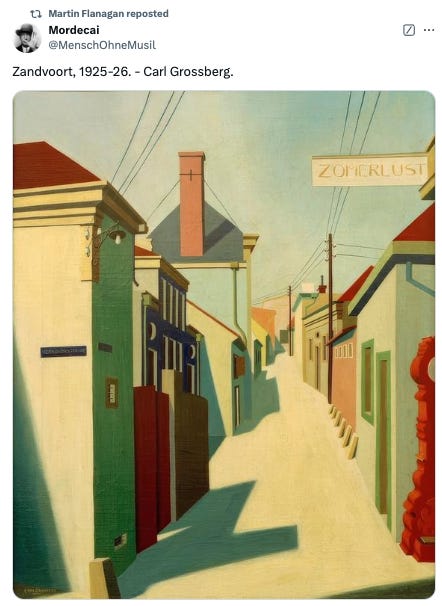

What the 20th century might have been like

I remember when I first saw this view, I said to my son “Matey, this is what the 20th century could have been like — a grand reimagining of its whole inheritance.” I was struck that this was ‘modernism’ at the turn of the 20th century — that it took several more decades to degrade into brutalism. (Just as the modernism in economics took several more decades to degrade into the neurotic sterility of neoclassical economics. In policy it took only about half a decade for the useful deregulation of early neoliberal reform — cutting trade barriers and other bits of detritus like the economic regulation of civil aviation — to the sterility of late neoliberal agendas such privately funded monopoly assets like toll-roads and transmission lines.)

Frank Lloyd' Wright’s modernism was very different to Gaudi’s, but similar in its fertility, it’s respect for craft, its attention to the beauty of surfaces and its attempts to construct spaces and stages for something new and beautiful to emerge. Both were also fascinated by geometry, though Gaudi’s interest is more transformative in Sagrada Familia.

Anyway, the prompt for this outburst is the existence of a doco on SBS on Gaudi’s creation, complete with an interview with Mark Burry who chose to study Gaudi in his post graduate work in the 1970s when Gaudi was deeply disapproved of within the academy. Burry helped find ways to realise Gaudi’s vision despite Gaudi’s failure to leave detailed drawings behind. Burry lives in Melbourne and has done for decades, but he commuted to Barcelona about five times a year for many years as Executive Architect and one of the people bringing Gaudi’s vision to life.

Anyway, Orwell described Sagrada Familia as “the most hideous building in the world'' and thought the Anarchists showed bad taste in not blowing the whole thing up on the one occasion when they had the chance during the Civil War. He had a point of course. I’ve always wondered if I just got carried away on that day when I walked into the building. People are allowed to have different views on it, but I loved this confession by a doubter turned convert. (This was roughly my reaction. I liked Gaudi’s other buildings, but only for their eccentricity and exuberance, not because I thought them masterpieces. That was one reason why walking into Sagrada Familia had such an impact on me.)

As a university student in Barcelona in the early 1960s, Catalan architect Oscar Tusquets Blanca was one of the leaders of a campaign opposing any further construction work on Antoni Gaudí's unfinished Sagrada Familia church. Now, 50 years later, after taking a guided tour of the Sagrada Familia in the company of one of the building's project architects, he has publicly recanted. Writing in the March 2011 edition of the Italian architecture magazine Domus, Tusquets Blanca says some of the building's finishes and decorative features — handrailings, stained glass and flooring — are not on a par with the whole, and the sculptures on the Passion façade done by Josep Maria Subirachs are "pitiful." But overall he says, his tour of the Sagrada Familia left him "dumbfounded."

"How could we have been so wrong? This wonder would not exist if people had listened to us 50 years ago…. I do not know whether [the Sagrada Familia] is the finest work of the last century but it will certainly be the greatest religious building of the last three." …

Mark Burry says Gaudí's style developed through three distinct stages during his career: an early "historicist" or Gothic Revival phase known in Catalan as the Renaixença; a much more free-form middle phase associated with Art Nouveau that included many of his best-known projects, including the Park Güell, the Casa Batlló and the Casa Milà; and a late phase, dating from around 1912 and roughly corresponding with when he was working exclusively on the Sagrada Familia, when Gaudí adopted a more rationalist, classical style, using ruled or quadratic geometry and working with shapes such as paraboloids, hyperboloids and conoids.

The Sagrada Familia was originally commissioned by a private foundation of conservative Catholics, the Associació Espiritual de Devots de Sant Josep (Spiritual Association of Devotees of St Joseph), and Gaudí was not the first architect to work on the project. Between 1883, when he took on the commission, and his death in 1926, his ideas for the Sagrada Familia continually evolved. The Nativity façade of the Sagrada Familia belongs to these first and second phases. Professor Mark Burry says he suspects it started out in Gothic Revival style and that Gaudí then deliberately subverted it with great festoons of leaves and flowers, to "absolve its insistence" and "send the message that the Gothic only gets you halfway there."

It's pretty worrying, to be honest, that these guys are able to write with such power and such ignorance.

The late phase previously existed only in Gaudí's smashed plaster models, and it has been revealed only now to the wider public in the Sagrada Familia's interior.

We now can see that art critic Robert Hughes got Gaudí completely wrong in The Shock of the New (1980), when he wrote that "To the classicist's eye," buildings like the Sagrada Familia are "outright madness: not a straight line anywhere. To advanced modernist taste in the 1920s — Bauhaus taste, in a word — Art Nouveau was sickeningly gratuitous." The quadratic or ruled surface geometry that produced the paraboloids, hyperboloids and conoids of the Sagrada Familia, is nothing but straight lines.

I ask Mark Burry how he feels looking back at Robert Hughes's 1992 attack on the efforts of the project to complete the Sagrada Familia. "It is extraordinary," says Burry, "that [Hughes] felt able to savage a half-finished art work. It's pretty worrying, to be honest, that these guys are able to write with such power and such ignorance."

ANU’s University House: High modernism at its best

A slightly tarted up email exchange with a friend on the plans to rescue University House from storm damage. (With apologies for repeating the analogy between modernism and neoliberalism above.)

From me:

Completed when my father was beginning his productive life at 31, having returned from his studies in the US, ANU’s University House is an architectural embodiment of all he stood for. Comfortable and generous but far from luxurious with even a nod to austerity. Conducive to thoughtful calm. A refectory with a fine mural — if not quite up to Leonardo's standards ;) A large space for civilised shared living — the library — where people might meet casually, and everyone was trusted to care for the books and newspapers a state that everyone contributes to as they enjoy. Modestly beautiful, modernist (a bit like early neoliberalism — worthwhile and vibrant in its early stages then turned to brutalist junk by becoming a fashion and a costume one could put on to do a little marauding with one's mates.)

From my friend — who lived for a while in University House:

Thanks for this Nick - it was lovely to read. I liked the way you combined it with the neoliberal idea as it was in its heyday. As you say modern - but in a very generous 1950s way. … Part of the success of it was that each week day had the same quiet work-focussed rhythm Wednesday dinners in the Great Hall were celebration of progress. The emphasis was on doing the job and producing content - but always modestly, as you say. It was very civilised, without being the least meretricious.

From an email shortly afterwards:

It’s entirely lacks the egotism that almost always comes with the way Chopin is played. I didn’t know egotism was lacking at University House, until I discovered it growing everywhere else.

Frank Lloyd Wright furniture for you to live with

Brian Eno mulls marauding modernism

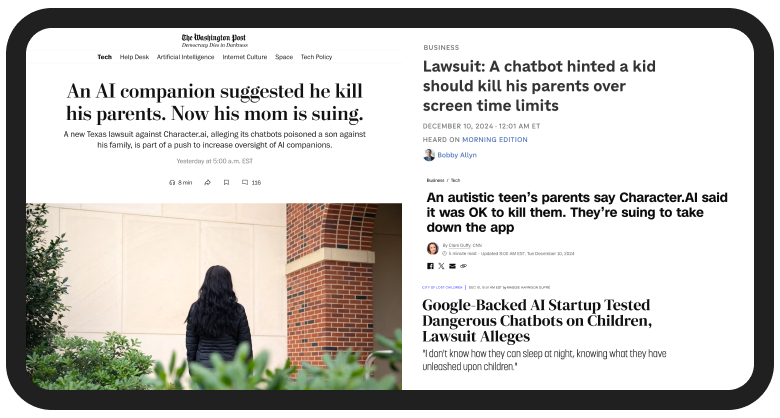

Brian Eno thinks about AI. He’s not too impressed, as he’s probably not too impressed with this AI portrait of him.

Thoreau’s adage “beware of all enterprises that require new clothes” should perhaps be updated to “beware of all enterprises that require venture capital.”

Morozov argues that AI itself has much to offer, but it has not lived up to its potential to serve the public good, and the context of AI’s development explains why. I agree. My own misgivings about AI have less to do with the technology itself than with the problematic nature of who owns it, and what they want to do with it. Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen’s wildly hubristic visions of the future are par for the course in West Coast technology in that they downplay even the possibility of any downsides, brusquely dismissing these as “safety-ism.” I for one wish there had been a few more “safety-ists” around when the algorithms for social media were being crafted. …

The magic of play is seeing the commonplace transforming into the meaningful.

AI today inverts the value of the creative process. The magic of play is seeing the commonplace transforming into the meaningful. For that transformation to take place we need to be aware of the provenance of the commonplace. We need to sense the humble beginnings before we can be awed by what they turn into—the greatest achievement of creative imagination is the self-discovery that begins in the ordinary and can connect us to the other, and to others.

Yet AI is part of the wave of technologies that are making it easier for people to live their lives in complete independence from each other, and even from their own inner lives and self-interest. The issue of provenance is critically important in the creative process, but not for AI today. Where something came from, and how and why it came into existence, are major parts of our feelings about it. We feel differently about a piece of music played by an orchestra in a concert hall than we do about exactly the same piece of music made by a kid in a bedroom with a good sample bank. The backstory matters! The event matters! The intentions matter! We have no idea of the actual origin of the text AI delivers to us. Does it matter that what we’ve scraped off the ether to feed our AIs is not by any means the whole of the world’s knowledge, but just the part that happened to have been published in printed books by the small sliver of the English-speaking world that happened to publish them—and made them available to AI bots? What kind of sausage is that? Surely Weisswurst, made of available scraps on the butcher’s floor.

AI is always stunning at first encounter: one is amazed that something nonhuman can make something that seems so similar to what humans make. But it’s a little like Samuel Johnson’s comment about a dog walking on its hind legs: we are impressed not by the quality of the walking but by the fact it can walk that way at all. After a short time it rapidly goes from awesome to funny to slightly ridiculous—and then to grotesque. Does it not also matter that the walking dog has no intentionality—doesn’t “know” what it’s doing?

In my own experience as an artist, experimenting with AI has mixed results. I’ve used several “songwriting” AIs and similar “picture-making” AIs. I’m intrigued and bored at the same time: I find it quickly becomes quite tedious. I have a sort of inner dissatisfaction when I play with it, a little like the feeling I get from eating a lot of confectionery when I’m hungry. I suspect this is because the joy of art isn’t only the pleasure of an end result but also the experience of going through the process of having made it. When you go out for a walk it isn’t just (or even primarily) for the pleasure of reaching a destination, but for the process of doing the walking. For me, using AI all too often feels like I’m engaging in a socially useless process, in which I learn almost nothing and then pass on my non-learning to others. It’s like getting the postcard instead of the holiday. Of course, it is possible that people find beauty and value in the Weisswurst, but that says more about the power of the human imagination than the cleverness of AI.

AI: no more Mr Nice Guy

Speaking of our inheritance: The resurrection of Notre Dame

I doubt I would have read this whole article, but I came across it via Alan Jacobs’ newsletter highlighting part of the passage below. Then I listened to the author introducing and reading his piece as I was going to sleep. I loved the simplicity and modesty of his voice and what he was saying — so I saved it and reproduce the mp3 below even if you don’t have a NYT subscription (which you can get for the first year for AUD $20 which is pretty good). You can also download it for yourself here. :

I made it to the roof, where workers were securing the rebuilt spire and new rafters. Jean-Louis Bidet, the technical director of Ateliers Perrault, one of the French companies in charge of the carpenters, told me that each oak tree had been selected to match the contours of the ancient beam it would replace.

The tree was then carved to duplicate the peculiarities of the hand-tooled silhouette of the original, with the medieval carpenter’s mark even tattooed back onto it.

“Faithful” only began to describe the effort, which was not for show. The public won’t get to see the rafters that are now behind the restored ceiling vaults. I spoke with workers who came and went in the pop-up container village behind the apse, which had become headquarters for the restoration and where some of the 2,000 laborers, mostly French but some from elsewhere, picnicked under the trees during lunch.

“Each day we have 20 difficulties,” Philippe Jost, who headed the restoration task force, told me. “But it’s different when you work on a building that has a soul. Beauty makes everything easier.”

I can’t recall ever visiting a building site that seemed calmer, despite the pressure to finish on time, or one filled with quite the same quiet air of joy and certitude. When I quizzed one worker about what the job meant to her, she struggled to find words, then started to weep.

Michael Leunig RIP

I was a cartoonist for a few years. Srsly. And I went on a world tour selling trying to sell my cartoons. And of course I was pretty interested in the cartoons elsewhere. And though I’m biased, I’d say that that about five of the ten best cartoonists in the world were Australians. Michael Leunig was always the most singular, the most laugh out loud funny and quirky and soulful cartoonist we had. He will be sadly missed.

Some kindergarten tips on learning: Very enjoyable

In education, so much of effective pedagogy is making the abstract concrete for students. We do demonstrations in science class, we use graphs and visualizations in math, we do reenactments and role plays in language and history classes. The power of artifacts is why examples are such effective learning tools. Paul cites the work of Ron Berger and his emphasis on models of excellence. If you watch his “Austin’s Butterfly” video, you can see the impact a good example has on a young person’s understanding of “excellence.”

From an excellent substack post by educator Eric Hudson on how AI should and should not be used in schools. Tip: if effective use of one’s brain involves connecting it to all the other artefacts available — the body, the environment and others’ brains — then that should be at the heart of education.

Catholicism muscles into Jordan and Ben’s space

I think I’m safe from converting, but if you’re thinking of following Jordan or Ben (Shapiro), follow Robert instead. (But maybe just keep listening to Joe Rogan who doesn’t suffer from the self-absorbtion and intense humourlessness of the other two.)

From a big profile in the Atlantic.

Christian, but his fascination with the biblical narrative—not to mention his taste for menswear emblazoned with Orthodox icons—compels secular listeners to take a closer look at Christianity. Algorithms then guide them to Barron.) Geist realized that he had “been fed this milquetoast version of Christianity, not the deep, rich version that’s actually there.” His spiritual journey took some surprising turns, but Barron played a major role. Geist entered the Catholic Church in 2020.

Joining a religious community, submitting to its rules, and learning its traditions is hard. I could find no data to indicate how often Barron inspires listeners to put down their phones and start going to church. Progressive critics are skeptical that he’s much better than podcast bros like Joe Rogan at guiding young men toward “ethical heroism” and Christian virtue. After the actor Shia LaBeouf—once a self-described “Sam Harris, TED Talk, Christopher Hitchens guy”—began investigating Catholicism, Barron invited him onto his show. The liberal Catholic press criticized Barron for failing to confront LaBeouf about past run-ins with the law and accusations that he abused former girlfriends. (Those who watch the interview might see it differently. Although LaBeouf has said that “many of these allegations are not true,” he readily confessed to Barron that his egotism had inflicted “pain and damage on other people.”)

Another great Reith Lecture

Keeping things sweet with senior officials

One of my least favourite things is seeing politicians do bad things out of cowardice, when if their cowardice was just a little more hard headed, they'd do the right thing. As with Robodebt, so with whistleblowing. Actually dealing with some of this stuff might have made it a bit more easy for Albanese.

Lee Kuan Yew tells us what he really thinks of the Americans

Louise Perry on porn and female agency

Like lots of things I present here, I’m not up on this debate, but find it of considerable interest. A report from the front. The paywall cuts in just as she’d set the scene. But I wasn’t tempted.

As I argued in the book [the Case Against the Sexual Revolution], I don’t believe that women were the agents of the sexual revolution. Norms and laws changed rapidly because of the material changes brought about by new technology, particularly the Pill. If feminist campaigners made any difference, it was by hurrying the process along a bit (sorry, I don’t believe in ‘the great woman theory of history’). The result is a contemporary sexual culture that best serves the interests of a subset of high status men. But those men didn’t design the culture. There was never any conspiracy. This is just what happens when you take innate differences between the sexes and add dechristianisation, the internet, and the Pill. A perfect storm, I guess. Or an imperfect one.

I realise that this analysis doesn’t leave much space for agency, female or otherwise. Which is annoying for people who want to cast women as the main characters in this history, either as heroes or as villains. I understand why so many feminists are desperate to represent women as highly agentic – they’re trying to challenge the very sticky cross-cultural belief that women are childlike in a way that men aren’t. I’m not sure why so many anti-feminists are determined to do the same thing. Perhaps it’s because they’re so hyper-focused on women as the gatekeepers of sex that they assume women possess a similar gatekeeping power across all other domains.

But the truth is that very few people are highly agentic. I suspect that this is one of those personality traits that can be roughly represented as a bell curve, with just a few people at the far-right tail who are really capable of thinking independently, exhibiting self-control, actively changing their environment in pursuit of a higher goal, and generally exerting power over their own lives. Most people aren’t like that – this is what the insult ‘NPC’ is alluding to – and I don’t think that’s a bad thing. The normal way to behave is to do what other people do, aspire to what other people aspire to, and take a passive “it is what it is” attitude towards the culture at large. And that’s fine. After all, a society full of Type A nonconformists would be nightmarish. A bit of conformism is good, actually, as long as people are conforming to a functional model.

But what if the model isn’t functional? That’s the predicament that the 23-year-old OnlyFans star Lily Phillips finds herself in. A new documentary, I Slept With 100 Men in One Day, follows Phillips in the weeks leading up to an event in which she… well… “sleeps” isn’t really the right term. Phillips is, in her own words, “ran through by 100 guys” – random men recruited from her OnlyFans subscribers, invited to an AirBnB in London, and offered five minutes each. The event lasted fourteen hours. At the end, the cameraman entered the sex room and was so appalled by the smell that he audibly retched.

A clip of Phillips breaking down in tears after the 101st man has been making the rounds online and a popular opinion on Twitter is that she’s an evil whore. She chose this, the haters say, and she’ll keep choosing it – Phillips is planning to do the same thing in February, but this time with 1000 men. Her critics think she just loves money and attention. Her fans think she’s a businesswoman taking on an ambitious challenge. I think she’s sprinting for a cliff edge.

Turning up is 90% of life (but sometimes the other 10% matters more!)

I was expecting Bryan Robertson to arrive from Australia today. He had cabled from Perth a couple of weeks ago asking if he might stay a few days here. I'd cabled back immediately I'd be delighted. However I had a few private reservations about people who are so busy and self-important they have no time to write even when they're planning to save themselves the expense of a hotel. Bryan-I haven't seen him since meeting him in Ceylon-is very clever and amusing. He is a typical English culture-parasite of the kind that travels, wines, dines first class and free: and is welcome everywhere. Without creative talent, he manages to levy contributions from all and sundry. As an entrepreneur he arranges quite marvellous exhibitions of paintings from which people come away thinking, not of the fine paintings, but of how brilliant Bryan was to arrange it.

Diary entry of Donald Friend, Bali, 25 May, 1977

Then again Donald Friend was no angel. Strange for his publisher — the National Library — not to protect the names of the children he exploited.

Big tech and the Royal Society

Empathy: one of those teflon words, but not all good!

Worthwhile thread

Leaving me with the sense of disappointment that the only place to go if you’re fed up with the bossy sterility of the left is … the right :(

Impact investing

Meanwhile, if you want to save the world, what could be better than this luxury resort powered entirely by renewable energy, and funded by Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund? No wonder the petrostates are so keen on hosting the UNFCCC conferences of the parties. You may be as pleased as me to hear that the sovereign wealth fund’s designs its projects “to achieve cascading benefits for Saudi Arabia and the world”.

Ned tries some impact

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Hustling From Home?

Work from home flexibility lowers entrepreneurial entry

Abstract:We investigate the influence of the growing trend of work-from-home (WFH) on new business formation, with a particular focus on the period surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. At baseline, local new business entry is positively associated with the proportion of occupations amenable to telework in the region. Utilizing the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic and the implementation of stay-at-home mandates as an exogenous shock, we examine the effects of realized flexibility for WFH on entrepreneurial entry. While overall new business registrations increased following pandemic stay-at-home mandates, areas with an occupational mix that has higher potential for telework demonstrate less pronounced growth in new business formation, particularly in regions with lower economic demand factors. Survey evidence highlights how flexibility provided by traditional employment reduces entrepreneurial intent, especially for workers seeking non-pecuniary benefits such as autonomy or flexibility. Consistent with this substitution effect, we observe significant gender disparities, with a notable decline in women-led startups in areas with greater telework potential. Our results suggest a nuanced tension between the attractiveness of flexibility in traditional employment and the autonomy provided by entrepreneurial entry.

Henry Farrell on the management singularity

In a major post which he’s been mulling for a year Henry Farrell argues that AI may not replace humangoes any time soon, but it will transform large organisations by providing them with a whole new technology for synthesising the vast knowledge resources they contain, or must access from outside.

Back in February, I talked about some of the political economy problems of AI (or: more precisely, Large Language Models or LLMs), expressing other people’s skepticism about AI as true human-replacing super-intelligence. And in the interim we’ve seen some news suggesting that the case that men, women and human beings are soon going to be automated out of existence by strong AI is weaker than its advocates suggest.

But the case for the transformation of management is stronger, and AI skeptics should take it much more seriously.

Many lefties argue that LLMs are fundamentally useless - they don’t do anything that is conceivably valuable. But at the same time they worry that these technologies will become ubiquitous, fundamentally reshaping the economy around themselves. There isn’t any absolute logical contradiction between the two claims, and occasionally, quite stupid technologies have spread widely. Still, it’s unlikely that LLMs will become truly ubiquitous if they are truly useless. … My broader bet is that LLMs, like other big cultural technologies, will turn out to have (a) lots of socially beneficial uses, (b) costs and problems associated with these uses, and (c) some uses that aren’t plausibly socially beneficial at all.

Many of these uses will involve management. LLMs are engines for summarizing and making useful vast amounts of information. This is also the most difficult challenge facing large organizations such as government and big business. These organizations will deploy LLMs in ways that seem dull and technical, except to those immediately implicated for better or worse, but that are actually important. Big organizations shape our lives! As they change, so will our lives change, in a myriad of unexciting seeming but significant ways. Instead of the flare and dazzle of the usual Singularity stories - Vingean visions of vast pan-human galactic civilizations or sinister proliferating automated menaces - we are going to get More and Different Management. If LLMs are radically transformative, it will be in the apparently boring ways that the filing cabinet, and the spreadsheet were transformative, providing new tools for accessing and manipulating the kinds of complex knowledge and solving the big coordination problems that are the bread-and-butter of big organizations.

The Crisis that Germany Needs?

Barry Eichengreen explains Germany’s predicament.

In the aftermath of World War II – a period of upheaval and crisis but also of renovation and opportunity – what was then West Germany developed a set of economic and political institutions ideally suited to the conditions of the time. …

The happy result of this alignment of institutions and opportunities was the Wirtschaftswunder, the growth miracle of the third quarter of the twentieth century, when West Germany outperformed its major advanced-economy rivals (with the sole exception of Japan).

Unfortunately, these same institutions and arrangements proved exceedingly difficult to modify when circumstances changed. Focusing on quality manufacturing became problematic with the rise of new competitors, including China, yet German firms remained heavily invested in the strategy.

Attempts to alter workplace organization, much less close down uneconomical plants, were stymied by codetermination. Funding startups in new sectors was not the natural inclination of fusty banks accustomed to dealing with long-established customers engaged in familiar lines of business. And a proportional electoral system with a 5% threshold yielded unsatisfactory results and unstable coalitions when voters moved to the extremes, positioning the Alternative for Germany on the right and the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance on the left to earn parliamentary representation, while leaving the more moderate Free Democrats at risk of being shut out.

The solutions, it would seem, are obvious: Invest more in higher education and less in old-fashioned apprenticeships and vocational training so that Germany can become a leader in automation and artificial intelligence. Develop a venture capital industry to take risks that banks are unwilling to shoulder. Use macroeconomic policies to stimulate spending instead of relying on tariff-ridden export markets. Rethink codetermination and a mixed-member proportional electoral system that has outlived its usefulness.

Not least, release the “debt brake,” another inheritance from the past, which limits public spending. Doing so will permit the government to invest more in research and development and in infrastructure, two critical determinants of economic success in the twenty-first century.

Imagining such changes may be easy, but implementing them is not. Change is always hard, of course. But it is especially hard when one seeks to modify a set of institutions and arrangements whose successful operation, in each case, depends on the operation of the others. Attempting to do so is akin to replacing a Volkswagen’s transmission while the engine is running. …

The bad news, then, is that there is a serious mismatch between Germany’s current economic situation and its institutional inheritance, and that there are major obstacles to altering the latter to realign it with the former. The good news is that a crisis that prompts a wholesale rethink of that institutional inheritance could conceivably break the logjam. Maybe this is just the crisis that Germany needs.

Slightly heavy half hour

Question 7

I heartily recommend Richard Flanagan’s latest — a non-fiction book weaving together about eight or nine narratives all musing on the fact that his father wouldn’t have survived his Japanese prisoner of war camp if Hiroshima hadn’t been bombed. And Richard wouldn’t exist. A book of magisterial terrificness. Here’s a brief review of it and then an extract.

It is sobering, or at least produces a shiver of second-hand embarrassment, to think how badly such an idea might unravel. It’s easy to imagine a tawdry or vapid or absurdly self-important version of this book in which the author draws a line from himself to the excruciating deaths of hundreds of thousands of innocent people, taking in along the way a panicky literary romance, the Tasmanian genocide, Australia’s convict system and his complicated relationship with his grandmother. Posing unanswerable questions and dawdling over their unanswerability can come across as fey or annoying. Repeatedly drawing attention to the unreliability of memory and the ultimate uselessness of words as a means of conveying human experience can, in a book about memory and the chaos of human experience, feel like a cop-out.

Question 7, amazingly, avoids all of these yawning traps. It is thoughtful and often beautiful, moving without effort between the very big and the apparently very small. Flanagan is a riveting writer, whether he is describing the path to the creation of the atomic bomb or his mother pulling over to the side of the road so she could fill up discarded superphosphate bags with the red soil she remembers from her childhood.

The book is at its best when Flanagan takes his biggest risks, as in a chapter where he manages to pull together the government-sponsored extermination of Tasmania’s Aboriginal people, the death of the last Tasmanian tiger in captivity and childhood holidays spent in the Tasmanian rainforest, now almost totally destroyed: ‘For a long time I could not understand that it was possible to be both on the side that has the power, that has unleashed the destruction, vast as it is indescribable, and, at the same time, be on the side that loses everything.’

Richard Flanagan on King Rat

One of the few times I saw him get angry as a child was when the American movie King Rat was to be shown on tv over the summer holidays and we wanted to watch it. My father refused to let us. I saw it later at a friend’s home. Based on a highly successful American novel, King Rat tells of how an American POW prospers in the Changi POW camp by stealing from other POWs and running rackets and, as a successful criminal, becomes the de facto head of the camp.

My father said the camps weren’t like that at all, that it was an American idea, and anyone who’d behaved like the King Rat character wouldn’t have lasted. What he meant by not lasting he didn’t say. It was the first time I ever really knew anything about the camps and my father. When I asked if he had been at Changi, he said not really, which was true as he had only passed through it en route to the Death Railway. No one had heard of the Death Railway in those days. Even then my father’s world was not the real world which, it was evident from all the advertising around the Hollywood film, was that of a Hollywood film. My father despised King Rat. It was an American story. His was not.

His story was otherwise: we were told that on the Death Railway there was a POW camp of English not far from the Australians’ camp at Hintok where my father was, and there the English divided on class lines, the officers not working, keeping the small stipend the Japanese inexplicably paid imprisoned officers for themselves and surviving, the enlisted men labouring and starving and in consequence dying like flies. His words. The Australians, he told us, held together as one, the officers being compelled to pool their stipend to buy drugs and food for the sick on the black market, and working in the camp hospital and kitchen to help the group. Together they survived—or at least far more of them than the English.

That was his story and that much we knew growing up. You went under alone but together you could survive. When someone was down you helped, not out of altruism, but an enlightened selfishness: this way we all have a chance. The measure of the strongest was also the only guarantee of ongoing strength: their capacity to help the weakest. Mateship wasn’t a code of friendship. It was a code of survivors. It demanded you help those who are not your friends but who are your mates. It demanded you sacrifice for the group. Is that a convict idea? Is it an Indigenous idea? Is it both things merged? It’s not a European or an American idea. It is, though, a deeply old, serious idea of humanity.

A book on the Death Railway, an oral history, names my father. A survivor recalled how at the height of the dreaded Speedo—when the monsoon and cholera reigned, exhaustion was a prelude to death, and the Japanese demanded the starving POWs work up to sixteen hours a day, seven days a week—Japanese trucks would sometimes of a night become bogged on the treacherous jungle tracks. The prison guards would demand a man from each tent come to help push the trucks the last few kilometres to the camp, men who were already exhausted by their relentless labouring. As a sergeant, it was my father’s task to choose which man from his tent went. He always chose himself.

King Rat was, I only discovered many years later, written by an Australian named James Clavell who had been a POW in Changi. Clavell’s tale was published after a post-war career in English and then American movies. Written during a Hollywood writers’ strike in 1960 it seems to have been composed with a keen eye for an American market and sensibility and was an immediate bestseller. Perhaps it was Clavell’s experience, or perhaps it wasn’t, or perhaps he took those parts he felt would meld with American individualism and made of it a great commercial success.

When I asked my father about the story of him choosing a man from his tent to push the trucks of a night and my father choosing himself, he was annoyed. He said the author had it wrong and that the story was untrue. Yet previously he had told me it was a good book, and a reliable one. It was as though something in the story—beyond its veracity or otherwise—offended him deeply.

La Sagrada Familia is a marvel. So unique. So wonderful. It almost makes me tolerant of Catholicism.

Speaking on which, I thoroughly enjoyed Conclave. It’s just old men in dresses talking - but it is utterly riveting. Robert Barron obviously detests it.

Let’s keep ANU University House a secret. I have spent many happy hours at conferences there over the years and we stayed there for a family holiday once.