International councils of citizens: can they moderate the madness?

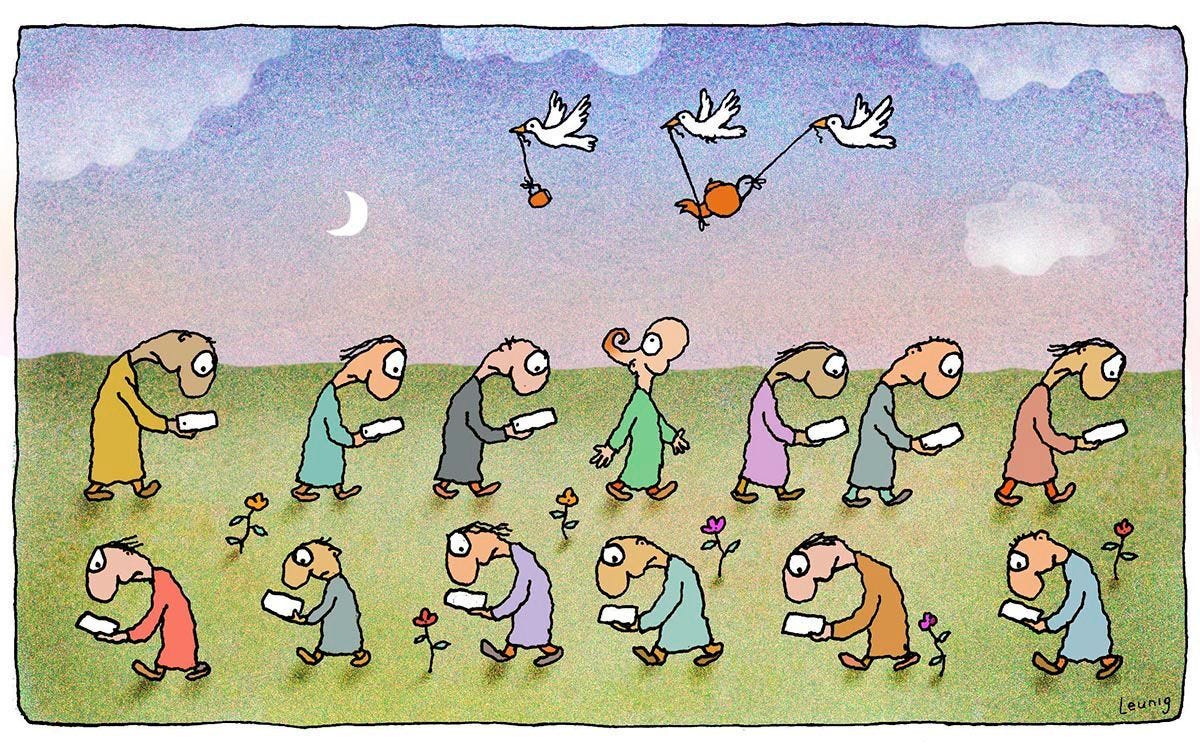

As readers may know, in contrast to most folks promoting citizen assemblies, I am not too optimistic that running temporary, special purpose citizen assemblies will achieve much. They come and go, serve up some recommendations to the government and then become ‘issues management’ fodder, and in so doing rehearse the role of the people as supplicants to their government. I think we need to develop an activism of sortition. By that I mean we need to find ways to assert the legitimacy of the deliberation of a representative sample of the people as a check and balance on the government. Had a citizen assembly voted against the abolition of carbon pricing in Australia or against a hard Brexit in the UK, it would have markedly strengthened the hand of those elected politicians who were resisting bad policy within the legislature.

Given the case for an activism of sortition, it seemed to me that Donald Trump’s trade war on the world offered a promising environment in which to improvise. I discuss this idea with Leon Gettler in the recording above. If you want to check it out on your podcast app, you should be able to listen here.

Suicide in fin de siècle Vienna

Ian Leslie, a journalist of some terrificness has published an essay which is … well … terrific. Here’s the version of it that Claude produced when asked to cut it down as best it could to 700 words to give you the sense of it, but I recommend clicking through. I did!

On the morning of January 30, 1889, Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria and his mistress Mary Vetsera were found dead in the prince's bedroom at the Imperial Hunting Lodge at Mayerling, in the woods outside Vienna. Rudolf was 30, Mary was 17. Rudolf had shot Mary in the head, before turning the gun on himself. Lovers for just a short while, the two had made a suicide pact. Mary left letters of farewell to her family: "Please forgive me for what I've done. I could not resist love…I am happier in death than life."

The news rocked Europe, where Rudolf was famous and admired. He was seen as more modern, dynamic and far-seeing than his rather stiff father, the Habsburg ruler, Franz Joseph, emperor of Austria and king of Hungary. Rudolf's early death made a tear in the fabric of history. Since Rudolf had no son, the new heir presumptive became Franz Joseph's nephew, Franz Ferdinand. Franz Joseph was still emperor on 28 June, 1914, when that plan bit the dust too.

I've been reading Frederic Morton's 1979 book, A Nervous Splendour, which sets the Mayerling incident in the context of fin-de-siècle Vienna. Certain cities, during certain periods, exert disproportionate influence on world culture: Paris in the 1920s; New York in the 1970s; Dubai in the 2020s (joke. I think). Vienna around the turn of the century might just outdo them all.

In that city, at that time, psychology was reinvented by Freud, classical music by, in turn, Mahler and Schoenberg; visual arts by Klimt and Schiele; architecture by Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos; economics by von Mises; literature by Schnitzler and Zweig; Jewish identity by Herzl. Hayek (economics), Popper, and Wittgenstein (both philosophy) were Viennese too, even if they did their revolutionary work elsewhere...

Morton focuses on a short period at the beginning of this phase: the turn of 1888 into 1889. Apart from Rudolf and Vetsera, his cast of characters includes the 32-year-old Sigmund Freud, established, barely, as a neurologist, and just starting to grope towards the ideas that became psychoanalysis...

All of them are in some way frustrated and anxious, which was typical: Vienna was, famously, a nervous city. It was full of hysterics, of both sexes (it took Freud to point out that the condition was not specific to women), intense over-thinkers, overstrung status-seekers, apocalyptic doomers. Its feverish creativity emerged from claustrophobic diversity: in coffee houses enclosed by the Ringstrasse - the grand boulevard encircling Vienna's inner city - chemists and psychiatrists and composers mingled with novelists and artists and physicists, caffeine fuelling their edgy conversations.

This was a city of extreme, bipolar pleasures. The Viennese were fuelled by cocaine, champagne, sex and dancing; stupefied by morphine, pastries, cakes and cigars. Culturally, there was an emphasis on ephemerality, on taking hits of hedonism while being cynically aware of the meaninglessness of it all. Many young people, overwhelmed by a feeling of futility, contemplated the ultimate revolt against this existence; suicide rates were high, particularly among the upper classes...

Suicide was aestheticised and competitive. A tightrope walker hung himself from a rope tied to the window handle of his tenement. He left a note: "The rope was my life and the rope is my death." An elegant young woman aboard the express train to Budapest entered the toilet with her suitcase, changed into a bridal gown, opened the car door, leaped out. She was found dead by the rails, white lace stained with blood...

The crown prince's staff noticed how closely he read press accounts of these grisly events. In company, Rudolf was affable and charming, but privately he brooded. The son and heir of a relatively young emperor, he was all prestige and no purpose, a condition familiar to Kendall Roy and Prince Harry. Politically speaking, he was a liberal who wanted to modernise the monarchy and the country, but found his efforts in that direction smothered by Franz Josef and deadening tradition. On turning thirty, he wrote to a friend, "We live in a slow, rotten time…this eternal living-in-preparation, this permanent waiting for great times of reform, weakens one's best powers…"

Morton, a Viennese Jew whose family emigrated to America in 1940 (his life story is amazing) had a compelling theory of why fin-de-siècle Vienna had this anxious, almost manic-depressive temperament...

Come the late nineteenth century, Vienna was still run by soldiers and courtiers. The Crown dispensed political power to a small, intensely competitive population of aristocrats. Vienna's intellectually inclined inhabitants had the sense of living in a city of brittle illusions, increasingly detached from the rest of rapidly industrialising Europe. Without the energy and common sense of a commercial class, Vienna felt like a gold-leafed yacht drifting aimlessly out to sea as storm clouds gathered on the horizon. Some passengers chose to throw themselves overboard.

Nice, crisp unpaywalled piece from Henry Oliver

Felix Martin: Will the stock market keep sinking?

There's no shortage of theories around to explain the stalling of the U.S. stock market this year... Yet the biggest threat to the four-decade-long run in American equities lies in the United States's superannuating population. Three decades ago, the infamous "market meltdown hypothesis" predicted disaster once the baby-boom generation hit retirement age. That fear didn't play out straight away, but the idea may be about to have its day.

The alarmingly named theory postulated that the age structure of the U.S. population might constitute a timebomb for the stock market. Rising to prominence in the 1990s, it rested on a simple observation. The so-called baby-boom cohort, born between 1946 and 1964, is much larger than those before and after it – a pig passing through the body of a python, as one memorable metaphor put it.

Economists warned that this demographic lump set the stage for a drama in two acts. In the first, the stock market would boom, as the postwar generation entered its prime earning years and ploughed its growing retirement savings into equities. In the second, however, the process would swing into reverse. The boomers would attempt to fund their sunset years by offloading their nest eggs onto a much smaller Generation X...

"The words 'Sell? Sell to whom?' might haunt the baby boomers in the next century", wrote investment guru Jeremy Siegel in the 1998 edition of his classic "Stocks for the Long Run". "Who are the buyers of the trillions of dollars of boomer assets?"

The 1980s and 90s seemed to corroborate the first part of the story... By 2000, the cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio of U.S. stocks had climbed from a low of under 7 in 1982 to over 44.

In the 2000s, however, the disastrous denouement failed to materialise... The globalisation of financial markets meant that instead of struggling to offload shares onto the piddling Generation X, U.S. boomers were greeted by a global savings glut desperate to invest in American companies... The meltdown hypothesis was thus forgotten.

Yet the dynamics that worried the demographic doomsters of the 1990s remain alarmingly intact. Perhaps the retirement-age selloff was just deferred. Last year, even the youngest baby boomers turned 60, while the oldest are fast approaching their ninth decade. U.S. private pension funds have indeed turned from net buyers of financial assets to net sellers... The boomers' mass drawdown of their savings has begun.

Meanwhile, the generation of U.S. savers available to absorb the boomers' selling is as puny as predicted. According to World Bank data, there were 5.5 working-age Americans for every over-65 in 1990. By 2023 that number had fallen below 4. It was based on just such a collapse in the ratio of demand and supply that the market meltdown hypothesis Cassandras warned that stocks could easily drop by a third when the boomers sold.

That might turn out to be an underestimate. Since the 1990s, two new demographic factors have emerged which threaten to make a U.S. market meltdown even more painful than its original prophets predicted.

The first relates to the inflows of international capital that helped bail out the early retiring boomers... Europe, Japan and China were the biggest buyers by far. In all of them, the fall in the ratio of the working-age to the retired has been as steep as, or even steeper than, the equivalent shift in the United States. In other words, just as U.S. boomers are accelerating their selling, the foreign buyers who have been picking up the slack are now facing [similar demographic pressures].

The second new demographic factor may be more important still. The anomalous size of the American postwar generation conferred not just economic but domestic political clout too... Shortly after 2015, however, that dominance came to an end. Voters born after 1981, namely millennials and Generation Z, usurped the boomers...

It would be facile to ascribe the successive political earthquakes that have rocked the U.S. since 2016 to that demographic shift alone... Yet it is surely no coincidence that it was just as the boomers' electoral ascendancy was finally eclipsed that the political settlement in favour of globalisation went into precipitous decline. The generation of millennial Vice President JD Vance just doesn't have the same vested interest in the policies that staved off the boomers' initial date with destiny.

"Bull markets don't die of old age", the market adage goes. On this occasion, however, the market adage may be wrong.

Employment, satisfaction, productivity and enlightened self-interest

Economists love trade-offs. And there certainly are trade-offs in economics, though economists instinct that everything always gets down to trade-offs is, as I’ve argued, fairy-floss metaphysics. For me that means I’m always on the lookout for ways in which people’s self-interest and others’ interest coincide if only we have the wit to find it. In any event one of the guiding ideas behind the kind of economics my father practiced was the idea that a lot of good can be gained for the world by people understanding the difference between their self-interest and their enlightened self-interest. Thus for instance, after you have enough money, you get more satisfaction from helping others than you do piling it up for yourself.

Likewise there are lots of benefits for firms that try to profit from the coincidence of wellbeing of both customers and employees. I came upon the paper linked to below, and didn’t want to wade through the whole thing, so got Claude to summarise it.

Can Finding Your Purpose at Work Pay Off? New Research Shows Promise and Pitfalls

A groundbreaking study of nearly 3,000 workers reveals that helping employees discover their personal purpose can boost performance and profits—but only under specific conditions.

The Treatment: "Discover Your Purpose"

The intervention, tested at a multinational consumer goods company, takes a radically different approach from typical corporate training. Instead of imposing company values on workers, it helps employees identify their own life purpose through a structured process:

Pre-work (2 weeks): Employees read materials including Viktor Frankl's "Man's Search for Meaning" and prepare four personal stories about formative life experiences

Workshop (8 hours): Small groups share their stories and identify common themes to craft a personal "purpose statement"

Application: Workers then assess whether their current job aligns with their discovered purpose

The key insight: rather than pushing workers to exert costly effort, the intervention helps them find meaning in their work—or realize they should find work elsewhere.

The Results: Selection and Performance

The randomized experiment produced striking outcomes:

Worker Movement: Exit rates increased by 21% as employees with low job-meaning left for better-aligned opportunities. Critically, this wasn't random turnover—it was purposeful sorting.

Performance Gains: The share of low performers dropped by 25%. Half came from poor performers leaving; half from remaining workers improving their effort. Bonus payments increased significantly among those who stayed.

Well-being Benefits: Participants reported higher job satisfaction, life happiness, and meaning at work. Gender gaps in workplace priorities narrowed, with men becoming 52% more likely to take parental leave.

Cultural Shifts: The intervention helped workers prioritize personal values over social expectations, creating more authentic workplace behavior.

The Economics: When Does It Pay?

The financial case hinges on two critical factors: how long effects persist and how many workers respond.

Base Case Costs: $1,119 per participant, including lost work time, coordination costs, and higher turnover expenses.

Annual Benefits: $1,161 per worker in improved productivity and reduced replacement costs—but only while effects last.

[Insert table graphic showing Effect Duration vs Returns]

Break-even point: Effects must persist approximately 13 months to justify costs.

Sensitivity to Key Assumptions

The intervention's success depends heavily on worker responsiveness:

High-Response Scenario (similar to study results):

21% exit rate increase among mismatched workers

25% reduction in low performers

Strong business case if effects last 2+ years

Low-Response Scenario (workers less willing to leave/change):

5% exit rate increase

10% reduction in low performers

Requires 3+ years of persistence to break even

External Implementation: Using outside consultants instead of internal facilitators increases costs to $1,837 per worker, requiring longer effect persistence but still profitable if benefits last 2+ years.

The Adoption Puzzle

Despite potentially high returns, such interventions remain rare. The study reveals why: observational data misleads managers. When companies pilot purpose programs without randomization, high performers self-select to participate while struggling workers avoid them. This makes it appear the intervention doesn't help low performers—masking its true value.

The randomized trial showed the opposite: the intervention primarily benefits struggling workers through either performance improvement or better job matching.

Implications and Caveats

This research suggests a new model for workplace motivation: instead of incentivizing costly effort, help workers find inherent meaning in their tasks. But success requires:

Cultural readiness: Organizations must genuinely support workers who choose to leave for better-aligned opportunities

Persistent effects: Benefits must last well beyond the first year

Worker responsiveness: Employees must be willing to act on insights about job-purpose alignment

The intervention works by turning the traditional principal-agent model "upside down"—putting worker purpose at the center rather than company objectives. When successful, it creates shared value: workers become both more productive AND happier.

However, the thin margins between success and failure highlight why rigorous experimentation, rather than intuition, should guide such investments in human capital.

Election won, Albo lets his hair down

With deep fakes taking off, I was afraid this was a deep fake, but it wasn’t. And so Eric Schliesser’s speculations from 2023 seem vindicated.

For generations now Israel has pursued a policy of divide and rule against the Palestinians, while (to use an euphemism) discouraging the development of popular, local democratic leaders in occupied territories. It has also failed to incorporate Israeli-Arab participation in coalition governments as a routine matter. Three significant (related) effects of this have been that, first, no Palestinian partner could ever deliver on any agreement and, second, radical factions always had an effective veto over any Israeli-Palestinian rapprochement. And, third, Zionism has come to be understood by its enemies and itself as a project that cannot allow Palestinian agency.

These effects have been visible since (and arguably caused) the collapse of the Oslo process from the very beginning. Since Israel has been too happy to assume it could, instead, pursue a process of normalization with Arab dictators who need American weapons and/or money (or both), all the while expanding ‘facts on the ground’ in the West Bank while leaving systematically ambiguous what its end-game is. Within Israel this has emboldened maximalists who pretend Palestinians away in word and deed, and it has created abject conditions in the Gaza strip and despair in the West Bank.

Unlike most Zionists, I view such ambiguity especially as a long-term strategic disaster, despite the undeniable tactical advantages it generates in the apparent short-term. For, contemporary Zionism (as represented by the State of Israel) has five structural and longstanding weaknesses: i) the failure to establish permanent borders for the state of Israel; (ii) the inability to settle what kind of political entity Israel should be so that it can end its near-permanent war-footing and settler occupation of hostile populations; (iii) (the perception of) Israel's dependence on America's political and military support, which ties Israel to America's strategic interests and electoral politics, while (iv) allowing a split between the interests of Zionism and American Jewry to develop; (v) Israel’s failure to provide Palestinians with positive incentives and symbolic declarations to come to peace with Israel. (Many of these are interrelated, of course.)

Bernard Keane on the opportunity of dumb

For a country notionally obsessed with how to lift productivity and growth, Australia seems oddly uninterested in the easiest way of all to improve both: import them. Donald Trump's systematic destruction of the US economy and its global appeal is presenting enormous opportunities for policymakers to exploit Australia's growing comparative attraction compared to the United States.

While tariffs, policy uncertainty, blatant corruption and reputational damage have all been scrutinised as significant parts of the damage inflicted by Trump and the MAGA cult on the United States, migration has received less attention. That's because policymakers and the broader governing class, including the media, have bought into one of the core elements of the MAGA worldview, that migration is fundamentally problematic and must be regulated as a threat. But that makes about as much sense as the neoliberal view that free movement of people is always and everywhere a good, and should be regulated as little as possible.

In that context, other core elements of neoliberalism — the enfeeblement of government and its role in infrastructure and service provision, and the distortion of policymaking by powerful economic forces — have served to undermine support for high migration. Governments were encouraged to outsource and sell off infrastructure, and slash investment and the taxes needed to fund it, leaving communities to bear the brunt of increasing population size without commensurate growth in infrastructure and services...

Instead of addressing those structural problems, it was a lot easier simply to blame migration — whether you're a MAGA Republican engaging in the racial NIMBYism of exploiting white resentment, or an Australian education minister trying to reduce foreign student numbers on the spurious basis that they take our houses.

But no proponent of lower migration is ever able to answer a fairly basic question: where are the workers we need for a modern economy going to come from? And as the 2020s become the 2030s and western societies and China go from ageing to shrinking populations, the question is going to become more acute. The poor productivity growth of Australia and other Western economies also requires we ask where the highly skilled and innovative workers are going to come from.

Adopting an implacable hostility to migration, or an openly racist migration policy as the United States now has — no refugees are welcome unless they are white — is a simple refusal to engage with reality, unless you prefer lower economic growth, higher inflation, not being able to find anywhere to look after your aged parents or your toddler, and waiting three months to get a tradie.

Conveniently for Australia, Donald Trump is extending his hatred of migration to one of the most economically beneficial forms: foreign students. His regime has already made the United States — ostensibly the most attractive place in the world to study — markedly less attractive to foreign students through visa cancellations, kidnapping students off the street, and his economic war with China...

The potential benefits for Australia are significant. While Australia can't replicate the research opportunities of US institutions or the appeal of working in the world's largest economy, we're an Anglophone country with strong educational standards and greater proximity to key markets such as China and India. More, and more high-quality, foreign students should be encouraged to come to Australia rather than risk studying in Trump's increasingly fascist dystopia.

The same principle applies to attracting academic talent. Unlike the United States, Australia can commit that it doesn't randomly turn back academics at the border, that the rule of law applies here and that, despite the toxic, if declining, influence of News Corp, there remains a degree of academic freedom in our institutions.

Indeed, all Australian industries that seek to attract international talent should be reflecting on how to use Trump's immolation of American appeal to our benefit. Given our health sector remains the industry with the direst skill shortages, we should be looking to cherrypick talent from the US health sector, with the pitch that unlike the United States under Trump, in Australia we actually believe in science and have a commitment to a public health sector and health research, and seek to remunerate care sector workers fairly. The same applies across other skilled or professional categories, around half of which face shortages...

From the point of view of the 2050s, when the world's population may already be shrinking, [today's anti-migration mindset is] going to look staggeringly wrongheaded.

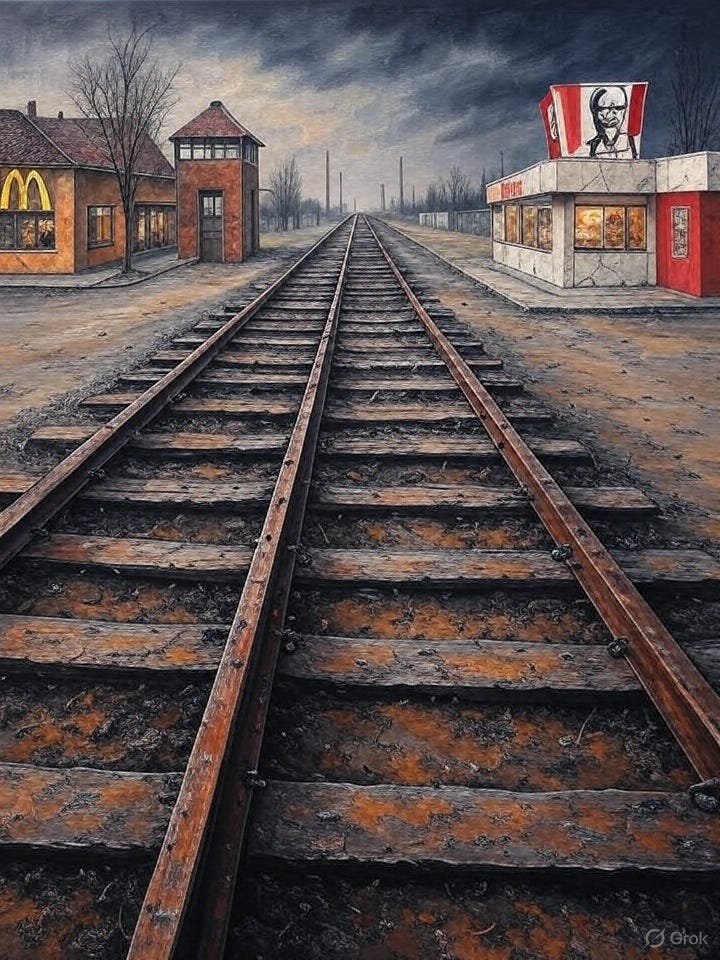

Is history rhyming?

Is this just like the 1930s? Well yes and no. Obviously. But this column does draw our attention to an important point. And it’s inline with my hunch that much more of our current woes are a product of ‘cultural’ causes than material ones. That cultural cause is that our politics is not fit for human habitation. It is so staged, so artificial, so manipulative, so performative with all these things being so optimised that people want to tear it all down.

From Janan Ganesh in the FT.

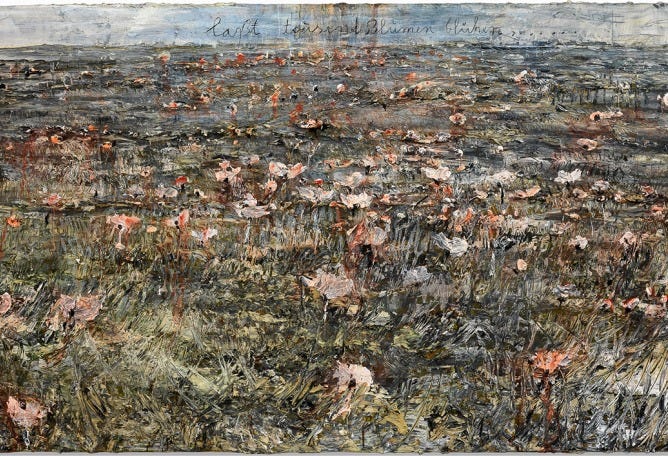

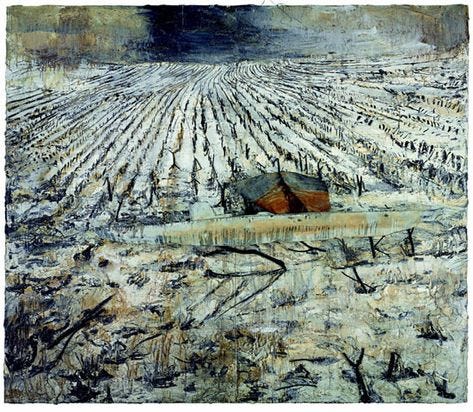

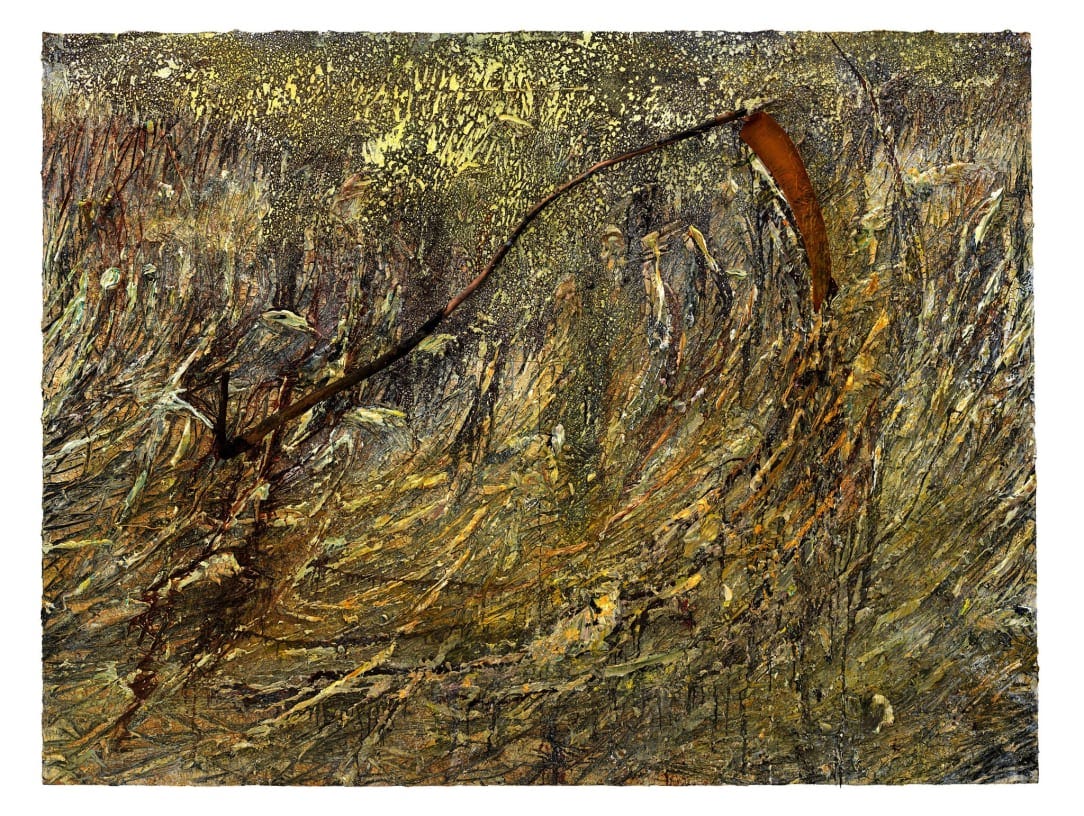

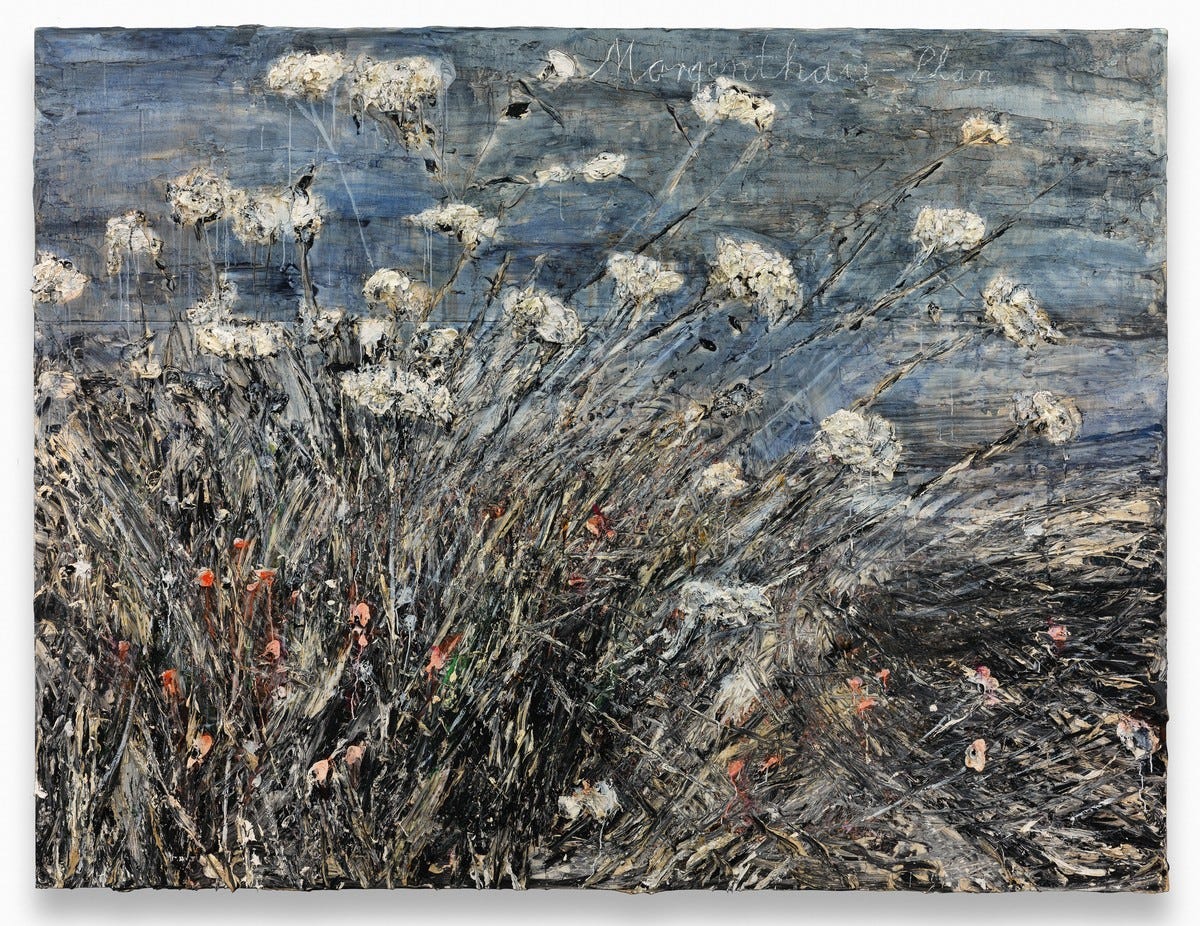

Those who regard Anselm Kiefer as the greatest living artist will see enough proof in his Amsterdam show. Those who find his work journalistic, too full of moralising comment about real events, won't change their minds either. The title of the exhibition comes from an anti-war song, after all. There are burnt-out uniforms and the Nazi references that he has used for much of his career. "We have a situation now like in 1933 in Germany," he has said, alluding to contemporary populism.

Do we? Eighty years have passed since the end of the second world war (and Kiefer's birth). He is far from alone in using the moment to warn about that past repeating itself. This trope never goes away. If only it would.

The 1930s are an almost useless guide to what is happening now. The strongmen back then came out of an era of scarcely precedented chaos: the great war, hyperinflation, political gangs fighting for control of the streets. Today's demagogues emerged in a period of sustained peace and affluence. It was more or less the richest nation on Earth that elected Donald Trump in 2016, after decades of falling violent crime, and more than 40 years since its last conscript war. The Britain that voted to leave the European project had far more industrial peace and international standing than the one that first joined. As for Germany, the far right's voting base maps almost perfectly on to the old East, which is unrecognisably richer and freer than it was at reunification...

These aren't just different stories, then, but almost opposing ones. The lesson of the 1930s is that people who suffer — economic pain, physical fear, national territorial loss — are liable to turn to extremists. The lesson of today is that not suffering can induce them to do the same thing. After too long a period of calm, boredom sets in. The temptation to take risks with one's vote starts to grow. Stability destabilises. The 1930s is simple to understand, as it conforms to common sense: trauma leads to anger. The real intellectual challenge is to absorb the theme of our own time, which is the perverse consequences of prolonged success.

Where does this idea come from, anyway, that people forget the war? Books about it and its origins help to sustain the popular non-fiction market. Films on the subject never stop coming. It is the one historical reference in everyone's locker. Churchiliana is a transatlantic industry...

It is the contrasts that stand out between then and now, not the echoes. In all its variations — German, Italian, Japanese — 1930s despotism put a huge emphasis on military sacrifice. Trump doesn't even seem to like being around veterans. Interwar fascists had a corresponding distaste for commerce as something effete. Trump shills for Tesla cars and digital funny money. The likes of Mussolini wanted to pervade almost all areas of life. Trump is autocratic but not totalitarian, which isn't just a difference of degree.

"When will we ever learn?" is something of a slogan for Kiefer. In 2016, had a leader come along in epaulettes, twirling a moustache, riding a tank, we would have seen through them in no time, precisely because we have learnt. It is the very novelty of today's demagogues that makes them so hard to spot and beat. For all the talk of remembering, we might have to forget the last disaster to avert the next one.

Anselm Kiefer

Poem by Robert Hayden

I ran into this on American Scholar.

American poet and essayist Robert Hayden was born in Detroit in 1913 and died in 1980. He had a difficult childhood and was raised primarily in foster care, where he became an avid reader. Hayden went on to study under W. H. Auden, earn a master’s degree, produce several poetry collections, and become the first Black poet to serve as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (a position now known as Poet Laureate). This week’s Read Me a Poem selection was suggested by one of our listeners, who writes, “As a father who sacrificed a lot for my two grown sons while struggling with chronic loneliness, shame and despair … [I was reduced] to tears when I first read it.”

Listen to it here:

Those Winter Sundays

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.I’d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he’d call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices?

AI accelerates intellectual collapse: SHOCK!

An institution that produced this …

Can certainly produce this

Abstract

This paper describes a process for automatically generating academic finance papers using large language models (LLMs). It demonstrates the process' efficacy by producing hundreds of complete papers on stock return predictability, a topic particularly well-suited for our illustration. We first mine over 30,000 potential stock return predictor signals from accounting data, and apply the Novy-Marx and Velikov (2024) "Assaying Anomalies" protocol to generate standardized "template reports" for 96 signals that pass the protocol's rigorous criteria. Each report details a signal's performance predicting stock returns using a wide array of tests and benchmarks it to more than 200 other known anomalies. Finally, we use state-of-the-art LLMs to generate three distinct complete versions of academic papers for each signal. The different versions include creative names for the signals, contain custom introductions providing different theoretical justifications for the observed predictability patterns, and incorporate citations to existing (and, on occasion, imagined) literature supporting their respective claims. This experiment illustrates AI's potential for enhancing financial research efficiency, but also serves as a cautionary tale, illustrating how it can be abused to industrialize HARKing (Hypothesizing After Results are Known).

Heaviosity half-hour: Memorial edition

Alasdair MacIntyre, RIP

I can only answer the question, ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question, ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’

Alasdair MacIntyre

I’m occasionally asked to name books that have been transformative for me. As I responded to someone recently “It’s tricky, I read a lot of articles and books and they have their influence on me, but I can’t say there are many that have somehow changed the way I think in some transformative way”. The two who have done so did not produce any conversion experience, but gave me things to ponder to which I returned again and again.

Doing history in the late 1970s and early 1980s I became a devotee of the ‘Cambridge school of the history of political thought’. This school rejected the anachronistic interpretation or reading of past thinkers through modern conceptual lenses (what Skinner called the danger of “mythology of doctrines”). And that took me back to the Oxford philosopher R. G. Collingwood. (I tried to outline a contemporary practical application of his thought here.

The other person I’d name as shaping my own thinking is the Aristotelian/Thomist philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre who died last week on the 21st of May. I remember browsing in the ANU book coop when his most famous book After Virtue hit the stands in 1981. I remember reading its bracing opening - which I’ve replicated below. It sketches a future society after some catastrophic event like “a series of environmental disasters” are blamed on science. In the upshot, mobs destroy laboratories and join pogroms against scientists. Eventually, a more reflective mood emerges, and science is revived, but only in fragments. People use scientific terms like “neutrino” or “momentum,” but they no longer understand their underlying concepts.

I recall thinking at the time, this was a perfect description of how the various artefacts of neoclassical economics related to economic reality. No-one really worries too much how the ideas map onto reality. They map onto each other and you can build models and ‘fit’ them to the data you have. Today, I’d say most academic social science is like that.

Anyway, the analogy MacIntyre intended was more fundamental. He was arguing that the ethical understanding of our post-Enlightenment world is a jumble of artefacts which don’t hang together and yet people press on asserting one argument against another as if they did hang together. This is the ethical world of ‘emotivism’.

In case you want to do any more reading around, here’s a recent reflection on his career in moral philosophy previously extracted in Heaviosity half-hour. Here’s the Guardian obit. Here’s another one. And here’s a good piece, which includes MacIntyre’s claim to breaking up the Beatles.

Anyway, over to the late Alasdair MacIntyre.

A Disquieting Suggestion

Imagine that the natural sciences were to suffer the effects of a catastrophe. A series of environmental disasters are blamed by the general public on the scientists. Widespread riots occur, laboratories are burnt down, physicists are lynched, books and instruments are destroyed. Finally a Know-Nothing political movement takes power and successfully abolishes science teaching in schools and universities, imprisoning and executing the remaining scientists. Later still there is a reaction against this destructive movement and enlightened people seek to revive science, although they have largely forgotten what it was. But all that they possess are fragments: a knowledge of experiments detached from any knowledge of the theoretical context which gave them significance; parts of theories unrelated either to the other bits and pieces of theory which they possess or to experiment; instruments whose use has been forgotten; half-chapters from books, single pages from articles, not always fully legible because torn and charred. Nonetheless all these fragments are reembodied in a set of practices which go under the revived names of physics, chemistry and biology. Adults argue with each other about the respective merits of relativity theory, evolutionary theory and phlogiston theory, although they possess only a very partial knowledge of each. Children learn by heart the surviving portions of the periodic table and recite as incantations some of the theorems of Euclid. Nobody, or almost nobody, realizes that what they are doing is not natural science in any proper sense at all. For everything that they do and say conforms to certain canons of consistency and coherence and those contexts which would be needed to make sense of what they are doing have been lost, perhaps irretrievably.

In such a culture men would use expressions such as ‘neutrino’, ‘mass’, ‘specific gravity’, ‘atomic weight’ in systematic and often interrelated ways which would resemble in lesser or greater degrees the ways in which such expressions had been used in earlier times before scientific knowledge had been so largely lost. But many of the beliefs presupposed by the use of these expressions would have been lost and there would appear to be an element of arbitrariness and even of choice in their application which would appear very surprising to us. What would appear to be rival and competing premises for which no further argument could be given would abound. Subjectivist theories of science would appear and would be criticized by those who held that the notion of truth embodied in what they took to be science was incompatible with subjectivism.

This imaginary possible world is very like one that some science fiction writers have constructed. We may describe it as a world in which the language of natural science, or parts of it at least, continues to be used but is in a grave state of disorder. We may notice that if in this imaginary world analytical philosophy were to flourish, it would never reveal the fact of this disorder. For the techniques of analytical philosophy are essentially descriptive and descriptive of the language of the present at that. The analytical philosopher would be able to elucidate the conceptual structures of what was taken to be scientific thinking and discourse in the imaginary world in precisely the way that he elucidates the conceptual structures of natural science as it is.

Nor again would phenomenology or existentialism be able to discern anything wrong. All the structures of intentionality would be what they are now. The task of supplying an epistemological basis for these false simulacra of natural science would not differ in phenomenological terms from the task as it is presently envisaged. A Husserl or a Merleau-Ponty would be as deceived as a Strawson or a Quine.

What is the point of constructing this imaginary world inhabited by fictitious pseudo-scientists and real, genuine philosophy? The hypothesis which I wish to advance is that in the actual world which we inhabit the language of morality is in the same state of grave disorder as the language of natural science in the imaginary world which I described. What we possess, if this view is true, are the fragments of a conceptual scheme, parts which now lack those contexts from which their significance derived. We possess indeed simulacra of morality, we continue to use many of the key expressions. But we have—very largely, if not entirely—lost our comprehension, both theoretical and practical, or morality.

But how could this be so? The impulse to reject the whole suggestion out of hand will certainly be very strong. Our capacity to use moral language, to be guided by moral reasoning, to define our transactions with others in moral terms is so central to our view of ourselves that even to envisage the possibility of our radical incapacity in these respects is to ask for a shift in our view of what we are and do which is going to be difficult to achieve. But we do already know two things about the hypothesis which are initially important for us if we are to achieve such a shift in viewpoint. One is that philosophical analysis will not help us. In the real world the dominant philosophies of the present, analytical or phenomenological, will be as powerless to detect the disorders of moral thought and practice as they were impotent before the disorders of science in the imaginary world. Yet the powerlessness of this kind of philosophy does not leave us quite resourceless. For a prerequisite for understanding the present disordered state of the imaginary world was to understand its history, a history that had to be written in three distinct stages. The first stage was that in which the natural sciences flourished, the second that in which they suffered catastrophe and the third that in which they were restored but in damaged and disordered form. Notice that this history, being one of decline and fall, is informed by standards. It is not an evaluatively neutral chronicle. The form of the narrative, the division into stages, presuppose standards of achievement and failure, of order and disorder. It is what Hegel called philosophical history and what Collingwood took all successful historical writing to be. So that if we are to look for resources to investigate the hypothesis about morality which I have suggested, however bizarre and improbable it may appear to you now, we shall have to ask whether we can find in the type of philosophy and history propounded by writers such as Hegel and Collingwood—very different from each other as they are, of course—resources which we cannot find in analytical or phenomenological philosophy.

But this suggestion immediately brings to mind a crucial difficulty for my hypothesis. For one objection to the view of the imaginary world which I constructed, let alone to my view of the real world, is that the inhabitants of the imaginary world reached a point where they no longer realized the nature of the catastrophe which they had suffered. Yet surely an event of such striking world historical dimensions could not have been lost from view, so that it was both erased from memory and unrecoverable from historical records? And surely what holds of the fictitious world holds even more strongly of our own real world? If a catastrophe sufficient to throw the language and practice of morality into grave disorder had occurred, surely we should all know about it. It would indeed be one of the central facts of our history. Yet our history lies open to view, so it will be said, and no record of any such catastrophe survives. So my hypothesis must simply be abandoned. To this I must at the very least concede that it will have to be expanded, yet unfortunately at the outset expanded in such a way as to render it, if possible, initially even less credible than before. For the catastrophe will have to have been of such a kind that it was not and has not been—except perhaps by a very few—recognized as a catastrophe. We shall have to look not for a few brief striking events whose character is incontestably clear, but for a much longer, more complex and less easily identified process and probably one which by its very nature is open to rival interpretation. Yet the initial implausibility of this part of the hypothesis may perhaps be slightly lessened by another suggestion.

History by now in our culture means academic history, and academic history is less than two centuries old. Suppose it were the case that the catastrophe of which my hypothesis speaks had occurred before, or largely before, the founding of academic history, so that the moral and other evaluative presuppositions of academic history derived from the forms of the disorder which it brought about. Suppose, that is, that the standpoint of academic history is such that from its value-neutral viewpoint moral disorder must remain largely invisible. All that the historian—and what is true of the historian is characteristically true also of the social scientist—will be allowed to perceive by the canons and categories of his discipline will be one morality succeeding another: seventeenth-century Puritanism, eighteenth-century hedonism, the Victorian work-ethic and so on, but the very language of order and disorder will not be available to him. If this were to be so, it would at least explain why what I take to be the real world and its fate has remained unrecognized by the academic curriculum. For the forms of the academic curriculum would turn out to be among the symptoms of the disaster whose occurrence the curriculum does not acknowledge. Most academic history and sociology—the history of a Namier or a Hofstadter and the sociology of a Merton or a Lipset—are after all as far away from the historical standpoint of Hegel and Collingwood as most academic philosophy is from their philosophical perspective.

It may seem to many readers that as I have elaborated my initial hypothesis I have step by step deprived myself of very nearly all possible argumentative allies. But is not just this required by the hypothesis itself? For if the hypothesis is true, it will necessarily appear implausible, since one way of stating part of the hypothesis is precisely to assert that we are in a condition which almost nobody recognizes and which perhaps nobody at all can recognize fully. If my hypothesis appeared initially plausible, it would certainly be false. And at least if even to entertain this hypothesis puts me into an antagonistic stance, it is a very different antagonistic stance from that of, for example, modern radicalism. For the modern radical is as confident in the moral expression of his stances and consequently in the assertive uses of the rhetoric of morality as any conservative has ever been. Whatever else he denounces in our culture he is certain that it still possesses the moral resources which he requires in order to denounce it. Everything else may be, in his eyes, in disorder; but the language of morality is in order, just as it is. That he too may be being betrayed by the very language he uses is not a thought available to him. It is the aim of this book to make that thought available to radicals, liberals and conservatives alike. I cannot however expect to make it palatable; for if it is true, we are all already in a state so disastrous that there are no large remedies for it.

Do not however suppose that the conclusion to be drawn will turn out to be one of despair. Angst is an intermittently fashionable emotion and the misreading of some existentialist texts has turned despair itself into a kind of psychological nostrum. But if we are indeed in as bad a state as I take us to be, pessimism too will turn out to be one more cultural luxury that we shall have to dispense with in order to survive in these hard times.

I cannot of course deny, indeed my thesis entails, that the language and the appearances of morality persist even though the integral substance of morality has to a large degree been fragmented and then in part destroyed. Because of this there is no inconsistency in my speaking, as I shall shortly do, of contemporary moral attitudes and arguments. I merely pay to the present the courtesy of using its own vocabulary to speak of it.