Meanwhile in an aspiring autocracy near you

And other highlights of my week poking around on the net

President gets army onside (Srsly!)

Though you may have seen it.

Please, please please tell me this is a deep fake.

A Bad Day for the U.S. Military

Donald Trump is going to say whatever he is going to say, apparently even when he’s speaking to a military audience. What matters more is how the soldiers respond to his most divisive and politicized comments.

Many soldiers—and thus, their commanding officers—failed that test at Fort Bragg yesterday (June 10). The boos and catcalls from uniformed Army personnel, responding to the President’s goading, were something with almost no precedent in U.S. history. It was alarming.

Listen to the troops boo the free press as Trump calls reporters in the crowd “the fake news.” [See clip above.]

Listen to the boos at the very mention of “the Biden administration.”

The former president gets more boos here:

Listen to the catcalls as Trump criticizes the previous administration’s upholding of transgender people.

[And so on.]

Soldiers are permitted to have personal political views, even on divisive issues. But because they fight for and defend the whole country, and because their institution cannot favor one party or faction over others in our democracy, they must avoid projecting political positions while on duty, in uniform. That goes for militaries in democracies anywhere in the world.

Many soldiers at Fort Bragg failed to do that yesterday.

Of course, many of them are young people—in their twenties or even younger—who probably haven’t been trained in the finer points of democratic civil-military relations. But you know who has received that training? Their commanding officers. The people who head their units. The generals and colonels in command at Fort Bragg. Those officers have been through courses—at the Army War College, at the National Defense University, at the Command and General Staff College, and elsewhere—where they have studied the importance of maintaining an apolitical armed force. Courses that include this content are prerequisites for their promotion.

Those officers had a responsibility to instruct the people under their command not to applaud nakedly political statements, and certainly not to boo legitimate, elected political leaders, not to endorse attacks on immigrants. They clearly failed to issue those instructions in a meaningful way, if at all. And they should be held accountable for this dramatic failure.

Edit 6:00PM: While I was drafting this, we got confirmation from military.com that the commanding officers at Fort Bragg set this up deliberately.

Internal 82nd Airborne Division communications reviewed by Military.com reveal a tightly orchestrated effort to curate the optics of Trump’s recent visit, including handpicking soldiers for the audience based on political leanings and physical appearance.

One unit-level message bluntly saying: “No fat soldiers.”

“If soldiers have political views that are in opposition to the current administration and they don’t want to be in the audience then they need to speak with their leadership and get swapped out,” another note to troops said.

This should be career-ending for those in command whose “leadership” led to this spectacle. If not, it’s “game over” for even the appearance of an apolitical, democratic military in the US.

The “more nuance needed” critique of Trump

Just as Elon goes thermo [sorry - this was written at the beginning of the week!], Henry Farrell nails his description of the emerging boilerplate of disappointed Trump fellow travellers.

As the Trump administration barrels into its second hundred days, the hard-working staff here at Spoiler Alerts has detected a new strain of punditry in the mainstream media. It first emerged among advocates of economic security. Folks like Oren Cass took to the New York Times op-ed page after "Liberation Day" to explain that that while their preferred tariff policy could still work to remake the U.S. economy, the Trump administration was admittedly making a hash of things with its actual tariff policies.

This kind of analysis can best be summed up with a simple rubric:

Trump's attacks on INSERT POLICY OR ACTOR HERE have some validity;

There are reforms that would improve INSERT POLICY OR ACTOR HERE;

Instead of enacting those valid reforms, the current administration is doing something that is radically counterproductive;

If they don't reverse course soon the mandate for change will be gone;

Remember, I had nothing to do with the current policy! My ideal approach has yet to be tried! ...

With this administration, however, there is some breathtaking naïveté involved in this kind of response. It presumes that there is a competent policymaking process at work that just needs some minor tweaking to be optimized. To repeat a theme, there is minimal evidence that there are any adults in the room and even less evidence that there are any competent political appointees minding the store.

For a recent example of this kind of delusional "if only they had read my oeuvre they wouldn't be in this mess" kind of take, let's take a look at the Manhattan Institute's Neetu Arnold. She has an essay in Politico entitled "Trump Is Right to Target Colleges. He's Doing It the Completely Wrong Way" that perfectly encapsulates this kind of intellectual exercise.

But in its conflict with elite universities, the Trump administration's urge to "move fast and break things," often without regard for the law, threatens to blow the first real chance for substantive higher education reform in decades...But right-wing authoritarianism risks politicizing the university even further — and that would eliminate the prospect of durable, long-lasting change that so many reformers like me are hungry for.

This essay has it all: the "both sides" equivalency, the "I write more in sorrow than in anger" tone, and the clear washing of hands of any culpability of current policy outcomes...

Arnold also suggests that, "the administration could change the criteria by which future grants are evaluated to avoid funding projects that are political in nature"... For example, new NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya tried to insist at an NIH town hall that Trump administration guidelines wouldn't affect real medical research — and then hit a brick wall of logic:

"As the program officer who oversees this research, I will tell you my studies have been terminated," an individual interrupted.

Bhattacharya clarified that studies into the effects of structural racism would be cut, to which the individual responded, "What do you think redlining is?"

Oops.

Back to Arnold's essay. The unintentionally hilarious portion comes in this section:

It's still early enough that the Trump administration can turn the ship around and effectively confront the very real issue of ideological capture in universities. But it needs to do so with precision, respect for the law and a long-term vision...Whatever the administration tries to pursue, de-escalation needs to be part of this strategy.

...these paragraphs in her essay fail to comprehend that this administration's inability to credibly commit to anything is not a bug but a feature. Pleading for the Trump administration to act in a precise, de-escalatory, planning-for-the-long-term manner requires:

A failure to observe the agglomeration of power within the presidency, making credible commitments next to impossible;

A willful amnesia of Trump's first 120 days in office.

A misplaced faith in Trump's subordinates.

A refusal to acknowledge the unpopularity of these policies.

My point is simple: policy wonks who hoped that Trump would be amenable to their reform ideas will inevitably be disappointed by this administration's recursive incompetence. Their fears that Trump's failures will collaterally impeach their preferred policy ideas are well-placed. And complaints along the lines of, "if only Trump would listen" will ring hollow.

Sunsetting solar eclipse

Ross Gittins on Labor’s superannuation scam

I haven’t added up the sums, but there’s a fair case to be made that Paul Keating did more to promote inequality in Australia than any other post war politician. After all we have:

cutting the top marginal tax rate rather than lifting the top threshold (as his successor did.)

dividend imputation - it took imagination to work out how to forego tens of billions of dollars in company taxation without lowering the cost of capital. But dividend imputation does it!

cutting company rates (which probably had to be done, but could have been paid for with lower company rates by keeping double taxation on dividends - as we have for many foreign investors.)

However having over $4 trillion of Australians’ savings subject to a largely flat tax takes the cake. The idea of compulsory savings makes some sense, but since you want to compel people to do it, what would be wrong with compelling them to save without giving them a tax break as well (to say nothing of how inequitable the concession is - it’s a tax break for the wealthy and a tax hike for those on lower incomes)?. And the idea of preventing young families’ investing their own savings in a house until they’ve paid their dues to the wealth management ticket clippers is a special touch.

Oh well, you can’t break an omelette without making eggs … or something like that. He’s some thinking aloud on the temporal mismatches involved by Ross Gittins.

Economists have long believed that the cost is passed back to the workers. And empirical studies have confirmed this. A study by one of the great experts in this area, the Grattan Institute's Brendan Coates, has found that, on average, about 80% of the cost is passed back to employees over the following couple of years. (Which raises an interesting point. Few if any commentators — including me — have thought to point out that some part of the cost-of-living pain working families have felt in the post-COVID period is explained by the government indirectly requiring them to increase their saving for retirement, thus leaving them less to spend.)

Between July 2021 and today, employees' super contribution has been increased by 2% of their pre-tax wage. In three weeks' time, that will increase to 2.5%. Of course, you'll get that money back, with interest, but not until you retire...

The worriers should remember this. Compulsory employer contribution started in 1992, at 3% of wages. This was gradually increased to 9% in 2002. As we've seen, between 2013 and next month, it will have gradually increased to 12%.

Get it? For older people, the more of their working years that have been in this century, the less cause they have to worry about not having enough. And for younger people, the more of their likely total of 45 years working that are ahead of them, the more the risk of not having enough should be the furthest thing from their minds.

Remember that the less you have in super, the more help you'll get from the age pension. But the more super you have, the less eligible you'll be for a part pension...

The big qualification to all that, however, is whether you own your home. Life can be a lot tougher for those retirees dependent on renting in the private market. Pensioners who rent get some assistance from the government — and more than they used to — but it can still be a struggle.

Remember, too, that it's easy for a person still working to overestimate how much they'll need to live comfortably in retirement. They'll be paying far less, if any, income tax. They won't be putting money into their super. They won't have dependent kids...

The more pertinent question is whether some young person who spends all or most of their working years getting annual contributions of 12% will retire with far more than they need to live comfortably – whether they'll end up living like kings (if they have the energy).

So here's the bad news: once you accept that workers actually pay for their employer contributions by receiving smaller pay rises over their working years, will they be forced to exchange a lower living standard while they're working for more money than they want to spend in retirement?

Saul Eslake on inequality

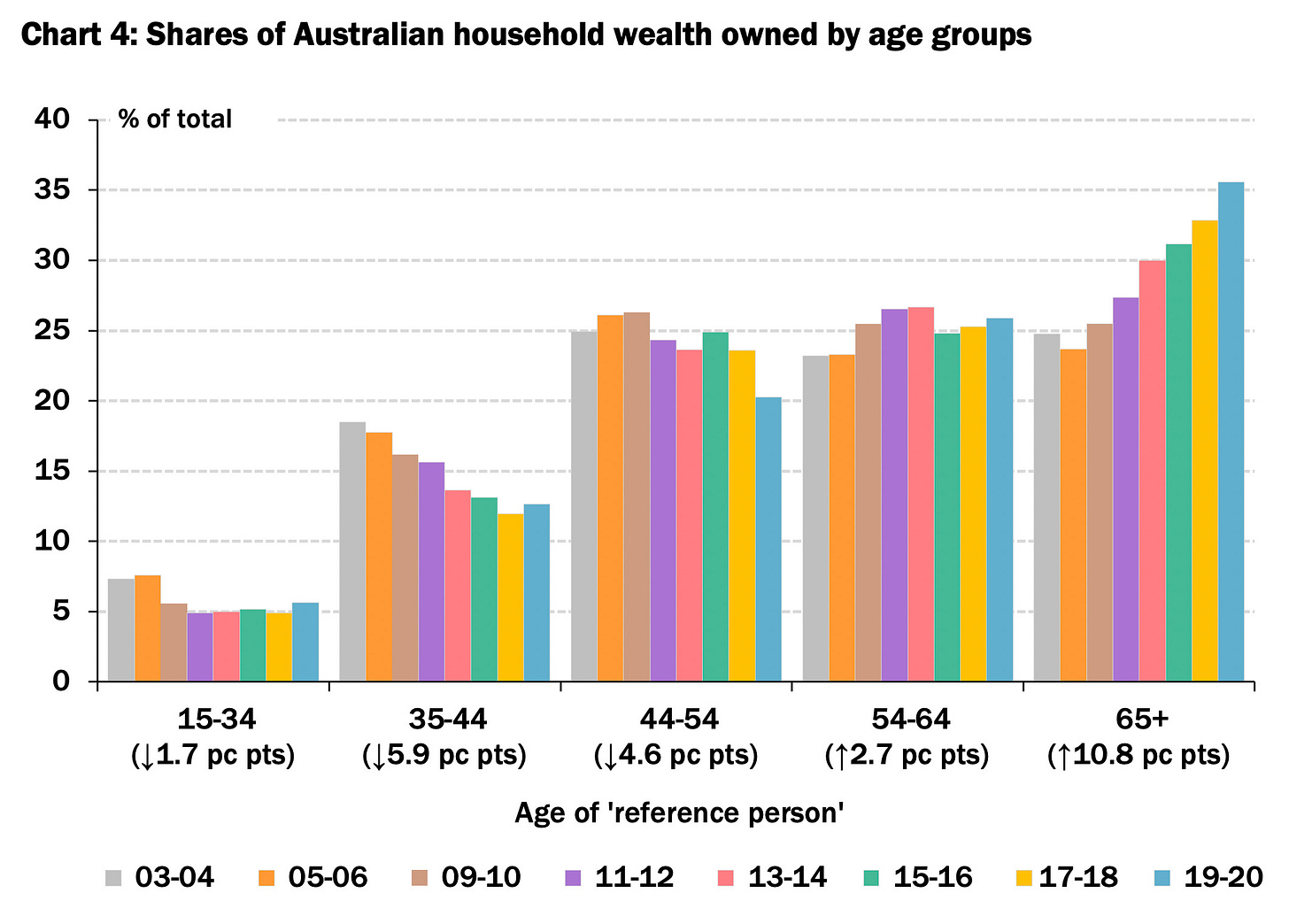

Speaking of screwing the young on behalf their older selves. A good article on inequality - particularly rising intergenerational and wealth inequality - by Saul Eslake calls for estate taxes on large estates. Certainly one of the fairest taxes around if you believe in equality of opportunity. But less so if you’re only pretending.

Mainstream Australian economists — including me — haven't thought, spoken or written as much about the causes and consequences of increasing inequality as perhaps we should have done.

International institutions including the IMF and the OECD have come to recognise that increasing inequality has adverse economic and political consequences...

Australia has done a reasonably good job of preventing the distribution of income from becoming more unequal. The share of total household income accruing to the top 1 per cent, or even the top 10 per cent, of households has actually declined over the past fifteen or so years...

to forty-four and forty-five to fifty-four fell by 1.7, 5.9 and 4.6 percentage points respectively between 2003–04 and 2019–20.

It is to be expected, of course, that older households will be richer than younger ones on average, since they have had longer to accumulate income and generate wealth... But the ageing of Australia's population doesn't go anywhere near fully accounting for the extraordinary increase in the share of household wealth owned by older households over the past two decades...

A particularly important contributor to increasing wealth inequality across age groups has been the decline in home ownership rates among younger households... [T]he home ownership rate among people aged between twenty-five and thirty-four fell from a peak of 61 per cent at the 1981 census to 43 per cent in 2021... [A] far more important factor has been the decline in housing affordability... it now takes someone on the median household income almost eleven years to accumulate a 20 per cent deposit on a median-priced dwelling, almost three times as long as in 1984.

Another important factor has been the series of conscious decisions by successive Australian governments to allow older people to pay less tax than younger people... Thus, in 2019–20, households where the reference person was sixty-five or older made up 25.5 per cent of the number of households, earned 16.7 per cent of total household income and owned 43.4 per cent of total household wealth — but paid just 7.4 per cent of total personal income tax...

What could be done to reverse this trend?

Given the role home ownership traditionally played in allowing a broad spectrum of the population to accumulate wealth and, in particular, secure some degree of security in retirement, the most important thing would be to reverse the slide in home ownership among younger age groups.

In recent years governments of both major political persuasions have adopted the view that the best way of reversing the deterioration in housing affordability is by boosting the supply of housing. Yet both major parties have been extraordinarily reluctant to back away from policies that inflate the demand for housing...

To curb increasing wealth inequality across age groups, governments should also reduce the concessional tax treatment of the types of income that disproportionately accrue to older and wealthier taxpayers — particularly the treatment of capital gains, dividends and superannuation earnings and payments.

Finally, governments could consider reintroducing some form of taxation of inheritances or bequests — especially given the scale of wealth likely to be bequeathed to their children by Baby Boomers, which some estimates put at almost $5.5 trillion.

Although such a tax would inevitably be depicted as "socialism" (or worse) by politicians and commentators across the spectrum, Australia is actually something of an outlier among OECD countries in not having any form of inheritance taxation... Given that some 64 per cent of inheritances in Australia go to people aged fifty-five or over, most of whom are already in the upper half of the wealth distribution, a tax on inheritances of more than (say) $3 million — with an exemption for surviving spouses or partners, and perhaps with some incentives for bequests to registered charities — would likely make a useful contribution to curbing the seemingly inexorable upward trend in the concentration of wealth in older and wealthier hands.

Increasing inequality in the distribution of income and wealth has adverse economic and political consequences. Economists should be doing more to bring those to the attention of the Australian public, and to propose politically workable solutions.

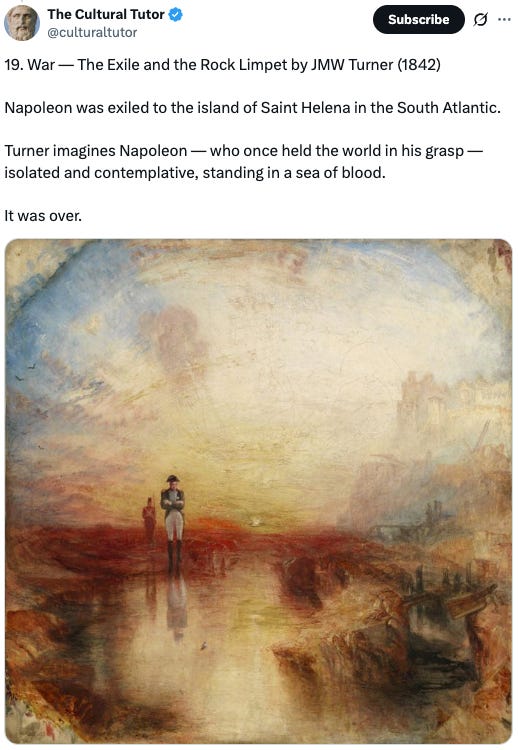

Did Horatio Nelson die in any of these chambers?

Hint: No.

Yes, folks you may have worked out that these are pictures taken inside musical instruments - particularly old and revered ones. By this fellow (Details here):

Not all pictures are taken from inside musical instruments

For instance …

Are you still on the right side of history?

A telling and timely piece from Venkatesh Rao. (I left out a long discussion on the importance of dealing with serious things without an element of unseriousness, which seemed to go on and on and I didn’t really get.)

Yesterday, my postdoctoral advisor from 20 years ago pinged me with a link to an Atlantic article mentioning a 2020 post of mine. It felt surreal, a recently closed chapter of my life colliding with a much older closed chapter. A certain clarity of purpose attended both those chapters (2004-06 postdoccing and 2007-2020 blogging). I knew what I was doing and enjoyed confidence that I was doing the right thing. That headspace feels surreal now. My shorthand for this feeling is being on the right side of history. It's a feeling I've lost in recent years, along with most of you. That doesn't mean I feel I'm on the wrong side. It means I can't see meaningful sides at all. History, winding through the Gramsci Gap, is non-orientable.

I take the phrase to mean right in both senses. There is a logic to history which creates inexorable tendencies in events that are useless to resist. That's the epistemic sense of rightness; being on the side that turns out true, increasingly validated by later events. There is also a moral arc to history that may or may not bend towards anything you care about, but it is important to stand with the things you care about regardless of what the arc is doing...

Some humans find themselves collapsing both senses of rightness into one, the hallmark of political extremism. We might define extremism as the belief that the truths of the universe must fully validate the particular moral positions you choose to adopt. That if you discover a complete-enough version of the truth, guided by your moral compass, you eventually won't need to adopt moral stances at all.

This attitude is characteristic of feeling on the right side of history. Extremism lies in clinging to that feeling even when the two senses of rightness begin to diverge. In choosing to risk being wrong rather than allowing yourself to feel wrong...

To be on the right side of history then, is to continuously update your sense of the boundaries of available moral choice space, while trying to get things epistemically and morally right within those boundaries. And accepting that you won't always get it right...

Now you could argue that everyone thinks they've stayed the same, while everyone else has become more "extremist" so let me offer a rubric. There is a simple test of who has shifted positions — if you still have a clear sense of the "right side of history" you've moved and turned extremist. You've let your attachment to the certainty possible in 2013 lead you astray. You want to know, and be on, the right side of history too badly.

The reason I believe I've stayed put while others have moved is that I no longer have a clear sense of the "right side of history" while everyone I've diverged from seems to have a stronger sense of what the "right side" is...

What makes Twitter and Bluesky/Mastodon equally surreal for me is not the toxicity and anger, but the high level of totalizing certainty. People who seem able to hold predictable positions on everything from Gaza and Ukraine to Trumpism, climate, and AI simply confuse me. They seem to conjure certainties out of thin air rather than from any superior understanding. I don't find them useful to be around...

As for me, I have abandoned all attempts to be on the "right side" of history, or to even map out sides. All my positions don't add up to a "side" I can characterize with simple labels, and I'm content to let them constitute nothing more coherent than a bag of atomized beliefs and doubts.

Walter Lippmann: the new bio

I’m a fan of Walter Lippmann, so it’s good to see his stocks have been given a boost by a recent bio which reassess his story (in a positive way). Here’s Geoff Shullenberger’s review.

There is a genre of popular media history that traces the rise of the propaganda-saturated reality we now inhabit to the influence of particular individuals who had novel insights into major shifts in communication technology...

The journalist and political theorist Walter Lippmann (1889-1974) is another frequent protagonist of such accounts. Critics on both the right and the left have portrayed him as a pioneering ideologue of elitist technocratic rule and a Svengali for the mass-media age. In the most influential work of progressive media criticism ever written, Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman's 1988 book Manufacturing Consent—which takes its title from one of Lippman's favored phrases—Lippmann appears as a founding theoretician and practitioner of the modern media's propaganda function...

There is no question that Lippmann was a towering figure in 20th-century American journalism and political commentary. In two books written in the 1920s, Public Opinion and The Phantom Public, he literally set the terms of debates about the media, propaganda, technocracy, and the role of elites in democracy that are still raging. In the first of those books, he repurposed the technical printing term "stereotype" to refer to the generic mental impressions gathered from media representations. He also popularized the phrase "the manufacture of consent," using it in a more neutral and descriptive register than Chomsky and Herman later would...

But a new biography by Tom Arnold-Forster offers a salutary challenge to what we can only call the stereotype that has often substituted itself for his complex legacy. "Lippmann's career," Arnold-Forster writes, "was not a one-note argument for the rule of experts; it was a six-decade commentary on the vicissitudes of politics." In their broad contours, the vicissitudes to which Lippmann was responding are still those of our own world. In his time as in ours, an increasingly complex political, economic, and social landscape and an ever-evolving array of media technologies posed fundamental questions about the viability of American democracy.

The starting point of Lippmann's thinking, Arnold-Forster explains, was the concept of the "great society" developed by the progressive British social theorist Graham Wallas, who was a visiting scholar at Harvard in 1910, when Lippmann was a 21-year old undergraduate there. In his 1914 book The Great Society, which he dedicated to his former student, Wallas began with the observation that the modern world was "a radically new environment." He attempted to apply the new insights of social psychology to the reality of the mass societies forged by the industrial revolution...

This concern became more acute for Lippmann during World War I. In this period, he worked for The New Republic, which ended up serving as the unofficial propaganda apparatus of the Woodrow Wilson administration, and also briefly for Wilson's War Department. In his 1920 book Liberty and the News, he reflected back on the implications of his experiences inside the state information apparatus, asking whether "government by consent [could] survive … in a time when the manufacture of consent is an unregulated private enterprise." The quandary prompted Lippmann to develop the key concepts for which he is remembered: not just "stereotypes," but "pseudo-environments," his term for the composite mental pictures of the world held by individuals...

Lippmann's question of what became of democratic citizenship under such conditions was the starting point of a long exchange with John Dewey, whose book The Public and Its Problems was a response to his books of the 1920s. This exchange is now remembered as the "Lippmann-Dewey debate," but Arnold-Forster argues that the standard account of it, in which Lippmann stands for technocracy and Dewey for democracy, oversimplifies their disagreement...

Just before the enshrinement of the Cronkite era as a lost eden, there was a brief period when many viewed the democratization of media by digital technology as the solution to the problems Lippmann first identified at the outset of his career...

Once the euphoria died, there followed a crude and futile attempt to reassert technocratic rule through the regulation of "misinformation" as well as an often equally crude backlash to that effort. The line of inquiry Lippmann pursued throughout his career—whether "government by consent [can] survive … in a time when the manufacture of consent is an unregulated private enterprise"—remains a vital one.

Is social media destroying young people’s capacity for love?

Self styled ‘reactionary feminist’ Mary Harrington featured this piece as a guest post.

The bed is empty, but my screen hums. Night after night, I scroll—half-dazed, half-hypnotised—through an endless stream of Instagram reels. My phone, ever-vigilant, distills my thoughts into an algorithm, feeding me a steady diet of avoidant attachment, situationships, red flags, and the ever-expanding lexicon of modern love's dysfunctions.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the comment sections under these posts are replete with twenty and thirty-somethings lamenting the state of dating today. But they are not limited to the libertines who drink the Kool-Aid of free love. No one is immune—not even the hopeless romantic.

I often wonder why even self-avowed conservatives are susceptible to the destructive forces of modern dating. One day, we scoff at our "liberated" peers and loftily proclaim traditional family values, yet the next, we find ourselves fulminating over our role as victims of the very dating culture we oppose.

We often lay the blame at the feet of the sexual revolution. But if young conservatives are consciously and sometimes even loudly critical of the legacy of the long '60s, and yet are still affected by the shifting sands of modern love, could there be something more amiss?...

Erich Fromm and Michel Houellebecq converge in a critique of the result: a consumerist logic that governs modern relationships, with corrosive effects on intimacy. In The Art of Loving (1956), Fromm argues that capitalist society encourages individuals to approach love as a marketplace, where partners are evaluated like commodities based on their perceived value and exchangeability. Similarly, Houellebecq's The Elementary Particles (1998) portrays a contemporary world in which sexual liberation and consumer culture reduce human relationships to transactional exchanges...

This erosion of love is not merely a byproduct of consumer culture—it is actively accelerated by technology. Marshall McLuhan, in Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), adds a critical dimension to this discussion by revealing how media shapes social dynamics...

One crucial critique is missing from the debate on our post-capitalist tech market: we rarely consider how the brevity and relentless form of social media itself might be warping our ability to love. Regardless of political or religious affiliation, a generation of twenty- and thirty-year-olds devotes hours to scrolling through Reels every day and is unaware of their psychological effects.

McLuhan distinguishes between hot and cool media, with "hot" referring to those which require little participation and "cool" those that require more input from us. Here, the "hot" media of online reels, provides a high-definition, immersive experience that demands minimal intellectual or emotional participation from viewers...

These media cast a shadow over the psyche of today's youth—including those who, despite the temptation of instant gratification, cling to conservative values. These reels, drenched in brevity and spectacle, have a way of distilling human connection into fragmented flashes of allure, demanding little more than a momentary glance...

If our brain patterns are rewired—our very biology altered—by constant digital inputs, we become increasingly vulnerable to forces that undermine long-term commitment. As dopamine cycles erode our capacity for sustained focus, even our deepest values may falter under the weight of unrelenting, ephemeral stimuli.

If I put my phone away, will it really matter? My hand will drift back to it, as if pulled by an invisible thread—a reflex I no longer control. The screen flickers to life, casting its pale glow across my bedroom as the reels continue—an endless cycle of theories, theatrics, and grievances.

As my fingers graze the screen, I lie to myself. If only we returned to tradition, we could escape the disarray of modern love. But neither nostalgia nor ideology will reverse what has already been set in motion. We are all trapped in the same current, and the truth is laid bare—unlike the intimacy I've learned to fear. No, we did not abandon love; we have been rewired to be incapable of attaining it, let alone holding onto it.

Look what my YouTube algo is turning up

Heaviosity half-hour

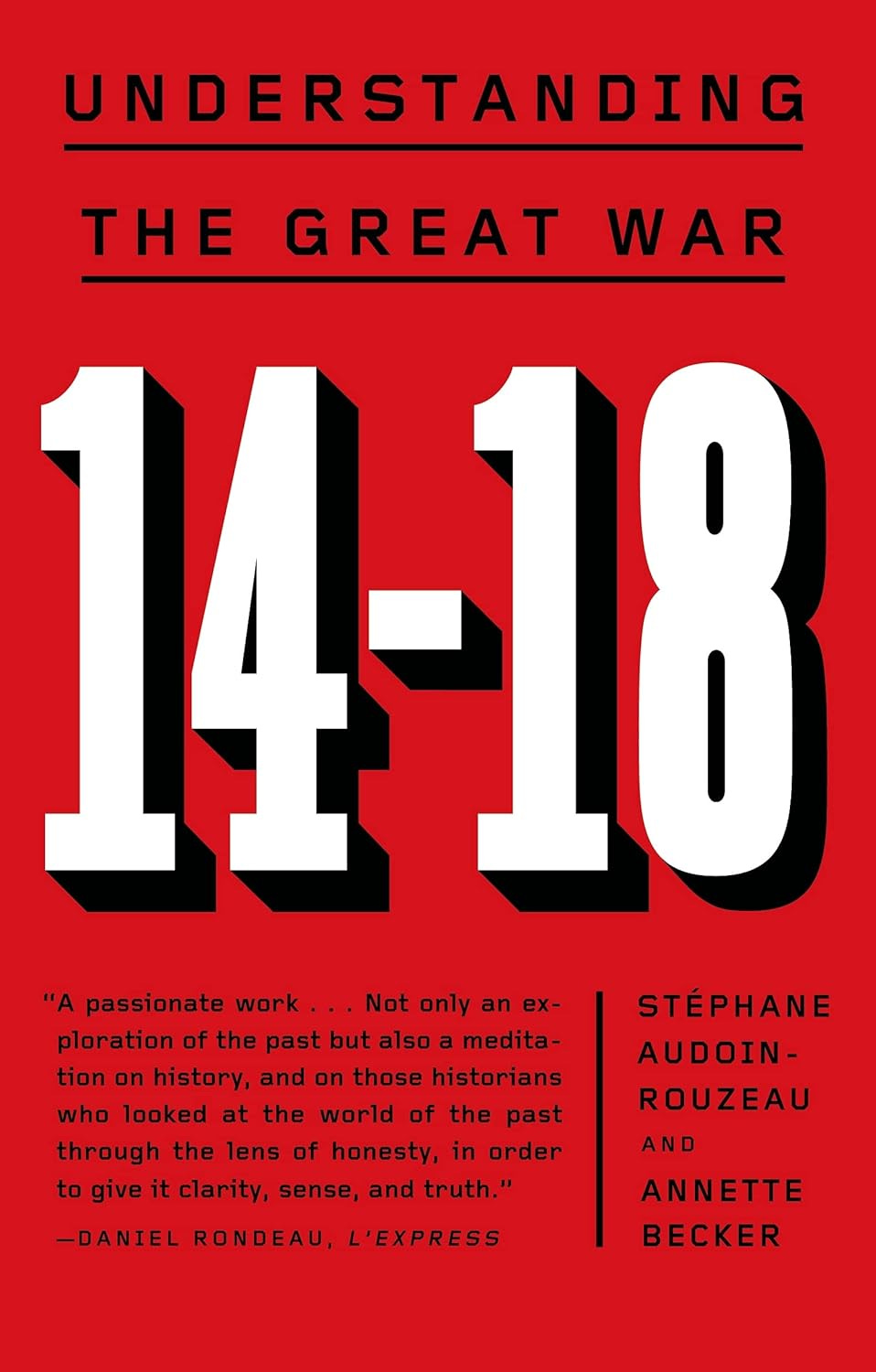

14-18: Understanding the Great War

I ran into this book in a remainders tray in Manuka, ACT. It was well worth the read.

Introduction

Understanding the Great War

The Great War, because it was both European and international in scope, because of its long duration, because of its enormous and long underestimated effect on the century that followed, has become a paradigm case for thinking about what is the very essence of history: the weight of the dead on the living.

In November 1998, eighty years after the signing of the armistice, West European countries saw a marked increase in the number of commemorations of the Great War in which various approaches were superimposed -- historical, memory-related, political, journalistic and audiovisual, sometimes contradicting, sometimes substantiating one another. Invoking the 'duty to remember' and often forgetting the obligation to history, people experienced a spectacular return of the Great War to the collective consciousness...

The commemorative writers and speakers caused great intellectual confusion by going to extraordinary lengths to stress the victimisation of the soldiers: not only were the combatants depicted as mere non-consenting victims, but mutineers and rebels were called the only true heroes. Hadn't the mutineers of 1917 been, in a sense, the precursors of the European Union? And hadn't the Nivelle offensive been the first 'crime against humanity'? We could give many examples. The failure to treat history as History reached new heights. In a century of total war everyone is so afraid of not having suffered enough that 'competition among victims' becomes urgent and the vocabulary becomes inflated. There are people who believe that thinking like this shows their humanism.

Obviously we should move towards a history of the war that shows greater empathy for all the actors involved and that comprehends their suffering (that of women, men and children, Europeans and non-Europeans), but fine sentiments must not be confused with intellectual analysis...

Actually the intellectual confusion of the Great War commemorations was superimposed on a long tradition. A peace-loving, indeed pacifist, ideology about the war to end all wars had prevailed for a long time. More was written (and fantasised) about the Christmas truces and the fraternising among enemies than about their hatred of each other. And it is easier, however painful, to accept the idea that one's grandfather or father was killed in combat than that he might have killed others. In the context of personal or family memory, it is better to be a victim than an agent of suffering and death. Death is always inflicted, always anonymous, never dispensed: one is always a victim of it. Or a victim of one's leaders, who are then promoted to being organisers of a massacre. By transforming combatants into sacrificial lambs offered to the military butchers, the process of victimisation has long impeded thought, if not prevented it, and much of what was said in November 1998 is the consequence of this. Hence the essential question of why and how millions of Europeans and Westerners acquiesced in the war of 1914--18 has remained buried. Why we accept the violence of warfare has remained a taboo subject.

The 1998 commemoration resulted in another, more positive, 'achievement', however. It seemed that the pain of bereavement, the pain of lost love experienced by families, which had been so difficult to express right after the war and which historians had considered so difficult to apprehend, suddenly resurfaced during those anniversary weeks...

Retrospectively, therefore, we can see the commemoration of the eightieth anniversary of the 1918 armistice as the symptom of a growing 'presence' of the Great War. Indeed, everything suggests that '1914--18' has been given a new lease of life. And although France is the country where this phenomenon is most clearly apparent, it is also manifest elsewhere...

An opinion poll assessing respondents' spontaneous views of the history of the twentieth century, conducted in France on 6 and 7 November, 1998, gives an interesting hint as to how the major events of the past century, including the Great War, were rated. As might be expected, the Second World War was ranked first in importance, followed by the student movement of 1968, and then the collapse of the Soviet Union; fourth was the Great War...

The rankings are even more significant when the results of the poll are grouped according to the respondents' ages. Then we have quite a surprise: people over 50 ranked the Great War lowest, followed by people aged 35--50, and finally by people under 35; better still, the youngest group polled, 15--19-year-olds, ranked it second. Thus the younger the group, the more they saw the war of 1914--18 as an important event in the twentieth century; the fourth generation, whose great-grandparents lived through the Great War, had selected it by an overwhelming majority. In other words, it is as though the time that has passed since the war were irrelevant; the Great War tends to be ever more present in the minds of successive generations.

For any historian of the First World War, however, this result is more of a confirmation than a surprise. It is one more indication among many that, since the early 1990s, and in France particularly, the Great War has been increasingly important; the 1998 commemoration only confirmed this...

The eightieth anniversary of the armistice in 1998 marked countless initiatives on the part of local communities, town halls and schools: never had the desire to know about the 'public history' of the war been greater, and never before did it have such success. The historian Henry Rousso has written about what he calls the 'trop-plein du passé', a paralysing obsession with the past. But professional historians specialising in the Great War have been for many years seeking new approaches to the study of the conflict, using anthropological and cultural insights, which is another sign of how present the matrix event of the twentieth century still is...

First, we should remember the surprising re-shuffling of the international cards, since this was the context in which the war was recollected in the 1990s. The fall of the Soviet Union and attendant events opened new distancing possibilities, of which the historians involved in the creation of the Historial de Péronne were fully aware at the time. As one of them, Jay Winter, liked to say, 'The war of 1914 is over.' The statement must be given the same meaning it had for François Furet when he said of another matrix event, 'The French Revolution is over.' Indeed, 'the end of the Great War' was becoming an evidence in the early 1990s with the death of the last veterans, whose stories had allowed the experience to be handed down through families but simultaneously kept it from being historicised. Most important was the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, which meant that one of the last and most dramatic political, ideological and geopolitical consequences of the First World War seemed to be fading as well...

But this was a fleeting time -- an illusion. Very soon, in the vacuum left by the decline of Soviet communism, Europe began to see a return to various aggressive forms of nationalism. This was mostly the case in Eastern Europe, although Western Europe did not remain unscathed. In 1992, for the second time since the summer of 1914, Sarajevo was in the news. When war broke out in the former Yugoslavia, a link was re-established with the Balkan conflicts of 1912--13 and, of course, with the European crisis of July 1914. From then on, war throughout Europe, though never a direct threat, seemed again within the realm of the possible. An enduring historical link was reestablished with the Great War and its Balkan epicentre, the very scene where the logic of war had been set in motion in the summer of 1914. The roots of the century were re-emerging -- and now could be better understood...

Paradoxically, the Great War had for a long time brought with it a kind of oblivion about one of the essential features of wartime, the weight, as we have said, of the dead on the living. It might at first seem shocking to say this, given the huge amount of commemorative activity that went on in the period following 1918 and still vigorously continues to this day. But wasn't the primary goal of these commemorations to exorcise death and help the survivors overcome the grief of bereavement? In this sense, with their emphasis on death in combat, the commemorations in fact partially repressed one of its main consequences -- the pain of bereavement.

It is striking that until very recently, mourning was scarcely an object of study among the historians issued from the nations that had experienced the war and mass death. No one has calculated the extent of what one might call 'the circles of mourning' that the deaths in combat created within the belligerent societies. But even very tentative estimates show that mourning occurred on an immense scale. For example, in France, if we apply the concept of 'entourage' that modern demographers use, we can estimate that two-thirds or even three-quarters of the population were affected, directly or indirectly, by bereavement or, more accurately, bereavements. Young people had died violent deaths, having suffered unprecedented mutilations of the body. Their families often did not even have the corpses of their loved ones to honour. So the mourning process was complicated, sometimes impossible, always protracted...

It is not clear that the former belligerent nations have completely recovered from this mourning or from the distress that its lack of meaning engendered. The concepts of infinite mourning, or interminable mourning, borrowed from psychiatry, are perhaps relevant in describing the particular relationship French society, for example, still has with the Great War, given its immense emotional investment in the conflict and the equally huge sacrifices it agreed to...

However, this hypothesis seems to contradict another phenomenon which the 1998 commemoration showed most eloquently, namely, the breach in understanding. The system of representations which characterized First World War contemporaries -- soldiers and civilians, men, women and children -- is now almost impossible to accept. The sense of obligation, of unquestioned sacrifice, which held most people in its tenacious, cruel clutches for so long and so profoundly, and without which the war could never have lasted as long as it did, is no longer acceptable. The foundation on which the immense collective consensus of 1914--18 was based, particularly in France, has vanished into thin air...

During the war, articles appeared in religious magazines warning readers against the 'superstitions' that had been proliferating since the beginning of the conflict. Both priests and anthropologists tried to understand these phenomena. A Swiss questionnaire that circulated in Italy and France shows the great diversity of spiritual approaches as well as the observers' lucid understanding of them:

[1] What means are used to shirk military service (mutilations, superstitions, etc.)?

[2] Does recruitment involve any particular practices?

[3] Are you aware of strange practices during and after battle (symbolic practices during the declaration of war, the throwing of earth over the head; where and when...)?

[4] How is it believed that life can be saved? Are some people considered invincible? Holy objects, holy water, coins or medallions (images and inscriptions?), religious maxims; magical notes, amulets, plants and other magical objects.

[5] What are some of the popular remedies used to calm or dissipate certain illnesses?

[6] Are there inoffensive or superstitious ways of always reaching the goal (hitting a target or an opponent)?

[7] What are the omens of war?

[8] Do the people believe in prophecies relating to the war, the destruction of princely families or countries...?

In the prayer-amulets that soldiers wore, often sewn into the linings of their uniforms, in the prayer chain-letters, in the prophecies, and in the numerical puzzle games played in France and Italy, the German empire was always defeated mathematically...

We are therefore confronted with a strange paradox. The presence of the Great War in our lives is due to two developments: on the one hand, a feeling of proximity because of its re-emergence on the international political scene and the reappearance of mourning; on the other, a feeling of estrangement, due to the more distanced historiography and a lack of references that might help us understand it, though it is now a subject of permanent questioning for which there are no satisfying answers. It is as though we wished to understand the Great War more than ever before without being sure of ever having the means to do so. Therefore, it seems all the more essential that we take a fresh look at it.

Perhaps it is not irrelevant briefly to clarify our personal backgrounds. We were both born at the end of the French war in Indochina, and our first 'war memories' were of the Algerian War, which came to us as scattered, mostly unintelligible images. We belong to a generation that has no immediate connection with the activity of war -- possibly the first generation of this kind in Europe since the eighteenth century -- unlike our contemporaries in the United States, who have had direct knowledge of the Vietnam War. War was within the realm of expectations, or in the memory, of our great-grandparents, grandparents and even parents, when they were children or adolescents. But we are the children of the West's disengagement from war. Does this mean that we have a cold, disembodied view of our object of study? Certainly not. The Great War is still a source of powerful emotions, but our feelings can't be of the same kind as those that gripped the witnesses or the sons and daughters of witnesses. We could feel this tension in our early childhood as we stood before monuments to the dead, when a great-uncle or grandfather 'who had done Verdun' recounted the horror, the terror and the patriotic feelings. Then the 1970s and 1980s swept away that version of the war for good. Like it or not, the umbilical cord was severed.

Our way of writing about the Great War is closely linked to our museum experience at the Historial de la Grande Guerre in Péronne. This project brought together an international team of specialists, made up of both former allies and former enemies, who met in the mid-1980s and created a centre for international research in 1989. The museum opened its doors three years later. Thanks to the very generous support of the Conseil général de la Somme, fifteen years of team work -- museographic work, research and publications -- were undertaken in an atmosphere of complete friendship and intellectual enthusiasm...

The raison d'être of this book is to offer a way to understand the Great War. The reader will have guessed from our introduction that we intend to explore the three pathways that we feel are most likely to lead to the heart of 1914--18 -- violence, crusade and mourning -- and that this study is the synthesis, indeed the outgrowth, of collaborative historical efforts. We should like to thank those friends, far more experienced than us, from whose immense knowledge we have benefited for so many years. We are fully aware of our debt to them.

VIOLENCE

Everyone knows war is violence, and though many readily acknowledge this, they refuse to draw the inevitable consequences. The history of warfare -- particularly academic and scholarly history, but also traditional military history -- is all too often disembodied. Why such a shortcoming is especially serious when it comes to the First World War is something we shall try to explain. But it might first be useful to consider briefly the reasons for so much reticence and to try to get to the root of this unacceptable way of sanitising war. Alain Corbin has said about the history of sexuality, 'An obvious puritanism has, until very recently, weighed heavily on university research.' This harsh but we think justified statement can just as well be applied to the historiography of warfare, especially that of the Great War.

Battle, combat, violence: a necessary history

The violence of war inevitably takes us back to a history of the body. In war, bodies strike each other, suffer and inflict suffering. So the reticence of historians over the violence of warfare is connected to the reticence that has long attended a genuine history of medicine (military medicine even more so). Here again Corbin is right when he notes that any history of bodily suffering engages historians. They expose themselves not only to their readers -- far more, certainly, than is the case with other kinds of history (with the possible exception of the history of sexuality) -- but also to the specific pain associated with the subject matter. Propriety, together with an understandable need for personal security (not to mention academic security), are at the root of the widespread, long-standing reticence of many French historians who have chosen to study the violence of warfare.

'Annales historians' in the narrow sense of that term tended to discredit the study of actual warfare, of battle, and caused damage with their hostility to 'histoire-bataille', or battle history. Actually, the battle history that the Annales founders decried was anything but an actual history of what went on in battles. And Marc Bloch himself, one of the founders of the Annales, was a marvellous historian of combat in both world wars. But in any case, the violence of warfare belongs only outwardly to what Fernand Braudel somewhat condescendingly described as 'history that is restless' for it touches on the essential in the history of mankind. If the aim of historians is to start with people, and to undertake a 'history from the bottom up', as the Annales school believed, who can deny that for the men who have lived through wars and survived them, wars and their violence have been the most important experiences of their entire lives? One should note the immense need for self-expression that warfare has always aroused, from the Napoleonic wars to more recent conflicts. It was in order to recount their experiences of war, describe its violence, or at least try to say something about it (the great majority never succeeded in verbalising it) -- or just to leave behind a humble trace of it, if only for their descendants -- that, from the late eighteenth century on, so many warriors took up the pen, sometimes for the first and last time in their lives. And to neglect the violence of war is to neglect all those men who in growing numbers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries endured that immense ordeal.

Of course, military history has always existed, in every country. But all too often military historians consider it indecent to deal with the problem of violence in combat or to study it as such. Battles and warfare are discussed only from the tactical or strategic angle; military events are viewed only from a social or political standpoint. On the whole, the reality of war is kept at bay. As a rule, French historiography of warfare has been unconcerned with the violence of the battlefield, the men in the arena, the suffering they endure, the perceptions of the men who try to survive and, in a nutshell, the immense stakes that are crystallised in the combat zone.

Avoiding these issues is an error. The violence specific to warfare is a prism that refracts many otherwise invisible aspects of the world. Entire societies can be seen anew, but one must be willing to look closely. In paroxysms of violence everything is stripped naked -- starting with men, their bodies, their fantasies and desires, their fears, passions, beliefs and hatreds...

In Britain, John Keegan... is among those who has delved deeply into the wide-ranging problem of warfare. Plainly challenging Clausewitz and his overrated dictum that war is 'the continuation of policy by other means', he states a deep truth: war is first and foremost a cultural act.

In his major work, The Face of Battle, Keegan daringly focussed exclusively on violence, in defiance of the discipline's most established rules of caution; he aimed for a diachronic comparison among the battles of Agincourt, Waterloo and the Somme, investigating the attitudes, behaviour and systems of representations prevailing in each. Not only his approach but the content was original, for what interested Keegan was precisely what no one had usually been interested in: behind the words used in the conventional accounts, he asked, behind the meaningless expressions everyone used, what exactly is happening on the battlefield, in the opaque sphere of interpersonal violence? Indeed, he tried to focus, to use one of his other expressions, on a 'history of flesh'...

It is striking how much historians, though they profess to be discussing war, are cut off from areas of relevant knowledge. Weapons, for example -- how they are used, how they work, and what effect they have -- are outside the competence of most of them, while military historians who may be learned about weaponry don't know how to apply their knowledge. So one cannot exaggerate the value of having at least some concrete knowledge of the instruments of violence; tactile contact with them is not a superfluous historical experience. Objects lead to objections, as the etymology hints; they stand in the way of the most established historical certitudes...

For instance, there is a highly specialised expertise (which would merit historical studies of its own) among military collectors and battlefield enthusiasts. But this generally reliable erudition, which has spawned journals, specialised books, meetings of devotees and networks of buyers and sellers -- a very useful body of knowledge for professional historians, which they would be hard put to find elsewhere -- is almost completely cut off from academic scholarship. This reaction on the part of 'scholarly' historians stems from distrust, indeed denial, mixed with a touch of arrogance. With chilling humour, Keegan recounts how he once offended the curator of a war museum:

I constantly recall the look of disgust that passed over the face of a highly distinguished curator of one of the greatest collections of arms and armour in the world when I casually remarked to him that a common type of debris removed from the flesh of wounded men by surgeons in the gunpowder age was broken bone and teeth from neighbours in the ranks. He had simply never considered what was the effect of the weapons about which he knew so much, as artefacts, on the bodies of the soldiers who used them.

But historians of war may be no more aware of these things than the curators of military museums.

Thresholds of violence in the Great War

Reticence in discussing violence is particularly unfortunate in the case of the Great War, for one important characteristic of this four-and-a-half-year conflict is its unprecedented levels of violence -- among combatants, against prisoners and, last but not least, against civilians...

The death toll of the Great War is well known: around 9--10 million, nearly all soldiers. Looking at the total mobilisation figures, we find that the smaller nations were proportionately most affected, given the techniques of warfare used in the Balkans already in 1912--13; the treatment of the wounded and of prisoners, as well as the inadequacies of medical procedures, greatly contributed to the losses...

Perhaps because they are of too great an order of magnitude, or because they have been cited so often, or perhaps because when we are confronted with such statistics of war, powerful reflexes kick in to make them seem unreal, these numbers, oddly, are a weak evocation of the horror. This changes if we adopt a different, less frequently used scale and count the number of dead in relation to the days of war. Taking just the two powers most affected, we can say that on average almost 900 Frenchmen and 1,300 Germans died every day between the outbreak of war in August 1914 and the armistice in November 1918...

Surprising as it may seem, when we compare the average number of daily casualties in 1914--18 to the average number in the First and Second World Wars, we find that the mortality rate is almost always higher for the First...

Some of the peaks of violence are especially revealing: on the first day of the British offensive on the Somme, 1 July 1916, 20,000 men from Britain and the Dominions were killed, and 40,000 men were wounded. No day in the Second World War was so deadly, even on the Eastern Front. For today's Western societies, which are relatively unfamiliar with death, and even with the idea of death in war, it is extremely difficult to begin even to imagine the meaning of such numbers.

True, mass carnage in war was nothing new. In fact, total war losses in Europe during 1792--1815 were comparable, proportionately, to those of 1914--18, though of course spread out over more than twenty years. Furthermore -- and this is probably the most significant difference -- the cause of death changed in the span of a century. In the early nineteenth century, disease killed more men in wartime than combat did. The numbers were about equal fifty years later, for the first time, in the Italian war of 1859. A half-century later, in 1914, the situation had reversed: deaths in battle were almost exclusively violent ones, even though the number of sick soldiers remained very high...

Not only did the nature of death during combat change in 1914--18, but so did the nature of the injuries. In the French army, 3,594,000 injuries were counted and 2,800,000 wounded. Half the men were wounded twice and more than 100,000 three or four times. The ratio of wounded to mobilised men is thus around 40 per cent, a proportion that was typical for all the large armies engaged in the conflict. This change in the violence of warfare involved first the bodily flesh of the fighting men, both victims and witnesses; combatants in earlier times had never seen injuries of that kind and on such a scale, either on themselves or on the bodies of their comrades...

The war bereavements of 1914--18 had other tragic features. Only the wounded who were hospitalised could be visited by relatives before they died; in the great majority of cases, no relatives were present to attend to the dying men in their final moments. So the soldiers often died alone, and if not alone, almost always without the support of close family members. All the stages that prepare a person for bereavement were thereby eliminated, as were all the rituals that ordinarily accompany the first moments of loss. And what was especially cruel for the people bereaved by the Great War was that they lacked the bodies of those who had died.

After 1918, as we know, the bodies remained on the battlefields in military cemeteries established in the combat areas. The Americans and the French were the only ones who by national law or decree had the right to request that bodies be sent home for private burial. The movement to have this happen didn't begin until the summer of 1922 and culminated, after several years, in the repatriation of nearly 240,000 coffins, which is about 30 per cent of the 700,000 identified bodies whose families were entitled to ask for them -- a significant proportion...

The grief of bereavement was increased by the recurrence of loss. The length of the conflict and the number of dead often led -- though it is impossible to cite numbers -- to multiple painful bereavements. The case of General Castelnau, who lost his three sons in the war, was famous in France, but it was not unusual. The four sons of Paul Doumer, the French statesman who was later President of the Republic (and assassinated in 1932) were all killed...

The lack of details about the fate of loved ones was another characteristic that countless tens of thousands endured in the 1914--18 war. Its unique conditions of combat increased both the number of missing and the number of unidentifiable bodies for all the belligerent parties. In France, half of all the corpses were in this category. The relatives were not able to have a grave or burial place where they could grieve and begin their mourning; they had only the ossuaries, like the one at Douaumont, or the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. This deeply traumatised them. 'The symbolisation of the dead person is fundamental, by whatever means: a grave, a cenotaph, or something that belonged to the person,' writes a specialist on this subject. 'The metonymy ... in other words, the shift in meaning from the thing contained to the container (from the corpse to the tomb), is essential for mourning: it allows the living to focus their grief on a support that gradually becomes a substitute for the body of the deceased.'

For relatives, knowing of the soldiers' enormous suffering of mortal agony on the front added yet another torment. Families could well imagine that suffering, just as they could imagine their dying sons' animal solitude and anguish...

'Civilising process' or 'brutalisation'?

War violence on such a scale, and perpetrated by such large sections of European society for the first time during 1914--18, should contradict the attractive idea that social violence in Western civilisation since the early modern era slowly ebbed away -- an idea for which we are indebted to the German sociologist Norbert Elias. Historians studying the nineteenth century have also stressed the spectacular decline of violent practices in the social body as a whole, emphasising the progress of the 'long and difficult work of in-depth self-containment achieved by human beings' -- as revealed, for instance, in the growing rejection of all spectacles of massacre, in the progress of analgesic techniques and anaesthetics, and in the individual and collective participation in the cult of the dead.

The argument that violence gradually decreased meets with one main objection, however: the phenomenon of war. Indeed, war is not really included in Elias's scheme, or only in a cursory way, as for example, in his depiction of medieval warfare, the accuracy of which has now been shown to be uncertain. As for the First World War, which took place twenty years before his major work was published, he seems not to consider it a serious obstacle to his thesis about a 'civilising process' except in one respect: it does not escape him that the increasing refinement of table manners since the beginning of modern times suffered a sudden setback on the battlefields of 1914--18; the men swiftly and easily reverted to practices that had vanished from the Western world centuries before. Elias explains:

Retroactive movements are certainly not inconceivable. It is sufficiently known that the conditions of life in the World War I automatically enforced a breakdown of some of the taboos of peacetime civilization. In the trenches, officers and soldiers again ate when necessary with knives and hands. The threshold of delicacy shrank rather rapidly under the pressure of the inescapable situation.

But for him this was only an 'incident' that could not invalidate the general 'line of development'.

In fact, Elias preferred mostly to disregard the Great War and failed to give it its proper place. Yet one cannot deny that it left visible scars, particularly in his native Germany, where one could not avoid the sight of mass mourning and of mutilated veterans and men with facial wounds -- like the ones painted by George Grosz and Otto Dix. But for Elias, while the 'civilising process does not follow a straight line' and 'on a smaller scale there are the most diverse crisscrossing movements', nevertheless, 'if we consider the movement over long periods of time, we see clearly how the compulsions arising directly from the threat of weapons and physical force gradually diminish, and how those forms of dependency which lead to the regulation of the affects in the form of self-control, gradually increase'. However, the violence of the First World War and of subsequent twentieth-century wars cannot be regarded as small-scale minor accidents.

Yet war as waged in the Western world in the twentieth century has rarely been acknowledged to contradict the presumption that there has been an 'advance in the threshold of repugnance' in the modern period, an advance that might seem at first to have reached its peak in the nineteenth century. For after all, the experience of the violence in the 1914--18 war gave contemporaries the impression that, throughout Europe and in all nations, the apparent 'dynamic of the West' had been snuffed out. And this radical and radically new violence was not only massively accepted by the belligerent societies but also implemented by millions of men over four and a half years. Even more troubling, the about turn -- from a social state where violence had become very controlled, repressed and unreal to a state of war where extreme violence had free rein -- occurred in an extremely brief span of time. In a matter of days and with hardly any transition between the two, Europeans who had benefited from the 'civilising process' left their work, their families and their often sophisticated, cultivated social life to accept extreme violence...

Death and mourning were such completely repressed themes after the Great War, their existence was so pervasively denied, that they almost became socially invisible. The diagnosis of this 'interdict laid upon death by industrialised societies', as Philippe Ariès called it, was made years ago by Ariès himself and by the anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer. It is not unreasonable to suggest that this taboo also affected how historians have viewed the Great War.

Gorer was probably the first person after the Second World War to grasp, in studying his own country, not only the Western taboo on death but also the influence of the First World War in creating it. In an autobiographical preface to his work, written in 1963, he mentions a strange development: in 1915, when he was still a child, he noticed that mourning clothes were increasingly frequent on the street, so that his widowed mother 'no longer stood out in the crowd', but then quite unexpectedly they became rare in 1917--18. It would seem that a sartorial ritual of mourning subsided just when the number of bereaved was on the rise. This was not merely a child's impression; a specialist noticed a decline in the use of black clothes in France and Great Britain starting in the middle of the war: 'It was the terrible slaughter of the First World War that undoubtedly caused the major breakdown in funeral and mourning etiquette.' Another scholar believes that 'one thing is irrefutable: the rituals of mourning fell apart in a continuous process that can be traced back to the period just after the First World War'. An ostentatious display of mourning seemed increasingly inappropriate as the mass slaughter of the Great War continued...

Battlefield violence and things left unsaid in the history books

We have stressed that the violence of combat must be fully disclosed because historians have for too long sanitised this aspect of the Great War, to the point of making it all but incomprehensible...

It was not unusual for soldiers on leave to feel that they should visit the relatives of a dead comrade. The writer Maurice Genevoix remembers it with horror in a book written more than half a century after the war:

When misfortune strikes, each one of us experiences his suffering alone. But on that day ... between Benoist's father and mother, it seemed to me that I felt -- it even flowed through me -- the grief of the parents of a soldier who had been killed ... Between his rare words, the father let his eyes wander in the distance ... And suddenly his jaws would tighten, and I could see the muscles tremble. The mother stared at me constantly. And then I had to look away. What I saw in her eyes was in the end unbearable to me.

These two texts demonstrate the same thing; it is striking how strongly this primary group carried their memories of the dead. Everything we know about the conversations among soldiers shows how frequently the survivors talked about those who had been killed; in personal notebooks, for example, the other men's deaths are very present. Even first-person accounts composed after the war show this; the comrades who were killed in the war are named, described, written about at length; very often, the narratives are dedicated to them.

Just this morning in an interview by Chris Hedges with Patrick Lawrence there was a comment not necessarily so positive about Lippmann and Dewey (which I have forwarded to Patrick) - so I was interested in reading it - and the reference to Bernays - a cousin of whom I met a decade ago in Tamworth where he was the pastor of 3Cs church... I enjoyed the Shaun Micallef piece and the one which followed on - on YouTube - about Michaelia Cash!!! The painting with the man on the forested islet reminds me somewhat of a photo I took many years ago of a pine tree covered islet on a highland's lake in Scotland and another about 13 years ago on Chappaquiddick Island (a short ferry ride from Edgartown on the north-east tip of Martha's Vineyard). There was no man standing on either of the islets I photographed.

I met Bernays' sister - Judith Heller (nee Bernays) in Santa Monica in 1967 - she was the great friend of my great aunt Lily with whom we stayed for some weeks. I was ten and heard she was Freud's niece - which didn't mean a lot to me at the time ;)

She wrote about her grandparents - Sigmund Freud's parents here. https://www.commentary.org/articles/judith-heller/freuds-mother-and-father-a-memoir/

Meanwhile the Freud genes just keep on rolling, they keep on rolling through British life through Anna, Lucian and now Esther Freud the novelist.