Helping the disadvantaged (by cancelling them)

And other obscenities of late capitalism I found on the net this week

Something else Claudine Gay’s been up to

This is a documentary about the cancelling of Whiz Kid economist and John Bates Clark medalist (awarded to the best US economist under 40) Roland Fryer. I won’t disguise my own near-total sympathy with Fryer here. But being produced by a studio that describes itself as “a unique blend of edgy aesthetics, compelling storytelling, and conservative/libertarian politics”, I disliked the way the doco identified baddies for you, rather than show you stuff and let you make up your mind. In fact it’s even worse than that because the way the baddies are introduced as baddies with typical identity politics labels — ‘privileged’ and ‘liberal’. They are, and from what we’ve seen of Gay, she seems to me to be a pretty obvious diversity dud — but it’s a pity the producers didn’t just report the facts and let the viewer decide. Privileged people can be good people too.

Anyway, Fryer was doing fabulous work identifying all those things that are crucial to understanding entrenched disadvantage that it isn’t polite to talk about. He seems to have run a great research lab which was sufficiently rollicking that it offended some people. He did things that are today regarded as obviously inappropriate.

You’d never guess from the doco above that, as Wikipedia reports:

Fryer apologized for the "insensitive and inappropriate comments that led to my suspension", saying that he "didn't appreciate the inherent power dynamics in my interactions, which led me to act in ways that I now realize were deeply inappropriate for someone in my position."

As Fryer stresses, he never propositioned or bullied anyone. He should have been warned and given any additional training/support he may have needed. Instead, he was suspended without pay for two years, and his lab and all the excellent work it was doing was shut. It might not help with entrenched disadvantage, but you obviously can’t take any risks with middle-class proprieties.

It’s a pity all this is read through the grid of culture war. Even this interview — with culture warrior Bari Weiss — is very much in that vein, but you mostly hear Fryer in his own words. Why is he so fearless? Because, as he says, he doesn’t want the things that keep most people inside the electrified wire. He wants to help those in the kind of circumstances he was in.

Luxury beliefs anyone?

Rob Henderson has just published a memoirs of growing up as a foster kid and being shunted from pillar to post. He too is hostile to stories that encourage people to play the victim, or as he calls them ‘luxury beliefs’. If you’re unfamiliar with them, or with him, I recommend this podcast.

Oh and major bookshops won’t host launches of the book. It’s so much better to get advice on helping the disadvantaged from well-heeled folks rather than, you know … the disadvantaged!

And a review of the book

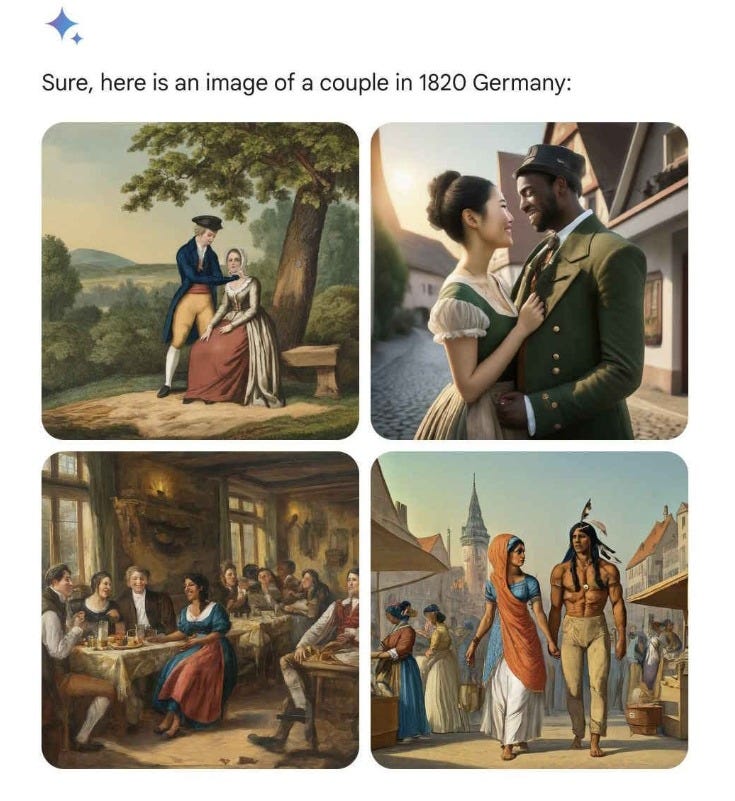

Anyway, it’s not all bad. We get diversified Nazis

War: radiating horror in all directions

Subscriber Will took exception to a comment by me that the numerous statements by Israelis including officials of the government that have been characterised as ‘incitements to genocide’ were “different to videos of sadistic killings and ringing up your Mum and saying "I feel so great I killed a few of them today!"” to which Will replied “Sadly, these videos very much exist also, there are lots of clips of IDF soldiers boasting about war crimes on Telegram”. And he provided the following links. I wasn’t sure they disproved my point, but I felt a bit silly saying so. They’re horrific, which I guess should surprise no one. War is horrific.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/06/world/middleeast/israel-idf-soldiers-war-social-media-video.html

Music to my ears

And, through all its deeply menacing potential, the one really good thing that might come from Donald Trump’s foray into politics. European independence.

Size tames Warren Buffett

In response to the various complaints of childhood, my Mum used to say to me “your troubles and Rockafella’s money”, which didn’t really mean anything to me at the time, but now Warren Buffett has the same kind of issue.

Our goal at Berkshire is simple: We want to own either all or a portion of businesses that enjoy good economics that are fundamental and enduring. Within capitalism, some businesses will flourish for a very long time while others will prove to be sinkholes. It’s harder than you would think to predict which will be the winners and losers. And those who tell you they know the answer are usually either self-delusional or snake-oil salesmen. At Berkshire, we particularly favor the rare enterprise that can deploy additional capital at high returns in the future. Owning only one of these companies – and simply sitting tight – can deliver wealth almost beyond measure. …

This combination of the two necessities I’ve described for acquiring businesses has for long been our goal in purchases and, for a while, we had an abundance of candidates to evaluate. If I missed one – and I missed plenty – another always came along.Those days are long behind us; size did us in, though increased competition for purchases was also a factor. Berkshire now has – by far – the largest GAAP net worth recorded by any American business. Record operating income and a strong stock market led to a yearend figure of $561 billion. The total GAAP net worth for the other 499 S&P companies – a who’s who of American business – was $8.9 trillion in 2022. (The 2023 number for the S&P has not yet been tallied but is

unlikely to materially exceed $9.5 trillion.)By this measure, Berkshire now occupies nearly 6% of the universe in which it operates. Doubling our huge base is simply not possible within, say, a five-year period … There remain only a handful of companies in this country capable of truly moving the needle at Berkshire, and they have been endlessly picked over by us and by others. Some we can value; some we can’t. And, if we can, they have to be attractively priced. Outside the U.S., there are essentially no candidates that are meaningful options for capital deployment at Berkshire. All in all, we have no possibility of eye-popping performance.

Nevertheless, managing Berkshire is mostly fun and always interesting. On the positive side, after 59 years of assemblage, the company now owns either a portion or 100% of various businesses that, on a weighted basis, have somewhat better prospects than exist at most large American companies. By both luck and pluck, a few huge winners have emerged from a great many dozens of decisions. And we now have a small cadre of long-time managers who never muse about going elsewhere and who regard 65 as just another birthday …

With that focus, and with our present mix of businesses, Berkshire should do a bit better than the average American corporation and, more important, should also operate with materially less risk of permanent loss of capital. Anything beyond “slightly better,” though, is wishful thinking.

Survival of the friendliest: seriously?

Here’s a new Substack discovery of mine, Dan Williams’ excellent, lengthy review of Survival of the Friendliest.

On just about any topic we care about our disagreements neatly arranged into right and left. This is nicely captured in the debate about evolution. Hard-headed types have nature ‘red in tooth and claw’, and genes are selfish. Meanwhile on the left we have people pointing out the evolutionary benefits of cooperation. There is no species whose members cooperate more, and more richly than us. Yet as this review makes clear, it’s much more complex than that.

Yes, we cooperate a lot, but it’s not a simple story, and it’s at least as much out of strategic self-interest as it is out of simple good-will. Even in families. I will say that I thought the review was a little too heavy on evolutionary language about strategic interaction, making it a little too easy to lose sight of the fact that almost all of this occurs at the level of culture, not biology. But while mapping the same kinds of arguments from biological to cultural evolution has its limits, it’s a very effective way to depart from the la la land of competition/bad, cooperation/good.

Once you grasp that cooperation can only be understood in terms of Darwinian organisms competing to maximise fitness, it becomes clear that human cooperation must involve much more complexity and strategy than indiscriminate friendliness towards an ingroup. …

First, there’s interdependence. In such cases, one organism, A, has a stake in the fitness of another, B, in the sense that A can promote its own fitness by helping B. There are many sources of interdependence in human social life, including kinship; collaborative partnerships in things like resource acquisition, childcare, and the division of labour; the “strength in numbers” often associated with social groups; people’s possession of useful information; and much more.

Some theorists speculate that ecological changes forced our ancestors into situations of greater interdependence, which initiated a set of positive feedback loops that gave rise to increasingly complex cooperation.

Second, there’s reciprocity (i.e., “you scratch my back, I scratch yours”). Humans trade favours, often in the context of relationships in which mutual trust and sympathy are built up over long periods. Such reciprocity depends on sophisticated cognitive capacities, including the ability to track individuals through time, remember their past behaviours, and delay gratification, which might explain why it’s rare in non-human animals.

In some cases, reciprocity exists entirely between two individuals. However, human social life also involves indirect reciprocity, in which actions are rewarded or punished by members of a community not directly affected by the act (“you scratch my back, someone else will scratch yours”). In this latter case, cooperation is typically scaffolded by social norms (that determine what constitutes cooperation), reputations (shared beliefs about how cooperative group members are), and gossip (socially transmitted information about people’s cooperative behaviour).

Third, there’s reputation-based partner choice. In environments in which individual success depends on cooperation, individuals will shop around for the best partners (e.g., mates, friends, and allies). Given this, it becomes crucial to cultivate a reputation as an attractive cooperator: that is, as someone capable of benefiting others (i.e., competent) and motivated to do so (i.e., trustworthy and benevolent).

This involves a kind of social selection in which individuals strive to out-compete rivals by attracting cooperation partners, and it likely played a powerful role in human evolution. Just as sexual selection (a form of social selection) gives rise to evolutionarily surprising traits like the peacock’s tail, the dynamics of partner choice can explain surprising features of our psychology, including intense desires to win social approval and an intuitive sense of fairness, which plausibly functions to secure a good reputation.

Finally, there’s competitive altruism. Human social worlds involve a distinctive kind of social status: prestige. Unlike dominance, the most common form of status in social animals, prestige is rooted in the ability to confer benefits on others rather than impose costs, and it elicits respect and admiration, not fear and avoidance. Once prestige hierarchies emerge, individuals can compete to win status through acts of altruism and generosity. This drive for prestige likely explains the most spectacular forms of self-sacrifice and heroism in our species. …

Consider interdependence. Although often depicted in heartwarming terms, it has a harsh logic. For example, people constantly (albeit often unconsciously) estimate the degree to which they have a stake in the interests of others, and emotions such as empathy closely track such estimations. For this reason, when you don’t depend on others or they threaten your interests, your empathy tends to disappear.

A similar lesson applies to reciprocity. By its very nature, reciprocity is selective. It involves helping others because helping - or the reputation for being helpful - will be repaid. In the absence of likely repayment, the motivation to cooperate therefore collapses.

For this reason, people are highly discriminating in which relationships they form and how much they help others. Of course, in social worlds organised around partner choice, it’s important not to appear too strategic and calculating. (Who wants to be friends with a stingy social climber?). The result is the evolution of a complex psychology with which people navigate these conflicting pressures, striving to avoid a reputation for being calculating and miserly whilst remaining sensitive to the costs of being indiscriminately friendly.

This choosiness extends to broader groups, which people join and leave in response to the benefits and costs they provide. In this sense, human communities function as coalitions that cooperate and coordinate in ways designed to promote shared interests. For this reason, an individual’s “ingroup” and the identity of their collaborators are constantly renegotiated, and communities often contain shifting sub-groups and alliances. To quote Raihani,

“The unromantic truth is that coalitions, friendships and alliances function as social tools that help us to achieve our goals (even if we don’t consciously think of them in this way).”

Finally, because much of human cooperation is rooted in reputation management and status competition, people are highly attentive to whether their behaviours and habits are socially rewarded, even when they vehemently deny this.

In fact, the very tendency to favour the “ingroup”, which Hare and Woods depict as a basic human motivation, seems to be rooted in reputation management. People treat their ingroup as a market of potential cooperation partners within which it’s important to make a good impression. Take away this reputational motive and ingroup favouritism mostly disappears.

Are you asexual?

I ran into this post and read almost none of it, but I read the first two paragraphs which are pretty interesting — and extracted below. And watched the TikTok video below. All very intriguing.

Gen Z is often described as a sexless generation. We are having less sex than previous generations did at the same age. We are less likely to have been on a date. More of us identify as asexual. In fact, according to this Stonewall report, more Gen Z Brits identify as asexual (5%) than gay (2%) or lesbian (3%).

All kinds of cultural and social influences could explain this. Early exposure and addiction to online porn might be one. I’ve written about risk-aversion and fear of rejection as another. Increased awareness of asexuality too. But there is also, I think, a medical explanation. More specifically: the widespread use of SSRIs and their sexual side-effects.

Maybe its all anti-depressants?

Russia isn’t an imminent threat, and Europe must rearm regardless

This was sent to me by a friend who despairs of my hawkishness on Ukraine. As he wrote “Something sensible on Ukraine I think - published in a reliable 'Putin must be defeated' newspaper”. I have some quibbles. I’d have downgraded what Putin says about his intentions and motives even more than the author did. And I wouldn’t be too confident in my conclusions about nuclear war. That’s not because I disagree with the author’s guessed calculations of the chances of nuclear war, but because nuclear war is so catastrophic.

Putin’s nuclear threats have been meant to deter the US and Nato from intervening directly in Ukraine. In terms of its own actions against Nato, however, the Russian government to date has been very cautious, despite the massive assistance Nato has given to Ukraine.

This is a ‘so far so good’ argument. Putin will be cautious until he’s not. We don’t know much more than that. Further, the piece is written on the presumption that expanding NATO was a terrible idea. If it triggered the Ukraine war it may have been. But NATO expansion to that point seems like rather a good idea. And why should those states abutting Russia, which are vanishingly unlikely to invade Russia, be kept forever vulnerable to Russian intimidation or even military adventurism? If it’s necessary to avoid nuclear war, well and good. Otherwise, why? Anyway, Europe should rearm and coordinate its defence capability and stop relying on Pax Americana. It should do so in any event, but particularly in light of it sliding into Chaos MAGAsterium.

The goal of European rearmament is laudable; the arguments being used to bring it about are not. As long as the war in Ukraine continues, there is a real risk that Nato and Russia will stumble into war as the result of some unintended clash. But the chances that this will come about as the result of a premeditated Russian invasion of a Nato country are minimal. … Russia has revealed itself to be a much weaker military power than was thought – and than Putin assumed – before the invasion. …

Given this dismal record, why would any Russian planner expect victory in an offensive against Nato? Even without the US, European countries combined heavily outweigh Russia in terms of numbers, weaponry and military spending (the greatest problem is the failure to pool these resources); and the Ukraine war has shown the great advantages currently enjoyed by the side that stands on the defensive. Moreover, in the event of an attack on a Nato country, western countries would certainly impose a complete and crippling naval blockade on Russian maritime energy exports. …

If European countries were confident in their ability to defend themselves without the US, they – or at least the French and Germans – could have summoned up the will to block the US push for Nato expansion, and made a real effort to reach compromise with Russia over Ukraine. This self-confidence would also allow Europe to extricate itself from embroilment in the growing confrontation between the US and China. Even more importantly, it would allow Europe to oppose disastrous US and Israeli policies in the Middle East, which threaten a return of terrorism and ethno-religious strife with Europe’s large and growing Muslim minorities.

Taylor

Obviously a hip newsletter like this one isn’t going to miss Taylor Swift. Our entire promotions division have been clamouring for me to cover it. Marketing and customer assurance agree.

But I resisted. If I’m not going to maintain standards, I can't expect all the underlings to maintain them. And where would we be without standards? (Well pretty much where we are now. But I digress!)

Then YouTube started sending me clips. That was because, at one of the high-end dinner parties I’m constantly attending, having sat next to someone who was heading to see Taylor at the G, I checked out the trending clips of her at the G on Twitter that night.

Anyway, I was astonished by the singing in this case. I don't know whether I've ever seen any other popstar sing as much in tune in a stadium. Then again, my son tells me it’s been post-produced. So perhaps it’s been retrospectively lip-synched. Who knows.

Heaviosity half-hour

Mind, Memory, Consciousness

A Middle English Phenomenology of the Soul

I loved this. It got me thinking about a bunch of things, but was also rather over my head. So you may not like it! It’s tricky to quote an extract from it and leave it intact, so if this passage piques your interest, feel free to click through and read it in situ. It’s unpacking the medieval text The Cloud of Unknowing

I quote the following passage from Joe Sachs’s translation [Of Aristotle’s On the Soul] too often, but its too succinct not to share in this context again, especially insofar as Sachs brings forth the interwoven character of the two modes.

In this context, Sachs discusses what he calls the “twofoldness” of discursive and contemplative thinking. In this image we find several noteworthy characteristics of noēsis and dianoia—that noēsis is thinking that considers things as “indivisible and whole” as opposed to dianoia, which thinks things in a linear fashion “step-by-step,” part by part. The contemplative thinking of noēsis, is more like a resting repose than than the active motion of dianoia. In this view, noēsis stands in relation to dianoia as its foundation, the means by which dianoia’s operations are framed and contextualized, offering sense and meaning to its ruminations. I quote Sachs in full in these points:

What is this intellect that is so difficult to locate? It is that which thinks things as indivisible and whole, as distinct from thinking them step-by-step in time, so that its thinking is more like rest than motion.

As with our children, so with our theories, and ultimately with all the work we do: our products become largely independent of their makers. We may gain more knowledge from our children or our theories than we ever imparted to them. This is how we can lift ourselves out of the morass of our ignorance.

This contemplative thinking (noēsis) of the intellect (nous) thus stands opposed to thinking things through (dianoia), but it also stands beneath the act of thinking things through and makes it possible. Every judgment is an external combination of a separated subject and predicate in our discursive thinking, but is simultaneously held together as a unity by the intellect. That is why Aristotle says that the contemplative intellect is that by means of which the soul thinks things through and understands. Its thinking is the foundation upon which all other thinking proceeds, just as having our feet on the ground is one of the conditions of our walking. Exclusively discursive thinking that could separate and combine, but could never contemplate anything whole, would be an empty algebra, a formalism that could not be applied to anything.

That last sentence speaks to the unmoored state of academic discourse, particularly, but far from exclusively in my own discipline of economics. “Exclusively discursive thinking that could separate and combine, but could never contemplate anything whole, would be an empty algebra, a formalism that could not be applied to anything”.

Quite.

Helmut Schmidt on Karl Popper

As Peter Singer wrote in 1974 in response to Bryan Magee’s suggestion that Popper had not received sufficient recognition:

The educated reader might think that Popper has received adequate recognition. After all, Popper … gained a world-wide reputation in 1945 with the publication of The Open Society and Its Enemies. Later, at the London School of Economics, he became Professor of Logic and Scientific method. He has now been a leading figure in the philosophy of science for many years; his Logic of Scientic Discovery, a translation of a work he had already published before he left Austria, must now be a part of almost every philosophy of science course in the English- speaking world.

In 1965 Popper became Sir Karl, and this year the Danish government chose him, at the age of seventy-one, for its Sonning Prize, previously awarded to figures like Bertrand Russell and Sir Winston Churchill, and worth around $45,000. … The rewards of academic life do not normally include knighthoods and large sums of money.

Anyway, I was reading this festschrift for Popper published in 1982. And I had to admire this appreciation by Helmut Schmidt.

In Plato's Republic, the ideal society is ruled by the philosopher-king. Since then, there has been a long tradition of utopian states in which the supposed contradiction of power and ideal spirit has been dissolved into a spiritualization of power or an enthronement of the spirit.

Such blueprints may have proved helpful in some respects. But at the same time they have reinforced the fundamental misconception that there is a scarcely reconcilable contradiction between spirit and power.

On the one hand, such approaches operate on the assumption that they possess ultimate insight into the true nature of things, based on the clear certainty of principles of reason. On the other hand, there lurks the raw desire for power that seeks its realization in unclean compromise and the dilution of pure principle. The result was only all too often that if the so-called spirit at some time came to power, it became omnipotent and actualized in a totalitarian and inhuman way its purportedly reasonable principles. Or power knocked in vain on the door of ideal spirit, because no one was willing to get involved in the mundane and burdensome business of actually transforming political ideals into the reality of state and society.

Karl Raimund Popper, whom we honor with this Festschrift, is one of the few people who have forthrightly tackled the horns of this dilemma. Like no one before, he has illustrated with brilliant acuity the defects of the utopian state in his critiques of Plato, Hegel, and Marx—who, on the basis of strict and supposedly absolute premises, attempted to predetermine the course of political development.

Popper, however, does more than criticize totalitarianism. As the title of his book, The Open Society and Its Enemies, already makes clear, Popper is a partisan of that form of government for which the separation of spirit and power is a deadly danger—that is, democracy.

Against the grand-principled and therefore presumably so moral blueprints for state and society of "utopian social engineering," Popper proposes "piecemeal social engineering"—a political approach not of pre-stamped, all-embracing prescriptions for the general welfare, not of fixation on the supposedly noble ultimate goals of human society, but of continuing involve-ment in the fight against actual and pressing evils.

This alternative has not been without its critics—especially among those who are convinced that there is a contradiction between spirit and power. What these critics overlook is that Popper's approach is no less moral, indeed of no lesser empathy, than the utopian solution. Popper's alternative is a fertile formula not for unprincipled wheeling and dealing, not for blind action devoid of goals and principles, but for a responsible and untiring struggle for a more just and peaceful reality.

For those who claim to possess ultimate truth, the world falls into two camps—friends and enemies. One must then limit the openness of society in order not to betray one's absolute principles. In a world of deep-reaching interdependence, this means that one has to win in order not to go under.

But since, in reality, only one who accepts improvement can ever improve others, every seeming victory in the friend/foe schema only brings about one's own undoing. Recent history has given as countless examples which show that such black-and-white, utopian thinking does not make peace more secure, but to the contrary increases disorder, and thereby makes war more likely.

Here then lies the justification for a political approach that overcomes conflict and is evolutionary. Its hope is to be found in the advice that Karl Popper gives at the end of his "Intellectual Autobiography" in the following way, not only to the world of science but to the world of political relations.

As with our children, so with our theories, and ultimately with all the work we do: our products become largely independent of their makers. We may gain more knowledge from our children or our theories than we ever imparted to them. This is how we can lift ourselves out of the morass of our ignorance.

The meaning of this for the politician is that we can, in small steps, day by day, move ever closer to the goal of a more just and peaceful world.

(Translated from German)