Kilkenomics edition

And some other things including the BBC fiasco and post-liberalism

In this video I show how the basic analysis introduced in earlier videos applies to democracy. Put simply, because politicians are also ultimately in charge of the rules of the game they compete in, they’re constantly tempted to bend or even break those rules.

This video looks at the safeguards the US founding fathers built in, why they are failing, and how other parliamentary democracies in the UK, Australia, and Canada are more vulnerable than you might think.

But there is good news. A powerful new democratic settlement is in sight, taking the job of defending our norms away from the elites and giving it back to the people. We investigate the new institutions that could save democracy from itself.

Please click through and #LikeShareAndSaveTheWorld.

And because this is the Kilkenomics edition of my newsletter, and in case you don’t know, each of the videos is accompanied by an interview of about 20 minutes with Irish comedian and general Good Guy Colm O’Regan. As ever, you can see the website of the videos here.

Kilkenomics: 2025

A review that popped up in my notifications owing to a nice comment someone made about me. Clearly a man of taste and distinction.

For years I’ve listened to the David McWilliams Podcast, both episodes, every week. It’s a rare mix of economic insight and human storytelling, part anthropology, part history lesson, part pub chat. What I’ve always loved about it is how easily it moves between the big and the small, from Irish house prices to global politics, from the economics of Taylor Swift to the psychology of inflation...

So for as long as I’ve been tuning in, I’ve wanted to go to Kilkenomics, the festival McWilliams co-founded with comedian Richard Cook back around 2010, at the tail end of the economic crash that hit Ireland particularly hard. The idea was mischievous and brilliant though, taking the world’s driest subject … economics … and make it funny. Not by dumbing it down, but by pairing economists with stand-up comedians who would force them to explain their ideas in simple language and defend them with humour.

It could only have started in Ireland, and it could only really work in a place like Kilkenny rather than Dublin...

Economics without the ego

Over three days, I found myself bouncing between pubs and venues, drifting from one kind of brilliance to another. Dylan Moran, one of my favourite comedians, chaired a session on “Putin’s Next Move?”, turning geopolitics into something both terrifying and hilarious...

[T]he “Bad Ideas from Dead Economists” session featuring Nicholas Gruen was a highlight; a reminder that the world’s worst ideas rarely die, they just come back wearing different suits.

But it wasn’t all doom and data. There was a city tour led by Karl Spain, which got people moving, mingling and pondering what might have been a bit of a porky. Then “Reasons to Be Cheerful” closed things on a high, a necessary reminder that optimism is not naïve; it’s a civic responsibility and very necessary when smart people have a habit of being cynical and negative...

The living room city

Between sessions, you end up doing what Kilkenny makes easiest … talking. Every pub becomes a salon of sorts. The pint of Guinness, at €6.30 or €7, is still the city’s price of admission, though increasingly more people are drinking Guinness 0.0, a small but telling sign of changing habits.

The pubs aren’t just drinking holes here; they’re the city’s living rooms. That’s where Kilkenomics actually happens, in the laughter between strangers, the disagreements over housing policy and the moment someone decides to buy another pint rather than end the debate...

The anatomy of a Challenger City

That’s what fascinates me most about Kilkenny; its ability to host something as globally relevant as Kilkenomics without trying to be anything other than itself. It’s not trying to become Dublin, but it is attracting Dubliners. It’s not building a tech cluster, more building a culture of curiosity.

In a world full of sterile conferences and self-congratulatory panels, Kilkenomics works because it’s alive, held in venues that smell of Guinness, in a city that knows how to laugh and with people who still believe ideas can change things. It’s intellectual life that doesn’t feel like homework.

If there’s a lesson here for other small cities … in Canada, the US, the UK … it’s stop saying you can’t. Stop waiting for scale, stop envying the capitals and start creating your own stage. Kilkenny didn’t invent something completely new; it combined two things that didn’t belong together and made them work. Comedy and economics, intellect and mischief, local and global...

Kilkenny may be small, but for one long weekend every year, it’s the smartest city in the world.

To being Challengers.

Irish comedy

A highlight of Kilkenomics for me is the dinner for friends, family and remaining members of the repertory group that are Kilkenomics regulars on the Sunday night after all the shows have finished. There I sat next to Irish comedian Barry Murphy fresh from the last session of the festival which he compared (and I was a panelist). He was simply hilarious and the highlight of the festival. Nothing is recorded at Kilkenomics so I can’t show it to you, but you can check out this video of him for a bit of at taste. Anyway we swapped favourite comedy sketches - I mentioned John Clarke to him and he was unaware of him and he sent me the piece below.

He asked me if I knew of Stuart Lee and I told him he was my favourite practicing comedian and mentioned his Brexit set which I find just hilarious.

The American turn to stablecoins

I’ve been staying with my friend Felix Martin in London while he wrote this column - which draws on his PhD on dollarisation.

The White House argues that US dollar stablecoins will entrench the supremacy of the greenback, plug the US’s fiscal deficit, and enable the Fed to cut rates. Yet the history of dollarisation suggests that the administration’s plans to profit from extraterritorial seignorage will meet stiff resistance. It is even possible that the project finally incentivises the global adoption of a genuine supranational currency eight decades after John Maynard Keynes first floated the idea.

On February 4, barely two weeks after U.S. President Donald Trump’s second inauguration, newly appointed White House artificial intelligence and crypto czar David Sacks explained why the new administration was going all-in on stablecoins. Privately-issued, dollar-backed digital tokens, he explained, “have the potential to ensure American dollar dominance internationally, to increase the usage of the US dollar digitally as the world’s reserve currency, and in the process create potentially trillions of dollars of demand for US treasuries, which could lower long-term interest rates.” The reality, however, may be very different...

Stephen Miran, Trump’s recent Federal Reserve board appointee, claimed in a speech last week that recent U.S. legislation changes the game not just for the Department of the Treasury but for the US Federal Reserve as well. He points out that the widespread adoption of dollar stablecoins by foreign residents will result not just in a convenient new source of funding for the budget deficit, but an explosive new gusher of capital inflows to the economy too. A “global stablecoin glut”, analogous to the famous global savings glut identified by former Fed Chair Fed Ben Bernanke in 2005, will inundate the U.S. balance of payments with a rush of foreign money...

Miran predicts that the effect will not be trivial. The Fed itself forecasts that stablecoin demand may hit $3 trillion by 2030, compared with outstanding dollar-denominated digital tokens of about $300 billion right now, according to CoinGecko. The 2030 forecast is not far off the total quantity of U.S. Treasury securities that the central bank bought under its pandemic-era quantitative easing programme...

Stablecoins are new. Dollarisation, however, is not. There is a long history of other countries using the greenback for savings and payments, in the form of either hard cash or bank deposits. Many examples from the pre-stablecoin era certainly corroborate Miran’s claim that dollarisation has significant consequences for macroeconomic policy. Yet the history also suggests an important reason why America’s stablecoin power-play might not pan out as he predicts.

The basic problem is that for every benefit to Uncle Sam, the global propagation of US dollar usage brings an equal and opposite cost to the countries whose financial systems are being dollarized. These costs can be much larger, relative to the size of individual foreign economies, than the positive effects for the U.S...

As a result, dollarisation has historically been far from a one-way bet. Instead, it has ebbed and flowed with the capacity of foreign governments to resist it. In the 1980s and 90s, high inflation and volatile exchange rates made the use of the greenback an attractive option for businesses and households in poorer economies...

Yet the uncomfortable constraints generated a countervailing response. Policies and institutions improved in heavily dollarised economies. Governments made central banks independent, which helped to tame inflation, while also liberalising financial markets and consolidating their public finances. Except in the cases of a few well-known macroeconomic miscreants such as Turkey and Argentina, the incentives to use US dollars instead of the domestic currency therefore steeply declined. A recent comprehensive survey looked at countries that had more than 10% of their bank deposits dollarized in 2000. In more than two-thirds of those cases, dollarisation subsided over the following two decades – often dramatically so...

These historical dynamics hold a basic lesson. The incentives for the rest of the world to resist the loss of monetary sovereignty are very large. If other countries are proactive in ensuring that their own payments and financial systems remain competitive, and their public finances sustainable, the barriers to colonisation by the greenback are likely to be high. In other words, digital dollarisation risks the same fate as the analogue sort, rendering Miran’s dreams of easy money without any inflationary payback as unattainable as ever.

A scenario still more nightmarish for the U.S. is also possible. The Trump administration’s bid for stablecoin supremacy might not just fail, but backfire...

Ever since the birth of the modern international monetary system at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, other countries have rankled at having to use the US dollar as the de facto international currency. Yet they have never managed to agree a viable alternative. British economist John Maynard Keynes proposed a genuinely supranational currency – the bancor – managed by a multilateral cooperative, but the idea was swiftly nixed by the U.S...

That might be about to change. The undisputed value of monetary sovereignty means that the rest of the world has always had a motive for killing off the U.S. dollar’s global dominance. The IMF’s SDR plausibly supplies the means. The overt U.S. pursuit of a global stablecoin glut may now create the opportunity. The dollar’s date with destiny may finally be at hand.

Kind of intriguing

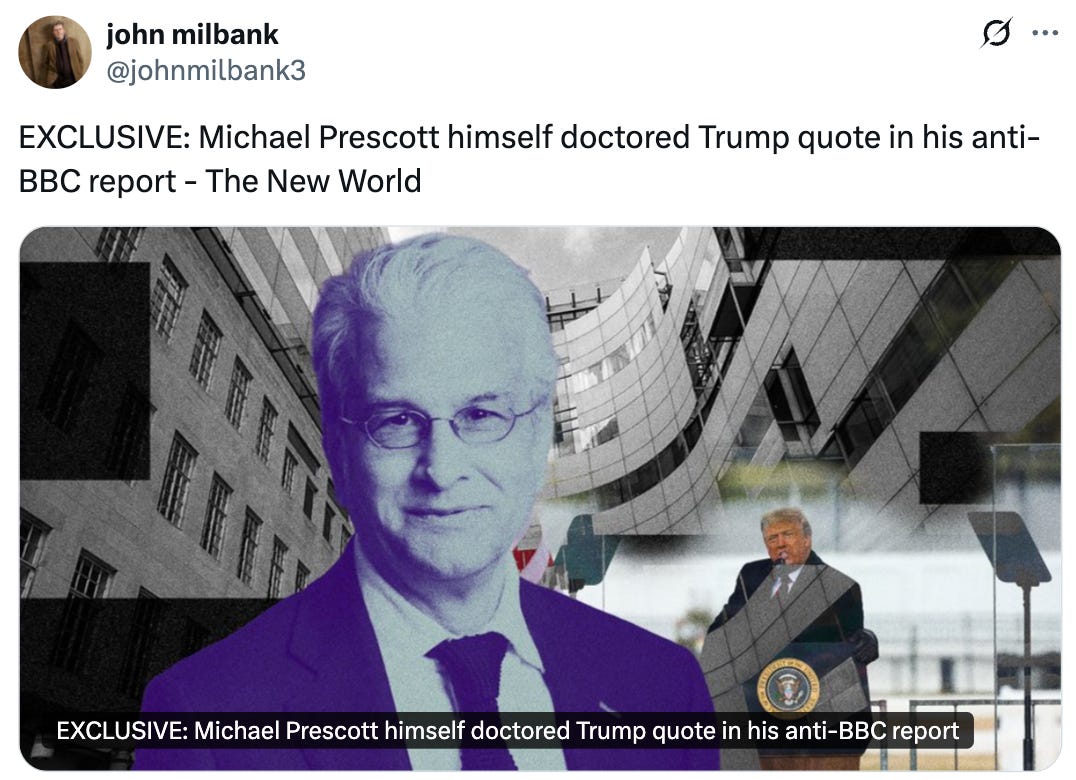

Excitement at the BBC

The Brits are always resigning. I saw the hit-job on the BBC courtesy of some right wing station and thought two things. 1) Of course editing Trump’s speech like that was completely beyond the pale. 2) It was pretty much standard operating procedure across the whole of the media both right and left, high and low brow. Indeed it exemplified by nothing more than the sneering low brow right journo who was introducing it. In fact, the hit piece itself edited Trump’s speech unfairly spinning it the other way.

So things are pretty dire at this stage. This piece which is unpaywalled from Quillette was good at depicting the rot - and it wasn’t ‘post-modernism’ what done it. It was modernism. And though it comes from a right of centre perspective, I’m thinking - or perhaps it’s better to say an anti-left perspective - it’s not overly partisan. The worst thing about it is that is glosses over ‘he-said-she-said’ journalism as appropriate, which it obviously isn’t if it comes down to “experts differ on shape of earth, flat or round: you be the judge”.

For the past two weeks, news in the UK has been dominated by the news itself, as the country’s public-service broadcaster has been consumed by controversy. On 3 November, the Daily Telegraph began reporting on the contents of an internal memo it had seen that contained scandalous evidence of bias and dishonest reporting at the BBC. ...

In an interview with GB News the day after the contents of the memo were first reported by the Telegraph, Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch declared that “heads should roll.” Finally, on 9 November, they did when director general of the BBC, Tim Davie, and the CEO of news, Deborah Turness, both resigned. ...

As a former BBC journalist who now teaches journalism at university, I can tell you that, no, the BBC’s journalism is not impartial, and yes, the corporation is institutionally biased.

... The BBC was not always like this—the roots of the current crisis can be traced to developments at the corporation during the 1990s. ...

Victorian Journalism

A BBC journalist who arrived from 1955 in a time machine would likely be horrified by the state of BBC journalism in 2025. This doesn’t mean that all journalists in the past were truthful—they weren’t. But they understood that their principal goal was to try to tell the truth as best they could, and this pursuit of truth was structurally protected. ...

The Rise of Boomer Journalism

There was, however, a problem with classical Victorian journalism: it tended to be dry and dull. ... The Boomers craved excitement in an era of unprecedented peace and affluence, and they came of age during an unashamedly idealistic and utopian decade of cultural rebellion. ...

John Birt’s Mission to Explain

After he assumed the job of BBC director general, Birt lost no time in declaring war on classical Victorian journalism and all those who practised it. He named this project the “Mission to Explain,” the strategic objective of which was ending the separation of fact and opinion. ...

Narrative construction and management became the most important journalistic skills. Born reports that older journalists complained of “Stalinist pressures to take the ‘BBC line’ editorially.” ...

As a consequence of these developments, modern BBC journalism now suffers from two major defects. The first of these is the reliance on narrative. ... The BBC’s second major defect is that the need to protect the narrative pushes truth-telling into second place. ...

The real problem for the BBC is that it is held captive by a Royal Charter that obliges it to be impartial when it is not. One solution, therefore, would be to scrap the Charter and allow the BBC to be as openly opinionated and biased as any other broadcaster. ...

Who’da thunk experts would know more than the Brexit Bus?

The relevant paper is here.

Alasdair MacIntyre: Postliberalism’s Reluctant Godfather

This article had me reading a fair bit about post-liberalism. I think it’s a bit of a non-starter myself, but then one of its major progenitors turns out to be Alasdair MacIntyre who I’m a big fan of. Anyway, this is an excellent article by an excellent writer. He works for a think tank that’s basically pro-Trump which is enough to give me hebes, but his scholarship, or what I’ve seen of it, does not put its thumb on the scales. MacIntyre would have been appalled by Trump. Beneath this article I reproduce a piece on post-liberalism from a left of centre perspective.

Alasdair MacIntyre (1929-2025) had all the signs of a restless mind. Few philosophers changed their views as much as he did. Thomas Kuhn, in The Structure of Scientific Revolution, described how difficult it is to move from one intellectual paradigm to another. But the truly difficult task is to reflect on one’s failure in accepting the old paradigm, and to give an account of it.

That’s the lonely, humbling task MacIntyre set for himself in the 1970s. Like many of his generation, his paradigm had been Marxism. Born in 1929 in Glasgow, MacIntyre had joined the thriving British postwar left, blending his philosophical pursuits with political activism. ...

By the late 1970s, MacIntyre had come up with what was for a British-educated, revolution-endorsing philosopher a stunning answer: Aristotle. More than just invoking a long dead thinker as an authority, MacIntyre asserted that Aristotle succeeded in providing coherent answers where Marxism and liberalism had failed.

“Aristotle succeeded in providing coherent answers where Marxism and liberalism had failed.”

In After Virtue (1981), MacIntyre outlined the core theses of this Aristotelian paradigm. The pursuit of the good had to be exercised in a social context. Moral philosophy, he wrote, “characteristically presupposes a sociology.” Human beings discover the good together, in practice-based communities, by cultivating in common the qualities of mind and character—the virtues—necessary to achieve the good. ...

We ended up in this position, MacIntyre argues, because of modern liberal individualism, which defines the human being as essentially constituted by his autonomy. It assumes an individualist society of autonomous agents, and the moral theory it tries to build upon that assumption is one whereby a human being legislates moral rules for himself as the moral law. This idea—a Kantian one—stems from the Enlightenment project. ...

MacIntyre grasped the irresolvable character of our social conflict while most Westerners were still convinced that we could rediscover some elusive political or economic consensus. MacIntyre explained why that aspiration, so dear to the postwar world, was now impossible. ...

“We’re dumber than we think we are because we’ve lost more than we realize.”

MacIntyre was easily one of the most brilliant philosophers the British Isles produced in the 20th century. But his reputation within academic philosophy did not match his achievements. Martha Nussbaum took to the New York Review of Books to denounce MacIntyre’s revolt from reason. ...

The most enthusiastic audience for continuing MacIntyre’s tradition of inquiry came from the American right. Like Hegel, MacIntyre spawned a left-wing school and a right-wing school; as with Hegel, one school is poised to be far more influential than the other. Politics was his weak point, as Pierre Manent observed. ... In 2004, MacIntyre argued that one should not vote for either American political party. ...

“It is impossible to understand the new postliberal right without discussing Alasdair MacIntyre.”

There is, to be sure, considerable theoretical distance between MacIntyre himself and these postliberals. MacIntyre himself also tried to put as much personal distance between him and those rightists as he could, such as in his pronounced refusal to read Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option. In short, MacIntyre begat devoted children that he disowned. Whether he was right to do so is a question that MacIntyre’s death does not answer. Nor should it. He helped us see the ruins of our time. What practices we develop to escape them is no longer his concern. These questions trouble us; he can rest in peace.

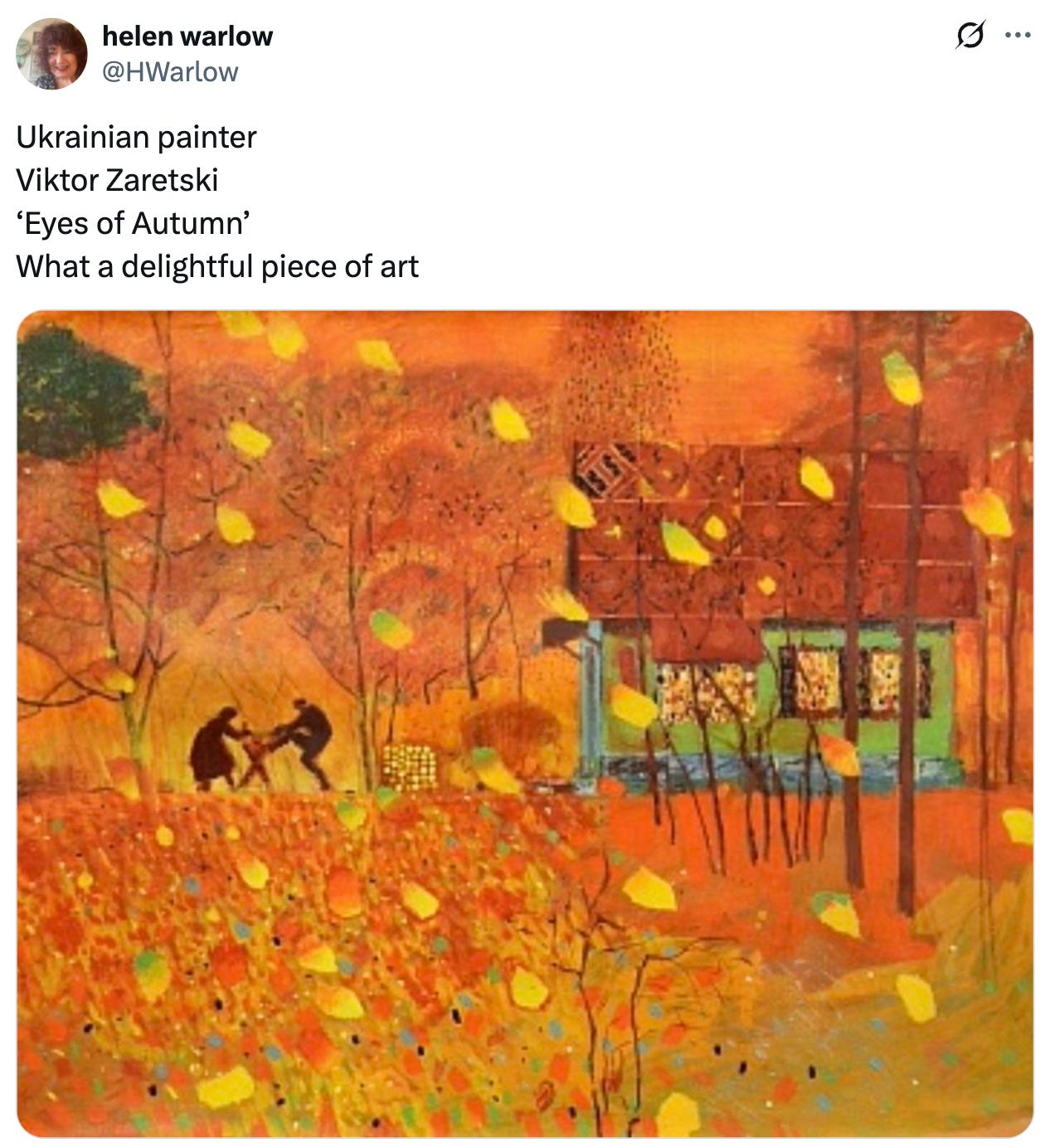

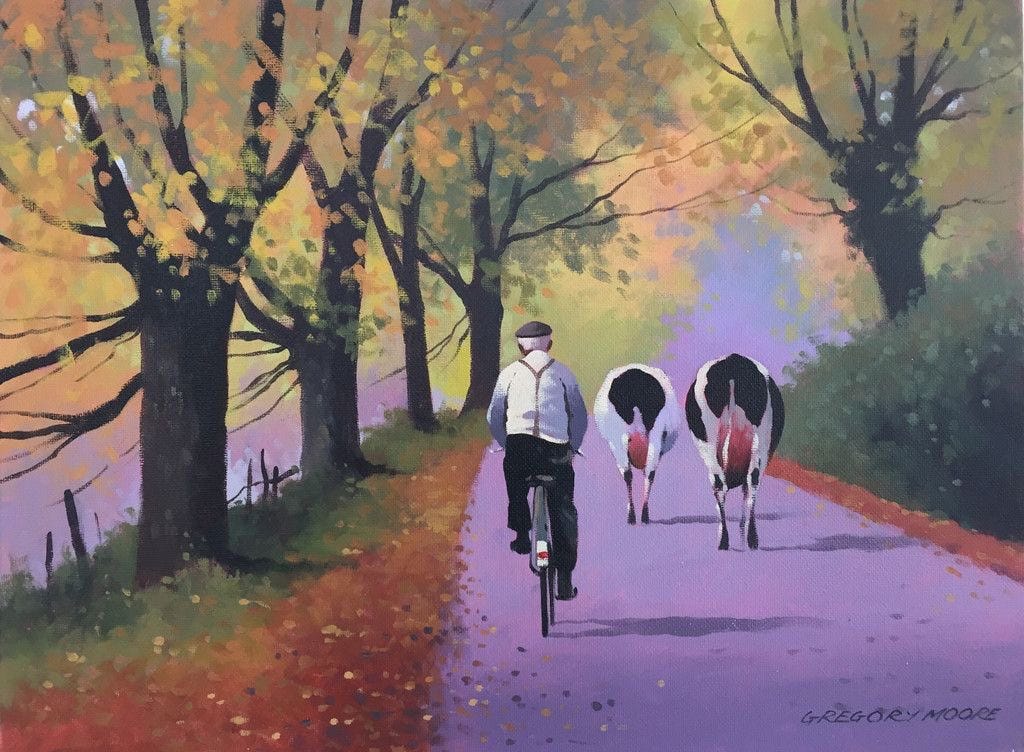

Gregory Moore Irish artist

The Right’s Co-opting of Post-liberalism

John Milbank on the 2 kinds of post-liberalism

What’s post-liberalism? It’s a term that’s been gaining attention in recent years, particularly in political discourse. For instance, after JD Vance was nominated as Trump’s vice-presidential candidate, it seemed to become a buzzword again. What does this concept really entail, especially in the context of contemporary politics?

Well, when it comes to politics, I think post-liberalism means at least two different things.

First, in an objective sense, it reflects a recognition that the liberal era may be coming to an end. By liberalism, I mean an attitude that regards the individual and individual choice as completely paramount. For a long time, across the political spectrum, liberalism has been the dominant attitude. For example, on the right, we’ve seen economic neoliberalism pushing to minimize the role of government, leaving markets to dictate not only economic outcomes but, in many cases, political processes too. On the left, liberalism has largely been expressed through an emphasis on human rights as the bedrock of political legitimacy...

One could argue that at least since the 1960s liberalism has enjoyed an almost uncontested domination, but now we’re seeing it challenged by various populist (and other) movements. There was a moment after the Cold War when some thought history had ended with the global triumph of liberal democracy—the idea that eventually, everyone would fall in line with it. But instead, what we’ve seen is communist China becoming a hybrid of communism and capitalism, regaining its confidence, while Russia has morphed into something more like a nationalist, authoritarian state—definitely not liberal democratic...

The second sense of post-liberalism is as a positive philosophy. It’s not necessarily anti-liberal; it’s not wholly against individual freedom or the idea of individuals having the freedom to make their own choices. But post-liberals argue that this focus on individual freedom alone isn’t enough to sustain political, social, or economic order. I agree with John Gray, a leading post-liberal thinker, that the Hobbesian idea that you can generate order from the chaos of competing individuals doesn’t hold up in the long term. Instead, we need a degree of social consensus and cultural coherence. There has to be a shared sense of the common good, of goods that we can only pursue together rather than purely individually. And we also need some idea of what constitutes the genuinely good life for individuals...

Post-liberalism is asking for something deeper than just improving freedom of choice, promoting equality of opportunity, or else pursuing utilitarian goals like maximizing material happiness. If we focus solely on those aspects, two major problems arise...

On one hand, you risk drifting toward anarchy. The idea that the formal pursuit of individual freedom alone can create a stable order is a fiction. In reality, this often leads to control by small, hidden groups—what you might call cabals...

On the other hand, when negative liberty – freedom from interference – isn’t enough to maintain order, we see an increasing reliance on utilitarian goals, which often means rule by so-called experts. These are people who think they are rational, educated, and therefore capable of making decisions for everyone else...

In this context, post-liberalism can be seen as a modern form of communitarianism. It prioritizes the concrete person in real, relational situations, rather than the isolated, atomized individual that liberalism often focuses on. Post-liberalism emphasizes that communities need to be organized around shared goals—collectively accepted aims that foster human flourishing...

How would you locate post-liberalism within contemporary political discourse?

I see post-liberalism as an alternative to both liberalism on the one hand and populism—especially so-called national conservatism—on the other. It’s certainly not aligned with the kind of politics Trump represents. From my perspective, it’s rather strange that the term post-liberalism has been co-opted by the political right in the United States...

To put it another way, post-liberals advocate for economic reforms that challenge neoliberalism while supporting traditional institutions like the family, without discriminating against those who don’t fit into that structure. There’s a recognition that unless we move away from economic neoliberalism, we won’t make progress on key cultural issues...

We need now to try to achieve a final synthesis, as again David Engels has suggested: to re-situate the ‘Faustian’ within the liturgical carapace of universal guidance of the social, economic and political by the reach for transcendence. The alternative will probably be a further breakdown of our civilisation at the hands of oligarchy and tyranny.

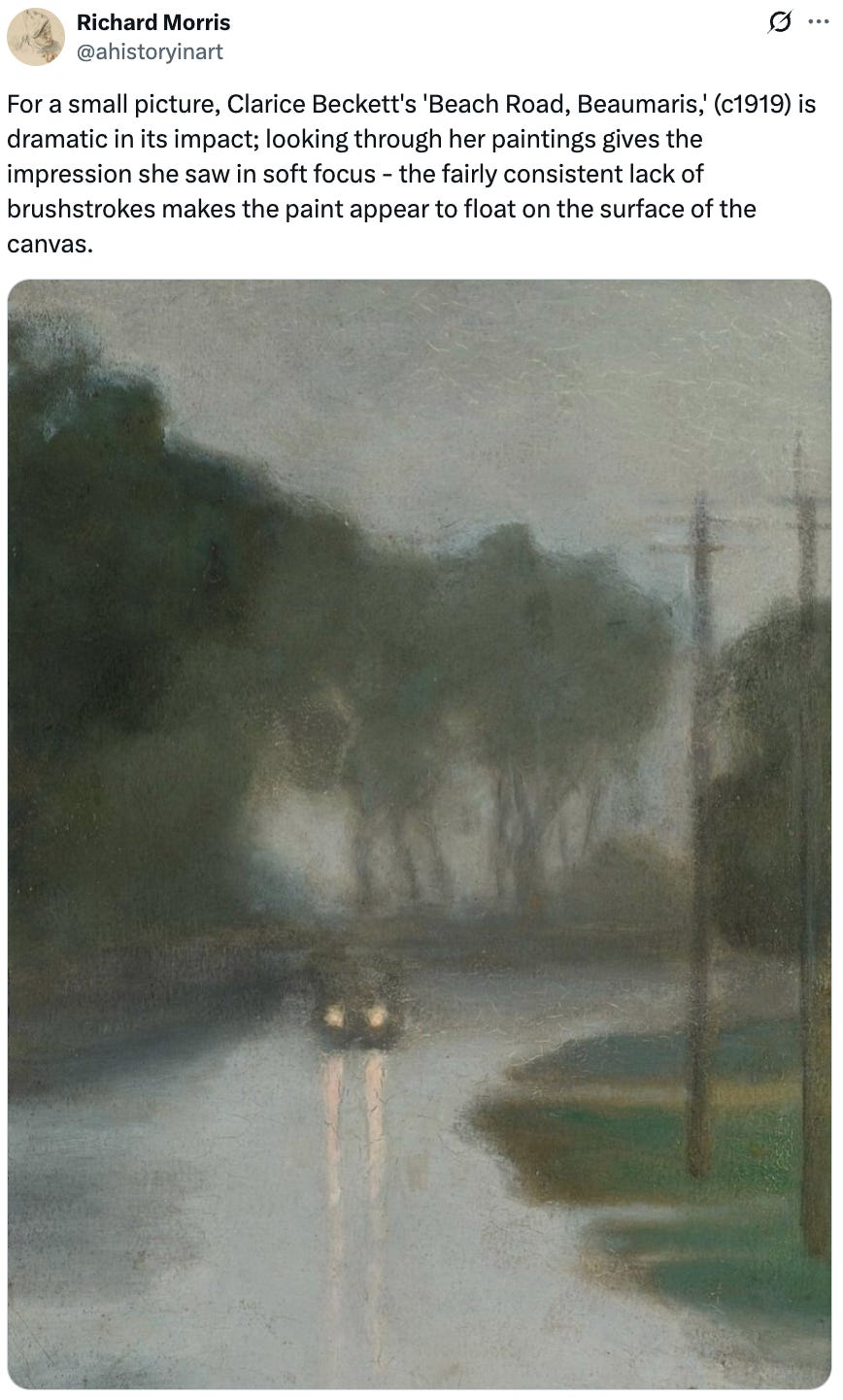

Nice to see Clarice Beckett’s work being picked up internationally!

Heaviosity half hour

The introduction to the intellectual biography of Alasdair MacIntyre. I’ve been reading it and really enjoyed this setting of the scene.

Introduction

The solution to the political problem pertains not so much to a dynamic of the good but to a balance of evils. It is achieved less by an improvement of human beings and more by a careful adjustment of powers. This is the thesis that presides over the working of liberal democracy. Contrary to what we too often suggest, the first movement of liberal democracy’s theorists is somber and without illusions. They emphasize that human beings work to become powerful rather than to become just, that power corrupts and that absolute power corrupts absolutely. Neither moral edification nor laws are enough to render citizens good and virtuous. It is useless to look to transform tyrants into generous kings, oligarchs into aristocrats, and corrupt men into wise men. It is more efficient for ambition to counteract ambition so that one cancels out the other. Liberal democracy uses egoism and ambition, which lean in principle toward tyranny, to avoid tyranny itself. Are human beings dominated by the passion to acquire more things and more power? Do they want to possess ever more, to accumulate without limits? We will not gain by groaning about the human condition, by grumbling about it indefinitely. It is better to prove our audacity, and mount the beast to train it. Vices have an advantage over virtues: they are, so to speak, regular, stable, and foreseeable. In relying on the vices, in transforming passions into interests, we can ensure that each one pursues his interest in a way that profits everyone. We ensure order by developing this regularity in disorder itself. A little unsettled by such dexterity, we should exclaim with Pascal: “The greatness of man even in his concupiscence, to have known how to draw from it an admirable rule!”

Liberalism’s adversaries have opposed this regime, sometimes in the name of nobility (the critique of the right), sometimes in the name of justice (the critique of the left).

Liberal democracy supposes that human beings are naturally unjust, and that if we allow them to, they will behave like tyrants. Socialists and communists combine this thesis with a simple sociological statement: liberal democracy comprises different social classes, bosses and employees, bourgeois and proletarians. Do we believe, socialists and communists argue, that the rich (who are powerful) love the poor (who are weak) with a pure and generous love? If every man is a potential tyrant, there is no reason for the industrialist to refrain from exploiting the workers. Why do liberals, who distrust human beings so much, not distrust the richest human beings? As human beings hardly want the good and as justice depends on a balance of forces, we should concern ourselves with the little means available to the poor. Liberal democracy provides for a balance of power, but it hardly ensures a balance within businesses or industries. As it tends to sacralize private property, it sacrifices economic equality for legal equality. In so doing, it abandons the most destitute to their own fate and to the greed of the wealthy. Liberal democracy is supposed to ensure a certain equality, but the equality that it extols remains “formal,” and we need to contrast it to a “real” equality.

Antiliberals of the right upend this critique. For them, liberal democracy seems not insufficiently democratic, but rather too democratic. They compare the modern world to the ancient world and are first and foremost struck by the progress of equality. It seems to them superficial to contrast formal equality with real equality. They remark that aristocracies have disappeared, that slavery no longer exists in law, that paternal authority has withered away, and that money everywhere exerts an equalizing power. They denounce the reign of this equality, this razing to the ground that puts everyone, including the greatness of some and the mediocrity of others, on the same level. In the name of excellence and of glory, they protest against the shrinking of the soul. They call for a new aristocracy.

If human beings fight for this or that cause, then the liberal resolves—or, more precisely, defuses—the conflict by abandoning talk of it. Everyone should decide for himself. Why risk civil war by looking to decide on a common good, when pluralism, which facilitates everything, is possible? This strategy has the merit of simplicity: human beings readily agree on trivial things (a commercial contract, for example), not on important things (such as final ends). The more serious and essential a question is, the more it is liable to enrage. The liberal technique par excellence consists in “neutralizing” the public sphere, in “privatizing” its problems. For antiliberals of the right, this privatization raises two difficulties. On the one hand, it encourages mediocrity. An entirely peaceful universe, where all preciously keep their convictions to themselves, is not the paradise that liberalism promises. It is a flattened, dehumanized world, without the martyrs or the heroes who are the salt of the earth. It is a world where human beings, abandoning self-improvement, merely enrich themselves. On the other hand, for antiliberals of the right, the hypothesis of a tranquil and depoliticized world mistakenly presupposes that human beings are essentially good, that one can disregard the aggressive urges that incite conflicts and wars. In this sense, liberals do not take the reality of evil seriously. Therefore, one should turn what seems to be liberalism’s principle, the primacy of evil, against liberalism itself.

Liberalism can be criticized in the name of justice or in the name of nobility. In the twentieth century, these two critiques culminate in totalitarianism. The struggle between communism and Nazism illustrates the deadly struggle between two crazed interpretations of justice and of nobility. The concern for social justice was brutally turned against justice itself: with the Soviet Union, the proletariat’s advocates morphed into champions of tyranny. As for the desire to reestablish a sense of heroism and of nobility, it was turned against nobility itself: far from embodying a new aristocracy, fascists and Nazis enjoyed their greatest successes among demoted citizens dominated by resentment. The two great adversaries of liberal democracy thus demonstrated their limits. Despite themselves, they established the necessity of the liberalism they abhorred. For liberals ensure the balance of powers. They separate church from state, state from civil society, man from citizen, and politics from economics, in order that the state may be as limited, restricted, and counterbalanced as possible. It is against the backdrop of the reciprocal failure of communism and Nazism that liberalism imposes itself today, as a posttotalitarianism. Liberalism comes out of its trial reinforced, since the political shape of evil was embodied with an atrocious brutality in the regimes of Hitler and Stalin. Liberalism therefore imposes itself: thanks to modern tyrannies, the political regime that starts from the affirmation of evil finds a new legitimacy. As a famous saying goes, liberal democracy “is the worst of all regimes, except for all the others.”

Is this to say that liberal democracy has no more adversaries? That it imposes itself everywhere through consensus? Far from it. The same success of liberalism brings to the fore a critique somewhat forgotten in the West today: a third critique that, without ignoring either justice or nobility, relates both to moral truth, to the objective reality of the good. Unlike the communist or Nazi challenges, this Aristotelian-inspired critique does not start from the primacy of evil to better turn it against the injustice of some and the vulgarity of others. It argues against the relativism or skepticism that theorists of liberal democracy share with their critics on the right and on the left.

Liberal democracy’s founders emphasize, above all, the disorder of the world: human beings tend neither to truth nor to the good, but to the useful and to the pleasant. It is important to base the political order on this regular disorder. It is vain to look to teach character or to encourage the virtues. On the one hand, there is no natural tendency on which we could rely. These virtues are in fact against nature and do violence to human nature. Man is by nature asocial and apolitical. On the other hand, there is no reason to think that the good of the individual coincides with the good of the city. There is not, properly speaking, a “common good”; at most there is a “general interest.” By overemphasizing the good, we come to quarrel about abstractions and incite civil wars and wars of religion. By overemphasizing the good, we are led to underestimate the perversity of which those who aspire to tyranny are capable and to forget that, in certain situations, it is perhaps necessary to violate the rules of morality to preserve political liberty. It is dangerous to rely on a natural order that does not exist. The state alone ensures the order that renders a certain peaceful coexistence possible. Since the good is reducible to the useful and the pleasant, political life should therefore not strive for the good, but for the useful and the pleasant. By contrast, for the neo-Aristotelian critiques of liberalism, the good is not reducible to the useful or the pleasant. The city should teach the natural desire to live in society, the natural desire for the good and the true. The city itself should also make good use of it. Justice and law are fully intelligible only by reference to this natural desire and the natural order that it presupposes. Man is a social and political animal; it is important to organize the city around this good nature, by ensuring the education of character and by encouraging the virtues. It is not enough to organize the state as for a nation of intelligent devils: we need to rely on the aspiration for the good.

For liberals, the state should be considered “neutral” about the idea of the good, and it is up to the individual to look for happiness and truth, for himself and through himself. It is in this sense that liberalism is a kind of individualism and positivism: morality is a private affair, and the just is separate from the good. Insofar as liberals are concerned about the good or about happiness, it is to make it an individualized question: it is up to the individual, and himself alone, to decide his morality and his religion. But can the individual discover the good and the true independent of authoritative social forms and traditions? In the eyes of neo-Aristotelians, liberalism, which looks to avoid disagreements about the nature of the good and to circumvent them by privatizing or depoliticizing the question of the good, distorts the care of the virtues and the transmission of truth by making the essentials rest on the frail shoulders of the individual. A too-exclusive concern with tyranny and anarchy impoverishes existence. The primacy of security entails forgetting the good that nourishes interior life. The state and the law cannot and should not be perfectly “neutral” in morality. Justice is unthinkable if it is completely separated from morality. Positive law is only intelligible to the extent to which it refers to natural justice. Individualism that consists in choosing for the self a reputedly private morality is an error or an illusion.

This opposition crystallizes over the question of freedom. For liberalism’s founders, evil is constitutive of political life. Correlatively, freedom is in the last analysis the absence of evil; which is to say, on a political level, freedom is the absence of tyranny and the absence of coercion. It is a “negative” liberty. Freedom is understood by reference to a balance of powers and has no specific relation to either the good or the true. However, for the neo-Aristotelian school, freedom is subordinated to the good and the true. Freedom is not only a matter of security, the absence of physical or legal obstacles, or autonomy. First and foremost, it involves grasping the good. Liberty includes a “positive” dimension. It is not enough to have freedom; we still need to become free. Subjective freedom should be related to the objective character of the good. We cannot give all of freedom’s meaning to the freedom of indifference without counterbalancing it by the concern for wisdom. It is not enough to be able to do what we want and to know what we do not want; we must still give ourselves the means to know what we want, what we would like, or what we should want. The refusal of all dependence renders moral life anemic. At the most fundamental level, freedom is achieved not so much by the absence of obstacles but by a truth that enables removing these obstacles. A certain “paternalism” is at once inevitable (every society, whether it wants to or not, transmits a certain idea of the good) and desirable.

Against the philosophical skepticism that is the basis for the primacy of evil, numerous voices propose to straighten out our conceptions of justice and correct liberalism’s own crookedness. Have we not lost the difference between liberty and license? This is what the contemporary critics of liberalism insist, beginning with the most determined among them, Alasdair MacIntyre, who is inspired by the Aristotelian tradition to recover an idea of the good and of moral truth.

At “MacIntyre, Alasdair,” a dictionary might indicate “born 1929 in Glasgow” and should add “historian of moral philosophy.” The three principal works of MacIntyre—A Short History of Ethics (1966), After Virtue (1981), and Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988)—each tell, in their own ways, the same history, which begins in Greece with Homer and comes to an end in the twentieth century with nihilism. These histories of ethics establish, on the one hand, the dependence of moral life on traditions of enquiry and, on the other hand, the progress of relativism and irrationalism under the corrupting influence of individualism. Perhaps it would be better to translate After Virtue as The Misfortunes of Virtue. If this analogy with the Marquis de Sade’s novel does not suggest that philosophical digressions and narrative character are inclusive of each other, at least it suggests that the liberal category of the private is not as morally indifferent as it is said to be. In his books, MacIntyre intends to establish that the unilateral progress of freedom disintegrates rationality, feeding the moral relativism that all his work denounces.

In his eyes, the civil liberty that citizens of liberal democracy enjoy is too often exercised to the detriment of interior freedom. Individual autonomy is not self-sufficient; it ends up exhausting traditions, which it requires without being sufficiently aware of it. Autonomy, reduced to its own means, comes to undermine the foundations of the moral life and capsizes. The indefinite deepening of individualism has gradually corroded the meaning of truth that practical reasoning presupposes. The subjective character of freedom should be compensated with the objective dimension of a tradition: consent must be rebalanced with wisdom. If we grant liberalism the upper hand in all aspects of existence, human beings find themselves distraught, desolate, mutilated, and deprived of goals or ends. Against individual rights, MacIntyre counters with a conception of justice that takes into account the importance of forms of life and of moral authority. It is not enough to flee evil; it is still necessary to look for the good. Negative liberty, conceived as the absence of coercion, is not enough: it is necessary to add a “positive” dimension. MacIntyre develops a theory of freedom as participation in something greater than oneself. He subordinates the question of freedom to that of practical rationality, to demonstrate that, in the last analysis, the capacity to choose without coercion must be subordinated to the capacity to choose intelligibly or reasonably. He analyzes the limits of the absolutization of individual consent, which is to the detriment of authority and moral excellence. He appeals to virtue and character formation, which liberalism tends to neglect for “efficiency.” True justice and true nobility, pursued with such relentlessness by liberalism’s adversaries on the right and left, depend precisely upon virtue and character formation.

MacIntyre describes a world in which one no longer knows what one wants, a world which no longer knows toward what end it advances. He writes:

What strikes me most basically and most finally about our society is its domination by the concept of “getting on.” One gets on from one stage to the next on an endless conveyor belt. One goes to a primary school in order to pass the eleven plus in order to go to a grammar school in order to go to a university in order to get a degree in order to get a job in order to rise in one’s profession in order to get a pension. And those who have fallen out are not people who have found a true end; they are mostly people who have got off, or been pushed off, the conveyor belt. Last year a student whom I knew well had a break-down as a result of taking seriously the question, “What am I studying for?” The chain of reasons has no ending.

MacIntyre describes the triumph of instrumental reasoning, a society that has become expert in means. But it has lost the very meaning of truth, by reference to which a worthwhile education is understood. It is an efficient society, where utility is maximized, but for a goal that fades away as one approaches it. As a good Aristotelian, MacIntyre deplores the absence of ends and regrets that society does not make the goods that could nourish moral life accessible to its members. Hobbes, who is perhaps the most eloquent spokesman for the political tradition against which MacIntyre writes, insists to the contrary that one analyzes life in terms of means and not ends.

The Felicity of this life, consisteth not in the repose of a mind satisfied. For there is no such Finis Ultimus, (utmost ayme,) nor Summum Bonum, (greatest good,) as is spoken of in the Books of the old Morall Philosophers. Nor can a man any more live, whose Desires are at an end, than he, whose Senses and Imaginations are at a stand. Felicity is a continuall progresse of the desire, from one object to another; the attaining of the former, being still but the way to the later. The cause whereof is, That the object of mans desire, is not to enjoy once onely, and for one instant of time; but to assure for ever, the way of his future desire.

In the absence of a summum bonum, happiness is about fleeing from evil or about the accumulation of means for the goal of self-preservation. Aristotle ranks among the “old Morall Philosophers,” from whom Hobbes looks to distinguish himself. Hobbes does not describe life as oriented toward a determined truth or good, but as a forward march in which the only goal is in reality a means: the “assuredness” of the route—that is to say, the absence of danger and the absence of evils. Hobbes readily concedes that in thus considering practical life, we come to lose all moral objectivity and reduce the good to the pleasant. He writes, “Whatsoever is the object of any mans Appetite or Desire; that is it, which he for his part calleth Good: And the object of his Hate, and Aversion, evill.” Hobbes fears first and foremost the state of nature, a war of all against all, from which he looks to have us escape in an efficient and intelligent way, with moral subjectivism as the price to pay. MacIntyre does not believe that the good needs to be reduced to the pleasant, save to impoverish human existence to an unacceptable extent. The world that Hobbes describes really is the world as it has become. But this is to be deplored, not welcomed. Whose justice and which rationality should we make our own? Not the justice and rationality of utilitarian and positivist inspiration, but the justice and rationality of Aristotelian inspiration, which draws its substance from the implementation of the good and the contemplation of the true.

Today, at least in the West, liberalism imposes itself. But an anxiety tends to spread. The soul is troubled. One comes to ask whether individual autonomy has not carried the day so well that it is collapsing in on itself. If individualism is surely in many respects a political solution, it can also constitute a psychological and spiritual problem, to the point of casting doubt on the foundations of liberalism. The present political triumph of liberalism is also the triumph of autonomy over all socially embodied authority. But does liberalism not triumph even when the meaning of this autonomy has become uncertain?

The present situation is paradoxical in that it seems that one should turn toward the traditional adversaries of liberalism to give substance to liberalism itself. The critiques of liberalism studied here come after the failure of the great antiliberal waves: socialism, fascism, Nazism, and Marxist-Leninism. They do not cast doubt on liberal democracy as a political form or political regime, even though they criticize the way in which most theorists give an account of liberal democracy, and they warn against the atomist, relativist, and finally nihilist dynamic of a certain liberalism.

To the extent that liberal democracy imposes itself and proves its worth, it becomes more artificial to insist on the primacy of evil and more tempting to offer an Aristotelian-inspired reinterpretation of the regime. We can thus show that liberalism cultivates certain veritable goods, starting with concord and justice. We can describe liberalism as a mixed regime, which, by means of representation, reconciles democratic and aristocratic elements, harmonizing their respective parts to consent and wisdom. We can elaborate an analysis of liberal democracy in terms of the natural law and the common good. From this point of view, a durable and satisfying political regime is achieved less by a balance of evils than by a dynamic of the good. The liberalism that avoids evil does not forbid the liberalism that looks for the good.

A member of the Communist Party of Great Britain in the late 1940s, an activist of the first New Left ten years later, and a Trotskyist in the first half of the 1960s, MacIntyre immigrated in 1969 to the United States, where he renounced all political engagement. As an academic, he taught theology, sociology, and philosophy at Manchester, Leeds, Oxford, Princeton, and then at the University of Essex. In Boston in the 1970s, he was successively a professor at Brandeis University, Boston University, and Wellesley College. He finally taught at Vanderbilt University (1982–88), the University of Notre Dame (1988–94), and Duke in North Carolina (1994–2000), before coming back to Notre Dame until his retirement. First influenced by the young Marx and the late Wittgenstein, he turned toward Aristotle in the early 1970s, embarrassing his old allies and bewildering his new friends. He was first a Presbyterian, and even envisioned becoming a pastor. In the mid-1950s, he embraced Anglicanism, before losing his faith several years later. He converted to Catholicism in 1983. First attracted by the theology of Karl Barth, he ended up a disciple of Thomas Aquinas. As a Marxist, Barthian, Wittgensteinian, Aristotelian, and Thomist, MacIntyre places at the heart of his reflection what liberalism keeps on the margins of politics: the soul, community, and truth. Thus from apparent chaos, something constant emerges. The critique of liberalism is at once the continuous base and the final cause of his work.

Why study this tormented thinker? I see three reasons. First, even though his intellectual journey provides a very clear understanding of the intellectual history of the second half of the twentieth century, it remains misunderstood. In France, it is not known that MacIntyre constitutes one of the great authorities for the debate in Anglo-American moral philosophy and politics. In his home in the Anglo-American world, MacIntyre’s latest works are read without much concern for their genesis. Second, it is generally admitted that the range of his reflection remains difficult to grasp, even though there is agreement to see him as a storyteller of lively charm, a brilliant historian, a daring polemicist, and the author of profound views on the twentieth century’s evil. Finally, if his intellectual journey is atypical to the point of being unsettling, and yet if the critique of liberalism constitutes the guiding principle of his works, then his apparent atypicalism is turned on its head. MacIntyre becomes a privileged figure in the antiliberal repertoire, one of its eminent cases. It is not so much MacIntyre that turned me toward the theme of “community.” Rather, I started from the critique of liberalism and turned toward MacIntyre. His trajectory enables us to take another look at a great part of the history of the intellectual opposition to bourgeois individualism, and the internal tensions in his thought convey the tensions proper to this opposition. I did not choose his work because it offers a demarcated object of study according to the methods of the university’s disciplines, but because it enables us to explore the multifaceted legacy of Aristotle, Rousseau, and Marx. In reducing common life to the lowest common denominator, in reducing justice to individual rights alone, and the good to the useful or the pleasant, we kindle the need for a reaction. As a former communist concerned with justice and an Aristotelian concerned with nobility and truth, MacIntyre marvelously illustrates this aspiration.

From the 1970s, even before MacIntyre turns toward Thomas Aquinas, he is the object of a petty but significant polemic: “In the past he has been a ‘Christian’ without God, a ‘Trotskyist’ without commitment to revolution, a ‘Marxist’ patronized by the Central Intelligence Agency, an ‘anti-elitist’ adornment of the world’s most mediocre and servile bourgeois intelligentsia, a ‘socialist’ avid for the approval of his social ‘superiors.’ Now he is a liberal . . . a libertarian instrument of academic authoritarianism.”

The text is ambiguous, for we do not know whether it suggests through its quotation marks that MacIntyre, in the last analysis, was never what he purported to be, invariably remaining a hypocritical “valet of capitalism,” or whether it points to changes so crazy that it discredits him. These flip-flops, it is true, are manifest. But perhaps MacIntyre is nevertheless sufficiently single-minded, so that we should concern ourselves with the meaning of these ruptures. I would like to establish that his intellectual journey clarifies the history and the nature of anti-individualism. Moreover, I would like to treat his successive turnarounds as historiographical difficulties, while striving to show his unity of purpose. In the contemporary repertoire, MacIntyre is not a neutral figure. He is one of the rare thinkers today to have remained faithful to the antiliberalism of his youth, one of the rare critics of liberalism not to have stopped thinking after the fall of communism, and one of the rare thinkers to have been able to reorient his outlook in a new direction. Yet even though he is a complicated person, MacIntyre hardly discusses his past with us. “To write a worthwhile autobiography,” he remarks, “you need either the wisdom of an Augustine or the shamelessness of a Rousseau.” I however intend to reconstitute his intellectual journey, as a way to outline the biography of a problem.

Upstream from MacIntyre’s diverse political engagements, I would like to show that a philosophy is at work, and, alongside his philosophy, a theology. Through him I shall study the contemporary critique of liberalism, as it has developed after the failure of communism (in politics), after Ludwig Wittgenstein (in philosophy), and after Karl Barth (in theology). In each instance, I shall try to show MacIntyre’s philosophy: that, limited to his own strength, the individual is not always able to find the good and the true to which he aspires.

In each of the three chapters, I shall take a different starting point: for politics, the history of the New Left; for philosophy, the moral critique of Stalinism (or the articulation of politics and morals); and for theology, the question of secularization. In each instance, I shall attempt to show that the starting point leads to the rediscovery of the social nature of the human being and therefore of a certain conservatism: “a new conservatism,” a “philosophy of tradition,” and a “theology of the tradition.”

The theorists of liberalism privilege the circumvention of evil over the search for the good. On the whole, they hold to a minimalist conception of the good. They tend to subordinate the question of the good life to that of life simply, to security. They delegate the quest for the good to the individual alone: it is for him to find wisdom and happiness, for himself and through himself. In the first chapter of the book, I shall show that in the eyes of the author of After Virtue, lives are impoverished to the extent that one adulterates or privatizes the concern for the good. In the second chapter, following MacIntyre, I shall explain that the quest for the good life necessarily takes a collective form, for all individual reasoning participates in collective reasoning, and it is by reference to moral consensus and a tradition that the individual can judge, weigh the pros and cons, and prove his prudence and virtue. Finally, in the third chapter, I shall take up again the themes of the first two chapters from a theological angle, showing that for MacIntyre, secularization is one of the most important dimensions of the impoverishment of human existence, and that it is also by reference to “The Tradition,” in the theological sense of the term, that the individual can reason morally, become virtuous, and lead a worthwhile life.

Tocqueville thus depicts the personality of Louis-Philippe, the most “liberal” of princes in France’s history:

Enlightened, subtle, supple, and tenacious, fixed exclusively on the utilitarian and filled with such profound contempt for truth and such complete disbelief in virtue that his intelligence was consequently dimmed, he not only failed to see the beauty that truth and honesty always exhibit but also failed to understand that they can frequently be useful. He had a profound understanding of men, but only of their vices. In religion he had the incredulity of the eighteenth century and in politics the skepticism of the nineteenth. An unbeliever himself . . . his ambition, limited only by prudence, was never fully satisfied nor out of control and always remained close to the earth.

A liberal himself, Tocqueville a priori had some sympathy for the July Monarchy. He preferred it to the regimes that came before it and the regime that followed it. At the same time, he could not prevent himself from disdaining it. By keeping only to the perspective of what is evil, we run the risk of dangerously narrowing our range of vision.

Thanks for the Stewart Lee clip - one of his funniest I think. I am also a fan but, of course, not at all like the ones he describes in:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NtFJ1HT3gto

Wisdom: " optimism is not naïve; it’s a civic responsibility"

Thanks for sharing "Then “Reasons to Be Cheerful” closed things on a high, a necessary reminder that optimism is not naïve; it’s a civic responsibility and very necessary when smart people have a habit of being cynical and negative..."