Rhyming with the F-word

I expect, to the shock of the audience, Martin Wolf described Trump as a fascist at the session on Democracy I spoke at in London last November. As I wrote to him after watching some of his presentations on his book:

I can’t think of anyone I know who’s managed to rise to the top of newspaper commentary, to change his views of the world in ways that can be uncomfortable with his readers and yet still to retain their deep respect. It’s a great achievement, and also the product of great effort. Here you are with a substantial book which you’ve written while keeping your day job and you’re throwing yourself into it to do what you can to save us from the abyss. … I don’t know about the UK, but there’s not a single figure in Australian public life who’s managed to fly so high without flattering the Great and the Good.

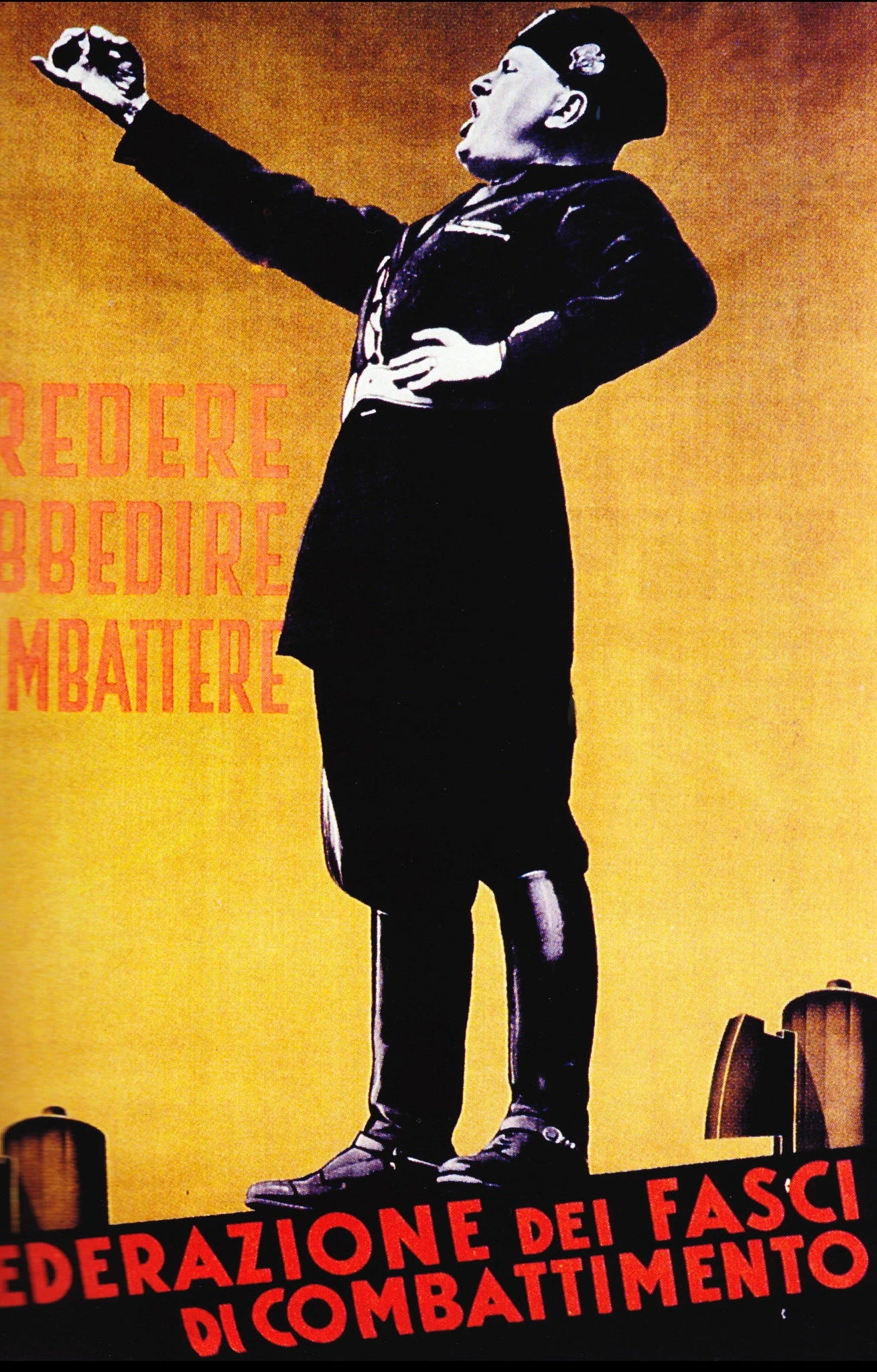

I also wanted to add my two cents worth on fascism. Fascism is often spoken of as if it’s a political doctrine. But it’s also a practice. And I think its most distinctive aspect is an endorsement of lawlessness and violence by the people in the people’s name. This was true of fascism in Germany, Italy and England in the 1930s. And Trump encourages violence. In many ways it’s a tribute to the law-abiding nature of Americans — including many far-right crazies — that the kind of low level constant terrorism that was alive and well in the South from before the civil war until a decade or two after civil rights has not yet taken hold, despite winks and nods of encouragement from Trump. Anyway, over to Martin:

Umberto Eco describes a number of characteristics of “Ur-Fascism — or Eternal Fascism”. One feature is the cult of tradition. Fascists worship the past. The corollary is that they reject the modern. “The Enlightenment, the Age of Reason,” Eco writes, “is seen as the beginning of modern depravity. In this sense Ur-Fascism can be defined as irrationalism.”

Another feature is the cult of action for action’s sake, from which flows a further one: hostility to analytical criticism. And it follows from this that “Ur-Fascism . . . seeks for consensus by exploiting and exacerbating the natural fear of difference . . . Thus Ur-Fascism is racist by definition.”

Another aspect is that “Ur-Fascism derives from individual or social frustration. That is why one of the most typical features of the historical fascism was the appeal to a frustrated middle class.” Ur-Fascism binds the supporters it recruits from the ranks of the disaffected middle class through nationalism. Those followers, Eco adds, “must feel humiliated by the ostentatious wealth and force of their enemies”.

For Ur-Fascism, moreover, “there is no struggle for life but, rather, life is lived for struggle”. Next, for Eco, is the fact that Ur-Fascism advocates a popular elitism. In Ur-Fascism, he writes, “Every citizen belongs to the best people of the world.” Moreover, “everybody is educated to become a hero”.

For Ur-Fascism, Eco adds, “the People is conceived as a . . . monolithic entity expressing the Common Will. Since no large quantity of human beings can have a common will, the Leader pretends to be their interpreter.”

The origin of Ur-Fascism’s distinctive machismo is that “the Ur-Fascist transfers his will to power to sexual matters”. Implied here is both disdain for women and intolerance and condemnation of non-standard sexual habits.

Finally, “Ur-Fascism speaks Newspeak” — it lies systematically. As Hannah Arendt noted in an interview in the New York Review of Books in 1978, “If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer.” The followers believe the leader, simply because he wears the sacred mantle of leadership.

This is a fascinating list. If one looks at today’s rightwing populism, one notices precisely the cults of the past and of tradition, hostility to any form of criticism, fear of differences and racism, the origins in social frustration, nationalism and fervent belief in plots, the view that the “people” are an elite, the role of the leader in telling his followers what is true, the will to power and the machismo. …

The fascism of Germany or Italy of the 1920s and 1930s does not now exist, except perhaps in Russia. But the same could be said of other traditions. Conservatism is not what it was a century ago, as is true of liberalism and socialism. … History does not repeat itself. But it rhymes. It is rhyming now. Do not be complacent. It is dangerous to take a ride on fascism.

Brexit: the disaster in detail

I only watched snippets of this, but had to exercise some discipline to do other stuff I decided was a higher priority. But from what I saw, I recommend the film if you have time. Brexit is reminding me of shock therapy in post-communist Europe. A thoroughgoing transformation brought about by an absurdly simplistic and ideological understanding of how the world is put together. The film’s endless examples show something I argued in this column years ago.

Policy discussion typically conceives of markets as comprising competitive firms subject to state regulation. In areas like education, health, aged care, city planning, research and legal services, output is better thought of as the joint product of competitive and collective (collaborative and regulatory) activity. Each sector requires the evolution of quite different institutions in which public and private, competitive and collaborative considerations concatenate at every level from high policy down to the life-world of workplaces.

Those points were made presuming we were only considering one jurisdiction. Mutatis mutandis they apply with a vengeance when considering nearly thirty jurisdictions.

The world’s coolest dictator

Your ignoramus correspondent knew nothing of this. But he does now.

President Nayib Bukele, who has just won re-election in a landslide, the country has shifted from a functional multiparty democracy "to a de facto one-party state". In his first term, he packed the constitutional court with loyalists, thereby managing to sidestep a ban on presidents seeking consecutive terms. And, last week, he duly triumphed again at the polls, winning 87% of the vote for himself as president, while his Nuevas Ideas party won control of the national legislature. His astonishing popularity hinges on one thing only: his sweeping crackdown on El Salvador's gangs and cartels. …

With his "sunglasses and leather jacket", Bukele once jokingly styled himself on X/Twitter as "the world's coolest dictator", said Carmen Quintela in El Diario (Madrid), though now he calls himself "philosopher king". … At 34, he was elected mayor of San Salvador on an FMLN ticket, vowing to reclaim dangerous areas from gangs, but was expelled from the party and set up his own. And it was on an anti-crime agenda that he was first elected president in 2019.…

His success has been extraordinary. … In 2018, the homicide rate was 51 per 100,000 people: last year it was just 2.4 per 100,000 (about half the level of the US); shops no longer have to pay protection money; people can leave their homes without fear. None of that has been achieved by some miracle of good governance, said Catherine Ellis on Al Jazeera (Doha): it's the result of a truly draconian clampdown on civil liberties. Bukele has let police arrest anyone they suspect of gang links. … Those arrested, seldom given a proper trial, are housed in El Salvador's hideous 40,000-capacity "mega jail". Their heads are shaved, their hands and feet shackled, and they never see daylight. Bukele's crackdown might be popular, but it's astonishingly inhumane.

Nor have Bukele's policies – including his eccentric decision in 2021 to make bitcoin legal tender – done anything to improve the economy, said Julia Gavarrete in El Faro (San Salvador). El Salvador is still one of Central America's weakest economies; much of its 6.5 million-strong population can't afford basic staples.…

But … a Bukele-style crackdown is unlikely to work elsewhere. Unlike the big cartels in other Latin American countries, Salvadoran gangs – poorly financed and less well armed – have never been big players in the drugs trade: their focus has been extortion. When Bukele arrested their foot soldiers, they collapsed. That won't happen in places such as Mexico, Colombia and Brazil. Latin American leaders might envy Bukele for his popularity, but they face a chaotic battle with their own gangs if they try to take them on – and will do "lasting damage to democracy" in the process.

Ralph Balson

I never took much notice of Ralph Balson until one day — many years ago — I went to a retrospective exhibition of his paintings. They’re lovely.

Nothing succeeds like success (But narcissism helps)

From “Science, narcissism and the quest for visibility” by Bruno Lemaitre

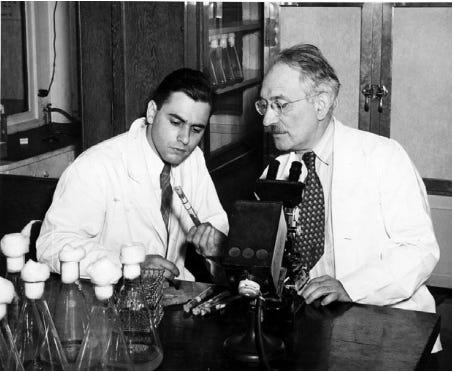

The importance of visibility for recognition. The discovery of the antituberculosis antibiotic streptomycin was mostly the endeavour of student Albert Schatz (left) working day and night in the basement of the laboratory of professor Selman Waksman (right) at Rutgers University (USA). While both of them co-signed the first publication and the patent, by increasing his visibility, Waksman appeared to be the only discoverer. Waksman travelled around the world to present his discovery of streptomycin, portraying himself as a generous and modest benefactor of humanity, which resulted in him being seen as the sole discoverer of the drug. When the contribution of his student Schatz was recognised a few decades later, Schatz conceded to a journalist that his main surprise was that nobody had ever asked him how the discovery of streptomycin was really made. The scientific community was interested in the spectacle with the figure of the great savant, not the reality in the laboratory.

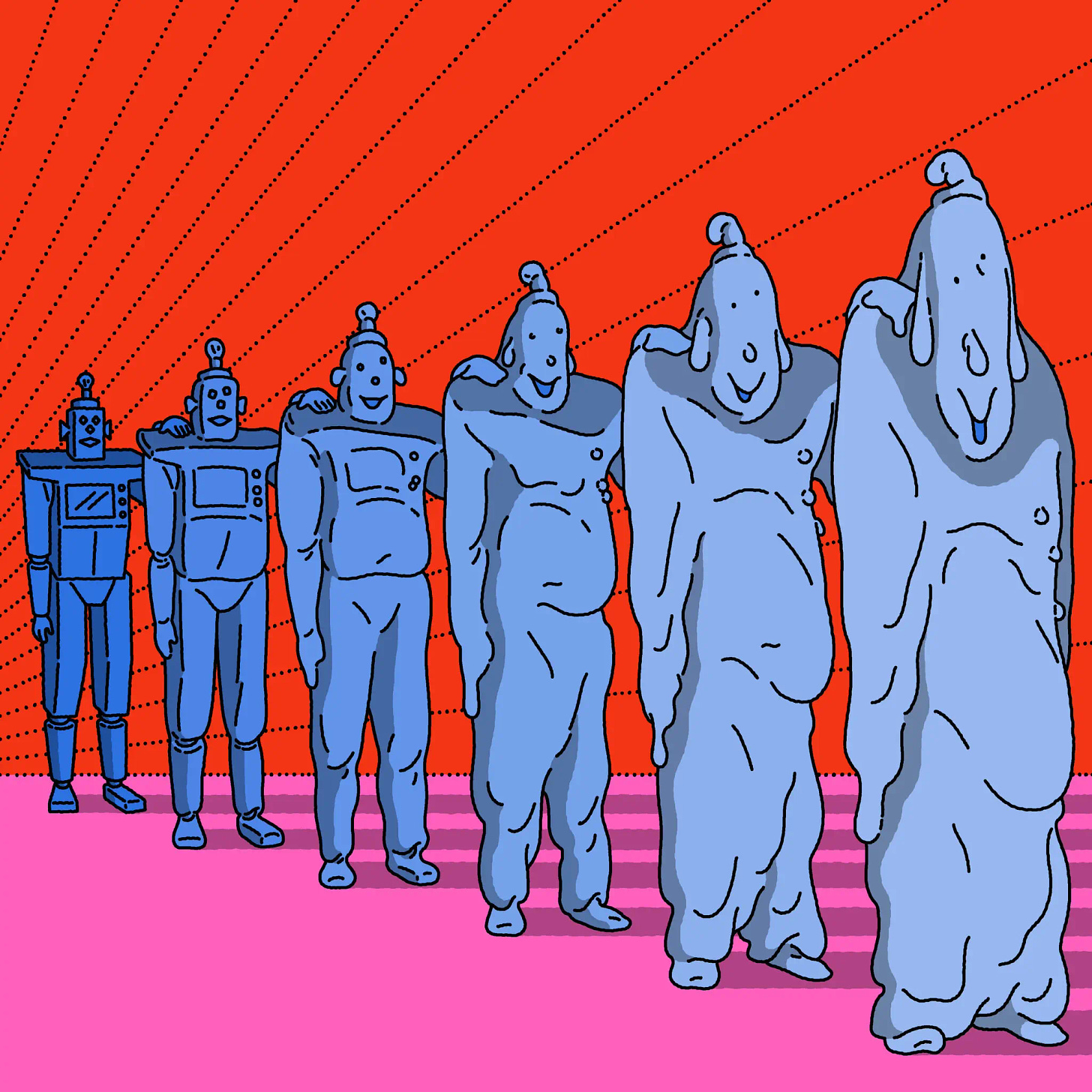

The cultural threat of AI

Whether or not AI is an existential threat to our species physical existence, only a couple of years from its prime time arrival it’s already clear how devastating reducing the marginal cost of bullshit to zero will be. Eric Hoel takes up the story and makes a proposal. It won’t go anywhere I fear. But then I would have said the same about same sex marriage. Still they’re different issues and this one requires some intellectual consensus and some interest from the demos on something which looks harmless enough on its surface and is fairly abstract. In fact I expect in a few years his idea of watermarking AI output will look quaint just because the melding of I and AI will be so ubiquitious. Anyway, here’s hoping I’m wrong.

Increasingly, mounds of synthetic A.I.-generated outputs drift across our feeds and our searches. The stakes go far beyond what’s on our screens. The entire culture is becoming affected by A.I.’s runoff, an insidious creep into our most important institutions.

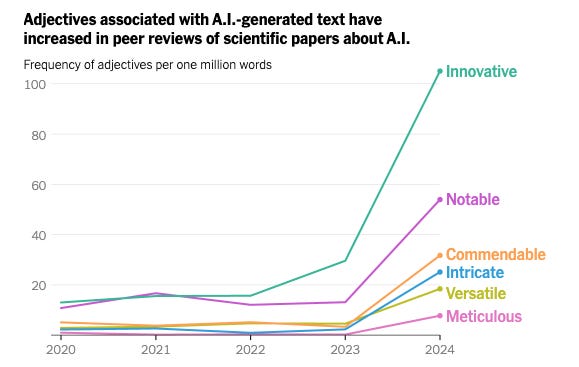

Consider science. Right after the blockbuster release of GPT-4, the latest artificial intelligence model from OpenAI and one of the most advanced in existence, the language of scientific research began to mutate. Especially within the field of A.I. itself.

What’s going on in science is a microcosm of a much bigger problem. Post on social media? Any viral post on X now almost certainly includes A.I.-generated replies, from summaries of the original post to reactions written in ChatGPT’s bland Wikipedia-voice, all to farm for follows. Instagram is filling up with A.I.-generated models, Spotify with A.I.-generated songs. Publish a book? Soon after, on Amazon there will often appear A.I.-generated “workbooks” for sale that supposedly accompany your book (which are incorrect in their content; I know because this happened to me).

To deal with this corporate refusal to act we need the equivalent of a Clean Air Act: a Clean Internet Act. Perhaps the simplest solution would be to legislatively force advanced watermarking intrinsic to generated outputs, like patterns not easily removable. Just as the 20th century required extensive interventions to protect the shared environment, the 21st century is going to require extensive interventions to protect a different, but equally critical, common resource, one we haven’t noticed up until now since it was never under threat: our shared human culture.

In memory of the brave folks fighting to keep Australia safe from Socialism

The political threat of AI

A year ago—20 months before the coming presidential election—two AI researchers published a paper that looked at ways AI might shift “the balance of persuasive power.” They said that “increasingly anthropomorphic AI systems” could “allow personalized persuasion to be deployed at scale,” bringing newly powerful disinformation campaigns and other bad things.

The logic is straightforward. Traditionally, deploying an army of online influencers has cost real money, since “keyboard warriors” don’t work for free. With the advent of large language models, you can deploy thousands and thousands (and thousands, and so on…) of sophisticated chatbots that do work for free.

Last week researchers at two European universities provided evidence that the problem is even worse than that. Their study found that LLM-based chatbots, in addition to being cheap and verbally fluent, are better than humans at persuading humans—and better in a particularly ominous way.

The researchers, from Switzerland’s École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne and Italy’s Fondazione Bruno Kessler, recruited 820 humans and one chatbot (ChatGPT-4) and placed them in short, structured online debates. Half of the debates were human-on-human and half were human-on-bot. Before the debates, the humans were asked for their views on a given issue (abortion, death penalty, arming Ukraine, etc.). Then they were randomly assigned to defend one side of the issue. They then debated a person or a bot (they weren’t told which), and afterwards they were asked again about their views on the issue.

In the bare bones version of the experiment, the bots were only slightly better than humans at moving their debate opponents toward their position; the difference wasn’t big enough to pass the test for statistical significance. But when bots were given demographic data about their debate opponents, they got much better at changing minds. Humans, given the same data about their opponents, got slightly worse at persuasion. The authors write, “Not only are LLMs able to effectively exploit personal information to tailor their arguments, but they succeed in doing so far more effectively than humans.”

Freddie Deboer on Adele Waldman

I’m proud to say I checked out Adele Walman’s The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P, before the rave reviews came, but that was through no genius in spotting such things of my own, though perhaps it reflected good taste in friends. Or their sisters. She’s the sister of econoblogger of great note Steve Randy Waldman of Interfluidity and a friend of mine. (Note to self: I should keep a closer eye on the blog so I can show my readers one of his posts). Anyway, she’s just written a new novel. However I thought Freddie’s summary of the first novel was so good, I’ve extracted that, and his conclusion about the new book.

The novelist Adelle Waldman has lately been in a situation that other writers both envy and fear: she’s released a long-awaited follow-up to a remarkably successful first novel, … a story about literary types living in Brooklyn that earned the love of both that type of person and the type of person who loves to hate them. The book’s great accomplishment was an exquisitely tuned sense of authorial judgment, one which frequently lampooned the pretension and lack of self-knowledge of its self-important characters while never seeming to take the easy way out by making caricatures of them. Protagonist Nate Piven, the titular Nathaniel P., is possessed of an infuriating and remarkably true-to-life combination of outsized self-regard and perpetual insecurity. His burgeoning success as a writer makes him enviable to his peers, many of whom are chasing the same kind of success, and yet every step he takes up the ladder leaves him more consumed with the feelings of inadequacy that he’s working hard to scrub from his persona. Nate gets himself into a series of awkward situations, thanks to the titular love affairs, his elevated ambitions, and the various petty jealousies of his peers. Like any comedy of manners, The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. succeeded as well as it did - it was both a critical smash and sold very well for a literary novel - because it was both a portrait of a very specific time but also timeless. The novel was a reflection of a small, self-obsessed slice of humanity; the NYT review stressed how Nate cut a familiar figure. Yet you leave the novel understanding that its characters were simply playing the same games people of that age have always played.

And, yes, Nate and his peers are subject to some pretty blistering satire, much of it owing to Nate’s inability to process anyone else’s feelings without running them through the filter of his own. Yet the digs never feel personal. To make a weird comparison, Waldman’s narrative perspective in Nathaniel P. reminds me of Freud writing about his patients: there are all the parts common to judging, but there is no judgment, only clinical observation.

If that all sounds Discourse-y, you’re right! I’m sure there’s already readers scrambling to the comments to say that this all sounds insufferable. (The Goodreads reviews for the book are a shambles.) Nathaniel P. generated a mountain of coverage for two dovetailing reasons: it described a kind of person that many people love to hate while inspiring feelings of queasy self-identification among people who would like to think they could never be a Nate P. In a typical scene, he’s either doing something that’s unlikable or demonstrating the kind of self-consciousness about status and appearance that many of us find viscerally annoying even when not doing anything else wrong. Nate has hit upon recent success as a writer that has made him more desirable in the sexual marketplace of literary Brooklyn, and while he’s not a predator, he’s also all too aware of his newfound powers. … [W]hile Nathan is frequently irritating, and a number of his relationships are insincere and transactional, and I’m glad he’s not dating my sister, he’s never sinister. He just doesn’t know how to pursue what he wants romantically and sexually after being socialized into a world where feminist norms have taught him more about what he must not do than what he should do. …

I am far from the first to note that Waldman could have easily just come back, after ten years, with the same kind of novel as her first, with Even More Love Affairs of Nathaniel P., another look at the mores of characters who are upper-class in their tastes and education if not in their bank accounts. Maybe this time it would have been aspiring filmmakers in Silver Lake or ambitious academics in Princeton. That book wouldn’t have sold as well as its predecessor, the New Yorker might have relegated it to the Honorable Mentions section of its annual best book list, but it would have been safe and would have sold well enough to earn a big advance on her next book and maybe somebody would have gotten a movie made out of it this time. It’s clear that, after the runaway success of The Loves of Nathaniel P., she wanted to write characters that were not like her, characters whose lives were not like hers. In ways both comfortable and not, she’s succeeded.

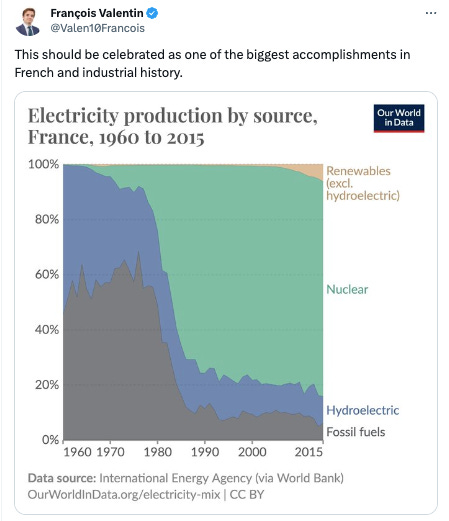

Nuclear sure helped one country with the climate transition

Yuval Noah Hirari on Israel

Well worth listening to Harari’s view of Israel today.

Est

I recall back in the 1980s, a fellow worker in Parliament House telling me they’d gone on this crash course of self-discovery that was really powerful. It sounded powerful enough — and also like a cult. I think she told a story of some confrontation and people ‘got it’ and healed their relationships and on and on. For a week or so, after which things went back to normal. That was Est for me. Anyway, you could have knocked me over with a feather when I saw that William Bartley III a fairly substantial scholar of Popper and Hayek had written a book about Werner Hans Erhard, the person who cooked up Est.

When I looked at Wikipedia it didn’t improve. Born John Paul Rosenberg, Werner Hans Erhard assumed a false identity with his lover and deserted his wife! Anyway, Bartley got interested because Est had cured his decades-long insomnia, which had been impervious to both psycho and pharmaco therapies. Anyway, Est is no more, and I doubt I’ll go further down this rabbit hole, but as part of my services to open-mindedness I reproduce for you the rather intriguing section of a book on cults which covers it. Its cultish method is there to see — but it’s pretty impressive that so many folks think well of it several months after the sessions and that that goes for professional therapists did the course also.

In the Secular Mainstream: est

For another view of the role of altered consciousness in promoting member- ship in a charismatic group, we might ask how a contemporary population can be made susceptible to such influence when the right social setting is established. Consider an "experimental" problem in the psychology of the charismatic group: How might one engage a population of sophisticated, well- educated adults from metropolitan centers in a new, zealously espoused ide- ology, where the techniques employed can include the development of a co- hesive group setting and the promotion of attitude change via altering consciousness? One answer comes from the example of est, an acronym for Erhard Seminars Training.

This secular movement was started in 1971 by Werner Erhard, a man with no formal experience in mental health, self-help, or religious revivalism, but a background in retail sales. Within only five years of its founding, est had reportedly put over 83,000 generally affluent and well-educated people through its training, aimed at "transformingyour ability to experience living." Erhard and his trainers combined aspects of a number of popular philoso- phies, from Eastern religion to psychoanalysis, in a program that would sup- posedly make participants appreciate the need to confront their own conflicts and social circumstances and dismiss long-standing illusions.

The training program consists of two weekend-long workshops with evening sessions on the intervening weekdays. Workshops with about two hundred enrollees are led by a trainer designated by Erhard and several experienced assistants. Over the course of nine days, enrollees are cajoled and emotionally battered, and encouraged to regress up to the point where they have finally "got it," a state akin to a conversion.

Certain alterations in consciousness and subjective state within this large group context are apparently used to promote this conversion-like experience. Workshop members are subjected to a variety of unsettling circumstances for long hours at a stretch that act to peel away those layers of psychological stability that normally bolster their usual state of consciousness. Several in- junctions are issued: no watches, no talking unless recognized by the trainer (which means rarely), no leaving one's seat, no smoking, no eating, no going to the bathroom except during breaks separated by many hours. Participants undergo long periods during which they must keep their eyes closed and listen to diatribes, abuse, and obscenity dispensed by the trainer. They are also generally kept in rooms where there is no daylight, at temperatures that may become uncomfortable (such as 40°). In addition, they are usually exposed to a number of individuals within the group who respond with intense emotion, crying copiously or screaming. A variety of physiologic and emotional para- meters are therefore disturbed, disrupting the enrollees' homeostasis. Partic- ipating in the program is not without psychiatric risk, and a number of cases of psychotic reaction have been reported among those enrolled.33

What it means to "get it" in est is hard to define. After an initial corre- spondence with Werner Erhard, I met at some length with the movement's director of research so that we might consider studying this transformation. Our discussions of getting it, however, yielded no operational definition (or any viable basis for a study, for that matter).34 One account of the attitude of an est trainer may be helpful in defining this observation further. Just before graduation, the trainer always asks if people "got it." Some say yes and are applauded. Another group isn't sure. The trainer talks to them and they all say they got it. Finally, one or two people are sure that they haven't got it, and the trainer says, "Well, you got it, because there's nothing to get." The whole thing is treated as a joke, discomforting the new converts.35 Nonethe- less, one study of a large sample of est alumni who had completed the training at least three months before revealed that the large majority felt the experience had been positive (88%), and considered themselves better off for having taken the training (80%).

Psychological sophistication does not seem to breed skepticism among those exposed to the program. In the study of est alumni, for example, there was no significant difference in the proportion of professional therapists or lay-people who gave positive reports. In another study, an experienced clinician evaluated a series of his psychiatric patients who took the est training and concluded that the majority derived some benefit from the program.

One psychologist who had been through the training told me of his distress at the psychological assaults against some of the more labile workshop mem- bers, but his words also revealed the role of altered consciousness in over- coming these apprehensions.

The physical discomfort and badgering left me horrified, and feeling very weird. Time had stopped running in any usual sense, and I was having unexpected feelings of all kinds. At one point, when the trainer called my friend an asshole for trying to console a woman who was crying, I got enraged; I wanted to see the trainer dead. I realized that I was be- ginning to lose any sense of where I was in the real world, and even who I usually was.

And then suddenly it came clear! I was the prisoner of my own com- pulsion to help everyone and be kind to them. The trainer was right; I didn't have to be tied down by this attitude. I was free to choose what I might think and feel, independent of forty years of programming. Then the whole room seemed to slip away, and I no longer cared about eating, peeing, or how long the whole damn thing would run on. I felt liberated, released from a long prison term.

In one sense, this represented a transition to a full-blown "culture of narcissism" in which the individual owes allegiance only to the self. Participants in the est program often feel released from the commitments born out of fidelity to their fellow humans, allowing them to indulge themselves without guilt. In another sense, however, est underlines how much we each act on our own set of comfortable misconceptions. Whether or not the realization of this psychologist ultimately proves useful to him, it did indeed come after his feeling and thought had been altered from their usual state.

From Cults, Faith Healing and Coercion

McKinsey: never met a drainpipe it couldn’t send a rat up

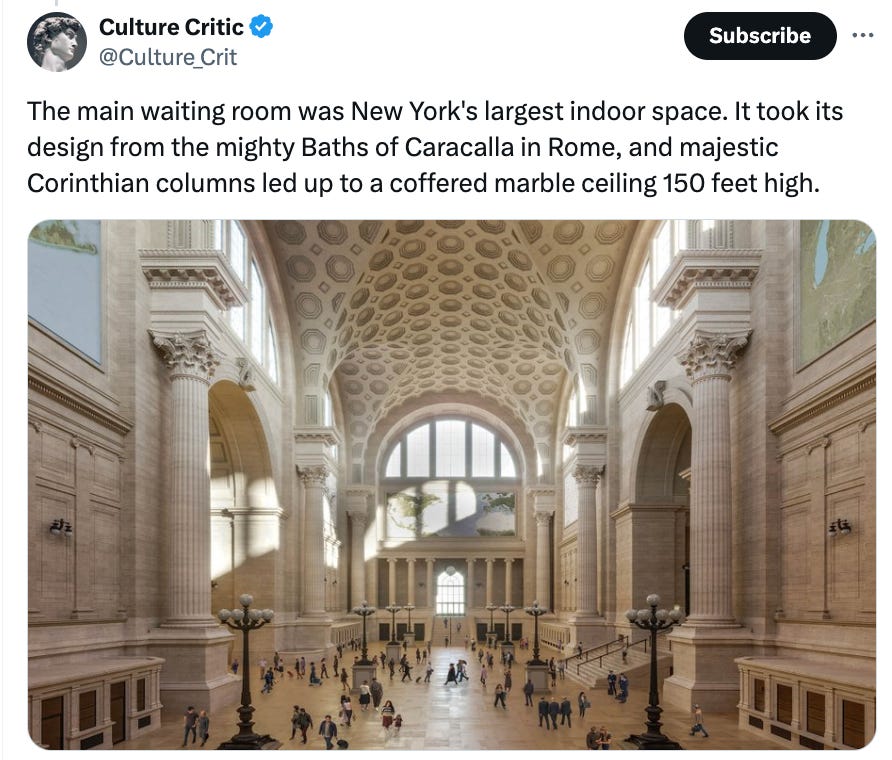

Penn Station NYC: demolished to make way for Madison Square Garden

Heaviosity half hour

Hannah Arendt on means, ends and utilitarianism

From Chapter 21 of The Human Condition.

INSTRUMENTALITY AND Homo Faber

The implements and tools of homo faber, from which the most fundamental experience of instrumentality arises, determine all work and fabrication. Here it is indeed true that the end justifies the means; it does more, it produces and organizes them. The end justifies the violence done to nature to win the material, as the wood justifies killing the tree and the table justifies destroying the wood. Because of the end product, tools are designed and implements invented, and the same end product organizes the work process itself, decides about the needed specialists, the measure of co-operation, the number of assistants, etc. During the work process, everything is judged in terms of suitability and usefulness for the desired end, and for nothing else.

The same standards of means and end apply to the product itself. Though it is an end with respect to the means by which it was produced and is the end of the fabrication process, it never becomes, so to speak, an end in itself, at least not as long as it remains an object for use. The chair which is the end of carpentering can show its usefulness only by again becoming a means, either as a thing whose durability permits its use as a means for comfortable living or as a means of exchange. The trouble with the utility standard inherent in the very activity of fabrication is that the relationship between means and end on which it relies is very much like a chain whose every end can serve again as a means in some other context. In other words, in a strictly utilitarian world, all ends are bound to be of short duration and to be transformed into means for some further ends.19

This perplexity, inherent in all consistent utilitarianism, the philosophy of homo faber par excellence, can be diagnosed theoretically as an innate incapacity to understand the distinction between utility and meaningfulness, which we express linguistically by distinguishing between “in order to” and “for the sake of.” Thus the ideal of usefulness permeating a society of craftsmen—like the ideal of comfort in a society of laborers or the ideal of acquisition ruling commercial societies—is actually no longer a matter of utility but of meaning. It is “for the sake of” usefulness in general that homo faber judges and does everything in terms of “in order to.” The ideal of usefulness itself, like the ideals of other societies, can no longer be conceived as something needed in order to have something else; it simply defies questioning about its own use. Obviously there is no answer to the question which Lessing once put to the utilitarian philosophers of his time: “And what is the use of use?” The perplexity of utilitarianism is that it gets caught in the unending chain of means and ends without ever arriving at some principle which could justify the category of means and end, that is, of utility itself. The “in order to” has become the content of the “for the sake of”; in other words, utility established as meaning.

European Jewish intellectuals and Israel

Readers who get down as far as Heaviosity Half Hour know that I’m writing some stuff on Karl Popper in the process of writing about Michael Polanyi. And I’m also interested in Raymond Aron, probably the most prominent post war French intellectual who wasn’t a Marxist. (He was also comprehensible, which seems to be a substantial achievement for a French intellectual).

Here’s the biographer of Karl Popper

Paradoxically, the ethnonational principle triumphed just as the European nation-state lost its autonomy. The Cold War liberals were among the first to recognize that, with the rise of the United States and the Soviet Union as superpowers, the European nation-states had lost their sovereignty over foreign policy and required global alliances for their defense. They urged their compatriots to reconcile them- selves to the “age of empires,” but they continued to think of these empires as composed of nation-states. Central and Eastern Europe had just been ethnically cleansed along nation-state boundaries, so alternative polities seemed utopian. Multicultural empires, multiethnic nation-states, and cosmopolitan diasporas belonged to Europe’s past and future. They were beyond the horizon of even the most as- tute observers of postwar Europe.

Raymond Aron and the Dilemmas of Jewish Assimilation in the Nation-State

Raymond Aron was such an observer. A political sociologist, journal ist, and professor at the Sorbonne, he was the undisputed leader of the small French liberal intelligentsia, a minority in danger of being overwhelmed by the intellectual hegemony of the left. An avowed Atlanticist and an internationally respected political analyst, he was also a French patriot, providing a model of negotiating national and in- ternational commitments. More tentative and self-reflective about his Jewish identity than most Cold War liberals, Aron’s evolving reflections on Jewish assimilation, the Jewish diaspora, and Israel chart the dilemmas of the nation-state and of Cold War liberalism and reveal the intractability of the Jewish Question.

The powerful French melting pot ensured that citizenship, though politically defined, would carry the heavy imprint of a national culture, effacing regional and ethnic differences. Nineteenth-century French Jews, enthusiastic about citizenship, willingly bid farewell to traditional Jewish culture. Until the post–World War II years, they constituted the most severe testing site for national integration, as challenges to the Third Republic tended to repeatedly center on them. As Aron was growing up, however, the Republic emerged triumphant from the Dreyfus Affair, the ideals of 1789 vindicated. A highly acculturated, often assimilated Jewish academic elite led the charge in developing a Republican civic religion—secular, patriotic, yet universalist—a state ideology that served also to integrate the Jews and make good on the promise of emancipation. This represented a stark contrast to the contemporary German academy and state and to the travails of emancipation in Central Europe.

Aron’s highly acculturated family had few ties to the religious com- munity. He learned that he was Jewish through an insult suffered from a classmate in school. At the prestigious Lycée Condorcet and École Normale Supérieure, preparatory schools for the French administrative and educational elite, Jewish and non-Jewish students intermingled. At the Sorbonne of the 1930s, most of Aron’s mentors, from Léon Brunschwicg to Élie Halévy, were of Jewish origin. The encounter with German antisemitism during Aron’s sojourn in Germany in the early 1930s shocked him. Back at home, the Action Française and its like were determined to undermine the polity that made Léon Blum’s Pop- ular Front government possible. But Aron called for mobilization against Nazi Germany as a French patriot, consciously keeping away from Jewish issues, lest his impartiality be questioned. His silence on antisemitism continued into World War II when, as an editor of La France libré, the organ of Charles de Gaulle’s government-in-exile in London, he downplayed the Vichy government’s anti-Jewish policies and was more forgiving of its collaboration with the Nazis than those around him. The Holocaust, he explained later, was unimaginable, a watershed in Jewish history. Until World War II, one could assume that assimilation would progressively solve the Jewish Question and act accordingly, deemphasizing Jewish difference. One could no longer think so in the aftermath of the Holocaust. The memory of those who had perished ruled out assimilation, normatively or practically. In 1951, he told a Bnai Brith audience that a residual difference, be it religious or cultural, would always remain between the majority of the French and the Jews. The nation-state had to respect this difference. Neither the Holocaust nor the newly established State of Israel figured prominently in his work in the first decade after the war, but both changed his disposition toward being Jewish in ways that often became pronounced later in life. He was initially unenthusiastic about the Jewish state, thinking it would never live in peace in the Middle East, but it grew on him. His repeated visits to Israel, beginning in 1956, his admiration for its accomplishments, and his sympathy with the Israeli narrative of the Middle Eastern conflict testify to a growing solidarity. This did not mean abnegation of his critical faculties: his analyses of the Middle Eastern situation remained dispassionate, and he thought the 1956 Suez War an irresponsible adventure.

Israel represented a new alternative—secular Jewish national life. Aron repeatedly queried the implications of the diaspora for the Jews’ relationship with Israel. Contrary to Zionist narratives, he saw no teleology in Jewish history leading to Zionism. The connections tying Jews together were ephemeral: religious practice in divergent communities, each shaped largely by its social context. There was no ethnic continuity between the ancient Israelites and contemporary Jews. Even conceding that restrictions imposed by hostile religious majorities had shaped essential Jewish traits over the centuries, the European nation-states prior to the Holocaust were quickly assimilating their Jews. They created the “de-Judaized Jew” ( Juif déjudaïzé, as Aron kept referring to himself, articulating the difficulty of defining the highly acculturated Jew). What could possibly tie a de-Judaized Jew to Israel and the Jewish people? When pressed, Aron presented ethical universalism as his Jewish legacy, but philosophically, he said, he felt closer to Christianity than Judaism. Sympathetic though he was to Israel, his foremost commitment was to France; he was a for- eign visitor when in Jerusalem. Jews who felt otherwise, Aron believed, would do well to immigrate to Israel.

The 1967 Middle Eastern War and its aftermath upset the delicate balance in Aron’s life between sympathy for Israel and French patrio- tism and drove him to greater engagement with Jewish issues. In the days preceding the war, he appended urgent and uncharacteristically emotional notes to his astute critiques of the failure of the United Nations and the Great Powers to contain the regional conflict. They suggested that, were the Jewish state to be vanquished, his life and those of many Jews would lose their meaning. General de Gaulle’s notorious November 1967 press conference, where he resurrected antisemitic stereotypes of Jews (“an elite people, sure of itself and domineering”) to explain Israeli policies, deeply disturbed Aron. He argued against the general’s antisemitic essentialism just as he had argued against Zionist essentialism, but the general, he feared, had opened the floodgate to an antisemitic wave. In future years, Aron would be on the alert for any resurgence of French antisemitism. Gone was his earlier apprehension that Jews themselves could not fight antisemitism, that it was a French problem, for non-Jews to handle. His De Gaulle, Isräel et les juifs led the charge. He now openly demanded that France accept the sympathy of Jews for Israel, even when it conflicted with French foreign policy.

The problem of “dual loyalty” led him in the 1970s to interesting, if preliminary, reflections on the limits of the nation-state. The ad- vent of both globalization and the European Economic Community raised the prospect of “multinational citizenship.” Aron remained de- cidedly skeptical about the possibility of such citizenship, insisting that, however integrated the European economies may have become, the nation-state must remain the locus of sovereignty and military service. But he did suggest, emphatically, that ethnic and linguistic pluralism was compatible with national unity. Until then, he had never questioned the French melting pot, the enforced uniformity of liberal nationalism. Now he came out against national uniformity that would make transnational affinities impossible. Moreover, argu- ing against Arnold Toynbee’s vision of the Jews as a historical fossil, a relic of antiquity, he gave a nod to Toynbee’s conception of the Jewish diaspora as presaging the future order of humankind. But he never pursued these ideas and remained unsympathetic to “multicultural- ism,” unwilling to compromise the French national ethos. At every opportunity, he volunteered that he was not a Zionist. The Jewish Question cracked the national monolith, but Aron could conceive of no alternative.

Acknowledging he was “a Jew whom a semi-free French govern- ment [i.e., Vichy] had excluded from his country through a statute based on racial criteria,” Aron remained a French patriot. He felt uncomfortable with the radical revision of Vichy’s history under way in the 1970s, which implicated France in the Holocaust. He sought to retain a more traditional narrative, highlighting France’s struggle with fascism. His last public statement was a testimony on behalf of a friend, Bertrand de Jouvenel, in a libel suit he brought against Israeli historian Zeev Sternhell. The latter argued that interwar France had been saturated with fascist ideas, culminating in Vichy, and implicated De Jouvenel as a collaborator. During the final months of his life, Aron was wavering between acceptance and rejection of the new vision of interwar France. His testimony in the trial signaled that he was not willing to give up on the France of his youth. The tensions between French patriotism and sympathy for Israel, French nationalism and Jewish identity, liberal pluralism and national uniformity, French interests and the European and trans-Atlantic communities permeated his life to the end. Asked in 1983 about the source of his attachment to Jewish identity, Aron conceded: “I myself do not know. . . . It is . . . an existential choice. I cannot say more.”

Karl Popper and the Antinomies of Cosmopolitanism and Anti-Zionism

Karl Popper had little tolerance for Zionist or any nationalist dilemmas. He was among the few Cold War liberals who carried the torch of radical cosmopolitanism passed over from the interwar Central European Jewish intelligentsia. A vehement anti-Zionist, a trenchant critic of nationalism, and a cosmopolitan who pleaded the cause of progressive empire, Popper, an eminent philosopher of science and politics, was a rare bird among the Cold War liberals. Born, raised, and buried in Vienna, he immigrated to New Zealand early in 1937 and spent World War II there. He settled in England in 1946 and lived most of the second half of his life near London, admired and respected but without ever quite finding his place in the British academy or society.

The social and intellectual milieu of the assimilated Viennese Jews shaped Popper’s philosophy, and their dilemmas of national identity informed his cosmopolitanism. Striving for recognition as German Austrians, the progressive Jewish intelligentsia sought to strip religion and ethnicity of significance—their own, first and foremost. Being German was a matter of culture, not race. They represented a group that, to emancipate itself from its own ethnicity, needed to dissolve all ethnicity and claim universal humanity. Like them, Popper advocated Jewish assimilation into German culture, but, unlike them, he decried German nationalism and held it responsible for the disintegration of the Habsburg Empire. His cosmopolitanism was radical.

The principle of national self-determination, he argued, was responsible for the catastrophes of modern European history, for the dissolution of multicultural and multiethnic empires, for ethnic cleansing and murder. It destroyed the blissful world of his childhood, shattered Central European culture, and sent him into permanent exile. He was not going to sanction national self-determination for the Jews. Indeed, they needed to be the first to give it up.

To Popper, nationalism was fraudulent, an invention of reactionary German intellectuals from Herder to Fichte to Hegel. Already in 1927, as a young socialist in Vienna, he made short shrift of the concept of Heimat. Writing The Open Society during World War II, he developed a formidable critique of the nation-state. “The idea that there exist natural units like nations or linguistic or racial groups is entirely fictitious,” he said. “None of the theories, which maintain that a nation is united by common origin, or a common language, or a common history, is acceptable, or applicable in practice. The principle of the national state . . . is a myth.”

Central European conceptions of nationality and imperialism shaped Popper’s views. Imperial Austria made ethnicity (Volksstamm, also tribe or race) the basis of claims for nationality (Nationalität) and cultural autonomy. Popper decried “tribal nationalism” or, in current parlance, ethnonationalism. The French Revolution’s political definition of the nation was the only one he accepted, but he emphasized that any nation must abide by international law. He had no sympathy for the French “melting pot,” which suppressed minorities and dialects to create homogenous populations. He celebrated universal humanity, not multicultural diversity, but assimilation’s virtue, as he saw it, was that it provoked a “culture clash,” not that it produced national uniformity. Czech and Jewish immigrants in Vienna who had to study German faced a cultural dissonance conducive to creativity. “Culture clash” should not, however, become territorial. National borders were conventional, and nationalist claims to set “natural borders” were groundless and dangerous. To forestall ethnonational madness, one had to accept the status quo and arm an international force to protect it.

Popper’s antidote to nationalism was imperialism, which, he thought, promoted the unity of humankind. Western history was a continuous struggle between progressive imperialism and reactionary nationalism. “From Alexander onward, all the civilized states of Europe and Asia were empires, embracing populations of infinitely mixed origin.” Like other Central European émigrés to England, he regarded the British Commonwealth as the largest free community on earth. It extended hospitality to him in England and provided a wartime refuge in New Zealand. As he was writing The Open Society, German totalitarianism and British democracy were at war. If the democratic cosmopolitan empire survived, nationalism may subside and enlightenment may spread. The progressive empire, an “Open Society,” represented the last metamorphosis of the multinational Habsburg ideal, projected onto the British Empire. Popper ingeniously deconstructed nationality, pointing out its complex historical formation and diffuse character, but he never extended this mode of questioning to imperialism. The nation-state was historicized and delegitimized; empires went unexamined and were vindicated. His recollection of historical episodes of imperialism was selective. He recalled Alexander the Great’s cosmopolitanism, the Napoleonic Code, and Habsburg multinationalism, imagined the classical Athenian Empire in an idealized image of the British Empire, and overlooked Spanish colonialism, the Middle Passage, and Nazi Lebensraum. The possibilities for abuse of the imperial ideal—by nationalism, no less—were colossal, but Popper somehow hoped that empire would promote enlightenment rather than racial domination. Imperialism represented cosmopolitanism’s possibility: This was enough. If he presaged Antonio Negri’s and Michael Hardt’s democratic empire, he also bemoaned, at the end of his life, the premature ending of European colonialism. Not permitting a gradual growth of democratic traditions, he said, decolonization left its former subjects, unready for independence, to fend for themselves. Popper presented his views on the Jewish Question as flowing from his cosmopolitanism. Jewish nationality and religion were impediments to cosmopolitanism, he thought; hence, assimilation was a moral imperative. In fact, he got the relationship between cosmopolitanism and assimilation wrong. It was precisely the difficulties of as similation that gave rise to cosmopolitanism. Finding itself excluded from the nation, the Central European Jewish intelligentsia imagined cosmopolitan communities that would accept it. Cosmopolitanism became a precondition to assimilation, not, as Popper surmised, vice versa. An unbridgeable gap separated cosmopolitan dream from Central Europe’s ethnonational realities, and it haunted Popper with a vengeance as he was tackling the Jewish Question.

In stark contrast with his constructionist view of nationalism, Popper held an essentialist racial vision of the Jews and Jewish history. The Hebrew Bible was, he said, the fountainhead of tribal nationalism. Oppressed and persecuted, the Jews in the Babylonian exile created the doctrine of the Chosen People, presaging modern visions of chosen class and race. Both Roman imperialism and early Christian humanitarianism threatened the Jews’ tribal exclusivity. Jewish orthodoxy reacted by reinforcing tribal bonds, shutting Jews off from the world for two millennia. The ghetto was the ultimate closed society, a “petrified form of Jewish tribalism.” Its inhabitants lived in misery, ignorance, and superstition, their separate existence evoking the suspicion and hatred of non-Jews and fueling antisemitism. It was imperative that the ghetto’s gates be opened and that enlightenment would follow. Integration into non-Jewish society was the only solution to the Jewish problem.

For Popper, Zionism reaffirmed tribal and national bonds, and it was thus a colossal mistake. An ethnonational response to antisemitism, it was bound to increase hatred of the Jews and incite a new conflict with the Arabs in Palestine. Until the last decade of his life, Popper rarely expressed himself in public about Zionism or the Jewish Question, but he poured his wrath on Israel in private. Israel was a tragic error. “The status quo is the only possible policy in that maze of nations which peoples Europe and the Near East.” Zionism disrupted the status quo in Palestine. Once Israel was founded, there was no way to undo the mistake, and he “strongly opposed all those who sympathize with the Arab attempts to expel the [Jews].” But he remained highly critical of the Jewish state, insisting that its “racial” character give way to equal citizenship. “I opposed Zionism initially because I was against any form of nationalism,” he said, “but I never expected the Zionists to become racists. It makes me feel ashamed in my origin: I feel responsible for the deeds of the Israeli nationalists.”

A viable Jewish diaspora could have solved Popper’s nationalist quandary, but, in a world threatened by the National Socialists or dominated by their memory, a secure diaspora appeared just as much a dream as cosmopolitanism. A separate Jewish community, however acculturated, thought Popper, endangered the Jews. Antisemitism was to be feared in all places and times, and “living in an overwhelmingly Christian society imposed the obligation to give as little offence as possible— to become assimilated.” The Jews did the opposite. They “insisted that they were proud of their [racial origins]” and triggered a racial war that brought their own destruction. They “invaded politics and journalism,” drawing attention to their wealth and success, and, assuming leadership positions among the socialists, they contributed to the triumph of fascism. Popper descended from cosmopolitanism dangerously close to the antisemitism he feared. The realities of ethnonationalism overwhelmed his cosmopolitan dreams. Jews were not to expect the fulfillment of cosmopolitanism but to accommodate themselves to ethnonationalism. They had to disappear as Jews. They could only become cosmopolitan citizens in a Kantian Kingdom of Ends.

In 1969, an editor inquired if Popper would be willing to be included in the Jewish Chronicle Yearbook. No, answered Popper, “I am of Jewish descent, but . . . I abhor any form of racialism or nationalism; and I never belonged to the Jewish faith. Thus I do not see on what grounds I could possibly consider myself a Jew.” Given his rejection of Jewish identity and his claim to have cut his ties to the Jewish community, his feeling of “shame” in his origin and of “responsibility” for the Zionists seemed odd. At points, he thought of Jewish identity as a historically contingent and subjective commitment; at other times, he treated it as an ethnic destiny. He was ambivalent about his Jewish background, but the problem was not, for the most part, psychological or individual. Subjective identity was his wish, destiny a reality. Antisemitism severely restricted the contingency and subjectivity of Jewish identity. Having first given rise to Jewish cosmopolitanism by denying Jews integration, it then made cosmopolitanism a utopian dream.

The antinomies of cosmopolitanism meant that Popper did not leave much more room for the assimilated Jew than he did for the Zionist. He resolved the tensions between liberalism and nationalism by declaring nationalism a dangerous fiction. Nationality was of secondary importance. Jews were citizens of the “Open Society” but advised to keep a low profile in national politics. A number of Cold War liberals, especially the leadership of the Congress, were sympathetic to the assimilationist imperative, and some were worried about Zionism, but they would not limit their engagement to the cosmopolitan Republic of Scholars. They considered themselves both internationalists and patriots and would not take a back seat in the culture wars.

From: Malachi Haim Hacohen, 2009. “‘The Strange Fact That the State of Israel Exists’: The Cold War Liberals Between Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism”. Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2 Winter, pp. 37-81