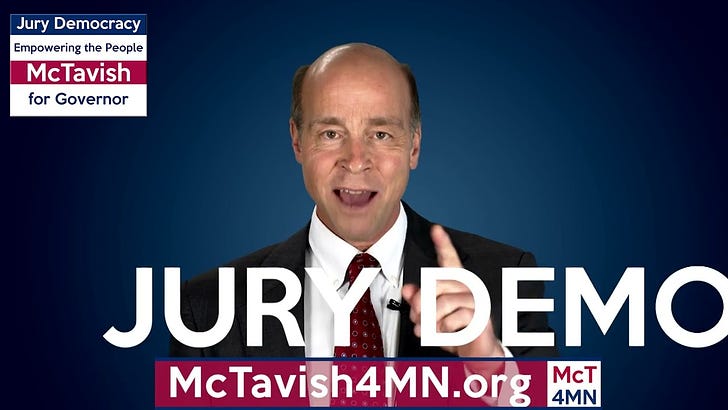

One of two US candidates for jury democracy I’ve been talking to

A St Bernard in Europe, A Dachshund in LA

My cousin Lawrence reprising the life of his grandad and my Dad’s uncle: the composer, Ernst Toch. The Lilly in the story is his mother Marianne’s sister.

Two dachshunds meet on the Palisade in Santa Monica and one says to the other, “Here, it’s true, I’m a dachshund, but back in the old country, I was a St. Bernard!”

Poor guy, my grandfather Toch: not just because his forced flight from Berlin in 1933 (and eventual resettlement in Southern California) saw the end of that stellar reputation (notwithstanding his continued productivity through the end of his life … but doubly so in that further down the line he got stuck with me as his musical executor, a role for which I was spectacularly ill-suited, not being the slightest bit musical, and worse. Indeed my astonishing amusicality, particularly given the positive surfeit of musical inheritance flowing into my personal genome (not only had my mother’s father been this astonishing prodigy but my father’s mother had been the head of the Vienna Conservatory of Music’s piano department and a concert soloist herself), the fact that I literally cannot hear whether any given sequence of notes is going up or down, used to so confuddle my longtime neurologist pal Oliver Sacks that he devoted a full page to the scandal in his book Musicophilia.

Gorbachev: a couple of views

Gorbachev was no saint. But he was a kind of hero

Gorbachev’s greatest virtue was his capacity to fail productively, to fail and yet to learn. Unlike so many leaders, he evolved. He came to power convinced all the system needed was a little modernisation and a light rebranding, that the party was his greatest ally and instrument and eventually came rightly to see it as the greatest obstacle to reform.

Of course, his refusal to use force to try and hold together the empire, whether the Warsaw Pact or the Soviet Union itself is also his greatest failure in the eyes of men such as Putin. …

Gorbachev was a complex figure. A reformist who had made his way up the corrupt, clientelistic structures of the party; a peace-maker who still had blood on his hands; a ruthless politician who was willing to bow to new realities and surrender power with good grace. He was a failure as a Soviet leader, but in ways that suggest he was that much better a human being for it.

After all, the last and best encomium to Gorbachev is perhaps precisely that Putin seems to have loathed him.

Branco Milanovic: A politician who did not want to rule

God has not been kind to Mikhail Gorbachev to not allow him to die before February 24, 2022 and not witness the senseless destruction of everything he stood for. And perhaps even to reflect how sometime the decision not to use force may later lead to a much greater carnage. If Mikhail Gorbachev had maintained the Soviet Union (perhaps without the Baltics), and used force the way that Deng Xiaoping did, we might not be now looking at a senseless internecine war that has already claimed dozens, if not hundreds, of thousands of lives, and which in the worst case might degenerate into a nuclear holocaust. Politicians, even those who are the most humane, must unfortunately make this calculation where human lives are just numbers.

Gorbachev openly refused to do so. Perhaps to openly state that was a mistake: nobody was any longer taking him seriously, from Baku to Washington, although he sat atop of the largest nuclear arsenal in the world, the second largest military in the world, hundreds of thousands of police and domestic security forces, and as the Secretary General of the monopolistic party disposed of unquestionable loyalty of 20 million of its members.

By the standards of statecraft, he must be judged harshly, like one of the most extraordinary failures in history. By the standards of humanity, he must be judged much more kindly: he allowed millions to regain freedom, not only proclaimed, but stuck to the principles of non-violence in domestic and foreign affairs, and left his office willingly, when he did not need to do, simply because he did not want to fight and risk lives in order to keep it. But being nice and, in fact, anti-political, he left the field open to much worse men.

How the West betrayed Mikhail Gorbachev and seeded the Ukraine conflict: Thomas Palley

Even after the Soviet Union’s dissolution, the disaster of economic shock therapy, and the looting of Russia, Gorbachev’s vision might still have been realized. However, it was decisively foreclosed by eastward expansion of NATO.

As documented by Ambassador Jack Matlock Jr., the last US ambassador to the Soviet Union, a critical element in Gorbachev’s ending of the Cold War was agreement that there be no eastward expansion of NATO beyond inclusion of East Germany. That handshake agreement was essential for Russian national security peace of mind.

Yet, after the Soviet Union’s disintegration, the West exploited Russia’s weakness to expand NATO to its borders. The result was destruction of the basis for trust and creation of an enduring rationale for Russian military fears.

NATO was established as a Cold War defensive alliance. It is understandable that it continued, but eastward expansion was an unambiguously aggressive act that has only worsened the security of original NATO member states. The new members had negligible military assets, but all brought massive conflict risk. Almost all had non-existent democratic traditions, long histories of political intolerance, histories of conflict with Russia, and were intolerant of ethnic Russians within their borders. Their joining NATO meant original member states committed to defend countries which were likely to provoke conflict with Russia.

And see this post for his dim view of American adventurism, or perhaps that should be American hegemonism — and of our flirting with nuclear war.

Yes, sanctions on Russia are working: Noah Smith

I encounter a lot of people — and some op-ed writers — who claim that the sanctions on Russia aren’t working. The three main reasons they give are that:

The ruble is strong,

Russia is managing to sell lots of oil, and

The Russian economy has contracted by less than expected.

In fact, all three of these things are true.

The only purpose of sanctions that makes any logical sense is this: Sanctions should make it harder for Russia to prosecute its invasion of Ukraine, as well as any other future invasions that Putin may decide to carry out. And the way to weaken Russia’s military machine is to weaken Russia’s defense production. … In that sense, as we’ll see, sanctions are already working quite well.

So why is the ruble doing so well? The answer is that Russian exports have risen, while Russian imports have collapsed. But remember, reducing Russian imports was the whole point of sanctions! Russia needs to import a ton of parts and machinery in order to make tanks, missiles, air defense radars, jets, and all its other implements of destruction. Now, thanks to sanctions, it can’t don that nearly as much. In fact, exports to Russia have rebounded a bit since the initial plunge, but almost all of the rebound has been in consumer goods, rather than in machinery, materials, and other “dual-use” goods. And that’s exactly what we should want — we’re not starving the babushkas, but we are starving Russia’s military machine.

In other words, the strong ruble is pointless, because the cause of the strong ruble is that sanctions are preventing Russia from getting the imports its military needs.

The Cantillon Effect and Credit Cards: The $257 Billion Payments Mess

There’s very little competition in the payments system. VISA and Mastercard control 70% of this highly concentrated market. To give you a sense of the market power at work here, last year credit card networks raised their swipe fee prices to merchants by 24% and swipe fees are now the second highest cost for most businesses, after labor. In Europe, fees are much lower, because there’s a straight cap of 0.2% per transaction.

Where does this market power come from? Well merchants, even big ones, can’t afford to not accept Visa and Mastercard, so they have to accept whatever terms they are given. One key to this market power are credit card rewards, which are the points you get when you spend money through a certain card. These rewards are roughly $20 billion a year, mostly going to high-income customers and coming from the poor. According to the Boston Fed, “the lowest-income household ($20,000 or less annually) pays $21 and the highest-income household ($150,000 or more annually) receives $750 every year” as a result of these reward systems.

Decade of the battery

Predicting the technology that will define the next era of innovation

Worth a squiz just for the graphs and links.

Why I Changed My Mind on Student Debt Forgiveness

Debt forgiveness seems regressive — handing back money to people who typically come from higher income families and who can expect to be higher income families. Anyway, that’s Economics 101. Here’s why the author of this article changed her mind.

It was the Obama administration that released more detailed data than previous administrations, revealing that whereas debt had once been concentrated among university graduates, we now saw a huge swath of students borrowing for community college and vocational training. Dropout rates were high: During the Great Recession, community colleges were bursting at the seams while their government funding was sinking. Students who couldn’t get into oversubscribed classes at community colleges turned to expensive for-profit colleges, where they earned credentials that had little value in the labor market. Many exited into a historically bad labor market during the Great Recession.

Millions of borrowers quickly fell behind on their payments. About a third of those who had borrowed to attend community colleges and for-profit colleges defaulted on their loans within a few years of leaving school. Delinquency and default were concentrated among low-income college dropouts who had debts of only a few thousand dollars.

Contrary to the popular narrative, the huge run-up in defaults has not been driven by $100,000 debts incurred by students at expensive private colleges. Rather, they are driven by $8,000 loans at for-profit colleges and, to a lesser extent, community colleges. These are the borrowers who will benefit from President Biden’s loan forgiveness policy.

The smallest loans, which have the highest default rates, are ripe for forgiveness. Collecting them is expensive for the government and harmful for the borrowers. Forgiving them will change a lot of lives without forgoing much revenue.