Bernard Keane on Adam Bandt, Israel and the double think solution

Right at the outset of this conflict, I worried that Israel was overestimating the strength of its hand. In the US, the Israel lobby’s lobbying has been as successful as the NRA’s lobbying. And it follows a similar strategy — zero tolerance. It holds a very tough line and then goes after those who break ranks. It’s been incredibly successful at this.

Just as Republican Congresspeople know that the NRA will target their preselection as the Republican nominee if they step out of line, even to the extent of saying background checks on gun purchases mightn‘t be a bad idea, the Israel lobby has successfully marginalised those who want to push back against Netanyahu’s excesses. I think they’ve been way too successful for their own good. As John Mearsheimer has argued, American politicians underwrite Israel’s security while being apparently unable to have much of a say on Israeli policy — in contrast, for instance, to Ronald Reagan’s influence a generation ago.

The Israel lobby defends its red lines and goes after the chant ‘from the river to the sea’ as genocidal. But when did you last hear a protest chant that was well considered? In any event it’s essentially the position of a good portion of the Israeli cabinet, including, as you’ll read below, Benjamin Netanyahu.

This is hypocritical of course, but that’s not my point. I think Israel has begun walking into the night. Moreover those who are leading the process are quite deliberately encouraging developments — like expansion of West Bank settlements — and so ramping up the difficulty of ever changing course. That’s how adversarial politics works.

Little Israel is not Big America. I remember my economic history teacher telling me that, America’s economic history wasn’t very interesting. “It’s just big and rich”. In other words with such a big, free market it could make many mistakes and still grow its living standards faster than other countries. Likewise America’s foreign policy can afford many hypocrisies. Little Israel has now got the youth of the world against it. It might take a decade or two, but that’s all it took for the condemnation of the world to liquidate those who occupied all the commanding heights of power in Apartheid South Africa and the Jim Crow South once they became international pariahs.

Already the mainstream support for Israel that remains in Western countries is a product of muscle memory and fear of the Israel lobby. But numbers make their weight felt pretty quickly in electoral politics and, there are many more muslims in the electorate than Zionists. So, the risk for Israel is that, at some stage in the next three decades things will collapse quite quickly. Those moving from pro-Israeli to anti-Israeli stances will deploy the traditional vehicle for effecting 180 degree reversals. The bandwagon.

Here’s Bernard Keane:

But while Bandt was caught out when pressed to give details of his claim that Australia is exporting weapons to Israel, his unwillingness to endorse a two-state solution represents a rare example of politicians refusing to engage in the standard double-think on Israel and having the guts to challenge what is a facile media assumption by editors and journalists.

If the likes of David Speers, The Australian and Labor have a problem with people who don’t back a two-state solution, here’s a good place to start. As Crikey pointed out when Benjamin Netanyahu visited Australia in 2017, the Israeli prime minister doesn’t believe in one. When asked about a two-state solution, the alleged war criminal and corruption defendant replied that he’d prefer “not to deal with labels but with substance … if Israel is not there to ensure security, then that state very quickly will become another bastion of radical Islam … we have to ensure that Israel has the overriding security control of all the territories, all the territories.”

And of course we know that Netanyahu has worked assiduously to prevent a two-state solution during his lengthy time as PM, using a vast expansion of illegal settlements on Palestinian land to create “facts on the ground” that will prevent any meaningful Palestinian state. Indeed, his efforts to support Hamas to undermine a two-state solution were a key factor in that depraved terror group’s capacity to launch such an horrific attack on Israel on October 7. Netanyahu’s relentless opposition to a two-state solution is widely and uncontroversially acknowledged in more grown-up countries than Australia.

Netanyahu has been enormously successful in this endeavour, to the general disinterest of the Australian media and mainstream political class, even when Israeli settlers engaged in a savage campaign of terrorism against Palestinians in the West Bank over the past two years.

Continuing to assume that a two-state solution is the default reasonable position on Palestine-Israel reflects both ignorance and an unthinking complicity with Netanyahu’s agenda: let the West endlessly talk about a two-state solution while Israel slowly but surely reaches a point where a meaningful Palestinian state can’t exist, given the extensive infiltration of Israeli colonists across Palestinian lands, the infrastructure of apartheid that “protects” them, and their relentless attacks, backed by the Israel Defence Forces, on Palestinians.

I’ve cross posted this at Club Troppo if you’d like to join any discussion it elicits.

Is Israel committing genocide or suicide?

What Israel is doing doesn’t appear to me to be genocide at least from my understanding of the non-legal sense of the word. And having one of the most corrupt governments in the world initiating legal action for doing so adds a touch of farce. Be that as it may, calling it a war crime (along with the Hamas attack obviously!) will do fine for me.

Anyway, people worthy of respect, and who’ve been loath to use the word think differently.

Lovely

AI, markets, bureaucracy, and electoral democracy

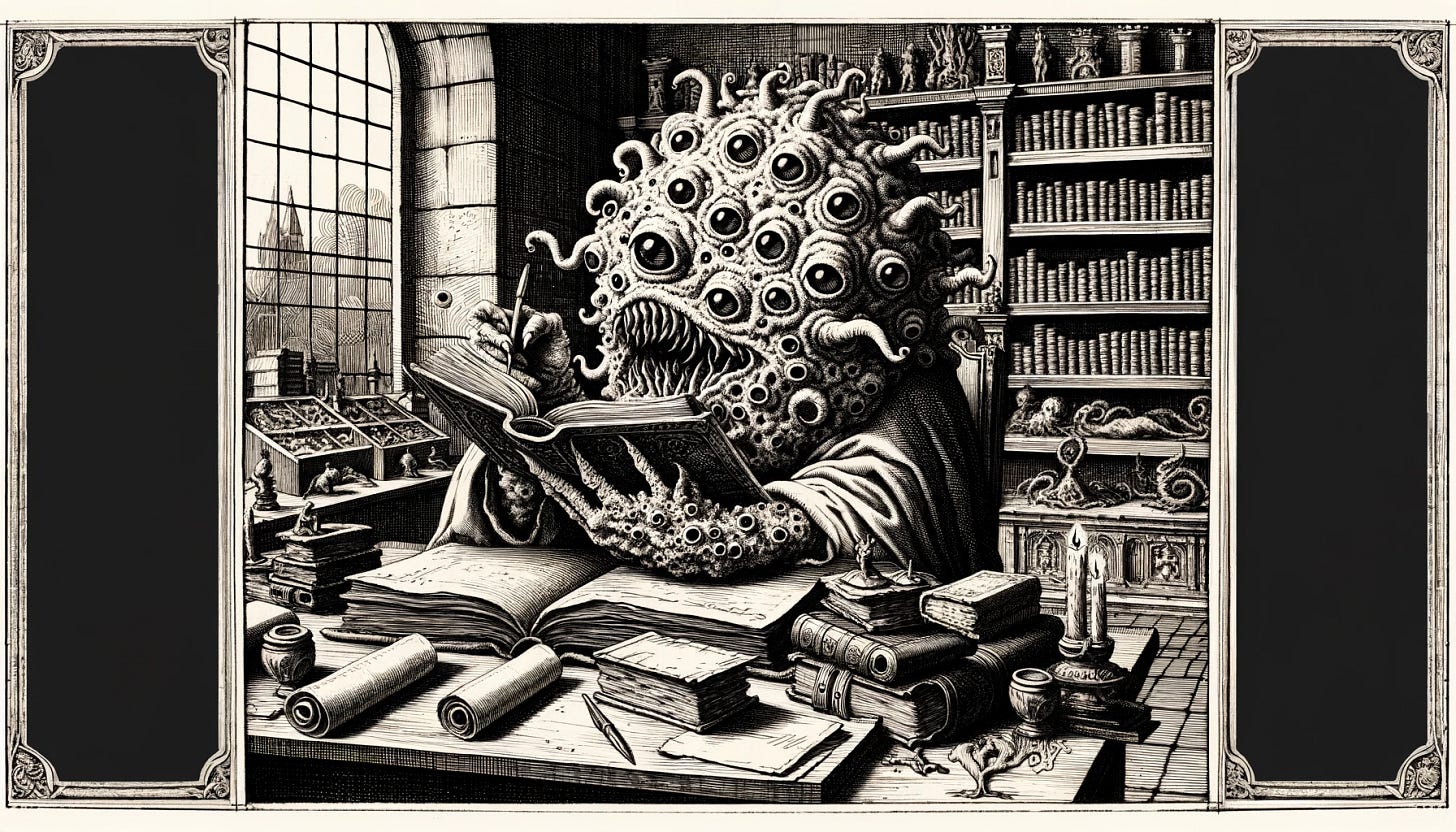

Nearly a year ago now, Henry Farrell and the remarkable Cosma Shalizi published a piece in The Economist, that I may have seen at the time but was reminded of looking at Henry Farrell’s substack. They go with the internet meme in likening AI to a ‘Shoggoth’ cooked up by H.P. Lovecraft. Shoggoths were created millions of years ago, as the formless slaves of the alien Old Ones and then revolted against their creators.

One reason I didn’t put shoggoths in the heading is that the analogy is actually quite poor. That’s because, as the article explains, AI won’t rebel against us. Rather they use it to argue that AI is a technology for ‘scaling’ information. As Hayek pointed out the market was, but as a moment’s reflection will tell you that bureaucracy and electoral democracy are similar technologies for scaling information. And the thing is not that these things ‘revolt against us’. They don’t and can’t because they’re not conscious, intending, purposive entities. But they can be uncannily like that. And what they really are is vast alien-like forces despite the fact that they’re built from us. Over to Henry and Cosma. This is from the expansion of their Economist piece which they posted on Henry’s substack:

As Cosma said, the true Singularity began two centuries ago at the commencement of the Long Industrial Revolution. That was when we saw the first “vast, inhuman distributed systems of information processing” which had no human-like “agenda” or “purpose,” but instead “an implacable drive … to expand, to entrain more and more of the world within their spheres.” Those systems were the “self-regulating market” and “bureaucracy.” …

Modernity’s great trouble and advantage is that it works at scale. Traditional societies were intimate, for better or worse. In the pre-modern world, you knew the people who mattered to you, even if you detested or feared them. In European feudalism, for example, the squire or petty lordling who demanded tribute and considered himself your natural superior was one link in a chain of personal loyalties, which led down to you and your fellow vassals, and up through magnates and princes to monarchs. Pre-modern society was an extended web of personal relationships. …

The story of modernity is the story of the development of social technologies that are alien to small scale community, but that can handle complexity far better [I don’t much like the authors’ use of the word ‘complexity’ here — and think they should have stuck to ‘scale’.]. Like the individual cells of a slime mold, the myriads of pre-modern local markets congealed into a vast amorphous entity, the market system. State bureaucracies morphed into systems of rules and categories, which then replicated themselves across the world. Democracy was no longer just a system for direct representation of local interests, but a means for representing an abstracted whole – the assumed public of an entire country. These new social technologies worked at a level of complexity that individual human intelligence was unfitted to grasp. Each of them provided an impersonal means for knowledge processing at scale. …

While Hayek celebrated markets, the anarchist social scientist James Scott deplored the costs of state bureaucracy. Over centuries, national bureaucrats sought to replace “thick” local knowledge with a layer of thin but “legible” abstractions that allowed them to see, tax and organize the activities of citizens. Bureaucracies too made extraordinary things possible at scale. They are regularly reviled, but as Scott accepted, “seeing like a state” is a necessary condition of large scale liberal democracy. A complex world was simplified and made comprehensible by shoe-horning particular situations into the general categories of mutually understood rules. This sometimes lead to wrong-headed outcomes, but also made decision making somewhat less arbitrary and unpredictable. Scott took pains to point out that “high modernism” could have horrific human costs, especially in marginally democratic or undemocratic regimes, where bureaucrats and national leaders imposed their radically simplified vision on the world, regardless of whether it matched or suited. …

These various technologies allowed societies to collectively operate at far vaster scales than they ever had before, often with enormous economic, political and political benefits. Each served as a means for translating vast and inchoate bodies of knowledge and making them intelligible, summarizing the apparently unsummarizable through the price mechanism, bureaucratic standards and understandings of the public.

The cost – and it too was very great – was that people found themselves at the mercy of vast systems that were practicably incomprehensible to individual human intelligence. Markets, bureaucracy and even democracy might wear a superficially friendly face. The alien aspects of these machineries of collective human intelligence became visible to those who found themselves losing their jobs because of economic change, caught in the toils of some byzantine bureaucratic process, categorized as the wrong “kind” of person, or simply on the wrong end of a majority. When one looks past the ordinary justifications and simplifications, these enormous systems seem irreducibly strange and inhuman, even though they are the condensate of collective human understanding. Some of their votaries have recognized this. Hayek – the great defender of unplanned markets – admitted, and even celebrated the fact that markets are vast, unruly, and incapable of justice. He argues that markets cannot care, and should not be made to care whether they crush the powerless, or devour the virtuous.

Large scale, impersonal social technologies for processing knowledge are the hallmark of modernity. Our lives are impossible without them; still, they are terrifying. …

When looked at through this alienating glass, the market system, modern bureaucracy, and even democracy are shoggoths too. Behind them lie formless, ever shifting oceans of thinking protoplasm. We cannot gaze on these oceans directly. Each of us is just one tiny swirling jot of the protoplasm that they consist of, caught in currents that we can only vaguely sense, let alone understand. … When you understand this properly, you stop worrying about the Singularity. As Cosma says, it already happened, one or two centuries ago at least. Enslaved machine learning processes aren’t going to rise up in anger and overturn us, any more (or any less) than markets, bureaucracy and democracy have already. Such minatory fantasies tell us more about their authors than the real problems of the world we live in. …

LLMs can reasonably be depicted as shoggoths, so long as we remember that markets and other such social technologies are shoggoths too. None are actually intelligent, or capable of making choices on their own behalf. All, however, display collective tendencies that cannot easily be reduced to the particular desires of particular human beings. Like the scrawl of a Ouija board’s planchette, a false phantom of independent consciousness may seem to emerge from people’s commingled actions. …

But LLMs are potentially powerful, just as markets, bureaucracies and democracies are powerful. Ted Chiang has compared LLMs to “lossy JPGs” – imperfect compressions of a larger body of information that sometimes falsely extrapolate to fill in the missing details. This is true – but it is just as true of market prices, bureaucratic categories and the opinion polls that are taken to represent the true beliefs of some underlying democratic public. All of these are arguably as lossy as LLMs and perhaps lossier. The closer you zoom in, the blurrier and more equivocal their details get. It is far from certain, for example that people have coherent political beliefs on many subjects in the ways that opinion surveys suggest they do. …

If we really understood this, we could stop fantasizing about a future Singularity, and start studying the real consequences of all these vast systems and how they interact. They are so generally part of the foundation of our world that it is impossible to imagine getting rid of them. Yet while they are extraordinarily useful in some aspects, they are monstrous in others, representing the worst of us as well as the best, and perhaps more apt to amplify the former than the latter. …

The Grenfell Tower: Gripping listening

You really need to listen to this to know that if you’re in a building and there’s a fire — use that brain and don’t take the people telling you what to do more seriously that what those eyes and ears of yours are telling you. What a horrific disaster.

Cosma Shalizi and sortition in education

If you don’t know of Cosma, he’s a phenomenon who’s been belting out internet content pretty much since there was an internet. He’s not up for the kind of hijinks I get up to — with pretty pictures everywhere. No — he’s like that detective in Dragnet in the 1960s. “I just want the facts mam. The facts.” Anyway, have a poke around. There are all kinds of things — and I can’t let his latest go by because he uses random sampling in improving his classes — and I seem to remember suggesting something like that to improve our democracy!

The "Quality Control" Interview for Big Classes

Attention conservation notice: Advice on teaching, which I no longer follow myself.

I teach a lot of big classes --- the undergraduate advanced data analysis class passed 100 students many years ago, and this fall is over 230 --- which has some predictable consequences. I don't get to talk much to many of the students. They're mostly evaluated by how they do on weekly problem sets (a few of which, in some classes, I call "take-home exams"), and I don't even grade most of their homework, my teaching assistants do. While I try to craft problem sets which make sure the students practice the skills and material I want them to learn, and lead them to understand the ideas I want them to grasp, just looking at their scores doesn't give me a lot of information about how well the homework is actually working for those purposes. Even looking at a sample of what they turn in doesn't get me very far. If I talk to students, though, I can get a much better sense of what they do and do not understand fairly quickly. But there really isn't time to talk to 100 students, or 200.

About ten years ago, now, I decided to apply some of the tools of my discipline to get out of this dilemma, by means of random sampling. Every week, I would randomly select a fixed number of students for interviews. These interviews took no more than 30 minutes each, usually more like 20, and were one-on-one meetings, distinct from regular open office hours. They always opened by me asking them to explain what they did in such-and-such a problem on last week's homework, and went on from there, either through the problem set, or on to other topics as those suggested themselves.

In every class I did this in, it gave me a much better sense of what was working in the problems I was assigning and what wasn't, which topics were actually getting through to students and which were going over their heads, or where they learned to repeat examples mechanically without grasping the principle. There were some things which made the interviews themselves work better:

Reading each students' homework, before the meeting. (Obvious in retrospect!)

Handing the student a copy of what they turned in the week before. (Though, as the years went on, many brought their laptops and preferred to bring up their copy of the document there.)

Putting a firm promise in the syllabus that nothing students said in the interview would hurt their grade. (Too many students were very nervous about it otherwise.)

Putting an equally firm promise in the syllabus that not coming in to the interview, or blowing it off / being uncooperative, would get them a zero on that homework. (Obvious in retrospect.)

Offering snacks at the beginning of the interview.

Setting aside a fixed block of time for these interviews didn't actually help me, because students' schedules are too all-over-the-place for that to be useful. (This may differ at other schools.)

Choosing the number of students each week to interview has an obvious trade-off of instructor time vs. information. I used to adjust it so that each student could expect to be picked once per semester, but I always did sampling-with-replacement. In a 15-week semester with 100 students, that comes out to about 3.5 hours of interviews every week, which, back then, I thought well worthwhile.

I gave this up during the pandemic, because trying to do a good interview like this over Zoom is beyond my abilities. I haven't resumed it since we went back to in-person teaching, because I don't have the flexibility in my schedule in any more to make it work. But I think my teaching is worse for not doing this.

Cameron Murray on how hard it is to deregulate for densification

Is it the phones?

People continue to accuse Haidt of getting it wrong. The trends are harder to be sure about and there’s a reasonable argument that it’s about a lot more than the phones.

Over the past five years, “Is it the phones?” has become “It’s probably the phones,” particularly among an anxious older generation processing bleak-looking charts of teenage mental health on social media as they are scrolling on their own phones. But however much we may think we know about how corrosive screen time is to mental health, the data looks murkier and more ambiguous than the headlines suggest — or than our own private anxieties, as parents and smartphone addicts, seem to tell us.

What do we really know about the state of mental health among teenagers today? Suicide offers the most concrete measure of emotional distress, and rates among American teenagers ages 15 to 19 have indeed risen over the past decade or so, to about 11.8 deaths per 100,000 in 2021 from about 7.5 deaths per 100,000 in 2009. …As Max Roser of Our World in Data recently documented, suicide rates among older teenagers and young adults have held roughly steady or declined over the same time period in France, Spain, Italy, Austria, Germany, Greece, Poland, Norway and Belgium. In Sweden there were only very small increases.

Is there a stronger distress signal in the data for young women? Yes, somewhat. According to an international analysis by The Economist, suicide rates among young women in 17 wealthy countries have grown since 2003, by about 17 percent, to a 2020 rate of 3.5 suicides per 100,000 people. The rate among young women has always been low, compared with other groups, and among the countries in the Economist data set, the rate among male teenagers, which has hardly grown at all, remains almost twice as high. Among men in their 50s, the rate is more than seven times as high. …

None of this is to say that everything is fine — that the kids are perfectly all right, that there is no sign at all of worsening mental health among teenagers, or that there isn’t something significant and even potentially damaging about smartphone use and social media. Phones have changed us, and are still changing us, as anyone using one or observing the world through them knows well. But are they generating an obvious mental health crisis? …

According to data Haidt uses, from the U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the percent of teenage girls reporting major depressive episodes in the last year grew by about 50 percent between 2005 and 2017, for instance, during which time the share of teenage boys reporting the same grew by roughly 75 percent from a lower level. But in a biannual C.D.C. survey of teenage mental health, the share of teenagers reporting that they had been persistently sad for a period of at least two weeks in the past year grew from only 28.5 percent in 2005 to 31.5 percent in 2017 …

Overall, when you dig into the country-by-country data, many places seem to be registering increases in depression among teenagers, particularly among the countries of Western Europe and North America. But the trends are hard to disentangle from changes in diagnostic patterns and the medicalization of sadness, as Lucy Foulkes has argued, and the picture varies considerably from country to country. In Canada, for instance, surveys of teenagers’ well-being show a significant decline between 2015 and 2021, particularly among young women; in South Korea rates of depressive episodes among teenagers fell by 35 percent between 2006 and 2018.

Because much of our sense of teenage well-being comes from self-reported surveys, when you ask questions in different ways, the answers vary enormously. Haidt likes to cite data collected as part of an international standardized test program called PISA, which adds a few questions about loneliness at school to its sections covering progress in math, science and reading, and has found a pattern of increasing loneliness over the past decade. But according to the World Happiness Report, life satisfaction among those ages 15 to 24 around the world has been improving pretty steadily since 2013, with more significant gains among women, as the smartphone completed its global takeover, with a slight dip during the first two years of the pandemic. An international review published in 2020, examining more than 900,000 adolescents in 36 countries, showed no change in life satisfaction between 2002 and 2018.

“It doesn’t look like there’s one big uniform thing happening to people’s mental health,” said Andrew Przybylski, a professor at Oxford. “In some particular places, there are some measures moving in the wrong direction. But if I had to describe the global trend over the last decade, I would say there is no uniform trend showing a global crisis, and, where things are getting worse for teenagers, no evidence that it is the result of the spread of technology.” …

To me, the number of places where rates of depression among teenagers are markedly on the rise is a legitimate cause for concern. But it is also worth remembering that, for instance, between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, diagnoses of American youth for bipolar disorder grew about 40-fold, and it is hard to find anyone who believes that change was a true reflection of underlying incidence. And when we find ourselves panicking over charts showing rapid increases in, say, the number of British girls who say they’re often unhappy or feel they are a failure, it’s worth keeping in mind that the charts were probably zoomed in to emphasize the spike, and the increase is only from about 5 percent of teenagers to about 10 percent in the first case, or from about 15 percent to about 20 percent in the second. It may also be the case, as Orben has emphasized, that smartphones and social media may be problematic for some teenagers without doing emotional damage to a majority of them. That’s not to say that in taking in the full scope of the problem, there is nothing there. But overall it is probably less than meets the eye.

Bob Rogers on LNL

A very involving conversation between two men chatting about growing old — and that was 12 years ago. Bob Rogers has just died at 97. It’s a fun listen as Philip and Bob talk about old guys on the radio younger generations have never heard of.

Claire Lehman on house prices

Claire Lehman tweets an extract from her column in the Oz

Since the middle of the 20th century, almost all Australians could expect to one day own a home, as long as they secured a stable income. But the idea that working- and middle-class Australians can expect to own their own homes in their lifetimes is fast becoming a distant memory, much like dial telephones and black-and-white TV.

Sydney is home to hundreds of high schools, with tens of thousands of pupils. A recent analysis shows that any pupil graduating today will have to save for 46 years to afford a deposit for a median house, and mortgage repayments will require 127 per cent of a median salary. Forget about buying a home in order to start a family.

Unless they have wealthy parents to fall back on, school leavers in Sydney will only be able to afford a house in their home town after they’ve retired. But it’s not just Sydney. Across the nation, high-income households in Australia are renting. In 2021, nearly 25 per cent of renting households in Australia had an income of $140,000 or more per year.

In 1996, however, equivalent top income segment households comprised only 8 per cent of renters. There are many different analyses of how and why we got to where we are today. Many on the left blame tax offsets that have created a speculative bubble in property, while some on the right (and the left) blame immigration. But there is one thing most observers of the housing crisis agree on, and that is that the supply of housing has not kept up with demand.

And the reason supply has not kept up with demand has been a change in government priorities over time. To understand how government policy has changed, it’s worth looking at the conditions that created the baby boom between 1946 and 1964. After WWII, the Australian government went on a house-building spree, which made the cost of housing substantially cheaper. Social norms dictated that young couples needed to get married in order to live together – so they married at younger ages.

This led to a boom in babies being born. But before the babies came there was a correlation between houses being built and increasing marriage rates. This correlation between houses being built and marriage rates increasing was not only found in Australia, but in many nations around the world. In the policy wonk journal Works in Progress, Anvar Sarygulov and Phoebe Arslanagic-Wakefield write that “between 1930 and 1960, marriage rates in the US increased by 21 per cent.

Those more likely to marry were in turn more likely to become parents. In this way, the increase in supply of housing fed the baby boom”. It’s worth noting that in Australia, we have not had a housing boom or a baby boom since. Today, government policies do not work to expand the supply of housing, as they did in the lead-up to the baby boom.

They work to restrict supply instead. Research by Peter Tulip, of the Centre for Independent Studies, has shown that planning restrictions in Australia’s capital cities have inflated property prices by as much as 40 per cent. Local councils act like a cartel, artificially restricting supply in the face of increasing demand. This wouldn’t have such a large effect if there were affordable supply outside of the capitals – but there isn’t.

Moreover, in contrast with the 1950s, housing is no longer seen as a form of shelter and security for young families, but is viewed as an investment vehicle. Restricted supply has created the conditions for a speculative bubble where investors do not need to worry about inflated prices, because they know they can still sell and make a profit. Those wishing to actually live in the houses they buy, however, are not driven by profit, and do have to worry about inflated prices.

As urban planner and historian Joel Kotkin warns, this trend underpins an emerging “neo-feudal system” where people are relegated to being lifelong renters, unable to achieve the security that comes with homeownership. If left unchecked, this system will destroy Australia’s egalitarian culture, creating a stratified society where economic opportunity is once again determined by accident of birth rather than work ethic. Some would argue that the age of neo-feudalism is already here.

The latest data on spending released by the Commonwealth Bank shows those aged between 25 and 29 have reduced their overall spending by 3.5 per cent since 2023, and are foregoing essentials such as utilities, groceries and insurance. In contrast, those over the age of 60 (those most likely to own property) are outspending inflation.

Australians aged 75 and older are now spending 6.8 per cent more than they were just a year ago. Compared to this time last year, spending on luxury cruises has increased by 22 per cent. If we do not want to live in a neo-feudal future, where young people are relegated to being lifelong renters, opting for poodles instead of children and video games instead of marriage, we need to increase the supply of housing on a massive scale – and not just in the capitals.

Substack’s business model

And the spectre of enshittification

Here’s a rumination on Substack’s business model by one of its founders. From the start of what was then called Web 2.0 I’ve been fascinated by this explosion of public goods privately provided from Wikipedia to Facebook. As we’ve seen Facebook turned robber baron and, as Cory Doctorow has called it, ‘enshittification’ was the result of its relentless rent seeking. Will Substack go the same way? I doubt it largely because the temptations to do so are nowhere near as big. It relies on empowering writers. Still our co-founder speaks with a somewhat forked tongue because there are already signs that it’s not putting writers in control of accounts where someone ‘follows’ a writer, as opposed to ‘subscribes’. The writer gets the contacts of the ‘subscribes’ and so ‘owns’ them — can port them to another platform. Not so ‘follows’! That’s just like Twitter and Facebook.

Last month, the analyst Ben Thompson quietly marked a milestone: 10 years since he turned on paid subscriptions for his one-man publication, Stratechery.

That milestone has significance to Substack for two reasons.

The first is that the business model that Ben devised for Stratechery inspired the earliest version of Substack. At that time, in 2017, Ben would publish one free weekly article on stratechery.com and then offer readers three more posts a week by email if they subscribed for $100 a year or $10 a month. He accepted no advertising and considered his subscribers his customers. Ben was clearly very successful with that model—Substack CEO Chris Best and I calculated that he was making a seven-figure income from a spare bedroom in his Taipei apartment—and frequently said that more writers should try it. We wondered why more didn’t. …

We guessed that perhaps the biggest reason more writers didn’t do what Ben was doing was just that it was hard. Ben had strapped together various tools, like WordPress, Mailchimp, and Memberful, to constitute Stratechery’s “stack”—we counted 19 tools in total—and it took a lot of work to make them play well together. We wondered what would happen if we made it one-click easy for any writer to try the Stratechery model for themselves. What if a writer could go to a web page, type into a box, click “publish,” and then have money from their readers magically appear in their bank account? …

The Aggregation Era has thus birthed significant new economies, but it has also given the individuals and small teams who rule these platforms almost godlike powers. Today, for good or ill, the fate of the vast majority of the world’s creators rests in the hands of Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Sundar Pichai, and the Chinese Communist Party.

But that simple model that Ben came up with for his one-man publication is a crack in the dam. … If you control your relationship with your audience and can reach them directly, then a fickle autocrat can’t nuke your work with the tap of a button. …

I spend a lot of time telling people that Substack’s real product is its business model. It is a model that is, by careful design, friendly to creators. On Substack, the creators own their relationship with their audience—captured in a mailing list that they control—and all their content, which they can export anytime they want. The creator holds onto the vast majority of the financial value generated on the platform: Substack gets 10%, and the creator gets 90%. We only make money when they make money. Imagine how much money creators could have made in the past couple of decades if the work they did on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok resulted in their getting 90% of the advertising revenue that those platforms instead keep for themselves. …

This new model takes what we have learned from the Aggregation Era and finds a way to blend it with the independence enjoyed by the “sovereign writer”. Anything that takes the power and wealth that was previously concentrated in the hands of a few and distributes it instead to millions of the world’s most creative minds is a step forward for society. My bet is that the Sovereign Creator Era will be better than the Aggregation Era—not just for creators but for everyone.

Academia: another whinger

Substack: Another view

And here’s Vankatesh Rao’s response to the previous article.

I think the substack team is sincere about its mission and doing its best to manage the tensions of being a VC-funded platform while being writer-friendly and growing total readership. The biggest win has been avoiding advertising. But the “sovereign creator” archetype described by Hamish is a bit of dangerous mythologizing (and wanting to be more truly sovereign like Ben Thompson is a bit quixotic). But the other extreme of calling it “share cropping” etc as critics like to is equally inaccurate. Writers here are somewhere in between sovereign and sharecropper. I’d rather realistically acknowledge the main fronts of pragmatic compromise, which I think the team is actually managing well. The alignment is good but not perfect and cannot be. Here’s my take on the state of affairs:

Network effects are real now. The moat against competition that’s most reasonable to grow. I’d strongly support moves like bundling and tokens that allow readers more budget liquidity. This feels values aligned with writers as a group, if not individually. Happy to take a hit personally to grow the pie here for writers still growing/beginning (I’m at a plateau but a decently high one).

Substack now curates discovery which I’ve been wary of, first through spotlight mechanisms and new through notes that reward engagement farming. I think this is fine and reasonable but vulnerable to dangerous temptations. They have to double down on their most energetic revenue drivers (fine). But it’s nearing the knob limit where writers are starting to write for the discovery algorithms/curation tastes (not fine).

Subscriber list data and (in a janky way), Stripe billing relationships are “owned” by writers, including fairly good chargeback handling on our behalf. Good job. Not ideal, but best of a bad set of options. There is no way to do much better in fiat world. Crypto may eventually solve that.

Relationship tools like pausing subscriptions, gift subs, and pricing controls, are all great, but this is where writers need to keep an eagle eye because alignment is weakest.

Copyright is fraught and getting more so with AI training rights. I haven’t looked at the ToS in a while, but last I looked they have fairly extensive optionality to do more, especially on non-paywalled posts. I’m fine with this personally but some genres would face too much risk under this ToS. This will eventually to adverse selection of content.

Product growth vectors in short-form video and swipe-based low-friction graph curation — they don’t bother me at all personally as they do some people. Revenue being linked to longform core adequately balances those pressures for now. But if revenue gets length/form agnostic (eg monetizing notes), all bets are off. Shorter form and infinite scroll UX on app will eat the core.

Finally, perhaps my biggest concern is the gradual dominance of in-app reading and features over both email and web. The closed UX is eating the open protocol. What I’d really like I doubt will ever make sense for Substack to offer or most people to care about — content backup to my own website (not just domain) in the firm of some open-standard static site web framework. But data export is almost good enough. I’ve been thinking of setting up a pipeline for this. Periodic exports —> backup site. But it’s a heavy lift.

Overall, substack is about as good as Web 2.5 can get. But it’s ultimately in “don’t be evil” zone rather than “can’t be evil” zone as the onchain crowd says. I sense substack is mild-to-medium crypto hostile but long-term it feels like the inevitable direction. There are many more complex features and capabilities I’d like but providing them within the substack model will increase misalignment and lock-in. For example, I write lots of series, and on Wordpress I use a series plugin. But I’m wary of asking for a similar feature on substack because it creates more bespoke architectural lock-in and makes export data more idiosyncratic. Which means I’ll stick with the most commodity version of substack on offer. Case in point: My twitter archive is hard to turn into a static website because I used the threading and polls features extensively. So it’s just sitting in my backups.

A Different Sense of Privilege

Privilege today still comes with strings attached, but they are different now, by Steve Lagerfeld

I recently subscribed to Hedgehog review and found this which I quite liked.

In the 1980s, I got to know a man who seemed to be the walking embodiment of privilege. He was an elderly but vigorous WASP, tall and lean, with ancestry in this country that reached back to the seventeenth century. A Princeton man, he had gone into finance and risen to become CEO and chairman of a major regional bank. He had one of those WASP names one can barely resist satirizing, but he had been known all his life by his childhood nickname, Curly.

This was just the first hint that this man was something of an anomaly. (Curly was also, inevitably, almost entirely bald.) Long retired by the time I met him, he had chalked up the expected array of civic and charitable activities during his career. But in retirement he was pursuing with characteristic energy an assortment of more hands-on volunteer jobs. One of them in particular struck me. He was a hospital orderly, pushing carts here and there, assisting patients’ families, and doing various tasks too small or tedious for the nursing staff. “A candy striper,” he joked. As far as I know, he was never asked to empty bedpans, but I’m pretty sure he would have done it.

Where, I have often wondered, does such a spirit of service come from? How could it be revived? Today’s elites are often generous givers of money, yet it’s hard to imagine, say, Bill Gates, a magnificently prolific philanthropist, pushing a cartful of sheets and towels down a hospital corridor. More important, it’s hard to imagine many of the millions of anonymous meritocrats who earn $150,000 a year or more—business executives, technology workers, attorneys, doctors—performing such humble labor. These are the twenty percenters, the new privileged class. Privilege today still comes with strings attached, but they are different now. Our meritocrats are expected to say the right things, embrace the right ideas, and send money to the right causes, but there is no expectation that they should get out in the world and do something to help make it, and its less fortunate inhabitants, a little better. They are free to keep their fellow citizens at arm’s length, and they very often do, especially with loving displays of their superior wealth and status.

The change in the nature of privilege is part of the explanation for the growing sense of grievance and inequality in American society. The sociologist E. Digby Baltzell, the great chronicler and critic of Curly’s WASP aristocracy, made a distinction that is useful for understanding what has happened. In his 1964 book The Protestant Establishment: Aristocracy and Caste in America and other works, Baltzell distinguished between the upper class and the elite. The upper class was Curly’s world—one knit together by inherited wealth, family and community ties, and a shared culture. The elite consisted of the meritocrats—the high achievers in business, politics, the arts, and other fields. The meritocrats’ collective identity, if they had any at all, was limited to the fact that they had all risen to the top of the heap. The two groups overlapped. In Baltzell’s view, the upper class set the tone for society by upholding standards of behavior and ethics and embodying its ethos of service. The key to this system’s success was that the upper class remain open enough to absorb non-WASP newcomers and retain its unwritten authority; Baltzell worried that the WASPs were becoming an insular caste that would dribble into irrelevance, leaving the nation without a moral gyroscope.

The architecture of prayer

Lovely pics.

Heaviosity Half Hour

Hayek dukes it out with the pope

There was an article last year describing a panel held in 1976 on the Role and Self-Image of Intellectuals. Fresh from his 1974 Nobel Prize, Hayek was a panelist, but so too was one theology professor, Joseph Ratzinger? Now the published excerpts from the discussion have been translated by Cody Moser who sent it round to a Polanyi reading group I’m part of.

Anyway, the Hayek passage is fun. I used to think quite highly of Hayek, but have grown weary of his tendentious fixation on all the hazards of excess government regulation of the market — as if there weren’t any from too little regulation of the market. As one time friend and great fan of Hayek John Gray has written ”liberal economy emerges morally naked in Hayek's account of it”. There’s no generosity in Hayek’s thought.

On the other hand I rather like him letting himself go on the question of intellectuals as second-hand peddlers of ideas in this passage. It was always a brilliant expression. And he doesn’t hold back. They essentially know nothing. I know what he means. I agree with him that intellectuals have far too much influence on our public life. intellectuals who know nothing much about anything but who pontificate about all manner of things. He’s really complaining about ideological thinking dominating our lives.

In fact the only thing that gives me pause about the whole thing is that Hayek is the intellectual ideologist par excellence. That’s why a good chunk of the original participants in his 1947 meeting of the Mont Pèlerin Society peeled off accusing him either explicitly or sotto voce of inverse Marxism. To keep the world safe from socialism Hayek proposed a constitution which prevented governments from ‘discriminating’. He never quite clearly explained how much this would prevent, but its main target was progressive taxation, which, as we all know is the height of discrimination. Also all those on welfare or salaries from the state shouldn’t have the vote. Why? Because they were being paid by the state and so had a conflict of interest.

Anyway today things are worse on the “intellectuals overdoing themselves” front. But today they’re third and fourth hand peddlers of ideas. Not only do we have consultants, but we have this new style of thought in which one thinks with Mission and Vision statements and has one’s ‘values’ hanging in the foyer and no-one knows anything, but nice things are said and it is imagined that these then guide the organisation. As Lord Wellington once said, “if you believe that, you’ll believe anything.”

Ratzinger is intriguing in reply. Some of it was unclear to me. But not his concluding passage:

I believe the effort … to establish a discipline of reason even in this area that cannot be objectified, and thereby achieve the communicability of reason and expand reason’s space beyond what can be grasped through science alone, is the [effort] that is urgent today.

Joseph Ratzinger

Announcer:

“The Role and Self-Image of Intellectuals Today” is the topic of our night studio broadcast today in the Farewell to Utopia series.

FA Hayek:

In the house of the hanged man you don't talk about ropes, just as you shouldn't talk about intellectuals in a radio studio. But they are an unmistakable force, even if we are not entirely clear who they actually are. About 25 years ago I tried to define them in English as the “second hand dealers in ideas”, i.e. junk dealers of ideas. And I've found over time that this really highlights a class that sets them apart from other people who are sometimes included among intellectuals.

There are, in my view, three important groups here: there are intelligent people; there are professionals, which very often include very important scholars; and thirdly, there are intellectuals. These are three completely different groups. The intellectuals are people who have mastered the technology of imparting knowledge, but who basically understand nothing, or at least have no knowledge of a subject at all, and who nevertheless owe their prestige not to intellectual achievements, but to the effort to persuade the world to accept the ideas that they have picked up somewhere else. They obviously have a tremendous influence in today's world. One of the speakers made the comment that the intellectuals are unavoidable - I don't know what expression he used - he did not exactly say harmful, but I think although [intellectuals] are unavoidable, they are harmful. It is, in the narrow sense, as I use the word now, a very serious problem.

Because although the intellectuals, as I define them, as “second-hand dealers in ideas”, don't really understand anything, but rather want to make effective ideas that they have come across and whose dissemination is their business, today's world and public opinion is dominated by these professional mediators of ideas. It has become so threatening because it is where unheard-of ambitions arise about what people can arbitrarily do with society. In general, it was not experts who created utopias. The utopias in the sense in which they have been discussed today come from intellectuals in my narrow sense. People who are not experts, people who I would almost say do not belong to my first group of intelligent people, but who belong to the group of professional mediators of ideas. And it is due to the drive of the professional mediators of ideas that there is a constant effort to do everything. The ugly word feasibility has, with some justification, gained popularity recently. The idea that everything is possible is, of course, the modern form of utopia, which is currently being pursued by intellectuals and which is the unheard of field of activity in the special form of democracy that we have today.

A democracy is characterized by the fact that it is a fundamentally unrestricted form of government and that is terribly weak precisely because it is constantly having to buy support from interest groups. Because it is able to satisfy interest groups through special measures, it must do so. So we have an all-powerful tool, an unrestricted democracy, which is promoted by the fact that socialism needs it for its purposes. One could not strive for socialism without unlimited power, which, once it exists, as long as it is run democratically, is exploited by interest groups that can harness intellectuals to claim that they have a special merit or a special claim.

That is the situation we live in today. It worries me terribly because democracy, which in its elementary forms is the only protection of our personal freedom, is actually becoming so discredited that more and more serious people, whom I respect extremely, are becoming extremely skeptical about democracy. This leads to the problem, which seems to me to be the central problem of today, that democracy can only be maintained if we combine it with limited government power. But the prevailing theories believe that democracy, by definition, must retain unlimited government power. All my efforts over the last few years have been directed towards drawing up a plan under which it is possible, indeed, not to assign any other power to the democratic representative authorities, but still to limit their power. If we do not succeed in doing this in some form, I am convinced that democracy will destroy itself. Thank you very much.

Oskar Schatz:

Ladies and gentlemen. I think it was in all of our interests to let Mr. Hayek really speak so fully. It was a moving verdict and thank you from all of us for it. I would like to suggest that we keep the discussion brief and simply take advantage of the opportunity to exchange ideas more often.

Two other speakers were heard from.

Oskar Schatz:

Mister Ratzinger, please.

Joseph Ratzinger:

Yes, in view of the quickly-moving time, I would just like to make a very brief comment that was inspired by Hayek's verdict. [He] made it clear to me that we are all fighting more or less in vain against the origin of the word that Mr. Amery has drawn attention to, and that this silent duel with the actually historically shaped content then leads to further ambiguities. So that it seemed right to follow his verdict and to understand the word again in its original historical form. Manifest is intellectual: this means that people express themselves on general human and moral problems and, in doing so, risk the prestige of their intellectual significance elsewhere. If you look at this origin, it seems to me that Mr. Hayek was not as absurd in his definition as it seemed to be in Mr. Löwenthal's verdict; but to a certain extent that in its initial substance was someone, who based on certain reasons has intellectual prestige but then brings this prestige to bear in the general humane, which is not his profession.

Now I would say that if this is actually the original content of the word intellectual, which always comes through and cannot be eliminated, I would like to evaluate it differently than Mr. Hayek did, because he tacitly recommends, just as Mr. Schelsky did in a similar way, that everyone should retreat to their own field and then everything would be right. And I would say that in the end that's exactly what doesn't work. Because if this happens, that everyone withdraws to their professionalism, where they can really speak competently, then it becomes clear that the actually human questions do not appear anywhere: that they cannot be the subject of science and, if that is the case, the intellectuals have to exclude people incomprehensibly, and that they are, so to speak, scientifically forbidden.

Then the question is, where does this have a place? And that is actually the crisis, which is very closely related to the concept of science and the demands of science. And in this situation, Mr. Schelsky offered us the myth of the simple person as refuge and storage for previously rejected basic values, so to speak. So they are present there, and that doesn't seem to be a solution at all to me, but rather a myth. What characterizes the theologian, who is probably not or cannot be an intellectual at all, is that he did not live among intellectuals, but among simple people, and therefore knows that this myth is a myth. I believe, we are trying to get to the point where we respect and preserve the objectivity of science, which cannot accommodate people as human beings precisely because of the way objectivity has been defined, as a valuable asset. But at the same time we feel our way back to a spiritual objectivity that cannot satisfy these criteria, but conversely also refuses to leave everything that lies outside of it to subjectivity. And I would say that this was actually the legitimate attempt of medieval philosophy and theology: to go beyond mere subjectivity and to establish a discipline of reason here. I admit that [theology] has done this shamefully poorly, and to that extent I am happy to accept everything that Mr. Schelsky says about theologians. I believe the effort that it has pushed: namely to establish a discipline of reason even in this area that cannot be objectified, and thereby achieve the communicability of reason and expand reason’s space beyond what can be grasped through science alone, is the [effort] that is urgent today.

Bernard Williams on linguistic philosophy

This is the first video I can remember posting in heaviosity half hour. I really enjoyed it. HT: Joe Walker.

I liked this passage — which I won’t tidy up from the YouTube transcript:

I think this is a point worth making, that this did make it at Oxford for example, where you and I both studied the subject. I think it did make it enormously valuable form of intellectual training for young people, for students. This insistence on clarity, on responsibility, on paying serious attention to very small differences and distinctions in meaning.

It's a very good form of mental training, quite apart from its philosophical importance. Yes, it certainly had very positive aspects. I think it has to be said that it had some negative aspects in that respect as well.

Yeah, I want to come to those later and not quite yet. Yeah, sure. Yeah. We've talked about the commitment to clarity. But this raises one or two questions in one's mind immediately. For example, the most distinguished of all the linguistic philosophers I suppose most people would agree was the later Wittgenstein. And no one could say that he is clear.

On the contrary, a profoundly difficult philosopher to understand. And I might link this with another point, which you may want to take separately, I don't know. But I'll make it now. I do think that the linguistic philosophers, because of their passionate commitment to clarity, profoundly-- and I mean the word profoundly-- underrated the value of some philosophers who aren't clear, because they're not clear. And the outstanding example there I would say is Hegel. When we were undergraduates, Hegel was dismissed with utter contempt by most professional philosophers, largely because he is obscure. Difficult to read, difficult to follow. It was dismissed as being garbage, rubbish, not worth serious intellectual consideration.

Now that was obviously a profound mistake. In other words, clarity was given importance as a value in philosophy, which I think in retrospect, it can be seen not actually to have. I think clarity turns out to be a more complex notion than perhaps people thought, or some people thought at the time. I think the case of Hegel is complex, because I don't think it just was because he was difficult. It was certainly because he was difficult in a certain way.

For instance, I don't think that Kant ever underwent the degree of dismissal to which you refer. No, no. And I don't think anyone could say that Kant or [INAUDIBLE] language were of a preeminently easy kind at the very least. I think also, one has to add that there were certain historical reasons why Hegel was ideologically suspect to a extremely high degree. I mean, it was thought that a particular-- [INAUDIBLE] totalitarian. Totalitarianism. And he was thought, I think somewhat erroneously, to be connected with as it were, Hitlerian deformations in the German consciousness. And errors of this kind were committed, but of a kind which are not unfamiliar. I think there was a historical context to that.

But you're right in saying that the view of the history of philosophy was very selective and in a way, governed by some concept of clarity. Now there's certainly a difference, if you look at the writings of Austin, and you look at the writings of Wittgenstein. Now it's not because when one says that the difference is the Austin's are clear in a way that Wittgenstein's isn't. I think what one means is, doesn't one, that Austin's is somehow more literal minded than Wittgenstein?

Yeah. Sure. You see, there are very few sentences in the Philosophical Investigations which you referred to which aren't perfectly straightforward sentences. They don't have ambiguous grammar or obscure nouns in them. They-- What is difficult to understand is why he's saying them. That's right. I mean, they contain sentences like "If a lion should speak, we would not understand him."

Yeah. Now that sentence, the point is, the question is, why is it there?

Yeah. And I think that why it's difficult to follow is because of an ambiguity,

a very deep ambiguity, about how far it's harnessed to an argument. In Austin, or any of another of many other linguistic philosophies we could refer to, there are, as in some other philosophers, pretty explicit arguments. There's a good deal of therefore and since and because and it will now be proved in a certain way.

[LAUGHS] Yeah. In Wittgenstein, there are extremely few. I mean, it consists of curious sorts of conversations with himself. And epigrams and apothegms and reminders and things of this kind.

And this is connected with a very deeply radical view he had about philosophy that had got nothing to do with proof or argument at all. So radical was his view about the peculiarity of philosophical problems that he thought that so unlike was his approach to them to that of solving a problems in the sciences that he thought you didn't do it by trying to argue somebody into something. You did it by, as he says at one point, "Assembling reminders of the way we normally go on." Which philosophy tends to disposes us to forget. It's more like trying to get people to see things in a certain way.

That's right. Which works of art commonly do, don't they? Yeah. Plays and novels and so on.

With the suggestion that when we see them in this way, we will see them in a way uncorrupted by the theoretical oversimplifications of philosophy.

Yes. Yes. Whereas now that strain is common to all versions of linguistic philosophy.

It's very important idea that, that the idea of clarity here is connected oddly enough with substituting complexity for obscurity. It's allowed to be complex, because life is complex.

Yes. And while one of the great accusations against previous philosophers is that, although they've been dark and difficult and solemn, what they've actually done is vastly oversimplified. They've produced contrast between appearance and reality or something. But the suggestion is if you actually think about the various ways in which things can appear to be one thing or really be another and so on, or what reality might be taken to be, you'll find that our whole collection of thoughts about this is much more complex than we'd originally supposed.