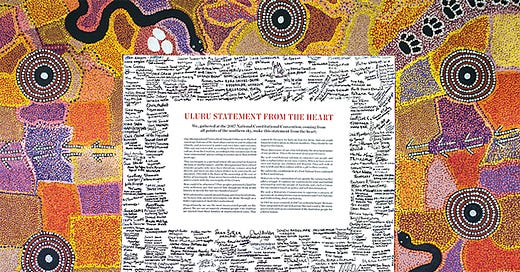

Government by amnesia: a new Voice

Charles Wylie is a friend of mine — whom I know through my son. Of all the young people I know, he’s the one who’s most put himself ‘in play’ as it were. He didn’t go into corporate life, or academia, or government or human rights or ‘social innovation’ #NTTAWT. He went teaching in Tennant Creek.

That’s meant that he’s been making a contribution. First through his teaching and now by trying to reflect on what he’s witnessed. (Which, in discussions with me he’s said is far more dysfunctional and forlorn than the fairly dismal situation he expected to encounter.)

Charles is upset at the failure of our political class to — you know — actually engage with the problem they claim to be trying to solve. He’s discovered what I call government by amnesia. As he argues, the Voice was a rebranding and constitutionalising of something that’s been around twice, and failed twice.

Putting in my own oar, I think a more circumspect way of putting it would be to say that a consultative voice has been an important part of failure. In each case there was plenty more to the failure than that. I think we undoubtedly need to more fully engage indigenous people in building their future. And given that we’ve been trying to do that since the Whitlam years, you’d think the discussion of The Voice might have got onto what has worked in the past, what hasn’t, what we’ve learned, what we need to learn and so on.

But if you thought that, you’d be wrong.

I don’t really blame anyone very much. It is easy to blame the indigenous leadership and their allies (as they now like to be called). And it’s easy to blame their opponents. But you have to remember, both those for and against the Voice were trying to achieve a political outcome. And if that’s what you’re trying to do you’re almost exclusively engaged in a propaganda war. This is the outcome that has co-evolved from around 200 years of Darwinian evolution as political operatives have tried to win elections, the media have tried to optimise profit and clicks and voters have watched on as others try to manipulate them. In this system, whatever side you’re on, trying to learn from your own mistakes doesn’t make good propaganda.

So you don’t’ do it.

Here’s Charles’ first Substack.

Beyond serving as a therapeutic device for alleviating the guilt of educated Australians, the Voice is propelled by its claim to be the solution to the enduring problem of Indigenous Disadvantage. … This talking point was my lived reality. Until recently I spent several years living and working in the remote town of Tennant Creek, infamous for its position at the frontline of Indigenous Disadvantage. I was able to witness the profound dysfunction which defines remote community life, and the way in which the government and its myriad services fail to ameliorate this dysfunction, and often even enable it. It is safe to say that I am still grappling with my experience.

Indigenous Disadvantage as a talking point is notable for two things. Firstly, it is notable for how little familiarity the Australian public has with it. Most Australians have never seen the reality of life in a community or town camp. As a result, Indigenous Disadvantage is poorly understood, and exists in the public consciousness as an abstract problem which occurs far away in the desolate expanses of the Australian outback.

Second …Indigenous Disadvantage has defied everything thrown at it. It has seen off decades-long attempts by successive Australian Governments to fix it; it has swallowed the many tens of billions of dollars thrown its way; it has spawned the erection of an Aboriginal affairs industrial-complex which cannot eradicate it; it has thwarted the self-determination movement; it has mocked the Closing the Gap targets. This crystallises the paradox of Indigenous Disadvantage: for all the colossal amount of effort, programs, and money the government expends on improving Indigenous outcomes, Indigenous outcomes have largely deteriorated if they haven’t stagnated.

Out of this well of eternal disappointment has emerged the central idea underpinning the Voice: that the solution to Indigenous Disadvantage lies in Indigenous hands. Australian governments must delegate control, authority and decision-making power to Indigenous communities and their leaders, who are in the best position- both morally and practically- to make decisions for themselves, and in doing so Close the Gap. …

And herein lies the central myth responsible for the incoherence of the Voice movement: that Indigenous communities suffer from a lack of consultation or self-determination, and that changing this will improve outcomes.

Those who believe in self-determination as the solution to Indigenous Disadvantage are many, and they are misled. In reality, self-determination was introduced as the reigning policy paradigm for Aboriginal affairs by the Whitlam government in 1972. … In 1973 the Whitlam Government even set up a body that functioned almost identically to the proposed Voice: the National Aboriginal Conference (NAC). This was a body of elected Indigenous representatives with the explicit purpose to advise the government on all policies and issues relating to Indigenous peoples. Sound familiar?

The NAC was disbanded by the Hawke government in 1985 after a decade of lamenting that its recommendations were not binding, advocating for treaty (it is responsible for the popularisation of the term makarrata), infighting, and financial mismanagement. NAC was followed by the better known Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), which again operated (poorly) under the framework of Indigenous self-determination and consultation until its demise in 2005. …

Community consultation is the approach du jour; it is the approach de hier. [Charles is a native French speaker and may not know that some of us who don’t have to look up ‘du jour’ do have to look up ‘de hier’]. …

Which leaves us today, recycling ideas from 1973, choosing to pretend that self-determination or consultation has never been tried, unable to reconcile with the utter mess that has been created across Australia’s interior. It is for this reason that it remains an open question whether Linda Burney really believes it when she proclaims that the Voice will Close The Gap. The notion is absurd on its face to anyone who has grappled honestly with the reality of Indigenous Disadvantage, or with our failed history of attempting to remedy it.

The true causes of Indigenous Disadvantage lie beyond the scope of this essay, but an honest reckoning would require nothing less than an ideological revolution upending a half-century of failed establishment orthodoxy. In the end, for many Australians who are voting Yes, whether or not the Voice works does not matter. It is beside the point. The Voice exists as yet another symbolic gesture of repentance and reparation which defines the nation’s relationship to its Indigenous minority. And for the Indigenous elite who sponsor it, it represents the assertion of the power of Aboriginal identity politics for the sake of asserting power.

Regardless of whether the Australian people vote Yes or No, Australia is condemned to its guilt.

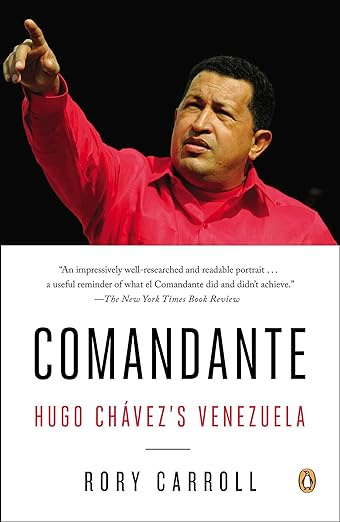

Must read: Scott Alexander on Rory Carroll on Hugo Chavez

When Donald Trump was campaigning for the presidency, I’m among the people whose gob was smacked, whose ghast was flabbered that he won. But I did wonder how many people might vote for him because, well you know, government isn’t all that important, how could anything go really wrong, so why not have some fun. We’re voting for eviction and it’s certainly more fun to evict the unlikeable Hilary than the funny idiot Trump.

I think I was on to something, but now I see the whole issue as a much deeper one. Political communication is, as a matter of economic fact, a substantial but ultimately smallish part of the entertainment industry. And from the inside, if you’re a politician, pretty much all your attention goes to getting other people’s attention — via mass and social media.

And the dramaturgy of this situation (if that’s the right word) seeps into people’s consciousness. People themselves are the audience — the flattered audience of our politicians. We tune in when it grabs us. When our ‘engagement’ is high as the metrics would have it.

We have simply imbibed the idea of politics as entertainment. How often have you heard that a politician is just boring as a potentially terminal flaw. It’s ridiculous, but there you go — that’s our entertainmentocracy.

In any event, Scott Alexander is doing a survey of the great dictators and authoritarian populists of the world and Hugo Chavez’s number came up. I had no knowledge of him other than that he was a left wing South American politician who ran his oil rich country into the ground. But as Scott says, this is the scariest profile he’s done. Chavez kind of more or less turned his dictatorship into a TV show.

If he had been an ordinary celebrity, he would be remembered as a legend. But he went too far. He became his TV show. He optimized national policy for ratings. The book goes into detail on one broadcast in particular, where he was filmed walking down Venezuela’s central square, talking to friends. He remarked on how the square needed more monuments to glorious heroes. But where could he put them? The camera shifted to a mall selling luxury goods. A lightbulb went on over the dictator’s head: they could expropriate the property of the rich capitalist elites who owned the mall, and build the monument there. Make it so! Had this been planned, or was it really a momentary whim? Nobody knew.

Then he would move on to some other topic. An ordinary citizen would call in and describe a problem. Chavez would be outraged, and immediately declare a law which solved that problem in the most extreme possible way. Was this staged? Was it a law he had been considering anyway? Again, hard to tell.

Sometimes everyone in government would ignore his decisions to see if he forgot about them. Sometimes he did. Other times he didn’t, and would demand they be implemented immediately. Nobody ever had a followup plan. They expropriated the mall, but Chavez’s train of thought had already moved on, and nobody had budgeted for the glorious monuments he had promised. The mall sat empty; it became a dilapidated eyesore. Laws declared on the spur of the moment to sound maximally sympathetic to one person’s specific problem do not, when combined into a legal system, form a great basis for governing a country.

But Chavez TV was also a game show. The contestants were government ministers. The prize was not getting fired. Offenses included speaking out against Chavez:

Chavez clashed with and fired all his ministers at one time or another but forgave and reinstated his favorites. Nine finance ministers fell in succession . . . it was palace custom not to give reasons for axing. Chavez, or his private secretary, would phone the marked one to say thank you but your services are no longer required. Good-bye. The victim was left guessing. Did someone whisper to the comandante? Who? Richard Canan, a young, rising commerce minister, was fired after telling an internal party meeting that the government was not building enough houses. Ramon Carrizales was fired as vice president after privately complaining about Cuban influence. Whatever the cause, once the axe fell, expulsion was immediate. The shock was disorienting. Ministers who used to bark commands and barge through doors seemed to physically shrink after being ousted . . . they haunted former colleagues at their homes, seeking advice and solace, petitioning for a way back to the palace. ‘Amigo, can you have a word with the chief?’ One minister, one of Chavez’s favorites, laughed when he recounted this pitiful lobbying. “They know it as well as I do. In [this government] there are no amigos.”

…or taking any independent action:

[A minister] was not supposed to suggest an initiative, solve a problem, announce good news, theorise about the revolution, or express an original opinion. These were tasks for the comandante. His fickleness encouraged ministers to defer implementation until they were certain of his wishes. In any case they spent so much time on stages applauding - it was unwise to skip protocol events - that there was little opportunity for initiative.

And on and on it goes. Well worth checking out.

Godfrey Miller

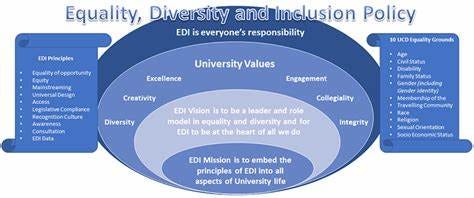

If inequality is fractal, woke is window dressing — or maybe worse

This article has a very strange ‘theory of change’ when it asks why has popular culture been prioritized for change. It wasn’t a central plan but came out of the various economic and ideological forces on the various players. Be that as it may the point it makes is fundamental. Most activity that’s supported on the basis of diversity and inclusion is performative. It maximises legibility, rather than improving outcomes for the disadvantaged.

For a generation or two lots of kids who gained advantages in accessing upper class education from poorer countries — I’m thinking of Eton and Oxford and Cambridge — were often the children of the rich, but they were the right colour to help make things look diverse. And maybe that’s a good thing when you look at what a remarkable share of British senior politicians are people of colour and of different religious and cultural backgrounds. Good old Eton. But it’s not too clear they’re tackling inequality.

“You got 1 percent of the population in America who owns 41 percent of the wealth… but within the black community, the top 1 percent of black folk have over 70 percent of the wealth. So that means you got a lot of precious Jamals and Letitias who are told to live vicariously through the lives of black celebrities so that it’s all about ‘representation’ rather than substantive transformation… ‘you gotta black president, all y’all must be free.’”

– Cornel West interviewed by Joe Rogan, July 24, 2019

Of all the industries in desperate need of change, why has popular culture been prioritized? There is at least one generally statable reason, and it has to do with the fact that despite a falling share of the population, white Americans still outnumber Black Americans six-to-one. For every white American to have even one Black friend, every single Black American, including newborns, would need to have six white friends. This demographic constraint makes popular culture the primary medium through which white Americans engage with Black ones. This pop cultural experience is optional, and, in my experience, white folks usually do not pursue it to satisfy a broad and general curiosity about Black people. Rather, engagement is motivated by the belief that popular culture can connect white Americans to Black ones—and to the Black poor in particular—while, simultaneously, providing an arena for redressing the violence that white Americans have done to the Black poor. …

I was born into Black poverty, and I will not forget that George Floyd was born into the same. For Floyd, the particulars of poverty were this: to be raised in the Cuney Homes projects, to endure years of deprivation, and to die violently in a manner common to our caste. Were Floyd still alive, or somehow reborn, he would not be hired to work within any of the institutions which now produce popular culture in his honor because he never obtained a bachelor’s degree.

A decade of unprecedented interest in Black arts and letters has now passed—the greater portion of it bought with footage of people possessing Floyd’s particulars lying dead on the tar—and still you cannot walk into a bookstore to find a shelf named for Black authors raised in poverty. That category of experience remains absent amidst the dozens of shelves now labeled for Black authors of every other identity and intersection. I accept that Floyd’s final suffering becomes a political currency for the many, but I struggle with the fact that it purchases opportunities for the Black middle- and upper- classes, without securing a pen or a publisher for the children of Cuney Homes, without an expectation that it should, and without condemnation that it doesn’t. …

To go back to the 2020 National Book Award nominees for a moment, three of the authors were Black and two were Black women. Deesha Philyaw graduated from Yale, and Brit Bennet from Stanford. Jesmyn Ward—a Black woman, and the only woman to twice win the NBA for fiction (2011, 2017)—attended Stanford and then the University of Michigan, the latter considered a sort of public Ivy. In 2020, The New Yorker had nine visibly Black contributors (of which seven are men). All nine graduated from four-year colleges, and more than half gained their credentials at elite universities2. Based on publicly available biographies, compared to their non-Black peers, Black contributors had a higher rate of Ivy League attendance and were twice as likely to be college faculty. …

Above-average privilege, particularly in terms of income, is the norm for successful creators both white and Black, but the ignorance that obscures the economic privilege of the latter group provides a bitter irony when you’re a formerly impoverished Black person operating in a highly educated milieu. The only time that someone recommends Colson Whitehead or Roxanne Gay to me—really, the only time any Black creator outside of music is recommended to me by a white person—is when the person I am talking to learns that I am from the Black underclass. Being Black and from poverty, I am what white Americans imagine they are learning about and “standing in solidarity” with when they imbibe popular culture’s Black offerings. But it never occurs to them that Whitehead and Gay come from a very different class to begin with, and are not necessarily standing in real solidarity with me. …

If I were from a different community, pointing out the economic disparities in popular culture—let alone in prison—might yield some kind of intervention on our behalf or at least warrant a call for one. But I am from the Black poor. What afflicts us does not belong to us—it belongs to the race, to the class-free abstractions of “Black people,” “Black communities,” “Black families.” That is the only representation we receive, and so long as this is the framing, no exclusion, no oppression, no suffering endured by us will be understood as warranting a solution designed specifically for us.

The ease with which Coates transitions from naming forms of oppression that predominantly afflict the Black poor to making class-blind statements about “Black experience” is common everywhere. Speaking about his love for Serena Williams on the For Colored Nerds podcast in 2017, Vann Newkirk II—the most prominent Black journalist at The Atlantic since Ta-Nehisi Coates’ departure—said:

“She [Williams] to me is like Ali in that she provides that public voice that public excellence that we often need when we’re feeling down when we feel like you know maybe they won’t stop killing us, maybe they won’t stop marginalizing us and redlining us and putting us on the edge of cities and flood plains and lead poisoning us.”

If you accept the argument I’ve presented thus far, you might assume Newkirk’s place in popular culture via his job at The Atlantic means he has a bachelor’s degree. You might then assume that he was raised in the middle- or upper- class. The ethical thing to do, however, is to assume nothing and look him up. If you do that… you will find that Newkirk graduated from Morehouse and then UNC Chapel Hill. His mother was a public-school teacher, and his father is a Howard University PhD and the president of Fisk University, a position commanding $120,308 annually.

Newkirk says “us” and “we,” but it’s doubtful that he was actually raised in a redlined project with lead-lined walls and too many police. But he talks in a way that implies some biographical connection between himself and forms of oppression that, for the public, are bywords for poverty: dog whistles of a kind. This way of speaking, heavy in its use of first-person pronouns with regards to stereotypical oppressions, is how most middle- and upper- class Black people working in popular culture speak—not because it is the most accurate, but because it fosters the appearance of being real Black. …

If I were from a different community, pointing out the economic disparities in popular culture—let alone in prison—might yield some kind of intervention on our behalf or at least warrant a call for one. But I am from the Black poor. What afflicts us does not belong to us—it belongs to the race, to the class-free abstractions of “Black people,” “Black communities,” “Black families.” That is the only representation we receive, and so long as this is the framing, no exclusion, no oppression, no suffering endured by us will be understood as warranting a solution designed specifically for us.

The ease with which Ta-Nehisi Coates transitions from naming forms of oppression that predominantly afflict the Black poor to making class-blind statements about “Black experience” is common everywhere. Speaking about his love for Serena Williams on the For Colored Nerds podcast in 2017, Vann Newkirk II—the most prominent Black journalist at The Atlantic since Ta-Nehisi Coates’ departure—said:

“She [Williams] to me is like Ali in that she provides that public voice that public excellence that we often need when we’re feeling down when we feel like you know maybe they won’t stop killing us, maybe they won’t stop marginalizing us and redlining us and putting us on the edge of cities and flood plains and lead poisoning us.” [author’s emphasis].

Mike Tyson is a smart guy — like so many heavyweight champions. Like he says, most of the stuff the commentators say is not’n. Anyway this is a fun moment that happens shortly afterward.

Fascinating data on the decline of youth mental health

Roser is correct that overall suicide rates are not increasing across all nations. But it would be a mistake to conclude that the United States is unique, or that there is not a worrying international trend in youth suicide rates. Here are four reasons why:

Those graphs fail to break results down by sex. The mental health crisis is gendered, with girls showing the most substantial and rapid changes in mental illness since the early 2010s.

They fail to consider how young people are doing relative to older people in each country. Anxiety rates are surging among youth, while only slightly increasing for U.S. adults. Perhaps suicide rates overall are dropping, but not for young people, or not as fast for young people. If so, we’d still want to know: why are young people not sharing in the decline in suicide?

They don’t break out data for 10-14-year-olds, where there are the largest relative increases since 2010 in poor mental health. (These effects are harder to see on graphs that also show older age groups because of the low base rates for 10-14-year-olds).

They fail to consider cultural variation. While there has been a global decline in suicide rates over the past century, particularly among older adults in non-western nations, my previous posts have found significant regional and cultural effects on mental health outcomes. Thus, some cultural variation should be expected, rather than immediately seen as counter-evidence.

Rebooting the university

I was intrigued by this lengthy profile of various attempts to reboot the university. Despite their ideologies, I really wish them well given how sadly existing universities have collapsed into careerism. Then again as Steven Pinker who spent one week on the advisory board of UATX but was often mistaken for a founding faculty member said, “It seemed to be organised not around a coherent vision for higher education, in which you could rethink every detail, but rather as a kind of a politically incorrect university with a faculty of the cancelled. Just rounding up people who’ve been persecuted, however unjust it has been to them, that does not yield a coherent curriculum.”.

UATX was announced in November 2021 as being “dedicated to the fearless pursuit of truth”, on former New York Times journalist Bari Weiss’s Substack. Weiss, 39, is widely disliked among US liberals. Although she is only one of the college’s board of trustees, “Bari Weiss’s anti-cancel-culture university” (Vanity Fair) was panned as a “fake” (The Guardian) and an “epic clown show” (Nation writer Jeet Heer, posting on X), among other things.

Kanelos, who grew up in Chicago reading at the back of his parents’ Greek diner, is no culture warrior or free-speech absolutist. He comes across as nuanced, undogmatic. He chose to leave a plum job as president of a respected liberal arts university, St John’s College in Maryland, to co-found UATX. “My motivation here is really simple,” he says. “The world is coming apart at the seams. We live in a time of a kind of ambient nihilism. The only response is to build and create.” …

UATX has managed to raise nearly $200mn from more than 2,400 donors. Thirty-two of those gave more than $1mn. That probably has something to do with the people involved. Many trustees and advisers — Richard Dawkins, Niall Ferguson, Arthur Brooks, Jonathan Haidt, Larry Summers — are celebrity academics with large followings. One co-founder is Joe Lonsdale, a venture capitalist and a longtime associate of Peter Thiel’s. Guest lecturers include billionaire Marc Andreessen, who came to speak at Forbidden Courses, UATX’s summer programme. (The college declined to say whether Andreessen is a donor.)

Although UATX has been described as conservative, Kanelos insists it is “non-political”. “If you’re going to have institutions that are foundationally committed to the discovery, transmission and preservation of knowledge, their operating system has to be a liberal one,” he says. “But commitment to those principles doesn’t necessarily line up with politically liberal” — he air quotes — “or conservative today. There are people on the right who are illiberal and people on the left who are illiberal.” …

I am the first journalist to be allowed inside UATX. My initial request to visit was denied. Eventually, I agreed that I wouldn’t attend seminars, where debate among students takes place. One of the main criticisms in The Coddling of the American Mind is that US colleges are being turned into “safe spaces”. It strikes me that I am visiting a series of safe spaces of a different kind at these new colleges too.

A stunner

Arendt on Lessig

Last weekend I read a stunning speech by Hannah Arendt accepting the Lessing Prize in 1959. Here is an extract. You can download the full speech at this link.

Lessing experienced the world in anger and in laughter, and anger and laughter are by their nature biased. Therefore, he was unable or unwilling to judge a work of art "in itself," independently of its effect in the world, and therefore he could attack or defend in his polemics according to how the matter in question was being judged by the public and quite independently of the degree to which it was true or false. It was not only a form of gallantry when he said that he would "leave in peace those whom all are striking at"; it was also a concern, which had become instinctive with him, for the relative rightness of opinions which for good reasons get the worst of it. Thus even in the dispute over Christianity he did not take up a fixed position. Rather, as he once said with magnificent self-knowledge, he instinctively became dubious of Christianity "the more cogently some tried to prove it to me," and instinctively tried "to preserve it in [his] heart" the more "wantonly and triumphantly others sought to trample it underfoot." But this means that where everyone else was contending over the "truth" of Christianity, he was chiefly defending its position in the world, now anxious that it might again enforce its claim to dominance, now fearing that it might vanish utterly. Lessing was being remarkably farsighted when he saw that the enlightened theology of his time "under the pretext of making us rational Christians is making us extremely irrational philosophers." That insight sprang not only from partisanship in favor of reason. Lessing's primary concern in this whole debate was freedom, which was far more endangered by those who wanted "to compel faith by proofs" than by those who regarded faith as a gift of divine grace. …

We very much need Lessing to teach us this state of mind, and what makes learning it so hard for us is not our distrust of the Enlightenment or of the eighteenth century's belief in humanity. It is not the eighteenth but the nineteenth century that stands between Lessing and us. The nineteenth century's obsession with history and commitment to ideology still looms so large in the political thinking of our times that we are inclined to regard entirely free thinking, which employs neither history nor coercive logic as crutches, as having no authority over us. To be sure, we are still aware that thinking calls not only for intelligence and profundity but above all for courage. But we are astonished that Lessing's partisanship for the world could go so far that he could even sacrifice to it the axiom of noncontradiction, the claim to self-consistency, which we assume is mandatory for all who write and speak. For he declared in all seriousness: "I am not duty-bound to resolve the difficulties I create. May my ideas always be somewhat disjunct, or even appear to contradict one another, if only they are ideas in which readers will find material that stirs them to think for themselves." …

In the two hundred years that separate us from Lessing's lifetime, much has changed in this respect, but little has changed for the better. The "pillars of the best-known truths" (to stay with his metaphor), which at that time were shaken, today lie shattered; we need neither criticism nor wise men to shake them anymore. We need only look around to see that we are standing in the midst of a veritable rubble heap of such pillars.

Now, in a certain sense, this could be an advantage, promoting a new kind of thinking that needs no pillars and props, no standards and traditions to move freely without crutches over unfamiliar terrain. But with the world as it is, it is difficult to enjoy this advantage. For long ago it became apparent that the pillars of the truths have also been the pillars of the political order, and that the world (in contrast to the people who inhabit it and move freely about in it) needs such pillars in order to guarantee continuity and permanence, without which it cannot offer mortal men the relatively secure, relatively imperishable home that they need. To be sure, the very humanity of man loses its vitality to the extent that he abstains from thinking and puts his confidence into old verities or even new truths, throwing them down as if they were coins with which to balance all experiences. And yet, if this is true for man, it is not true for the world. The world becomes inhuman, inhospitable to human needs—which are the needs of mortals—when it is violently wrenched into a movement in which there is no longer any sort of permanence. That is why ever since the great failure of the French Revolution, people have repeatedly re-erected the old pillars which were then overthrown, only again and again to see them first quivering, then collapsing anew. The most frightful errors have replaced the "best-known truths," and the error of these doctrines constitutes no proof, no new pillar for the old truths. In the political realm, restoration is never a substitute for a new foundation but will be at best an emergency measure that becomes inevitable when the act of foundation, which is called revolution, has failed. But it is likewise inevitable that in such a constellation, especially when it extends over such long spans of time, people's mistrust of the world and all aspects of the public realm should grow steadily. For the fragility of these repeatedly restored props of the public order is bound to become more apparent after every collapse, so that ultimately the public order is based on people's holding as self-evident precisely those "best-known truths" which secretly scarcely anyone still believes in.

The Guru, the bagman and the sceptic

I mentioned this book in my previous newsletter (it’s really fantastic) and also my hope to be interviewing the author. I have now done that and it was great. I hope to get it to you in the next two or three weeks. In the meantime, here’s some more of his book.

Chapter 15

In the now largely forgotten 1983 film Lovesick, the ghost of Sigmund Freud (Alec Guinness) tells the apostate New York analyst Saul Benjamin (Dudley Moore) that psychoanalysis ‘was intended only as an experiment, never as an industry’. But that is exactly what it was: Freud’s enduring legacy was a new profession. In a form of apostolic succession, all analysts could connect themselves, directly or indirectly, to him. Freud laid down the basic rules in his 1913 paper, ‘On Beginning the Treatment’. The session should last an hour. The analyst and the analysand should agree on the fee before commencing: ‘Nothing brings home to one so strongly the significance of the psycho-genic factor in the daily life of men, the frequency of malingering, and the non-existence of chance, as a few years’ practice of psychoanalysis on the strict principle of leasing by the hour.’ The patient should be charged for no-shows; the patient should take holidays only during the same time as the analyst and should be charged the full fee if away on holiday while the analyst was working. The analyst should collect payments regularly and should always charge: ‘Free treatment enormously increases some of the neurotic’s resistances. The absence of the regulating effect offered by the payment of a fee to the doctor makes itself very painfully felt; the whole relationship is removed from the real world, and the patient is deprived of a strong motive for endeavouring to bring the treatment to an end.’1 (Freud famously sent a very late invoice to Gustav Mahler’s widow for his four-hour walk-and-talk with the composer in Leiden in 1910.) Freud’s only other requirement was that his patients should ‘possess a reasonable degree of education and a fairly reliable character’, which would bar both the poor and those with personality disorders.

Freud worried a great deal about money – not because he was greedy, but because he supported up to twelve people at any time; his dependents included his wife and six children, his two sisters and his sister-in-law Minna.2 As a young married man, he was obliged to borrow occasionally, and deeply resented those who lent to him. Lack of money and lack of prospects (because he was a Jew) forced the young Freud out of academic life into work as a private neurologist, where most of his patients had symptoms that were psychosomatic in origin. Thus it was that economic necessity and anti-Semitism led to Sigmund Freud’s third-choice career, ministering to a fee-paying clientele of ‘hysterical’ patients.

‘What is the use of Americans, if they bring no money?’ Freud asked Jones. ‘They are not good for anything else.’ In the early 1920s, many of them came to Vienna to be analysed with the sole aim of setting themselves up in analytic practice on their return. Most of these pilgrims were not medically qualified, and so gravitated to Otto Rank, ‘lay’ analyst and Paladin. When Jones indignantly asked Rank ‘how he could bring himself to send back to America as a practising analyst someone who had been with him barely six weeks’, Rank shrugged his shoulders and replied: ‘one must live.’ Psychoanalysis had become a franchise.

Like Freud, Ernest Jones had to make his own way in the world. When he returned to London in 1913, he soon realised that psychoanalysis was, from an economic perspective, unlike any other branch of medicine. Because the appointments were so long (an hour) and so frequent (several times a week), and because therapy went on for years, or even decades, he needed only eight patients at any one time to make a good living. The downside of this model was that the departure of even one patient was a serious loss; this undoubtedly encouraged analysts to take a lenient and forgiving approach to patients with ‘transference problems’. Around this time, an advertisement appeared in the London Evening Standard from the bogus English Psycho-Analytical Publishing Company: ‘Would you like to make £1,000 a year as a psychoanalyst? Take eight postal lessons from us at four guineas a course.’

In the early years, patients were few and highly prized: in 1914, there were only thirty to forty analysands in the whole of London, eight of whom were with Jones. The pool of such patients was narrow and shallow; they came almost exclusively from the upper-middle-class elite who occupied the squares and terraces of Bloomsbury and the high tables at Cambridge. The historian Gordon Leff recalled that his mother, one of ‘the bright young things of the 1920s’, had been given ‘a full analysis’ as a wedding present.

Jones was a prodigious worker: he saw up to eleven patients a day, wrote numerous papers and books, and ran the British Psychoanalytical Society. When he started his London practice, Jones’s standard fee was a guinea an hour; some wealthier patients (like Ethel Vaughan-Sawyer) paid two guineas. By 1928, his fee had risen to three guineas. His lucrative practice eventually funded a fine Nash house in York Terrace, a country house (renovated by Freud’s architect son, Ernst), a cottage in Wales and a summer house in Menton on the French Riviera.

The Freudians made the occasional feeble claim to treat the less well-off, but this was generally done only by analysts in training, who charged a reduced rate. (This arrangement allowed the impecunious Samuel Beckett to be treated by the tyro analyst Wilfred Bion in the 1930s.) Psychoanalysts are very prickly about the perception that they cater only for the well-off. The psychoanalyst and author Adam Phillips claimed – rather unconvincingly – that psychoanalysis is ‘a psychology of, and for, immigrants’, but you can be sure that the hotel chambermaid and the Deliveroo cyclist aren’t free-associating on an analyst’s couch during their free time.

There was much bickering over fees. When Donald Winnicott, then a young paediatrician, was in analysis with James Strachey, he had a habit of ‘forgetting’ or delaying paying his fees; he also failed to pay Ernest Jones on several occasions. Dissatisfied with Strachey (with whom he had been in analysis for ten years), he moved on to Joan Riviere, whom he tried to convince that he could only afford one guinea per session. When she found out that Winnicott was very well-off – his father, Sir John, was a wealthy businessman – she wrote to him to point out that two guineas was a relatively low fee for a ‘front rank’ analyst such as herself: ‘I am second to no one in ability.’ She later decided that Winnicott’s stinginess was down to transference-induced envy: ‘It is because it has become clear that you undervalue my work that I think it is right to ask if you can pay my full fee.’

Janet Malcolm’s 1981 book Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession is an amusing insight into the business side of the discipline. She told the story through the work of one analyst, whom she called ‘Aaron Green’. He advised one patient that because he (Green) took holidays in August, she would have to pay for missed sessions when, one year, she took holidays in July. ‘She found this intolerable,’ wrote Malcolm; ‘he wouldn’t back down; and she left the analysis.’ Green rationalised this psychoanalytically: ‘My blunder was that I didn’t understand and interpret the transference soon enough, I didn’t point out to her that she was taking flight because she couldn’t face her painful feeling of love towards me. I didn’t convince her that the money she wouldn’t part with was the phallus-child she wanted from me.’

It is not surprising that psychoanalysis attracted so many would-be practitioners, particularly in the 1920s, when several lay analysts set up in practice with no qualification other than having been analysed themselves. Even Wilfred Trotter admitted to Jones that he could not imagine a more agreeable way of earning money than ‘telling people what you really thought about them’. (I think Trotter got this wrong – analysts rarely told their patients what they ‘really thought about them’.) Psychoanalysis – particularly during its imperial phase in America – was a much more attractive option than mainstream hospital-based psychiatry, being well paid, with no weekend or night work, and no frightening psychotic patients. Janet Malcolm wrote enviously about the older New York analysts’ apartments on Fifth Avenue and Park Avenue.

*

Just as very long books tend to be overpraised, patients who have undergone long and expensive psychoanalysis tend to claim that it cured them. One of the most revealing expositions of the economics of psychoanalysis from the analysand’s perspective is the American writer Francis Levy’s account of his decades-long therapy: ‘Psychoanalysis: The Patient’s Cure’, published in American Imago in 2010. Levy, a struggling writer, went into analysis, it seems, because he couldn’t reconcile himself to the bleak truth that he wasn’t as good as John Updike. Luckily, however, he had inherited a lot of money, and he began analysis in the late 1970s, paying $70 for a fifty-minute session, rising to $250 in 2000.

Levy sees Dr S. four days a week: ‘For some time we had been working on what is technically known as narcissistic grandiosity. We’re not friends, but colleagues who’ve been working on something together for years.’ The average duration of a full analysis steadily increased from two to four years in the 1930s and 40s, to four to six years in the 1950s and 60s, to six to eight years in the 1970s. ‘The majority of analytic cases end’, wrote Janet Malcolm, ‘because the patient moves to another city, or runs out of money.’ Freud admitted that if he found a patient who was ‘interesting but not too troublesome’, and could afford his fee, it was easier for him to continue analysis indefinitely.

Dr S., the son of Austrian immigrants, plays the violin, is a Harvard graduate, and ‘sighs a lot’. When he raised his fee from $315 to $350, it prompted Levy to do some quick calculations: ‘Let’s say I’ve seen Dr S. approximately forty-two weeks of the year, four times a week for twenty-nine years, for a total of 4,872 visits. By my calculations, that’s close to $1,000,000 in fees. I ignore my father’s voice saying, Sure he likes you, why wouldn’t he, you’ve made him rich.’ Dr S.’s Carnegie brownstone, which he bought for $165,000 in 1962, is now worth $5 or $6 million; he takes eight weeks’ holiday a year, staying at hotels like the Hotel du Cap, the Connaught and the Cipriani. ‘My wife and I’, wrote Levy mournfully, ‘have often observed that during summer vacations, when our analysts were away, we were like two siblings left alone at home by their parents.’

*

There have been a few challenges to the Freudian hour. As Sándor Ferenczi grew older, his methods became ever wilder. He would analyse patients for hours on end, throughout the day and often into the night. He did, however, tell this good joke about fees:

The most characteristic example of the contrast between conscious generosity and concealed resentment was given by the patient who opened the conversation by saying: ‘Doctor, if you help me, I’ll give you every penny I possess!’ ‘I shall be satisfied with thirty kronen an hour,’ the physician replied. ‘But isn’t that rather excessive?’ the patient replied.

Jacques Lacan, the French neo-Freudian, had his own unique variation on the analytic hour. He questioned the sacrosanct fifty minutes, arguing that a shorter session turned ‘the transference relationship into a dialectic’. Lacan was repeatedly cautioned about this by the International Psychoanalytical Association and was eventually expelled. He reduced the session over time to ten minutes but did not reduce his fee; during these mini analyses, he would often see his tailor, pedicurist and barber. This new business model allowed Lacan to see up to eighty patients a day; he died a multimillionaire, leaving a legacy of discarded lovers, several patients who died by their own hand, and a dozen or more psychoanalytic societies and associations, each claiming to be the true heir to his progressive and revolutionary ideas.

1 Freud often broke this rule; he treated several patients for free, including Heinz Hartmann, Eva Rosenfeld and even, for a time, the Wolf Man.

2 Whether Freud did or did not have an affair with Minna has exercised Freudian scholars for many decades.