Me on the Transit Zone and American economic policies

I joined Peter Clarke and Margo Kingston on their Transitzone podcast. Here's their own description of our discussion. You can also podcast it at their podcast channel or mine.

This last week of the election campaign has seen Donald Trump become even more overheated in his rhetoric. His fixation on whether Kamala Harris had a summer job working for McDonalds about 40 years ago, as she claims, has become a recurring feature of his rally rants. He has not relented an iota on the Springfield, Haitian attacks or his 2020, “rigged” election Big Lie, even as the voting machine company, Smartmatic, settles at the last minute a defamation case with far-right outlet NEWSMAX. Fox News is next in that litigation queue

But gradually, economic policies are coming into focus with Trump emphasising his across the board tariffs policy and 15% corporate tax offer to encourage manufacturing in the USA plus a grab bag of other throw it against the wall policy promises.

Kamala Harris delivered a major speech followed by a solo cable TV interview around HER economic policies. And yes, "opportunity economy" and ‘middle class” were repeated themes from her as you’d expect. There was some detail.

Peter Clarke, Margo Kingston with their guest, Nicholas Gruen, discuss the "competing" economic policies of Kamala Harris and Donald Trump (such as they are), with under 4o days to go to the USA election voting day on 5 November.

Alexis de Tocqueville is rudely awakened

Having recently made it to the United States to study American penitentiaries in 1831 Alexis de Tocqueville was woken by artillery fire and church bells. It was the 4th of July. He was particularly moved by the reading of the Declaration of Independence:

A profound silence reigned in the meeting. When in its eloquent plea Congress reviewed the injustices and tyranny of England we heard a murmur of indignation and anger circulate about us in the auditorium. When it appealed to the justice of its cause and expressed the generous resolution to succumb or free America, it seemed that an electric current made the hearts vibrate. This was not, I assure you, a theatrical performance. There was in the reading of these promises of independence so well kept, in this return of an entire people toward the memories of its birth, in this union of the present generation to that which is no longer, sharing for the moment all its generous passions, there was in all that something deeply felt and truly great.

Anyway, that was then.

Citizens doing it for themselves

(Defending democratic norms that is.)

Naturally enough the Republicans are misrepresenting an initiative to unpick their gerrymandering as something that will promote gerrymandering (sigh).

Liz Anderson from Crooked Timber waxes lyrical about citizen assemblies and makes the same point I’ve made. If you bundle citizens’ choices on democratic principle with their electricity prices or which party they barrack for, they won’t defend democratic principle. But if you constitute them to oversee democratic norms — they do that in a way that’s harder to corrupt than anyone appointed by government (for obvious reasons — if the government appoints putatively independent officers, they can appoint corrupt ones. See “Project 2025”.

I want to add … a more specific claim, which is the pivotal role citizens can play in directly strengthening the democratic structure of representative government. This can be seen in Michigan’s Independent Citizens’ Redistricting Commission. Unlike the many experiments in citizens’ assemblies that have only an advisory role, MICRC has genuine legislative power. It is charged with drawing fair (not gerrymandered) districts for the state legislature and Michigan’s seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, without interference by politicians.In 2018, voters passed an amendment to the state constitution proposed by the group Voters Not Politicians, which established the MICRC. The key argument for the amendment was straightforward and nonpartisan: politicians cannot be trusted to draw their own districts. When politicians draw the maps, they choose which voters get to vote for (or against) them, and choose the ones that will entrench their power. To empower voters to choose politicians instead of the other way around, voters need to be in charge of drawing the maps. The amendment passed with 61% of the vote, and took a majority in 67 of 83 counties–impossible without substantial support from voters of both parties.

According to the Brennan Center for Justice, many states’ efforts to end gerrymandering have failed because they gave politicians a say over the maps. The constitutional amendment establishing the MICRC addresses this problem by barring politicians, recent candidates, party officials, campaign consultants, lobbyists and others connected to such people from serving on the Commission. Only politically unconnected voters may serve. Another important feature of the MICRC is that, while Republicans and Democrats each get 30% of the seats, independent voters get the rest–a plurality. Holding these proportions fixed, and allowing each party in the state legislature to strike up to 20 applicants, the selection of commissioners is otherwise random. …

The process in Michigan was fraught. Commissioners engaged in long, heated arguments. Some broke down in tears over their conflicts.

Nevertheless, their output was clearly superior to letting politicians draw the maps. Michigan has been a basically 50-50 state for decades. Yet, before the MICRC was established, GOP politicians had blocked the Democratic party from taking both houses of the state legislature for 40 years, much of this time due to partisan gerrymandering. In 2016, the partisan vote for the Michigan House was almost exactly equal, yet Republicans won a 16-seat advantage in a 110-seat chamber. The MICRC, as directed by the state constitution, delivered maps that were not rigged in favor of either party. In 2022, with the help of its fair maps, voters delivered a Democratic sweep of both state legislative houses and all statewide offices. The maps were genuinely competitive for both parties: Democrats won the state legislature by only 2 seats in both houses. This election year, the GOP could easily win back their majority in both state houses.

Michigan’s success has inspired Ohio’s Citizens Not Politicians to get Issue 1 on the November ballot. Despite the fact that Ohio’s constitution already forbids partisan gerrymandering, the GOP officials who control the redistricting process have refused to comply with the law. In 2022 they got their way–despite losing two Ohio Supreme Court rulings declaring their maps unconstitutional–by running out the clock in Federal court. This time, a GOP-dominated ballot board approved ballot language that misleads voters by suggesting that Issue 1 means the opposite of what it actually says. And the GOP-dominated Ohio Supreme Court mostly went along with this wildly misleading language. Let’s hope Ohio’s voters see through this ruse. Last year, they rejected a 60% approval threshold for passing constitutional amendments, which they knew was designed to thwart their desire to protect abortion rights.

Where might citizens’ assemblies go from here? I suggest that the next step should be to empower them to legislate on voting rights as well as transparency and corruption in state government. These are also issues that politicians can’t be trusted to handle well. Citizens’ assemblies can strengthen the democratic character of representation as well as trust in representative government by reserving these issues for themselves.

Suppose these experiments are tried and succeed. A natural next step would be to empower the voters to establish a citizens’ assembly to legislate on any ordinary issue specified in a proposition, not just on democracy-reinforcing structures. The idea is that some issues may be too complex for a citizens’ initiative process. The issue may require considerable fact-finding, deliberation, and numerous tightly linked provisions. In such cases, voters cannot be expected to find the devils hiding in the details, especially if special interests have drafted and gathered the signatures for the initiative and are spending millions on misleading ads. I suspect that was a problem with California’s Prop 22, promoted by Uber and Lyft, which classified rideshare drivers as independent contractors without employee rights. (Alex Guerrero has some clever ideas on how to prevent corruption of single-issue citizens’ legislatures.)

The very possibility that voters could strip the state legislature of the power to legislate on a given issue and assign it to a citizens’ assembly might itself induce the representative legislature to behave more democratically–that is, to take the voters’ concerns more seriously. It’s one way to nudge our current laboratories of autocracy to behave more like laboratories of democracy.

Nicely put and might even be true

An ACE idea for our rent sodden economy

I’ve not checked this out carefully, and no doubt I’d have quibbles, but as Peter Martin points out, the basic logic of the Greens corporate tax grab aligns with the Henry Review’s fondness for allowing corporates to write off a the cost of equity like they currently write off their debt (allowance for corporate equity). In an amusing twist, the Business Council of Australia seemed to like the idea until their rent sodden members realised that, if the reform were made revenue neutral, a large number of them would pay much more tax — namely the miners, bankers and retailers. They all earn economic rents allowing them to make more money than is justified by their levels of investment. One thing you should do if you want to pursue this course is create some let-outs for super-normal profits that are the result of successful risk taking to innovate.

When the Greens proposed an extra super-profits tax on the excessive part of really excessive profits last week, business and the government acted as if the sky was about to fall in. …

Back in 2011, then Labor Treasurer Wayne Swan asked his business tax working group to consider it. … And before that, the Business Council of Australia itself put forward the idea in 2009 – known as an allowance for corporate equity – in its submission to the Henry Tax Review.

The council said the idea had “the potential to deliver significant benefits”.

At the heart of the Greens’ idea, as well as the idea put forward by the Business Council 15 years ago, is a two-tier system of company tax.

Ordinary profits would get taxed at a standard rate.

And here’s where the current Greens and the Business Council’s earlier idea start to diverge.

Under the Business Council proposal, the standard rate have been a rate of zero. Under the Green’s proposal this would be the present company tax rate. “Above normal returns” would get taxed at a higher rate.

What’s a normal return? Researchers at the ANU’s Tax and Transfer Institute, drawing on the experience of the countries that have done this, suggest using the 10-year government bond rate, which at the moment is close to 4%.

It would mean any annual profit in excess of (say) 4% of shareholders’ equity would be taxed at the higher rate, and the profit below that taxed at the lower rate.

The threshold proposed by the Greens is more generous. It’s that any profit in excess of the bond rate plus 5% would be taxed at the higher rate, meaning (at the moment) any profit in excess of 9% of shareholders’ equity.

The thinking behind the idea is that in a hypothetical perfectly competitive market, high returns on equity wouldn’t endure [because new entrants would compete away their margin].

But for some businesses in some industries, outsized returns are the norm. Among them are the big four banks, where the returns on equity exceed 10%.

For big mining companies such as Rio and BHP, those returns on equity approach 20%. With Coles and Woolworths, they exceed 25%.

In each, the profits aren’t whittled away by new entrants because it’s hard for new entrants to gain a foothold. …

So why not tax away just some of the well-above-normal profits that they’re earning in the absence of proper competition?

It’s an argument Swan used arguing for a resource super profits tax in 2010.

I remember this song topping the charts

It was a hit for Peter and Gordon and Peter was Peter Ascher — brother of Jane whom Paul McCartney was dating. He wrote it when he was 16 and didn’t think it was good enough for the Beatles. Seems good enough to me. Anyway, here’s his demo tape. And here’s an article I ran into about Paul and Jane now 81 and 78. Sic transit ….

Churchill’s country house Chartwell: proto-think-tank.

Quite the character. What a life!

Churchill … bought Chartwell in 1922 with the fruits of an inheritance. Much of the frenetic energy that he devoted over the next eighteen years to writing and journalism sprang from his need to pay for the house’s upkeep and for the generous entertaining that he undertook there.

It was during the 1930s that Chartwell mattered most. Churchill was out of office. He had a flat in London but no official residence and, for much of the time, no particular reason to be in the capital. Chartwell was not, though, a retreat from the world. It was a kind of factory, filled with secretaries and research assistants who hammered Churchill’s literary and political productions into shape. It was also a meeting place – close enough to London for people to come down for lunch, dinner or an evening of conspiracy. It was, to a large extent, at Chartwell that Churchill plotted his political campaigns of the decade. Two of these were misguided. He sought to resist the limited reforms that the Baldwin government proposed to British rule in India and to defend Edward VIII during the crisis that sprang from the king’s insistence on marrying an American divorcée. Another campaign he led from there – against the appeasement of Nazi Germany and in favour of British rearmament – would, in retrospect, be seen as the most important in interwar British politics.Churchill still had the best address book in Europe. Officials and ministers talked to him and sometimes provided him with confidential information. His country house was itself a huge advantage. Most upper-class weekends in the country meant a draughty bedroom, the certainty that breakfast (consisting of kedgeree) would be the least inedible meal of the day and the promise that conversation would be confined to hunting. Anyone who took refuge in the library would find nothing but bound copies of Punch. Those who came to see Churchill enjoyed a heated swimming pool and a generous supply of cold champagne. There was a superb library and a collection of maps that could be produced to explain any geopolitical crisis. Most of all, there was Churchill – exasperating and vain, but never dull.

Katherine Carter, a curator at Chartwell, puts the house and the people who gathered there at the centre of her book. The result is a stimulating and enjoyable work that shows us interwar politics from an unfamiliar angle. She traces an extraordinary series of guests. T E Lawrence, the kind of adventurer whom Churchill admired, turned up on his motorbike to talk about air power. Joseph Kennedy, the US ambassador in London and father of JFK, came down, though his pro-German views do not seem to have been much influenced by Churchill’s eloquence. The most unexpected guest was Ghanshyam Das Birla, a close associate of Gandhi who came to lunch in 1935 and who seems to have got on surprisingly well with Churchill. Carter does not give us the menu, though one assumes that even Churchill did not, on this occasion, indulge his taste for beef and beer.

As time went by, Churchill invited people who could tell him something about the state of Europe. They included Heinrich Brüning, chancellor of Germany between 1930 and 1932, and Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, a Czech of Austro-Hungarian and Japanese descent who talked to Churchill about how Europe might be unified. Although on the Right, Churchill increasingly recognised that allies against Hitler might be found on the Left. He understood that Stalin – unlike Trotsky, whom he despised – was a Russian nationalist, more interested in defending his own frontiers than spreading revolution abroad. This accounts for the hospitality extended to Ivan Maisky. The ally that mattered most to Churchill was France. He received Léon Blum, the socialist prime minister of the Popular Front government, and Pierre Cot, the minister of aviation, who was close to the Communist Party.

Chartwell went with a particular style of political action. Cut out of day-to-day policymaking, Churchill had the time to think big. His house functioned almost as an academic institution in which public figures came to spend brief sabbaticals. Churchill himself was simultaneously occupied with writing journalistic pieces about the state of the world and historical works (principally a biography of his ancestor the first Duke of Marlborough).

Paul Graham announces the existence of ‘founder mode’

How should you organise information flows in a company? No-one knows! What has Paul Graham uncovered here? My guess — and that’s all it is — is that at least for good founders’, there’s no way to ration their attention that can be decided on in principle. It needs to be decided on in situ. And who should be doing that deciding — that improvising about what they pay attention to and how they structure things in response? If they’re good, founders might be the best placed. And all the cookie cutter advice is just so much boilerplate.

At a YC event last week Brian Chesky gave a talk that everyone who was there will remember. Most founders I talked to afterward said it was the best they'd ever heard. …

The theme of Brian's talk was that the conventional wisdom about how to run larger companies is mistaken. As Airbnb grew, well-meaning people advised him that he had to run the company in a certain way for it to scale. Their advice could be optimistically summarized as "hire good people and give them room to do their jobs." He followed this advice and the results were disastrous. So he had to figure out a better way on his own, which he did partly by studying how Steve Jobs ran Apple. So far it seems to be working. Airbnb's free cash flow margin is now among the best in Silicon Valley.

The audience at this event included a lot of the most successful founders we've funded, and one after another said that the same thing had happened to them. They'd been given the same advice about how to run their companies as they grew, but instead of helping their companies, it had damaged them.

Why was everyone telling these founders the wrong thing? That was the big mystery to me. … In effect there are two different ways to run a company: founder mode and manager mode. Till now most people even in Silicon Valley have implicitly assumed that scaling a startup meant switching to manager mode. But we can infer the existence of another mode from the dismay of founders who've tried it, and the success of their attempts to escape from it. …

Hire good people and give them room to do their jobs. Sounds great when it's described that way, doesn't it? Except in practice, judging from the report of founder after founder, what this often turns out to mean is: hire professional fakers and let them drive the company into the ground.

One theme I noticed both in Brian's talk and when talking to founders afterward was the idea of being gaslit. Founders feel like they're being gaslit from both sides — by the people telling them they have to run their companies like managers, and by the people working for them when they do. Usually when everyone around you disagrees with you, your default assumption should be that you're mistaken. But this is one of the rare exceptions. VCs who haven't been founders themselves don't know how founders should run companies, and C-level execs, as a class, include some of the most skillful liars in the world.

Whatever founder mode consists of, it's pretty clear that it's going to break the principle that the CEO should engage with the company only via his or her direct reports. … Steve Jobs used to run an annual retreat for what he considered the 100 most important people at Apple, and these were not the 100 people highest on the org chart. … [A]nother prediction I'll make about founder mode is that once we figure out what it is, we'll find that a number of individual founders were already most of the way there — except that in doing what they did they were regarded by many as eccentric or worse.

Curiously enough it's an encouraging thought that we still know so little about founder mode. Look at what founders have achieved already, and yet they've achieved this against a headwind of bad advice. Imagine what they'll do once we can tell them how to run their companies like Steve Jobs instead of John Sculley.

Dan Davies considers founder mode

Dan Davies has a different interpretation. For those who’re interested I covered his terrific book on Stafford Beer here and recorded a discussion with him here.

Someone asked me what I thought about Paul Graham’s post from a couple of weeks ago on “founder mode”. The instinctive reaction is to groan and go something like “oh no, tech bros reinventing the wheel again”, but I think that would be a mistake for two reasons. First, in my experience Graham is considerably more thoughtful and interesting than the run of the mill for Silicon Valley.

And second, reinventing the wheel is underrated. … I’ve been fascinated by the fact that left to themselves in charge of something, intelligent people with an engineering background will always seem to independently come up with something that looks quite like Stafford Beer’s cybernetics. … As well as being intrinsically interesting, it makes me always want to read this sort of thing, because I think it might be important to get a handle on which bits of management cybernetics people tend to reinvent, because that’s likely to say something about what’s important or correct about the theory.

“[F]ounder mode” really is talking about the same things that Stafford Beer was, because its central point is exactly the one that’s the subject of “Diagnosing The System” – that there is no reason at all to believe that the best way to design a system of information flows and allocate bandwidth will produce something which looks like a normal org chart. And even less reason to believe that the relationship between the org chart and the correct information design will be stable at different moments in time.

A lot of people who read the “founder mode” essay seemed to latch on to the idea that it’s a justification for micromanagement, based on this passage:

“Hire good people and give them room to do their jobs. Sounds great when it's described that way, doesn't it? Except in practice, judging from the report of founder after founder, what this often turns out to mean is: hire professional fakers and let them drive the company into the ground.”

I admit, this does look pretty much like an apologia for micromanagement. But if we ignore the drive-by at “professional fakers” (which I doubt are more common in tech than other industries), then let’s compare it to this passage:

“Complex organisations … need to be aroused when a threat to their survival appears and to recognize quickly when a desired state has been reached. Too often, however, the non-routine channels for such information in a large organisation are inadequate or non-existent and indications of danger are filtered out rather than amplified. Management must design non-routine channels so that it may act on non-routine information in time to avert disaster or seize opportunity”.

This is from Allenna Leonard’s “Cybernetic Glossary”, at the back of Vanilla Beer’s wonderful biography of Stafford Beer. It’s part of the discussion of what the jargon calls “algedonic signals”. These are low-frequency, high-priority messages which bypass the usual channels to direct signals from the immediate environment to the level of organisation at which the system itself can be redesigned. (My go-to example is the red handle in a train driver’s cabin, which not only physically stops the train, but has an organisational role in beginning a process of rewriting the timetable for that day).

I think “founder mode” is partly a rediscovery of the need for this kind of thing. “Founders” don’t really go around suddenly jumping into operational tasks at random for the joy of nitpicking; they do things when they think that they have new information that requires them to get involved.

And, of course, in order to identify what information has the red-handle property, you have to know what the purpose of the company is – “purpose” in this sense meaning “the criterion of what makes something relevant to the company”. That’s why Graham identifies it with foundership – in context this means someone who has the right to decide the purpose, and therefore occupies the right spot in the information processing system.

But I think it’s a position in the system rather than a unique property of start up guys; my go-to-example here would be John Birt, who didn’t create the BBC, but who was in the right position to take two pieces of information (“this internet thing has arrived” and “the BBC can no longer count on license fee growth”) and turn them into a pretty radical set of organisational changes. …

Although Paul Graham is correct to say “There are as far as I know no books specifically about founder mode”, I’d argue that there are a few very good books on general principles of information engineering, which have founder mode as one of their special cases. There’s a list of them in the back of my book if he doesn’t mind paying academic prices.

A strange, intriguing TV event

Oswald Mosely defends himself in late 1967 in an interview with David Frost. Then the audience got to yell at him. I doubt it was unjust to Mosely, but the format was less edifying than it might have been.

Accidental anti-semitism

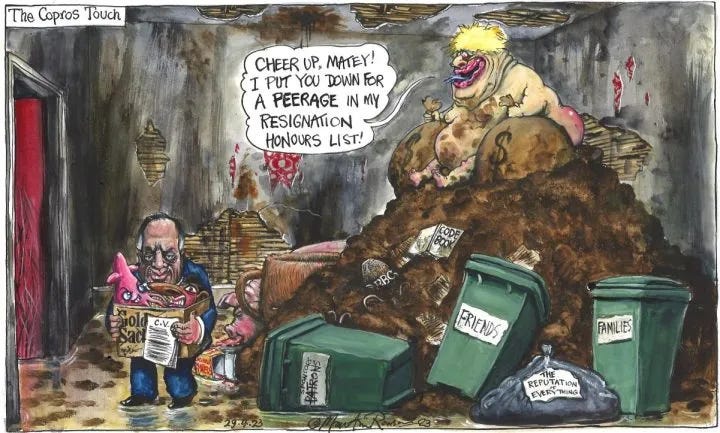

I copied the cartoon above by Martin Rowson for inclusion in this newsletter before I realised it was there not for the reason I reproduced it. My eye was drawn to Boris sitting on the pile of compost that was his prime ministership. But it was the picture on the left that caused all the fuss. Spectator editor Fraser Nelson takes up the story (In May last year).

Being a cartoonist is a high-risk job nowadays. Your job is to satirise and caricature, to exaggerate bodily features. … If someone has a prominent feature, then you exaggerate the feature. It’s the way cartooning works. If the subject has slightly big ears, you make them massive – as we have for the King in our coming coronation cover. It’s comic, teasing and, yes, sometimes brutal. But if you do this to a religious figure or an ethnic minority, you can be easily accused of bigotry. As the Guardian has just found out.

Rowson made an honest mistake, but he’s no anti-Semite – and no one is pretending otherwise

I had no idea that Richard Sharp, who last week quit as BBC chairman, is Jewish. … The idea that anyone at this newspaper was cackling at an anti-Semitic joke is plainly absurd: they will be as horrified as Rowson now is at this simple, explainable and tragic mistake.

So why was it drawn that way? Sharp used to be Rishi Sunak’s boss at Goldman Sachs – which is why Rowson added a Goldman Sachs-branded box in the illustration, with a miniature Sunak inside it. The bank was famously derided as an omnipresent ‘vampire squid sucking the face of humanity’ (a famous reference Guardian readers know and love) which is why Rowson depicted a squid in a box Sharp is carrying. Sharp is stonkingly rich and helped to arrange an £800,000 loan for Boris Johnson but failed to properly disclose that when Johnson made him BBC chairman. Should Sharp have disclosed this to the parliamentary committee? Of course. His failure to do so led to his resignation.

All this is rich material for any satirist, especially one on the left. So Rowson depicted all of this in a cartoon (above) in which Sharp’s face is a tiny part. It’s not a sympathetic portrayal: he looks like a venal millionaire, which is consistent with the Guardian’s line and Rowson’s oeuvre. …

As an editor of a magazine that runs humour and satire, I’ve been through similar storms over the years. Cartoons can now cause more controversy than any story. … Twitter storms tend to have five stages. 1) General, often confected outrage 2) Someone in public office joins in, making it a reportable news story 3) The target can make the mistake of responding, either with a statement or by removing the offending joke/cartoon, thinking it will relieve rather than add pressure 4) A resignation hunt then starts – especially if a publication’s staff join in the attack until 5) Someone is fired, to assuage the mob, usually because the commercial people (who have less stomach for fights) say it’s damaging business.

At The Spectator, we’re lucky. We’re family-owned, so don’t have woke shareholders worrying about their Twitter feeds. When advertisers were persuaded by Twitter trolls to boycott us due to a Matthew Parris article on trans issues, Andrew Neil banned the advertiser. I often think of the protection that the model of family ownership offers against such forces: what publication, anywhere, has actually banned advertisers?

[W]hat’s odd, with the Rowson row, is seeing those who normally abhor cancel culture getting stuck in now that the victim is the Guardian. Yes, this fraction of this cartoon can be made to look very bad if cropped in a certain way – but does anyone seriously, genuinely believe that Rowson was motivated by anti-Semitism? Or think that the squid he drew was not the ‘vampire squid’ of lore but in fact a cunning, dog-whistle reference to a notorious Nazi squid cartoon from 1938? …

He’ll feel awful about this. Any cartoonist would. He has become the latest victim of a trend in digital life where cartoonists are flayed, apologies are not accepted and forgiveness is not offered. No one who cares about satire and its role in our public debate should draw any satisfaction from the storm he now finds himself in.

Fellow Guardian cartoonist remained unimpressed:

“You pitch three ideas ... It will have to go through quite a stringent editing process before they choose it, so in relation to Martin Rowson I’m curious about how that happened, how the cartoon got through.”

Dark photos from a tweet

Ukraine is Losing the War

John Ganz on Ukraine.

Two and a half years from Russia’s invasion, Ukraine today is facing an increasingly dire situation. In the east of the country, costly Russian offensives are making steady gains. Russian strikes have also badly damaged Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, making for a long, hard winter for Ukrainian civilians already weary of the war. Ukraine is also having trouble mobilizing more young men to fight: many are going into exile or hiding to avoid the war. In a recent interview with the New Yorker, President Volodymyr Zelensky basically admitted that the Ukrainian incursion into Russian territory near Kursk was an almost desperate gambit, without a long-term strategic concept, in the face of a relentless onslaught:

…it was clear to us that Russia is pressing us in the east. No matter how the Kursk operation ends, military analysts will someday calculate the speed of Russia’s progress and ask, What prevented us from stopping them earlier? How fast were they moving in the east before the Kursk operation began, and why? Ukraine had trouble mobilizing people, they might say, and didn’t have enough strength to stop them, but that is diverting the focus from the more pertinent point—namely, the fact that we should receive what we’ve been promised. I say, first give it to us, and then analyze if the root of the problem is with Ukraine or with you.

Imagine: you’re struggling in a tough war, you’re not receiving aid, you strain to maintain morale. And the Russians have the initiative in the east, they have taken parts of the Kharkiv region, and they’re about to attack Sumy. You have to do something—something other than endlessly asking your partners for help. So what do you do? Do you tell your people, “Dear Ukrainians, in two weeks, eastern Ukraine will cease to exist”? Sure, you can do that, throw up your hands, but you can also try taking a bold step. … Already, our fighters in the east say that they are being battered less frequently. …

With less men and materiel than Russia, Ukraine’s options are limited. It seems highly likely that they will have to sacrifice territory in any prospective negotiation. … The best case scenario that I can see, far short of victory according to some on the Ukrainian side, is that Zelensky’s plan includes a way to give Russia another bloody nose, making peace negotiations somewhat more favorable to the Ukrainian side and making the sacrifices of this terrible war bearable for the Ukrainian people. Withstanding the Russian invasion in the first place was a heroic feat that rightly earned the world’s admiration: it’s already a great victory in its own right. It would be a tragedy indeed to see that accomplishment squandered by either a lack of hope or a lack of realism.

Archie Bunker: sitcom character

The Unintended Consequences of Merit-based Teacher Selection: Evidence from Large-scale Reform in Colombia, Matias Busso, Sebastián Montaño, Juan S. Muñoz-Morales, and Nolan G. Pope

Teacher quality is a key factor in improving student academic achievement. As such, educational policymakers strive to design systems to hire the most effective teachers. This paper examines the effects of a national policy reform in Colombia that established a merit-based teacher-hiring system intended to enhance teacher quality and improve student learning. Implemented in 2005 for all public schools, the policy ties teacher-hiring decisions to candidates’ performance on an exam evaluating subject-specific knowledge and teaching aptitude. The implementation of the policy led to many experienced contract teachers being replaced by high exam-performing novice teachers. We find that though the policy sharply increased pre-college test scores of teachers, it also decreased the overall stock of teacher experience and led to sharp decreases in students’ exam performance and educational attainment. Using a difference-in-differences strategy to compare the outcomes of students from public and private schools over two decades, we show that the hiring reform decreased students’ performance on high school exit exams by 8 percent of a standard deviation, and reduced the likelihood that students enroll in and graduate from college by more than 10 percent. The results underscore that relying exclusively on specific ex ante measures of teacher quality to screen candidates, particularly at the expense of teacher experience, may unintentionally reduce students’ learning gains.

Heaviosity half-hour

G.K Chesterton discovers South Wales (thinking he’s discovered New South Wales)

Not that it’s particularly heavy, but I enjoyed Chesterton’s introduction to his book Orthodoxy.

THE only possible excuse for this book is that it is an answer to a challenge. Even a bad shot is dignified when he accepts a duel. When some time ago I published a series of hasty but sincere papers, under the name of "Heretics," several critics for whose intellect I have a warm respect (I may mention specially Mr. G. S. Street) said that it was all very well for me to tell everybody to affirm his cosmic theory, but that I had carefully avoided supporting my precepts with example. "I will begin to worry about my philosophy," said Mr. Street, "when Mr. Chesterton has given us his." It was perhaps an incautious suggestion to make to a person only too ready to write books upon the feeblest provocation. But after all, though Mr. Street has inspired and created this book, he need not read it. If he does read it, he will find that in its pages I have attempted in a vague and personal way, in a set of mental pictures rather than in a series of deductions, to state the philosophy in which I have come to believe. I will not call it my philosophy; for I did not make it. God and humanity made it; and it made me.

I have often had a fancy for writing a romance about an English yachtsman who slightly miscalculated his course and discovered England under the impression that it was a new island in the South Seas. I always find, however, that I am either too busy or too lazy to write this fine work, so I may as well give it away for the purposes of philosophical illustration. There will probably be a general impression that the man who landed (armed to the teeth and talking by signs) to plant the British flag on that barbaric temple which turned out to be the Pavilion at Brighton, felt rather a fool. I am not here concerned to deny that he looked a fool. But if you imagine that he felt a fool, or at any rate that the sense of folly was his sole or his dominant emotion, then you have not studied with sufficient delicacy the rich romantic nature of the hero of this tale. His mistake was really a most enviable mistake; and he knew it, if he was the man I take him for. What could be more delightful than to have in the same few minutes all the fascinating terrors of going abroad combined with all the humane security of coming home again? What could be better than to have all the fun of discovering South Africa without the disgusting necessity of landing there? What could be more glorious than to brace one's self up to discover New South Wales and then realize, with a gush of happy tears, that it was really old South Wales. This at least seems to me the main problem for philosophers, and is in a manner the main problem of this book. How can we contrive to be at once astonished at the world and yet at home in it? How can this queer cosmic town, with its many-legged citizens, with its monstrous and ancient lamps, how can this world give us at once the fascination of a strange town and the comfort and honour of being our own town?

To show that a faith or a philosophy is true from every standpoint would be too big an undertaking even for a much bigger book than this; it is necessary to follow one path of argument; and this is the path that I here propose to follow. I wish to set forth my faith as particularly answering this double spiritual need, the need for that mixture of the familiar and the unfamiliar which Christendom has rightly named romance. For the very word "romance" has in it the mystery and ancient meaning of Rome. Any one setting out to dispute anything ought always to begin by saying what he does not dispute. Beyond stating what he proposes to prove he should always state what he does not propose to prove. The thing I do not propose to prove, the thing I propose to take as common ground between myself and any average reader, is this desirability of an active and imaginative life, picturesque and full of a poetical curiosity, a life such as western man at any rate always seems to have desired. If a man says that extinction is better than existence or blank existence better than variety and adventure, then he is not one of the ordinary people to whom I am talking. If a man prefers nothing I can give him nothing. But nearly all people I have ever met in this western society in which I live would agree to the general proposition that we need this life of practical romance; the combination of something that is strange with something that is secure. We need so to view the world as to combine an idea of wonder and an idea of welcome. We need to be happy in this wonderland without once being merely comfortable. It is THIS achievement of my creed that I shall chiefly pursue in these pages.

But I have a peculiar reason for mentioning the man in a yacht, who discovered England. For I am that man in a yacht. I discovered England. I do not see how this book can avoid being egotistical; and I do not quite see (to tell the truth) how it can avoid being dull. Dulness will, however, free me from the charge which I most lament; the charge of being flippant. Mere light sophistry is the thing that I happen to despise most of all things, and it is perhaps a wholesome fact that this is the thing of which I am generally accused. I know nothing so contemptible as a mere paradox; a mere ingenious defence of the indefensible. If it were true (as has been said) that Mr. Bernard Shaw lived upon paradox, then he ought to be a mere common millionaire; for a man of his mental activity could invent a sophistry every six minutes. It is as easy as lying; because it is lying. The truth is, of course, that Mr. Shaw is cruelly hampered by the fact that he cannot tell any lie unless he thinks it is the truth. I find myself under the same intolerable bondage. I never in my life said anything merely because I thought it funny; though of course, I have had ordinary human vainglory, and may have thought it funny because I had said it. It is one thing to describe an interview with a gorgon or a griffin, a creature who does not exist. It is another thing to discover that the rhinoceros does exist and then take pleasure in the fact that he looks as if he didn't. One searches for truth, but it may be that one pursues instinctively the more extraordinary truths. And I offer this book with the heartiest sentiments to all the jolly people who hate what I write, and regard it (very justly, for all I know), as a piece of poor clowning or a single tiresome joke.

For if this book is a joke it is a joke against me. I am the man who with the utmost daring discovered what had been discovered before. If there is an element of farce in what follows, the farce is at my own expense; for this book explains how I fancied I was the first to set foot in Brighton and then found I was the last. It recounts my elephantine adventures in pursuit of the obvious. No one can think my case more ludicrous than I think it myself; no reader can accuse me here of trying to make a fool of him: I am the fool of this story, and no rebel shall hurl me from my throne. I freely confess all the idiotic ambitions of the end of the nineteenth century. I did, like all other solemn little boys, try to be in advance of the age. Like them I tried to be some ten minutes in advance of the truth. And I found that I was eighteen hundred years behind it. I did strain my voice with a painfully juvenile exaggeration in uttering my truths. And I was punished in the fittest and funniest way, for I have kept my truths: but I have discovered, not that they were not truths, but simply that they were not mine. When I fancied that I stood alone I was really in the ridiculous position of being backed up by all Christendom. It may be, Heaven forgive me, that I did try to be original; but I only succeeded in inventing all by myself an inferior copy of the existing traditions of civilized religion. The man from the yacht thought he was the first to find England; I thought I was the first to find Europe. I did try to found a heresy of my own; and when I had put the last touches to it, I discovered that it was orthodoxy.

It may be that somebody will be entertained by the account of this happy fiasco. It might amuse a friend or an enemy to read how I gradually learnt from the truth of some stray legend or from the falsehood of some dominant philosophy, things that I might have learnt from my catechism—if I had ever learnt it. There may or may not be some entertainment in reading how I found at last in an anarchist club or a Babylonian temple what I might have found in the nearest parish church. If any one is entertained by learning how the flowers of the field or the phrases in an omnibus, the accidents of politics or the pains of youth came together in a certain order to produce a certain conviction of Christian orthodoxy, he may possibly read this book. But there is in everything a reasonable division of labour. I have written the book, and nothing on earth would induce me to read it.

I add one purely pedantic note which comes, as a note naturally should, at the beginning of the book. These essays are concerned only to discuss the actual fact that the central Christian theology (sufficiently summarized in the Apostles' Creed) is the best root of energy and sound ethics. They are not intended to discuss the very fascinating but quite different question of what is the present seat of authority for the proclamation of that creed. When the word "orthodoxy" is used here it means the Apostles' Creed, as understood by everybody calling himself Christian until a very short time ago and the general historic conduct of those who held such a creed. I have been forced by mere space to confine myself to what I have got from this creed; I do not touch the matter much disputed among modern Christians, of where we ourselves got it. This is not an ecclesiastical treatise but a sort of slovenly autobiography. But if any one wants my opinions about the actual nature of the authority, Mr. G. S. Street has only to throw me another challenge, and I will write him another book.