I Teach the Humanities, and I Still Don’t Know Their Value

And other fine things I found in the last few days

A magnificent picture!

I Teach the Humanities, and I Still Don’t Know What Their Value Is

I was once appointed to a body that was supposed to be producing some ‘vision’ for ‘the arts’. The minister said he was putting me on because I’d add rigour. By which I presume he meant that I bought into the lame nonsense about the arts paying for itself — you know because it makes your city more ‘liveable’ (which it does) and that it makes people more ‘innovate’.

It’s hard to see how it would, but it’s not completely implausible. But if making people more ‘innovative’ is what you’re about, why not try to do that! Another good racket for the arts is the ‘disadvantaged’ racket. It’s not that the ‘disadvantaged’ can’t benefit from the arts. They can. But if you were serious, wouldn’t it be a two way street with the deliverers of the arts learning as much as the ‘disadvantaged’ do. If it was a real adventure rather than the next lame upper middle class boondoggle I’d be all for it.

Anyway, I reckon the arts — in so far as they haven’t been given over to agitprop or hollowed out with tendentious themes (ideological and otherwise) are a Good Thing. That’s why we should fund them. That’s why Lorenzo Medici funded them. Oh well, he probably didn’t. It was probably social display, but somehow the culture he inhabited managed the alchemy by which his money and ego was transformed into Great Art.

Anyway, here’s popular philosopher Agnes Callard having a go at similar themes.

We have been issuing a steady stream of defenses of the humanities for many decades now, but the crisis of the humanities only grows. … We humanists keep on trying to teach people what the value of the humanities is, and people keep failing to learn our lessons. … As a humanist — someone who reads, teaches and researches primarily philosophy but also, on the side, novels and poems and plays and movies — I am prepared to come out and admit that I do not know what the value of the humanities is. I do not know whether the study of the humanities promotes democracy or improves your moral character or enriches your leisure time or improves your critical thinking skills or increases your empathy.

[T]his bit of ignorance poses no obstacle to me in the classroom.… I once asked the best teacher I ever had why she no longer taught her favorite novel, and she said that she stopped teaching a book when she found she was no longer curious about it. The humanistic spirit is, fundamentally, an inquisitive one.

In contrast, defenses of the humanities are not — and cannot be — conducted in an inquisitive spirit, because a defensive spirit is inimical to an inquisitive one. …

A defensive mind-set also encourages politicization. If the study of literature or philosophy helps to fight sexism and racism or to promote democracy and free speech — and everyone agrees that sexism and racism are bad and democracy and free speech are good — then you have your answer as to why we shouldn’t cut funding for the study of literature or philosophy. Politicization is a way of arming the humanities for its political battles, but it comes at an intellectual cost. Why are sexism and racism so bad? Why is democracy so good? Politicization silences these and other questions, whereas the function of the humanities is to raise them. …

The difference between the humanists and the scientists is simply that scientists are under a lot less pressure to explain why they exist, because the society at large believes itself to already have the answer to that question. If physics were constantly out to justify itself, it would become politicized, too, and physicists would also start spouting pious platitudes about how physics enriches your life. …

The task of humanists is to invite, to welcome, to entice, to excite, to engage. And when we let ourselves be ourselves, when we allow the humanistic spirit that animates us to flow out not only into our classrooms but also in our public-self presentation, we find we don’t need to defend or prove anything: We are irresistible.

Are the humanities valuable? What is their value? These are good questions, they are worth asking, and if humanists don’t ask them, no one will. But remember: No one can genuinely ask a question to which she thinks she already has the answer.

Cyberwarfare

Riffing on the shocking collapse of the Key bridge — though not suggest it was anything more than a stuff up, Noah Smith nevertheless riffs on cyberwarfare:

U.S. infrastructure is more vulnerable than many people realize. Recently, security services have been sounding the alarm about Chinese hackers targeting U.S. critical infrastructure:

Christopher Wray on Sunday said Beijing’s efforts to covertly plant offensive malware inside U.S. critical infrastructure networks is now at “a scale greater than we’d seen before,” an issue he has deemed a defining national security threat.

Citing Volt Typhoon, the name given to the Chinese hacking network that was revealed last year to be lying dormant inside U.S. critical infrastructure, Wray said Beijing-backed actors were pre-positioning malware that could be triggered at any moment to disrupt U.S. critical infrastructure.

“It’s the tip of the iceberg…it’s one of many such efforts by the Chinese,” he said[.]

That’s legitimately terrifying. Everything in the U.S. is networked these days, and almost everything uses Chinese-made electronic components of some sort. China also makes most of the world’s ships. It’s easy to imagine dozens or even hundreds of disasters like the Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse happening on the day that China attacks Taiwan. So we should harden both our cyber infrastructure and our physical infrastructure as best we can, in preparation for that day.

I don’t want the US to relax about cyberwarfare. The Chinese may well be doing what they’re described as doing. It’s also possible that they’d pull the trigger the day they invade Taiwan — if they do. But it would be incredibly stupid of them. I expect it’s much more likely that that stuff just stays in the background. I think the US would be nuts to defend Taiwan myself, and we’d be even more nuts to join them — and I’m a defender of strong action in Ukraine. But let’s even assume a shooting war over Taiwan. It would be localised around Taiwan. It would be hard to imagine a sane US (yes, I know we’re making assumptions here) attacking the Chinese mainland. Likewise China bringing about a hundred or so disasters on US soil seems to be about as escalatory thing you could do.

Happiness is in the remembering, not in the doing

From psychologist Daniel Kahneman who died this week aged 90. He won the Nobel Prize from economists for opening up a line of research into what people actually did rather than what simple mathematical models of optimal decision maker did. The discipline was grateful for a module it could bolt onto its worldview that didn’t disrupt the discipline’s intellectual habits too extensively. The full interview is here.

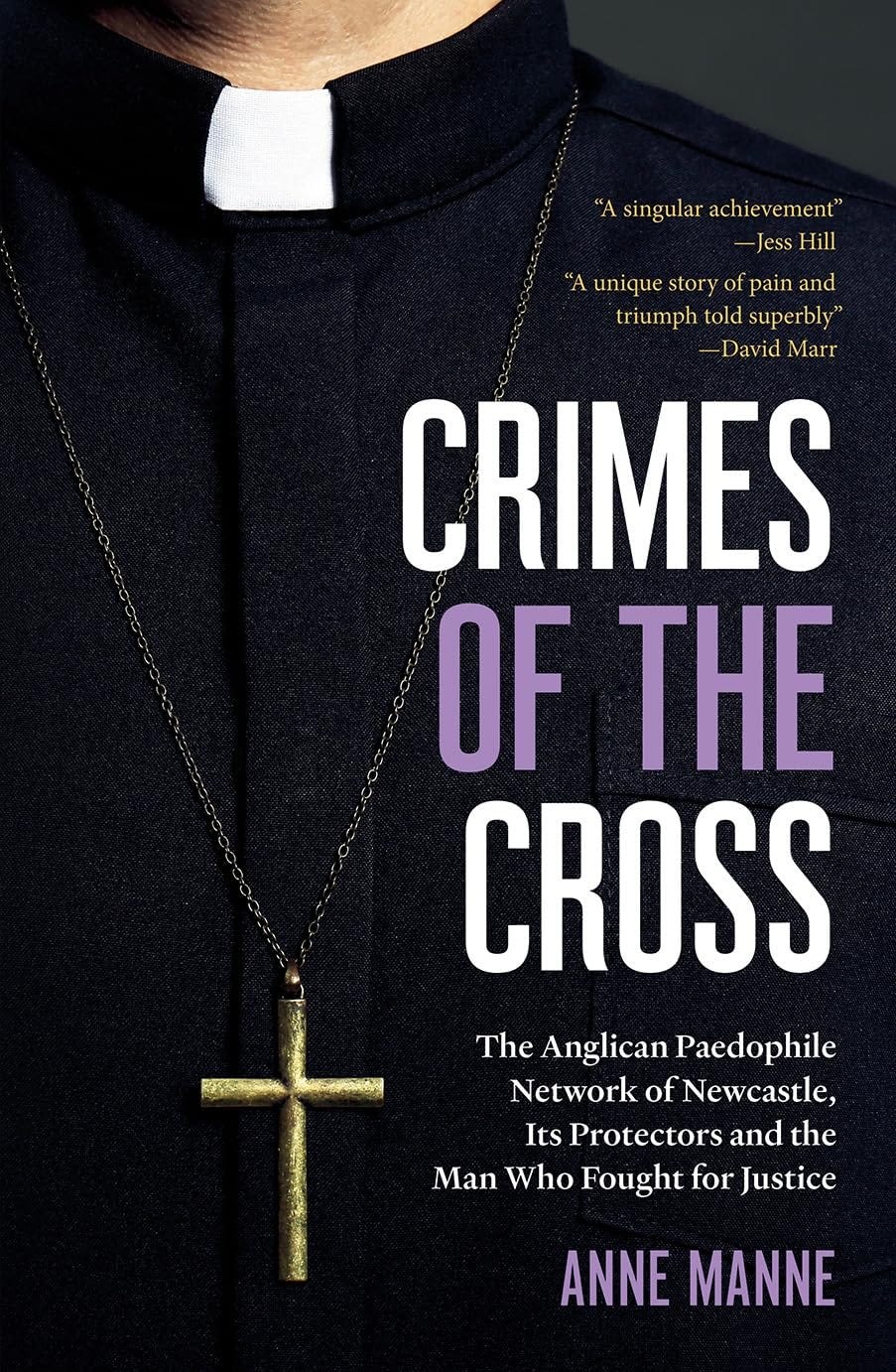

From a review of the above book:

Case Study 42 of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse is not seared into Australian consciousness in the way that it should be. … Anne Manne’s powerful Crimes of the Cross: The Anglican Paedophile Network of Newcastle, Its Protectors and the Man Who Fought for Justice seeks to correct this historical oversight. …

Our entry point and guide throughout Manne’s book is Steve Smith, a Newcastle man sexually abused by Anglican priest George Parker in the 1970s. … Manne’s portrayal of Smith is warm and admiring but does not flinch from the damage that abuse can inflict on survivors. … In adulthood, Smith’s drive to hold the diocese to account lands him in the sights of what Manne calls the “grey network”: the protection racket of complicit lawyers, officials and laity who enabled the “dark network” of paedophile priests. …

Chapter upon chapter builds a picture of the magnitude of clergy abuse and religious hypocrisy. … While the book was hard to put down, I often found myself blinking in disbelief, staring at the wall, trying to process the latest revelation before I went on to the next. The book presents a carousel of compromised leaders, paedophile priests, manipulative church mandarins, hostile judges, incurious journalists and groomed laity. Church insiders subverted legal processes, falsified records, attacked whistleblowers and insidiously gaslit survivors. …

The last half of the book documents the clash between a committed band of survivor advocates and honest church representatives on the one hand and a malignant tradition of normalised paedophilia on the other. Accounts of death threats, physical assaults, slashed tyres and sabotaged car brakes unfold. …

One of the accomplishments of the book is that, despite the depravity Manne documents, she has delivered a hopeful story of courage and triumph. The figure of Smith provides a grounding and buoyant presence as his bravery and persistence garners him allies, momentum and, ultimately, vindication. Over the course of the book, Manne maps out the blueprint whereby a group of survivors, supporters and honest operators overcame the “dark network” that had infiltrated the diocese. She celebrates a long but successful struggle for justice that should become a part of national historical awareness.

Filed under “I should have read but haven't yet”

Or “I haven’t read it but you absolutely must!”

A new adaptation to the second (Substack) age of blogging.

On not understanding how ‘power’ can reside in ‘ideas’

Henry Farrell takes issue with two economists. Brad Delong and Noah Smith in their discussion of two other economists’ book on Acemoglu and Johnson’s economic and political history of technology, Power and Progress. I think Brad and Noah are economists of arresting terrificness. But I agree with the points made in Henry’s post, though I think he might have stopped after the following summary of the two views of power thus. (If you find the summary of Noah’s theory a bit too abbreviated read the essay. I found it hard to extract a paragraph or two explaining it clearly.)

To sumarize: Noah’s Theory of Acemoglu and Johnson is as follows.

Techbros and entrepreneurs write blogposts and tweets in a free and thriving marketplace of ideas. Through luck and eloquence, the techbros persuade people that their arguments are right. This Is Somehow Power.

Acemoglu and Johnson’s Theory of Acemoglu and Johnson is just a little bit different.

Success in ideas is in part stochastic. Luck does play a role. But so do systematic inequalities.

People who are perceived as more successful have higher social status and are more likely to have influence.

People who do not belong to disempowered minorities have higher social status and are more likely to have influence.

People who have dense connections to powerful economic networks are more likely to have influence.

People who have the ears of politicians are more likely to have influence.

People whose voice is amplified by existing institutions and organizations are more likely to have influence.

People who have substantial financial resources to sway journalists and experts are more likely to have influence.

This ain’t no level playing field market of ideas! Political, financial and social asymmetries have substantial consequences for who has influence and who has not.

Judith Butler: the hatchet job

I haven’t read much Judith Butler and am not likely to. But I have read enough to be highly suspicious. So here’s a few paragraphs from a hatchet job in The Atlantic that you may find of interest.

Judith butler, for many years a professor of rhetoric and comparative literature at UC Berkeley, might be among the most influential intellectuals alive today. Even if you have never heard of them (Butler identifies as nonbinary …), you are living in their world, in which babies are “assigned” male or female at birth, and performativity is, at least on campus, an ordinary English word. Butler’s breakout 1990 book, Gender Trouble, argued that biological sex, like gender, is socially constructed, with its physical manifestations mattering only to the degree society assigns them meaning. The book is required reading in just about every women’s-, gender-, or sexuality-studies department. Butler has won a raft of international honors and been burned in effigy as a witch in Brazil. How many thinkers can say as much? …

In 1998, they won first prize in the annual Bad Writing Contest run by Philosophy and Literature, an academic journal. The next year, the philosopher Martha Nussbaum published a coruscating takedown, “The Professor of Parody,” in The New Republic, in which she argued that Butler had licensed a whole generation of feminist academics to blather incomprehensibly about semantics while ignoring the real-life global oppression of women. In the 1999 preface to a new edition of Gender Trouble, Butler struck back by attacking “parochial standards of transparency” and comparing critics to Richard Nixon, who would notoriously begin statements full of lies and self-excuses with the phrase “Let me make one thing perfectly clear.” Maybe the criticism stuck with Butler, though. … Butler also began publishing in The Guardian, The Nation, and other venues. Who’s Afraid of Gender?, Butler’s first book for a nonacademic readership, is not particularly well written, and it’s quite repetitious (a whole paragraph is repeated, along with many, many phrases and ideas). But it’s not difficult. In fact, it’s all too simple.

The central idea of Who’s Afraid of Gender? is that fascism is gaining strength around the world, and that its weapon is what Butler calls the “phantasm of gender,” which they describe as a confused and irrational bundle of fears that displaces real dangers onto imaginary ones. Instead of facing up to the problems of, for example, war, declining living standards, environmental damage, and climate change, right-wing leaders whip up hysteria about threats to patriarchy, traditional families, and heterosexuality. And it works, Butler argues: “Circulating the phantasm of ‘gender’ is also one way for existing powers—states, churches, political movements—to frighten people to come back into their ranks, to accept censorship, and to externalize their fear and hatred onto vulnerable communities.” Viktor Orbán, Giorgia Meloni, Vladimir Putin, even Pope Francis—all inveigh against “gender.” …

But is the gender phantasm as crucial to the global far right as Butler claims? Butler has little to say about the appeal of nationalism and community, insistence on ethnic purity, opposition to immigration, anxiety over economic and social stresses, fear of middle-class-status loss, hatred of “elites.”

Intriguing tidbit from the 1950s

From NS Lyons

A nice little self-aware 1952 poem composed by Ford Foundation staffers out of the text of their annual report, which I found digging through their history:

Take a dozen Quakers—be sure they're sweet and pink

Add one discussion program to make the people think;

Brown a liberal education in television grease

And roll in economics, seasoned well with peace.

Crush a juvenile delinquent (or any wayward kid)

And blend it with the roots of an Asiatic's id.

Dice teachers' education, and in a separate pan

Make a sauce of brown technicians from India-Pakistan

And pour it over seed corn in a pilot demonstration,

One that has been flavored with peel-off implication.

Take a board of good conservatives, the nicest you can buy,

And mix them with the white of a beaten liberal's eye;

Now render the conditions of a peace that's just and free

And mix them with insistence on national sovereignty.

Stir everything together, and when the fire's hot,

Pour a little Russian exile into the steaming pot.

Sweeten with publicity all the serving bowls

(By the way, this recipe serves two billion souls),

Garnish with compassion—just a touch will do—

And serve in deep humility your philanthropic stew.I have a firecracker of a piece on the Ford Foundation upcoming in the next issue of City-Journal magazine (as well as here once it is online).

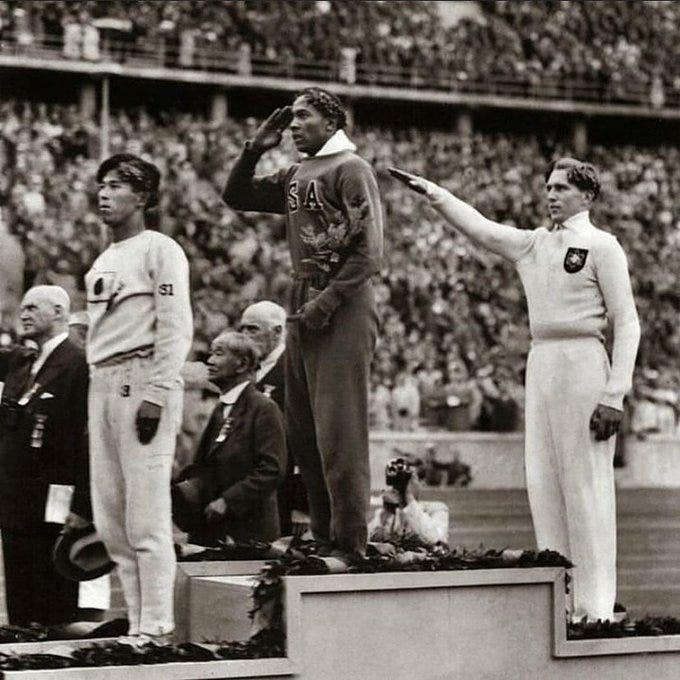

From Lutz Long to Jesse Owens

From this tweet:

After the Olympics, the two kept in touch via mail. Below is Long's last letter to Owens while he was stationed with the German Army in North Africa during World War 2. Long was later killed in action during the allied invasion of Sicily in 1943.

"I am here, Jesse, where it seems there is only the dry sand and the wet blood. I do not fear so much for myself, my friend Jesse, I fear for my woman who is home, and my young son Karl, who has never really known his father.

My heart tells me, if I be honest with you, that this is the last letter I shall ever write. If it is so, I ask you something. It is a something so very important to me.

It is you go to Germany when this war done, someday find my Karl, and tell him about his father. Tell him, Jesse, what times were like when we not separated by war. I am saying—tell him how things can be between men on this earth.

If you do this something for me, this thing that I need the most to know will be done, I do something for you, now. I tell you something I know you want to hear. And it is true.

That hour in Berlin when I first spoke to you, when you had your knee upon the ground, I knew that you were in prayer. Then I not know how I know. Now I do.

I know it is never by chance that we come together. I come to you that hour in 1936 for purpose more than der Berliner Olympiade. And you, I believe, will read this letter, while it should not be possible to reach you ever, for purpose more even than our friendship.

I believe this shall come about because I think now that God will make it come about. This is what I have to tell you, Jesse. I think I might believe in God. And I pray to him that, even while it should not be possible for this to reach you ever, these words I write will still be read by you. Your brother, Luz"

And from a follow-up tweet:

Heaviosity half-hour

Aurelian Craiutu’s “In Search of an Elusive Virtue”

Much thanks to Chrisos for putting me onto this scholar for our times, an historian and philosopher of the virtue (political and intellectual) of moderation. He also has a very cool first name — Aurelian. His last name is just there to make sure we’re paying attention — Craiutu. He’s been beavering away on this agenda for much of his intellectual career it seeems and now he finds that cometh the hour, cometh the man. Perhaps he is that man. I’ve had a few goes at similar ideas. Most recently I invited you to join me in the alt-centre.

Nearly twenty years ago [Yikes — ed] I described myself as a conservative, liberal social democrat. Mark Bahnisch then commented that the ‘problem’ with centrism is it’s hard to be ‘passionate’ about it. He then turned it into a short post on which right-leaning moderate Andrew Norton commented:

But do you need to be passionate about your politics? Or is the use of politics as part of personal therapy so pervasive that assumptions of therapy (the need to feel strong, positive emotion) are spilling over into politics? Persistence and perspective are I think more valuable attributes to bring to politics, and far more likely to be found in centrist parties.

Be that as it may here’s the link from the last newsletter to Craiutu’s interview with Andrew Sullivan. It’s excellent.

Here’s Aurelian (did I mention he had a cool name?)

Prologue

In Search of an Elusive Virtue

People offer advice, but they do not give at the same time the wisdom to benefit from it.

—La Rochefoucauld

Many may still remember Barry Goldwater’s famous words on the occasion of his nomination acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention in San Francisco in 1964: “I would remind you that extremism in the pursuit of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” After pronouncing these memorable words, Goldwater gracefully accepted the nomination of his party and went on to score a massive defeat at the polls. His extreme defense of liberty was seen by many in tension with his opposition to the Civil Rights Act, and this contradiction (in addition to other things, of course) was enough to send Goldwater to the ranks of political losers.

Nonetheless, it would be difficult not to have some sympathy for his immoderate position in defense of liberty at a critical moment during the Cold War when the fate of freedom in the world was uncertain, to say the least. We would be mistaken to characterize it, to use Senator William Fulbright’s own words, as “the closest thing in American politics to an equivalent of Russian Stalinism.” Goldwater was none of that, to be sure; he was an American patriot who believed in his country’s mission to spread liberty in an embattled world during the Cold War. I have no intention of reassessing Goldwater’s legacy here. I begin with his critique of moderation because in my view, it misrepresented in an unforgettable way a cardinal virtue without which our political system would not be able to function properly. This understudied and underappreciated virtue deserves a closer look to reveal its nature, complexity, and potential benefits.

This is precisely what I hope to achieve in the present book, which is part of a larger multivolume research agenda whose main goal is to bring to light the richness of political moderation in the history of modern political thought. The concept of moderation was already present, as it were, between the lines in my first book, Liberalism Under Siege: The Political Thought of the French Doctrinaires (2003). It came to the fore in a subsequent volume, Elogiul moderaţiei (In Praise of Moderation), written for a general public and published in Romanian in 2006. Six years later, in A Virtue for Courageous Minds: Moderation in French Political Thought, 1748–1830, I began exploring in detail the tradition of political moderation in France (a second volume covering the period 1830–1900 in France will follow in due course). I argued that political moderation constitutes a coherent, complex, and diverse tradition of thought, an entire submerged archipelago that has yet to be (re)discovered and properly explored. This “archipelago” consists of various “islands” represented by a wide array of ideas and modes of argument and action; at the same time, it also includes elements and political strategies that were not shared by all moderates, or were shared only to varying degrees. The book ended (rhetorically) with a “Decalogue of Moderation” that emphasized the complexity, difficulty, and richness of this virtue. I argued that, far from being of mere historical interest, moderation may be particularly relevant in a post–Cold War age such as ours because it enables us to deal with the antinomies and tensions at the heart of our contemporary societies and allows us to defend the pluralism of ideas, principles, and interests against its enemies. I also insisted that moderation should be regarded as an eclectic virtue transcending the conventional categories of our political vocabulary. While moderation may sometimes imply a conservative stance embraced by those who seek to preserve the status quo, it would be inaccurate to claim that all calls for moderation are little else than conservative or “reactionary” attempts to maintain unjust social and political privileges or components of an ideological system by which modern elites seek to legitimize their power and domination.

The present volume has a different emphasis and examines select faces of political moderation in the twentieth century. It pays special attention to its shifting polemical and rhetorical uses in different political and national contexts and addresses the following questions: What did it mean to be a moderate voice in the political and public life of the past century? How did moderate minds operate compared to more radical spirits in the age of extremes? What were they seeking in politics, and how did they view political life? We will also take up a few more general questions: What are the characteristics of the “moderate mind”1 in action? To what extent is moderation contingent upon the existence and flourishing of various forms of political radicalism? What do moderates have that others lack? Is moderation primarily a style of argument that varies according to context, circumstances, and personal character? Or does it also have a strong ethical-normative core? And, finally, are there any common elements of what might be called the “moderate” style?2

This volume does not aim to be—nor should be seen as—a work of political contestation; it is first and foremost a work in modern intellectual history, history of ideas, and political theory that contributes to contemporary debates on political virtues, radicalism, and extremism. Without treating moderation as a unitary block, I show its heterogeneity and diversity by focusing on the writings of representative authors (mostly European, with a few American exceptions) who defended their beliefs in liberty, civility, and moderation in an age when many intellectuals shunned moderation and embraced various forms of radicalism and extremism. Although their political and intellectual trajectories were significantly different, these thinkers may be seen as belonging to a loosely defined “school” of moderation that transcends strict geographical and temporal borders. I insist at the outset that there is no “ideology” (or party) of moderation in the proper sense of the word and that moderation cannot be studied in the abstract, but only as instantiated in specific historical and political contexts and discourses. What is moderate in one context and period may significantly differ from what is moderate at another point in time, which is another way of saying that moderation is not a virtue for all seasons and for everyone.

In treating such a complex subject as moderation, it is necessary to be as ecumenical as possible and examine a wide cast of characters including thinkers from all aisles of the political spectrum and from both sides of Europe (West and East). The last detail is particularly relevant today when the memory of the Cold War seems to be revived by recent political developments in Russia and the Middle East. Since the main focus of the book is on European political thought, the least represented here is the American political tradition. Nevertheless, the brief discussion of Judith Shklar’s “liberalism of fear”3 and Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s “vital center”4 and the occasional references to Edward Shils’s writings on civility and Albert O. Hirschman’s views on self-subversion should make it plain that American scholars, many of whom were of European extraction, brought important contributions to the debates on moderation and extremism in the twentieth century.

We will explore both well-known authors (such as Isaiah Berlin, Raymond Aron, and Michael Oakeshott) and lesser-known ones (such as Norberto Bobbio, Leszek Kołakowski, and Adam Michnik) whose selected writings had something important to say about political moderation in an age of extremes. Taken together, these thinkers do not offer a comprehensive account of this virtue, and the reader might wonder, for example, whether other major figures such as Hannah Arendt, Albert Camus, or John Maynard Keynes should not have been examined as well.5 Needless to say, there is no shortage of worthy candidates. One thing is certain though: we need an open and ecumenical form of intellectual history, one that takes into account the creativity of both well-known and allegedly marginal authors whose works can illuminate the complexity and richness of the tradition of political moderation in the twentieth century.

The thinkers discussed or mentioned in these pages came from several national cultures (mainly France, Italy, England, Poland, and the United States) and belonged to different disciplines (political theory, philosophy, sociology, literature, and history of ideas). Not all of them identified themselves primarily as moderates; some preferred to be seen as liberals or conservatives, while others rejected all labels. What makes them fascinating and noteworthy is precisely their syncretism as illustrated by their different trajectories and ideas as well as by the fact that many of these thinkers, brave soldiers in the battle for freedom, refused narrow political affiliation and displayed political courage in tough times. Some of them started off their careers on the Left and then gradually embraced political moderation, moving toward the center or the center-right. A few of them exercised significant political influence as journalists—Aron, for example, wrote for Le Figaro and L’Express for over three decades, while Michnik has been the editor of the influential Gazeta Wiborcza for over two decades and a half now—or engaged intellectuals or politicians such as Bobbio who was a member of the Italian Senate. Still others such as Berlin and Shklar remained in the ivory tower of academia, even if they never lost interest in political issues.

Be that as it may, these thinkers paid a certain price for their political moderation because they refused to play the populist card or did not embrace trendy themes for short-term gains. As such, they lived at a slightly awkward tangent to their contemporaries with whom they had a complex relationship, punctuated by occasional crises and a few tense moments. Some of them were subjects of suspicion or even contempt, as demonstrated by the Parisian students in 1968 who thought it was “better to be wrong with Sartre than right with Aron.” Finally, the thinkers studied here kept open the dialogue with their opponents even in the most difficult times. This was the case with Aron and Sartre, Bobbio and the Italian Communists, and Michnik and the former Polish Communist leaders.

Although the chapters of this book can be read individually as a series of intellectual vignettes, they are not intended as comprehensive studies of any of the aforementioned authors. Instead, the main focus is on the concept of political moderation, and each chapter illuminates a certain face of this elusive virtue as reflected in their writings. I examine how these thinkers conceived of moderation and, where applicable, how they practiced it. To this effect, I focus on their most relevant writings and comment on their intellectual and political trajectories only when they seem relevant to the larger topic of moderation. The mentality of our authors will remain obscure if we do not take into account how they related their ideas to the events that defined their lives, such as communism, fascism, the Soviet Union, the postwar European reconstruction, and the student revolts of 1968. The moderates discussed in these pages differed among themselves in several respects and belonged to different intellectual and spiritual constellations. Yet, at the same time, they also shared many important things in common such as their belief in dialogue, their rejection of Manichaeism and ideological thinking, their embrace of trimming and political eclecticism, and their opposition to extremism and fanaticism in all their forms.

The first chapter discusses the ethos of moderation broadly defined. I begin by examining a few misrepresentations of moderation and then comment on the challenges associated with studying and writing about this elusive and difficult concept. Next, I emphasize the potential radicalism of moderation as a fighting virtue before turning to trimming as a key face of moderation and exploring its role in combating ideological intransigence and dogmatism. I challenge the common view of moderation as a conservative defense of the status quo and claim that this virtue can also have its own radical side depending on circumstances. Finally, I focus on two essential aspects of moderation: as a synonym of civility and openness and as an antonym of fanaticism and dogmatism. As such, moderation appears as an essential ingredient in the functioning of all open societies because it acts as a buffer against extremism and promotes a civil form of politics indispensable to the smooth running of democratic institutions.

The second chapter examines the metaphor of the “committed observer”—le spectateur engagé—as a face of political moderation in the writings of Raymond Aron (1905–83). The choice of a French author for a book on moderation may seem surprising at first sight. Yet, a closer look at the French political tradition reveals that the latter has combined a well-known tendency to radicalism with a lesser-known but surprisingly diverse tradition of political moderation. Aron’s writings such as The Opium of the Intellectuals, An Essay on Freedom, Thinking Politically, and his Memoirs are discussed here as examples of lucid political judgment in an age of extremes when many intellectuals shunned moderation and embraced radical or even extremist positions. As an engaged spectator raised in the tradition of Cartesian rationalism, Aron reflected on a wide variety of topics such as the philosophy of history, war and peace, and the virtues and limitations of liberal democracy while commenting extensively on the major political events of his time. His works shed fresh light on the relationship between moderation, engagement, responsibility, and political judgment. Among other topics discussed in this chapter are the role of intellectuals in politics, Aron’s reading of Marxism, his analysis of the revolution of 1968 in France, and his intellectual dialogue with Hayek. I also illustrate Aron’s political moderation by analyzing his critical attitude toward General de Gaulle and his uncompromising attitude during the Algerian crisis when Aron defended the independence of the former colony.

Chapter 3 focuses on the relationship between political moderation, freedom, monism, and pluralism in the writings of Isaiah Berlin (1909–97) examined in the larger context of the Cold War liberalism. Berlin is an obvious choice for a book on moderation given his endorsement of pluralism and vigorous critique of political idealism, utopianism, and monism. I explore these topics along with Berlin’s anticommunism and opposition to determinism by focusing on some of his best known essays (such as “Two Concepts of Liberty,” “The Pursuit of the Ideal,” and “The Originality of Machiavelli”), his interpretations of Russian thinkers, as well as his extensive correspondence. In this chapter, I also link Berlin’s works to those of other Cold War liberals such as Arthur Schlesinger Jr. (1917–2007) and Judith Shklar (1928–92) whose respective theories of the “vital center” and “liberalism of fear” he partly shared. Another common trait linking these authors was their views on the role of passions, vices, and reason in politics. They dreaded the presence of irrationality, cruelty, wickedness, and evil in history and attempted to understand their roots and mitigate their influence in reality. Finally, I explore Berlin’s moderate temperament by comparing it with that of two of his favorite authors, Alexander Herzen and Ivan Turgenev.

In Chapter 4, I turn to the writings of the Norberto Bobbio (1909–2004), the most prominent twentieth-century Italian political philosopher, in order to examine how constitutional liberalism and socialist democracy came to be reconciled in Italy and gave rise to an original yet still little-known form of “liberalsocialism,” an important chapter in the history of political moderation in the twentieth century in which Bobbio and some of his friends (such as Guido Calogero) played an important role. The experience of fascism, the ideological divisions of the Cold War, and the slow and protracted democratization of Italian society during the 1960s and 1970s exercised decisive influence on Bobbio, who emerged as a strong advocate of constitutionalism, equality, and the rule of law. I examine his complex dialogue with the Italian communists and Marxists as well as the philosophy undergirding his politics of culture elaborated in Politica e cultura (1955) and other texts written during the Cold War; next, I consider Bobbio’s views on political engagement and the role of intellectuals in society. Later in life, he argued that the most important virtue of intellectuals is mitezza (meekness), an important and intriguing face of political moderation. I argue that Bobbio’s meekness derived from a particular forma mentis that could also be found at the heart of his philosophy of dialogue and politics of culture.

Chapter 5 focuses on the relationship between moderation, trimming, the politics of faith, and the politics of skepticism in the writings of the British political philosopher Michael Oakeshott (1901–90), best known for his critique of rationalism in politics and his theory of civil association sketched in On Human Conduct (1975). An attentive rereading of Oakeshott’s writings shows that his target was not only rationalist socialism, but also those forms of conservatism that tend to evolve into rigid ideologies, thus losing sight of the complex nature of society and politics. After examining Oakeshott’s distinction between “civil” and “enterprise” associations and his critique of political rationalism and ideological thinking, I focus on the affinities between moderation and conservatism in Rationalism in Politics (1961). Next, I turn to Oakeshott’s posthumously published The Politics of Faith and the Politics of Skepticism (1996) in which he distinguished between two fundamental types of politics that, he argued, should be seen as the two poles between which modern politics have moved for the past few centuries. I draw on Oakeshott’s reworking of the ideas of a classical seventeenth-century text, Halifax’s “The Character of a Trimmer,” and comment on his claim that we need a mixture between the politics of skepticism and of faith to navigate the troubled waters of modern politics.

The last (sixth) chapter turns to Eastern Europe and focuses on two concepts related to political moderation that were central to the anticommunist resistance in Poland: “new evolutionism” and “self-limiting revolution.” The first became a key principle in the agenda of the Workers’ Defense Committee (also known as KOR, founded in 1976), while the second defined the platform of the Solidarity movement beginning with the summer of 1980. The concept of “new evolutionism” was theorized by Adam Michnik, who developed it in the 1970s in a series of important essays collected later in his Letters from Prison (1987). In the footsteps of Leszek Kołakowski (1927–2009), Michnik presented a persuasive case for a reformist agenda while supporting the general goal of a limited gradual revolution. In so doing, he also argued for a creative form of “radical moderation” at a key time when all of Europe was struggling to end the Cold War. I pay special attention to Michnik’s ethics of dialogue and political trimming as illustrated, among others, by his position on the dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Left in Poland as well as his conversations with Václav Havel and General Wojciech Jaruzelski collected in Letters from Freedom (1998). I also examine Michnik’s controversial views on lustration and decommunization before concluding with a few reflections on the relationship between moderation and “inconsistency” in politics.

In the epilogue, I elaborate on the broad themes (metanarratives) of the book and highlight their contemporary implications for us today. I revisit the main arguments for moderation made in the previous chapters and reflect on how the hybridity of this virtue mirrors our world’s ideological and institutional complexity. I argue that moderation should not be expected to always bring forth moral clarity and explain why there can be no ideology of moderation. As such, the latter must not be equated with tepidness or (always) seeking the midpoint between two opposing poles and opportunistically planting oneself there. In some cases, moderation is, in fact, the outcome of a long, arduous, and open-ended process of political learning, as the chapters of the present book demonstrate.

“A history book—assuming its facts are correct—stands or falls by the conviction with which it tells its story,” Tony Judt once said (Judt and Snyder, 2012: 260). “If it rings true, to an intelligent, informed reader, then it is a good history book.” I venture to say the same about a book in political theory or intellectual history, and especially about a volume on political moderation. The proper attitude for anyone writing on this difficult virtue is patience, and that is why I am inspired by the following words of Ortega y Gasset: “I am in no hurry to be proved right. The right is not a train that leaves at a certain hour. Only the sick man and the ambitious man are in a hurry.”6 These days, it is quite common to be pessimistic or cynical about the chances of moderation in the short term. It is equally normal to lament its political powerlessness in a world dominated by ideological intransigence in which in order to be successful and make headlines, it seems that one must often espouse mostly extremist and immoderate positions. Anyone writing about moderation seems therefore to face daunting challenges.

To tell a convincing story about the types of moderation espoused by the authors studied in this book requires that we clearly highlight the common themes shared by their political and intellectual agendas as well as the differences among them. My ambition is to rethink an old concept and through it, to identify a certain school of thought where few had perceived its existence before. This raises a few significant methodological questions and challenges. First, there is the danger of converting some scattered or incidental remarks into a coherent doctrine of moderation which has never existed in reality. A related risk might be the tendency to underplay the differences between the ideas, agendas, and temperaments of the moderates studied here and overplay, in turn, the affinities or similarities among them. Yet another problem might arise from the attempt to offer a series of individual portraits and intellectual vignettes that might have only tenuous links among them.

My hope is that the approach used in this book successfully avoids all of these problems. I admit from the outset that moderation is a particularly difficult concept placed at the heart of a complex moral and political field. When reflecting upon the nature of this virtue, rather than relying upon the instruments of analytical philosophy, we need to adopt a concrete way of thinking about politics that takes into account the complex interaction among ideas, passions, institutions, and events. What makes moderation a notoriously difficult subject is not only the virtual impossibility of offering a coherent theory of this virtue, but also the fact that moderates have worn many “masks” over time that are different and may sometimes be difficult to relate to each other: prudence, trimming, skepticism, pluralism, eclecticism, antonym of zealotry, fanaticism, enthusiasm, and the “committed observer.” Equally important is that claims for moderation have been part of historical controversies and debates and thus carry with them a certain rhetoric and a plethora of connotations, some more obvious than others.7 Among the concrete examples of agendas that claimed to be moderate one could mention the following: the juste milieu between revolution and reaction in postrevolutionary France, Ordoliberalism in postwar Germany, and social democracy in Sweden as a middle ground between pure free market capitalism and full state socialism. There were also several political movements that claimed to follow the principles of moderation: the Solidarity movement and the “self-limiting” revolution in Poland, Charter 77 in the former Czechoslovakia, and the doctrine of the “Third Way” in the United Kingdom in the 1990s.

Hence, the selection of the authors has been carefully thought out and the themes in each chapter have been chosen with the general goal of presenting a few faces of moderation that remain relevant to twenty-first-century readers. There are important differences among our authors that should not be glossed over. If they were all political moderates in one way or another, they had different temperaments and followed distinctive agendas dictated by the peculiar contexts in which they lived. While there may not be perfect ideological balance among them, I have included thinkers from different aisles of the political spectrum (Bobbio on the Left, Oakeshott on the Right, Berlin and Aron in the middle) as well as a few such as Adam Michnik or Leszek Kołakowski who are quite difficult to classify according to our conventional political categories.8

Since projects similar to this one may appear to contain an air of intellectual superiority, chimerical fancy, and even conceit, I acknowledge from the outset with Shaftesbury that “the Temper of the Pedagogue suites not with the Age. And the World, however it may be taught, will not be tutor’d” (2001: 1:44). Hence, my main goal is to continue a conversation about an important but still surprisingly neglected virtue that is worth having today in our heated political environment. Overall, in the following pages I offer a spirited tour of perplexities, not a doctrinal book or a political agenda. I therefore play the role of a tour guide who introduces the topic and reflects on the virtues and limits of political moderation through the voices of a few thinkers who wrote about it or practiced it.

I do not hope to convince everyone about the benefits of moderation, nor do I want to give the impression that I might be an unconditional defender of this difficult virtue. It would be ironical (and absurd) to write a book about the latter that attempts to definitively settle the debate. One of the main ideas of this volume is that moderation has not one but many faces tied to various shifting contexts. It is important to remember that what was moderate in the 1920s or 1960s may no longer be so today, at least not in the same manner. This does not mean, however, that we should embrace nihilism or relativism for lack of a better solution. As the moderates discussed here show, some choices are (were) more reasonable than others and ought to be pursued (with the proper discernment) in spite of their imperfection.

One of the tasks of political philosophers is to challenge and help enlarge the sense and range of possibilities. I prefer to let those who open this book find and follow their own path, allowing them to see their own sights and draw their own conclusions as they think fit. If I have a sense of the final destination, I am much less certain about the best ways of finding the elusive archipelago of moderation. The readers are therefore invited—and encouraged—to be active participants on this journey, which might, after all, turn out to be much more important and fascinating than Ithaca itself—in this case, the concept of political moderation. Without the appeal of the latter, however, we might have never started the voyage and set sail for the unknown.