In Defence of the Bad, White Working Class

And other great things I found on the net this week

In Defence of the Bad, White Working Class

You may remember this essay from 2017. I think I was aware of it and may have read it, but my vagueness shows that it didn’t make a big impression on me — though I would have largely agreed with it. I came across Shannon Burns’ recent book Childhood on browsing a bookshop recently. The little I read of it got through all my filters. I haven’t articulated them before, so let me take this opportunity to do so to myself — and so to you. Here are some filters.

bullshit

reductionism (incl wokedom, victimhood etc)

preciousness or incipient narcissism

jargon filled

So I’m planning to read more — and the reviews are good — of which more below. Anyway, here' are some money passages from the essay.

I suspect that the shame I felt about my parents’ racism sprang mostly from experience: the bulk of my friends were Vietnamese and Chinese, and their families seemed more admirable than mine. My attitude was, therefore, a product of intimacy and experience rather than abstract notions of morality or equality. I had an opportunity, as a child, that my parents—who had grown up poor among working-class whites—never had.

I also had the chance to see myself through migrant eyes, and what I saw was often confronting. Poor whites were scorned by more than a few of the Chinese and Vietnamese migrants I came to know, especially the hard-working, self-sacrificing parents who were deeply invested in their children’s education and upward mobility. They made it clear that I was not the kind of friend they wanted for their sons.

The experience of being deemed undesirable and unworthy even by new Australians is a peculiarly lumpen trial. For me, it was eye-opening. For others, it’s an unutterable humiliation. …

The habits of progressive social and political discourse almost seem calculated to alienate and aggravate lower class whites. I confess that if a well-dressed, university-educated middle-class person of any gender or ethnicity so much as hinted at my ‘white privilege’ while I was a lumpen child, or my ‘male privilege’ while I was an unskilled labourer who couldn’t afford basic necessities, or my ‘hetero-privilege’ while I was a homeless solitary, I’d have taken special pleasure in voting for their nightmare. And I would have been right to do so.

As an aspirational teenage lumpen, I learned to embrace a working-class ethos. It was a simple, experiential lesson: whenever I allowed myself to feel like a victim, I fell into paralysis and deep poverty; whenever I took pride in my capacity to work and endure, things got slightly better. One world view worked; the other didn’t.

Even if I was wronged or oppressed or marginalised, claiming victim status seemed absurd (since I often came across people who were more unfortunate than me), limiting (since there were other, enriching aspects of life to focus on), humiliating (because in the working-class world self-pity is reviled), and self-defeating (because if you allow yourself to think and behave like a victim, you quickly fall into lumpen despair).

At university, I discovered that this ethos didn’t apply. A season of despair would not send middle-class teens spiralling into a life of drug-addled indigence; they could simply brush themselves off and enrol again next year. Strong, class-enforced safety nets meant that self-pity could be accommodated, and victimhood could even form part of a functional identity.

Indeed, the willingness to expose your wounds is another sign of privilege. Those for whom injury has a use-value will display their injuries; those for whom woundedness is a survival risk, won’t. As a consequence, middle-class grievances now drown out lower class pain. This is why the wounded lower classes come to embrace conservative discourses that ridicule middle-class anguish. Those who cannot afford to see themselves as disadvantaged are instinctively repulsed by those who harp on about disadvantage.

I’m sorry I’ll read that again. The above clip was of Alan Partridge narrating the royal coronation, but Her Majesty the BBC, risen to the height of her full pomp, took exception to it and removed it from YouTube. It really is a lot of fun, so you can listen to it below and even play it alongside the normal BBC coverage if you have a VPN

Shannon Burns: and the compulsion to opinion

I wanted to find a review of Shannon Burns’ memoir Childhood that somehow reacted to it without preaching or as a writerly object. Alas I couldn’t find one. Still there’s plenty of telling quotes in Peter Rose’s review:

Eventually, he distances himself from the whole idea of family. ‘I’ve discovered an important truth and it’s all I care about ... No one can be trusted.’ Never is the tone self-pitying or sentimental. The boy is too anxious, too contemptuous because of what is being done to him, or not being done. From the age of five the boy knows he is on his own. Yet somehow he does survive. ‘Nothing is unthinkable for us and everything is survivable. The stakes are always lower.’ The boy withdraws into silence. ‘He only speaks when he wants to. That is his skill: unconditional refusal.’

We marvel at the boy’s repeated exposure. Time and time again his plight should have been recognised. On a few occasions, when something grotesque happens or the boy flees, authorities of one kind or another (police, social workers, teachers) question him about his home life. ‘He knows that they don’t want to hear anything that would complicate matters for them, that no one ever really wants to hear the truth, even if they pretend to, because the truth would make demands of them that they are not prepared for.’

Here’s Adele Dumont:

The impoverished world Burns paints is one rarely depicted in Australian literature. (A notable recent exception is Jennifer Down’s Bodies of Light, a fictional — yet meticulously researched — story of a girl shunted between foster homes and other institutional care settings). Certainly, Childhood redresses this absence. But more broadly, it troubles — and expands — our accepted understanding of childhood, for those who might presume to associate childhood with protection, freedom, and unconditional trust and love. In the particular setting Burns depicts, children can be regarded as burdensome, or even punitive: of himself, he writes ‘I am what happens to people like my mother’ (117). Burns’ account complicates, too, our understanding of motherhood, and maternal love. Mothers, according to Burns, are children’s idols, and synonymous with love. Fathers, conversely, are ‘comparatively replaceable’ (an echoing of Coetzee’s description of fathering as ‘a rather abstract business’(4)). The status of mothers leads Burns to draw this unsettling conclusion: ‘A child fears losing his mother more than the violence she might inflict’ (352). As ever though, Burns with-holds judgement of his (or any) mother: his was never cut out for such a ‘godlike existence’ (355); and mothers, he says are, in the end, ‘prone to all the frailties and vulnerabilities common to us all’ (354).

And one by Burns’s colleagues Adjunct Professor Jennifer Rutherford and Professor Brian Castro at the JM Coetzee Centre for Creative Practice.

The painful heart of this book is its quiet and undemonstrative depiction of becoming oneself, when one has no other to imitate or a standard by which to measure oneself – thus one can only signal distress through defiant gestures, thuggish bullying, and dissociation. This could be a book about the numerous ways a child can turn into a sociopath, about a boy becoming a thug, but instead we witness the boy slowly building an ideational fortress within himself in which to mobilise an ethical self. How can we explain the complexities of character?

Unrelentingly stark, Childhood speaks in whispers and we have to listen closely. There is great character in the writing and the writing itself becomes a character, so that we know it as a quiet friend, unassumingly authentic and modest, astonishing in the rawness of its wounds, but surprisingly intact in its narratorial control. Childhood re-makes the memoir-form like Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, insider and outsider co-existing in the fight for loyalties from which the reader is not exempt.

The best of British manners

The British pride themselves on their manners. They’re important to them in a way that they’re not important to Australians. That doesn’t mean that, on average they treat each other any better. (Apart from anything else there’s their vile and immensely economically destructive class system), but there is nevertheless, often a patina of civility. Never more so than in this really enjoyable and densely informative exchange between Richard Dawkins and Denis Noble. I wrote about this debate a few years ago here — struck by how alike Dawkins’ neo-darwinism was to neoclassical economics, not just in its basic doctrine, but in the authoritarianism with which it imposed its instinct for reductionism. I sent this to Noble and spent an hour with the great man when I visited England. From an old blogpost:

In any event, this is just one string to his bow. If you look at his webpage at Oxford University, you'll see down the bottom a video of his performance with his brother in Oxford Trobadors. From their website:

The Oxford Trobadors take their inspiration from the music of the language, Occitan, in which the 12th and 13th century Troubadours composed. La lenga de l'amor

The language and culture are still alive today in the south of France and parts of Italy and Catalonia. ‘Troubadour’ in Occitan is written ‘Trobador’. The language resembles Italian, Spanish and Portuguese.

With music from medieval to modern, and influences from Rock, Pop, jazz, folk and classical, The Oxford Trobadors play to packed houses. As Ray Noble puts it:

“We put on a show. The group come from a variety of musical genres. We don’t think how a song should be because it is medieval. We think this is how it is, the language, the poetry and the rhythm, the feeling; and so we may use rock, jazz, folk or classic styles to bring the music to life for the audience. Above all we are entertainers.”

There are lots more concerts here. Denis taught himself Occitan when he regularly holidayed in the South of France many years ago and in addition to his first language, English lectures in what sounds like pretty good French and rather worse Italian.

I’ve even made an audio of the same file for you.

And here’s Noble explaining why he’s right :)

One factoid relevant to the French riots

ESG as a puppet show: Policy provocations podcast

There's a spectre haunting ESG, the new trend towards investment funds seeking to consider things other than their financial bottom line. ESG stands for Environmental, Social and Governance. But there's a problem. Often firms are not well placed to improve outcomes beyond their own immediate purview. Thus divestment from high-emissions firms might seem like a good idea, but it turns out to have minimal impact on emissions. This is as one might expect because it simply passes the investment onto investors who don't care about the issue. In fact there's a more powerful reason it might actually be counterproductive which is that starving emissions-intensive firms of funds is likely to depress their investment which they need to reduce emissions. And since the 20% of firms with the highest emissions emit 280 times what the least emitting 20% firms emit, reducing the emissions of the high-emissions firms is very likely to be where the biggest climate change action is going to be.

These are genuine dilemmas but investment firms who seek to target ESG tend not to level with their retail investors that this is what is going on. They're much more likely to do their best and then 'sell' their members some calming PR on how their investments are making a difference. We talk about a left-field way around this dilemma. If you'd like to listen to the audio, you'll find it here.

Hypocrisy led warming

Ken Rogoff on how the developed countries might help with emissions in developing countries — by doing nothing more than taking their own talking points seriously:

Affluent countries’ ongoing efforts to persuade low-income countries to assign a higher value to the global commons than they themselves have done are doomed to fail. Although incentives have aligned in some cases, aided by the falling costs of solar and wind energy, developing economies often find it far more cost-effective to follow in the footsteps of advanced economies and rely on fossil-fuel technologies.

The war in Ukraine has laid bare the developed world’s hypocrisy. For years, developed countries have advised developing economies against using fossil fuels, routinely denying them development loans for gas and oil projects, particularly when intended for domestic consumption. But since the Russian invasion, European leaders have been pressing African countries to ramp up gas production so that it could be converted to liquefied natural gas and shipped to Europe. Germany has even reopened its coal-fired power plants. Moreover, European households and businesses have been granted the same kind of massive energy-consumption subsidies for which African countries were lambasted in, for example, the International Energy Agency’s 2022 annual report. …

Another solution I have advocated in recent years is the establishment of a World Carbon Bank to support technology transfers, provide unbiased country reports on issues related to global warming (for example, monitoring carbon-credit schemes), and facilitate large-scale aid financing. In a recent paper, I proposed funding this new institution through ten-year irrevocable bond donations. But aviation and transport taxes, as proposed by Ruto, are an alternative that might be explored. …

For far too long, rich countries have lectured developing economies about climate change while failing to heed their own advice. Hopefully, innovative proposals such as Ruto’s global green bank idea could foster a more constructive, equitable debate.

Branko on the new colonialism

Interesting piece from Branko Milanovic.

The Prime Ministers of the Netherlands and Luxembourg, presumably on behalf of the European Union, visited Serbia (before going to Kosovo) for less than 24 hours. They were received with the highest state-level honors. In addition, during their super short visit to Belgrade, they found enough time to have separate meetings with the representatives of the Serbian opposition (sitting in the Parliament in Belgrade) who are currently demonstrating in the streets, asking, in my opinion, quite legitimately for government’s much more serious crackdown on violence and crime.

Notice how Prime Ministers of Western countries checking things out with the domestic opposition seems like a normal news item. … The first problem is whether it is appropriate to mix up state-to-state visit with the rest of politics. When countries’ dignitaries visit each other, they do not necessarily imply thereby that they agree with everything their hosts believe, nor that they support the government which receives them. …

The idea of the Serbian president asking officially to meet with the French or even Luxembourgeois opposition strikes one as so fanciful that it laughable. It is a joke. It would indeed be treated as such, were it ever raised as a possibility. But like every joke, it tells us something about the real world. It is that relations between the states have become utterly unequal. Unlike in the period 1960-1990 when the Third World and non-aligned countries were strong and there was at least formally a recognition of equality of states, and in the diplomatic sphere, acceptance of that formal equality, we have moved to the medieval style of inter-state relations where power only matters--even in its ceremonial aspects. No hiding of inequality, but rather its display: prostrate yourself and kiss the edges of my purple robe!

Martin Wolf on inflation again

Last week I posted Martin Wolf’s column on inflation mostly agreeing with it. Here I fully agree with his comment this week that those who say we should not have run monetary policy so loose for so long fail to face up to the alternative — high unemployment.

Finally, what is to be done? The BIS believes in the old-time religion. It argues that we have put too much trust in fiscal and monetary policies and too little in structural ones. Partly as a result, we have pushed our economies out of what it calls “the region of stability”, in which expectations (not least of inflation) are largely self-stabilising. Its distinction between how people behave in low inflation and high inflation environments is valuable. We are now at risk of moving durably from one to the other. Developments over the next few years will be decisive. This is why central banks must be rather brave.

Yet I remain unpersuaded by all tenets of this faith. The BIS argues, for example, that policymakers should have been more relaxed about persistently low inflation. But that would have significantly increased the chances that monetary policy would be impotent in a severe recession. It argues, too, that macroeconomic stabilisation is not all that important. But prolonged recessions and high inflation are at least equally intolerable. Moreover, a stable macroeconomic environment is at the least helpful to growth, since it makes planning by business so much easier.

Above all, I remain unconvinced that the dominant aim of monetary policy should be financial stability. How can one argue that economies must be kept permanently feeble in order to stop the financial sector from blowing them up? If that is the danger, then let us target it directly.

Quite!

A life in ten pictures: Carrie Fisher

I stumbled upon this and found it interesting and moving, but far from ‘must see’ viewing. In case you fancy it.

Another lesson fair play from the English

Australia refuses to play third test unless this clip is looped on the scoreboard: SHOCK!

This is the guy who did his block at Australia for enforcing the rules against Bairstow.

From Red Vienna to renters’ paradise

Thanks to Martin Turkis for alerting me to this article. A lot of ‘long form journalism’ infuriates me. I’m interested in something they’re writing about, but they introduce me to a thousand characters and stories virtually none of which pass the most meagre thresholds of interest, all to convince me that I’m getting some luxury, high(ish)-brow reading experience. Then again, perhaps I’m just impatient :)

In any event, the basic story that you have to donate precious time to extract from this article is interesting. And it’s about perhaps the most important economic transformation that’s happened in my lifetime — the transition we’ve made into a rentier economy.

Auckland, New Zealand, might seem like a more applicable example. In 2016, the city, which has one of the most expensive housing markets in the world, “upzoned” 75 percent of its residential land, increasing its legal capacity for housing by about 300 percent in an effort to encourage multifamily-housing construction and tamp down prices. In areas that were upzoned, the total number of building permits granted (a way of estimating new construction) more than quadrupled from 2016 to 2021. As intended, the relative value of underdeveloped land increased, because it could suddenly host more housing, and the relative value of units in densely developed areas decreased, tempering sky-high prices. But there are limits to what upzoning can do. Often the benefits of allowing greater density are captured by developers, who price the new units far above cost. It doesn’t offer renters security or directly create the type of housing most needed: affordable housing.

That’s what differentiates Vienna. Perhaps no other developed city has done more to protect residents from the commodification of housing. In Vienna, 43 percent of all housing is insulated from the market, meaning the rental prices reflect costs or rates set by law — not “what the market will bear” or what a person with no other options will pay. The government subsidizes affordable units for a wide range of incomes. The mean gross household income in Vienna is 57,700 euros a year, but any person who makes under 70,000 euros qualifies for a Gemeindebau unit. Once in, you never have to leave. It doesn’t matter if you start earning more. The government never checks your salary again. Two-thirds of the city’s rental housing is covered by rent control, and all tenants have just-cause eviction protections. Such regulations, when coupled with adequate supply, give renters a level of stability comparable to American owners with fixed mortgages. As a result, 80 percent of all households in Vienna choose to rent.

The key difference is that Vienna prioritizes subsidizing construction, while the United States prioritizes subsidizing people, with things like housing vouchers. One model focuses on supply, the other on demand. Vienna’s choice illustrates a fundamental economic reality, which is that a large-enough supply of social housing offers a market alternative that improves housing for all.

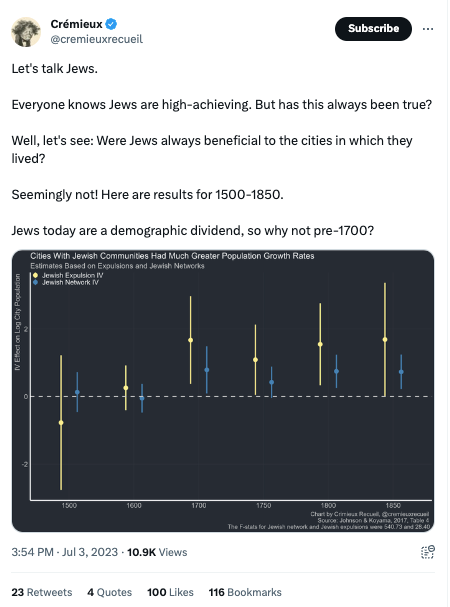

Let’s talk Jews: Fascinating Twitter thread

Load-bearing legibility and the Treaty of Waitangi

An interesting story of how scholarship about the Treaty of Waitangi both debunked the use of it as a constitutional document, but identified the Māori text as a more authoritative record of whatever agreement the Treaty recorded. And since the first message was unwelcome, the process doubled down on the second.

Ross finally got her treaty research published, fourteen years after her first attempt, in the New Zealand Journal of History. According to Attwood, her overriding argument was that it is hard for us to know the intentions of those drawing up and signing the treaty. In her debunking words, the treaty was “hastily and inexpertly drawn up, ambiguous and contradictory in content, chaotic in its execution. To persist in postulating that this was a ‘sacred compact’ is sheer hypocrisy.”

Revealing the treaty to be unfit to serve as a “moral compact, let alone a legal contract” (Attwood’s words), Ross saw her truth as demystifying. But changes in Pākehā/Māori relations meant this was not an argument readers became aware of and valued.

In response to Māori self-assertion, the government established the Waitangi Tribunal in 1975, making the treaty a central “constitutional” document (in a nation without a written constitution). It was not the purpose of Ross’s research to establish how the treaty could work as a morally and politically central two-language text, but this was her research’s fate. Indeed, there is irony in her most iconoclastic assertion — “the Treaty of Waitangi says whatever we want it to say” — because, by the 1970s, Pākehā and Māori were wanting the treaty to say a lot.

In fact, the treaty’s protean character was not the undoing but the making of the treaty as a focus of national life. A non-debunking reading of Ross’s scholarship — a reading that found, in Attwood’s words, “that there were substantive differences between the Māori text and the English texts, that the Māori text constituted the treaty, and that any consideration of its meanings and implications should proceed on that basis” — proved unstoppable.

Martha Nussbaum and animals: someone else is unimpressed

I once attended a Button Lecture given by Martha Nussbaum in which she defended the burqa. I found it bloodless and way too textbooky. Here Clare Coffey finds something similar about her recent book on animals — a subject that has always perplexed me.

In a chapter on tragic dilemmas — dilemmas occasioned by competing and mutually exclusive ethical claims — Nussbaum uses Zulu bull slaughter, Inuit whaling, and Chippewa deer hunting as examples of bad arguments for killing animals to preserve cultures. She describes the Chippewa claim thus:

The Chippewa people hunt white-tailed deer as a necessary part of their material survival and cultural integrity. They claim that venison not only provides essential nourishment, but also fosters bonds of community, and, by ritual sharing with less physically able members of the people, fosters a sense of the equal dignity of all community members. The hunt itself is structured by prayers and rules that are central to the Chippewa belief system.

But Nussbaum tidily sweeps away any potential tragic conflict between her proposed ethics and the life ways of various indigenous groups. At best, she says, appeals to cultural preservation suffer from an intractable problem of “whose voices count”; at worst, they are merely the privileging of machismo. About Inuit whaling she writes:

Most appeals to the values of a culture attend to the voices of the powerful leaders of that group, usually male. They ignore women, critical voices, alienated voices, and so forth. In this case, the young male hunters are being heard, and all sorts of other people with Inuit credentials are not being heard: women, those who moved away out of dissatisfaction with tradition, those who criticize tradition, and so forth.

Aside from the baffling implication that only men are involved in hunting, or that only men have an investment in the continuance of traditional forms of life, there is an odd singling out of the “whose voices count” issue as a problem unique to indigenous political communities advocating for the preservation of tradition (and in many cases, simply lobbying qua sovereign nation for the enforcement of previously guaranteed treaty rights), rather than a problem common to all democracies, all forms of political representation and legitimation — problems that we seem able to live with while defending, say, majoritarian rule as a good.

Indigenous cultures can survive a ban on hunting and re-imagine the goods involved, Nussbaum contends. Thus, “there is no truly tragic dilemma here.” This is true enough as far as it goes. Various Native American cultures survived the Carlisle Indian School founder’s famous dictum, “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” They will doubtless survive “Kill the Indian in him, and save the deer.” …

It may or may not be ethically incumbent upon all people to cease all consumption of animals. But to count the significant loss of remaining avenues of food sovereignty, of the ability to pass on subsistence capacities to the next generation, as mere archaic preference or preening machismo, unworthy even of the dignity of tragedy, is breathtaking arrogance at odds with the humility evinced elsewhere in the book.

Peter Watson

I have a category of people who have written too many books. But, in the immortal words of Groucho Marx — in your case I’ll make an exception. (Writing this I realise that another favourite Grouchoism fits just as well. I have my principles, and if you don’t’ like them, I’ve got others.) Peter Watson has led an extraordinary career, training as a psych (under R.D Laing no less) graduating to journalism, before publishing a string of books on the history of ideas. As the late John Clarke said in his Fred Dagg period, “the Russians experimented with the thickness of the novel and discovered it could become very thick indeed”.

In any event, a friend and colleague — Miguel — recommend I read The German Genius, an experiment with thickness if ever there was one. A terrific 800 page survey of the rise of German high culture from the death of Bach to the ascension of Adolf “No more Mr Nice Guy” Hitler. It takes you on a tour of German philosophy, philology, art, architecture, music and social thought. As the blurb says, it’s a great renaissance — like the ancient Athenian and Italian one that English speakers are only dimly aware of. Anyway, the book leans heavily on secondary literature as you’d expect for someone who was pumping out a substantial book every two to three years. But it seems to me anyway to hit that sweet spot of pithy summaries and examples without dumbing down.

Kant

Here’s what seems to my tiny mind a great summary of the guts of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason.

The sheer intellectual difficulty of the task, to discover what man is and should become, in the absence of a traditional creator or a clear biological understanding—the historical novelty of the predicament—is hard for us to grasp 200 years later. But this difficulty is very evident in the work of Kant, Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel, for example. Many aspects of their thought are hard to grasp, and this is only partly to do with the fact that they were, admittedly, hardly the most elegant of writers. What they were seeking to uncover and describe was difficult; they tried to isolate phenomena that they themselves only glimpsed in moments of lucidity. Nonetheless, “The period of German Idealism constitutes a cultural phenomenon whose stature and influence has been frequently compared to nothing less than the golden age of Athens.” This is Karl Americks, the well-known Kantian scholar, writing in the Cambridge Companion to German Idealism.8 Americks is referring to the overall transformation in thinking achieved by the Idealist philosophers lasting from the 1770s into the 1840s rather than to any particular style. “The texts of German Idealism continue to be an enormous influence on other fields such as religious studies, literary theory, politics, art, and the general methodology of the humanities.”

Idealism was developed in Königsberg, Berlin, Weimar, and Jena. Only Berlin was a city of any size—130,000 or so then. Both Herder and Fichte studied under Kant, later moving on to live near Goethe, who was sympathetic to Kant’s approach. Karl Leonhard Reinhold proved to be an excellent popularizer of Kant in the nearby university town of Jena, and he was followed by Fichte, Schelling, and, eventually, Hegel. They developed their own varieties of Idealism and at the same time forged alliances with the literary giants of the era—Schiller, Hölderlin, Novalis (Friedrich von Hardenberg), and Friedrich Schlegel. They were further augmented by the arrival of a new generation of talented individualists: Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi, Friedrich Schleiermacher, Ludwig Tieck, Jean Paul Richter, August Wilhelm Schlegel, Friedrich Schlegel, Dorothea (Veit) Schlegel, Caroline (Böhmer) Schlegel, and Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt, “a relentlessly creative group.” Most of them moved on eventually to settle in Berlin when the new university was established there (see Chapter 10). Following Napoleon’s stunning victory at Jena in 1806, German Idealism contributed to Prussia’s recovery and in particular to the rise of nationalism and conservatism within Germany.

“German Idealism deserves the attention it has received. It fills an obvious gap generated by traditional expectations of philosophy and problems caused by the rise of the unquestioned authority of modern science.” Idealism had the highest aims, seeking a synoptic understanding of all our most basic predicaments in a unified and autonomous approach. For the Idealists, philosophy should not be a series of ad hoc solutions to abstract technical puzzles. Ultimately, Idealism saw “culture” and “nation” as “higher” moral communities, stretching beyond individualism, the wholesome reflection of Christian duty. It went beyond religion and incorporated politics.

At its simplest, Idealism argues that the bodily organs that allow humans to understand the structure of nature must be phenomena that are “built in” to nature to begin with. It follows from this that there must be limits to reason and therefore limits to what we know and to what we can know. Idealism echoes clearly the Platonic notion of “ideas,” that “there is another level or realm of reality that exists beyond the common sense level in which we normally ‘experience’ life. For the idealists the world exists not quite in the manner that we assume it does…there is a set of features or entities that have a higher, more ‘ideal’ nature.”13 Kant called this realm the “noumenal” realm to distinguish it from the “phenomenal” realm, the realm of phenomena as we perceive them.

Kant’s early works had more to do with science than philosophy.14 Following the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, he produced a theory of earthquakes; he also conceived a theory of the heavens which predated Pierre-Simon Laplace’s nebular hypothesis—that the solar system was formed by a cloud of gas condensing under gravity. But it is as a philosopher that Kant is chiefly known, and in his philosophy he identified—and then sought to clarify—what were for him the three most important questions facing mankind. First, he addressed the problem of Truth: How do we know the world and is it a true representation? Second, Goodness: What principles should govern human conduct? Third, Beauty: Are there laws of aesthetics, conditions which nature and art must satisfy in order to be beautiful?

Kant addressed the first question in what is generally regarded as his most important book, Kritik der reinen Vernunft (Critique of Pure Reason), published in 1781 in Riga. It came after ten years of rumination and reflection—years that, as more than one critic has observed, did not improve his writing style. Kant rarely seems to have thought it necessary to give illustrations of his abstract points, never imagining that it would make his arguments easier to follow. His starting point was what for him was the crucial difference between two kinds of judgment. When someone says: “It is warm in this room,” what he or she really means is: “It seems to me warm mathematical proposition that the sum of the angles in a triangle are equal to two right angles of 180 degrees is correct irrespective of the person making the measurement. It is true, as Kant put it, without reference to experience: it is universally true and “from the first” (a priori).

How does this difference arise? Kant’s answer was that the shapes of geometry are “ideal constructions” of our mind. Geometry is in effect a creation of the human mind, insofar as no one has ever seen a “pure” triangle, say, without any other attributes. Such a phenomenon does not—could not—exist. The figures and triangles that we see about us are only imperfect representations. This, for Kant, was very important for it showed that cognition of the world, how we know the world, “need not necessarily be the product of experience, of the mere functioning of our senses.” Experience is the raw material but those experiences only become fully intelligible through the “productive activity” of the mind. Thought creates concepts.

Kant is saying that we do not have in our heads, as it were, an image of the world “out there” instead we have an idea of how it appears to us, according to the laws of our intellectual make-up, which are present a priori, and which—invariably, inevitably, and necessarily—shape experiences a posteriori. Because of this we can never know anything “in itself.”

Kant identified several a priori aspects of our minds, of which the two most important were space and time. He was saying that we are born with an intuition of space and time, we understand them without experiencing them, in advance of any real sensation. Space and time, he argued, are not properties belonging to objects, but are merely subjective ideas we impose on them. Kant thought his case was proved by our idea that space is infinite, “which no one can experience or demonstrate.” Though we can imagine space with nothing in it, we cannot imagine the absence of space itself.18 The same is true of time. As with space, we can imagine not much happening over a certain period but we cannot imagine the absence of time itself. Time as we understand it—as with space—has no beginning and no end, it is infinite. It cannot stem from experience.

Kant’s underlying point was that our minds are “living, actively operative organisms,” not passively receiving information from without, through the senses and summed through experience; instead our minds shape our perceptions according to their own laws. He didn’t stop at space and time but identified twelve categories or laws of thought, which shape how we understand the world. Among them he included “unity,” “multiplicity,” “causality,” and “possibility.” “Things in themselves possess neither unity nor multiplicity…we ourselves, through the operation of our understanding, combine certain impressions a priori into a unity or multiplicity (trunk, branches, twigs, leaves, into the concept tree).” Kant did not say that there is no connection between the outer and inner world. Scientific experiments, for example, proved that there is a close connection. Insofar as we are able to manipulate phenomena in ways that others can replicate, “There must exist common ground between the sensuous world and the understanding.”

This approach raised an intriguing set of questions in the world between doubt and Darwin. For example, where did it leave the question of God? Was what Kant was saying evidence for a metaphysical world that exists beyond reality, beyond our senses and our understanding? Many people cannot imagine a world without God, just as they cannot imagine a world without space, so did that make God an a priori intuition as real as space or time? Kant thought that the intuition to recognize the connection between external phenomena led to the idea of the universe, the absolute whole. This idea of the “whole” carried with it the further idea of an ultimate cause of the whole. By the same token, the fact that the inner structures—or laws—of our minds form a whole, a connected, interlocking, understandable whole, produces an equivalent idea, holding everything together—this is the concept of the soul. From there it was no great jump to say that the inner and outer worlds, soul and universe, point to an ultimate common basis, embracing both. The entity that “ holds and unites” everything we give the name of God.

It is not quite as simple as that. The universe might be an “absolute necessity,” given the structure of our minds, but we cannot forget that the universe is not an object that we can experience in its entirety, but merely an inference—and this produces its own problems. For example, the very concept of a universe implies that it has a boundary. If that is so, what is there beyond this boundary? How then can the universe be infinite? The universe, in other words, is a “contradictory and hence impossible idea.” The same argument applies to time and the ideas of “before” and “after.” Time without end is simply inconceivable; so is an end to time. “Space and time are simply forms of our thought.”

In analogous fashion, for Kant the existence of God can never be proved rationally. God is a notion, our notion, like space and time, and that is all. “God is not a being outside me, but merely a thought within me.” He was careful not to deny the existence of God—instead he denied our cognition of Him (for which the king reprimanded Kant). God, he argued, can be conceived only through the moral order in the world. Kant thought that humans “are compelled” to believe in God (and immortality), not because any science or insight leads them in that direction but because their minds are built that way.

Thx