If we tolerate this, our children will be next

and other highlights on the net in the week ending April 23

Hi Nicholas

This is to thank you for the weekly sample of such a large range of ideas. I turn 95 this coming Wednesday, sharing April 20 with Hitler as with many more worthy people.

If we tolerate this, our children will be next

Dennis Glover, a subscriber to this newsletter and author of the novels The Last Man in Europe and Factory 19 sent me this op ed last week.

Question: Given that history repeats, what year is this?

Fifteen months ago, when Donald Trump’s rag-tag militias stormed the Capitol building in Washington D.C., I thought for a moment we might be living in 1923, witnessing the rebirth of western fascism. Such were the similarities with Hitler’s putsch of that year. Six years more, I thought, and we’ll be in 1929 at the start of the Great Depression, and then just one more low, dishonest decade to global war.

History repeats, but maybe faster than we imagine. When President Putin’s divisions invaded the Ukraine some fifty days ago, my mind was instantly back in 1936. Just as Putin has tried to do, elements of the Spanish Army led by General Francisco Franco, attempted a coup against the liberal Spanish republican government, thinking its military takeover would be fast and surgical. When it failed to succeed overnight, an attempt was made to quickly overwhelm the major cities, including Madrid and Barcelona. The republican defenders dug in and fought stubbornly. The attacks were beaten back, with fierce fighting on the outskirts of the cities. Territory changed hands several times until the cities were saved – for a while.

Is this starting to sound familiar? 1923 became 1936 in no time at all. But the historical resemblances only get worse.

Supplied and piloted by mercenary flyers from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, the Francoist air force bombed republican-held cities in a brutal terror campaign. The dead bodies piled up, including the dead bodies of children. This gave birth to an evocative image: A poster featuring the photograph of a dead child against the backdrop of a formation of bombers, and below it the following: ‘If you tolerate this, your children will be next.’

Music lovers may recall that the British rock band the Manic Street Preachers made that slogan it into a hit song in the late 1990s.

This seems to me the depressing but empowering message for our times.

J'Accuse: Jonhathan Haidt on Social Media

A long, well-considered article. Unlike Haidt, I’ve always thought it important to stress the continuity between the media environment between and after social media. My go-to factoid is that between 1968 and 1988 the average length of presidential sound bytes on national TV network news went from 48 to 9 seconds.

Still, Haidt makes a devastating case.

We can never return to the way things were in the pre-digital age. The norms, institutions, and forms of political participation that developed during the long era of mass communication are not going to work well now that technology has made everything so much faster and more multidirectional, and when bypassing professional gatekeepers is so easy. Yet American democracy is now operating outside the bounds of sustainability. If we do not make major changes soon, then our institutions, our political system, and our society may collapse during the next major war, pandemic, financial meltdown, or constitutional crisis.

I note one of his three core proposals. “We must harden democratic institutions so that they can withstand chronic anger and mistrust” a subject which, as I’ve always thought needed to be addressed, but was never front of mind for anyone. But I did what I could.

And here’s the podcast of the article with Andrew Sullivan (which I’ve not listened to yet).

Can Algorithmic Recommendation Systems Be Good For Democracy?

A while back I wrote a post on what I called the middleware of democracy. It was too long and verbose. This is perhaps a more lucid, and certainly more recent discussion of the same kind of idea.

Expect to hear more about ‘centripetal’ and ‘centrifugal’ institutions from me. {Hint: representation by competition (elections) is, as we’re seeing, centrifugal, whereas representation by sampling (juries) is centripetal].

An alternative “for good”: Bridging-based ranking

An example of [a better recommender algorithm would be one] that rewards content that bridges divides. Such a bridging-based ranking system might infer societal divisions, and reward content that decreases the extent of those divisions.

For example, imagine two potential articles that Twitter’s feed might show someone about immigration. One appears likely to increase divisions across opposite sides, another is more likely to decrease divisions. Engagement-based ranking would not try to take this into account—it simply factors in how likely one is to engage or stay on the app—which is likely higher for a divisive piece that leaves users ranting and doom-scrolling. Bridging-based ranking would instead reward the article that helps the opposing sides understand each other—that bridges the divide.

Another way to think about this is that engagement-based systems can be thought of as a form of “centrifugal ranking”—dividing us into mutually untrusted groups; in contrast, bridging-based ranking is a kind of “centripetal ranking”—helping re-integrate trust across groups. If we can do it well, the implications are staggering. Bridging-based ranking would reward the ideas and policies that can help bridge divides in our everyday lives, beyond just online platforms. Moreover, it can help change incentives on politicians—many of whom have been forced to play to whims of the engagement-based algorithms. It might even make journalism more profitable and more meaningful—no longer burying fact-based reporting under a sea of cheap sensationalism, and rewarding empathic and bridge-building journalistic practices. Finally, it may dramatically reduce the need for moderation. If division and hate are no longer rewarded with attention, there will be much less of it!

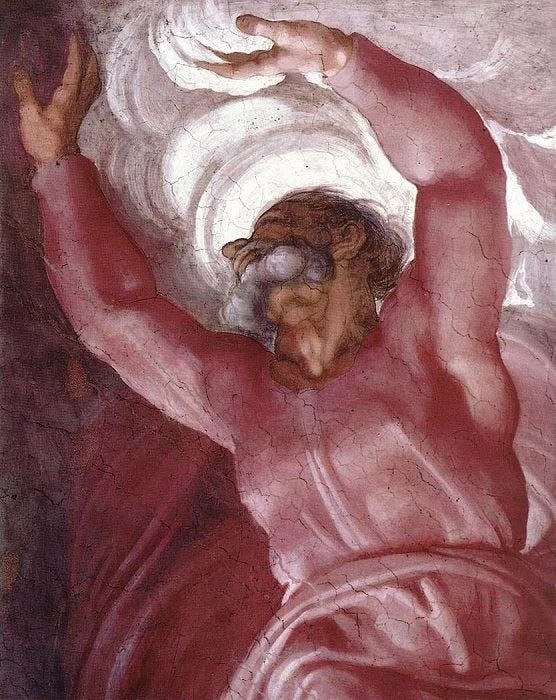

Is this picture a self-portrait?

Of the great figures of the High Renaissance, Raphael died young and Leonardo was getting on when it got going (I learned that the High Renaissance ‘started’ in I think it was 1498 with Leonardo’s painting of the last supper). Only Michelangelo got through to the end of the High Renaissance and led the way into Mannerism. Learning about this in school, I could see the difference in the styles (Mannerism was much less to my taste). No doubt they told me that Mannerism reflected the unnerving beginning of the reformation. Within a decade or two of Luther’s nailing those 95 theses to the church door in Wittenberg in 1517, things looked very different and much darker.

Being older now and slightly less dim-witted, I can understand that idea of a darkening time. I’m thinking you probably can too. Who knows if these guys knew they were living through a golden age as they sipped lattes during the High Renaissance (OK, there weren’t any lattes, but I’m hoping they ate well). But whatever was on Michaelangelo’s mind as he painted the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel, it sure was different to what was on his mind as he painted the ceiling. In any event, I came upon this essay on a commercial art site, the principal purpose of which is to sell stuff. So I expected a bit of a puff piece. But it was better than that. Ending in this paragraph:

The world as Michelangelo left it was not the world that raised him nor the world that welcomed him. It was far bleaker and colder. And as he reflected back over his lifelong work, the reader catches a glimpse of a man whose love of beauty led him increasingly to eschew even the joys of his own craft, turning not towards his creations or legacy but rather toward the image of love, found in the Church he had, however well or poorly, at least attempted to serve. At the end of the day, it may be that, beyond even his technical prowess and awe-inspiring artistic vision, viewers are drawn to Michelangelo’s work in part because of his own loyalty to the things he loved – art, Italy, his faith – even in their apparent brokenness.

There’s More to Authoritarianism Than Cults of Personality

A study of strongmen misses deeper reasons for democratic collapse.

A good, if too long takedown of Gideon Rachman’s latest wheeze. I’ve not read it and won’t, but it’s worth reminding oneself not to take unserious efforts too seriously.

When it comes to sources, moving almost exclusively among elites has its limits …Instead of vivifying details, we get one too many anonymized quotes stating the obvious: “As one prominent Beijing academic complained to me,” he recounts, “‘We are increasingly living in a totalitarian state.’”

The rare critique with bite in these pages comes from, of all places, Boris Johnson’s Eton housemaster. “Boris seems affronted when confronted with what amounts to a gross failure of responsibility,” he writes to the Johnson parents. “I think he honestly believes that it is churlish of us not to regard him as an exception, one who should be free of the network of obligation that binds everyone else.” …

Since Rachman has written about, and in many cases met, the leaders in this book, he could have examined his own analytical errors more closely, alongside those of his peers. The potential of that far more interesting book, focusing on media discourse about this century’s autocrats rather than the men themselves, haunts this one. …

Absent real guiding questions or answers, this book ends in a hopeless place. The solutions presented in The Age of the Strongman can be summed up as: Wait. Wait for elderly leaders to finally step down or lose (as Netanyahu did, after 12 years), or for an economy to collapse (as Russia’s might, under the weight of sanctions and a turn away from its fossil fuels), or until the United States somehow saves the day. What else, indeed, can the subjects of increasingly fragile liberal democracy do against such enormous tides?

Development Economics Goes North: Dani Rodrik

When economists talk about global convergence, what they usually have in mind is that developing economies grow more rapidly than advanced economies, and the incomes of the world’s poor rise to levels in richer economies. The irony nowadays is that we are experiencing downward rather than upward convergence. Developed countries’ problems increasingly resemble the problems found in poor countries. The models and frameworks used to study developing economies are increasingly relevant to the problems confronting rich countries.

The case for the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Habsburg federalism could have worked if not for an assassin's bullet

Fascinating post from Matt Yglesias

In today’s light, the idea of the Habsburg realms evolving into a multi-lingual democratic entity doesn’t seem particularly absurd. The empire wasn’t doomed by its diversity of linguistic groups — it started and then lost a major war.

In Matt’s alternative history:

The whole empire, in fact, has a strong economic logic. Sentimentally, the Italian-speaking people of Trieste might enjoy the idea of national union with their fellow Italophones. But Trieste connected by rail to Ljubljana, Graz, Vienna, Bratislava, and beyond is a major port and commercial center. … The city’s bourgeois classes know that they’re better off inside the empire than out.

Without the destruction and devastating disruption of trade due to the war, Europe is considerably richer. And by midcentury, … far from a feudal relic, the empire starts to seem progressive and modern. With Jews as a national constituency for a polyglot empire, the authorities in Vienna become increasingly philosemitic with strong Jewish political representation. And while the empire is not friendly to Polish or Ukrainian nationalism, it’s also not in the business of suppressing minority culture groups the way the German and Russian empires are.

If you want innovation, you need inefficiency

Frontier, a subsidiary of Stripe is aggregating funds of firms seeking to buy carbon offsets.

The company is taking an intentionally non-efficient approach to buying carbon removal. Frontier, has set a maximum amount that it will spend to remove a ton of carbon. On average, Stripe paid a “couple hundred dollars a ton” to remove carbon dioxide, Ransohoff said, but its purchases ranged from $75 to $2,052 a ton.

In the 1950s and ’60s, the US Government promised to purchase the fastest semiconductor from any company that could produce it at essentially any cost. Small firms could explore experimental new techniques and break even just by selling a few chips to the government. A similar program sought to help commercialize solar panels. But this was far less successful, in part because it sought to buy the most efficient panels—which meant, effectively, the cheapest. Instead of supporting a vibrant ecosystem, this program encouraged companies to compete one another out of existence.

The end result of those two policies is that America remains a major player in semiconductors but hardly makes solar panels anymore—even though both underlying technologies were invented here. Of course, carbon removal is a long way from matching the economic importance of either of those industries. But if it gets there one day, Frontier could be a crucial part of its story.

Labor spotless: the Coalition disgraceful

Yes folks that's barely an exaggeration — read the tweet thread

And in response to this reply

I tweeted this:

Democratic government is built on generations — centuries — of time-honoured practice solidified into convention. It's true that conventions change over time, but as we’re being forced to relearn, democracy is a dead duck without some notion of independence sitting both at the centre of our system of government (to provide advice and administration) — and then sitting outside it (to inquire on behalf of, and inform the demos).

And independence is a two-way street. I'm confident(ish) that Stone took his obligations under that convention seriously as did Hawke. And that's as it should be.

Of course, these conventions are not absolute standards, but I'd be a little shocked if you didn't agree with the tenor of my comment, that the Coalition performance on this score has been a disgrace, involving, as it has, the removal of one or two perfectly good Labor appointments that perhaps they felt they couldn't trust with the overwhelming majority being excellent public servants dedicated to doing their duty

You can't have a convention designed to stabilise and improve our government that only one side is committed to.

Meanwhile in an ailing democracy near you …

How to survive a campaign and not sell your soul

Mark Textor, co-founder of one of the most successful political strategy consultancies in the English speaking world (without whom David Cameron, John Howard, John Key, Tony Abbott would not have been as successful as they were) offers his thoughts on campaigning. We’re connected on LinkedIn where he republished this column from 2012. He starts campaigns he runs spending the best part of a day at a suburban food court in a marginal seat. The empiricism and humility of this practice seems like a good clue to its success. Who knew? Amazing what really trying to listen does for you in politics, even if in the end your own objectives, like your opponent are manipulative.

Six: Look after your soul. The corruption of the soul happens in small steps, not big leaps. If you have a family, keep a picture of them in your wallet or on your screen. When you have a spare minute, call a loved one or mate. When you have a spare day, spend it with loved ones, not feeding your own need for career recognition by being a stayer in campaign headquarters just to be seen. They are the ones who are most likely to get your mindset out of the campaign bubble, to help you understand what's happening in the real world. You are not more important than your family, friends or the community you serve. Nor is any campaign.

Of course others say the same, but the question is how much they mean it. In my experience conservatives in politics are less likely to think they’re plying some special trade which is more important than other things one can do with one’s time — you know like bringing up kids for instance.

On the other hand, I’m pleased he managed to keep his soul intact while he ran the campaign to abolish carbon pricing in Australia — something that I’d expect well over half the parliamentarians who voted for it knew was disastrous, for their country and their world. It is now costing Australia’s budget over $10,000,000,000 each year. I guess you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs.

Confucius and the Whistleblower

Interesting article from the ambitious new(ish) e-zine Palladium. It caught my eye particularly because I’ve been drawing attention to the ancient Greek political principle of parrhēsia. It is often translated as “freedom of speech”, but it’s subtly and profoundly different to that. Where free speech imputes speech rights to individuals, parrhēsia references a relation. It implies the citizen’s or individual’s duty to speak boldly and truthfully, first to themselves and then to power and the reciprocal duty on power to overcome their vanity so as to listen. Also in ancient Athens, ‘power’ can include the demos. Thus, at least as Plato presents the story, Socrates’ performance at his trial was parrhēsiastic — the decision of the citizens’ constituting the court not so much.

In any event, this article compares the modern adulation of whistelblowing with Confucius’s concern that those who find fault with power remonstrate with it, rather than defect and blow the whistle. I’m not too sure the two things should be contrasted so strongly — with whistleblowing correspondingly deprecated — but the analogy with parrhēsia made it an interesting article for me.

What makes remonstrance work in practice? The foundation of Confucius’s social philosophy is that relationships are the central element of functional institutions. When relationships become adversarial or low-trust, it is only a matter of time before customs or laws start to decay as well. Laws can never substitute for proper, virtuous relationships.

Louise Milligan on her son’s Autism

The idea that autistic people are not feeling deeply, not analysing their surroundings, their social dynamics, their peers, is also off the mark. I will never forget a teacher telling me about an autistic boy who had been non-verbal all his life being given a communication tool at the end of high school. With it, he dictated an essay about his life. It was, by her account, profoundly perceptive. His teachers were floored. He critiqued the various therapies he had been given with maturity and wry scepticism no one knew he possessed. He joked about his parents. He observed his social situation with great clarity. And this was someone who had barely spoken a word in his life. In the old days, he would have been considered “retarded”.

It is no longer cool to call someone a retard. It is no longer acceptable to name-call. We’ve moved past the era when it was assumed that cold “refrigerator mothers” created their children’s autism. But here’s the thing, the refrigerator mothers are gone, but refrigerator children remain. People keep assuming that to be autistic means to be cold, aloof, out of touch with humanity. Somehow it’s seen as OK to stereotype people with autism. It’s not. It hurts those people and everyone that loves them. Next time someone does it around you, call them on it.

Dispatches from the Kingdom of ‘Yikes!’

(My renaming of the Ukraine section of this newsletter)

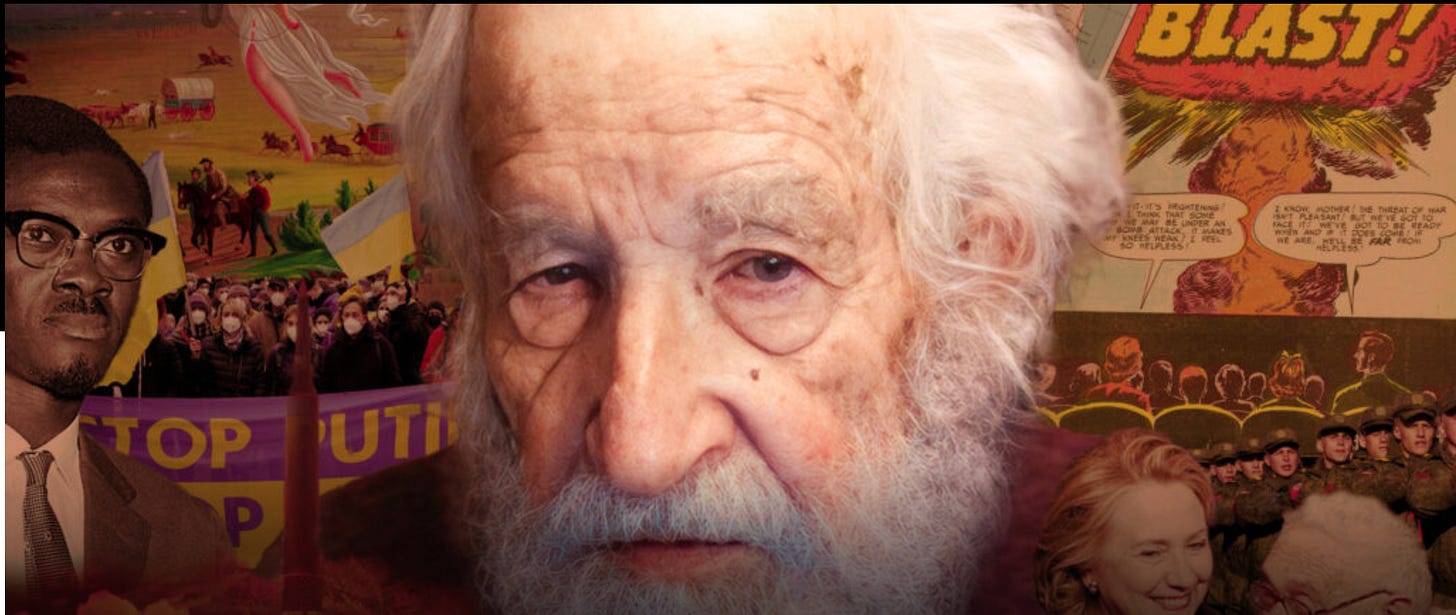

One of the sad things about our species is that everyone’s so damn sure of themselves. We arrange ourselves into little culture wars and we’re oh so sure we’re right — morally and in our analysis. I guess that goes at least some way to explaining how we get into wars. Anyway, at the head of this week’s crop is Noam Chomsky who’s position is that we should be trying to end the war as soon and with as little loss of lives and treasure as possible.

Noam Chomsky and fighting to the last Ukrainian

In this world, there are two options with regard to Ukraine. As we know, one option is a negotiated settlement, which will offer Putin an escape, an ugly settlement. Is it within reach? We don’t know; you can only find out by trying and we’re refusing to try. But that’s one option. The other option is to make it explicit and clear to Putin and the small circle of men around him that you have no escape, you’re going to go to a war crimes trial no matter what you do. Boris Johnson just reiterated this: sanctions will go on no matter what you do. What does that mean? It means go ahead and obliterate Ukraine and go on to lay the basis for a terminal war. Those are the two options: and we’re picking the second and praising ourselves for heroism and doing it: fighting Russia to the last Ukrainian.

And yes, we can pursue that policy with the possibility of nuclear war. Or we can face the reality that the only alternative is a diplomatic settlement, which will be ugly—it will give Putin and his narrow circle an escape hatch. It will say, Here’s how you can get out without destroying Ukraine and going on to destroy the world.

We know the basic framework is neutralization of Ukraine, some kind of accommodation for the Donbas region, with a high level of autonomy, maybe within some federal structure in Ukraine, and recognizing that, like it or not, Crimea is not on the table. You may not like it, you may not like the fact that there’s a hurricane coming tomorrow, but you can’t stop it by saying, “I don’t like hurricanes,” or “I don’t recognize hurricanes.” That doesn’t do any good. And the fact of the matter is, every rational analyst knows that Crimea is, for now, off the table. That’s the alternative to the destruction of Ukraine and nuclear war. You can make heroic statements, if you’d like, about not liking hurricanes, or not liking the solution. But that’s not doing anyone any good.

Chomsky references the conversation below which I recommend. Or on Soundcloud if, like me, you are offended by the idea of watching a person talk for 50 minutes, rather than just listening to them.

I’m not sure whether I’d put it the way Chomsky did, but it’s a reasonable perspective. It brought forth a torrent of abuse — such as this piece from the usually excellent Noah Smith who tendered it as Exhibit One in the loathsomeness of American socialism. He even trotted out Chomsky’s playing down the crimes of the Khmer Rouge — which is an ugly story but largely irrelevant here since Chomsky is not excusing Russia. Still, Chomsky himself chooses to express himself with a confidence he shouldn’t really have given how difficult the situation and the judgements it calls for is. I’d like to see more humility because it would better reflect how confident anyone should have given the fog of this situation. But I’d also like to see people trying to persuade rather than abuse each other. Oh well, as they say in Hollywood, “that’s entertainment”.

I liked this take on it by Freddie deBoer — even if it was pretty trenchant itself.

People Just Want to Feel Good About War Again

you can support a war while thinking critically about its public perception

I haven’t seen an insistence on groupthink like this since the post-9/11 world. And what’s particularly dark for me is that people who define themselves by championing dissent and free speech - this whole constellation of anti-social-justice-hegemony dissident opinion publications and personalities - have been no less likely to demand that everyone get onboard with the dominant narrative.

You can think that Russia is clearly acting in an unjustifiably aggressive manner and that Ukraine has a right to defend itself, as I do; you can support sending further American arms and money to the Ukrainian government; you can think that NATO and EU behavior have nothing whatsoever to do with Russia’s actions; you can think that Russia’s motivations are pure mustache-twirling evil with no justifications in national security or realpolitik; you can even argue that the United States should send troops and get into a hot war with Russia on Ukraine’s behalf - you can believe all of those things and still find the current state of the discourse to be disordered and unhealthy. You can believe all of that stuff and still argue that the intense social mandate against dissent and hard questions is ugly and unhelpful.

Fukuyama on Ukraine and global authoritarianism

Quite a good read.

I do not know that I can predict the future. I can tell you what I hope could be a possible outcome, which is that Putin will be defeated pretty decisively. In turn, that will take the wind out of the sails of the global authoritarian populist movement that he is the leader of, and there will be a rebirth around the world of belief in liberal democracy.

Putin’s World War Z

The main feature of this Western condition is constant belatedness. The West has always been too late, incapable of acting ahead and instead just reacting to what has already happened. As a Ukrainian joke went at the time, “While the European Union was taking a decision, Russia took Crimea.” Then as now, Ukrainians wondered, “What is the West’s red line? What will compel the West to act instead of waiting and discussing when to intervene?”

Signs of escalation to full-fledged world war are not yet evident. But what has already become crystal clear is that this war is the war of the worlds, and now is the moment of truth for our whole world. “Z” is the end of the alphabet, a hollow symbol, followed by nothing – no eternity, just emptiness.

The intricacies of Russia and the middle east: the view from Syria

Wheels within wheels.

Putin knows his ambitions exceed his means. He is therefore obliged to form alliances with partners of dubious reliability. …. It draws Putin into both co-operation and rivalry with other regional powers that have just as much appetite for interference in their neighbours’ affairs—Turkey, Israel and Iran.

Since the interests of those three countries are opposed to each other, Putin has mastered the art of managing his agreements with each. It is a game in which each player forms fluid agreements based on the limits of its individual power. Syria provides the clearest example. Russia’s original intervention could not have succeeded without the massive deployment of Shia militias trained by Iran. But Iran’s presence in Syria alarmed Israel. Putin therefore gave tacit agreement to Israeli air raids on Iranian sites in Syria. With Turkey, Putin’s game is equally risky. In the Syrian conflict Putin and Erdoğan have backed opposite sides—just as they have in the Libyan conflict—but they have managed to reach an agreement that prevents either of them from trying to eliminate the other from the board.

Israel became an important strategic partner when the Cold War ended, particularly as a supplier of military technology such as drones. But Israel has also supplied military technology to Ukraine. That had to stop when the Russian attack was launched. Otherwise, the tacit agreement—whereby Moscow did not intervene when Israel attacked Iranian sites in Syria—would have been threatened.

Propaganda Inc

Karl Marx & the birth of modern society

Meanwhile . . .

Opinion: Another Species of Hominin May Still Be Alive

OK, I can’t help myself. A bit of scientific linkbait.

In 2004, the scientific world was shaken by the discovery of fossils from a tiny species of hominin on the Indonesian island of Flores. Labeled Homo floresiensis and dating to the late Pleistocene, the species was apparently a contemporary of early modern humans in this part of Southeast Asia. Yet in certain respects the diminutive hominin resembled australopithecines and even chimpanzees. Twenty years previously, when I began ethnographic fieldwork on Flores, I heard tales of humanlike creatures, some still reputedly alive although very rarely seen. In the words of the H. floresiensis discovery team’s leader, the late Mike Morwood, last at the University of Wollongong in Australia, descriptions of these hominoids “fitted floresiensis to a T.” Not least because the newly described fossil species was assumed to be extinct, I began looking for ways this remarkable resemblance might be explained.