Two logics of democracy: Talking it through

I got some good reactions to last week’s newsletter which elaborated the profound differences between the logic of democracy according to representation by election and its logic according to representation by sampling. And lots of questions. Like how would it work. How long would members of a standing citizen assembly sit? What would they decide? So I sat down with Gene Tunny to talk it through. The YouTube video is above, but you can find the audio podcast on my Spotify channel here and immediately below.

The centre that didn’t even try to hold

A few weeks ago I was engaged in a vigorous debate with a good friend who sent me this defence of the media against the depredations of Trump, Musk and the gang. I wasn’t particularly impressed. Yes the traditional media give us a little ‘holding to account’ in all that entertainment they’ve piped into our homes throughout my lifetime. So one can be grateful for small mercies. But the critique was wholly defensive of the media as it is and wholly suspicious of what AI might do.

Well, I’m certainly not here to tell you that profit driven AI will improve our media landscape, but I look on it as simply driving the marginal cost of bullshit to zero. It is thus being used to largely automate the bullshit process of reporting that has become absolutely bog standard.

Brief opening paragraph on the issue

Repeat government media release on it — or run the leak they’ve fitted you up with.

Include some counter-propaganda by someone paid to say the opposite. (Pay no attention whatever to the fact that these words have nothing to do with anyone’s personal convictions. They are all in bad faith.

Call for more research.* (* Oh sorry, I got that last point wrong —that's the AI routine in academia, not news. Anyway, and apropos of nothing much, AI is already improving abstracts.)

Anyway, I sent him Bill Clinton above. Yes, Bill’s being self-serving. He did rather a lot of that. Still does. But what he says is also devastatingly right. The media sits at the centre of discussion — between protagonists of different positions.

I wrote a whole article on this and how fundamental it is for those institutions that convene spaces for discussion not to fall for what I called ‘the competition delusion’. That is the idea that the truth somehow emerges from the vigorous competition in a ‘free market for ideas’. As we’ve had dramatically illustrated since the advent of social media, chaos, not insight, is the more likely outcome. But it was always evident in mass media, and no-one put the issue better than Bill Clinton.

In a game of tennis the players compete, but the umpire occupies the shared centre. Their job is not to entertain. Nor is it to compete. Their job is unitary. It is the often mundane, essential ingredient to ensure that what gets produced has some value.

Now journalism needs to turn a quid which, in the current landscape means it needs to attract eyeballs. And the sad fact is that the lowest cost way to do that is either to simply go partisan — like Fox News or its pale mirror image MSNBC — or to perform the vacant balance set out in the dot points above. There is journalism that tries to defy these two formulae, and for all I know the author of the piece defending the media is one of them, but if, in their advocacy for their position, there are no intimations of the bankruptcy of where we’ve got to now, I’m not going to pay much attention.

I’m going to be wondering what kinds of institutions might do better than that. And this week I was reminded of Bill’s words all over again — as I expect I will be every week for some years now, and perhaps for the rest of my life. This week there was a plane crash and Donald Trump had an instant opinion on it. Good for him. My next-door neighbour might have an opinion about it too. But Trump didn’t know anything about the crash. He was just making stuff up. My next door neighbour can do that too.

Anyway, like the best politicians Bill can be compelling when he wants to be.

The centre and the truth

The locust plague comes for Paul Krugman

The NYT have the best economic journalist of his generation, a Nobel laureate no less. (Which is not to say I haven’t had my differences with him.) But they still sent the middle managers in to do their magic. So Paul has set himself up at Substack and hasn’t had as much fun in years. He can write faster, write more. There are just no downsides.

Except for the Times of course and they’re licking their wounds. After all, intuitively it doesn’t seem a good idea to get people who don’t know much to tell brilliant people what they can and can’t do. And how they should be incentivised. But that’s the norm. So much so that there are only a few famous counter examples. DARPA, The Manhattan Project.

Anyway, here’s Paul explaining his departure.

Noah feels his pain: based on his own pain at Bloomberg

And Paul has been pumping out the posts.

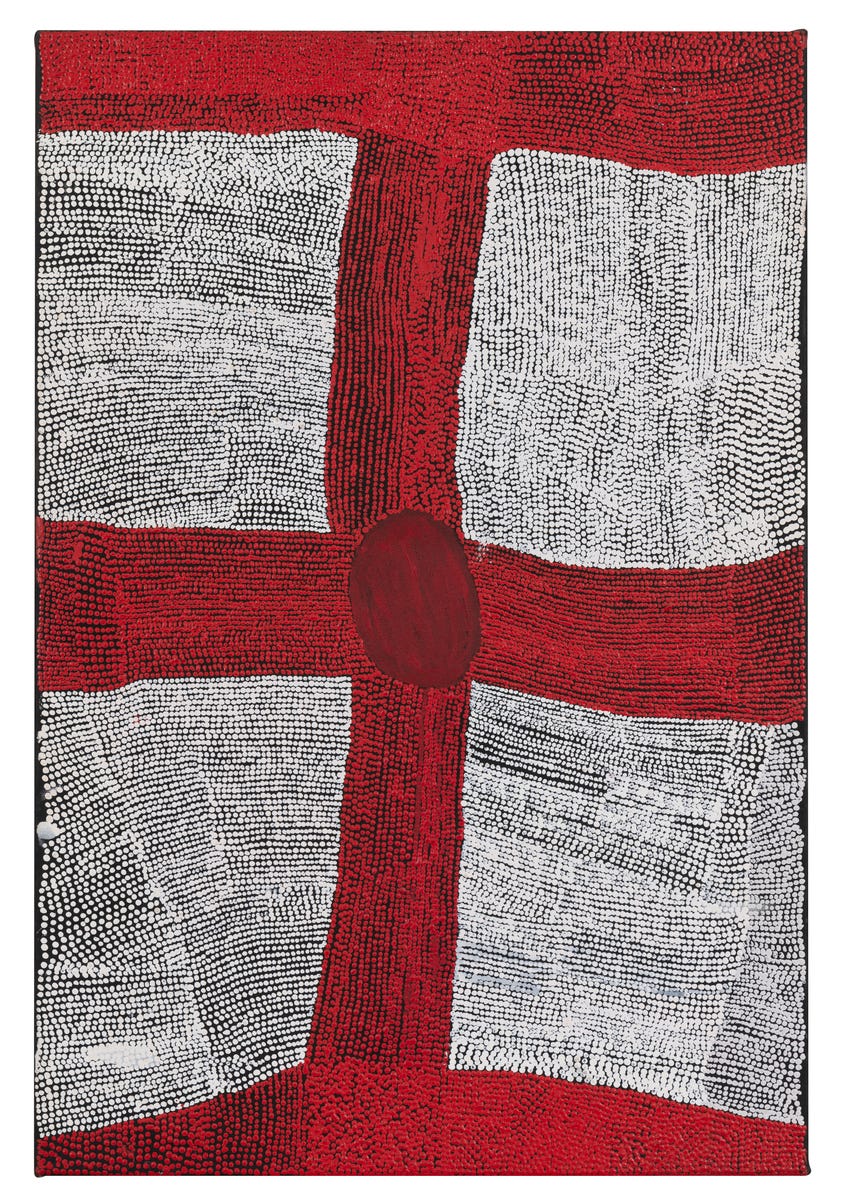

I love pictures like this: I wonder why?

Maybe it has something to do with colour?

Then there’s this

Does Israel have a right to exist?

A subscriber drew my attention to this piece. He is a public servant (i.e. a deep state operative) and so probably doesn’t want to be named. (After all, Hannah Arendt described bureaucracy as ‘government by noone’ and she had a point.)

A couple of years back there was lots of excitement about a slogan. “Trans women are women”. That’s fine, except that in certain very specific circumstances maybe they’re not. Likewise “Israel has a right to exist”. And for that matter, the idea that ‘From the river to the sea” is genocidal. It is for some. And some of those folks are Israeli, and some of them are the Prime Minister.

Anyway, whether it’s trans activists or Israelis engaging in long-term self-harm, people using slogans to answer difficult questions are not doing themselves or anyone else any favours.

In today’s Washington, which seethes with partisan acrimony, Democrats and Republicans at least agree on this: Israel has a right to exist. … This is not the way Washington politicians generally talk about other countries. They usually start with the rights of individuals, and then ask how well a given state represents the people under its control. …

In 2020, Secretary Pompeo declared in a speech that America’s founders believed that “government exists not to diminish or cancel the individual’s rights at the whims of those in power, but to secure them.” Do states that deny individual rights have a “right to exist” in their current form? The implication of Mr. Pompeo’s words is that they do not.

What if we talked about Israel that way? Roughly half the people under Israeli control are Palestinian. Most of those — the residents of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip — cannot become citizens of the state that wields life-or-death power over them. Israel wielded this power in Gaza even before Hamas invaded on Oct. 7, 2023, since it controlled the Strip’s airspace, coastline, population registry and most of its land crossings, thus turning Gaza into what Human Rights Watch called “an open-air prison.” …

Last month, Mr. Blinken promised that the United States would help Syrians build an “inclusive, nonsectarian” state. The Israel that exists today manifestly fails that test. …

Some of the Bible’s greatest heroes — Moses and Mordechai among others — risk their lives by refusing to treat despotic rulers as divine. In refusing to worship state power, they reject idolatry, a prohibition so central to Judaism that, in the Talmud, Rabbi Yochanan called it the very definition of being a Jew.

Today, however, this form of idolatry — worship of the state — seems to suffuse mainstream American Jewish life. It is dangerous to venerate any political entity. But it’s especially dangerous to venerate one that classifies people as legal superiors or inferiors based on their tribe. When America’s most influential Jewish groups, like American leaders, insist again and again that Israel has a right to exist, they are effectively saying there is nothing Israel can do — no amount of harm it can inflict upon the people within its domain — that would require rethinking the character of the state.

They have done so even as Israel’s human-rights abuses have grown ever more blatant. For almost 16 years, since Benjamin Netanyahu returned to power in 2009, Israel has been ruled by leaders who boast about preventing Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip from establishing their own country, thus consigning them to live as permanent noncitizens, without basic rights, under Israeli rule. …

American Jewish leaders often say a Jewish state is essential to protecting Jewish lives. Jews cannot be safe unless Jews rule. I understand why many American Jews, who as a general rule believe that states should not discriminate based on religion, ethnicity or race, make an exception for Israel. It’s a response to our traumatic history as a people. But global antisemitism notwithstanding, diaspora Jews — who stake our safety on the principle of legal equality — are far safer than Jews in Israel.

This is not a coincidence. Countries in which everyone has a voice in government tend to be safer for everyone. A 2010 study of 146 instances of ethnic conflict around the world since World War II found that ethnic groups that were excluded from state power were three times more likely to take up arms as those that enjoyed representation in government. …

Why do Israeli Jews find Palestinian citizens so much less threatening than Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza? In large measure, because Palestinian citizens can vote in Israeli elections. So, although they face severe discrimination, they at least have some peaceful and lawful methods for making their voices heard. Compare that with Palestinians in Gaza, or the West Bank, who have no legal way to influence the state that bombs and imprisons them.

When you deny people basic rights, you subject them to tremendous violence. And, sooner or later, that violence endangers everyone. In 1956, a 3-year-old named Ziyad al-Nakhalah saw Israeli soldiers murder his father in the Gazan city of Khan Younis. Almost 70 years later, he heads Hamas’s smaller but equally militant rival, Islamic Jihad.

On Oct. 7, Hamas and Islamic Jihad fighters killed about 1,200 people in Israel and abducted about 240 others. Israel has responded to that massacre with an assault on Gaza that the British medical journal The Lancet estimates has killed more than 60,000 people, and destroyed most of the Strip’s hospitals, schools and agriculture. Gaza’s destruction serves as a horrifying illustration of Israel’s failure to protect the lives and dignity of all the people who fall under its authority.

The failure to protect the lives of Palestinians in Gaza ultimately endangers Jews. In this war, Israel has already killed more than one hundred times as many Palestinians in Gaza as it did in the massacre that took the life of Mr. al-Nakhalah’s father. How many 3-year-olds will still be seeking revenge seven decades from now? …

Yet in the name of Jewish safety, American Jewish organizations appear to countenance virtually anything Israel does to Palestinians, even a war that both Amnesty International and the eminent Israeli-born Holocaust scholar Omer Bartov now consider genocide. What Jewish leaders and American politicians can’t countenance is equality between Palestinians and Jews — because that would violate Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state.

Karl Polanyi: if he’s right is he useful?

WWII wasn’t much good for a lot of people. But it’s remarkable how much it concentrated people’s minds. Five books of great insight were published in early 1940s.

Hayek’s Road to Serfdom (even if I always thought the name Tim Dunlop gave his blog was better — The Road to Surfdom.)

Schumpeter’s, Capitalism, Socialism, Democracy.

James Burnham’s The Managerial Revolution and The Machiavellians; and

Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation.

Subscriber Robert Banks sent me Stefan Collini’s review of the latter book. (This link via Pocket might work better if you encounter the LRB’s paywall. Collini is 80 years late, but we’ll let that go through to the keeper. I’ve always liked the cut of Polanyi’s jib. He was pushing back against the re-intellectualisation of laissez-faire by the Austrian Ludwig von Mises and the early stirrings of neoliberalism from Mises’ pupil Friedrich Hayek.

Polanyi’s argument was that the disembodied idea of the market that the 19th century political economists spoke of was an abstraction, not the reality. He argued that the ‘markets’ that developed in the 19th century, were historical and political constructs. They were shaped by power — and particularly the power of the wealthy over the poor and the working classes. Unlike Marxists at the time, Polanyi conceded an important role for markets, but insisted on the importance of their being embodied within society and within wider economic and political structures.

But as right as he might have been, if you agree with his general argument, I don’t think he was particularly useful in helping you act on that sentiment. Here are some passages from the review.

A common thread in the variously inflected accounts of this transformation was the claim that, alongside the new economic practices and social arrangements, there also emerged a new way to conceptualise patterns of interaction, perhaps even a new way to understand human motivation. Political economy was a study (a ‘science’ in the eyes of its most enthusiastic votaries) that purported to proceed deductively from a few simple, incontestable axioms about human behaviour to arrive at universally valid ‘laws’ describing the relations of supply and demand and similar matters. This intellectual enterprise, according to its numerous critics, not only had damaging political consequences in seeming to validate policies of laissez-faire: it also encouraged a wider disregard for the complexities of human behaviour and the variability of historical and cultural circumstances. For those intent on imagining a future form of society that would not be disfigured by the perceived exploitation and injustice (and, no less important for some critics, ugliness) of the encroaching industrial system, it became imperative to try to dethrone the abstractions of political economy. …

Although idiosyncratic in its concentration on the principles underlying the old and new Poor Laws, Polanyi’s account of the industrial revolution, and especially his understanding of it as creating a ‘new civilisation’, was not unusual in British social thought in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. What was distinctive was the way he tied that historical story to an analysis of what had happened in the interwar years – cataclysmically in Continental Europe; less dramatically, but still unmistakably, in Britain and the US. The motor force of The Great Transformation was Polanyi’s contention that a thoroughgoing unregulated market society was an impossible dream: he repeatedly referred to the idea of such a society as ‘utopian’ (hence one of the rejected titles). The so-called ‘double movement’, in which the excesses of the free market were compensated for, or patched up, was one expression of this truth. More ambitiously, he tried to represent the economic and political crises of the decades after 1914 as the inevitable outcome of the same self-defeating logic. The exact mechanism in this case was less clear: the attempt to maintain free trade based on the gold standard in a world of competing national autarkies signalled, he argued, the death throes of a doomed project, though there seems more than a hint of circular reasoning in this interpretation. In any event, Polanyi’s book was an exceptionally bold effort to make sense of contemporary developments on an international scale by telling a quasi-historical story that linked the spinning jenny, Malthus and the Poor Law to the Wall Street Crash, the rise of fascism and the vogue for planning. The thesis that held the story together could be stated with brutal clarity: ‘The origins of the cataclysm lay in the utopian endeavour … to set up a self-regulating market system.’ Or as he put it in one of his pithiest apothegms: ‘In order to comprehend German fascism, we must revert to Ricardian England.’ …

If the cataclysm marked the end of 19th-century civilisation, it also signalled the arrival of a new form of social organisation. Polanyi claimed that he had seen the future and the future was social. That is to say, the emphasis on unregulated competition was now yielding to a recognition of what he called ‘the reality of society’ and the need for correspondingly collective forms of social responsibility. He was not alone in detecting moves in this direction in Roosevelt’s New Deal and subsequently in Attlee’s welfare state, though, like so many, he came to be disappointed in the achievements of the 1945-51 Labour government. And he argued that this reorientation towards the social was now an unstoppable tendency more widely: ‘Within the nations we are witnessing a development under which the economic system ceases to lay down the law to society and the primacy of society over that system is secured.’ The final chapter of The Great Transformation makes the case that freedom, far from being incompatible with a planned society and a regulated market, is in fact meaningful only under such conditions. Enthusing about this development, Polanyi in his peroration hit a utopian note of his own: ‘The passing of the market economy can become the beginning of an era of unprecedented freedom.’ This was a hot topic in 1940s Britain – both Mannheim and Eliot, for example, made it salient in their contrasting social diagnoses – but in this form it now has a dated feel, and of course the larger prediction about the passing of market society has, to put it mildly, not worn well.

The tendencies referred to in these paragraphs smack of intellectual hubris and confusion. Many things are rolled together as if by saying things one could sympathise with, one had solved the problems of just how one might ‘re-embed’ the market in life in some healthy way. It’s also remarkable that Polanyi shares with all the others in the list above the idea that society was headed towards some corporate form — of the sort that is foreshadowed in Art Deco murals in which the working man and the professional together reshaping the social, political and physical world. Schumpeterian John Kenneth Galbraith later christened this the ‘technostructure’. All the others except Hayek that is, whose soft fanaticism kept him focused on his own goal of the market as the paradigm social institution. (And if things didn’t go that way, any fear Hayek might have had of corporatism was only as a waystation to totalitarianism.)

Today Karl is more famous than his younger brother Michael, precisely because his writing addressed the ideological chasm between left and right so directly — always a better way to go viral. Michael was no slouch in that department, entering it from the opposite side to his brother. He was a founding member of Hayek’s Mont Pèlerin Society, but drifted away as its internal logic asserted itself.

Michael also came up with apocalyptic connections between European modernity and mid-20th century totalitarianism. But I think Michael achieved far more, in terms of forging new and compelling intellectual ground. And, against the difficulties of doing so with Karl’s thought, Michael’s thought can be used to pinpoint what’s gone wrong. And though Michael Polanyi did little to address the next step, I don’t think it’s so hard to do.

To be continued …

Some stunners from D’Lan Contemporary

Resistentialism: Who knew?

I’ve been reading At the Existentialist Café which I’ve been really enjoying. It was where I learned of this.

From The New York Times, June 13, 1948

Thingness of Things Resistentialism, it says here, is the very latest, By PAUL F. JENNINGS:

PARIS: HATRED of one’s father at Victoria. Clapham, a nightmare of cream-painted plumbing and baths in the sky. Sorrow and Angst over the fish in the dining car. Then Dover, looking guiltily northward at the death of the spirit. After the suicidal milk-bars, the red-haired men on the trams, what heart’s-ease to be in Paris once more—to see the familistéres, the cyclisme, the Métro, to hear the grand cri sangloté du monde; the insouciant talk of the pédisseries, the badinage of the épiceries, and above all the bubbling creative activity of the little residentialist cafes where the disciples of Pierre-Marie Ventre meet to discuss this fascinating new philosophy.

Listening to Ventre for several evenings, I perceived that Paris still brandishes the sword of European thought, flashing brightly against the dull philistine sky.

Resistentialism is a philosophy of tragic grandeur. It is difficult to give an account of it in textbook English after hearing Ventre’s witty aphorisms, but I will try.

Resistentialism derives its name from its central thesis that Things (res) resist (résister) men. Philosophers have become excited at various times, says Ventre, about Psycho - Physical Parallelism, about Idealism, about the I-Thou relation, about Pragmatism. All these were, so to speak, pre-atomic philosophies. They were concerned merely with what men think about Things. Now resistentialism is the philosophy of what Things think about us.

The tragic, cosmic answer, after centuries of man’s attempts to dominate Things, is our progressive losing of the battle. “Things are against us” is the nearest I can get to the untranslatable lucidity of Ventre’s profound aphorism, “Les choses sont contre nous.”

Of course, resistentialism represents to some extent a synthesis of previous European thought. The hostility of Things has been dimly perceived by other philosophers. (Continued on Page 20)

Goethe, for instance, said that “three times has an apple proved fatal. First to the human race, in the fall of Adam, secondly to Troy, through the gift of Paris; and, last of all, to science through the fall of Newton’s apple” (Werke, XVI, 17). This line was, of course, pursued by Martin Freidegg in his monumental Werke (Leipzig: 1887), and, of course, Martin Heidansieck (Werke, Leipzig: 1888). The latter reached the position that man could not control Things, but although there are flashes of perception of the actual hostility of Things in his later work, it was left to Ventre to make the brilliant jump to the resistentialist conception of the planned, numbuous, quasi-intellectual opposition of Things as a single force against us.

ONS reason for the appeal of resistentialism to the modern mind is its bridging of the gift between philosophy and science. Indeed, some of Ventre’s followers go so far as to claim that resistentialism is just a transcendental version of modern physics. There have been experiments in which pieces of toast and marmalade were dropped on various samples of carpet arranged in order of quality from our matting to the finest Kirman rugs; the marmalade downward incidence was found to vary directly as the quality of carpet.

More recently researches in the American field by Noya and Crangenbacker, two Americans, have involved literally thousands of experiments in which subjects of all ages and sexes, sitting in chairs of every conceivable kind, dropped various kinds of pencil. In only three cases did the pencil come to rest within easy reach.

Gonk’s Hypothesis, formulated by Professor Gonk of the Cambridge Trichological Institute, states that a subject who has rubbed a wet shaving brush over his face before applying the cream cannot, however long and furiously he shakes the brush, prevent water from dribbling down his forearm and wetting his sleeve once he starts shaving.

Ventre, however, scorns the false positivism of the scientists with their fussy desire to dominate. Things cannot be dominated. Residentialism is a tragic philosophy. It sees that man is doomed by Things the moment he attempts to achieve anything outside his own “mind,” which, like Disney’s flying mouse, is Not A Thing At All. To the resistentialist man is no-Thing, or rather a pseudo-Thing (the nearest I can get to Venice’s subtle expression pseudo-chose). Things are the only reality possessing a power of action to which we can never aspire.” The resistentialist ideal is to free man from his tragic destiny of Thing-hauntedness by refusing to enter into relation with Things. Things always win, and man can only be free from them by not doing anything at all.

This brings me to the activities of resistentialism. Readers are already aware of the profound effects of the new philosophy on Art and Literature. We have already seen Ventre’s play “Puits Clos,” which expresses resistentialism in a dramatic parable in which three old men walk around ceaselessly at the bottom of a well. There are also some bricks in the well. These symbolize Things, and all the old men hate the bricks as much as they do each other. The play is full of their pitfall attempts to throw the bricks out of the top of the well, but they can, of course, never throw high enough, and the bricks always fail back on them.

In the musical field there is already a school of resistentialist composers among the younger men, notably Dufay and Kódak. Recognition of the thing-ness of musical instruments—the tendency of the French horn to make horrible glubbing noises, the tragic mathematical fact that if music goes at more than a certain critical speed the friction of the violinist’s bow will set fire to the strings—is behind Kódak’s interesting sinfonette for horns, trumpets, strings, sousphones and cymbals without any players.

At one of the resistentialist cafés Agfa, one of the painters in Ventre’s entourage, told me that he is contemplating an exhibition of his work in London. If this bold venture succeeds it will be a great day for the people of London. But of course it won’t be the same thing as here, in Paris, among the insouciant talk of the pâtisseries, the badinage of the épiceries.

Diane Coyle on the Metaphysical Club

Diane Coyle publishes a steady stream of reviews on her site and, as I had also read this book when it came out, and (though I’ve not re-read it) I agreed with everything she wrote here, I thought I’d reproduce it for you here.

I re-read a book I first read in 2002 when the first UK paperback was published, Louis Menand’s magnificent The Metaphysical Club: A story of ideas in America. It takes a sweeping view of the reshaping of the climate of ideas in the US after the Civil War, when pre-war traditions were replaced thanks to a combination of influences: the professionalisation of intellectual life in universities, the impact of scientific discovery particularly Darwin, and indeed the consequences of the Union victory. By the late 19th century the broadly defined pragmatist perspective that lasted until the 1960s – including an accommodation among White Americans over the status of African-Americans – was in place. The story is told though the intertwined histories of William James, Charles Peirce, Oliver Wendell Holmes and John Dewey.

The book lived up to my memory of its excellence, although newly poignant as the idea of an intellectual life among the new US ruling class seems increasingly like a contradiction in terms. I picked out moments that speak to my current preoccupations. For example, on the impact of The Origin of Species, that it emphasized difference or variation as an organising principle, not common characteristics. Some quotes that seem particularly relevant now: Everything human beings do by choice rather than by instinct, and course of conduct they choose when they might have chosen differently, is a moral action.”

William James arguing that society is the fact of life, and the idea of a non-social individual is pure abstraction, while Dewey agreed that there are no individuals without society: “Dewey taught that doing is why there is knowing.” Holmes meanwhile argued that experience – which defines the practice of justice – “is social, not psychological”, his construct of how the ‘reasonable man’ would judge being defined with respect to society.

Menand concludes: “Everything James and Dewey wrote as pragmatists boils down to a single claim: people are the agents of their own destinies. They dispel the fatalism that haunts almost every 19th century system of thought. … What Holmes did not share with those thinkers was their optimism. He did not believe that the experimental spirit will necessarily lead us, ultimately, down the right path. Democracy is an experiment, and it is in the nature of experiments sometimes to fail.” As he had seen it fail as a combatant in the Civil War.

“It’s about community more than winning”: Cathy McGowan

Intersectionality takes a hit

Is There Intersectional Labor Market Discrimination?

We present new and rich evidence on intersectional discrimination in labor markets, focusing on wages in the traditional residual wage differential approach to discrimination. We interpret “intersectional discrimination” in the framework of interactions, in which discrimination along two intersecting dimensions leads to discrimination that exceeds the sum of its parts. We make three contributions. First, we resolve puzzling contradictory findings on intersectional discrimination in existing research – with studies using similar data and methods reaching diametrically opposite conclusions. Second, we extend the analysis of potential intersectional discrimination to more dimensions than have typically been considered in past research. Third, we explore issues of bias in the wage equations we estimate from selection on employment. Our overall conclusion from these different types of evidence is that there is little or no evidence consistent with intersectional discriminat! ion in wage differentials among the large set of groups (and combinations of groups) we study, and indeed most evidence points in the opposite direction.

Pretty interesting anti Trump post given the author

Noah thinks the US might be able to re-shore manufacturing

(I wouldn’t try this at home — i.e. in Australia — which is much smaller and has higher minimum wages.)

Heaviosity half hour

The parable of the missed Supreme Court clerkship

An excerpt from Peter Thiel’s From Zero to One

Peter Thiel is a smart guy. He’s right too that, as Schumpeter pointed out in the 1930s, monopoly and the striving for it, drives innovation. That, at least according to the abstractions of economics, a perfectly competitive business can’t innovate, because it’s making precisely the same product as its competitors and it can't invest in doing things differently without becoming uncompetitive against other businesses that are not doing that.

But it’s not true that such a world is ‘death’ to business, nor that a perfectly competitive business makes no profits. It makes ‘normal profits’. Because it needs capital it obtains that capital in a perfectly competitive capital market at a price — which is the rate of return required to be entrusted with the money given the risk.

Anyway, I was going to make this a more substantial post but have no longer got the time to do so. But it was interesting reading this book and thinking just how vividly he sees the prospects for monopoly. He associates capitalism with monopoly. Yes, capitalism is full of pockets of monopoly, but capitalism has never been much chop without the dialectic between competition and monopoly. I expect Thiel would agree with that, but you could miss it reading his book.

Anyway, now we get to see Thiel’s thinking in action. The world has been hogtied by bureaucrats. I kind of agree. But the recipe he has for solving the problem is a tad on the simplistic side — focusing on the dysfunctionality of modern governance but with the typical business person’s impatience, imagining that sweeping inefficient stuff away is a good idea. Sounds good I know. Quite a bit of it will be. But what if, however inefficiently they’re being performed, some of those tasks are indispensable. (Ask the good folk of Flint, Michigan.) Then you’d need to try to fix the problem. Sweeping it away will make things worse.

I don’t predict it will end well. But what would I know?

Anyway, there are plenty of other, interesting speculations in the passage below — which I found stimulating, and occasionally a little on the unhinged side.

The airlines compete with each other, but Google stands alone. Economists use two simplified models to explain the difference: perfect competition and monopoly.

“Perfect competition” is considered both the ideal and the default state in Economics 101. So-called perfectly competitive markets achieve equilibrium when producer supply meets consumer demand. Every firm in a competitive market is undifferentiated and sells the same homogeneous products. Since no firm has any market power, they must all sell at whatever price the market determines. If there is money to be made, new firms will enter the market, increase supply, drive prices down, and thereby eliminate the profits that attracted them in the first place. If too many firms enter the market, they’ll suffer losses, some will fold, and prices will rise back to sustainable levels. Under perfect competition, in the long run no company makes an economic profit.

The opposite of perfect competition is monopoly. Whereas a competitive firm must sell at the market price, a monopoly owns its market, so it can set its own prices. Since it has no competition, it produces at the quantity and price combination that maximizes its profits.

To an economist, every monopoly looks the same, whether it deviously eliminates rivals, secures a license from the state, or innovates its way to the top. In this book, we’re not interested in illegal bullies or government favorites: by “monopoly,” we mean the kind of company that’s so good at what it does that no other firm can offer a close substitute. Google is a good example of a company that went from 0 to 1: it hasn’t competed in search since the early 2000s, when it definitively distanced itself from Microsoft and Yahoo!

Americans mythologize competition and credit it with saving us from socialist bread lines. Actually, capitalism and competition are opposites. Capitalism is premised on the accumulation of capital, but under perfect competition all profits get competed away. The lesson for entrepreneurs is clear: if you want to create and capture lasting value, don’t build an undifferentiated commodity business. …

The problem with a competitive business goes beyond lack of profits. Imagine you’re running one of those restaurants in Mountain View. You’re not that different from dozens of your competitors, so you’ve got to fight hard to survive. If you offer affordable food with low margins, you can probably pay employees only minimum wage. And you’ll need to squeeze out every efficiency: that’s why small restaurants put Grandma to work at the register and make the kids wash dishes in the back. Restaurants aren’t much better even at the very highest rungs, where reviews and ratings like Michelin’s star system enforce a culture of intense competition that can drive chefs crazy. (French chef and winner of three Michelin stars Bernard Loiseau was quoted as saying, “If I lose a star, I will commit suicide.” Michelin maintained his rating, but Loiseau killed himself anyway in 2003 when a competing French dining guide downgraded his restaurant.) The competitive ecosystem pushes people toward ruthlessness or death.

A monopoly like Google is different. Since it doesn’t have to worry about competing with anyone, it has wider latitude to care about its workers, its products, and its impact on the wider world. Google’s motto—“Don’t be evil”—is in part a branding ploy, but it’s also characteristic of a kind of business that’s successful enough to take ethics seriously without jeopardizing its own existence. In business, money is either an important thing or it is everything. Monopolists can afford to think about things other than making money; non-monopolists can’t. In perfect competition, a business is so focused on today’s margins that it can’t possibly plan for a long-term future. Only one thing can allow a business to transcend the daily brute struggle for survival: monopoly profits. …

CREATIVE MONOPOLY means new products that benefit everybody and sustainable profits for the creator. Competition means no profits for anybody, no meaningful differentiation, and a struggle for survival. So why do people believe that competition is healthy? The answer is that competition is not just an economic concept or a simple inconvenience that individuals and companies must deal with in the marketplace. More than anything else, competition is an ideology—the ideology—that pervades our society and distorts our thinking. We preach competition, internalize its necessity, and enact its commandments; and as a result, we trap ourselves within it—even though the more we compete, the less we gain.

This is a simple truth, but we’ve all been trained to ignore it. Our educational system both drives and reflects our obsession with competition. Grades themselves allow precise measurement of each student’s competitiveness; pupils with the highest marks receive status and credentials. We teach every young person the same subjects in mostly the same ways, irrespective of individual talents and preferences. Students who don’t learn best by sitting still at a desk are made to feel somehow inferior, while children who excel on conventional measures like tests and assignments end up defining their identities in terms of this weirdly contrived academic parallel reality.

And it gets worse as students ascend to higher levels of the tournament. Elite students climb confidently until they reach a level of competition sufficiently intense to beat their dreams out of them. Higher education is the place where people who had big plans in high school get stuck in fierce rivalries with equally smart peers over conventional careers like management consulting and investment banking. For the privilege of being turned into conformists, students (or their families) pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in skyrocketing tuition that continues to outpace inflation. Why are we doing this to ourselves?

I wish I had asked myself when I was younger. My path was so tracked that in my 8th-grade yearbook, one of my friends predicted—accurately—that four years later I would enter Stanford as a sophomore. And after a conventionally successful undergraduate career, I enrolled at Stanford Law School, where I competed even harder for the standard badges of success.

The highest prize in a law student’s world is unambiguous: out of tens of thousands of graduates each year, only a few dozen get a Supreme Court clerkship. After clerking on a federal appeals court for a year, I was invited to interview for clerkships with Justices Kennedy and Scalia. My meetings with the Justices went well. I was so close to winning this last competition. If only I got the clerkship, I thought, I would be set for life. But I didn’t. At the time, I was devastated.

In 2004, after I had built and sold PayPal, I ran into an old friend from law school who had helped me prepare my failed clerkship applications. We hadn’t spoken in nearly a decade. His first question wasn’t “How are you doing?” or “Can you believe it’s been so long?” Instead, he grinned and asked: “So, Peter, aren’t you glad you didn’t get that clerkship?” With the benefit of hindsight, we both knew that winning that ultimate competition would have changed my life for the worse. Had I actually clerked on the Supreme Court, I probably would have spent my entire career taking depositions or drafting other people’s business deals instead of creating anything new. It’s hard to say how much would be different, but the opportunity costs were enormous. All Rhodes Scholars had a great future in their past.

Peter Thiel’s division of the world into four states from the above two qualities.

1. Definite Optimist

Believes the future will be better and actively plans to create it through deliberate actions (e.g., entrepreneurs, builders).

2. Indefinite Optimist

Expects the future to improve but relies on broader forces like markets or technological progress rather than specific plans (e.g., passive investors).

3. Definite Pessimist

Foresees a worsening future and prepares by making concrete plans to mitigate expected decline (e.g., survivalists).

4. Indefinite Pessimist

Anticipates decline but lacks a clear plan or ability to act, resulting in resignation or inaction (e.g., stagnation-minded individuals).

OUR INDEFINITELY OPTIMISTIC WORLD

Indefinite Finance

While a definitely optimistic future would need engineers to design underwater cities and settlements in space, an indefinitely optimistic future calls for more bankers and lawyers. Finance epitomizes indefinite thinking because it’s the only way to make money when you have no idea how to create wealth. If they don’t go to law school, bright college graduates head to Wall Street precisely because they have no real plan for their careers. And once they arrive at Goldman, they find that even inside finance, everything is indefinite. It’s still optimistic—you wouldn’t play in the markets if you expected to lose—but the fundamental tenet is that the market is random; you can’t know anything specific or substantive; diversification becomes supremely important.

The indefiniteness of finance can be bizarre. Think about what happens when successful entrepreneurs sell their company. What do they do with the money? In a financialized world, it unfolds like this:

• The founders don’t know what to do with it, so they give it to a large bank.

• The bankers don’t know what to do with it, so they diversify by spreading it across a portfolio of institutional investors.

• Institutional investors don’t know what to do with their managed capital, so they diversify by amassing a portfolio of stocks.

• Companies try to increase their share price by generating free cash flows. If they do, they issue dividends or buy back shares and the cycle repeats.

At no point does anyone in the chain know what to do with money in the real economy. But in an indefinite world, people actually prefer unlimited optionality; money is more valuable than anything you could possibly do with it. Only in a definite future is money a means to an end, not the end itself.

Indefinite Politics

Politicians have always been officially accountable to the public at election time, but today they are attuned to what the public thinks at every moment. Modern polling enables politicians to tailor their image to match preexisting public opinion exactly, so for the most part, they do. Nate Silver’s election predictions are remarkably accurate, but even more remarkable is how big a story they become every four years. We are more fascinated today by statistical predictions of what the country will be thinking in a few weeks’ time than by visionary predictions of what the country will look like 10 or 20 years from now.

And it’s not just the electoral process—the very character of government has become indefinite, too. The government used to be able to coordinate complex solutions to problems like atomic weaponry and lunar exploration. But today, after 40 years of indefinite creep, the government mainly just provides insurance; our solutions to big problems are Medicare, Social Security, and a dizzying array of other transfer payment programs. It’s no surprise that entitlement spending has eclipsed discretionary spending every year since 1975. To increase discretionary spending we’d need definite plans to solve specific problems. But according to the indefinite logic of entitlement spending, we can make things better just by sending out more checks.

Indefinite Philosophy

You can see the shift to an indefinite attitude not just in politics but in the political philosophers whose ideas underpin both left and right.

The philosophy of the ancient world was pessimistic: Plato, Aristotle, Epicurus, and Lucretius all accepted strict limits on human potential. The only question was how best to cope with our tragic fate. Modern philosophers have been mostly optimistic. From Herbert Spencer on the right and Hegel in the center to Marx on the left, the 19th century shared a belief in progress. (Remember Marx and Engels’s encomium to the technological triumphs of capitalism from this page.) These thinkers expected material advances to fundamentally change human life for the better: they were definite optimists.

In the late 20th century, indefinite philosophies came to the fore. The two dominant political thinkers, John Rawls and Robert Nozick, are usually seen as stark opposites: on the egalitarian left, Rawls was concerned with questions of fairness and distribution; on the libertarian right, Nozick focused on maximizing individual freedom. They both believed that people could get along with each other peacefully, so unlike the ancients, they were optimistic. But unlike Spencer or Marx, Rawls and Nozick were indefinite optimists: they didn’t have any specific vision of the future.

Their indefiniteness took different forms. Rawls begins A Theory of Justice with the famous “veil of ignorance”: fair political reasoning is supposed to be impossible for anyone with knowledge of the world as it concretely exists. Instead of trying to change our actual world of unique people and real technologies, Rawls fantasized about an “inherently stable” society with lots of fairness but little dynamism. Nozick opposed Rawls’s “patterned” concept of justice. To Nozick, any voluntary exchange must be allowed, and no social pattern could be noble enough to justify maintenance by coercion. He didn’t have any more concrete ideas about the good society than Rawls: both of them focused on process. Today, we exaggerate the differences between left-liberal egalitarianism and libertarian individualism because almost everyone shares their common indefinite attitude. In philosophy, politics, and business, too, arguing over process has become a way to endlessly defer making concrete plans for a better future.

Indefinite Life

Our ancestors sought to understand and extend the human lifespan. In the 16th century, conquistadors searched the jungles of Florida for a Fountain of Youth. Francis Bacon wrote that “the prolongation of life” should be considered its own branch of medicine—and the noblest. In the 1660s, Robert Boyle placed life extension (along with “the Recovery of Youth”) atop his famous wish list for the future of science. Whether through geographic exploration or laboratory research, the best minds of the Renaissance thought of death as something to defeat. (Some resisters were killed in action: Bacon caught pneumonia and died in 1626 while experimenting to see if he could extend a chicken’s life by freezing it in the snow.)

We haven’t yet uncovered the secrets of life, but insurers and statisticians in the 19th century successfully revealed a secret about death that still governs our thinking today: they discovered how to reduce it to a mathematical probability. “Life tables” tell us our chances of dying in any given year, something previous generations didn’t know. However, in exchange for better insurance contracts, we seem to have given up the search for secrets about longevity. Systematic knowledge of the current range of human lifespans has made that range seem natural. Today our society is permeated by the twin ideas that death is both inevitable and random.

Meanwhile, probabilistic attitudes have come to shape the agenda of biology itself. In 1928, Scottish scientist Alexander Fleming found that a mysterious antibacterial fungus had grown on a petri dish he’d forgotten to cover in his laboratory: he discovered penicillin by accident. Scientists have sought to harness the power of chance ever since. Modern drug discovery aims to amplify Fleming’s serendipitous circumstances a millionfold: pharmaceutical companies search through combinations of molecular compounds at random, hoping to find a hit.

But it’s not working as well as it used to. Despite dramatic advances over the past two centuries, in recent decades biotechnology hasn’t met the expectations of investors—or patients. Eroom’s law—that’s Moore’s law backward—observes that the number of new drugs approved per billion dollars spent on R&D has halved every nine years since 1950. Since information technology accelerated faster than ever during those same years, the big question for biotech today is whether it will ever see similar progress. Compare biotech startups to their counterparts in computer software:

Biotech startups are an extreme example of indefinite thinking. Researchers experiment with things that just might work instead of refining definite theories about how the body’s systems operate. Biologists say they need to work this way because the underlying biology is hard. According to them, IT startups work because we created computers ourselves and designed them to reliably obey our commands. Biotech is difficult because we didn’t design our bodies, and the more we learn about them, the more complex they turn out to be.

But today it’s possible to wonder whether the genuine difficulty of biology has become an excuse for biotech startups’ indefinite approach to business in general. Most of the people involved expect some things to work eventually, but few want to commit to a specific company with the level of intensity necessary for success. It starts with the professors who often become part-time consultants instead of full-time employees—even for the biotech startups that begin from their own research. Then everyone else imitates the professors’ indefinite attitude. It’s easy for libertarians to claim that heavy regulation holds biotech back—and it does—but indefinite optimism may pose an even greater challenge for the future of biotech.

"Resistentialism" almost knows what a thing is. thx