, princes or warriors, while the females are locked up in towers, put to sleep, or chained to a rock to wait to be rescued. Hearing the stories, a girl notices that her own mother stays mostly in her home, like an imprisoned princess, while her father goes off to the outside world like a warrior going to war. She understands which way her own role will lie.

Growing older, the girl learns to behave modestly and decorously. Boys run, seize, climb, grasp, punch; they literally grab hold of the physical world and wrestle with it. Girls wear pretty dresses and dare not run in case they get dirty. Later, they wear high heels, corsets and skirts; they grow long fingernails which they have to worry about breaking. They learn, in countless small ways, to hesitate about damaging their delicate persons if they do anything at all. As Iris Marion Young later put it in ‘Throwing Like a Girl’, a 1980 essay applying Beauvoir’s analysis in more detail, girls come to think of themselves as ‘positioned in space’ rather than as defining or constituting the space around them by their movements.

Adolescence brings a more heightened self-consciousness, and this is the age in which some girls become prone to self-harming, while troubled boys are more likely to pick fights with others. Sexuality develops, but small boys are already aware of the penis as something important, while the girl’s genitals are never mentioned and seem not to exist. Early female sexual experiences may be embarrassing, painful or threatening; they may bring more self-doubt and anxiety. Then comes the fear of pregnancy. (This was written well before the Pill.) Even if young women enjoy sex, female sexual pleasure can be more overwhelming, and thus more disturbing, says Beauvoir. It is generally linked to marriage, for most women, and with this comes the repetitive and isolating labour of housework, which accomplishes nothing out in the world and is no real ‘action’.

By now, all these factors have conspired to hold a woman back from establishing authority and agency in the wider world. The world is not a ‘set of tools’ for her, in the Heideggerian sense. Instead it is ‘dominated by fate and run through with mysterious caprices’. This is why, Beauvoir believes, women rarely attain greatness in the arts or literature — although she makes an exception for Virginia Woolf, who showed, in her 1928 work A Room of One’s Own, what disasters were likely to befall an imaginary sister of Shakespeare’s born with the same talents. Beauvoir sees every element of women’s situation as conspiring to box them in to mediocrity, not because they are innately inferior, but because they learn to become inward-looking, passive, self-doubting and overeager to please. Beauvoir finds most female writers disappointing because they do not seize hold of the human condition; they do not take it up as their own. They find it difficult to feel responsible for the universe. How can a woman ever announce, as Sartre does in Being and Nothingness, ‘I carry the weight of the world by myself’?

For Beauvoir, the greatest inhibition for women comes from their acquired tendency to see themselves as ‘other’ rather than as a transcendent subject. Here she drew on her wartime reading of Hegel, who had analysed how rival consciousnesses wrestle for dominance, with one playing ‘master’ and the other ‘slave’. The master perceives everything from his own viewpoint, as is natural. But, bizarrely, so does the slave, who ties herself in knots trying to visualise the world from the master’s point of view — an ‘alienated’ perspective. She even adopts his point of view on herself, casting herself as object and him as subject. This tormented structure eventually collapses when the slave wakes up to the fact that she has it all backwards, and that the whole relationship rests on the hard work that she is doing — on her labour. She rebels, and in doing so she becomes fully conscious at last.

Beauvoir found the Hegelian vision of human relationships as a protracted battle of gazes or perspectives a richly productive idea. She had been talking it through with Sartre for years. He too had been interested in the master–slave dialectic since the 1930s, and had made it a major theme in Being and Nothingness. Since his examples illustrating the battle of alienated gazes are particularly lively, let us detour away from Beauvoir for a few moments to visit them.

In his first example, Sartre asks us to imagine walking in a park. If I’m alone, the park arranges itself comfortably around my point of view: everything I see presents itself to me. But then I notice a man crossing the lawn towards me. This causes a sudden cosmic shift. I become conscious that the man is also arranging his own universe around himself. As Sartre puts it, the green of the grass turns itself towards the other man as well as towards me, and some of my universe drains off in his direction. Some of me drains off too, for I am an object in his world as he is in mine. I am no longer a pure perceiving nothingness; I have a visible outside, which I know he can see.

Sartre then adds a twist. This time he puts us in the hallway of a Parisian hotel, peering through the keyhole of someone’s door — perhaps because of jealousy, lust or curiosity. I am absorbed in whatever I’m seeing, and strain towards it. Then I hear footsteps in the hall — someone is coming! The whole set-up changes. Instead of being lost in the scene inside the room, I am now aware of myself as a peeping tom, which is how I’ll appear to the third party coming down the hall. My look, as I peer through the keyhole, becomes ‘a look-looked-at’. My ‘transcendence’ — my ability to pour out of myself towards what I am perceiving — is itself ‘transcended’ by the transcendence of another. That Other has the power to stamp me as a certain kind of object, ascribing definite characteristics to me rather than leaving me to be free. I fight to fend this off by controlling how that person will see me — so, for example, I might make an elaborate pretence of having stooped merely to tie my shoelace, so that he does not brand me a nasty voyeur.

Episodes of competitive gazing recur throughout Sartre’s fiction and biographies, as well as in his philosophy. In his journalism, he recalled the unpleasantness after 1940 of feeling oneself looked at as a member of a defeated people. In 1944, he wrote a whole play about it: Huis clos, translated as No Exit. It depicts three people trapped together in a room: a military deserter accused of cowardice, a cruel lesbian, and a flirtatious gold-digger. Each looks judgementally at at least one of the others, and each longs to escape their companions’ pitiless eyes. But they cannot do so, for they are dead and in hell. As the play’s much-quoted and frequently misunderstood final line has it: ‘Hell is other people.’ Sartre later explained that he did not mean to say that other people were hellish in general. He meant that after death we become frozen in their view, unable any longer to fend off their interpretation. In life, we can still do something to manage the impression we make; in death, this freedom goes and we are left entombed in other’s people’s memories and perceptions.

Sartre’s vision of living human relationships as a kind of intersubjective ju-jitsu led him to produce some very strange descriptions of sex. Judging by the discussion of sexuality in Being and Nothingness, a Sartrean love affair was an epic struggle over perspectives, and thus over freedom. If I love you, I don’t want to control your thoughts directly, but I want you to love and desire me and to freely give up your freedom to me. Moreover, I want you to see me, not as a contingent and flawed person like any other, but as a ‘necessary’ being in your world. That is, you are not to coolly assess my flaws and irritating habits, but to welcome every detail of me as though no jot or tittle could possibly be different. Recalling Nausea, one might say that I want to be like the ragtime song for you. Sartre did realise that such a state of affairs is unlikely to last long. It also comes with a trade-off: you are going to want the same unconditional adoration from me. As Iris Murdoch memorably put it, Sartre turns love into a ‘battle between two hypnotists in a closed room’.

Sartre derived this analysis of love and other encounters at least in part from what Simone de Beauvoir had made out of Hegel. They both pored over the implications of the master–slave dialectic; Sartre worked out his striking and bizarre examples, while Beauvoir made it the more substantial basis of her magnum opus. Her reading was more complex than his. For a start, she pointed out that the idea of love, or any other relationship, as a reciprocal encounter between two equal participants had missed one crucial fact: real human relationships contained differences of status and role. Sartre had neglected the different existential situations of men and women; in The Second Sex, she used Hegel’s concept of alienation to correct this.

As she pointed out, woman is indeed ‘other’ for man — but man is not exactly ‘other’ for woman, or not in the same way. Both sexes tend to agree in taking the male as the defining case and the centre of all perspectives. Even language reinforces this, with ‘man’ and ‘he’ being the default terms in French as in English. Women try constantly to picture themselves as they would look to a male gaze. Instead of looking out to the world as it presents itself to them (like the person peering through the keyhole) they maintain a point of view in which they are the objects (like the same person after becoming aware of footsteps in the hall). This, for Beauvoir, is why women spend so much time in front of mirrors. It is also why both men and women implicitly take women to be the more sensual, the more eroticised, the more sexual sex. In theory, for a heterosexual female, men should be the sexy ones, disporting themselves for the benefit of her gaze. Yet she sees herself as the object of attraction, and the man as the person in whose eyes she glows with desirability.

Women, in other words, live much of their lives in what Sartre would have called bad faith, pretending to be objects. They do what the waiter does when he glides around playing the role of waiter; they identify with their ‘immanent’ image rather than with their ‘transcendent’ consciousness as a free for-itself. The waiter does it when he’s at work; women do it all day and to a greater extent. It is exhausting, because, all the time, a woman’s subjectivity is trying to do what comes naturally to subjectivity, which is to assert itself as the centre of the universe. A struggle rages inside every woman, and because of this Beauvoir considered the problem of how to be a woman the existentialist problem par excellence.

Beauvoir’s initial fragments of memoir had by now grown into a study of alienation on an epic scale: a phenomenological investigation not only of female experience but of childhood, embodiment, competence, action, freedom, responsibility and Being-in-the-world. The Second Sex draws on years of reading and thinking, as well as on conversations with Sartre, and is by no means the mere adjunct to Sartrean philosophy that it was once taken to be. True, she successfully shocked one feminist interviewer in 1972 by insisting that her main influence in writing it was Being and Nothingness. But seven years later, in another interview, she was adamant that Sartre had nothing to do with working out Hegelian ideas of the Other and the alienated gaze: ‘It was I who thought about that! It was absolutely not Sartre!’

Whatever had fed it, Beauvoir’s book outdid Sartre’s in its subtle sense of the balance between freedom and constraint in a person’s life. She showed how choices, influences and habits can accumulate over a lifetime to create a structure that becomes hard to break out of. Sartre also thought that our actions often formed a shape over the long term, creating what he called the ‘fundamental project’ of a person’s existence. But Beauvoir emphasised the connection between this and our wider situations as gendered, historical beings. She gave full weight to the difficulty of breaking out of such situations — although she never doubted that we remain existentially free despite it all. Women can change their lives, which is why it is worth writing books to awaken them to this fact.

The Second Sex could have become established in the canon as one of the great cultural re-evaluations of modern times, a book to set alongside the works of Charles Darwin (who resituated humans in relation to other animals), Karl Marx (who resituated high culture in relation to economics) and Sigmund Freud (who resituated the conscious mind in relation to the unconscious). Beauvoir evaluated human lives afresh by showing that we are profoundly gendered beings: she resituated men in relation to women. Like the other books, The Second Sex exposed myths. Like the others, its argument was controversial and open to criticism in its specifics — as inevitably happens when one makes major claims. Yet it was never elevated into the pantheon.

Is this further proof of sexism? Or is it because her existentialist terminology gets in the way? English-speaking readers never even saw most of the latter. It was cut by its first translator in 1953, the zoology professor Howard M. Parshley, largely on the urging of his publisher. Only later, reading the work, did his editor ask him to go easy with the scissors, saying, ‘I am now quite persuaded that this is one of the handful of greatest books on sex ever written.’ It was not just omissions that were the problem; Parshley rendered Beauvoir’s pour-soi (for-itself) as ‘her true nature in itself’, which precisely reverses the existentialist meaning. He turned the title of the second part, ‘L’expérience vécue’ (‘lived experience’), into ‘Woman’s Life Today’ — which, as Toril Moi has observed, makes it sound like the title of a ladies’ magazine. To make matters more confusing and further demean the book, English-language paperback editions through the 1960s and 1970s tended to feature misty-focus naked women on the cover, making it look like a work of soft porn. Her novels got similar treatment. Strangely, this never happened with Sartre’s books. No edition of Being and Nothingness ever featured a muscleman on the cover wearing only a waiter’s apron. Nor did Sartre’s translator Hazel Barnes simplify his terminology — although she notes in her memoirs that at least one reviewer thought she should have.

If sexism and the existentialist language were not to blame, another reason for The Second Sex’s intellectual sidelining might be that it presents itself as a case study: an existentialist study of just one particular type of life. In philosophy, as in many other fields, applied studies tend to be dismissed as postscripts to more serious works.

But that was never existentialism’s way. It was always meant to be about real, individual lives. If done correctly, all existentialism is applied existentialism.

Retrospectoscope and Robodebt and Public Service reviews/reports all put me in mind of Don Watson's scathing critiques of language: Weasel Words; Bendable Learnings; and Death Sentences!

The exchange of e-mails of Cameron Murray and Paul Frijters reminds me that it was their 2017 book Game of Mates which I came across a couple of years later which explained to me much of why Australia seemed to have become a tasteless kind of political and economic mess during my nearly two decades through the 1990s and 2000s in Japan. Your added comments on how the NDIS became the mess it seemingly is now made a lot of sense - and in the meantime the unscrupulous have grown fat off the misfortunes of those least able to manage their situations... I enjoyed part watching the Cher documentary; the DeepSeek AI situation vis-à-vis the US tech-giant oligarchs and the essay on Simone de Beauvoir... Thanks.

"something is more ‘scientific’ if it’s more mathematical."

Similar thing bot logic and analytical philosophy as they call it nowadays, but really, in a game metaphor, it is just a type of minecrafting the technology tree,

the more continental deconstruction of course, like suicide chess, does it in reverse

both are textmachines, which LLMs will glad ghost for you without a spirit of reason in charge