Hanging on the hinge of history

And other things I came across this week, including a special new segment on the upside of slavery

Hanging on the hinge of history

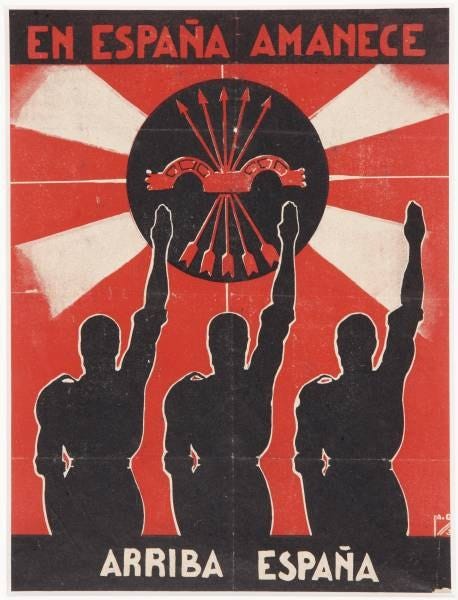

Remember the war against Franco

That’s a time to which each of us belongs

He may have won all the battles

But we had all the good songs.

Tom Lehrer’s “Folksong army”

Denis Glover asked if I’d be interested in sending an essay he’s just had published in Australian foreign affairs out to my mailing list and I was very pleased to do so and asked him to extract from what is a quite lengthy piece something more digestible as a taster. You can click through to a pdf of the whole essay.

On 24 July 1938, the Spanish Republic’s 5th and 15th Army Corps crossed the Ebro in an attempt to demonstrate to the democratic world, which had forsaken it, that after two years of fighting, the Spanish Republic was still alive, still capable of offensive operations, a black mark on the democratic world’s conscience which might still be erased. Around the world, supporters of the Spanish Republic held their breath. Maybe, they thought, Britain, France and America would finally end their policy of non-intervention and arm the Spanish democracy as a bulwark against fascism, allowing it to hang on until the now inevitable-looking European war broke out.

At first the offensive worked, liberating hundreds of square kilometres from fascist rule. But within a week the operation was revealed as the folly it always was. The Republican forces started with a severe disadvantage. Lacking sufficient trucks, artillery, tanks and aircraft, they were at the mercy of a highly mechanised and well-armed opposition, which had been supplied with the most up-to-date transport and weaponry by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. On the exposed rocky plains and hills of the open battleground, the Republican armies were pounded by plentiful and modern artillery and aircraft and confronted by fresh troops rushed to the front by thousands of American trucks supplied and fuelled on generous terms of credit by Ford, General Motors, Studebaker, Du Pont, Rio Tinto Zinc and the Texas Oil Company. Stubbornly and probably unwisely, thinking their Ebro attack a gallant example to the democratic world, the Republican troops hung on until 16 November, when they retreated back across the river to their old defensive positions. Their armies were now effectively destroyed. The final Nationalist offensive then commenced, leaving massacre in its wake. On 26 January Barcelona fell, followed two months later by Madrid and Valencia. On 1 April the war was over. The terms were unconditional surrender. The round-ups and executions accelerated. The concentration camps began to fill and would remain in operation until Francisco Franco, the last of the world’s 1930s fascist dictators, died in 1975. Six months after the Republic fell, World War II began.

How had this happened? It’s simple: fascist nations acted, democratic nations did nothing. As George Orwell, who fought for the Republican side, put it: “The outcome of the Spanish war was settled in London, Paris, Rome, Berlin – at any rate not in Spain . . . The Fascists won because they were the stronger; they had modern arms and the others hadn’t.”

Would the liberal-democratic nations of the world ever learn?

Sometimes, just sometimes, we do learn. In October 2022, the Ukrainian army broke out of its defensive positions and began its drive to recapture the city of Kherson on the banks of Dnipro River, near the Black Sea coast. It was a crucial moment in the war that had begun with a Russian invasion of Ukrainian territory eight months earlier. On 9 November, the Russian forces announced they were abandoning the city to fall back on a new defensive line on the eastern bank of the Dnipro. On 11 November the last of their troops left. Kherson had been liberated.

How had the outnumbered Ukrainian forces managed to pull off such a stunning reversal? Military experts are in general agreement on the two principal causes: the Ukrainians were united and better motivated, and the liberal democracies had armed them with superior weapons.

Were Orwell alive today, he may well have written that the outcome of this war is being decided in Washington, London, Berlin and Brussels as well as Ukraine. Seldom do we get such perfect laboratory conditions to compare the results of contrasting foreign policy decisions. The conclusion from this: the statesmen of the 1930s failed to arm democracy, stop fascism and prevent the slide into global war when they had the chance – the statesmen and women of today are succeeding. In the 1930s, America was isolationist, the European democracies non-interventionist, and the world unwilling to act. Today, the opposite is true, and democracy has the upper hand as a result.

The “Inner development goals'“ …

Nina Simone and Bach

Some 80 years ago, in a small North Carolina town, Eunice Waymon, a musically gifted, nine-year-old black girl, began taking piano lessons in the home of an exacting Englishwoman named Muriel Mazzanovich.

At first, young Eunice – the given name of jazz superstar Nina Simone – felt intimidated, recalling in her autobiography, I Put a Spell on You, that they “only played Bach and he seemed so complicated and different:”

In those first lessons, it seemed like the only thing she said was, “You must do it this way, Eunice. Bach would like it this way. Do it again.” And so I would.

As time went on I understood why Mrs. Mazzanovich only allowed me to practice Bach and soon I loved him as much as she did. He is technically perfect… Once I understood Bach’s music I never wanted to be anything other than a concert pianist. Bach made me dedicate my life to music.

Dark documentary

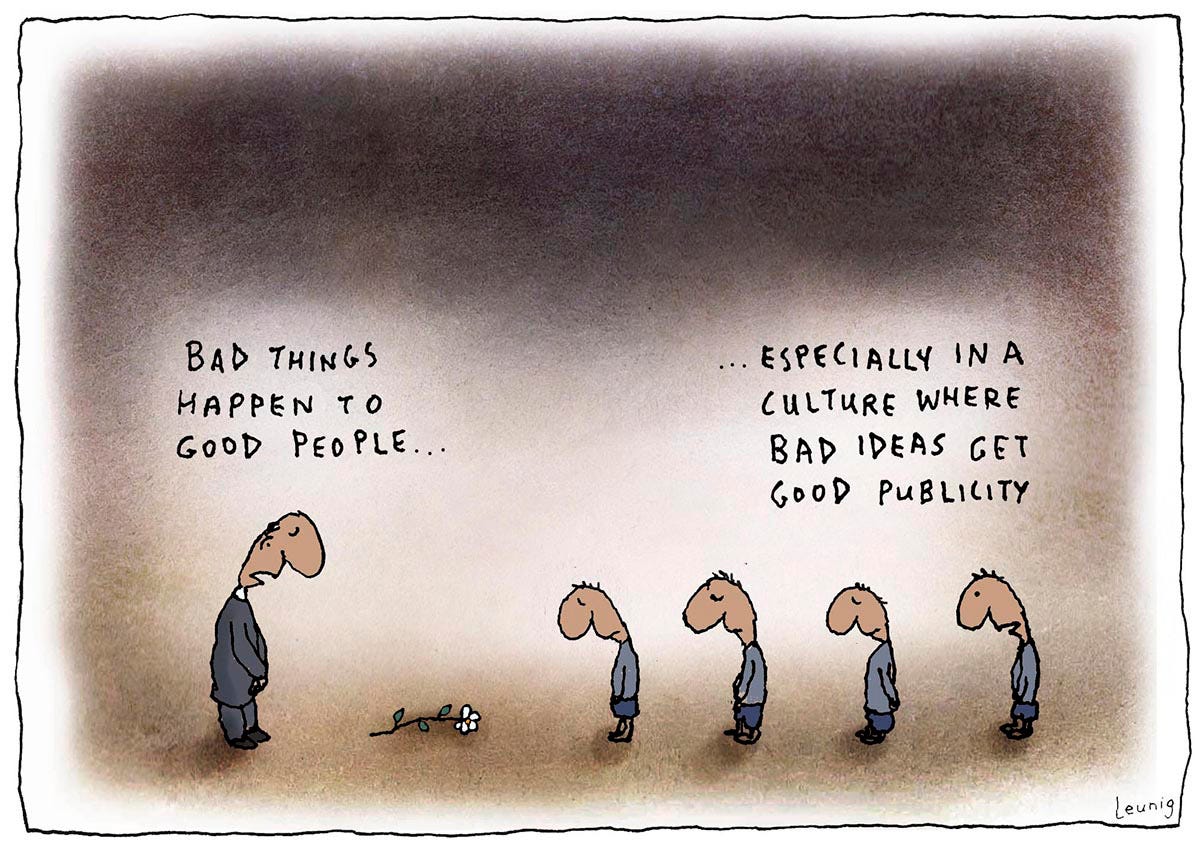

Against the white heat of culture war, all that is solid melts into air.

Coercion, care, hollowing out and airport security

There’s a lot of talk about the hollowing out of politics. Today one of the main reasons people join parties is if they want to work their way up to parliament or some other position. But a more general hollowing out process is going on as managers optimise and the managed respond as best they can.

Another way of looking at this is as the revival of Hobbes. I quote a small extract of an essay I wrote on the philosopher, neoliberal and friend of Friedrich Hayek who lost interest in Hayek’s Mont Pèlerin Society because of its perpetrating a kind of ‘inverse Marxism’.

Michael Polanyi and some other Mont Pèlerin Society liberals such as French political and social philosophers Bertrand de Jouvenel and Raymond Aron argued that the problems neoliberals were wrestling with had very deep roots. The central crisis of modernity was that both Marxism and laissez-faire sprang from the same reductionist conception of humanity. In private correspondence informing Hayek of his differences with him, Polanyi cited Jouvenel’s “wonderful” new book Sovereignty, which elaborated an alternative view of liberty they had been developing. As Jouvenel put it:

It is of capital importance to grasp the link between the authoritarian conclusions of Hobbes and the premises of an absolute libertarianism. Where each man acts as he wills and his will is made up for him by his desires, this liberty of his, if it is not to engender ‘the war of all against all’, can be kept in being only within the rigorous framework of laws strictly applied and exactly obeyed. This framework loses all solidity if the power grows feeble; … It looks as if the writings of Hobbes contain a serious lesson for our modern democracies. To the entire extent to which progress develops hedonism and moral relativism, to which individual liberty is conceived as the right of a man to obey his appetites, nothing but the strongest of powers can maintain society in being.

Anyway, on with the story:

I was recently in Stansted Airport, queueing in a low-ceilinged, quasi-temporary structure to enter the departure area for a Ryanair flight. There were two queues; the ‘priority queue’ which passengers had paid extra to join, and the ordinary one, but just one airport employee covering both, toggling stressfully between two irritated groups. Each time she switched, she left a line of people to wait. As I neared the front of the ordinary queue, she told a man with a wheelie case that he’d have to pay extra as his bag was too big. He objected and put it into the measuring frame. It fit easily, but the check-in woman refused to accept this, and demanded an extra £40. The man objected again and asked why the rules weren’t being followed, but ultimately paid up as he had no choice. He was clearly upset, but never raised his voice, used insulting or abusive language or made threatening gestures. He simply didn’t supply the meekness the very stressed out airport employee desired. As he moved into the boarding area, she called after him that she could have him taken off the plane, but it was very full and noisy, and he either ignored this or didn’t hear it and took a seat near the door. Both lines were now even longer, and she was dealing with the 200-odd passengers alone. …

I’m not surprised that a merely irritated and resistant passenger was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Her only agency in the situation, and the only acceptable reason to request help, was to cast the passenger as abusive or even dangerous. She couldn’t ask for help to do her actual job, difficult or near-impossible thought it was. It was designed to be that way. However, she could press an alarm button that brought security men almost immediately to deal with a situation wholly produced by her impossible working conditions.

The resources the airline and airport put into care, that is, providing the actual service they’d been paid for, were purposely minimal. The resources available for coercion, that is, the enforcement of compliance by the people ostensibly in receipt of the service, outweighed those for care by at least five to one, going on the number of security guards who turned up.

I was struck with Paul Graham’s discussion of ambition

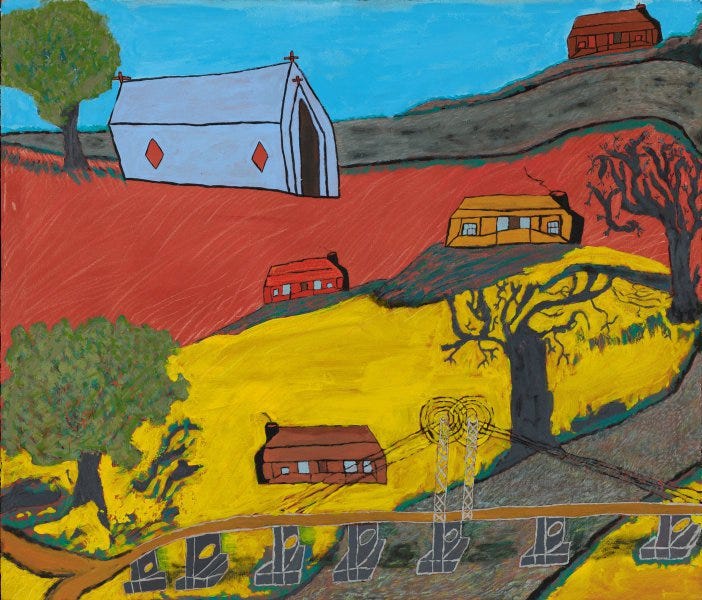

Roy Kennedy: whose art tells us about AI

I took a picture of this on my mobile on viewing this at the Art Gallery of NSW as there was a connection between someone I knew of and Roy Kennedy whose painting this is. It’s a lovely picture. In any event I was trying to find the Gallery’s webpage cataloguing it — which is here. I tried Bing Images which didn’t find it and Google Images which did. But here’s the thing. An incredibly high percentage of the images Bing did find were Australian aboriginal paintings, though of numerous different styles from the old Albert Namatjira style to the East Kimberley painting of folks like Rover Thomas. Amazeballs.

Google found it instantly and also turned up some interesting works and some lovely ones. But, as is often the case with AI, it was at its most interesting, most fertile when it was diverging from, rather than converging towards precisely what was asked of it.

‘The opposite of a solution in search of a problem’: Paul Graham on AI

In 2005, Graham cofounded Y Combinator, the wildly successful startup accelerator that’s helped Airbnb, Stripe, and other startups take off. He [tweeted], “A pattern I've noticed in the current YC batch: a large number of domain experts in all kinds of different fields have found ways to use AI to solve problems that people in their fields had long known about, but weren't quite able to solve. AI is turning out to be the missing piece in a large number of important, almost-completed puzzles.”

He shared no examples, but when a user replied that “the supply chain and procurement industry need this badly,” Graham responded, “I met two startups using AI for this just today.” OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, who in 2014 replaced Graham as president of Y Combinator, also weighed in on his venture’s unorthodox approach as a startup.

“OpenAI went against all of the YC advice,” he said during an onstage interview at an event hosted by fintech company Stripe in May. In addition to taking four and a half years to launch a product and being the most capital-intensive startup in Silicon Valley history, he said, “We were building a technology without any idea of who our customers were going to be or what they were going to use it for.”

Another lovely picture that turned up

Noah Smith thinks the typical [American] Millennial is thriving

It’s good to see more people being skeptical of the narrative that the Millennials are a uniquely screwed generation, doomed to be poorer than their parents by high housing prices and high student debt levels and the scars of the Great Recession. You still see some folks advancing this narrative, such as a recent story by Julian Mark in the Washington Post. But more and more folks are pushing back, especially from the progressive side. Here’s Dean Baker:

The Washington Post told readers that the current generation of young people is finding it much harder to become homeowners than young people did in the past. The data disagree with this claim…There is no doubt that the recent run-up in mortgage interest rates has made it much more difficult for first-time homebuyers, and if they stay anywhere near current levels we will likely see a drop in homeownership rates among the young. (The average for the first two quarters is already down slightly from the 2022 level.) However, the idea that the current generation of young people is finding it uniquely difficult to become homeowners simply is not true.

And here is Kevin Drum:

Millennials are doing fine. There's a small and vocal subset who are unhappy that they can't afford to live by themselves in a spacious apartment in Manhattan, but the vast majority are faring as well as previous generations and better than Millennials in any other country in the world. Someday a reporter from the Washington Post will read this and pass the news along to the rest of the country.

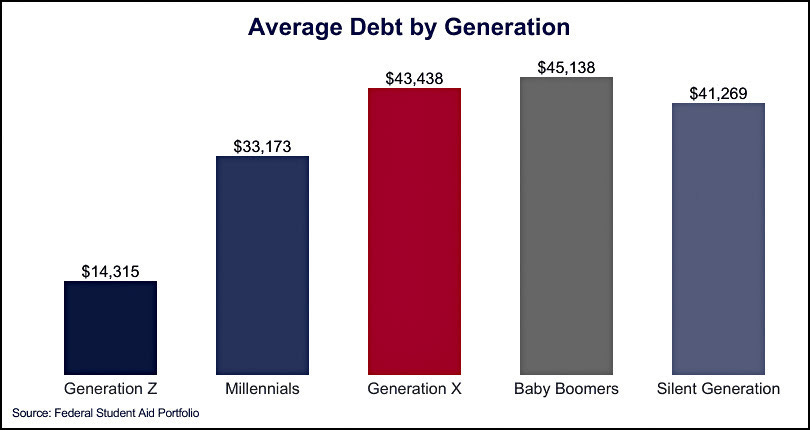

Here are a couple of great charts from Drum on homeownership rates and student debt levels:

Source: Kevin Drum

Source: Kevin Drum

For all the headwinds and disasters everyone talks about, Millennials are, economically speaking, a very average normal generation. I expect it to take at least a couple more years of economic success for this narrative to thoroughly replace the old one, though.

As a coda, one thing that irks me is that the way America’s housing system works makes it very easy to complain no matter what’s happening to housing prices and mortgage rates. If house prices are rising, you can complain about how hard it is for young people to afford a home. But if house prices are falling, you can complain about how middle-class wealth is being demolished (since most middle-class Americans have most of their wealth in their house). No matter what happens, you can tell a negative story about it. This is a product of the fact that America chose long ago to make real estate our main middle-class wealth vehicle, instead of stocks and bonds like they do in Japan. But in any case, I wish the people who complain about these things would imagine what their ideal situation for housing prices would look like.

A trip to the supermarket

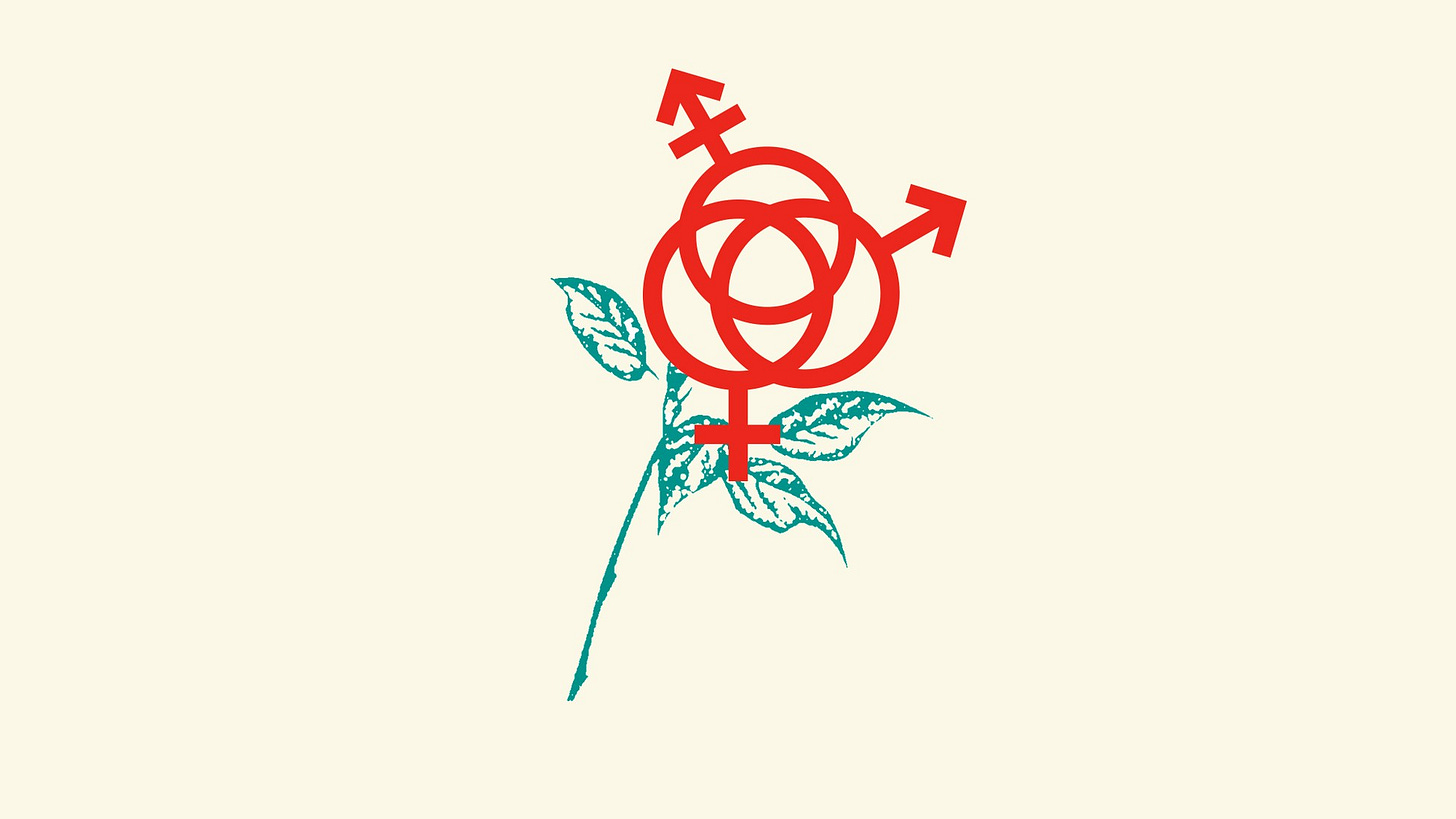

Trans nonsense over for now in the UK

Trans women are women (except in some unusual edge cases).

You wouldn’t think this would be so hard to accept, but the rules of activism dictate that you’ve got to get on people’s screens and to do that you scream betrayal and spout slogans. You also intimidate decision makers who go into ‘risk management’ mode and do what they can to remove any attack surfaces they might be displaying and to generally make the problem disappear.

Anyway, it’s a bit of a disaster for a politician because putting rapists into womens’ prisons on the basis of their self-identification is going to lose you a lot of votes. So Kier Starmer has quietly made sure that he doesn’t have that problem. From Helen Lewis in the Atlantic:

When keir starmer wanted to change the Labour Party’s stance on sex and gender, he didn’t give a set-piece speech or hold a press conference. Instead, the leader of Britain’s main opposition party stayed in the background, leaving Anneliese Dodds, a shadow minister with a low public profile, to announce the shift in a short opinion column in The Guardian. In just over 800 words, she made three big declarations. One was that “sex and gender are different.” Another was that, although Labour continues to believe in the right to change one’s legal gender, safeguards are needed to “protect women and girls from predators who might abuse the system.” Finally, Labour was therefore dropping its commitment to self-ID—the idea that a simple online declaration is enough to change someone’s legal gender for all purposes—and would retain the current requirement of a medical diagnosis of gender dysphoria.

From our friends at ‘The Upside of Slavery Project’

To comply with the Stop WOKE Act, a 2022 law championed by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis (R), the state needed to create a new curriculum for Black history. The law required the curriculum to "celebrate the inspirational stories of African Americans who prospered, even in the most difficult circumstances" and banned instruction that would make students "feel guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress because of actions, in which the individual played no part, committed in the past by other members of the same race."

Much of the criticism has centered around a provision of the new curriculum that requires instruction about "how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit." That provision was blasted by Black Republicans. “There is no silver lining in slavery,” Senator and presidential candidate Tim Scott (R-SC) said. “Slavery was really about separating families, about mutilating humans and even raping their wives. It was just devastating.” Congressmen Byron Donalds (R-FL) and John James (R-MI) also spoke out against the curriculum. DeSantis responded by attacking the three Black Republicans, claiming they accepted Democrats' "false narratives" and "lies."

DeSantis also defended the notion that enslaved people benefited from slavery. "Some of the folks…eventually parlayed, you know, being a blacksmith into doing things later in life," DeSantis told a reporter while campaigning in Iowa.

Speaking of slaves

Adam Smith understood why slave-owners never willingly emancipated their slaves?

Here’s Branko Milanovic on Adam Smith’s explanation for why slavery never dies a natural death, despite it’s being so inefficient and despite slave owners thinking they’re benefiting from slavery when they could benefit more from a ‘fairer’ kind of exploitation — like share cropping.

Smith very clearly in his Lectures on Jurisprudence states that slavery, as an economic institution is, inefficient. That means that a slave-toiled land would yield to the owner much less than if the same land were leased for a reasonable rent to the tenant. The reason is obvious: the tenant farmer has an incentive to increase production even if he has to give one-third (Smith’s estimate, but we can substitute any number) of the crop to the owner. The owner can easily calculate that over a period of x years, the Net Present Value (NPV) of the rent he gets would exceed the amount of the surplus product that he receives from slaves, to whom he pays only the subsistence wage. We are not talking here about high mathematics. Things are pretty simple. We can introduce different discount rates, and different amounts for rent, different productivity differentials for the land worked by free vs. slave labor etc., as Weingast does, but whatever set of (reasonable) assumptions we choose the final result is the same. The landlord should just dismiss his slaves, offer to some of them to continue working as free tenant-farmers, find new tenant famers if needed, and spend the rest of his time at leisure enjoying the rent.

So why did not slave owners do precisely that? Why we never observe in history endogenous scrapping of slave-holding when it is such an inefficient system and when the owners could actually make more money by hiring free labor than by using slaves?

It is a fair question and Weingast solves it by using a game theoretic framework showing that neither side can credibly commit to their part of the bargain. (He does this because he introduces, in my opinion, totally unnecessarily further assumption of slaves buying over time their freedom. Yes, slave owners can try to extract that too, but in a simple model, it is superfluous. For slave owners are better off even if they emancipate slaves for free.)

The reason why this spontaneous emancipation has never happened in the real world is the following. What would be the reaction that our emancipatory landlord would meet from his peers at the news that he has just released all his slaves? How would such an act be viewed by them? Certainly not with pleasure and warmth. As Smith writes, slave-owners like all property owners, the richer they are the more they live in fear of expropriation by the poor. Every slave-owner forms part of that implicit company. Everyone who, as a slave-owner, does not observe the compact is as much of a threat, if not more, to other slave-owners as slaves themselves.

Astonishing chess game by Australian Grandmaster David Smerdon

Why was Hayek recruited to the LSE, not Mises

Hint: Mises was too fond of fascism

In the first part of his review of Keynes’ Treatise on Money – signed ‘von’ from ‘Vienna’ – Hayek (1931, 270, 279–280) emphasized the quality difference between the British Neoclassical School and its better- informed ‘Continental’ equivalents. He perceptively noted that Keynes was in a ‘transitory phase in a process of rapid intellectual development’, yet he attributed this to intellectual immaturity:

so strongly does it bear the marks of the effect of the recent discovery of certain lines of thought hitherto unfamiliar to the school to which Mr. Keynes belongs, that it would be decidedly unfair to regard it as anything else but experimental.

Hayek provided an illustration from what he alleged was Keynes’ abuse of Knut Wicksell’s natural rate of interest analysis:

Mr. Keynes ignores completely the general theoretical basis of Wicksell’s theory. But, none the less, he seems to have felt that such a theoretical basis is wanting, and accordingly he has sat down to work one out for himself ... Would not Mr. Keynes have made his task easier if he had not only accepted one of the descendants of [Eugen] Böhm-Bawerk’s theory, but had also made himself acquainted with the substance of that theory itself?

In the second part of the review, ‘von’ Hayek (1932, 25) referred to the ‘unsatisfactory state of English theory of capital’; Hayek (1931, 271, n2) suggested to ill-read ‘English readers’ that his own Prices and Production (2012 [1931]) might narrow the educational gap between the two neoclassical branches.

Mises was equally haughty – but reached different conclusions. In ‘Social Liberalism’, Mises (2011 [1929], 70) asserted that

but a few dozen individuals all over the globe are cognizant of economics, and no statesman or politician cares about it...Politics does not dare introduce what the prevailing ideology is demanding. Taught by bitter experience, it subconsciously has lost confidence in the prevailing ideology. In this situation, no one, however, is giving thought to replacing the obviously useless ideology with a useful one. No help is expected from reason. Some are taking refuge in mysticism, others are setting their hopes on the coming of the ‘strong man’—the tyrant who will think for them and care for them.

Two years earlier – in the Austrian School version of Liberalism – Mises (1985 [1927], 51, 49) had been more specific. In contrast to Hayek’s alluring catchwords, ‘spontaneous’ order and ‘evolutionary rationalism’, Mises issued a blunt ‘eternal’ instruction:

It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aiming at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has, for the moment, saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history.

The ‘similar movements’ of ‘bloody counteraction’ that Mises was referring to included the French anti-Semitic Action Française plus ‘Germans and Italians’. ‘Italians’ obviously referred to Mussolini; Mises’ (1985 [1927], 44) reference to ‘Ludendorff and Hitler’ referred just as obviously to the 1923 Ludendorff–Hitler-Putsch.

The Austria Heimwehr (Home Guard), a private military organiza- tion similar to the Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel – Protective Front or Protection Squadron), split into an Austro-Fascist and a Nazi wing. In September 1933, the Austro-Fascist wing joined the new Vaterländische Front (Patriotic Front). Mises became member no. 282632 of the Patriotic Front on 1 March 1934 at the Austrian Chamber of Commerce (Kammer für Handel, Gewerte und Industrie) branch (Hülsmann 2007, 677, n149). The day after the Anschluss, several Chamber of Commerce ‘employees greeted each other with “Heil Hitler” ’ (Ebeling, no date, 67).

Mises (1985 [1927], 49–50), who apparently aspired to become the intellectual leader of a Fascist–Liberalism axis, declared that Liberals and Fascists were allies but differed in tactics:

What distinguished liberal from Fascist political tactics is not a difference of opinion regarding the use of armed force to resist armed attackers, but a difference in the fundamental estimation about the role of violence in a struggle for power.

Violence was the ‘highest principle’ and must lead to

civil war. The ultimate victor to emerge will be the faction strongest in number ... The decisive question, therefore always remains: How does one obtain a majority for one’s own party? This however is purely an intellectual matter.

Fascists would have to embrace Liberalism to achieve their common aims: if Fascism ‘wanted really to combat socialism it would oppose it with ideas’. Mises (1985 [1927], 50, 49, 51) would provide these ideas: ‘There is, however, only one idea that can be effectively opposed to socialism, viz, liberalism.’ Mises provided a justification based on histor- ical inevitability: ‘Fascism will never succeed as completely as Russian Bolshevism from freeing itself from the power of liberal ideas ... The next episode will be the victory of communism.’

As a form of White Terror (bloodthirsty, inter-Estate rivalry), Austrian ‘Liberty’ would be virtually unsaleable in countries that had progressed further away from neo-feudalism: Mises’ advocacy of fascism could have sabotaged Robbins’ Austrian outpost project.

Hayek (1992a [1963], 29–30) attempted to refocus the image:

Mises had broken away and deliberately stood apart as an intransi- gent...he had, however, already discovered kindred spirits in Edwin Cannan and Theodore Gregory at London and it is from this time in the early 1920s that the contacts between the Austrian and the London liberal groups date.

Mises’ ‘gradual building up of a new liberal doctrine’ required not the tactical embrace of Fascism but

a voyage of discovery to the 19th-century English literature since the current German literature would scarcely have enabled him to discover what the principles of liberalism really were.

Together with two LSE associates (co-founder Sidney Webb, and Professor of Economic History Richard Tawney), Harold Laski established a London office for the Frankfurt School (Institute for Social Sciences or Institute for Social Research). When Hitler came to power, the Jewish-born Herbert Marcuse escaped to the New York Institute of Social Research, where he published ‘The Struggle Against Liberalism in the Totalitarian View of the State’; Liberalism, Marcuse (1968 [1934], 3, 11–12), argued, was a front for the

total-authoritarian state...In order to get behind the usual camouflage and distortion and arrive at a true image of the liberalist economic and social system, it suffices to turn to Von Mises’ portrayal of liberalism.

Two years later, in The Rise of Liberalism the Philosophy of a Business Civilization, Laski (1936, 283) appeared to support this interpretation of Austrian Liberalism: ‘Fascism, in short, emerges as the institutional technique of capitalism in its phase of contraction.’ Although Mises was not specifically mentioned by Laski, Hayek (1978) explained that a rebuttal ‘became the program of [my] work for the next forty years’.9

When he died in 1950, some speculated that the 30 years before his death would be known as the ‘Age of Laski’ (Ebenstein 2003, 56). Laski had applied for Reform Club membership along with Hayek when the Club ‘badly needed members’; but had to withdraw his application because of the ‘outcry it caused’ (Burlingham and Billis 2005, 143, 215, 132; Woodbridge 1978, 86). Others at the Reform Club may have taken exception to Mises’ promotion of Fascism; in contrast, Hayek’s aristocratic ‘spontaneous’ order had a Reform Club lineage.

From: Robert Leeson, 2015. Hayek: A Collaborative Biography: Part II Austria, America and the Rise of Hitler, 1899–1933, Palgrave Macmillan

The marriage question

I’m about half way through this book and think it’s a masterpiece. On poking around a bit while I was following up some references in The German Genius I happened upon a translation of Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity and it turned out to be translated by one George Eliot. I wondered if it was that George Eliot and yes it was. She also translated Spinoza’s Ethics, but it gathered dust, unpublished for a century because (we learn in this book) her husband believed he’d been promised £75 for it and wouldn’t accept the £50 that was offered on presentation of the manuscript!

Be that as it may, The Marriage Question is a biography of sorts of Marian Evans who became George Eliot with the focus on the marriage question for her. It’s by Clare Carlisle, a philosopher of some note and in many ways it is in the spirit of Eliot’s writing — her “big head and heart and her wise wide views” to quote Barbara, an old friend who was the first to twig as to her identity on reading an extract of her first novel Adam Bede.

In any event, Eliot took up with George Lewes who was already married to a woman who was cohabiting with another man and having four of his children. So they could not marry legally. She nevertheless spoke of him as her husband. But that wasn’t enough to stop the torrent of disapproval in mid 19th-century England. This passage is from the book and documents the correspondence she received when she went with Lewes on a study tour to the continent.

Meanwhile literary London was pressing Chapman for information, and he wondered what he should say. Answering him, Marian became haughty in her own defence, her sentences shrinking to a crystalline formality that barely contains her fury:

I am sorry that you are annoyed with questions about me … About my own justification I am entirely indifferent … The phrase ‘run away’ as applied to me is simply amusing — I wonder what I had to run away from …

You ask me to tell you what reply I should give to inquiries. I have nothing to deny or conceal. I have done nothing with which any person has a right to interfere. I have surely full liberty to travel in Germany, and to travel with Mr Lewes. No one here seems to find it at all scandalous that we should be together … But I do not wish to take the ground of ignoring what is unconventional in my position. I have counted the cost of the step that I have taken and am prepared to bear, without irritation or bitterness, renunciation by all my friends. I am not mistaken in the person to whom I have attached myself. He is worthy of the sacrifice I have incurred, and my only anxiety is that he should be rightly judged.

Declaring herself ‘entirely indifferent’ to her own reputation, she fiercely defended Lewes. He was ‘in constant correspondence’ with his wife, she explained, and ‘nervously anxious’ about the welfare of his children. She had seen Lewes’s letters to Agnes, which confirmed that he had been honest with her about their marriage; she found his ‘conduct as a husband in the highest degree noble and self-sacrificing.’ Revealing that their future together had been undecided when they left England, she alluded to new ‘circumstances’, not involving her, that had made Lewes ‘determine on a separation’ from his wife. This probably meant that Agnes was pregnant by Thornton Hunt for a fourth time.

A week later she wrote a similar letter to Charles Bray, repeating this account of Lewes’s relations with Agnes and emphasizing his generosity towards his family. She closed with a stiff little paragraph about Cara Bray and Sara Hennell — to whom she had not yet written, though they had both written to her:

I am ignorant how far Cara and Sara may be acquainted with the state of things, and how they may feel towards me. I am quite prepared to accept the consequences of a step which I have deliberately taken and to accept them without irritation or bitterness. The most painful consequence will, I know, be the loss of friends. If I do not write, therefore, understand that it is because I desire not to obtrude myself.11

Her words were grown-up and perfectly articulated; her unwritten feelings were not so far from a child’s dread of withdrawn love. In fact, the sisters were more upset by her silence towards them than by her ‘running away’ with Lewes. Clever, empathic Cara had seen Marian rush into entanglements with several men, not all of them single. Having received enthusiastic letters about ‘Mr Lewes’ in recent months, she must have guessed they were now a couple. Yet she had responded to an inquiry from George Combe’s wife with a cool dismissal of rumours about her friend — ‘We have not heard of anything dreadful happening to Miss Evans,’12 she wrote to Mrs Combe; Marian had simply ‘travelled to Weimar under Mr Lewes’s escort’.

Sara answered Marian’s indirect question about ‘how they may feel towards me’ with a hurt, angry letter accusing her of ‘boasting’ about how serenely she could give up their friendship. This letter arrived in Weimar on the last day of October, and so consumed Marian that she wrote nothing in her journal that day. Her passionate reply to Sara bears no trace of the wary stoicism she had expressed to Charles Bray. Instead she explained how much she needed her friends:

When you say that I do not care about Cara’s or your opinion and friendship it seems much the same to me as if you said that I didn’t care to eat when I was hungry or to drink when I was thirsty. One of two things: either I am a creature without affection, on whom the memories of years have no hold, or, you, Cara and Mr Bray are the most cherished friends I have in the world … I wish to speak simply and to act simply but I think it can hardly be unintelligible to you that I shrink from writing elaborately about private feelings and circumstances. I have really felt it a privation that I have been unable to write to you about things not personal, in which I know you would feel a common interest, and it will brighten my thoughts very much to know that I may do so. Cara, you and my own sister are the three women who are tied to my heart by a cord which can never be broken and which really pulls me continually …

I have written miserably ill, and I fear all the while I am writing that I may be giving rise to some mistake. But interpret my whole letter so as to make it accord with this plain statement — I love Cara and you with unchanged and unchangeable affection, and while I retain your friendship I retain the best that life has given me next to that which is the deepest and gravest joy in all human experience.

Dumb questions can be fun

From Christopher Clark’s Revolutionary Spring, Europe Fighting for a New World, 1848-1849

Wherever they positioned themselves on the spectrum of political options, Europeans had to address and make sense of this current of change. In doing so, they embarked on long journeys, weaving mutable webs of ideas and commitments from the many chains of speculative thought unfolding across Europe in the 1830s and 1840s. It was the Saint-Simonians who inducted the socialist insurrectionary Martin Bernard into politics. He was not interested in the call to sexual equality that ‘bedazzled’ Suzanne Voilquin, but in the idea of ‘association’, a ‘deep word’, in which, for a time, he found his ‘compass’. But he later dropped the Saint-Simonians and studied Robespierre through the writings of Buonarroti. Felicité Lamennais began as a defender of the rights of the Church against Revolutionary and Napoleonic authoritarianism, but he later passed through a sequence of liberal commitments and ultimately fused what remained of his Christian spirituality with a form of socialist evangelism. He had started out as an opponent of the French Revolution and ended by affirming its value. At the core of these permutations was a preoccupation with the need to restore cohesion in a society that seemed to be fracturing into an infinity of alienated individuals.

We find the same flux in the writings of the Italian patriot in exile Giuseppe Mazzini. In 1832, Mazzini was still acclaiming the Jacobin phase of the French Revolution for heralding the programme of the ‘great social revolution’ that was supposedly on the horizon. But in 1833–4, his social radicalism waned, and he adopted a more volontarist and spiritualist conception of revolution, denouncing state terror and abjuring any profound mutation of the property base of society. When Karl Marx first immersed himself in the work of Hegel in 1837, it unleashed a revelatory shock akin to a religious conversion. ‘For some days’, he told his father in November 1837, his excitement made him ‘quite incapable of thinking’; he ‘ran about madly in the garden by the dirty water of the Spree’ and found himself overpowered by the desire to embrace every street corner loafer in Berlin. But Marx later abandoned the idealism of Hegel; in assembling his own materialist vision of history, he became one of the most voracious and brilliant consumers, assimilators and recombiners of other people’s ideas that the world has ever seen.

Even Donoso Cortés, later raised up as the very emblem of eloquent conservative intransigence in the Iberian mode, entered Spanish political life as an ambivalent liberal – his conversion to a more conservative stance came after the radical uprising at La Granja in August 1836. And the career of the Dutch liberal Johan Rudolf Thorbecke was marked by a journey in the other direction: he began adult life as a romantic conservative, hostile to constitutional experiments; the only legitimate source of law, he argued in an essay of 1824, was ‘the history of what [had] gone before’; any higher standard was ‘an illusion’. Yet, by the early 1840s, Thorbecke had metamorphosed into an advanced liberal and a partisan of radical constitutional reform who would play a key role in the transformations of 1848.

In an analysis of the political journalism of Alexis de Tocqueville, Roger Boesche noticed an incongruous pleating together of themes that seemed drawn from the ‘conservatism’ of Chateaubriand, the ‘liberalism’ of Constant and the ‘radical republicanism’ of Jules Michelet. Boesche interpreted this heterogeneity as an index of Tocqueville’s ‘unusual’ liberalism. But everyone was ‘unusual’ in the world of the 1830s and 1840s. These meandering intellectual journeys across the nineteenth century were not confined to the cultural elites. The philosopher Pierre-Simon Ballanche, an esoteric figure whose own thinking underwent numerous evolutions, reported in the 1830s that he had made the acquaintance of a foreman (maître ouvrier) who had gathered around him a small circle of fellow workers for philosophical discussions. ‘He had begun with Saint-Simonianism; he soon dropped that and began to profess the political economy of Fourier; but he quickly understood that a political economy founded on material well-being alone was insufficient; now he has begun to study my work and has been seized by a real enthusiasm for my doctrines…’

Everything and everyone was in motion. Perhaps this is always true. But there are periods whose signature is stabilization, when previously unstable formations cohere and coalesce and boundaries swim into sharper focus: the ‘Carolingian Renaissance’, the rise of territorial states in the 13th–14th centuries, the age of ‘confessionalization’, the ascendancy of the modern nation-state, the Cold War. And there are periods marked by flux and transition, where the direction of travel is harder to discern, when disparate forms of identity and commitment become unpredictably enmeshed with each other. Our own age is one. This, too, is part of the fascination of those decades.

Isaiah Berlin on he Apotheosis of the Romantic Will: The Revolt against the Myth of an Ideal World

I think Isaiah Berlin came to lunch with us at the farm one day — not that it made any difference to me. I was probably in my early 20s so old enough to have taken notice, but there you go. My mind (even more tiny then than today) was on other things. Anyway I came upon this essay of his in a second hand book sitting in my bookshelf — which I picked up because I’d just been listening to The German Genius. It’s a good essay, even if lots of the quoted sources are unknown to me.

This is the last part of it. If the first few paragraphs don’t grab you, I won't be surprised, but, with each paragraph building on the one before, it was hard to extract less. Anyway, skim it if necessary but read the final three paragraphs beginning “Neither Hoffmann nor Tieck sets out, any more than Pascal or Kierkegaard or Nerval, to deny the truths of science” which I’ve bolded for you.

Fichte drives this still further. Inspired both by Kant and less obviously by Herder, an admirer of the French Revolution, but disillusioned by the Terror, humiliated by the misfortunes of Germany, speaking in defence of ‘reason’ and ‘harmony’ – words used by now in more and more attenuated and elusive senses – Fichte is the true father of Romanticism, above all in his celebration of will over calm, discursive thought. A man is made conscious of being what he is – of himself as against others or the external world – not by thought or contemplation, since the purer this is, the more a man’s thought is in its object, the less conscious of itself it will be as a subject; self-awareness springs from encountering resistance. It is the impact on me of what is external to me, and the effort to resist it, that makes me know that I am what I am, aware of my aims, my nature, my essence, as opposed to what is not mine; and since I am not alone in the world, but connected by myriad strands, as Burke has taught us, to other men, it is this impact that makes me understand what my culture, my nation, my language, my historical tradition, my true home, have been and are. I carve out of external nature what I need, I see it in terms of my needs, temperament, questions, aspirations: ‘I do not accept what nature offers because I must,’ Fichte declares, ‘I believe it because I will.’

Descartes and Locke are evidently mistaken – the mind is not a wax tablet upon which nature imprints what she pleases, it is not an object, but a perpetual activity which shapes its world to respond to its ethical demands. It is the need to act that generates consciousness of the actual world: ‘We do not act because we know, but we know because we are called upon to act.’ A change in my notion of what should be will change my world. The world of the poet (this is not Fichte’s language) is different from the world of the banker, the world of the rich is not the world of the poor; the world of the Fascist is not the world of the liberal, the world of those who think and speak in German is not the world of the French. Fichte goes further: values, principles, moral and political goals, are not objectively given, not imposed on the agent by nature or a transcendent God. I am not determined by ends: ends are determined by me. Food does not create hunger, it is my hunger that makes it food. This is new and revolutionary.

Fichte’s concept of the self is not wholly clear: it cannot be the empirical self, which is subject to the causal necessitation of the material world, but an eternal, divine spirit outside time and space, of which empirical selves are but transient emanations; at other times Fichte seems to speak of it as a super-personal self in which I am but an element – the Group – a culture, a nation, a Church. These are the beginnings of political anthropomorphism, the transformation of State, nation, progress, history, into super-sensible agents, with whose unbounded will I must identify my own finite desires if I am to understand myself and my significance, and be what, at my best, I could and should be. I can understand this only by action: ‘Man shall be and do something’, we must be a ‘quickening source of life’, not an ‘echo’ of it or an ‘annex’ to it. The essence of man is freedom, and although there is talk of reason, harmony, the reconciliation of one man’s purpose to that of another in a rationally organised society, yet freedom is a sublime but dangerous gift: ‘Not nature but freedom itself produces the greatest and most terrible disorders of our race – man is the cruellest enemy of man.’ Freedom is a double-edged weapon; it is because they are free that savages devour each other. Civilised nations are free, free to live in peace, but no less free to fight and make war; culture is not a deterrent of violence but its tool. He advocates peace, but if it is to be a choice between freedom, with its potentiality of violence, or the peace of subjection to the forces of nature, he unequivocally prefers – and indeed thinks it is the essence of man not to be able to avoid preferring – freedom. Creation is of man’s essence; hence the doctrine of the dignity of labour, of which Fichte is virtually the author – labour is the impressing of my creative personality upon the material brought into existence by this very need, it is a means for expressing my inner self. The conquest of nature and the attainment of freedom for nations and cultures is the self-realisation of the will: ‘Sublime and living will! Named by no name, compassed by no thought!’1

Fichte’s will is dynamic reason, reason in action. Yet it was not reason that seems to have impressed itself upon the imagination of his listeners in the lecture-halls of Jena and Berlin, but dynamism, self-assertion; the sacred vocation of man is to transform himself and his world by his indomitable will. This is something novel and audacious: ends are not, as had been thought for more than two millennia, objective values, discoverable within man or in a transcendent realm by some special faculty. Ends are not discovered at all, but made, not found but created. The Russian writer Alexander Herzen asked later in the nineteenth century: Where is the dance before I have danced it? Where is the picture before I have painted it? Where indeed? Joshua Reynolds thought that it dwelt in some super-sensuous empyrean of eternal Platonic forms which the inspired artist must discern and labour to embody as best he can in the medium in which he works – pigment, or marble, or bronze. But the answer Herzen implies is that before the work of art is created it is nowhere, that creation is creation out of nothing – an aesthetics of pure creation which Fichte applies to the realm of ethics, of all action. Man is not a mere compounder of pre-existent elements; imagination is not memory, it literally generates, as God generated the world. There are no objective rules, only what we make.

Art is not a mirror held up to nature, the creation of an object according to the rules, say, of harmony or perspective, designed to give pleasure. It is, as Herder taught, a means of communication, of self-expression for the individual spirit. What matters is the quality of this act, its authenticity. Since I, the creator, cannot control the empirical consequences of what I do, they are not part of me, do not form part of my real world. I can control only my own motives, my goals, my attitude to men and things. If another man causes me damage, I may suffer physical pain, but I shall not suffer grief unless I respect him, and that is within my control. Man is the inhabitant of two worlds, said Fichte, one of which, the physical, I can afford to ignore; the other, the spiritual, is in my power. That is why worldly failure is unimportant, why worldly goods – riches, security, success, fame – are trivial in contrast with what alone counts, my respect for myself as a free being, my moral principles, my artistic or human goals; to give up the latter for the former is to compromise my honour and independence, my real life, for the sake of something outside it, part of the empirical-causal treadmill, and this is to falsify what I know to be the truth, to prostitute myself, to sell out – for Fichte and those who followed him the ultimate sin.

From here it is no great distance to the worlds of Byron’s gloomy heroes – satanic outcasts, proud, indomitable, sinister – Manfred, Beppo, Conrad, Lara, Cain – who defy society and suffer and destroy. They may, by the standards of the world, be accounted criminal, enemies of mankind, damned souls: but they are free; they have not bowed the knee in the House of Rimmon; they have preserved their integrity at a vast cost in agony and hatred. The Byronism that swept Europe, like the cult of Goethe’s Werther half a century earlier, was a form of protest against real or imaginary suffocation in a mean, venal and hypocritical milieu, given over to greed, corruption and stupidity. Authenticity is all: ‘The great object in life’, Byron once said, ‘is Sensation – to feel that we exist – even though in pain.’1 His heroes are like Fichte’s dramatisation of himself, lonely thinkers: ‘There was in him a vital scorn of all: […] He stood a stranger in this breathing world.’ The attack on everything that hems in and cramps, that persuades us that we are part of some great machine from which it is impossible to break out, since it is a mere illusion to believe that we can leave the prison – that is the common note of the Romantic revolt. When Blake says ‘A Robin Red breast in a Cage / Puts all Heaven in a Rage’, the cage is the Newtonian system. Locke and Newton are devils; ‘Reasoning’ is ‘secret Murder’; ‘Art is the Tree of Life […] Science is the Tree of Death’. ‘The tree of knowledge has robbed us of the fruit of life’, said Hamann a generation earlier, and this is literally echoed by Byron. Freedom involves breaking rules, perhaps even committing crimes. This note was earlier sounded by Diderot (and perhaps by Milton in his conception of Satan, and in Shakespeare’s Troilus). Diderot conceived of man as the theatre of an unceasing civil war between an inner being, the natural man, struggling to get out of the outer man, the product of civilisation and convention. He drew analogies between the criminal and the genius, solitary and savage beings who break rules and defy conventions and take fearful risks, unlike the hommes d’esprit who scatter their wit elegantly and agreeably, but are tame and lack the sacred fire. Half a century before Byron, Lenz, the most authentic voice of the Sturm und Drang, wrote: ‘Action, action is the soul of the world, not pleasure […]. Without action all pleasure, feeling, knowledge are nothing but postponed death. […] Clear a space! God brooded over the void and a world arose. Destroy! Something will arise! Oh God-like feeling!’1 What matters is the intensity of the creative impulse, the depth of nature from which it springs, the sincerity of one’s beliefs, readiness to live and die for a principle, which counts for more than the validity of the conviction or the principle itself. Voltaire and Carlyle both wrote about Muhammad. Voltaire’s play is simply an attack on obscurantism, intolerance, religious fanaticism; when he speaks of Muhammad as a blind and destructive barbarian, he means, as everyone knew, the Roman Church, for him the greatest obstacle to justice, happiness, freedom, reason – universal goals which satisfy the deepest demands of all men at all times. When, a century later, Carlyle deals with the same subject, he cares only about Muhammad’s character, the stuff of which he is made, and not his doctrines or their consequences: he calls him ‘a fiery mass of life cast up from the great bosom of nature herself’, possessed of ‘a deep, great, genuine sincerity’.2 In Herder’s words: ‘Heart! Warmth! Blood! Humanity! Life!’ The attack on Voltaire and the ‘second-hand’4 shallow talk in France was mounted by the Germans in the last third of the eighteenth century. Half a century later the goal of rational happiness, especially in its Benthamite version, is rejected contemptuously by the new, Romantic generation in continental Europe, for whom pleasure is but ‘tepid water on the tongue’; the phrase is Hölderlin’s,1 but it could just as well have been uttered by Musset or Lermontov. Goethe, Wordsworth, Coleridge and even Schiller made their peace with the established order. So, in due course, did Schelling and Tieck, Friedrich Schlegel and Arnim and a good many other radicals. But in their earlier years these men celebrated the power of the will to freedom, to creative self-expression, with fateful consequences for the history and outlook of the years that followed.

One form of these ideas was the new image of the artist, raised above other men not only by his genius but by his heroic readiness to live and die for the sacred vision within him. It was this same ideal that animated and transformed the concept of nations or classes or minorities in their struggles for freedom at whatever cost. It took a more sinister form in the worship of the leader, the creator of a new social order as a work of art, who moulds men as the composer moulds sounds and the painter colours – men too feeble to rise by their own force of will. An exceptional being, the hero and genius to whom Carlyle and Fichte paid homage, can lift others to a level beyond any which they could have reached by their own efforts, even if this can be achieved only at the cost of the torment or death of multitudes.

For more than two millennia the view prevailed in Europe that there existed an unalterable structure of reality, and the great men were those who understood it correctly either in their theory or their practice – the wise who knew the truth, or the men of action, rulers and conquerors, who knew how to achieve their goals. In a sense the criterion of greatness was success based on getting the answer right. But in the age of which I speak the hero is no longer the discoverer, or the winner in the race, but the creator, even, or perhaps all the more, if he was destroyed by the flame within him – a secularised image of the saint and martyr, of the life of sacrifice. For in the life of the spirit there were no objective principles or values – they were made so by a resolve of the will which shaped a man’s or a people’s world and its norms; action determined thought, not vice versa. To know is to impose a system, not to register passively, said Fichte; and laws are drawn not from facts, but from our own self. One categorises reality as the will dictates. If the empirical facts prove recalcitrant, one must put them in their place, in the mechanical treadmill of causes and effects, which have no relevance to the life of the spirit – to morality, religion, art, philosophy, the realm of ends, not means.

For these thinkers ordinary life, the common notion of reality, and in particular the artificial constructions of the natural sciences and practical techniques – economic, political, sociological – no less than that of common sense, are a baseless, utilitarian fabrication, what Georges Sorel later called ‘la petite science’, something invented for their own convenience by technologists and ordinary men, not reality itself. For Friedrich Schlegel and Novalis, for Wackenroder and Tieck and Chamisso, above all for E. T. A. Hoffmann, the tidy regularities of daily life are but a curtain to conceal the terrifying spectacle of true reality, which has no structure, but is a wild whirlpool, a perpetual tourbillon of the creative spirit which no system can capture: life and motion cannot be represented by immobile, lifeless concepts, nor the infinite and unbounded by the finite and the fixed. A finished work of art, a systematic treatise, are attempts to freeze the flowing stream of life; only fragments, intimations, broken glimpses can begin to convey the perpetual movement of reality. The prophet of Sturm und Drang, Hamann, had said that the practical man was a somnambulist, secure and successful because he was blind; if he could see, he would go mad, for nature is a wild dance, and the irregulars of life – outlaws, beggars, vagabonds, the visionary, the sick, the abnormal – are closer to it than French philosophers, officials, scientists, sensible men, pillars of the enlightened bureaucracy: ‘The tree of knowledge has robbed us of the fruit of life.’ The early German Romantic plays and novels are inspired by an attempt to expose the concept of a stable, intelligible structure of reality which calm observers describe, classify, dissect, predict, as a sham and a delusion, a mere curtain of appearances designed to protect those not sensitive or brave enough to face the truth from the terrifying chaos beneath the false order of bourgeois existence. The irony of the cosmos plays with us all, wrote Tieck: ‘everything visible is hung about us like tapestries with shimmering colours and patterns’; beyond the tapestries is ‘a region of dreams and delirium; none dares […] lift the hangings and peer beyond the screens’.

Tieck is the originator of the Novel and the Theatre of the Absurd. In William Lovell everything turns out to be its opposite: the personal turns out to be impersonal; the living is discovered to be the dead; the organic, the mechanical; the real, the artificial; men seek freedom and fall into the blackest slavery. In Tieck’s plays there is a deliberate attempt to confound the imaginary and the real: characters in the play (or in a play within the play) criticise the play, complain about the plot, and about the equipment of the theatre; members of the audience expostulate and demand that the illusion, on which all drama rests, be preserved; they are in turn answered sharply by the play’s characters from the stage, to the bewilderment of the real audience; at times musical keys and dynamic tempi engage in dialogues with each other. In Prince Zerbino, when the Prince despairs of reaching the end of his journey he orders the play to be turned backwards – the events to be replayed in reverse order, to unhappen – the will is free to order what it pleases. In one of Arnim’s plays an old nobleman complains that his legs are growing longer and longer: this is the result of boredom; the old man’s inner state is externalised; moreover, his boredom itself is a symbol of the death-throes of the old Germany. As a perceptive contemporary Russian critic has remarked, this is full-blown expressionism long before its triumph a century later, in the Weimar period.

The attack upon the world of appearances at times takes surrealist forms: in one of Arnim’s novels the hero finds that he has wandered into a beautiful lady’s dreams, is invited by her to sit in one of her chairs, wishes to escape from the dream that is not his, sees that the chair remains empty, and feels great relief. Hoffmann carried this war upon the objective world, upon the very notion of objectivity, to its outer limits: old women who turn into brass door-knockers, or State councillors who step into brandy glasses, are dissipated into alcoholic fumes, float over the earth, then recoagulate themselves and return to their armchairs and dressing-gowns – these are not innocent flights of fancy but spring from a deranged imagination in which the will is uncontrolled and the real world proves to be a phantasmagoria. After this, the way lies clear for Schopenhauer’s world tossed hither and thither by a blind, aimless, cosmic will, for Dostoevsky’s underground man, and Kafka’s lucid nightmares, for Nietzsche’s evocation of the Kraftmenschen condemned in Plato’s dialogues – Thrasymachus, or Callicles – who see no reason against sweeping aside the cobwebs of laws and conventions if they obstruct their will to power, for Baudelaire’s ‘enivrez-vous sans cesse!’; let the will become intoxicated by drugs or pain, dreams or sorrow, no matter by what, but let it break its chains.

Neither Hoffmann nor Tieck sets out, any more than Pascal or Kierkegaard or Nerval, to deny the truths of science, or even those of common sense, at their own level – that is, as categories required for limited purposes, medical or technological or commercial. This was not the world which mattered; they conceived true reality as distinct from the irrelevant surface of things. The world without frontiers or barriers, within or without, shaped and expressed by art, by religion, by metaphysical insight, by all that is involved in personal relationships – this was the world in which the will is supreme, in which absolute values clashed in irreconcilable conflict, the ‘nocturnal world’ of the soul, the source of all imaginative experience, all poetry, all understanding, all that men truly live by. It is when scientifically minded rationalists claimed to be able to explain and control this level of experience in terms of their concepts and categories, and declared that conflict and tragedy arose only from ignorance of fact, inadequacies of method, the incompetence or ill will of rulers and the benighted condition of their subjects, so that in principle, at least, all this could be put right, a harmonious, rationally organised society established, and the dark sides of life made to recede like an old, insubstantial, scarcely remembered nightmare – it is then that the poets and the mystics and all those who are sensitive to the individual, unorganisable, untranslatable aspects of human experience tended to rebel. Such men react against what appears to them to be the maddening dogmatism and smooth bon sens of the raisonneurs of the Enlightenment and their modern successors. Nor, despite the brilliant and heroic efforts of both Hegel and Marx to integrate the tensions, paradoxes and conflicts of human life and thought into new syntheses of successive crises and resolutions – the dialectic of history or cunning of reason (or of the process of production), leading to an ultimate triumph of reason and realisation of human potentialities – have the terrible doubts injected by these indignant critics ever been stilled.

I do not mean that these doubts have in fact prevailed, at least in the realm of ideology. Even if belief in the happy innocence of our first ancestors – Saturnia regna – has largely waned, faith in the possibility of a golden age still to come has remained unimpaired, and indeed spread far beyond the Western world. Both liberals and socialists, and many who put their trust in rational and scientific methods designed to effect a fundamental social transformation, whether by violent or gradual methods, have held this optimistic belief with mounting intensity during the last hundred years. The conviction that once the last obstacles – ignorance and irrationality, alienation and exploitation, and their individual and social roots – have been eliminated, true human history, that is, universal harmonious co-operation, will at last begin is a secular form of what is evidently a permanent need of mankind. But if it is the case that not all ultimate human ends are necessarily compatible, there may be no escape from choices governed by no overriding principle, some among them painful, both to the agent and to others. From this it would follow that the creation of a social structure that would, at the least, avoid morally intolerable alternatives, and at the most promote active solidarity in the pursuit of common objectives, may be the best that human beings can be expected to achieve, if too many varieties of positive action are not to be repressed, too many equally valid human goals are not to be frustrated. But a course demanding so much skill and practical intelligence – the hope of what would be no more than a better world, dependent on the maintenance of what is bound to be an unstable equilibrium in need of constant attention and repair – is evidently not inspiring enough for most men, who crave a bold, universal, once-and-for-all panacea. It may be that men cannot face too much reality, or an open future, without a guarantee of a happy ending – providence, the self-realising spirit, the invisible hand, the cunning of reason or of history, or of a productive and creative social class. This seems borne out by the social and political doctrines that have proved most influential in recent times. Yet the Romantic attack on the system-builders – the authors of the great historical libretti – has not been wholly ineffective. Whatever the political theorists may have taught, the imaginative literature of the nineteenth century, and of ours too, which expresses the moral outlook, conscious and unconscious, of the age, has (despite the apocalyptic moments of Dostoevsky or Walt Whitman) remained singularly unaffected by Utopian dreams. There is no vision of final perfection in Tolstoy, or Turgenev, in Balzac or Flaubert or Baudelaire or Carducci. Manzoni is perhaps the last major writer who still lives in the afterglow of a Christian-liberal, optimistic eschatology. The German Romantic school and those it influenced, directly and indirectly – Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Wagner, Ibsen, Joyce, Kafka, Beckett, the existentialists – whatever fantasies of their own they may have generated, do not cling to the myth of an ideal world. Nor from his wholly different standpoint does Freud. Small wonder that they have all been duly written off as decadent reactionaries by Marxist critics. Some indeed, and those not the least gifted or perceptive, are justly so described. Others were, and are, the very opposite: humane, generous, life-enhancing, openers of new doors.

One is not committed to applauding or even condoning the extravagances of Romantic irrationalism if one concedes that, by revealing that the ends of men are many, often unpredictable, and some among them incompatible with one another, the Romantics have dealt a fatal blow to the proposition that, all appearances to the contrary, a definite solution of the jigsaw puzzle is, at least in principle, possible, that power in the service of reason can achieve it, that rational organisation can bring about the perfect union of such values and counter-values as individual liberty and social equality, spontaneous self-expression and organised, socially directed efficiency, perfect knowledge and perfect happiness, the claims of personal life and the claims of parties, classes, nations, the public interest. If some ends recognised as fully human are at the same time ultimate and mutually incompatible, then the idea of a golden age, a perfect society compounded of a synthesis of all the correct solutions to all the central problems of human life, is shown to be incoherent in principle. This is the service rendered by Romanticism, and in particular by the doctrine that forms its heart, namely, that morality is moulded by the will and that ends are created, not discovered. When this movement is justly condemned for the monstrous fallacy that life is, or can be made, a work of art, that the aesthetic model applies to politics, that the political leader is, at his highest, a sublime artist who shapes men according to his creative design – a fallacy that leads to dangerous nonsense in theory and savage brutality in practice – this at least may be set to its credit: that it has permanently shaken the faith in universal, objective truth in matters of conduct, in the possibility of a perfect and harmonious society, wholly free from conflict or injustice or oppression – a goal for which no sacrifice can be too great if men are ever to create Condorcet’s reign of ‘truth, happiness and virtue’, bound ‘by an indissoluble chain’; an ideal for which more human beings have, in our time, sacrificed themselves and others than, perhaps, for any other cause in human history.