Extra edition: On the disintegration of American democracy: how far can it go?

And other things that overraneth my cup this week

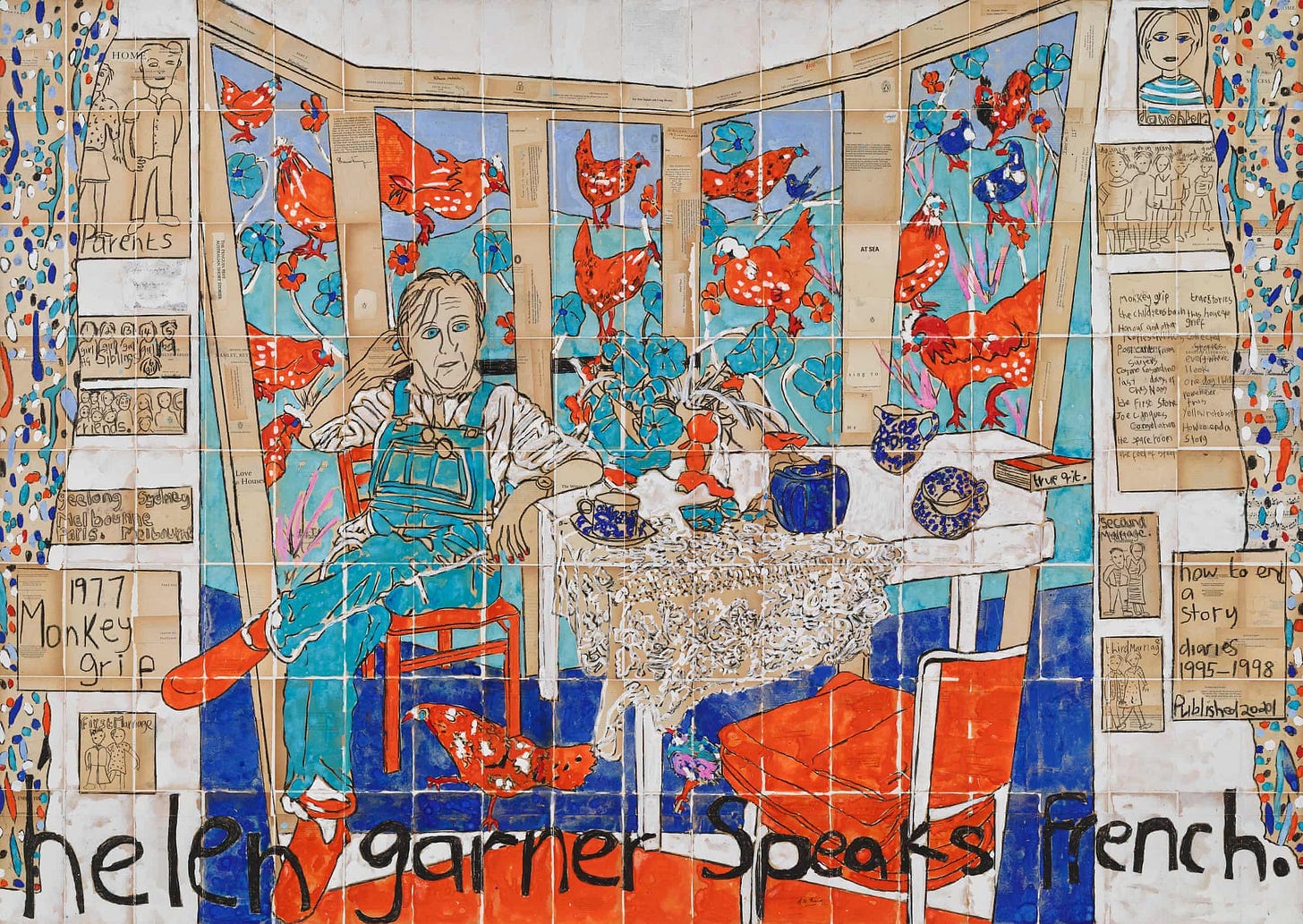

In Praise of Helen Garner

“[T]here is an Australia of the spirit, submerged and not very articulate … sardonic, idealist, tongue-tied perhaps. It is the Australia of all who truly belong here, and it has something to contribute to the world—not emphatically in the arts as yet, but in action and ideas for the egalitarian democracy that must underpin all civilised societies in the future.”

— Vance Palmer, 1942

I’ve always liked Helen Garner’s writing. It’s very good. But it’s deceptively good. And the deception isn’t the artist’s deception of passing off mediocre work as better than it is, but rather the reverse. Its ordinariness evades our usual early-warning systems for sensing the presence of excellence.

Reading an international profile of her, I realised I’d played a very Australian trick on myself: not taking our own cultural contributions as seriously as I might. Everything comes from a point of view. And—here’s a bold claim, even if it could be wrong—every point of view can serve as a base camp for an ascent on the summit.

Even that isn’t quite right, because surely one point of Garner’s style, is to deny any sharp divide between serious and non-serious art. What struck me, thanks to the Guardian profile of Garner, is how Australian this is. Building her style around the Australian culture’s aversion to pomposity, is a great gift to us.

It’s so pronounced that our national aversion to pomp can sometimes turn into its own kind of stagey, even pompous, mateyness. Bob Hawke turned that into political charisma; John Howard did the same, though less compellingly. It’s why our sporting champions, fresh from exhibiting their world-beating skills on the field then become magnificently, world beatingly tongue-tied on the victory dais, even more so than New Zealanders.

And it’s why Australia’s only unique contribution to political oratory so far is Paul Keating’s demotic schoolyard anti-oratory. Shy of declaring its higher aspirations, it made them implicit — and partisan — the possession of the left but not the right. Anyway, this passage is where the penny dropped for me about my own Aussie underestimation of Garner:

Her relentless self-interrogation is a way of dismantling the idea of the writer as someone special, separate or aloof. She reserves a particular disdain for the author who thinks himself superior. She once watched Melvyn Bragg interview Martin Amis. ‘If you don’t think you’re the best, you’re not really doing it,’ said Amis. Garner: ‘I wanted to dong him with a bat.’

So thanks, Helen! Below are some more extracts from the Guardian profile (but I suggest you click through to the whole thing) and a recent interview.

Garner’s longtime hero, the American nonfiction author and New Yorker journalist Janet Malcolm, would have relished scrutinising the terms of this deal. I doubt she’d have thought it fair. In Malcolm’s view, the writer of nonfiction has an exploitative power over their subject. No matter what high-minded justifications the writer claims for their work, such writing is almost always an act of “treachery”, morally indefensible, in which the subject is the victim, duped to furnish a story. Even if a writer like Garner exposes and punishes themselves as much as anyone else, it is still her version and her choice alone to publish.

Malcolm’s influence is detectable throughout Garner’s nonfiction, most obviously in the lure of the courtroom and her interest in criminal psychology. (Garner is fond of saying that “as soon as a dead body appeared in my work, the windows and doors opened”.) But Malcolm also revealed a new way of writing. When Garner read The Silent Woman, Malcolm’s book on Sylvia Plath and her biographers, published in 1994, she was struck by Malcolm’s fearlessness and how she used psychoanalytic methods to locate meaning in the way someone cooked a lasagne or decorated their house. Garner, who had psychoanalytic psychotherapy during her third marriage, thought: “OK, well, I’m going to let it rip too.” She began to include observations in her books that she would previously have dismissed as illegitimate, the micro-interactions that revealed more about a person than their words. In an interview with a professor for The First Stone, Garner kept helping herself to biscuits in a jar on the table until he moved the jar out of her reach. She found the moment funny and full of subtle meaning, the way it communicated the power struggle between her and her subject. Under Malcolm’s influence, it became material.

Garner met Malcolm once in the early 90s, at a party while she was teaching in New York. She found her hero in the basement, sitting on a chair with a baby on her lap. The way the baby was positioned made it look as if Malcolm and the baby’s heads were stacked on top of each other, like some kind of surrealist sculpture. Garner burst out laughing, then awkwardly introduced herself. “I didn’t know what to say,” she recalled. She wanted to say thank you, and that she’d learned so much from reading her, but never got the chance, “because the door bursts open and in strides this big noisy New York intellectual woman whose name I’ve forgotten and says: ‘Darling Janet!’, and blows the whole thing out of the water, so I just kind of turned and went into a slump.”Garner tells the story in typical fashion: comic, self-deprecating, describing herself at the edges of grandeur but excluded from its inner circle. She encountered Malcolm more directly on the page. Malcolm had unfavourably reviewed The First Stone in the New Yorker. Garner hadn’t minded, delighted that her idol had even read the book. Years later, she in turn reviewed Malcolm’s book Iphigenia in Forest Hills, about a murder trial. “I thought: ‘Gee this is a dog’s dinner up the front.’” Garner briefly wrestled with how honest to be in her review, then said precisely what she thought. Afterwards, she received an email from Malcolm, thanking her. “And I thought, that’s big of her. Some woman comes up from Australia and says your book’s a dog’s dinner, and she took it right on the chin.”

Garner’s conversational style is remote from Malcolm’s cool distance. (It is hard to imagine Malcolm using the phrase “dong him with a bat”.) “I haven’t got any theory you see. That’s the difference between her and me. She was way more highly educated than I am.” Yet it is Garner’s directness, unburdened by abstraction, that gives her work its power. In This House of Grief, Garner recounts the trial of Robert Farquharson, a man charged with killing his three sons by driving them into a lake and letting them drown in the car while he escaped. In court, Garner is open to every emotional reverberation. She notes the muffled screams of the boys’ mother, the traumatised expressions of the jury, the abject slump of Farquharson’s shoulders. She does not absent herself from the material – she is stricken by it. She has often said that in court she discovered the work she felt she was born to do: her observational precision and acute sensitivity working in concert. In one of our conversations, she recalled how Bail would tell her she cared only about feelings. “And I thought: ‘Well, what else is there?’” …

Garner is an extrovert, thirsty for interaction. She starts up conversations with strangers as she travels around Melbourne. She likes to play the ukulele, to dance, to turn up music loud. [Tim] Winton told me about a “classic day with HG” – they attended church, mocked the minister, wept at the altar, then went home where Garner lay on the bed and declared that his toddler son had “an arse like a porn star!” His favourite photo of Garner captures her laughing. She writes laughter constantly in her work: pissing herself, doubled over, tears pouring, laughing her head off. One of her many frustrations with Bail was his inability to understand what she called the moral value of fun. To her friends, it was obvious she was losing essential parts of herself in the relationship. “There were some dark years for Helen,” said Winton. …

In the diaries, when Garner discovers Bail is having an affair, she goes berserk (her word). She hurls soup, coffee cups and butter around the kitchen, cuts up an Armani scarf he’d given her and tries to destroy a blue straw hat belonging to Bail’s lover by punching it in the crown, “but it keeps popping back into shape”. Then she takes the proof copy of “his fucking novel” and repeatedly stabs it with his Mont Blanc fountain pen until the pen’s nib breaks and twists into a golden knot. She squashes his cigars into some beetroot soup in the sink and then finishes the job on the hat, cutting it into strips and putting one in each of “his big ugly black suede shoes”. She leaves him a note: “Don’t you know that being lied to makes people crazy?”

The violence was wild and uncontrolled, but it is written and edited into the tightest prose. Published 20 years after the events, the diaries are like a mafia revenge killing, held back until the target could not possibly suspect he was still at risk. …

When the final part of the diaries came out in Australia in 2021, Garner was amazed by how many women emailed to thank her and to say how it reminded them of their own marriage, and how many men told her they could see themselves in Bail. She never heard from Bail himself. In her view, his response came in the form of a memoir, He., published in 2021. “He dismissed me in a very high-handed manner. I think I only took up about 14 lines,” she said. One of these lines is: “After 10 years the gradual then abrupt ending of the second marriage.” She found it funny. “I thought, OK, he put me in my place. It was a passing phase instead of a complete collapse of civilisation the way I presented it.”

Bail tells it differently. “The memoir He. was not written in response to Helen’s diaries,” he told me in an email. “It never occurred to me. I haven’t read them. They are Helen’s own view of our time together. I didn’t imagine the last volume would be published while so many of the people were still alive, including me.”

And see the interview with Helen Garner below: just before Heaviosity Half-hour

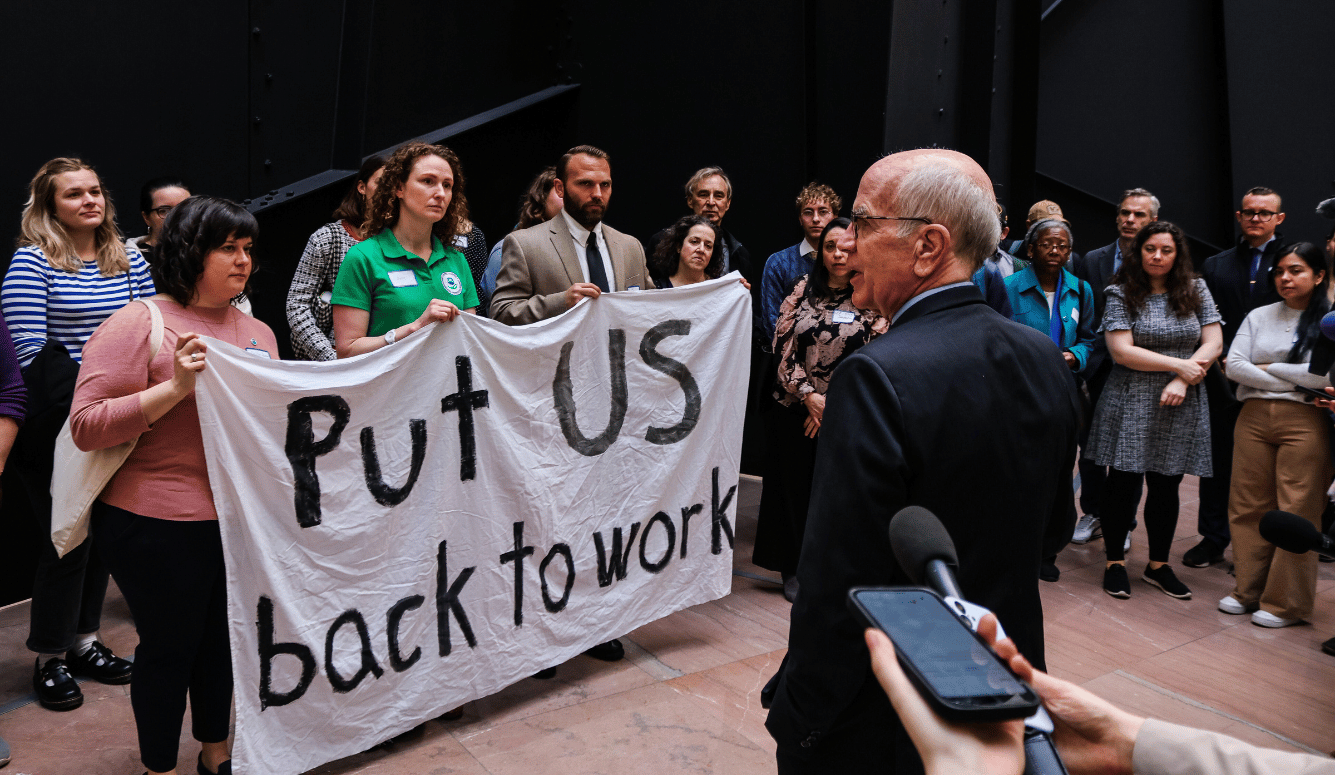

On the degradation of American democracy

The case for short-term optimism, long-term pessimism

A deeper analysis than lots that are around. Though Nathan attributes a lot of the problem he discusses to the lack of an opposition — what his argument put me in mind of was an argument in Ezra Klein’s Why We’re Polarised which I extracted in yesterday’s Heaviosity Half-hour. The argument is that congressional systems have an inherent instability built into them because the way they separate legislative and executive powers powers creates different nodes of power which can become intransigent.

Separation, or at least devolution of powers is fundamental to stable government, but in Westminster systems, when there’s a war between the executive and the legislature the legislature can, in extremis, simply get itself a new executive. You can’t under a congressional system.

The big story tonight... is that Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer backed down and agreed to help the Republicans pass a Continuing Resolution... despite the fact that Democrats were completely locked out of negotiating this and that it seems sort of weird to pass an appropriations bill right now when Elon Musk and Donald Trump are quite openly refusing to obey congressional appropriations bills and boasting that they will continue to do so.

Schumer’s arguments are predictable, reasonable, and I think wrong... A government shutdown now would be Very Bad, but helping Republicans pass a budget under these circumstances is a de facto admission that what they’re doing... is within the bounds of acceptable politics. I don’t want to argue about that right now though. If you’re on social media... you’re aware.

I do want to talk about why I think he, and the Democratic Party is making this mistake... I have... described my position on contemporary politics as "short-term optimist, long-term pessimist." I do not think that what Trump is doing... is likely to result in a consolidated authoritarian regime. I think he is going to create a dysfunctional Federal government, a broken economy, and a very angry country, and the result is quite likely to Democratic victories in the midterm election of 2026 and the presidential election of 2028. But that doesn’t mean they’re going to be able to reverse what’s being done now... The Trump Administration is... creating the bounds of the possible for the foreseeable future—as is demonstrated by the fact that Democrats are about to sign off on a budgetary process that they were denouncing as unconstitutional yesterday.

If you’re on... social media... you’ve probably seen the various debates... over the Democratic response... A very common fracture line has been "Democrats are savvy, smart politicians playing the long game" versus "Democrats are feckless cowards afraid to fight." I would like to propose a compromise position... Democrats are savvy, smart politicians, and that’s exactly why they’re going to fail to reverse or prevent the ongoing dismantling of the Federal government.

Democrats are, generally, good politicians... Chuck Schumer has been in the Senate since 1999, and he was in the House of Representatives for twenty years before that. As one of his constituents, I can assure you that he is notorious for being willing to show up literally anywhere to do anything... But what does it mean to be a good politician? It means knowing how to play the rules of the game... I think Chuck Schumer is very good at all that. I don’t think he’s very good at leading a popular movement to restore constitutional government. Unfortunately, that’s what we need right now.

What Musk and Trump have been doing since inauguration is a coup d’etat... justified by legal theories that would amount to overturning several hundred years of precedent. Stopping it... is going to require strong leadership, and the political will to fight battles that nobody wanted to or thought we had to fight. Unfortunately, the way American politics is structured makes it very hard for that to happen.

The Democratic Party has no leader... Chuck Schumer does not speak for the Democratic Party. Neither does Hakeem Jeffries... or Ken Martin... The DNC raises money... but it does not have any kind of authority over the fifty individual state parties... If it feels like nobody’s in charge, that’s because they aren’t.

There’s no such thing as the Democratic Party... There is nobody who can enforce ballot access, who can control access to funds, or who can determine who gets to run under the label of "Democrat" or "Republican."... Congress has been ceding its authority for decades now... the Senate has imposed a de facto super-majority requirement that has made normal legislating almost impossible... We’ve had government shutdowns in 1995, 1995-1996, 2013, and 2018-2019, and legislating by brinkmanship has become normalized. The result has been more and more power being appropriated by the other two branches of government... It is a symptom of this that Congressional Democrats... are waiting for the courts to tell them if it’s OK or not.

The Democrats are a very, very big and unwieldy tent... educational and cultural polarization has been whittling down the Democratic paths for victory for the last decade... 2024 showed ominous signs that we may be losing urban working-class voters too... For Democrats to win increasingly means appealing to a lot of different types of people in a lot of different places... The result is... an attempt to satisfy everybody that satisfies nobody.

American political economy is broken. It is really hard to get anything done in America, and specifically in Democratic-governed states... The metastization of process means that even minor improvements or updates can take many years and dozens of lawsuits... The result of this is that politicians who are good at navigating these sorts of systems... are not necessarily good at dramatic action. Everything takes forever—until it doesn’t.

We don’t have an Opposition Media. There is simply no left-wing or liberal equivalent to the right-wing media sphere... We need it. Demanding action from elected officials is useless unless we are able to mobilize public opinion to support them.

The decision whether or not to support the Continuing Resolution is... less important than the broader structural factors that created the current party... The Democrats are a conservative party, in the small-c sense of the word, trying to preserve the 20th century constitutional order. That’s a goal I agree with. But I think it might be too late.

Right now, the executive branch of the United States has appropriated a completely unprecedented level of power to itself... I do not believe these are developments that will simply be rolled back of their own volition... The question is not if the country is going to be fundamentally different in four years, it’s how.

Bernie’s not having it

But David Brooks is …

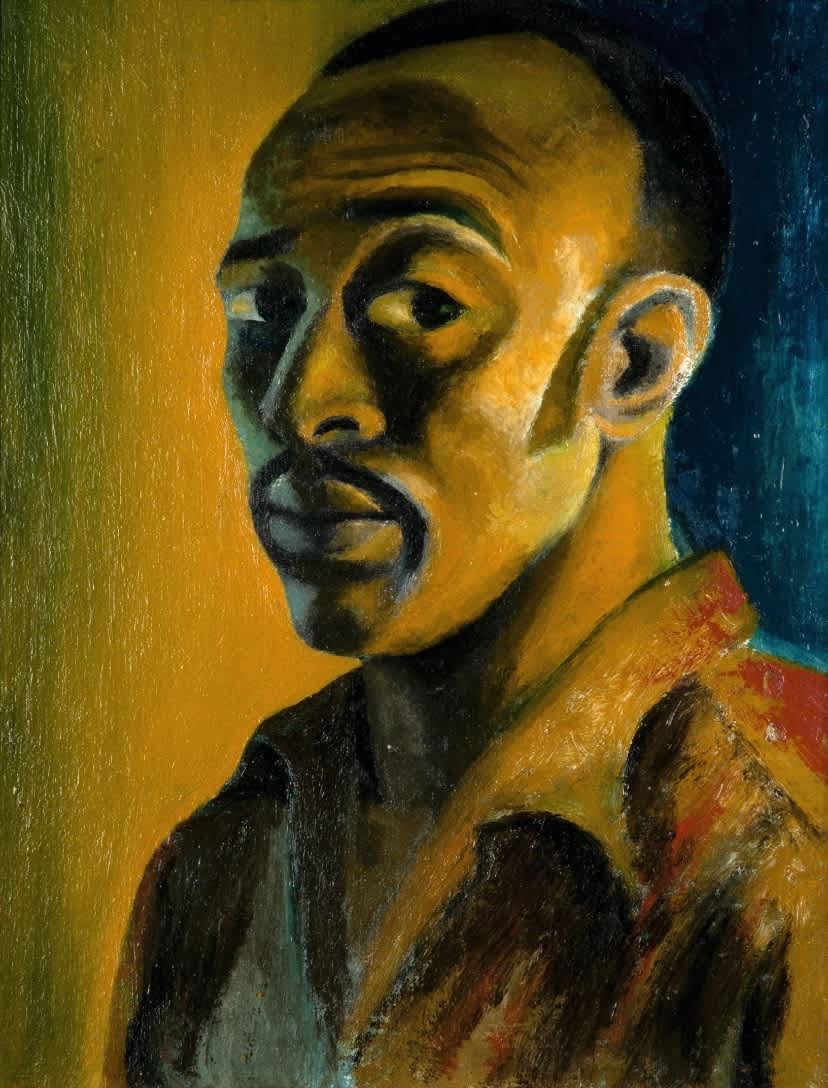

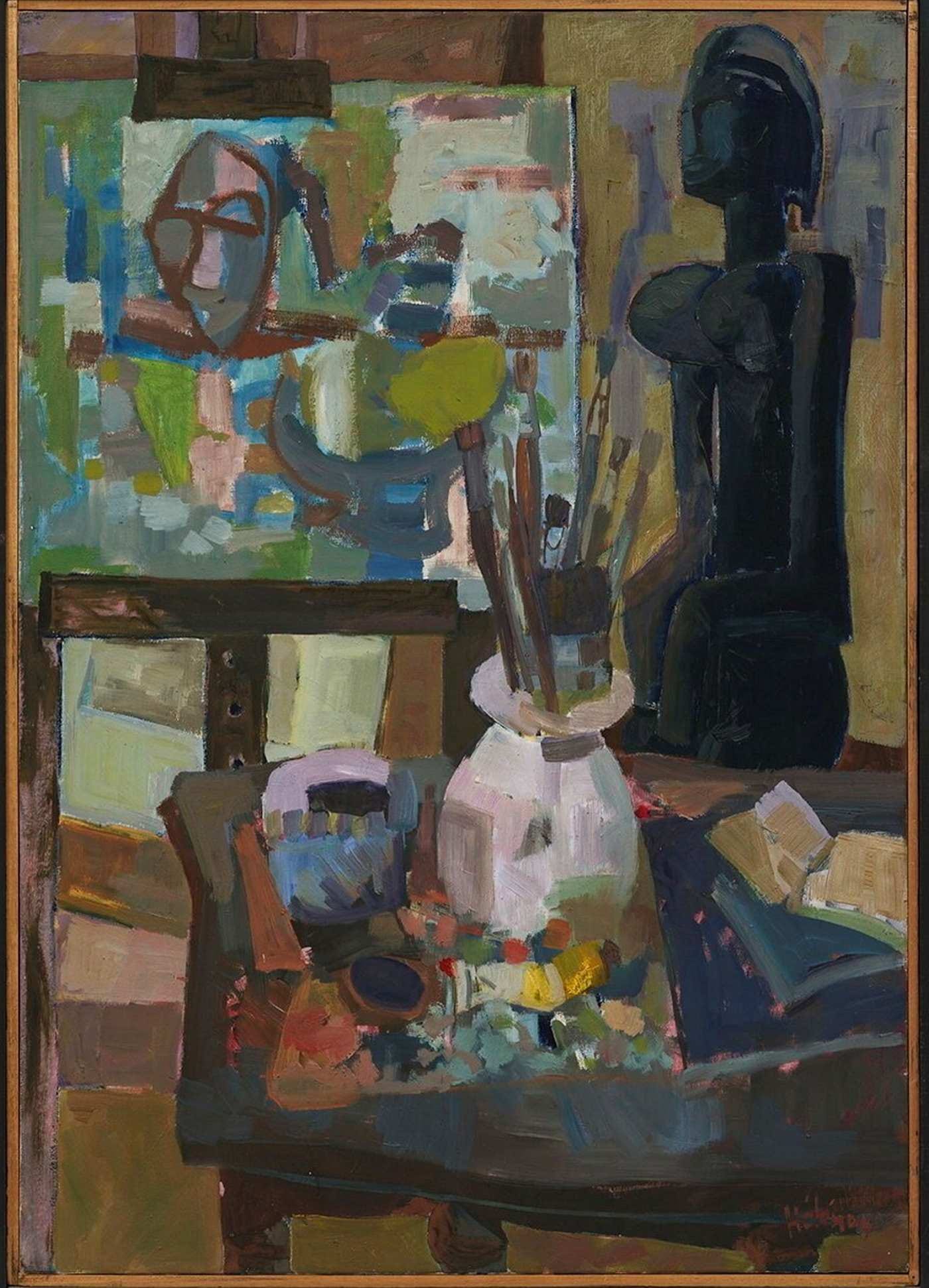

Who knew? Nigerian modern art

From a special feature in the FT:

When Ayo Adeyinka, founder and director of London-based Tafeta gallery, visited the Venice Biennale last year, he was thrilled. Brazilian curator Adriano Pedrosa’s exhibition Foreigners Everywhere promised to “question the boundaries and definitions of modernism”. “I thought there would be a bit of a look-in for the global south,” Adeyinka says. “I counted between the Giardini and the Arsenale at least seven 20th-century African artists we have shown in the past.” For all seven — including the pioneering Nigerian sculptor and painter Ben Enwonwu; Uzo Egonu, a painter and printmaker who moved to Britain from Nigeria in 1945; and the seminal teacher, painter, sculptor and illustrator Uche Okeke — it was the first time their work had ever featured at the Biennale. African modernism’s overdue recognition may have also reached the art market.

At the TEFAF fair in Maastricht, Tafeta’s main presentation (in the company of the gallery’s contemporary stars such as Yinka Shonibare and Nelson Makamo) is composed of 20th-century African artists. Tefaf has always shown classical African art, alongside the Dutch old masters, Asian antiquities and European fine and decorative arts for which the fair is famous. But those artists who initiated the conversation between Africa’s past and present, and between art movements prevalent in Europe and those indigenous to the African continent, in the context of nation-building and independence movements, have largely been missing. Adeyinka’s presentation seeks to rectify that.

Meanwhile at TEFAF fair in Maastricht

This TEFAF seems to be a big deal. Here’s D’Lan’s effort.

Andrew Sullivan on the new McCarthyite Chill

It’s gratifying to watch genuine conservatives join the fight against a lawless government, even though it’s on their side of the ideological aisle. Here’s Andrew Sullivan.

For those of us who have been worried about the erosion of free speech and discourse on American campuses, it is hard to think of a more chilling scene than this one, as reported in the NYT:

Days after immigration officers arrested a prominent pro-Palestinian campus activist, administrators at Columbia University gathered students and faculty from the journalism school and issued a warning ... “If you have a social media page, make sure it is not filled with commentary on the Middle East,” [Stuart Karle, a First Amendment lawyer] told the gathering ... When a Palestinian student objected, the journalism school’s dean, Jelani Cobb, was more direct about the school’s inability to defend international students from federal prosecution. “Nobody can protect you,” Mr. Cobb said. “These are dangerous times.”

It’s important to note that this is not about protection from woke professors or ideologically captured deans. It’s protection from direct surveillance by the federal government. The Trump administration has launched a massive, all-of-government, AI-assisted program called “Catch and Revoke,” which will scan every social media comment and anything online they can use to flush out any noncitizen who might be seen as anti-Semitic or anti-Zionist or anti-Israel or indeed just getting on Marco Rubio’s wrong side.

Mahmoud Khalil, a green card holder, has not been accused of a crime. And that is the point. A White House official explained: “The allegation here is not that [Khalil] was breaking the law.” A DHS spokesman elaborated to NPR:

“We’ve invited and allowed the student to come into the country, and he’s put himself in the middle of the process of basically pro-Palestinian activity. And at this point, like I said, the Secretary of State can review his visa process at any point and revoke it.”

“Pro-Palestinian activity” is the reason. The DHS document citing the law being used against Khalil — and thereby potentially every other noncitizen, including green card holders — has this legal formula:

[T]he Secretary of State has reasonable ground to believe that your presence or activities in the United States would have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States.

This is “the first arrest of many to come,” says Trump. DHS is already searching dorm rooms. Note the astonishing breadth of this legal formula. You could, for example, be a Ukrainian exile who furiously opposes the Trump administration’s new policy toward Russia. Under the Rubio standard, if you do not have citizenship, merely expressing your views in a way that jeopardizes US foreign policy interests is now a deportable offense. The Trump administration, unless a court stops them, has effectively removed the First Amendment from tens of millions of inhabitants of this country.

It’s actually worse: if you merely potentially could say such a thing, you can be deported for a pre-crime, or rather pre-noncrime. Every noncitizen in the US now has to watch what they say about foreign policy — or else. You may have just arrived from Putin’s Russia, and are now being told by Trump: don’t think you now have free speech just because you’re in America. The US government is monitoring your every word and can deport you if you say the wrong thing. You have to wait until you’re a citizen to be free.

If the law seems McCarthyite, that’s because it was passed in 1952 and aimed specifically at Holocaust survivors from Eastern Europe suspected of communist sympathies. According to historian David Nasaw in The Last Million, “suspected Communists were denied visas while untold numbers of antisemites, Nazi collaborators, and war criminals gained entrance to the United States.” It is one of the sublime ironies of this that the ADL now supports a law that once persecuted Holocaust survivors. Back in 1950s, the ADL called it “the worst kind of legislation, discriminatory and abusive of American concepts and ideals.” Now that the ADL can use the law to go after its foes, it’s fine. …

Can the Trump administration win this fight? I suspect they can. Rubio says he intends to deport any noncitizen who merely “supports Hamas” — not materially supports, but just supports Hamas — and not just in the past, but in the future.

But they seem to believe a visa is the same as a green card. JD Vance — who lectured Europeans on free speech online, while his own administration was using AI to police the web for dissent! — said on Fox that a green card holder “doesn’t have an indefinite right to stay in America.” The formal name for a green card is “Legal Permanent Resident”, Mr Vice President, not Legal Provisional Resident. They enter the US in the citizen line. And until now, every applicant for a green card has waited for that moment of relief when it’s finally granted, the knowledge that now you are safe and here for good. It remains one of the best days of my own life. Vance just stripped all of that away from all of us. Probably because, like the rest of these incompetent thugs, he doesn’t know what he’s talking about, and doesn’t much care. …

As for all those brave center-right defenders of free speech on campus these last few years? Just see if they are condemning this. And if they aren’t, never take them seriously on this subject again.

Another right winger against lawless, lying idiocy

Likewise in Quillette

R. Shep Melnick on “The Political Foundations of the DOGE Scam”.

The Trump/Musk administration’s approach to cutting costs makes good political sense in the short-run. But from a longer-run governing perspective, it is a recipe for disaster.

In 1968, public-opinion scholars Lloyd Free and Hadley Cantril published The Political Beliefs of Americans, in which they provide extensive evidence that Americans are “ideologically conservative” but “operationally liberal.” By the former, they meant that American voters are distrustful of centralised and bureaucratic government. They don’t like regulation or taxation (who does?). In the abstract, therefore, they prefer smaller government with fewer responsibilities to larger government with more benefits.

At the same time, Free and Cantril noted, Americans like the benefits, services, and protections provided by federal, state, and local governments. Only a tiny percentage of the public wants to cut spending on Social Security, healthcare, education, environmental protection, veterans’ programs, infrastructure, or assistance to needy children. Indeed, a majority usually want to spend even more on these programs. Over the past several decades, poll after poll has confirmed this. So has congressional politics. When Republicans have proposed major cuts in these programs, they have faced retribution at the next election.…

So, rather than use the congressional budget process to cut spending on popular programs (as the Reagan administration did in 1981–82), the Trump/Musk administration has mounted a spectacular—and in many instances illegal—assault on the federal bureaucracy. Their strategy is to attack the bureaucracy, but not the benefits and services it provides. …

One of the leading ironies of the DOGE attack on “waste, fraud, and abuse” is that it has targeted so many offices whose main job is to improve government performance. That is what the inspectors general in various departments and agencies do, yet they were among the first targets of this administration. Later, the administration eliminated a small office in the General Services Administration devoted to improving government websites. Cutting thousands of positions at the IRS will mean less effective enforcement of the tax code, less revenue, and an even larger deficit.

Identifying and eliminating waste, fraud, and inefficiency is essential work, but it requires detailed knowledge of government programs, and it seldom discovers large savings in any one program. That is why the blunderbuss DOGE attack has produced such wildly inaccurate accounts of its savings and so many spurious claims about misspent public funds.

The appeal of attacking an unpopular government bureaucracy rather than popular government programs is readily apparent. The big question is how soon the degradation of the former will lead to a reduction in the quality of the latter. The long-term costs of reduction in support for medical research are immense; the short-term costs are nearly invisible. This summer, families who visit our spectacular National Parks might observe the consequences of inadequate staffing; it will be harder for them to see what happens when our National Forests are not adequately maintained.

God only knows what the Trump/Musk administration’s concerted effort to drive experienced professionals out of the Pentagon, the intelligence community, the FBI, the EPA, and the Justice Department will do to the performance of those essential organisations. Perhaps within two or four years some of the consequences will become evident to voters. Equally possible, though, is that the declining quality of administration will contribute to heightened attacks on “the administrative state.”

Meanwhile, the disjuncture between our “ideological conservatism” and our “operational liberalism” will produce partisan warfare, huge budget deficits, declining government performance, and even more distrust. Our leaders can either exploit this gap for short-term political gain—as the Trump/Musk administration has done—or try to narrow it by speaking honestly to the American people about their contradictory expectations of government.

Kandinsky’s missing geometric paintings (by Grok)

The Economist on fighting back

A good piece from The Economist. I like its tough minded conclusion “no whingeing”.

One thing they’ve not mentioned but I keep wondering about is treaties of retaliation. The big problem here is that retaliation hurts smaller countries a lot more than it hurts the US. That discloses at least an in-principle case for coordinating retaliation via international treaties. I expect it would be difficult to get much solidarity for such measures, but wouldn’t it be useful to make a few phone calls to Canada to explore the value of a free trade agreement with them. Our economies are so similar it’s hard to see it imposing any difficult economic adjustments on us.

Over time we might expand the SCAT (Sane Countries Agreement on Trade) to other countries. Japan, Mexico, Europe?

For decades America has stood by its friends and deterred its enemies. That steadfastness is being thrown upside down, as Donald Trump strong-arms allies and seeks deals with adversaries. … The 40-odd countries that have put their security in America’s hands since 1945 are suffering a crisis of confidence. …

This loss of faith also reflects a dawning realisation that coercing allies is an inevitable consequence of the MAGA value-free agenda. Allies’ interdependence means that America has more leverage over them than over foes such as Russia or China. For decades Canada, Europe and parts of Asia have trusted America’s “superpower stack”—defence treaties, trade deals, nuclear weapons, the dollar banking system—because it is mutually beneficial. Tragically Mr Trump sees it as a liability. …

On Wall Street there is talk of schemes to depress the dollar. Elon Musk says America should quit NATO …. Europeans are exploring new, once-unthinkable risks: does America have kill switches for F-35 fighter jets? Might it refuse to maintain Britain’s nuclear deterrent?

Asian allies worry that Mr Trump will turn on them next. Australia, Japan, South Korea and others hope his hostility to China runs deep enough that he will not abandon them. But his grievances over trade and defence treaties do not have geographic limits. Given his determination to avoid world war three with Russia over Ukraine, negotiations with China or North Korea could see him offering concessions that weaken allies and make Taiwan more vulnerable.

If you admire America and its transatlantic and Pacific alliances, this shift is so extreme and unfamiliar that it is tempting to deny it is happening and to assume that Mr Trump must backtrack. However, when your people’s safety is at stake, denial is not a plan. America’s allies have a GDP of $37trn, but they lack hard power. Sucking up in the Oval Office and offering to Buy American gets them only so far. Making concessions can encourage more demands, as Panama has found. If allies are unable to defend themselves, some will seek an accommodation with China or Russia.

America’s allies should try to avoid that dismal outcome, starting today. One idea is to deter America from mutual harm. That means identifying unconventional retaliatory measures while calibrating their use to avoid a 1930s-style downward spiral. One option is to slow co-operation on extraterritorial sanctions and export controls. Allies could use their “choke-points” in trade, which we reckon account for 27% of America’s imports, including nuclear fuels, metals and pharmaceuticals. Hidden in the semiconductor-production chain are firms such as Tokyo Electron and ASML in Europe, which are crucial suppliers to America’s tech giants. Smart retaliation against foolish tariffs worked for Europe in the first Trump term. Allies should also identify military pressure-points, such as radars and bases, though they should stop short of exploiting them except in extreme circumstances.

As an insurance policy allies will have to build up their own economic and military infrastructure in parallel to America’s superpower stack. Creating this option will take years. Europe is highly likely to issue more joint debt to finance extra defence spending, and it may keep its own sanctions on Russia even if Mr Trump lifts America’s. All this could split American and European capital markets and ultimately boost the euro’s role as an international currency. In defence, Europe is scrambling to fill gaps in its forces. It is also discussing a continental nuclear deterrent involving France and perhaps Britain. In Asia, South Korea and perhaps Japan may move closer to the nuclear threshold, in order to deter China and North Korea.

The new night watchmen

Last, America’s allies should seek strength in numbers. Europe needs a plan to take over the leadership of NATO, join the CPTPP, an Asian trade deal, and co-operate with Japan and South Korea more closely on military and civilian technology. That would create scale and help manage rivalries. It would also preserve an alternative liberal order, albeit vastly inferior to the original. Allies should be ready to welcome back America under a new president in 2029, though the world will not be the same. Nuclear proliferation may have been unleashed, China will have grown stronger and America’s power and credibility will have been gravely damaged. For its allies, there is no point whingeing: they need to toughen up and get to work.

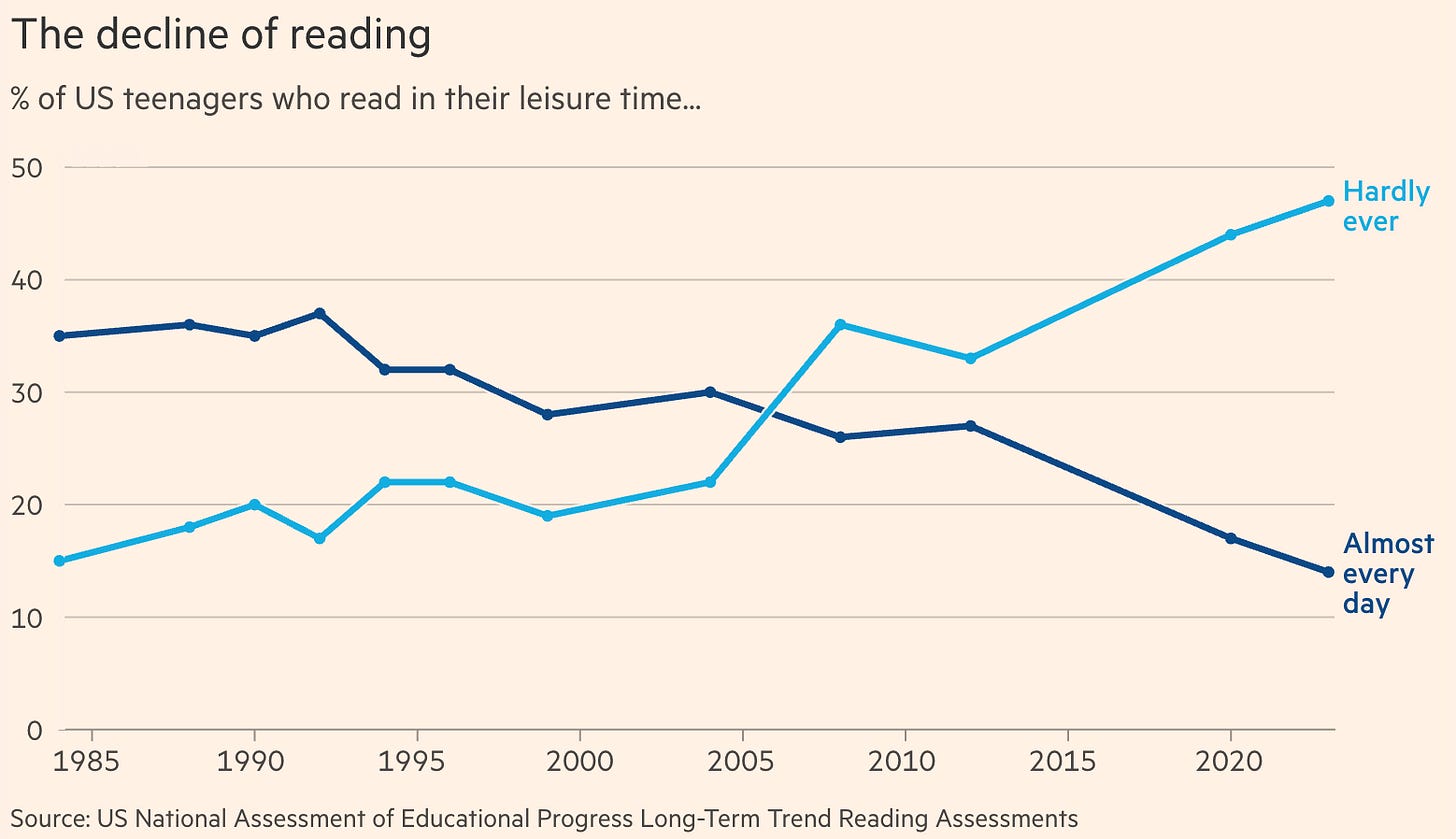

Our declining powers of concentration

You can read all about it in the FT here, but the pictures tell the story. They also tell you, as you read this, that people reading away like you constitute around 14% of the population. Anyway, I’ve got to go and tweet this.

Damned if Britain does, Damned if France doesn’t

Intriguing article about why, being built independently, the French nuclear deterrent remains in tact after the Americans changed sides. And why Britain’s is in disarray because of its entanglement with America’s military technology. So that would make you grateful for the French wouldn’t it? Not so fast.

Beyond the warm words over the past few weeks, London and Paris are largely sticking to the tired national strategies they have clung to for much of the past 50 years: the French talking of European autonomy but in reality pursuing national autonomy; the British pretending they are a mini America but, instead, becoming an ever cheaper imitation. The irony is that, as much as it might pain either side to admit, each would be stronger if it became a little more like the other.

As the former French ambassador to the US, Gerard Araud, has repeatedly pointed out, the Gaullist insistence to retain some national independence from America has proved more farsighted than Britain or Germany would like to admit. While the British military has long prioritised obtaining the latest shiny piece of American military kit available — even at the cost of becoming ever more dependent on the States — the French have prioritised retaining national autonomy, even at the cost of paying more for less.

One such example is the French insistence on a sovereign space policy. They spend around three times more than we do on space programmes, but end up with an inferior product to the one we access courtesy of the Americans, according to those I spoke with. Another example is the French satellite communications operator Eutelsat, which now wants to replace Elon Musk’s Starlink in Ukraine in order to protect European autonomy. But Eutelsat has far fewer satellites operating at far higher altitudes resulting in slower connections. European autonomy, in other words, means paying more for a worse product — at least in the short term.

The upside of this French insistence on national resilience is that in the event of a genuine American withdrawal from Nato — and, perhaps, even an alliance with Russia — the French would at least have the foundations upon which to construct a genuinely independent military. Britain, in contrast, has built its entire strategy around the principle of interoperability with the United States, and so would be sent into a crisis, forcing it to question everything from scratch.

Yet, the corollary of the French insistence on national resilience is that, for all their talk of European autonomy, they cannot bring themselves to do what is necessary to genuinely move in this direction — since it would inevitably undermine their own independence. The most obvious example of this paradox is the fact that in Ukraine’s great battle for survival against Russia — a war Emmanual Macron has held up as an existential test of European security — France has fallen far behind the UK and Germany in supplying the necessary arms for Kyiv to prevail. Why? The answer, it seems, comes in two parts: first, France continues to prioritise national self-reliance over European solidarity; and, second, as one analyst put it to me, France appears “more genuinely broke” even than Britain.

In total, Britain has contributed around €10 billion in military aid to Ukraine, compared with just €3.5 billion from France. As part of this, Britain has been prepared to run down its military stocks. “We’ve given it all away,” said one official I spoke to. By one estimate, Britain has just 14 pieces of heavy artillery left in Estonia, I was told. The French would never entertain this level of exposure. The result, however, is that in the fight for Ukraine’s national survival, Britain has shown more European “solidarity” than France.

Talking European but acting French is the straitjacket Paris seems unable to escape, limiting its ability to lead the Continent into the European revolution it has long championed. Again and again this conundrum plays out. Twenty EU states — including Germany — have called for greater coordination with the UK defence industry to boost the Europe’s resilience, but the French rejected the proposal. Britain has sought a defence pact with the EU in recent months, the process has been held up by the French insistence on negotiating access to Britain’s fishing waters. The inevitable result: French autonomy, European weakness.

Varoufakis on federating Europe as a precondition for fighting Russia

Somewhat misleadingly titled “The Case Against European Rearmament”, I began sceptically and I’m not sure Varoufakis is right. He is, after all repurposing an argument for something he’s argued consistently on other grounds for some time. Yes, but if the Europeans in NATO can’t fund and arrange themselves under unified command how much help would fiscal federalism really be? Anyway, what would I know?

Inducting Ukraine into NATO after forcing Russia back behind its pre-2014 borders has been the only strategic aim EU leaders have allowed themselves to contemplate... Alas, well before US President Donald Trump’s re-election, this aim slipped into the realm of infeasibility.

First, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war economy proved a godsend to his regime. Second, even Trump’s predecessor, Joe Biden, was terminally unwilling to push for Ukraine’s NATO membership... Third, there was strong bipartisan opposition in the United States to the idea of NATO troops fighting alongside Ukrainians.

So, in a display of breathtaking hypocrisy, the many “Putin is the new Hitler” speeches never resulted in a commitment to fight alongside the Ukrainians... Instead, a cowardly West kept sending weapons to the exhausted Ukrainians so that they could defeat the “new Hitler” on its behalf – but on their own.

Inevitably, and despite gallant fighting... European leaders’ sole strategic aim turned to dust – a reality that would have become undeniable regardless of who won the US presidency... Trump merely brought it forward with a brutality reflecting his long-held contempt not just for Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky but also for the EU itself. And so, lacking any Plan B, a Europe weakened by a two-decades-long economic slump is now struggling to respond to Trump’s Ukraine policy.

After the Munich Agreement in 1938, Winston Churchill famously proclaimed... “You chose dishonor, and you will have war.” In their angst not to make the same mistake, EU leaders are about to repeat it, in reverse: their war-until-victory approach will give way to the humiliating peace that Trump will gleefully impose on them...

While it is undoubtedly true that Europe must either rise to the occasion or disintegrate, the question is: Rise how? What’s really wrong with Europe?

It beggars belief that Europeans cannot recognize the answer staring us in the face: Europe is missing a proper Treasury, the equivalent of the State Department, and a Parliament with the power to dismiss what passes as its government (the European Council)... Even worse, there is still no discussion of how to plug these gaping holes in Europe’s institutional architecture.

The EU has always dreaded the beginning of any Ukraine peace process precisely because it would expose the bloc’s nakedness. Who would represent Europe at the negotiating table, even if Trump invited us to join? Even if the European Commission and Council could wave a magic wand to conjure a large, well-armed EU army into existence, who would have the democratic authority to send it into battle?

Moreover, who can raise enough taxes to ensure the EU army’s permanent combat-readiness? The EU’s intergovernmental decision-making means that no one has the democratic legitimacy to make such decisions.

When Ursula von der Leyen... announced her new ReArm Europe initiative, sad memories of the incompetent Juncker Plan, Green Deal, and Recovery Plan came flooding back... Large headline figures were again being tossed about, only to be exposed on closer scrutiny as smoke and mirrors.

Absent the institutions to enact military Keynesianism, the only way Europe can rearm is by shifting funds from its crumbling social and physical infrastructure – further weakening a Europe already reaping the bitter harvest of popular discontent... And for what? Does anyone believe that Putin will be deterred by a Europe that may have a few more shells and howitzers but is drifting further away from the prospect of the federal governance needed to decide matters of war and peace?

ReArm Europe will do nothing to win the war for Ukraine. It will, however, almost certainly drive the EU deeper into its pre-existing economic slump – the underlying cause of Europe’s weakness.

To keep Europeans safe... the EU must embark on its own multipronged Peace Now process. First, the EU must reject outright Trump’s predatory effort to grab Ukraine’s natural resources. Then... the EU should commence negotiations with the Kremlin, offering the prospect of a comprehensive strategic arrangement within which Ukraine becomes what Austria was during the Cold War: sovereign, armed, neutral, and as integrated with Western Europe as its citizens desire.

Third, instead of a permanent stand-off between two large armies along the agreed border, the EU should propose a demilitarized zone... the right of return of all displaced people, a Good Friday-style agreement for the governance of disputed areas, and a Green New Deal for the war-torn areas, jointly financed by the EU and Russia...

Lastly, the EU should use the prospect of relaxing tariffs on Chinese goods... to open negotiations with China with a view to a new security arrangement that reduces tensions and enlists the Chinese to the goal of safeguarding Ukraine’s sovereignty.

If we truly want to strengthen Europe, the first step is not to rearm. It is to forge the democratic union without which stagnation will continue to erode Europe’s capacities, rendering it unable to rebuild what is left of Ukraine once Putin is finished with it.

Great advice on using AI

Australia: land of dreams (good ones — esp for the girls!)

Getting on with the free-fall

I quoted Larry Diamond arguing that the US is in free-fall to authoritarianism. In that context this op ed in a French newspaper draws some telling parallels. [Original in French, Google translation with a couple of minor touch-ups.]

From Democracy to Oligarchy

The parallels between the oligarchic revolution in Athens in -411 and the current coup d’état in the United States are striking.

In the Oligarchic Revolution, the Athenian elite decides to seize power, put an end to democratic institutions, and ally themselves with the enemy city, Sparta, to maintain their hold on Athens. Sound familiar? The historical parallels between the Oligarchic Revolution of 411 BC and the current coup in the United States are striking.

2036 years apart, both the Athenian oligarchy and the American elite present the individual and political freedoms acquired by the people as clear signs of moral and civilizational decline that must be acted upon. In both cases, the oligarchs present themselves as the only ones capable of straightening out the country and purging the nation of its excesses. And, naturally, in both cases, the oligarchy feels authorized to override the laws and subvert the system to the detriment of the people.

War as a context

These “oligarchic revolutions” also fit into a relatively similar historical context: war. The Peloponnesian War was a conflict that broke out between Athens and Sparta. Ideologically, Athens represented “progressive” Greece: its democracy was complete, each citizen enjoyed unprecedented individual freedom as well as the certainty of being able to actively contribute to the politics of his City. Thanks to its democratic practice of drawing lots, it is estimated that an Athenian citizen had a 70% chance of exercising a political role at least once in his life. Conversely, Sparta had kept its original constitution and represented “conservative” Greece. The City was a “gerontocracy” governed by two kings and a council of elders, the Gerousia. The people had practically no chance of ever exercising political responsibility and literally had to choose their representatives using an “applause-meter”.

The two groups of oligarchs also share a similar strategy and modus operandi: they appoint one of their own for new responsibilities created to meet an equally dubious emergency.Thus, in Antiquity, the elite took advantage of the announcement of a military defeat to anticipate supply problems and created a new council: the Probouloï, literally “those who come before the will (of the people)”. This “para-state” group will take up more and more space, to the point of drafting a new oligarchic constitution. This constitution no longer recognizes political rights to more than 5,000 carefully selected citizens and establishes a council of 400 members who hold full powers.

The historical parallel with Elon Musk’s D.O.G.E. is tempting. In any case, its existence is also justified by a narrative of urgency and management of public resources. We cannot yet conclude that D.O.G.E. will go so far as to draft a new American constitution, but it already exercises clear para-state power.

Blatant Treason

The last point of comparison is probably the most disturbing. In order to maintain power, the Athenian elite did not hesitate to call on Sparta, against which the Athenians had been fighting for three [sic] years!

This blatant treason was justified by the desire to ease tensions between the two cities and, in order to facilitate understanding, Athens naturally had to sacrifice its democratic constitution and recognize the new oligarchic order.

The latest developments in the war in Ukraine and the historic U-turn of the Trump administration in favor of Russia take the similarities to an almost unreal degree. All the more so since, in the process, Trump’s emissary does not hesitate to support the most conservative parties in Europe.

The oligarchic coup of the 400 lasted only a year, but democracy was only saved by the revolt of the sailors of Samos. Composed of ordinary citizens, this navy was the greatest force of the City, the purest expression of the term democracy. Namely: demos (the people) and kratos (the force).

We do not yet know how far the D.O.G.E. will go in the United States, but one thing is certain: if the ongoing oligarchic coup is stopped, it will be through the collaboration between the people and their public force to resist the hubris in which their elite has lost itself.

Granta interview with Helen Garner

Helen and her interlocutor have both written books about court cases. But there the resemblance ends. Just look at the picture. Except where otherwise indicated, all the words below are spoken by HG.

My friend was in a traumatised state. But what I really remember was that, towards the end of the trial, the judge came to give his instruction to the jury. And he told the jurors that the evidence against one of the soldiers – a woman – was not sufficient to sustain a conviction, and so they must find her not guilty. The other soldier would carry the can. When he said that, I was thunderstruck, as was everyone in that courtroom. I had this astonishing feeling. It was almost like a vision . . . as if there was some being or consciousness in the room. I felt it’s presence. I sort of gasped. I look back now, and I remember thinking to myself: so it’s true, they really do have to prove it. It was the spirit of the law in the room, I thought. The spirit of the law was restraining our primitive urge for revenge and punishment. I’ve never really gotten over it. …

The idea that you could be arraigned before some powerful force, a social force, that is going to pronounce a judgement on you – there’s something thrillingly intimate about that. Perhaps everyone has, looming inside them a sense that their behaviour will be judged. It suggests an endpoint, when life has few endpoints aside from death.

I’ve discovered as a general principle that people like to be written about. It’s not self-importance, but just having attention paid to what they spend their life doing. I was really moved when I realised that.

A few years after the Farquharson trials, I wrote about the case of Akon Guode, a refugee from South Sudan who drove her children into water. At the sentencing hearing, the only people talking were the judge and barristers, and they were murmuring together, speaking quietly, trying to figure out the right way to deal with this terrible thing, this poor damaged woman. A full-on jury trial, when it’s rolling, is like a symphony performed by an orchestra – all these different witnesses come in and play their solos – and the great roaring pulsing bass that rolls through it all is the law. A sentencing hearing, by comparison, is more like a string quartet. It’s intimate; everyone is quiet. Nobody is grandstanding, nobody is pounding the floor, using rhetorical explosions to make a point. I was really struck by the quiet thoughtfulness. You see that the people who work in the law suffer too. What are you supposed to do to people who have murdered their children? What is the right thing to do? …

In the 1990s, the Judicial College of Victoria ran a writing course for judges, designed to improve their written communication. The college invited local writers to help teach the course, and I agreed to participate. Gosh, I learnt a lot from that. These judges were pressed into doing the course, because their judgments were too long and confusing. On the first day, I was sent various documents to read, and I couldn’t understand a thing*.* I worried I was going to make a fool of myself. Later, when I had a one-to-one workshop with a judge, who was from a mining town in Western Australia, I came clean – I told him I had no idea what his judgment was about. He was genuinely shocked. But when he explained it to me, it was crystalline. He told me there was a bit of land, with some gold in it, and described the mining company dispute. Now I understood perfectly – but none of this was in the judgment. During the workshops, the penny dropped for lots of these judges, and they started to write completely differently. I felt there was a lot of fear in those over-long judgments, and I learned the judges were terrified of being appealed by the court above. Eventually, one year, we got an appeal judge in, who implored them to shorten, to digest, their texts. That was a great illumination for me. It was the first time I understood what you have to do in very complicated stories – you’ve got to stride through it. With the Joe Cinque transcripts, I was creeping along, as if commando-crawling flat on my stomach – and that’s what the judges were doing too. They had to learn to be confident, to give opinions, to take risks, say what they think. Working with judges was the best fun. They were so smart and blocked. Now I’m older than a judge – that’s a strange feeling.

Scott:

[Monkey Grip is] gripping to read, but also almost structureless, a series of episodes. One moment in the book stands out to me now. Nora, the protagonist, is trapped in a relationship. As she escapes her partner, a whirlwind comes after her. She doesn’t understand its meaning, and later, another character explains: ‘It was a doorway specially for you. If you’d known what to do with it, you might have gone into another world.’ The whirlwind makes me think of your earlier description of the spirit of the law, that presence you felt in court. Do you remember the wind, that door?

Garner:

Nobody has ever asked me about that before. I’m really interested that you spotted it. Back then, I was just a slack leftie. I was too much of a smart-arse to open the door, to have a look. As the years have gone by, other things have happened in my life, which have made me much less cynical. In later life, I can’t get through that door quick enough.

Scott:

You described meeting Maria Cinque in the bathroom as a kind of doorway.

Garner:

She opened a door when she said ‘yes’, and I went through it. I tried to back out of the book at other points. I look back on that with such horror. Maria phoned me up, and said to me, ‘What do you mean you won’t write it! We gave you our story! We say write!’ And that was a really good thing she did for me. She opened a door, but she also banged it shut behind me. She drove me on.

Heaviosity half hour

Simone Weil on the abolition of all political parties

Simone Weil the French philosopher, activist, mystic, and all round space-cadet was the first person to win gold at the taking things seriously olympics. Her intellect intimidated Simone de Beauvoir and she refused to live any better than the poor. In consequence she died in 1943 at the age of 34 from tuberculosis complicated by self-imposed starvation.

I was intrigued to find this pamphlet of hers against political parties. She doesn’t say much about what you do without them, or how you stamp them out, but she certainly makes some important points. Her seriousness helps us normies realise how domesticated we have become about party politics — a politics which more or less guarantees the structural separation of what politicians say from what they really believe.

The word ‘party’ is taken here in the meaning it has in Continental Europe. In Anglo-Saxon countries, this same word designates an altogether different reality, which has its roots in English tradition and is therefore not easily transposable elsewhere. The experience of a century and a half shows this clearly enough. [1] In the Anglo-Saxon world, political parties have an element of game, of sport, which is only conceivable in an institution of aristocratic origin, whereas in institutions that were plebeian from the start, everything must always be serious.

At the time of the 1789 Revolution, the very notion of ‘party’ did not enter into French political thinking – except as an evil that ought to be prevented. There was, however, a Club des Jacobins; at first it merely provided an arena for free debate. Its subsequent transformation was by no means inevitable; it was only under the double pressure of war and the guillotine that it eventually turned into a totalitarian party.

Factional infighting during the Terror is best summed up by Tomsky’s memorable saying: ‘One party in power and all the others in jail.’ Thus, in Continental Europe, totalitarianism was the original sin of all political parties.

Political parties were established in European public life partly as an inheritance from the Terror, and partly under the influence of British practice. The mere fact that they exist today is not in itself a sufficient reason for us to preserve them. The only legitimate reason for preserving anything is its goodness. The evils of political parties are all too evident; therefore, the problem that should be examined is this: do they contain enough good to compensate for their evils and make their preservation desirable?

It would be far more relevant, however, to ask: do they do the slightest bit of good? Are they not pure, or nearly pure, evil? If they are evil, it is clear that, in fact and in practice, they can only generate further evil. This is an article of faith: ‘A good tree can never bear bad fruit, nor a rotten tree beautiful fruit.’

First, we must ascertain what is the criterion of goodness.

It can only be truth and justice; and, then, the public interest.

Democracy, majority rule, are not good in themselves. They are merely means towards goodness, and their effectiveness is uncertain. For instance, if, instead of Hitler, it had been the Weimar Republic that decided, through a most rigorous democratic and legal process, to put the Jews in concentration camps, and cruelly torture them to death, such measures would not have been one atom more legitimate than the present Nazi policies (and such a possibility is by no means far-fetched). Only what is just can be legitimate. In no circumstances can crime and mendacity ever be legitimate.

Our republican ideal was entirely developed from a notion originally expressed by Rousseau: the notion of the ‘general will.’ However, the true meaning of this notion was lost almost from the start, because it is complex and demands a high level of attention.

Few books are as beautiful, strong, clear-sighted and articulate as Le Contrat social (with the exception of some of its chapters). It is also said that few books have exerted such an influence – and yet everything has happened, and still happens today, as if no-one ever read it.

Rousseau took as his starting point two premises. First, reason perceives and chooses what is just and innocently useful, whereas every crime is motivated by passion. Second, reason is identical in all men, whereas their passions most often differ. From this it follows that if, on a common issue, everyone thinks alone and then expresses his opinion, and if, afterwards, all these opinions are collected and compared, most probably they will coincide inasmuch as they are just and reasonable, whereas they will differ inasmuch as they are unjust or mistaken.

It is only this type of reasoning that allows one to conclude that a universal consensus may point at the truth.

Truth is one. Justice is one. There is an infinite variety of errors and injustices. Thus all men converge on what is just and true, whereas mendacity and crime make them diverge without end. Since union generates strength, one may hope to find in it a material support whereby truth and justice will prevail over crime and error.

This, in turn, will require an appropriate mechanism. If democracy can provide such a mechanism, it is good. Otherwise, it is not.

In the eyes of Rousseau (and he was right), the unjust will of an entire nation is by no means superior to the unjust will of a single individual.

However, Rousseau also thought that, most of the time, the general will of a whole nation might in fact conform to justice, for the simple reason that individual passions will neutralise one another and act as mutual counterweights. For him, this was the only reason why the popular will should be preferred to the individual will.

Similarly, a certain mass of water, even though it is made of particles in constant movement and endlessly colliding, achieves perfect balance and stillness. It reflects the images of objects with unfailing accuracy; it appears perfectly flat; it reveals the exact density of any immersed object.

If individuals who are pushed to crime and mendacity by their passions can still form, in similar fashion, a people that is truthful and just, then it is appropriate for such a people to be sovereign. A democratic constitution is good if, first of all, it enables the people to achieve this state of equilibrium; only then can the people’s will be executed.

The true spirit of 1789 consists in thinking, not that a thing is just because such is the people’s will, but that, in certain conditions, the will of the people is more likely than any other will to conform to justice.

In order to apply the notion of the general will, several conditions must first be met. Two of these are particularly important.

First, at the time when the people become aware of their own intention and express it, there must not exist any form of collective passion.

It is completely obvious that Rousseau’s reasoning ceases to apply once collective passion comes into play. Rousseau himself knew this well. Collective passion is an infinitely more powerful compulsion to crime and mendacity than any individual passion. In this case, evil impulses, far from cancelling one another out, multiply their force a thousandfold. Their pressure becomes overwhelming – no-one could withstand it, except perhaps a true saint.

When water is set in motion by a violent, impetuous current, it ceases to reflect images. Its surface is no longer level; it can no more measure densities. Whether it is moved by a single current or by several conflicting ones, the disturbance is the same.

When a country is in the grip of a collective passion, it becomes unanimous in crime. If it becomes prey to two, or four, or five, or ten collective passions, it is divided among several criminal gangs. Divergent passions do not neutralise one another, as would be the case with a cluster of individual passions. There are too few of them, and each is too strong for any neutralisation to take place. Competition exasperates them; they clash with infernal noise, and amid such din the fragile voices of justice and truth are drowned.

When a country is moved by a collective passion, the likelihood is that any individual will be closer to justice and reason than is the general will – or rather, the caricature of the general will.

The second condition is that the people should express their will regarding the problems of public life – and not merely choose among various individuals; or, worse, among various irresponsible organisations (for the general will does not have the slightest connection with such choices).

If, in 1789, there was to a certain degree a genuine expression of the general will – even though a system of people’s representation had been adopted, for want of ability to invent any alternative – it was only because they had something far more important than elections. All the living energies of the country – and the country was then overflowing with life – sought expression through means of the cahiers de revendications (statements of grievances). Most of those who were to become the people’s representatives first became known through their participation in this process, and they retained the warmth of the experience. They could feel that the people were listening to their words, watching to see if their aspirations would be correctly interpreted. For a while – all too briefly – these representatives truly were simple channels for the expression of public opinion.

Such a thing was never to happen again.

Merely to state the two conditions required for the expression of the general will shows that we have never known anything that resembles, however faintly, a democracy. We pretend that our present system is democratic, yet the people never have the chance nor the means to express their views on any problem of public life. Any issue that does not pertain to particular interests is abandoned to collective passions, which are systematically and officially inflamed.

The very way in which words such as ‘democracy’ and ‘republic’ are being used obliges us to examine with extreme attention two problems:

1. How to give the men who form the French nation the opportunity to express from time to time their judgment on the main problems of public life?

2. How, when questions are being put to the people, can one prevent their being infected by collective

passions?

If one neglects to consider these two points, it is useless to speak of republican legitimacy.

Solutions will not easily be found. Yet, after careful examination, it appears obvious that any solution will necessarily involve, as the very first step, the abolition of all political parties.

*

To assess political parties according to the criteria of truth, justice and the public interest, let us first identify their essential characteristics.

There are three of these:

1. A political party is a machine to generate collective passions.

2. A political party is an organisation designed to exert collective pressure upon the minds of all its individual members.

3. The first objective and also the ultimate goal of any political party is its own growth, without limit.

Because of these three characteristics, every party is totalitarian – potentially, and by aspiration. If one party is not actually totalitarian, it is simply because those parties that surround it are no less so. These three characteristics are factual truths – evident to anyone who has ever had anything to do with the every-day activities of political parties.

As to the third: it is a particular instance of the phenomenon which always occurs whenever thinking individuals are dominated by a collective structure – a reversal of the relation between ends and means.

Everywhere, without exception, all the things that are generally considered ends are in fact, by nature, by essence, and in a most obvious way, mere means. One could cite countless examples of this from every area of life: money, power, the state, national pride, economic production, universities, etc., etc.

Goodness alone is an end. Whatever belongs to the domain of facts pertains to the category of means. Collective thinking, however, cannot rise above the factual realm. It is an animal form of thinking. Its dim perception of goodness merely enables it to mistake this or that means for an absolute good.

The same applies to political parties. In principle, a party is an instrument to serve a certain conception of the public interest. This is true even for parties which represent the interests of one particular social group, for there is always a certain conception of the public interest according to which the public interest and these particular interests should coincide. Yet this conception is extremely vague. This is true without exception and quite uniformly. Parties that are loosely structured and parties that are strictly organised are equally vague as regards doctrine. No man, even if he had conducted advanced research in political studies, would ever be able to provide a clear and precise description of the doctrine of any party, including (should he himself belong to one) of his own.

People are generally reluctant to acknowledge such a thing. If they were to confess it, they would naively be inclined to attribute their incapacity to their own intellectual limitations, whereas, in fact, the very phrase ‘a political party’s doctrine’ cannot have any meaning.

An individual, even if he spends his entire life writing and pondering problems of ideas, only rarely elaborates a doctrine. A group of people can never do so. A doctrine cannot be a collective product.

One can speak, it is true, of Christian doctrine, Hindu doctrine, Pythagorean doctrine, etc. – but then what is meant by this word is neither individual nor collective; it refers to something that is infinitely higher than these two realms. It is purely and simply the truth.

The goal of a political party is something vague and unreal. If it were real, it would demand a great effort of attention, for the mind does not easily encompass the concept of the public interest. Conversely, the existence of the party is something concrete and obvious; it is perceived without any effort. Therefore, unavoidably, the party becomes in fact its own end.

This then amounts to idolatry, for God alone is legitimately his own end.

The transition is easily achieved. First, an axiom is set: for the party to serve effectively the concept of the public interest that justifies its existence, there is one necessary and sufficient condition: it should secure a vast amount of power.

Yet, once obtained, no finite amount of power will ever be deemed sufficient. The absence of thought creates for the party a permanent state of impotence, which, in turn, is attributed to the insufficient amount of power already obtained. Should the party ever become the absolute ruler of its own country, inter-national contingencies will soon impose new limitations.

Therefore the essential tendency of all political parties is towards totalitarianism, first on the national scale and then on the global scale. And it is precisely because the notion of the public interest which each party invokes is itself a fiction, an empty shell devoid of all reality, that the quest for total power becomes an absolute need. Every reality necessarily implies a limit – but what is utterly devoid of existence cannot possibly encounter any form of limitation. It is for this reason that there is a natural affinity between totalitarianism and mendacity.

Many people, it is true, never contemplate the possibility of total power; the very thought of it scares them. The notion is vertiginous and it takes a sort of greatness to face it. When these people become involved with a political party, they merely wish it to grow – but to grow as a thing that knows no limit. If this year there are three more members than last year, or if the party has collected one hundred francs more, they are pleased. They wish things might endlessly continue in the same direction. In no circumstance could they ever believe that their party might have too many members, too many votes, too much money.

The revolutionary temperament tends to envision a totality. The petit-bourgeois temperament prefers the cosy picture of a slow, uninterrupted and endless progress. In both cases, the material growth of the party becomes the sole criterion by which to measure the good and the bad of all things. It is exactly as if the party were a head of cattle to be fattened, and as if the universe was created for its fattening.

One cannot serve both God and Mammon. If one’s criterion of goodness is not goodness itself, one loses the very notion of what is good.

Once the growth of the party becomes a criterion of goodness, it follows inevitably that the party will exert a collective pressure upon people’s minds. This pressure is very real; it is openly displayed; it is professed and proclaimed. It should horrify us, but we are already too much accustomed to it.

Political parties are organisations that are publicly and officially designed for the purpose of killing in all souls the sense of truth and of justice. Collective pressure is exerted upon a wide public by the means of propaganda. The avowed purpose of propaganda is not to impart light, but to persuade. Hitler saw very clearly that the aim of propaganda must always be to enslave minds. All political parties make propaganda. A party that would not do so would disappear, since all its competitors practise it. All parties confess that they make propaganda. However mendacious they may be, none is bold enough to pretend that in doing so, it is merely educating the public and informing people’s judgment.

Political parties do profess, it is true, to educate those who come to them: supporters, young people, new members. But this is a lie: it is not an education, it is a conditioning, a preparation for the far more rigorous ideological control imposed by the party upon its members.

Just imagine: if a member of the party (elected member of parliament, candidate or simple activist) were to make a public commitment, ‘Whenever I shall have to examine any political or social issue, I swear I will absolutely forget that I am the member of a certain political group; my sole concern will be to ascertain what should be done in order to best serve the public interest and justice.’

Such words would not be welcome. His comrades and even many other people would accuse him of betrayal. Even the least hostile would say, ‘Why then did he join a political party?’ – thus naively confessing that, when joining a political party, one gives up the idea of serving nothing but the public interest and justice. This man would be expelled from his party, or at least denied pre-selection; he would certainly never be elected.

Furthermore, it seems inconceivable that anyone would dare to utter such words. In fact, if I am not mistaken, such a thing has never happened. If such language has ever been used, it was only by politicians who needed to govern with the support of other parties. And even then, the words had a somewhat dishonourable ring to them. Conversely, everybody feels that it is completely natural, sensible and honourable for someone to say, ‘As a conservative . . .’ or ‘As a Socialist, I do think that . . .’

Actually, this sort of speech is not limited to partisan politics; people are not ashamed to say, ‘As a Frenchman, I think that . . .’ or ‘As a Catholic, I think that . . .’

Some little girls, who declared they were committed to Gaullism as the French equivalent of Hitlerism, added: ‘Truth is relative, even in geometry.’ Indeed, this is the heart of the matter.

If there were no truth, it would be right to think in such or such a way, when one happens to be in such or such a position. Just as one’s hair is black, brown, red or blond because one happened to be born that way, one may also express such or such a thought. Thought, like hair, is then the product of a physical process of elimination.

If, however, one acknowledges that there is one truth, one cannot think anything but the truth. One thinks what one thinks, not because one happens to be French or Catholic or Socialist, but simply because the irresistible light of evidence forces one to think this and not that.

If there is no evidence, if there is doubt, then it is evident that, given the available knowledge, the matter is uncertain. If there is a small probability on one side, it is evident that there is a small probability – and so on. In any case, inner light always affords whoever seeks it an evident answer. The content of the answer may be more or less affirmative – never mind. It is always susceptible to revision, yet no correction can be effected unless it is through an increase of inner light.

If a man, member of a party, is absolutely determined to follow, in all his thinking, nothing but the inner light, to the exclusion of everything else, he cannot make known to the party such a resolution. To that extent, he is deceiving the party. He thus finds himself in a state of mendacity; the only reason why he tolerates such a situation is that he needs to join a party in order to play an effective part in public affairs. But then this need is evil, and one must put an end to it by abolishing political parties.

A man who has not taken the decision to remain exclusively faithful to the inner light establishes mendacity at the very centre of his soul. For this, his punishment is inner darkness.

It would be useless to attempt an escape by establishing a distinction between inner freedom and external discipline, for this would entail lying to the public, towards whom every candidate, every elected representative, has a special duty of truthfulness. If I am going to say, in the name of my party, things which I know are the opposite of truth and justice, should I first issue a warning to that effect? If I don’t, I lie.

Of these three sorts of lies – lying to the party, lying to the public, lying to oneself – the first is by far the least evil. Yet if belonging to a party compels one to lie all the time, in every instance, then the very existence of political parties is absolutely and unconditionally an evil.

In advertisements for public meetings, one frequently reads things like this: ‘Mr X will present the Communist point of view (on the issue which the meeting shall address). Mr Y will present the Socialist point of view. Mr Z will present the Liberal point of view.’

How do these wretches manage to know the various points of view they are supposed to present? Who can have instructed them? Which oracle? A collectivity has no tongue and no pen. All the organs of expression are individual. The Socialist collectivity is not embodied in any person, and neither is the Liberal one. Stalin embodies the Communist collectivity, but he lives far away and it is not possible to reach him by telephone before the meeting.

No, Mr X, Mr Y, Mr Z each consulted themselves. Yet, if they were honest, they would first have put themselves in a special psychological state – a state similar to the one which is usually attained in the atmosphere of Communist, Socialist or Liberal gatherings.

If, having put oneself in such a state, one were to abandon oneself to automatic reactions, one would quite naturally speak a language in full conformity with the Communist, Socialist or Liberal ‘point of view.’ To achieve this result, there is but one condition: one must absolutely resist the contemplation of truth and justice. If such contemplation were to take place, one would run a horrible risk: one might express a ‘personal point of view.’

When Pontius Pilate asked Jesus, ‘What is the truth?,’ Jesus did not reply. He had already answered when he said, ‘I came to bear witness to the truth.’