How adversarialism holds back abundance

And other things you should check out

Join me for lunch with a founder of Australia’s blogosphere

Back in the early days of blogging there were quite a few get togethers. This Monday - i.e. in two days, we’re hosting Ken Parish one of the fathers of the blogosphere who began blogging at The Parish Pump and then founded the group blog TroppoArmadillo from his hideaway in Darwin. It was quite the group blog with eight to ten pretty regular posters. ClubTroppo, which is still with us, was a bit of a rebadging in around 2005. Ken has been going through a lot as he’s nursed his wife Jen who in now in a hospice. But the lunch will be an opportunity to catch up and say ‘thanks’ to Ken for his generosity including, but not limited to, donations to the public commons and his attempts to help us stay sane as the world has gradually gone mad.

The lunch is at 12.30pm at Sorsi and Morsi in St Kilda, and if you’d like to come, please drop me a line on ngruen AT gmail and I’ll let Ken know. It would be good to see you there and I don’t think you need to be an old timer or even teetering on the edge of death by old age like me, Ken and a few others who may be wheeled in.

Extract from a fine piece

Hunter S. Thompson = Ernest Hemingway. And not in a good way!

A wider framing of the ‘abundance agenda’

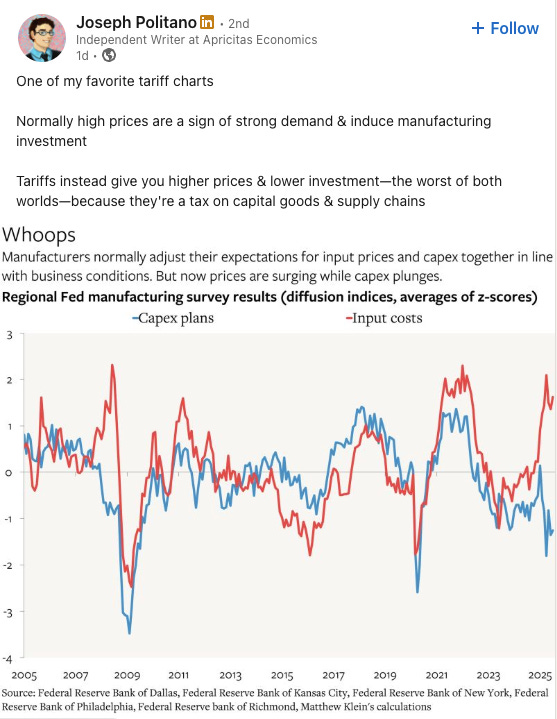

In 2023 Ezra Klein coined the term “everything‑bagel liberalism” to describe a tendency in progressive policymaking to pile on well‑meaning, but competing, objectives into projects—thus compromising the original goal.

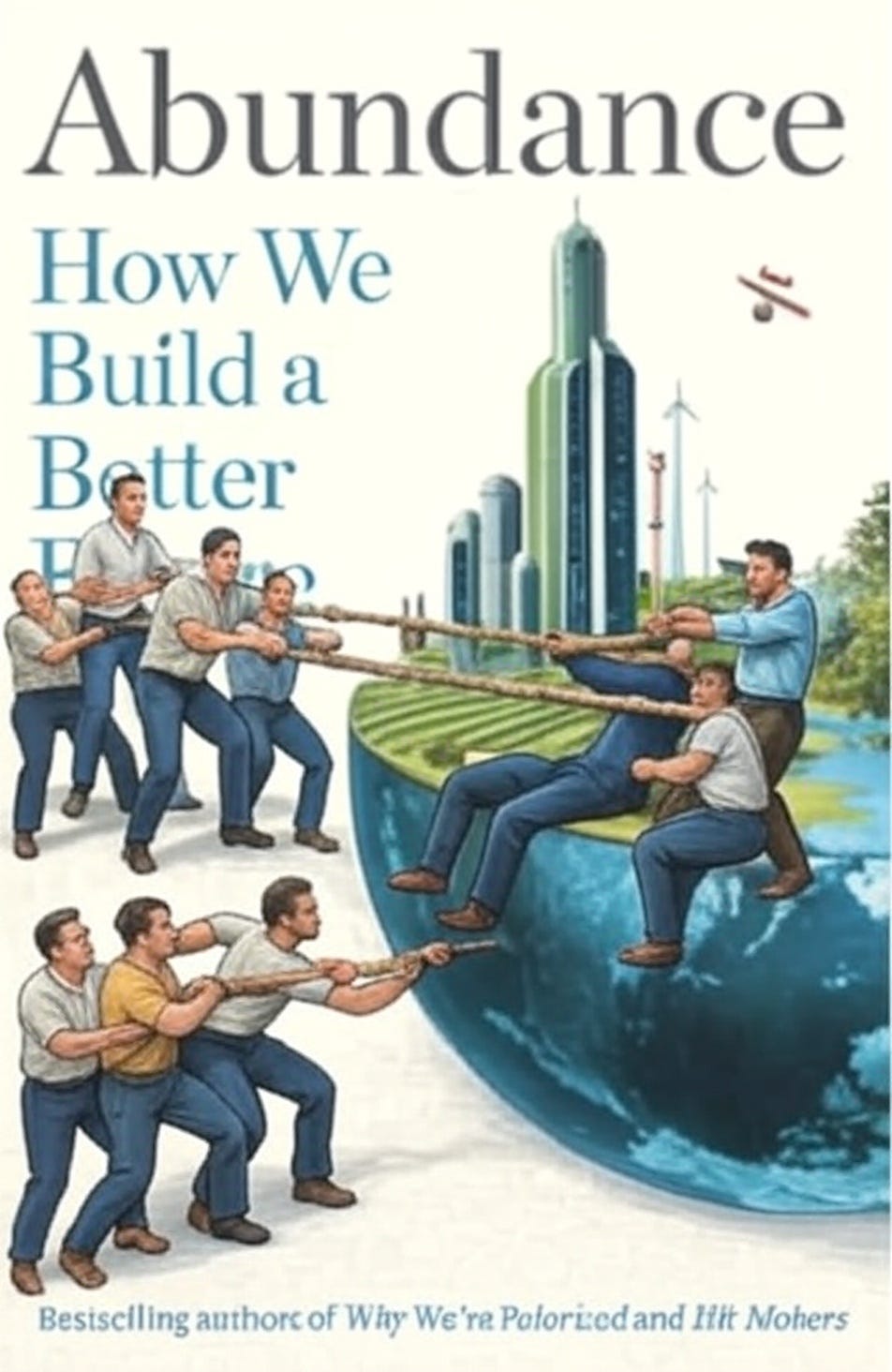

However, as we all know, ideas can be safely ignored until they turn up in a book. Klein fixed that with his co-authorship of Abundance which is now all the rage. Another thing that gives Klein’s ideas cut-through is their ideological edge in critiquing the foibles of the liberal left.

There’s certainly something to this framing, but I think there’s something deeper at work. In fact, come to think about it, I wrote an essay about it. A brief, not entirely satisfactory summary of some of its central arguments is below. (It began as a ChatGPT summary but got fairly heavily worked over. It’s not a great summary, but it’s not too bad and if you want to read the original, it’s here).

Trust and the Competition Delusion

This essay argues that we've fallen for a "competition delusion" - the mistaken belief that placing competitors in adversarial contest somehow produces the right outcome, without further attention to ensuring that the rules of the competition and the way they’re applied actually do secure the right outcome.

The Core Problem: Adversarial Structure vs. Truth-Seeking

Adversarial legal procedure presumes that the truth will out if we place an independent "umpire" between two competitors, each seeking a partisan outcome. In fact it produces a procedural obstacle course that is both inefficient and unfair compared with the European system in which, though parties lawyers are there to protect their clients’ legal rights, the independent judge’s need to get to the truth drives the process.

The problem is especially stark, and illustrative when it comes to expert opinion. "The more measured and impartial an expert is, the less likely he is to be used by either side." The result is a system in which the experts of both sides are seen as partisan and so a Gresham’s Law process sets in. Just as bad money drives out good, if your opponent introduces an expert biased to their own side, you will do the same on your own side. Meanwhile in European civil law systems, the judge’s need to get to the truth makes them the logical party to call experts.

The economic costs are stark: English-speaking countries impose around twice the liability costs on firms as European countries, with the most adversarial system - the US - imposing over 1.5% of GDP, four times the cost of the Netherlands. But inadequate attention to the centre isn’t just inefficient. It’s also unfair as better funded litigants use the system to predate on financially weaker litigants.

How This Plays Out Across Domains

Financial Services and Auditing

Just as our legal system lets parties choose their own experts, firms select their own auditors "all in the name of competition." This transforms what should be independent certification that a firms accounts represent reality into a lucrative game of finding ways to game the accounting standards. The ultimate result: the doubling of the cost of finance as a share of GDP while investment and productivity growth decline, and financialisation enables large firms and their wealthy owners to maximize profits while offloading risks to society.

Academic Research and Publishing

Universities adopted publication metrics to assess merit. Corporate publishers exploited academics' captive-market status, buying prestigious journals and multiplying subscription prices while academics provide all the labor. Career incentives tied to publication metrics created shortcuts to unreliable research, with only 11% of pre-clinical cancer studies proving replicable. The internet could have turbocharged collaborative science, but instead was "colonised largely for institutional and private benefit."

Media and Information

The "he-said-she-said" standard treats journalism like our adversarial courts - presenting both sides on a "level playing field" regardless of truth content. This keeps costs down but makes minimal demands on journalists to check facts or defend standards. Meanwhile resources devoted to "spinning" information for private advantage vastly outweigh those devoted to truthful reporting. Competition for ratings reduced presidential sound bites from 43 to 9 seconds between 1968 and 1988, prioritizing entertainment over illumination.

The Broader Pattern

Across all these domains, we've allowed private interests to set the rules of games that should serve the public interest. Instead of designing institutions that "bring out the best in humans," we've created systems where those with products to sell, axes to grind, and stories to spin determine the standards of competition. The result is systematic predation by insiders upon outsiders, economic inefficiency, and the degradation of the very expertise and trust that complex societies require to function.

Given my concerns in the , I’ve been gratified to see how others have documented these costs of reflexive adversarialism. I personally think the ethical problems are at least as important as the economic ones, but we all know money talks, so it’s nice to see the articles turning up. I’m not surprised that both are published by the Niskanen Centre which is one of the best think tanks around.

Abundance liberalism versus adversarial legalism

For decades liberals have embraced lawsuits, legal rights and judicial policymaking as means for creating social change and holding powerful interests to account, but in recent years second thoughts seem to be proliferating. Abundance liberals from Ezra Klein to Jen Pahlka have embraced Nicholas Bagley's argument in "The Procedure Fetish" (2019) that the accretion of rules backed by liberals to make executive branch policymaking more open, transparent and accountable has become a major barrier to progressive change.

Bagley's seminal article focused on the ways in which liberals' unexamined dedication to "proceduralism" has handicapped state capacity. His examples mainly come from his specialty, administrative law, where major new initiatives must run a gauntlet of procedural hurdles, many of them erected by liberals, before they can take effect...

This is a tradition of research that ranges far beyond administrative law to examine the myriad ways in which lawsuits have come to be a central aspect of American politics and public policy. The research raises questions about how the ambitions of abundance liberals can be realized without rethinking the role of litigation in American life and politics, and considering what could replace it...

A classic example of this long tradition of procedural skepticism is Robert A. Kagan's study of the long and contentious struggle over dredging the Oakland Harbor (1991, 2019), which illustrates why litigation can be so troublesome for a "liberalism that builds," and why reforming it can be so difficult. The Port of Oakland began in the 1970s to plan for dredging its harbor to keep it competitive with other ports that could accommodate larger, deeper ships. After Congress authorized the project in 1986, the Army Corps of Engineers completed an Environmental Impact Statement that included a plan to dump the dredged material in San Francisco Bay, but when concerns were raised, the Port proposed to move the material further out, to a location along the California coast...

Finally, in 1992, the Port was eventually allowed to go forward with a plan that included dumping some of the dredged material right where it had first proposed, in San Francisco Bay.

After nine years of litigation and delay, the project was completed in 1995. Kagan (2019:34) concludes:

Month after month, regulatory officials, scientists, and lawyers, arguing first in one legal forum, then in another, debated the propriety of decision-making procedures, the adequacy of sediment samples and tests for chemical contamination, and the reliability of environmental impact models. No proceeding produced any definitive finding that the proposed disposal plans were environmentally dangerous...

The root problem in the dredging fight, Kagan's study demonstrates, was a lack of legitimate governmental authority. In other nations, and perhaps at other times in American history, one could imagine such a conflict being resolved by an executive branch agency backed by elected officials, or through legislative bargaining among all the affected interests. In the dredging fight, though, there was no single political, bureaucratic, or expert body trusted and empowered to resolve the matter. "Adversarial legalism" is the term Kagan coined for the decentralized form of authority that instead prevailed...

Where other forms of governmental authority are typically centralized, public, and relatively stable, adversarial legal authority is decentralized, privatized, and fluid. These distinctive features make its effects double-sided. Adversarial legalism is theoretically open to all, including those disadvantaged in other facets of the political process, but that also makes it potentially costly both in time and money; decisions can drag on and on...

In his comparative research, Kagan contrasted American adversarial legalism with other forms of authority he argued often more effectively addressed social problems (Kagan & Axelrad 2000; Kagan 2019). Kagan's comparisons to Western European governments in environmental and labor policy illustrate why American public policy is so often shaped by adversarial legalism. In Western Europe, policymaking in these fields is often made through negotiations among "peak" associations; representatives of labor, business, and government come together to negotiate a solution that parliaments ratify...

The proceduralism that Bagley observed in administrative law, then, has even deeper and more extensive political roots than his article suggests. It should not be surprising that while lawsuits and litigiousness are regularly denounced in the media and popular culture (Haltom & McCann 2004; Barnes & Hevron 2018), and an array of studies have demonstrated the downsides of adversarial legalism, fundamental reform has proven difficult (Burke 2002; Barnes 2011; Burbank & Farhang 2017; Kagan 2019). The political power of adversarial legalism lies precisely in what it displaces: other, more centralized forms of authority, expert, bureaucratic and political, that Americans distrust. A "liberalism that builds" must grapple with what makes adversarial legalism so tenacious, its decentralization and participatory veneer. Abundance liberals must find other ways to generate authority that people can accept. This is the overriding political challenge for those who seek to reform the use of litigation in American public policy.

Dan Davies on the problem factory

I asked AI to summarise a long and impressively documented article by Dan Davies. It did a good job.

This article presents a detailed analysis of why infrastructure projects in common law countries (UK, US, Australia, Ireland) are more expensive and take longer to complete than in "corporatist" European systems (France, Germany, Spain). The core argument can be broken down into several interconnected parts:

The Problem: Infrastructure Planning Sclerosis

The article uses the example of the "bat shed" - a £100 million structure built to protect bats as part of the UK's HS2 rail project - to illustrate how seemingly minor environmental concerns can dramatically inflate infrastructure costs. This represents a broader pattern of "planning sclerosis" where infrastructure projects face excessive delays and costs.

Two Competing Models of Planning Failure

The "Swiss Cheese" Model: This conventional view suggests that objections to infrastructure projects are exogenous (externally generated). Environmental regulations provide "raw material" for opponents who throw objections at development processes to derail them. In this view, the solution would be to reduce regulations or streamline approval processes.

The "Problem Factory" Model: The article argues this is more accurate. In this model, objections are not fixed or objective but are industrial products created by the professional services industry (lawyers, consultants, environmental specialists). The key insight is that the "problem factory" and "solution factory" are not separate operations but are deeply interconnected and synergistic.

Preemptive Risk Aversion

The article identifies a crucial mechanism: "preemptive risk aversion." Infrastructure developers face enormous risks if their projects are rejected, so they attempt to "bulletproof" projects by addressing every conceivable objection in advance, no matter how unlikely. This leads to:

Expensive mitigation measures (like the £100 million bat shed)

Extensive documentation and studies

Lengthy delays

The article argues this behavior is rational because in an adversarial system, any single unaddressed objection could potentially derail a multi-billion pound project.

Adversarial vs. Corporatist Systems

The core distinction the article makes is between:

Adversarial/Judicial Systems (Common Law countries):

Planning authorities act as neutral arbiters between developers and objectors

Limited capacity within planning authorities

Arms-length relationships governed by conflict-of-interest policies

Information flows through formal reports and evidence bundles

Decision-making is opaque with little opportunity to identify decisive factors in advance

Risk of judicial review creates uncertainty

Corporatist Systems (European countries):

The state takes a more active role in the planning process

Planning authorities have greater capacity and involvement

More integrated relationships between developers and authorities

Two-way information flows between all parties

More collaborative approach to problem-solving

Greater certainty about which issues need addressing

The Industrial Organization of Planning

A key insight is that most of the costly activity in planning happens in the private sector through networks of professional services firms. These firms:

Market both problems and solutions to developers

Constantly expand the "risk surface" by identifying new potential objections

Create standardized products and report templates

Spread awareness of new legal precedents and requirements

Crucially, the article argues that the main market for planning objections is not planning objectors (NIMBYs, environmentalists) but infrastructure developers themselves, who buy these services because they feel they have to mitigate every possible risk.

Why Traditional Solutions Fail

The article explains why typical "deregulatory" approaches fail. Since objections are produced within the system rather than being external hazards, simply reducing regulations doesn't solve the problem. As long as any environmental regulations exist, they can be shaped into objections by the professional services industry.

Proposed Solutions

Rather than importing corporatist systems wholesale, the article suggests working with the grain of Anglosphere economies by:

Having planning authorities hire their own professional services firms (paid for by developers)

Increasing secondments between private and public sectors

Building more institutional knowledge within planning authorities

Creating more two-way dialogue in the planning process

This would address the information bottleneck and reduce uncertainty without fundamentally changing the adversarial nature of the system.

The article concludes by noting the paradox that one of the Anglosphere's great strengths (a vibrant professional services industry) is closely linked to one of its weaknesses (slow and expensive infrastructure procurement).

Klimt

Has the Rise of Work from Home Reduced the Motherhood Penalty in the Labor Market?

Abstract: When women become mothers, they often take a step back from their careers. Could work from home (WFH) reduce this motherhood penalty, particularly in traditionally family-unfriendly careers? We leverage technological changes prior to the pandemic that increased the feasibility of WFH in some college degrees but not others. In degrees where WFH increased, motherhood gaps in employment narrowed: for every 10% increase in WFH, mothers’ employment rates increased by 0.78 per centage points (or 0.94%) relative to other women’s. This change is driven by majors linked to careers that have high returns to hours and inflexible demands on workers’ time. We microfound these results using panel data that show that women who could WFH before childbirth are less likely to exit the workforce.

The HS2 debacle

The English have their whipping boy The Establishment. It may be worse than us, but we’ve certainly got many of the same features. Political adversarialism means conceptual chaos - with policies being made on the way to business lunches or other events where it would be handy to announce something. It’s now pretty standard in Victoria whenever government changes hands for the new party of government to hand over a few billion to infrastructure developers who are paid off so the incoming party can upend the infrastructure priorities of the outgoing one - mid project. An obviously disastrous state of affairs.

I wonder how much longer we’ll get by with Churchill’s line that democracy is the worst form of government except for all the alternatives that have been tried. Those costs really are very deep. And here’s the kicker. He’s right that the alternatives to democracy might be worse than what we have, but elections aren’t the only way to do representative democracy as the Athenians knew. Selection by lot is way less crazy and forms the perfect check and balance, the perfect stabiliser and centre for our system. But I would say that wouldn’t I.

The budgetary chaos that has overwhelmed the UK's High Speed 2 (HS2) project should lead to a period of deep reflection within the transport industry. It highlights a profound lack of economic, and even arithmetical, seriousness among Britain's political elite. Sally Gimson has done the public a great service by setting out clearly and succinctly the chronology of woolly thinking that has led to the current debacle – a high-speed railway barely one third complete that may actually result in slower journey times for many passengers, the final cost of which remains unknowable.

This is a story of equal-opportunities failure to which every part of the British establishment has contributed. It tells us much about the wider state of the country's governance structures, leadership class and politics...

After an express run through 150 years of railway history, Gimson details the HS2 story with commendable clarity. The project was hatched by New Labour's top egghead, Andrew Adonis, a former Financial Times journalist and fellow of Nuffield College, Oxford. Like his intellectual hero Roy Jenkins, Adonis is an ardent admirer of anything 'European', though his greatest passion is for trains à grande vitesse rather than the finer clarets. Adonis made the mistake of failing at the outset to set clear objectives for the project, other than the vague desire to modernise Britain's railways. Long after Adonis's departure, a lack of clear purpose remained at the root of the project...

The central fact about Britain's geography is that at least 40 per cent of the population lives in a quadrangle formed by London, Bristol, Liverpool and Leeds. These places are too closely located to one another for French-style high-speed rail to deliver transformational journey-time advantages. The route from Paris to Lyon measures around four hundred kilometres, which is generally considered the optimal length for high-speed rail. The distance between London and Birmingham, by contrast, is only around 160 kilometres, while London and Manchester are around 260 kilometres apart...

Once the project got under way, the routing and specifications constantly changed in response to endless consultations and lobbying. High Speed 1 (HS1), the line between St Pancras and the Channel Tunnel, may have underperformed in terms of passenger demand, but it was built quickly, using standard French technology dating back to the 1980s. For reasons that are unclear, HS2 has adopted totally different standards and speeds – another contributor to its massive cost, which started at £38 billion and may now stand at £80 billion for the London–Birmingham route (HS1, by contrast, cost around £7 billion)...

HS2 is supposed to bring national renewal, but those who have orchestrated the chaos seem to have no coherent model of economics, and certainly no conception of planning as an exercise in evidence-gathering and trade-offs. A large part of the blame lies with Britain's political class, which comprises a narrow pool of upper-middle-class types who share many of the same vague assumptions... Gimson observes, 'there are real questions about whether the British political system is conducive to evaluating complex infrastructure projects like high-speed rail. Much of the discussion in Parliament is adversarial, led by humanities graduates and accountants who pride themselves on winning clever arguments rather than focusing on the national interest.'

Faith in received opinion is not confined to one side of politics. HS2's cheerleaders – Adonis, George Osborne, Boris Johnson – share greater similarities in outlook, if not personality, than any of them might admit...

As someone who has devoted his entire working life to transport, I remain unclear as to why people hold this view so strongly. The facts are far more nuanced... The USA, which has very little high-speed rail, has outperformed Europe on most economic measures for decades. None of this is to say that high-speed rail can have no positive role in economic development, but it is far from clear that projects like HS2 represent best-value interventions. Improving the economy of northern England is just as likely to come from enhancing intra-regional rail services, raising skills levels and reducing business taxes and red tape.

A recurrent aspect of this tale, with implications far beyond HS2, is the insufficient thought given to incentives. The idea that people and organisations might respond to incentives seems quite alien to Britain's leadership class... By far the biggest distortion arises from the ability, described by Gimson at length, of MPs, peers, quangos and single-purpose agencies (like Natural England) to impose massive scope changes and effectively bill the Treasury for them. The cost-plus construction contracts used for HS2 are an economic doomsday machine, bound to lead to scope inflation, waste and delay.

Off the Rails is not the definitive history of HS2, but Gimson has clearly set out the sequence of decisions that have brought into being the meteorite-sized craters that lie between London and Birmingham, and the equally massive hole in the public finances. Read this book with a stiff drink.

Caption competition

How The Leopard changed its spots

I loved the Netflix Leopard, but largely for the costumes and sets. Though I’d not read The Leopard, the mini-series pacing through time didn’t really make sense with generational reappraisals occurring within a few years. Anyway, I enjoyed this piece from Inside Story which is also amusingly written. But it’s around 2,000 words long so the extract below is just a tease. Go check it out.

Centuries of marauding foreign invaders; poor infrastructure; organised crime networks; high unemployment — hasn't Sicily suffered enough? Then along comes Netflix's adaptation of Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa's 1958 classic, The Leopard, to inflict real pain on a region with every right to feel protective of one of its most significant contributions to Italian culture.

It's not that it was necessarily wrong for the streaming giant to ferret out what's arguably the best intellectual property Italy has on offer — after all, there's a limit to how many adaptations of Pinocchio audiences can tolerate...

What Sicilians would be entitled to resent is the mischaracterisation [of] the main character: don Fabrizio Corbera, Prince of Salina. The novel is built around Salina's worldview; if you get that wrong, nothing else makes much sense in the story's world.

Despite the novel's famous and often misunderstood refrain, "If we want everything to remain as it is, everything has to change," Lampedusa's Salina has already come to terms with the unstoppable rise of the new mafia-tinged middle class that now holds the money and, with it, the power. He has already surrendered to history...

In the six-part Netflix series, which includes both a padded-out version of the novel's events and an imagined sequel, Salina is a tough guy desperate to push back. We seem him humiliating the local mafia middleman for stealing baskets of fruit from his properties and then making him an offer he can't refuse...

The Salina of the novel would be the last to know if his employees were pilfering fruit. He's a man of letters and science, usually holed up in his observatory talking astronomy with his sparring partner, Father Pirrone. He's already reconciled to the fact that he's bleeding money to cashed-up commoners, and he has decided not to fight back...

Lampedusa's Salina tells the reader that the descendants of his Norman ancestors may have been around for centuries but now the game is over. What money they have will be lost within a few generations — namely, the very generation of the book's author, who preferred to watch his family home crumble around him during the mid twentieth century than suffer the indignity of getting a real job. You can't write books sipping coffee in Palermo's Bar Mazzara, around the corner from the magnificent Teatro Massimo, if you need a nine-to-five just to pay for the kids' tennis lessons...

And, of course, Salina in the novel isn't referred to as "the Leopard." It's not a nickname. The title of the book, Il Gattopardo, is a reference to the serval, or leopard, of the family's coat of arms... In the series, everyone refers to Salina as "the leopard," like he was a bejewelled rapper with an aka...

The mystical view of Sicily that underpins the novel is also what has made it so controversial. Leonardo Sciascia, whose writing has come to define the island, argued that The Leopard's description of a society immobilised by its inability to accept change fails to grapple with the real impact of the Risorgimento — the political movement that brought about the unification of Italy...

Today, there's no shortage of Sicilian writers and thinkers who would agree with that assessment of The Leopard's deep conservatism... But to believe this is to reject the very premise of The Leopard, which can only be read as a depiction of a society in which no ruler and no state authority can bring about change.

Great piece

Dependence: From whence we came, to where we’re going

A cri de coeur from a religious man apparently living a life of service.

Human beings don't like to be dependent. If you've ever broken a bone or had some other temporary physical impediment, you know that it is difficult to accept someone else's help, no matter how gracious they may be in giving. And we recognize that some types of dependence can be pernicious: When a person relies on others such that his or her emotional well-being hinges on external acceptance and validation, psychiatrists call it "dependent personality disorder."

All of us were born dependent and remained so for years; most of us will experience a period of decline before we die when we'll once again become dependent on others. Indeed, the American bioethicist and theologian Gilbert Meilaender described a trajectory or arc of life, where we begin and end our lives dependent on others but spend a great deal of time much less so—and one of the things that we do with that freedom is care for those who are dependent...

But if we become uneasy at the thought of physically depending on others, dependency on others because of a deficiency in our mental capacity is terrifying. Half of those who live to age 85 will develop some kind of dementia; perhaps 1 to 2 percent of people have a congenital or acquired intellectual disability—like Down syndrome or a major traumatic brain injury—so severe that they are dependent on others' care for their entire lives. In a culture like ours that prizes rational thought and self-sufficiency, we are especially anxious about the idea of losing those things.

The push for euthanasia across the Western world is predicated on this fear. People do not want to be "a burden" to their loved ones, so much so that they choose to die rather than suffer the indignities they associate with dependence. Canada has taken this logic to a grim extreme by euthanizing people who are merely poor and dependent on government welfare, while other countries like Belgium permit the suicide of those with severe mental illness...

But one of the more challenging topics when it comes to dependence is dealing with the wider penumbra of people who have milder disabilities, physical or mental, that prevent them from achieving complete independence as adults...

Many people would like to believe that a more just society with an abundance of resources available for the poorest and most mentally ill people would make such institutionalization unnecessary. It is true some of the people who are most vulnerable are helped greatly by models such as "Housing First," which gives them a safe place while they try to get their lives back on track. But it is unclear that this is a global strategy that works for everyone, and people can still pose a huge risk to themselves or others even when they are housed and cared for.

The left-liberal instinct to hope that we can manipulate policies and structures in order to eliminate the need for long-term institutionalization is just a reflection of a much broader and more instinctual fear we all have. None of us wants to countenance the possibility that our mental faculties might deteriorate to the point that we'll need to be dependent on others, because to do so is to surrender one of the greatest privileges of being an adult human...

In a culture like ours that prizes rational thought and self-sufficiency, we are especially anxious about the idea of losing those things.

It's even worse in our day and age, when technology has liberated us from many other frailties and limits. It takes us hours to cross distances that took our ancestors months, we can ward off deadly diseases with a tiny injection of fluid, and the calories we need to survive are produced in such abundance it would have struck medieval kings dumb. The fact that medical science has yet to develop tools for the mind as potent as artificial limbs or other adaptive devices makes the happenstances of mental infirmity feel especially cruel...

There's another great Gilbert Meilaender line worth quoting: "I want to burden my loved ones." The brief spasm of horror you may have felt reading that sentence is the fear of dependence inculcated in each of us that is good when you are capable of doing something for yourself but bad when you are incapable. All of us have been incapable at one point in our lives, most of us will be incapable at some point in our lives, and a handful of us are born or become permanently incapable throughout our entire lives...

On an individual, social, and cultural level we can never escape the need for dependence on others. Such dependence is part of the natural progression of every human life at the beginning, most human lives at the end, and quite a few throughout. Like Meilaender, we should look forward to being a burden because there is a joy not only in serving others, but in being served by our fellow human beings...

Acknowledging these realities is the first step in dealing with some of the most pernicious challenges involving human dignity right now, whether it's people so lost in the quicksand that their lives are at risk or the people whose lives feel so bleak that a government-sponsored set of cement shoes seems like a good idea. If we don't celebrate the joy of dependence, we will find ourselves in a society that treats the burdensome viciously—even as it finds more and more of them to be a burden.

Is it about mattering or a gamed system?

Will Storr has written a well-regarded book called The Status Game which explores just how status conscious we are. People I respect say it’s a good book, but I’ve not read it. And this article is in a similar vein. His conclusion is pessimistic bordering on nihilistic. With billions of people in the world our craving for importance can’t be met. I get the idea, and simple ideas are good ones when it comes to understanding us humangoes. But I can’t help thinking that people like being a small part in something, if they have faith in that something, if they think it’s something to which they can give their loyalty, their allegiance.

Now you can argue that, in demystifying, or as Max Weber might say, disenchanting those things, we’re out in the cold. We’ve seen through the noble lie and it’s done us in. But I can’t help think that our disenchantment is a direct result of living in the world Alasdair MacIntyre warned us we were building.

In any society which recognized only external goods, competitiveness would be the dominant and even exclusive feature… We should therefore expect that, if in a particular society the pursuit of external goods were to become dominant, the concept of the virtues might suffer first attrition and then perhaps something near total effacement, although simulacra might abound.

I also think it’s possible to build a world much less like that without simply caving to a hankering for a world that’s gone - which wouldn’t work anyway. I think we can do it with simple institutions. I can’t prove it, but then Will Storr can’t prove his bleak understanding of the problem is right either.

For billions of people around the world, life has been perfected. We have food, clean water, shelter, warmth and elaborate systems of protection that take care of us when we fall sick or fail. We live in freedom, not tyranny, and sleep in comfortable beds with entertainment everywhere. From the perspective of the humans of 10,000 years ago or 1,000 years ago or 200 years ago, we are living the lives of gods. Truly, in 2025, we have created a heaven on earth for the masses.

But we are not happy.

What is that restless yearning we bring with us on the routines of our days? Heavy yet empty, it gnaws, a species of hunger, something dissatisfied. It's not always there. I notice mine mainly on the ordinary days which, by definition, are most of them; sometimes distant, sometimes crushing, never far away...

We are not happy because we're hunter-gatherers living in a runaway environment that fails to provide us with sufficient amounts of some of life's essential elements.

And we are still hunter-gatherers. Humans spent at least 100,000 generations living in small, mobile groups, and it's in these groups in which we evolved. We only started settling down at the dawn of agriculture, about 500 generations ago. Our brains haven't had the chance to catch up with our spectacularly altered circumstances...

By modern standards, our social reality back then was unimaginably tiny. The number often quoted as the size of our ancestral tribes is 150, but this would have included the wider group, with whom our association was relatively sporadic. Day-to-day life, for well over 95 per cent of our existence on this planet, was spent in the company of between 25 and 35 people.

And our social reality was everything. Humans are a species of ultra-social ape – a unique kind of chimpanzee-ant crossbreed – that solved the problems of survival by working together in highly-cooperative groups...

In the forager camps of our long evolutionary past, these essential social nutrients would have been relatively easy to come by. We would have had to maintain secure connection with just a few dozen souls...

And then, over the past 11,000 years or so, this changed. As the world got bigger, our importance shrank. We began to matter less.

It all started when we settled down into villages – and then towns, and then cities, and then nations. Over the last 500 generations, our groups have become remorselessly larger... We work in crowds and we travel home in crowds and we sleep surrounded by crowds of sleeping people. Population densities today are up to 100,000 times greater than they were in our forager past...

We're programmed to want to feel as if our existence is important, even essential. For millions of years, it likely would have been. But in the modern West, how often do we feel indispensable?... This is not a conspiracy. It might be narratively satisfying to blame capitalists and tech bros as if they're calculating cartoon villains, but none of them plotted to create our crisis of mattering. The West was made inch by inch by ambitious, experimenting individuals who led groups that played status games.

Here. I write to you at 16.14 on the 13th June 2025 in room 419 of the Premier Inn in Sheffield, England. I am sitting in front of my laptop eating a Gregg's sausage roll and drinking a Gregg's Fairtrade Apple Juice... Tomorrow I will speak to some Humanists at a Humanist conference and I don't know what a Humanist is or what the Humanists want from me. I am tired and my heart hurts and I ache and I am well fed and I am well watered... Later I will walk through the Friday night summer streets and the bars and the clubs and the restaurants will be filled with restless Friday night people and the girls will look like sex and the boys will look like violence and they all, more than anything, want to feel that they matter, they matter, they matter, and they will feel that way, and then they won't.

Heaviosity half hour

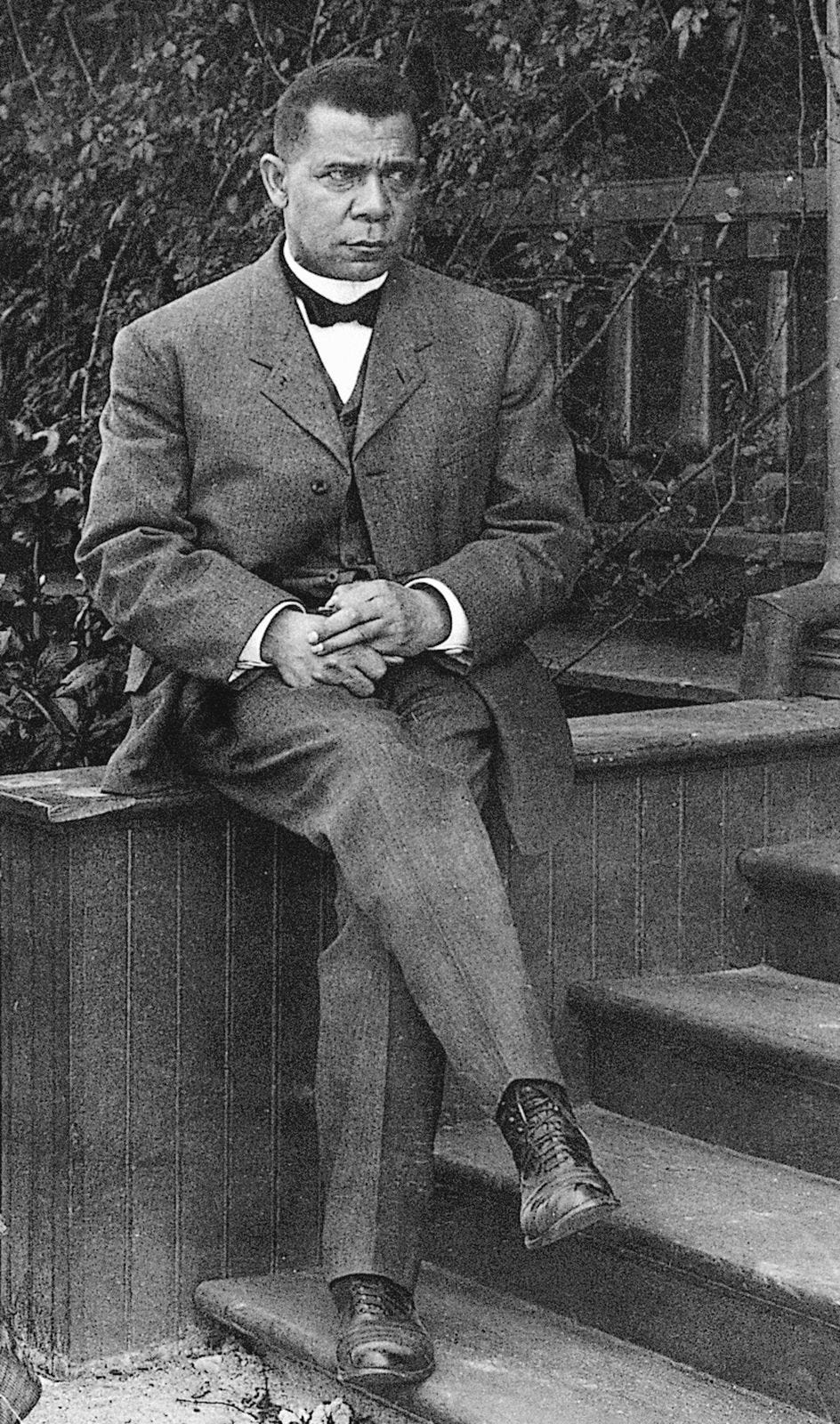

Up from slavery: Booker T. Washington

Chapter I: A Slave Among Slaves

I was born a slave on a plantation in Franklin County, Virginia. I am not quite sure of the exact place or exact date of my birth, but at any rate I suspect I must have been born somewhere and at some time. As nearly as I have been able to learn, I was born near a cross-roads post-office called Hale’s Ford, and the year was 1858 or 1859. I do not know the month or the day. The earliest impressions I can now recall are of the plantation and the slave quarters—the latter being the part of the plantation where the slaves had their cabins.

My life had its beginning in the midst of the most miserable, desolate, and discouraging surroundings. This was so, however, not because my owners were especially cruel, for they were not, as compared with many others. I was born in a typical log cabin, about fourteen by sixteen feet square. In this cabin I lived with my mother and a brother and sister till after the Civil War, when we were all declared free.

Of my ancestry I know almost nothing. In the slave quarters, and even later, I heard whispered conversations among the coloured people of the tortures which the slaves, including, no doubt, my ancestors on my mother’s side, suffered in the middle passage of the slave ship while being conveyed from Africa to America. I have been unsuccessful in securing any information that would throw any accurate light upon the history of my family beyond my mother. She, I remember, had a half-brother and a half-sister. In the days of slavery not very much attention was given to family history and family records—that is, black family records. My mother, I suppose, attracted the attention of a purchaser who was afterward my owner and hers. Her addition to the slave family attracted about as much attention as the purchase of a new horse or cow. Of my father I know even less than of my mother. I do not even know his name. I have heard reports to the effect that he was a white man who lived on one of the near-by plantations. Whoever he was, I never heard of his taking the least interest in me or providing in any way for my rearing. But I do not find especial fault with him. He was simply another unfortunate victim of the institution which the Nation unhappily had engrafted upon it at that time.

The cabin was not only our living-place, but was also used as the kitchen for the plantation. My mother was the plantation cook. The cabin was without glass windows; it had only openings in the side which let in the light, and also the cold, chilly air of winter. There was a door to the cabin—that is, something that was called a door—but the uncertain hinges by which it was hung, and the large cracks in it, to say nothing of the fact that it was too small, made the room a very uncomfortable one. In addition to these openings there was, in the lower right-hand corner of the room, the “cat-hole,”—a contrivance which almost every mansion or cabin in Virginia possessed during the ante-bellum period. The “cat-hole” was a square opening, about seven by eight inches, provided for the purpose of letting the cat pass in and out of the house at will during the night. In the case of our particular cabin I could never understand the necessity for this convenience, since there were at least a half-dozen other places in the cabin that would have accommodated the cats. There was no wooden floor in our cabin, the naked earth being used as a floor. In the centre of the earthen floor there was a large, deep opening covered with boards, which was used as a place in which to store sweet potatoes during the winter. An impression of this potato-hole is very distinctly engraved upon my memory, because I recall that during the process of putting the potatoes in or taking them out I would often come into possession of one or two, which I roasted and thoroughly enjoyed. There was no cooking-stove on our plantation, and all the cooking for the whites and slaves my mother had to do over an open fireplace, mostly in pots and “skillets.” While the poorly built cabin caused us to suffer with cold in the winter, the heat from the open fireplace in summer was equally trying.

The early years of my life, which were spent in the little cabin, were not very different from those of thousands of other slaves. My mother, of course, had little time in which to give attention to the training of her children during the day. She snatched a few moments for our care in the early morning before her work began, and at night after the day’s work was done. One of my earliest recollections is that of my mother cooking a chicken late at night, and awakening her children for the purpose of feeding them. How or where she got it I do not know. I presume, however, it was procured from our owner’s farm. Some people may call this theft. If such a thing were to happen now, I should condemn it as theft myself. But taking place at the time it did, and for the reason that it did, no one could ever make me believe that my mother was guilty of thieving. She was simply a victim of the system of slavery. I cannot remember having slept in a bed until after our family was declared free by the Emancipation Proclamation. Three children—John, my older brother, Amanda, my sister, and myself—had a pallet on the dirt floor, or, to be more correct, we slept in and on a bundle of filthy rags laid upon the dirt floor.

I was asked not long ago to tell something about the sports and pastimes that I engaged in during my youth. Until that question was asked it had never occurred to me that there was no period of my life that was devoted to play. From the time that I can remember anything, almost every day of my life had been occupied in some kind of labour; though I think I would now be a more useful man if I had had time for sports. During the period that I spent in slavery I was not large enough to be of much service, still I was occupied most of the time in cleaning the yards, carrying water to the men in the fields, or going to the mill to which I used to take the corn, once a week, to be ground. The mill was about three miles from the plantation. This work I always dreaded. The heavy bag of corn would be thrown across the back of the horse, and the corn divided about evenly on each side; but in some way, almost without exception, on these trips, the corn would so shift as to become unbalanced and would fall off the horse, and often I would fall with it. As I was not strong enough to reload the corn upon the horse, I would have to wait, sometimes for many hours, till a chance passer-by came along who would help me out of my trouble. The hours while waiting for some one were usually spent in crying. The time consumed in this way made me late in reaching the mill, and by the time I got my corn ground and reached home it would be far into the night. The road was a lonely one, and often led through dense forests. I was always frightened. The woods were said to be full of soldiers who had deserted from the army, and I had been told that the first thing a deserter did to a Negro boy when he found him alone was to cut off his ears. Besides, when I was late in getting home I knew I would always get a severe scolding or a flogging.

I had no schooling whatever while I was a slave, though I remember on several occasions I went as far as the schoolhouse door with one of my young mistresses to carry her books. The picture of several dozen boys and girls in a schoolroom engaged in study made a deep impression upon me, and I had the feeling that to get into a schoolhouse and study in this way would be about the same as getting into paradise.

So far as I can now recall, the first knowledge that I got of the fact that we were slaves, and that freedom of the slaves was being discussed, was early one morning before day, when I was awakened by my mother kneeling over her children and fervently praying that Lincoln and his armies might be successful, and that one day she and her children might be free. In this connection I have never been able to understand how the slaves throughout the South, completely ignorant as were the masses so far as books or newspapers were concerned, were able to keep themselves so accurately and completely informed about the great National questions that were agitating the country. From the time that Garrison, Lovejoy, and others began to agitate for freedom, the slaves throughout the South kept in close touch with the progress of the movement. Though I was a mere child during the preparation for the Civil War and during the war itself, I now recall the many late-at-night whispered discussions that I heard my mother and the other slaves on the plantation indulge in. These discussions showed that they understood the situation, and that they kept themselves informed of events by what was termed the “grape-vine” telegraph.

During the campaign when Lincoln was first a candidate for the Presidency, the slaves on our far-off plantation, miles from any railroad or large city or daily newspaper, knew what the issues involved were. When war was begun between the North and the South, every slave on our plantation felt and knew that, though other issues were discussed, the primal one was that of slavery. Even the most ignorant members of my race on the remote plantations felt in their hearts, with a certainty that admitted of no doubt, that the freedom of the slaves would be the one great result of the war, if the Northern armies conquered. Every success of the Federal armies and every defeat of the Confederate forces was watched with the keenest and most intense interest. Often the slaves got knowledge of the results of great battles before the white people received it. This news was usually gotten from the coloured man who was sent to the post-office for the mail. In our case the post-office was about three miles from the plantation, and the mail came once or twice a week. The man who was sent to the office would linger about the place long enough to get the drift of the conversation from the group of white people who naturally congregated there, after receiving their mail, to discuss the latest news. The mail-carrier on his way back to our master’s house would as naturally retail the news that he had secured among the slaves, and in this way they often heard of important events before the white people at the “big house,” as the master’s house was called.

I cannot remember a single instance during my childhood or early boyhood when our entire family sat down to the table together, and God’s blessing was asked, and the family ate a meal in a civilized manner. On the plantation in Virginia, and even later, meals were gotten by the children very much as dumb animals get theirs. It was a piece of bread here and a scrap of meat there. It was a cup of milk at one time and some potatoes at another. Sometimes a portion of our family would eat out of the skillet or pot, while some one else would eat from a tin plate held on the knees, and often using nothing but the hands with which to hold the food. When I had grown to sufficient size, I was required to go to the “big house” at meal-times to fan the flies from the table by means of a large set of paper fans operated by a pulley. Naturally much of the conversation of the white people turned upon the subject of freedom and the war, and I absorbed a good deal of it. I remember that at one time I saw two of my young mistresses and some lady visitors eating ginger-cakes, in the yard. At that time those cakes seemed to me to be absolutely the most tempting and desirable things that I had ever seen; and I then and there resolved that, if I ever got free, the height of my ambition would be reached if I could get to the point where I could secure and eat ginger-cakes in the way that I saw those ladies doing.

Of course as the war was prolonged the white people, in many cases, often found it difficult to secure food for themselves. I think the slaves felt the deprivation less than the whites, because the usual diet for slaves was corn bread and pork, and these could be raised on the plantation; but coffee, tea, sugar, and other articles which the whites had been accustomed to use could not be raised on the plantation, and the conditions brought about by the war frequently made it impossible to secure these things. The whites were often in great straits. Parched corn was used for coffee, and a kind of black molasses was used instead of sugar. Many times nothing was used to sweeten the so-called tea and coffee.

The first pair of shoes that I recall wearing were wooden ones. They had rough leather on the top, but the bottoms, which were about an inch thick, were of wood. When I walked they made a fearful noise, and besides this they were very inconvenient, since there was no yielding to the natural pressure of the foot. In wearing them one presented an exceedingly awkward appearance. The most trying ordeal that I was forced to endure as a slave boy, however, was the wearing of a flax shirt. In the portion of Virginia where I lived it was common to use flax as part of the clothing for the slaves. That part of the flax from which our clothing was made was largely the refuse, which of course was the cheapest and roughest part. I can scarcely imagine any torture, except, perhaps, the pulling of a tooth, that is equal to that caused by putting on a new flax shirt for the first time. It is almost equal to the feeling that one would experience if he had a dozen or more chestnut burrs, or a hundred small pin-points, in contact with his flesh. Even to this day I can recall accurately the tortures that I underwent when putting on one of these garments. The fact that my flesh was soft and tender added to the pain. But I had no choice. I had to wear the flax shirt or none; and had it been left to me to choose, I should have chosen to wear no covering. In connection with the flax shirt, my brother John, who is several years older than I am, performed one of the most generous acts that I ever heard of one slave relative doing for another. On several occasions when I was being forced to wear a new flax shirt, he generously agreed to put it on in my stead and wear it for several days, till it was “broken in.” Until I had grown to be quite a youth this single garment was all that I wore.

One may get the idea, from what I have said, that there was bitter feeling toward the white people on the part of my race, because of the fact that most of the white population was away fighting in a war which would result in keeping the Negro in slavery if the South was successful. In the case of the slaves on our place this was not true, and it was not true of any large portion of the slave population in the South where the Negro was treated with anything like decency. During the Civil War one of my young masters was killed, and two were severely wounded. I recall the feeling of sorrow which existed among the slaves when they heard of the death of “Mars’ Billy.” It was no sham sorrow, but real. Some of the slaves had nursed “Mars’ Billy”; others had played with him when he was a child. “Mars’ Billy” had begged for mercy in the case of others when the overseer or master was thrashing them. The sorrow in the slave quarter was only second to that in the “big house.” When the two young masters were brought home wounded, the sympathy of the slaves was shown in many ways. They were just as anxious to assist in the nursing as the family relatives of the wounded. Some of the slaves would even beg for the privilege of sitting up at night to nurse their wounded masters. This tenderness and sympathy on the part of those held in bondage was a result of their kindly and generous nature. In order to defend and protect the women and children who were left on the plantations when the white males went to war, the slaves would have laid down their lives. The slave who was selected to sleep in the “big house” during the absence of the males was considered to have the place of honour. Any one attempting to harm “young Mistress” or “old Mistress” during the night would have had to cross the dead body of the slave to do so. I do not know how many have noticed it, but I think that it will be found to be true that there are few instances, either in slavery or freedom, in which a member of my race has been known to betray a specific trust.

As a rule, not only did the members of my race entertain no feelings of bitterness against the whites before and during the war, but there are many instances of Negroes tenderly caring for their former masters and mistresses who for some reason have become poor and dependent since the war. I know of instances where the former masters of slaves have for years been supplied with money by their former slaves to keep them from suffering. I have known of still other cases in which the former slaves have assisted in the education of the descendants of their former owners. I know of a case on a large plantation in the South in which a young white man, the son of the former owner of the estate, has become so reduced in purse and self-control by reason of drink that he is a pitiable creature; and yet, notwithstanding the poverty of the coloured people themselves on this plantation, they have for years supplied this young white man with the necessities of life. One sends him a little coffee or sugar, another a little meat, and so on. Nothing that the coloured people possess is too good for the son of “old Mars’ Tom,” who will perhaps never be permitted to suffer while any remain on the place who knew directly or indirectly of “old Mars’ Tom.”

I have said that there are few instances of a member of my race betraying a specific trust. One of the best illustrations of this which I know of is in the case of an ex-slave from Virginia whom I met not long ago in a little town in the state of Ohio. I found that this man had made a contract with his master, two or three years previous to the Emancipation Proclamation, to the effect that the slave was to be permitted to buy himself, by paying so much per year for his body; and while he was paying for himself, he was to be permitted to labour where and for whom he pleased. Finding that he could secure better wages in Ohio, he went there. When freedom came, he was still in debt to his master some three hundred dollars. Notwithstanding that the Emancipation Proclamation freed him from any obligation to his master, this black man walked the greater portion of the distance back to where his old master lived in Virginia, and placed the last dollar, with interest, in his hands. In talking to me about this, the man told me that he knew that he did not have to pay the debt, but that he had given his word to the master, and his word he had never broken. He felt that he could not enjoy his freedom till he had fulfilled his promise.

From some things that I have said one may get the idea that some of the slaves did not want freedom. This is not true. I have never seen one who did not want to be free, or one who would return to slavery.

I pity from the bottom of my heart any nation or body of people that is so unfortunate as to get entangled in the net of slavery. I have long since ceased to cherish any spirit of bitterness against the Southern white people on account of the enslavement of my race. No one section of our country was wholly responsible for its introduction, and, besides, it was recognized and protected for years by the General Government. Having once got its tentacles fastened on to the economic and social life of the Republic, it was no easy matter for the country to relieve itself of the institution. Then, when we rid ourselves of prejudice, or racial feeling, and look facts in the face, we must acknowledge that, notwithstanding the cruelty and moral wrong of slavery, the ten million Negroes inhabiting this country, who themselves or whose ancestors went through the school of American slavery, are in a stronger and more hopeful condition, materially, intellectually, morally, and religiously, than is true of an equal number of black people in any other portion of the globe. This is so to such an extent that Negroes in this country, who themselves or whose forefathers went through the school of slavery, are constantly returning to Africa as missionaries to enlighten those who remained in the fatherland. This I say, not to justify slavery—on the other hand, I condemn it as an institution, as we all know that in America it was established for selfish and financial reasons, and not from a missionary motive—but to call attention to a fact, and to show how Providence so often uses men and institutions to accomplish a purpose. When persons ask me in these days how, in the midst of what sometimes seem hopelessly discouraging conditions, I can have such faith in the future of my race in this country, I remind them of the wilderness through which and out of which, a good Providence has already led us.

Ever since I have been old enough to think for myself, I have entertained the idea that, notwithstanding the cruel wrongs inflicted upon us, the black man got nearly as much out of slavery as the white man did. The hurtful influences of the institution were not by any means confined to the Negro. This was fully illustrated by the life upon our own plantation. The whole machinery of slavery was so constructed as to cause labour, as a rule, to be looked upon as a badge of degradation, of inferiority. Hence labour was something that both races on the slave plantation sought to escape. The slave system on our place, in a large measure, took the spirit of self-reliance and self-help out of the white people. My old master had many boys and girls, but not one, so far as I know, ever mastered a single trade or special line of productive industry. The girls were not taught to cook, sew, or to take care of the house. All of this was left to the slaves. The slaves, of course, had little personal interest in the life of the plantation, and their ignorance prevented them from learning how to do things in the most improved and thorough manner. As a result of the system, fences were out of repair, gates were hanging half off the hinges, doors creaked, window-panes were out, plastering had fallen but was not replaced, weeds grew in the yard. As a rule, there was food for whites and blacks, but inside the house, and on the dining-room table, there was wanting that delicacy and refinement of touch and finish which can make a home the most convenient, comfortable, and attractive place in the world. Withal there was a waste of food and other materials which was sad. When freedom came, the slaves were almost as well fitted to begin life anew as the master, except in the matter of book-learning and ownership of property. The slave owner and his sons had mastered no special industry. They unconsciously had imbibed the feeling that manual labour was not the proper thing for them. On the other hand, the slaves, in many cases, had mastered some handicraft, and none were ashamed, and few unwilling, to labour.

Finally the war closed, and the day of freedom came. It was a momentous and eventful day to all upon our plantation. We had been expecting it. Freedom was in the air, and had been for months. Deserting soldiers returning to their homes were to be seen every day. Others who had been discharged, or whose regiments had been paroled, were constantly passing near our place. The “grape-vine telegraph” was kept busy night and day. The news and mutterings of great events were swiftly carried from one plantation to another. In the fear of “Yankee” invasions, the silverware and other valuables were taken from the “big house,” buried in the woods, and guarded by trusted slaves. Woe be to any one who would have attempted to disturb the buried treasure. The slaves would give the Yankee soldiers food, drink, clothing—anything but that which had been specifically intrusted to their care and honour. As the great day drew nearer, there was more singing in the slave quarters than usual. It was bolder, had more ring, and lasted later into the night. Most of the verses of the plantation songs had some reference to freedom. True, they had sung those same verses before, but they had been careful to explain that the “freedom” in these songs referred to the next world, and had no connection with life in this world. Now they gradually threw off the mask, and were not afraid to let it be known that the “freedom” in their songs meant freedom of the body in this world. The night before the eventful day, word was sent to the slave quarters to the effect that something unusual was going to take place at the “big house” the next morning. There was little, if any, sleep that night. All as excitement and expectancy. Early the next morning word was sent to all the slaves, old and young, to gather at the house. In company with my mother, brother, and sister, and a large number of other slaves, I went to the master’s house. All of our master’s family were either standing or seated on the veranda of the house, where they could see what was to take place and hear what was said. There was a feeling of deep interest, or perhaps sadness, on their faces, but not bitterness. As I now recall the impression they made upon me, they did not at the moment seem to be sad because of the loss of property, but rather because of parting with those whom they had reared and who were in many ways very close to them. The most distinct thing that I now recall in connection with the scene was that some man who seemed to be a stranger (a United States officer, I presume) made a little speech and then read a rather long paper—the Emancipation Proclamation, I think. After the reading we were told that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased. My mother, who was standing by my side, leaned over and kissed her children, while tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She explained to us what it all meant, that this was the day for which she had been so long praying, but fearing that she would never live to see.

For some minutes there was great rejoicing, and thanksgiving, and wild scenes of ecstasy. But there was no feeling of bitterness. In fact, there was pity among the slaves for our former owners. The wild rejoicing on the part of the emancipated coloured people lasted but for a brief period, for I noticed that by the time they returned to their cabins there was a change in their feelings. The great responsibility of being free, of having charge of themselves, of having to think and plan for themselves and their children, seemed to take possession of them. It was very much like suddenly turning a youth of ten or twelve years out into the world to provide for himself. In a few hours the great questions with which the Anglo-Saxon race had been grappling for centuries had been thrown upon these people to be solved. These were the questions of a home, a living, the rearing of children, education, citizenship, and the establishment and support of churches. Was it any wonder that within a few hours the wild rejoicing ceased and a feeling of deep gloom seemed to pervade the slave quarters? To some it seemed that, now that they were in actual possession of it, freedom was a more serious thing than they had expected to find it. Some of the slaves were seventy or eighty years old; their best days were gone. They had no strength with which to earn a living in a strange place and among strange people, even if they had been sure where to find a new place of abode. To this class the problem seemed especially hard. Besides, deep down in their hearts there was a strange and peculiar attachment to “old Marster” and “old Missus,” and to their children, which they found it hard to think of breaking off. With these they had spent in some cases nearly a half-century, and it was no light thing to think of parting. Gradually, one by one, stealthily at first, the older slaves began to wander from the slave quarters back to the “big house” to have a whispered conversation with their former owners as to the future.

I would contribute pure Dorothea Brooke mysticism to the idea of mattering. Even by desiring what is perfectly good an individual person can matter when many others will not even try.