From repressive tolerance to repressive diversity

And other great things I found on the net this week

From repressive tolerance to repressive diversity

Herbert Marcuse coined the expression ‘repressive tolerance’. It took off — as well it might. It’s an important idea, providing one keeps in mind that there are very few situations in which repressive tolerance isn’t better than repressive intolerance! Indeed, showing the motivated impatience so typical of Western intellectuals, Marcuse showed how you can take the idea and retrofit it to — well whatever you like.

Liberating tolerance, then, would mean intolerance against movements from the Right and toleration of movements from the Left.

Voila! Job done. Bob’s your uncle.

Anyway, this leads me to coin the expression repressive diversity. And I’m not sure it is better than its opposite. As the Sydney Review of Books informs us:

Eda Gunaydin is a Turkish-Australian essayist and researcher whose writing explores class, capital, intergenerational trauma and diaspora.

There’s certainly nothing wrong with any of these subjects. But how come they so dominate the discussion of difference? Could that be a kind of cultural dominance itself? Note how the blurb could be about any difference or deviance from what was honoured in the dominant culture whether it was based on sex, gender, race, disfigurement, disablement, neurodiversity and on and on. So really, each of these exercises is primarily about the dominant culture and its endlessly rehearsed inadequacies — though those inadequacies are invariably against some theoretical (and so utopian) standard rather than by comparison with other existing existing cultures.

Should the dominant culture be more broadminded and inviting? Sure should. But then we should all be kinder. I should have been kinder yesterday. So should you. But what about all the things in a person’s history that might be different that might enrich our lives rather than simply provide a benchmark by which to grade our own culture’s intolerance. They’d be particular things, and having articulated them, one might find connections between them, and between them and the dominant culture. But they wouldn’t be, in the first instance, generic ones.

Ray Monk on Oppenheimer

Very interesting interview with a very nice fellow — Ray Monk, biographer of Robert Oppenheimer. With a great explanation of why the allies got the bomb first from a private secretary of Churchill. “Our Germans were better than theirs”.

Christos is not impressed

I haven't seen it yet, but want to.

There is no denying Nolan’s strength as a director, his ability to create visually elating sequences that are breathtaking in their precision and execution. There is a key moment in Oppenheimer when the first atomic bomb is detonated in New Mexico. The filmmaking here is sublime, not only in the care taken with the imagery and framing but also in the attention to the reactions and emotional commitment of his cast of actors. The editing is propulsive yet never overwrought. Nolan successfully makes the explosion both truly beautiful and truly terrifying.

Yet whatever his abilities as a filmmaker, ill-discipline when it comes to narrative has been Nolan’s Achilles heel almost from the beginning of his career. …

Nolan wants us to be awed by the dangerous miracles spawned by revolutionary science but doesn’t have the patience to write any film scenes in which we are animated by intellectual argument. There are moments when I sat up in my seat, when ideas concerning quantum physics and the conflict of these new ideas with Einsteinian precepts are beginning to be discussed, but as soon as they are brought up Nolan cuts away to rhetorically empty images of star systems. This distrust of us as an audience, this belief that we can’t be thrilled by argument, is a disastrous flaw in the film.

There is an equivalent laziness in the moral questions at the heart of Oppenheimer. The scenes involving Strauss’s senate bid are filmed in black and white, and in this, alongside the Manichean conception of Strauss, there are echoes of the hyperbolic excesses of George Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck (2005). These senate scenes dominate the film’s last hour and they are truly execrable. Any finesse Downey Jr brought to his early scenes is destroyed in the increasingly preposterous histrionics of his character. The scenes also undermine Nolan’s intentions to frame Oppenheimer’s life and legacy in mythic terms. Strauss is reduced to such a cartoonish villain that there is no equivalence between his succumbing to the seductions of power and that of Oppenheimer’s temptation. We experience no sense of the tragic. …

English-language American films are now dominated by an obsession with the adolescent. Oppenheimer is marketed as a return to truly adult filmmaking. Yet in its conception of science, and in its moral sentimentality, it is as undergraduate as anything from the Marvel franchise. Nolan’s self-conception as Hollywood’s saviour, the man who will bring maturity back to the movies, might be the real hubris.

On Julien Benda's The Treason of the Intellectuals (1927)

In the same way that each of us has had to grow up to resist the temptation of wishful thinking … so our species has had to learn in growing up that we are not playing the starring role in any sort of grand cosmic drama.

Steven Weinberg, Dreams of a Final Theory

Having come across this book and having had a bit of a poke around in it previously, I was reminded of it twice this week, once by reading of it in The German Genius and via this piece by Justin Murphy. I think he is right — it’s a big deal. Somehow, some time in the early 19th-century the Western intelligencia started throwing the switch to megalomania. It became all about them and the systems of ideas they cooked up. It’s not been a happy couple of centuries since (though the 19th did go quite well from 1815 to 1914!

In 1927, the French essayist Julien Benda published a short book called La Trahison des Clercs or, as it would be translated in America, The Treason of the Intellectuals. … Historically, the great thinkers are generally disinterested and metaphysical, he argues. They are oriented toward the highest values, which are always to some degree mutually exclusive with power, profit, and status—often, the values of the intellectual are not of this world at all.

Before the nineteenth century, history is “filled with long European wars which left the great majority of people completely indifferent… Today there is scarcely a mind in Europe which is not affected—or thinks itself affected—by a racial or class or national passion, and most often by all three.”

Today, it’s easy to see that this trend has continued for the century after Trahison. A distant war between Russia and Ukraine inflames national sensibilities in the United States, while class identity is experienced as an intersection between new and increasingly trivial categories.

Why? The Trahison.

The treason of the intellectuals was committed when they—as a class, especially from around the 1870s onward—became overtaken by certain modern passions. Especially nationality and race, but we’re talking about something more general than that:

“It seems to me that these passions can be reduced to two fundamental desires: (a) The will of a group of men to get hold of (or to retain a hold on) some material advantage, such as territories, comfort, political power and all its material advantages; and (b) the will of a group of men to become conscious of themselves as individuals, insofar as they are distinct in relation to other men… One [desire] seeks the satisfaction of an interest, the other of a pride or self-esteem.”

Julien Benda, The Treason of the Intellectuals

In short, public intellectuals became infected with the mental virus of politics.

Benda seems to place the blame initially on the German nationalist intellectuals like Lessing, Schlegel, and Fichte. But from there it spreads everywhere in the West and reaches fever pitch in the 20th century. And it’s true: From Ezra Pound’s fixation with Fascism to Sartre’s fixation with Soviet communism, 20th century intellectual life was a massive capitulation to, and normalization of, political axe-grinding. In the name of an instrumental “realism” that Benda diagnoses expertly.

What is most interesting about reading this book today is that Benda could even experience this defection of the intellectuals as a problem. It feels so distant and quaint. We are so past the completion of this defection that Benda's indignation almost fails to parse. We have so fully capitulated to what Benda calls "realism" that the average reader today will be confused by the word. He says it like it's a bad thing?

But for all of these reasons, I found this book productively disruptive; it gave me a jolting sense of shame. We are all so adjusted to one generic calculative layer of the world. Living after the treason of the intellectuals, we live in a cultural space that is even flatter than we realize.

The treason of the students (maybe most of us?)

From Brink Lindsay:

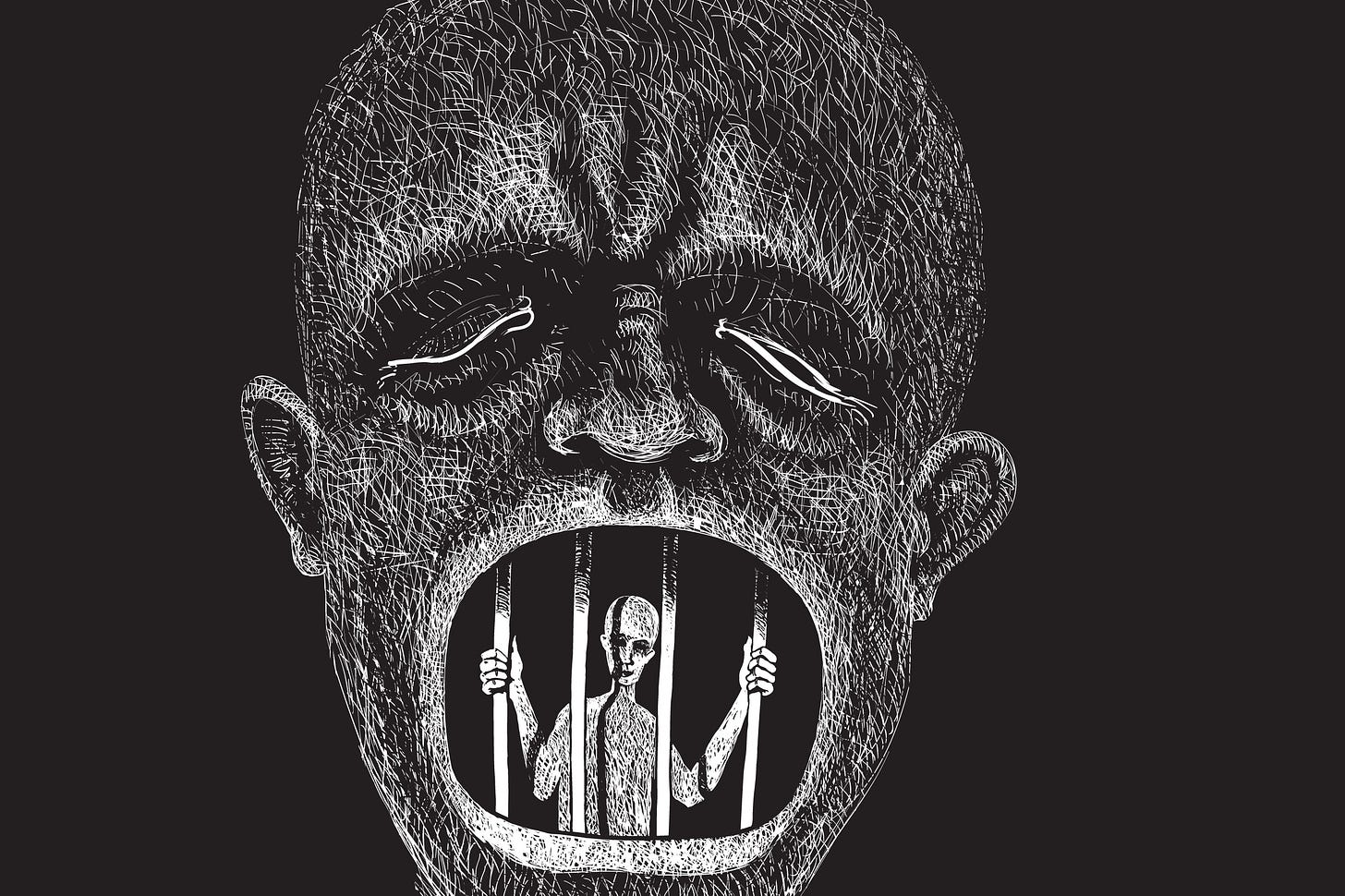

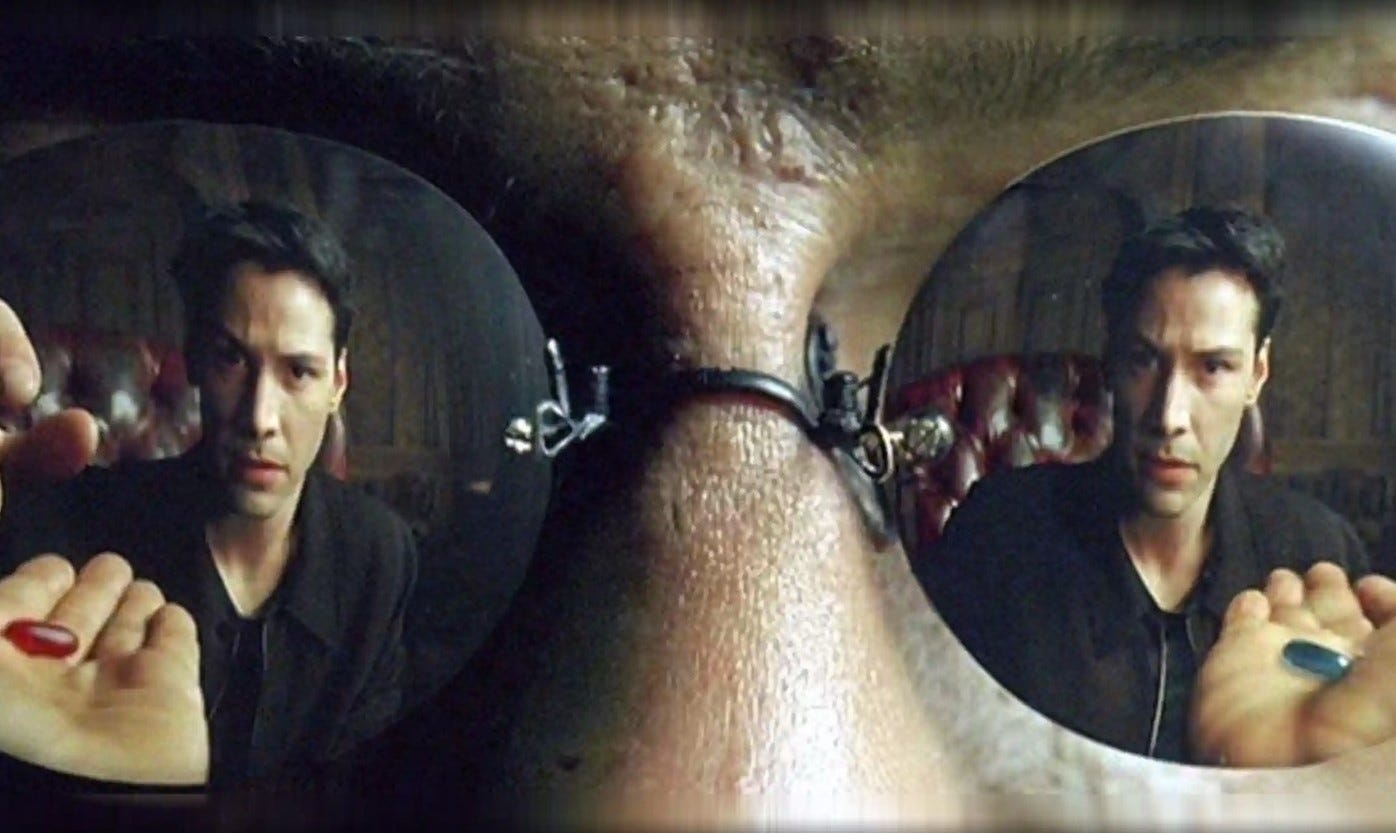

In Anarchy, State, and Utopia, the philosopher Robert Nozick posed the following now-famous thought experiment:

Suppose there were an experience machine that would give you any experience that you desired. Superduper neuropsychologists could stimulate your brain so that you would think and feel you were writing a great novel, or making a friend, or reading an interesting book. All the time you would be floating in a tank, with electrodes attached to your brain. Should you plug into this machine for life, preprogramming your life's experiences?

Nozick’s point was to expose the limitations of any purely hedonic conception of the good life. After all, if the summum bonum is simply to maximize pleasure and minimize pain, the experience machine sounds like a ticket to paradise. If all that really matters are enjoyable mental states, who cares if those states are divorced from anything happening in the real world?

Thanks for reading The Permanent Problem! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work. Nozick assumed that his readers would share his aversion to the experience machine, and that their reaction would reveal the shortcomings of the Benthamite view of happiness as nothing but sensation. He then offered some explanations as to why the experience machine is unappealing. “First,” he argued, “we want to do certain things, not just have the experience of doing them.” Furthermore, “we want to be a certain way, to be a certain type of person,” desires that cannot be fulfilled as “an indeterminate blob” in a tank. Finally, the experience machine can only offer us artificial simulations: “there is no actual contact with any deeper reality.” “Perhaps,” he concluded, “what we desire is to live (an active verb) ourselves, in contact with reality.”

I’m with Nozick on this one, but it turns out that not everybody has the same reaction. Consider this December 2021 tweet by Megan Fritts, a philosophy professor at University of Arkansas at Little Rock:

Just taught Nozick’s Experience Machine for the hundredth time. All but one student were immediately and unreservedly in favor of entering the machine for life. Never had that happen before, rather threw off my lesson plan!

… It’s always the dose that makes the poison, so at what point does choosing virtual experiences over real ones become dysfunctional — a hindrance to, rather than an enjoyable embellishment of, a fulfilling life? I’m not sure where that point lies, but I’m reasonably confident we’re now on the wrong side of it.

How we’ve harmed kids’ mental health by stopping them play

The central idea of my forthcoming book, The Anxious Generation, is that we have overprotected children in the real world, where they need a lot of free play and autonomy,while underprotecting them online, where they are not developmentally ready for much of what happens to them. …

The first fact is that over the past 5 decades or more we have seen, in the United States, a continuous and overall huge decline in children’s freedom to play or engage in any activities independent of direct adult monitoring and control. With every decade children have become less free to play, roam, and explore alone or with other children away from adults, less free to occupy public spaces without an adult guard, and less free to have a part-time job where they can demonstrate their capacity for responsible self-control. Among the causes of this change are a large increase in societal fears that children are in danger if not constantly guarded, a large increase in the time that children must spend in school and at schoolwork at home, and a large increase in the societal view that children’s time is best spent in adult-directed school-like activities, such as formal sports and lessons, even when not in school.

The second undisputed fact is that over these same decades, rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide among young people have increased enormously. Using data from standard clinical questionnaires administered to school-aged children over the decades, researchers have estimated that the rates of what we now call major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder increased by roughly 5- to 8-fold during the second half of the 20th century, and other measures indicate that they have continued to increase during the first two decades of the 21st century. …

Immediate effects of play and other independent activity on mental well-being.

Research, proving what should be obvious, shows that play is a direct source of children’s happiness. When children are asked to depict or describe activities that make them happy, they depict or describe scenes of play. There is also research showing that when children are allowed a little more play—such as when schools offer a little more recess—the kids become happier. Research also reveals that children consider play to be activity that they themselves initiate and control. If an adult is directing it, it’s not play. The joy of play is the joy of freedom from adult control. Other research reveals that the rates of emotional breakdowns and suicides among school-aged children decline markedly every summer when schools shut down and rise again when schools open. During the summer children have at least some more opportunity for independent activity than they do during the school year. There is also evidence that teens who have part-time jobs are happier than those who don’t, because of the sense of independence and confidence they gain from the job.

Long-term effects of play and other independent activity on mental well-being.

Beyond promoting immediate mental well-being, play and other independent activities build mental capacities and attitudes that foster future well-being. Research shows that people of all ages who have a strong internal locus of control (internal LOC), that is, a strong sense of being able to solve their own problems and take charge of their own lives, are much less likely to suffer from anxiety and depression than those with a weaker internal LOC. Obviously, however, to develop a strong internal LOC a person needs considerable experience of actually being in control, which is not possible if you are continuously being monitored and controlled by others.

Other research has assessed relationships between the amount of time children have to direct their own activities and psychological characteristics predictive of future mental health. Such research has revealed significant positive correlations between the amount of self-structured time (largely involving free play) young children have and (1) scores on tests of executive functioning (ability to create and follow through on a plan to solve a set of problems); (2) indices of emotional control and social ability; and (3) scores, 2 years later, on a measure of self-regulation.

Affirmative action for the 1 percent (and more for the 0.1 percent)

HT: David

The unbearable unutterability of Brexit

Just as critics predicted, Brexit has led to inflation, labor shortages, business closures and travel snafus. It has created supply chain problems that put the future of British car manufacturing in danger. Brexit has, in many cases, turned travel between Europe and the U.K. into a punishing ordeal. … British musicians are finding it hard to tour in Europe because of the costs and red tape associated with moving both people and equipment across borders, which Elton John called “crucifying.”

The U.K.’s Office for Budget and Responsibility estimates that leaving the E.U. has shaved 4 percent off Britain’s gross domestic product … All this pain and hassle has created an anti-Brexit majority in Britain. According to a YouGov poll released this week, 57 percent of Britons say the country was wrong to vote to leave the E.U., and a slight majority wants to rejoin it. Even Nigel Farage … told the BBC in May, “Brexit has failed.”

This mess was, of course, both predictable and predicted. That’s why I’ve been struck, visiting the U.K. this summer, by the curious political taboo against discussing how badly Brexit has gone, even among many who voted against it. Seven years ago, Brexit was an early augur of the revolt against cosmopolitanism that swept Donald Trump into power. (Trump even borrowed the “Mr. Brexit” moniker for himself.) Both enterprises — Britain’s divorce from the E.U. and Trump’s reign in the U.S. — turned out catastrophically. Both left their countries fatigued and depleted. But while America can’t stop talking about Trump, many in the U.K. can scarcely stand to think about Brexit.

You won’t believe what ChatGPT said next …

It was pretty good.

The Blues Brothers

I love the Blues Brothers film and must have seen it over ten times as an undergrad as it was on each Friday at Midnight at the Valhalla in Richmond with the front five or so rows reserved for people in full Blues Brothers’ gear. It’s a gem. Many years later I bought a cassette tape of some of their live performances, but I had never seen this. You probably have. It’s great.

A newsletter needs a puzzle

I think I did this in about 15 seconds. (But I would say that wouldn’t I?)

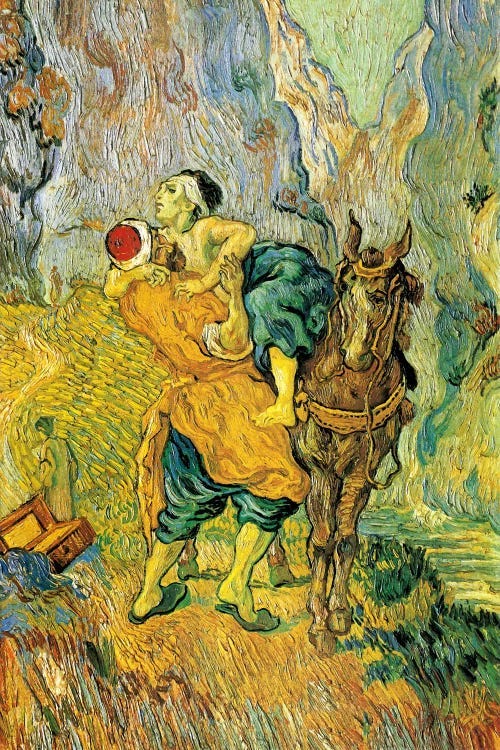

The Triumph of the Good Samaritan

An excellent article. The problem it discusses is a huge one — the ideologisation of our Christian heritage. It figures America as a stepping stone to human betterment, which is all very well — true no doubt, but even so, a sign of things to come in the essay. Unfortunately this was just a hint of the ridiculous final section which partakes of the great silicon valley trope.

Everything’s so busted, us bro’s will just have to start the whole thing again. And we’ll do it just like the founding fathers. As John Button used to say to me as he sent me into a Caucus committee meeting to represent him “Go get them Nick. Go get them for America”.

Oh well, four out of five sections are good — some excellent. The fifth section foreshadows a cult.

Living in a big West Coast town means becoming familiar with tent cities and the fights that come with them. What sparks it off is when homeless encampments annex formerly public parks—often with direction and oversight from activists—and make them functionally off-limits to the locals, especially in what were once “nice” areas. The sudden loss of space and threat of violent crime, along with open drug use and prostitution, tends to shock the locals out of complacency. The homeless crisis is easy to ignore until it spills out of its confined areas.

In these circumstances, the affected neighborhoods tended to rally in their own self-interest, organizing against threats of violence, property crime, and the seizure of public space. Whenever this happened, an array of full-time activists, as well as mobilizable students and sympathetic professionals, turned out to champion the cause of the tent cities. The language they favored was that of neighborly love. “Defend our neighbors without homes!” was the sort of thing I would hear them chant. On its face, it was the very same ideal I had heard preached at the little church. And yet, the fruits of it were entirely different.

The total absence of real communal ties was evident to me from the start. …

It was not until the experience of the little Byzantine church that I fully understood the difference. Both used a language of neighborly love and leaps of faith on others. But one operated on the basis of a compelling form of life. Their radical charity extended an open hand toward others with the intention of integrating them into their own functional pattern of life. They did not see charity as an open-ended license to parasitic behavior.

When members of the community fell out with each other, the practice of forgiveness was not intended to enable the behaviors at fault. Rather, forgiveness allowed people to move on from slights and return to baseline cooperation and affection with one another. It was not intended to facilitate destructive norms or people, particularly ones that threatened to undermine the community as a whole.

Moreover, the form of life practiced by the church community was both attractive and functional. As people embraced it, their lives improved in concrete ways. They took on roles of support and responsibility in their community and began to realize their own agency. They gave up destructive habits and formed healthy ones. Multiple categories of relationships—some egalitarian, and some not—existed to ensure moral correction, and the basic norms were clearly and explicitly taught by those with authority in the community. There was a way you ought to conduct yourself, a life you ought to live, and evil you ought to avoid. In extreme cases, that authority extended to initiating a formal censure through excommunication or barring a particularly destructive person from the space. …

The virtue of the Samaritan is not that he considered all men to be his neighbors, but that he himself took a leap of faith and acted as a neighbor to someone who was not yet one. The Samaritan’s act bore fruit, and he left the Hebrew he saved behind as a true neighbor, perhaps even a friend.

The momentary decision to show mercy is not, strictly speaking, a rational act. Rivals and enemies don’t merit such expectations. Any moment in which one shows mercy or offers the hand of cooperation to an enemy is a leap of faith. But charity itself has a rational character to it: by putting aside private advantages to work for the welfare of another, you offer a moment where they can start to do the same for you. That bond of reciprocal commitment to a common cause is the beating heart of every friendship, brotherhood, marriage, cult, war band, aristocracy, and other instance of society that has ever graced the earth. The initial moment where an open hand is extended makes it possible for a new “us” to emerge.

From The German Genius by Peter Watson

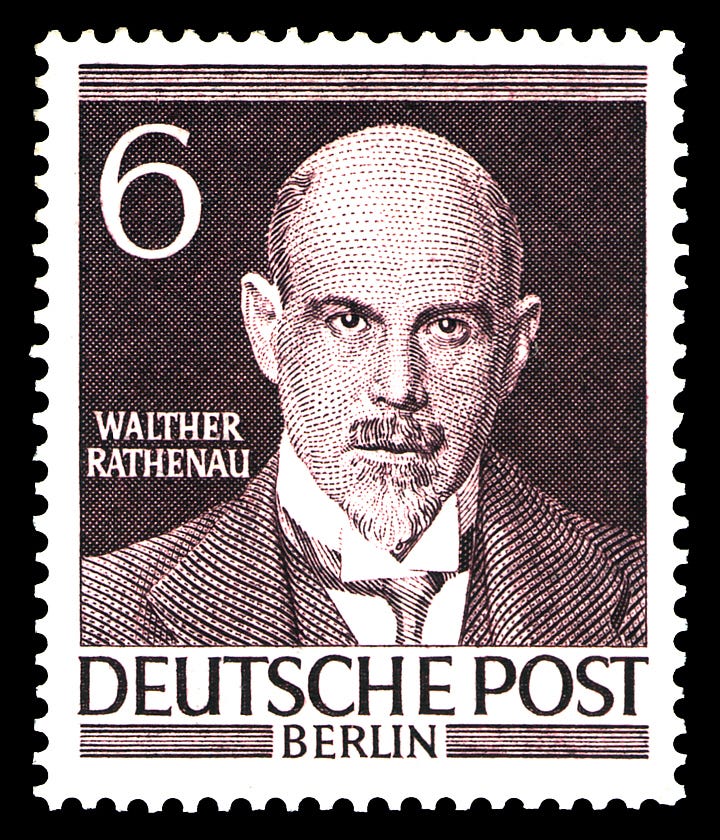

Walther Rathenau

Just as Daimler cars were the fruit of a father-and-son collaboration, so AEG, Germany’s other great engineering company, alongside Siemens, was developed by the father-and-son team of Emil and Walther Rathenau. In fact, Rathenau and Siemens, who at one stage were partners, form brackets to this section, emphasizing how intertwined German science, business, and politics were between the middle of the century and the First World War.2

Emil, born in Berlin in 1838, into a wealthy Jewish family, had bought himself a successful machine factory in the north of the city two years before Walther’s birth. Thus he had made one fortune by the time of the Paris Exhibition of 1881 when he saw Edison’s electric lightbulb. He snapped up Edison’s patents and two years later founded the Deutsche Edison-Gesellschaft (German Edison Company, or DEG). This seemed a clever move since he did so in collaboration with his greatest potential customer, Siemens. In fact, in its early years DEG was beset with technical and legal problems (over patents, mainly) and because of this the company was eventually transformed into the Allgemeine Elektrizitätgesellschaft (German General Electric Company, or AEG). The links with Siemens were dissolved and only in 1894 was Emil Rathenau able to begin to turn his firm into the biggest electrotechnical giant in Germany.

The Rathenau family was Jewish only in name. Mathilde Rathenau, the daughter of a Frankfurt banker, took care to give her children (two boys and a girl) a good education in music, painting, poetry, and the classics of literature. For her, business wasn’t everything. Walther never formally accepted Christianity, but he did acknowledge the divinity of Jesus and, in a magistrate’s court in Berlin in 1895, disassociated himself from his former “Mosaic belief.” All his life he was sensitive to the second-class status of Jews in Germany, yet at the same time he advocated assimilation and hoped for equality. Like many other Jews, he regarded himself as a German: everything else was of lesser significance.

Having a PhD (from Strasbourg), Rathenau kept up with scientific developments—the behavior of metals, electrolysis, hydroelectric power—but he was always more interested in industrial organization, business strategy, and its links to politics, rather than the day-to-day running of companies like AEG. This made him ideal board material, and Rathenau’s real significance is that he formed part of that generation of industrialists—Krupp, Stinnes, and Thyssen were others—who began to rival the army officers, diplomats, and professors at the top of the status ladder, though the rising prestige of the industrialists was opposed by a fierce anticapitalist and anti-industrial feeling in some quarters, who saw industrial power as the main cause of human misery. Although many realized that the Industriestaat was replacing the Agrarstaat, industrialists still found it difficult to progress politically and Rathenau in particular found this frustrating. Yet Germany did change fundamentally from the 1890s onward, when industry replaced agriculture, forestry, and fishing as the mainstay of the country’s GDP and when more workers were employed in industry than in agriculture, and more people lived in cities than in small towns and villages.

Unlike his critics, Rathenau was convinced that industrialization and capitalism were the only secure foundations for a powerful modern state, and he also felt that the German Empire had the long-term edge over Britain, because it also had a strong agricultural sector. He was similarly convinced of Britain’s industrial decline, for which he blamed the trade unions, the poor level of training for engineers, and weak management. He did not believe, however, that the industrial state was an end in itself. “He saw industrial domination as a transitory phase to achieve a greater ‘spiritualised’ period in human history.” He was led in this way to a relatively crude social Darwinism allied with some of Gobineau’s racial beliefs. Rathenau felt that, eventually, the northern European middle classes—people like himself—would come to dominate the world. Educated businessmen were the new aristocracy, who would know where to lead their fellow citizens to the higher, post-material spiritual level. Continuous industrialization, he was convinced, must be accompanied “by ethical achievement.” He was therefore in favor of heavy taxes for the rich both in life and in death—he wanted to see an “uncompromising” inheritance tax and he went so far as to advocate the “abolition of luxury.” “Distribution of property,” he wrote, “is not a private affair, any more than is the right to consume.” And he argued that “richness should be replaced by prosperity which in turn is based on creativity and responsibility for one’s work or one’s own society.” Workers should have a say in management. However, as Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann has pointed out, “there is no evidence to suggest that Rathenau pursued a markedly different line towards his own AEG employees from that of other industrialists towards theirs.” He thought that better working conditions would increase productivity.

His importance lay in the clarity with which he saw—and described—what was happening in Germany, how the dynamics of modern prosperity were shaped by science and industry and how the country’s traditional elite was failing to adapt. If there was a whiff of sanctimony about his stance, that too was revealing. He was better at identifying problems than at finding solutions.

Erich Maria Remarque

In Chapter 29, we saw that the experiences of men in modern technological warfare in the Great War were so extreme as to bring about a whole new set of psychological problems among the admittedly brave men in the trenches. Do these subconscious anxieties account for the delay in the appearance of so many war-related novels, a delay that occurred on both sides? Ford Maddox Ford’s No More Parades was published in 1925, Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, about an injured war veteran, appeared in 1926, while Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, was not released until 1930. Between these last two, in 1928, there was the most successful of them all, at any rate commercially—Im Westen Nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front), by Erich Maria Remarque.

Christine Barker and R. W. Last argue that All Quiet is one of the most important books of the twentieth century, but neither one of the greatest, nor yet the best work of Remarque himself. Born in 1898 in Osnabrück, Remarque was dogged by controversy, in particular concerning what he actually did in World War I and whether he won the medals he said he did. He was never stationed at the Front, but it appears he did perform heroically, helping carry wounded soldiers out of danger.

After the war he began writing short stories and sketches, moved to Berlin in 1925, and worked as a journalist on Sport im Bild (Sport in Pictures). All Quiet was written two years later, serialized in the Vossische Zeitung at the end of 1928 (eleven other papers turned it down) and appeared between hard covers in January 1929, where its overnight success altered Remarque’s life forever.

The novel tells the story of a class of young men who are sent to the war, are much depleted, and carry on the fight with older, more experienced men. There are many passages when the men/boys contemplate life back home, and the world of love which—for most of them—hasn’t really opened up yet. The claustrophobia of war gradually closes in on the men as, out of the original eight school friends, only one remains. Remarque explores the different ways that the men/boys are alienated, as they try to grasp whether they are cowards or heroes, individuals or comrades-in-arms, proud combatants, or ashamed and disappointed. They come to realize how being in such a terrible war has cut them off from people who will never have this experience. Although the book has it share of clichés, some of the images have become famous, as that of the dying cigarette hissing on the lips of its already-dead owner.

All Quiet was bleak, very bleak, but it stimulated a boom in war novels and provoked enormous controversy, for its writing style, its “defeatism,” and its unpatriotic depiction of war. About a year after publication, by which time the book had sold close to a million copies and been translated (or was in the course of translation) into several languages, the Nazis turned on Remarque, making the book into a political issue because he had challenged the myth of individual heroism in armed conflict. The campaign was spearheaded by Goebbels himself and began when Hitler Youth disrupted the screening of the American film of the book in 1930.

Remarque left Germany and eventually reached America. His bank account was seized, but he had wisely already moved most of his money, together with his collection of Impressionist and post-Impressionist paintings—Cézanne, van Gogh, Degas, Renoir. All Quiet was burned in the notorious book-burning in Berlin in May 1933, but in some ways Remarque had the last laugh. In America he went to Hollywood, where he formed firm friendships with Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo, Charlie Chaplin, Cole Porter, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway. He even acquired the title “King of Hollywood” because of the number of films made from his books, including The Road Back, Three Comrades, A Time to Love and a Time to Die, Heaven Has No Favorites, and Shadows in Paradise. For Remarque, in these books nothing endures—each individual is alone, there will never be any clear answers to the problems and mysteries that trouble us; life may have its moments of extreme beauty and even happiness, but that is all they are, moments. Remarque said he believed that human nature in Germany was especially bleak and that it had been so since Goethe and Faust.

Nicholas: More interesting reading and things to mull over.

Erich Maria Remarque's books were (several - including All Quiet, The Road Back, Three Comrades, The Complete Works of Erich M Remarque) first translated into English by his Australian contemporary Arthur Wesley Wheen - from Sydney - a Great War combatant himself. His great nephew in Sydney - and somewhat guardian of his history - himself a poet, writer and translator (Bahasa, Spanish, tieng Viet - early work/interest in the latter 1960s in PNG) is Ian Campbell. I have just copied your piece through to him. Jim