Elephant in the room edition

And other highlights of terifficness and semi-terrificness I found this week

We raised $5,500 for very poor people.

I’m really excited to say that before the end of the financial year readers donated $1,375. Thanks to Bridget, Evan, Thilak, Peter and to Tanya who made a large donation. I matched it and our joint contribution was matched again. So $5,500 got raised for people who could really do with a break. Thank you all and let’s raise more next year.

Neoliberalism: what is it good for?

This discussion emerged from an email from my colleague Gene Tunny wondering whatever happened to Australian exceptionalism — that period during which he cut his teeth in the Treasury when Australian policy makers worked tirelessly to reshape the Australian economy to make it more productive and government politicians regarded this as one of their core tasks.

We talked about how past leaders made big changes, like reducing tariffs and improving education. I painted a picture from my own — unusual — point of view which is that my father was an important figure in helping 'sell' economic reform to governments in the 1960s and then became part of early neoliberalism as an academic advisor to the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet beginning shortly after the election of the Whitlam Government to around mid-1976.*

I argue that early neoliberalism was highly successful. It picked plenty of low hanging fruit and saw itself as problem solving. As it became a dominant way of thinking, it became formularised — and understood as a summary aesthetic that 'market based' solutions were better. This idea was way too vague and vibey to be of practical use, but it operated to systematically bias the way people thought about things and set them up to make mistakes that were so large that there’s a fair case to be made that late reform did more harm than good. As I wrote in this op ed in 2014:

Australia was a standard-bearer in areas like trade and agricultural protection, the two airline policy and shopping hours. There, with the stroke of a pen, we swept away the detritus of a century’s ad hoc political favouritism. And unlike our peers in the Anglosphere, we also expanded funding for the safety net – bolstering equity.

But beyond that, as we’ve learned (or have we?), considering policy alternatives against a criterion as crude as how ‘free market’ they are doesn’t work so well. In infrastructure, utility and financial reform, where monopoly and asymmetric information problems abound, regulation remains inevitable and new rent seeking political pathologies lie in wait for those unpicking the old ones. Here our reform efforts brought forth excessively priced mortgages, toll-ways, desalination plants and airports with the political and official insiders championing the changes parachuting into lucrative careers with the corporate beneficiaries of their reforms to lobby their successors. We’ve seen massive over-investment in electricity transmission and under-investment in other infrastructure.

Gene and I discuss a range of policy questions, but Gene is interested in my experience in reforming car manufacturing in Australia and we spend a fair bit of time on that. We also discuss the Higher Education Charge (HECs) and the outsourcing of the Commonwealth Employment Services to illustrate some of the good and the bad of the new approach. And we also talk about the disasters like public-private partnerships for infrastructure, particularly toll roads. We also swapped some ideas about how New Zealand has done so much worse than Australia since the '70s. I don't know about Gene, but my speculations on that subject should be taken as just that — speculations and pretty uninformed.

* In case you're interested, the new PM, Malcolm Fraser did not get rid of him. Instead Dad had always felt bad about giving the ANU only half of his time so he withdrew from the arrangement with PM&C when there seemed to be less interest in his services.

Neoliberalism — another example

John Quiggin and the Overton Gradient

(Not to mention Overton’s Elephant and Overton's Mouse)

With inflation stuck at 4%, what a terrible problem that it will probably take a deliberately engineered recession to get it back into target. If only the optimal rate of inflation were 4%. Oh wait … No-one can be sure what the optimal rate is, but from the flimsy knowledge we have, 4% is a better guess than 2-3%. Yet to even say so is to play the role of the ‘wet’, the soft-headed person who won’t make hard choices. Welcome to Overton’s gradient.

Named after the American free-market policy analyst Joseph Overton, the Overton Window defines what policy options can be seriously considered and what is regarded (without further thought) as beyond the pale. Thus when Cambridge Economics Professor Cecil Pigou suggested confiscating a portion of the wealth of the richest Britons to pay for WWI, the suggestion was not within the Overton Window, not worthy of serious consideration.

The Overton Window is policed by a committee known as the VSOWP — which, as we all learn in Public Policy 101 stands for Very Serious Overton Window People. The VSOWP are convinced for instance that we couldn’t have inheritance taxes in Australia. So no mainstream politician goes so far as to mention them. Why not? Well because, and did I mention that no politician mentions them? Anyway, look over there.

Of course other things being equal the VSOWP are correct. If you just get up in Parliament and say ‘what this place needs is death duties’ you will not be treated as a political mastermind. But the same can be said of raising any tax. But introduced as the least painful of available options next time there’s a crisis and a fiscal crunch — it could easily squeeze its way into the Overton Window. Except that it won’t because … well you have to put your application into the VSOWP.

In any event, I’ve previously expanded the use of the adjective Overton to allow for the Overton Juggernaut — that’s what every Very Serious Person knows, just knows whether it’s right or not. You know, like it certainly wouldn’t be good to change course and move interest rates sharply lower when forecasters are predicting rising unemployment. And this is itself an example of the Overton Gradient. The Overton Gradient tells you, that when you have a choice, there’s a soft option and a hard one. And soft-options are for weakly, ill-formed folk with no moral or even intellectual fibre.

And the nature of the Overton Gradient explains the more specific phenomena of Overton’s Elephant and Overton’s Mouse. The elephant is the fact that 4% is a good guess at the optimal inflation rate. So it looks like the best inflation target. And the mouse is all the other things the Reserve and the other Serious Folks are talking about instead — more productivity, investment, innovation and wellbeing. No problem with any of those, but they should be addressed on their merits. They’re not substitutes for better macro-economic policy.

Over to John Quiggin.

The release of recent data suggesting that inflation appears to be stuck at 4%, above the Reserve Bank of Australia’s target range of 2% to 3%, has raised plenty of concern among economic and political commentators. These commentators might be surprised to learn that many, perhaps most, macroeconomists who have looked at the question have concluded that a 4% inflation rate would be the ideal target, at least providing that wages and other incomes kept pace.

The underlying reasoning is simple. Interest rates are the main tool of monetary policy. In a deep recession such as that following the global financial crisis, or in an emergency such as that created by the Covid-19 pandemic, it is desirable that the interest rate should be well below the rate of inflation. That is, the real interest rate, adjusted for inflation, should be negative.

But if the rate of inflation is too low, this policy is limited by the fact that interest rates can’t go [much] below zero. … If a low inflation target is such a dubious idea, why was it adopted in the first place? The answer, surprisingly enough, comes from New Zealand. The first central bank to adopt an inflation target was the Reserve Bank of New Zealand in 1989. The policy was introduced by the then Reserve Bank governor, Don Brash, later to reinvent himself as a rightwing (and then far-right) politician. Brash was backed by then finance minister, Roger Douglas, whose political career followed a similar trajectory.

A range of 0% to 2% was picked, without any theoretical basis, as the lowest that could plausibly be pursued. As Douglas said later, “I just announced it was gonna be 2%, and it sort of stuck.” While the NZ central bank was the first to adopt a 2% inflation target, others were quick to follow. …

At the time, New Zealand was seen as being a star performer in economic reform, likely to overtake Australia …. In reality, though, New Zealand’s economic performance has been miserable. …

While many explanations have been offered for New Zealand’s relative decline, the simplest is that of repeated failures in macroeconomic management. New Zealand has experienced a string of recessions since the adoption of inflation targeting, mostly reflecting excessively rigid application of tight monetary policy. Contrary to the idea of a recession as a temporary disruption, these recessions (particularly that of the early 1990s and the global financial crisis) seem to have shifted the country onto a permanently lower growth path.

Elsewhere, inflation targeting worked reasonably well until the GFC. But in the long period of depressed activity that followed, central bank interest rates were stuck at or near zero. Despite this failure, central banks retained the power and prestige they had attained in the early days of inflation targeting. Unsurprisingly, they have been highly resistant to any change to inflation targets, even though they have no convincing defence of the status quo. Instead, they rely on the fact that any change would be bad for faith in the central banks.

The recent review of the RBA spells this out. After conceding the strength of arguments for a higher inflation target, the review panel concluded: “Regardless of the merits of higher inflation in general, the Review does not recommend increasing the inflation target during the present period of high inflation. To do so could undermine the credibility of the RBA in responding to future periods of above-target inflation.”

Of course, once we have ground our way back down to the target, the idea of raising it will be dismissed; it would be throwing away costly gains. So, if you are struggling with higher interest rates or worried about higher unemployment, remember that this is the price we have to pay to restore the “credibility” of the Reserve Bank.

Rishi Sunak: Nice guy

How to lose an election

Just as free speech is not to allow people to say things we’re OK with, but rather things that offend us, so the test of a democracy is how the losers lose. In that regard the UK’s democracy remains strong — at least at the level of official statements. (HT: Video from Stephen Mayne’s Twitter feed). In the longer term of course it has been profoundly weakened by numerous things we don’t understand well and almost certainly by news as propaganda.

Recycling plastics (into pollutants)

This is an unusual article for Quillette. It is contrarian and hostile to the very worst of environmentalism — which is no surprise for Quillette, but it also shares with much environmental tokenism the idea that we will be in crisis if we don’t find an alternative to landfill.

Gentle reader, reducing landfill is not an environmental objective unless we cannot find a way of preventing landfill from damaging the environment. And unless it’s toxic — and most plastic is not (and even then its toxicity can be managed with appropriate lining of the landfill) — burying plastic in the ground is a perfectly fine thing to do — unless it’s more cost effective to do something else.

And given that it’s way more costly than burying plastic waste, most plastic recycling is a monumental waste of your money and the community’s resources. Be that as it may, the real significance of the story is that plastic recycling seems to be anti-environmental policy — substantially increasing the emissions of microplastics into the environment. Naturally the Greens and environmentalists everywhere are calling for an immediate pause on plastic recycling until we can be more confident that spending all that money on it is safe.

Only kidding.

The article itself is paywalled after three paragraphs, but you can listen to the whole thing being read. I got bored after it had made and apparently proved its point, but it’s worth taking note of.

By now, you probably know that plastic recycling is a scam. If not, this white paper lays out the case in devastating detail. To summarise, amid calls to reduce plastic garbage in the 1970s and ’80s, the petrochemical industry put forth recycling as a red herring to create the appearance of a solution while it continued to make as much plastic as it pleased. Multiple paper trails indicate that industry leaders knew from the start that recycling could never work at scale. And indeed, it hasn’t. Only about nine percent of plastic worldwide gets recycled, and the US manages only about six percent.

As bad as this is, the situation might actually be much worse. According to an emerging field of study, the facilities that recycle plastic have been spewing massive amounts of toxins called microplastics into local waterways, soil, and air for decades. In other words, the very industry created to solve the plastic-waste problem has only succeeded in making it worse, possibly exponentially so. While the study that kicked off this new field received some press coverage when it appeared last year, the far-ranging import of its findings has yet to be fully integrated into environmental science. If the research is even close to accurate, and to date it has not been substantively challenged, the implications for waste management policies across the globe will be game-changing.

For a start, no one has fully documented the massive amounts of microplastics (MPs) at issue here. As I’ll demonstrate below, not only do plastic recyclers appear to be a major source of MP contamination, they may very well be the number one source of primary microplastic pollution on the entire planet. So, from an environmental perspective, recycling plastic could be doing far more harm than good. Even some environmentalists are coming around to this view.

Chris Wallace on dissent, solidarity and silence

Chris Wallace explores some of the deeper issues in the latest procedural drama within the ALP. In effect caucus solidarity has become an instrument not of coraling dissent within party walls, but of silencing dissent altogether. Wallace says the change occurred on Rudd’s watch, which seems right, but it seems to me that much deeper forces are at work as careerism increasingly pervades our public life for reasons that aren't all that clear. But the bottom line is that sound chaps don’t get in the way of powerful chaps. And that rule seems to be increasingly the norm, not just in politics and bureaucracy, but more widely.

Critics shouldn’t be so fast to dismiss [The Australian Labor Party’s solidarity pledge] as antiquated simply because it’s part of Labor’s century-plus origin story. Today it’s current under a different name in Silicon Valley, for example, because of its intrinsic utility. There it’s called “disagree and commit”. …

“Disagree and commit” evolved to become common in today’s entrepreneurial startups as a way of enabling talented, headstrong individuals to have their say, make a decision, and then get together behind it – some more cheerfully than others.

The “disagree and commit” cycle is repeated over and over again in startups as they craft their path forward. It means some participants will exit, sometimes painfully, at different points along the way.

It’s pervasive because it makes so much more sense than the alternative of startups being at perpetual risk of flying apart under the centrifugal force generated by those who can’t “disagree and commit”. It’s a regular part of entrepreneurial life, just as it’s a regular part of political life for Labor MPs. …

Caucus used to be a place where vigorous disagreement could occur in a group setting, with MPs joining in spirited debate on contentious issues. People felt seen and heard by colleagues and the party leadership, because they literally were.

The group context made all the difference. MPs shy of speaking up gained confidence when others did so, and spoke up too. Multiple MPs voicing passionate concerns in front of the whole caucus forced the leadership to take notice even – and especially – if it didn’t want to.

Policy could actually change as a result of caucus debate. Labor prime minister Bob Hawke, for example, had to reverse his support for US testing of MX missiles in the Pacific as a result of caucus activism. Hawke disagreed with, but ultimately had to commit to, the overwhelming caucus view opposing it.

Though there has been no rule change stopping this, caucus doesn’t operate that way anymore.

An unhealthy habit of silence developed in cabinet as well as caucus under the prime ministership of Kevin Rudd (2007–10 and 2013), who was known for enraged personal pursuit of those with alternative views. Under Rudd it was all “commit” and no “disagree”.

Labor frontbenchers and backbenchers developed ways of working together behind the scenes around that, out of reach of Rudd’s fury, to try to get things done.

The habit that developed then largely continues, with deleterious effect, including under current Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. …

How much better it would be to have Labor ministers speak up again in cabinet, and Labor MPs speak up again in caucus, enabling laggard policies to be fixed faster and passionate MPs to make proper contributions in a full-blooded “disagree and commit” environment.

This would take courage by cabinet ministers and caucus members alike. It would model for new MPs like Payman the way to get policy changed for the better inside Labor governments.

Their right to other’s silence

From this tweet.

The Soul of Civility

I didn’t find the title of this piece particularly promising. While the collapse in civility is hugely consequential, a lot of chat about it doesn’t rise much above the thought that it would be better if we were all a bit nicer to each other — an idea I already had covered back in my cartooning days.

Anyway, what I feared would be a bland, self-helpy effort, does seem to me to have something more that that to say.

Alexandra Hudson: … While I was working in government in DC in this very divided moment, I saw two extremes. On one hand, there were the people with sharp elbows, the ones who were hostile and willing to step on anyone to get ahead. And on the other hand, there were these people who were incredibly polished and suave and poised, and I thought that these were my people. I realized, though, that these polished people, these were the ones who would smile and flatter me and others and then stab us in the back the moment that we no longer served their purposes.

At first, I thought that these two groups of people were polar opposites. And then I realized, instead, that they represented two sides of the same coin. They both instrumentalize others as opposed to seeing human beings as worthy of respect just by virtue of being human.…

That helped me realize this essential distinction between civility and politeness. Politeness is manners, it’s technique, it’s etiquette, it’s behavior, it’s at the superficial, external level alone. But civility is a disposition of the heart. It’s a way of seeing others as our moral equals and treating them with … respect …. In light of that—and this is key—sometimes actually respecting someone requires being impolite. It means telling a hard truth, engaging in robust debate, telling someone that you disagree, that you think that they’re wrong. That’s actually a form of respecting someone …

AD: You say in the book that politeness has become a tool of silence and suppression, but civility demands speaking truth to power. Can you unpack that?

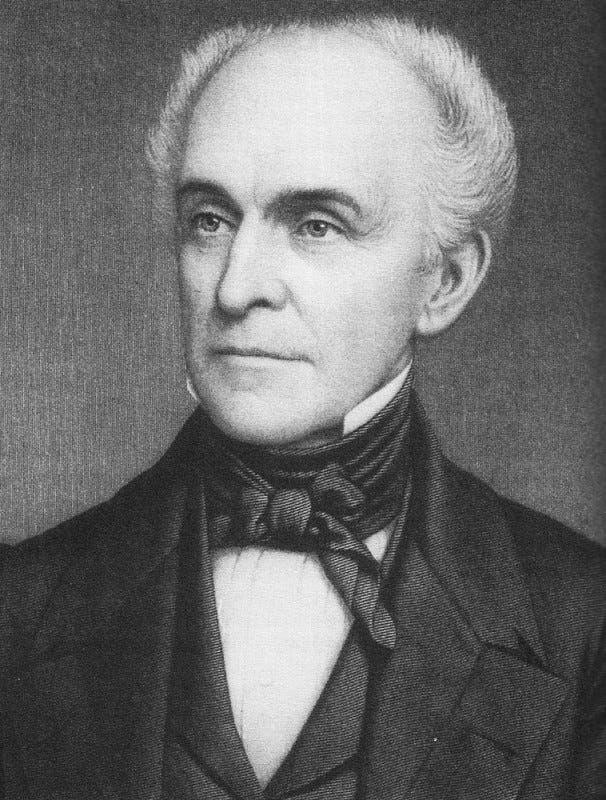

AH: To illustrate that point, I tell the story in my book of Edward Coles. … When he was in James Madison’s White House … he decided to confront America’s primary founding father, the architect of liberty, Thomas Jefferson, with America’s—and Jefferson’s—foundational hypocrisy. Coles wrote Jefferson a letter asking him how he could own slaves while also holding this sentiment that all men are created equal.

So he wrote this letter to Jefferson saying, “Look, I’m part of this abolitionist movement and we could really use your support. Will you please live up to your own ideals and be part of this movement with us?” Thomas Jefferson wrote back saying, “Edward, great to hear from you. Thanks for your note. Thanks for the update. I hear what you’re saying. You’re right. Abolition is going to happen. It’s clear that history is moving in this direction, but you don’t need my help. I’m too old. This is a fight for younger men.” And he just went through this litany of excuses for why he was unwilling to take up the abolitionist cause.

But Coles didn’t leave it there. He wrote back again and said, “I hear what you’re saying. It’s not an excuse. Look at Benjamin Franklin. He was no spring chicken, and he supported this movement.” He didn’t let Jefferson off the hook. Jefferson never wrote back after that.

It’s not polite to call someone out for not living up to their ideals. But it’s really easy to see how, in fact, Edward Coles perhaps respected Jefferson enough to do that, not to coddle Jefferson. He esteemed him, he revered him. He admired everything that he had done and achieved in his life. And he said, “But that’s still not good enough. You’re not living up to those ideals. There’s this misalignment in your value system and your ideas and your practice.” So I love that Coles’s story illustrates the distinction between civility and politeness, why civility demands respecting ideas and people enough to speak truth to power.

In response to this article I looked up the correspondence between Coles and Jefferson and its aftermath — it is at the end of this newsletter.

Felix Martin on why AI may impair productivity!

The world’s advanced economies are in the grip of a prolonged productivity crisis. …Artificial intelligence is hailed as a potential game-changer. BlackRock CEO Larry Fink claims it will “transform margins across sectors”. … The McKinsey Global Institute says it could add up to $26 trillion to global GDP.

Investors should beware of the hype. Four features of AI suggest that while its impact on the bottom line of some companies may be positive, its economy-wide consequences will be less impressive. Indeed, self-teaching computers may make the productivity crisis worse. …

AI models are digital Babylonians, rather than automated Einsteins. They have revolutionised the ability of computers to identify useful patterns in huge datasets, but they are incapable of developing the causal theories needed for new scientific discoveries. …Without causal reasoning, AI’s predictive genius will not be making human scientists redundant.

A second argument made for AI is that it will reduce corporate costs by automating much more basic knowledge work. … One recent study found that introducing AI-powered chatbots helped customer support functions resolve 14% more issues per hour. The caveat is that the likely aggregate impact of such efficiency improvements is surprisingly modest.

Daron Acemoglu of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology estimates that 20% of current labour tasks in the United States could be performed by AI, and that in around a quarter of those cases it would be profitable to replace humans with an algorithm. Yet even if this replaces nearly 5% of all work, Acemoglu calculates that broad productivity growth would increase by only around half a percentage point over ten years. That is barely a third of the ground lost since 2008. …

The third challenge … is that in an important class of cases, embracing AI may send productivity gains into reverse. … The history of quantitative investing provides a cautionary tale. In the early 1970s, investors first identified systematic factors such as value and momentum, and the few firms willing to spend money on statistical research enjoyed super-normal returns. By the end of the decade, however, their competitors were running the numbers too. The excess returns were competed away, but everyone continued to incur the costs. …

That implies a fourth feature of AI which will deliver a more insidious blow to productivity. If an AI arms race makes massive capital investment the table stakes just to maintain market share, smaller players will inevitably be squeezed out. Industries will tend towards oligopoly. Competition will tend to decrease. Innovation will suffer – and productivity will slump even more.

In 1987, the Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow bemoaned the fact that “you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics." The effects of AI may soon be all too evident – just unfortunately in the wrong direction.

Sam Roggeveen on building an alliance with Indonesia

Makes sense to me.

Indonesia is not just any Southeast Asian nation. With 280 million people Indonesia is 60 per cent larger in population than the next largest Southeast Asian country, the Philippines, and the fourth largest in the world. … [It’s] GDP is almost three times larger than that of the region’s next biggest economy, Thailand. And … it might be the fourth-biggest economy in the world by 2050. …

Then there’s geography. Indonesia is not just the largest country in Southeast Asia by population, economy and territory, it is also the closest to Australia. In my book The Echidna Strategy, I argued that Australia’s biggest strategic asset is distance. But that judgment applies mainly to the threat from China’s military. The value of distance is routinely underestimated in Australia, yet it offers a huge degree of protection because it is so difficult and expensive for China to project military force over vast distances.

These constraints don’t apply to Indonesia which, if it had the military resources, could use its own vast territory to threaten Australia. Indonesia’s military remains weak … but the precondition for military strength is wealth, and given that Indonesia is climbing fast as an economic power, we should assume its military strength will grow too.

That means Australia’s luck will increasingly depend on Indonesian good will. Whether Indonesia is ever a threat to Australia will depend far less on whether it can do us harm, and much more on whether it wants to do us harm.

The downside risks are huge. A wealthy Indonesia which is hostile to Australia would present a much more serious threat to our security than China does. But the opportunity is equal in scale. A wealthy Indonesia engaged in a close military partnership with Australia would be a major security asset for Canberra. Which is why I have written a feature essay for the latest issue of Australian Foreign Affairs calling for Australia to forge a military alliance with Indonesia.

[A] new agreement would fulfill the single key requirement for an effective military pact: that it must be based on a commonly perceived threat which the parties to that alliance have a vital interest in meeting.

That threat, of course, is China. But it’s important to be specific about this. The alliance I call for in my article is designed not to exclude China from our region or threaten its vital interests, but solely to prevent Chinese dominance of maritime Southeast Asia. It is impossible for Australia and Indonesia, even with their resources combined, to stop China being the leading power in this part of the world. Nobody, not even the United States, will be able to keep up with the modernisation and expansion of China’s maritime forces.

But thankfully, the job of frustrating any Chinese attempt to dominate maritime Southeast Asia is made easier by the fact that this region is, well, maritime. Recent wars, including the Ukraine conflict, have shown how difficult it is to project force over oceans, and how comparatively cheap and easy it is for even a much weaker military force to prevent it.

So, the purely negative mission I would set for the Indonesia-Australia military pact is the ability to sink ships and down aircraft. … It’s not that a Chinese attack on either country is likely. But the chance to credibly threaten such an attack would colour every interaction with Beijing. Such threats need to be taken off the table to build a sustainable and constructive relationship with China. Yet at the same time, because Indonesia and Australia will always be weaker, they have no interest in threatening China or escalating a confrontation. A military strategy designed solely to nullify Chinese maritime power in Southeast Asia balances these tensions.

Buried beneath ground there are in fact 20 of these ancient rings in total — 95% of the site is yet to be excavated…

KONSTANTINA (KATE CONSTANTINE), '95714' 2024, $21,500

Orban, Europe and Putin

I'm a journalist, not a foreign policy analyst or political expert, but here’s my quick take on Orbán’s visit to Moscow: from his perspective, it’s a huge success. Orbán garnered all the attention he wanted, scored points with Putin and Trumpworld alike, and reaffirmed his position as the EU’s leading pro-Kremlin and anti-Ukrainian voice. This may also benefit him in the European Parliament, where he’s currently enticing MEPs and parties from other groups to join his Patriots for Europe faction.

Above all, Orbán has once again demonstrated that he can do whatever he wants. He got away with it again, just like when he held up Sweden’s NATO accession. Of course, there are many angry tweets from furious EU leaders and heads of member state governments – but why would he care? It’s all talk, no action, as it always has been, and Orbán knows this very well. The news cycle moves on, and since Hungary is still relatively "okay" compared to other troublemakers around the world, there will be no consequences.

When I talk to Hungarian government sources, this is usually their exact argument – besides the usual claim that “in secret, many countries actually support us; they’re just not allowed to say it out loud.” With all due respect to the decent EU leaders who publicly speak out against Orbán’s visit: they have actually enabled the Hungarian government's behavior since 2010. As a journalist, one of my favorite topics is investigating how Orbán successfully maneuvers in international politics, making backroom deals even with those who sometimes speak out against him. Whenever Orbán’s vote in the Council or NATO is needed, unimportant issues such as deteriorating rule of law and press freedom in Hungary are always swept aside.

There’s an EU infringement procedure here and there, with a final binding decision somewhere in the distant future – does Orbán care? Of course not. I’ve been covering Russian influence in Hungary for almost a decade, and I can only recall one instance where Viktor Orbán and his government gave up their pro-Russian stance. It was in April 2023, when the United States sanctioned the Russian-led International Investment Bank, dubbed the “Russian spy bank,” which Orbán had invited to be headquartered in Budapest and provided with diplomatic immunity.

Almost immediately after the US sanctions, the Hungarian government withdrew from the Russian “spy bank” as one of its shareholders and essentially expelled them from the country. No surprise there: Orbán doesn’t care about bad reputation, angry tweets, or diplomatic dressing-downs – he only cares about and fears real power. Orbán understands well that Putin is not afraid to use power, while Western players – such as the EU Commission or the US – only do so occasionally, like once in a decade. I'm pretty sure he thinks that now nobody will bother him until the early 2030s – especially if he can sit out this US administration and Trump returns to power in 2025 as he expects.

Edward Coles, human being

Residence: The nations of the righteous

The sources of the two letters are, respectively, here and here. The rest of the story is from this website.

From Edward Coles to Thomas Jefferson

Washington July 31st 1814

Dear Sir,

I never took up my pen with more hesitation or felt more embarrassment than I now do in addressing you on the subject of this letter. The fear of appearing presumptuous distresses me, and would deter me from venturing thus to call your attention to a subject of such magnitude, and so beset with difficulties, as that of a general emancipation of the Slaves of Virginia, had I not the highest opinion of your goodness and liberality, in not only excusing me for the liberty I take, but in justly appreciating my motives in doing so.

I will not enter on the right which man has to enslave his Brother man, nor upon the moral and political effects of Slavery on individuals or on Society; because these things are better understood by you than by me. My object is to entreat and beseech you to exert your knowledge and influence, in devising, and getting into operation, some plan for the gradual emancipation of Slavery. This difficult task could be less exceptionably, and more successfully performed by the revered Fathers of all our political and social blessings, than by any succeeding statesmen; and would seem to come with peculiar propriety and force from those whose valor wisdom and virtue have done so much in meliorating the condition of mankind. And it is a duty, as I conceive, that devolves particularly on you, from your known philosophical and enlarged view of subjects, and from the principles you have professed and practiced through a long and useful life, pre-eminently distinguished, as well by being foremost in establishing on the broadest basis the rights of man, and the liberty and independence of your Country, as in being throughout honored with the most important trusts by your fellow-citizens, whose confidence and love you have carried with you into the shades of old age and retirement. In the calm of this retirement you might, most beneficially to society, and with much addition to your own fame, avail yourself of that love and confidence to put into complete practice those hallowed principles contained in that renowned Declaration, of which you were the immortal author, and on which we bottomed our right to resist oppression, and establish our freedom and independence.

I hope that the fear of failing, at this time, will have no influence in preventing you from employing your pen to eradicate this most degrading feature of British Coloniel policy, which is still permitted to exist, notwithstanding its repugnance as well to the principles of our revolution as to our free Institutions. For however highly prized and influential your opinions may now be, they will be still much more so when you shall have been snatched from us by the course of nature. If therefore your attempt should now fail to rectify this unfortunate evil—an evil most injurious both to the oppressed and to the oppressor—at some future day when your memory will be consecrated by a grateful posterity, what influence, irresistible influence will the opinions and writings of Thomas Jefferson have on all questions connected with the rights of man, and of that policy which will be the creed of your disciples. Permit me then, my dear Sir, again to intreat you to exert your great powers of mind and influence, and to employ some of your present leisure, in devising a mode to liberate one half of our Fellow beings from an ignominious bondage to the other; either by making an immediate attempt to put in train a plan to commence this goodly work, or to leave human Nature the invaluable Testament—which you are so capable of doing—how best to establish its rights: So that the weight of your opinion may be on the side of emancipation when that question shall be agitated, and that it will be sooner or later is most certain—That it may be soon is my most ardent prayer—that it will be rests with you.

I will only add, as an excuse for the liberty I take in addressing you on this subject, which is so particularly interesting to me; that from the time I was capable of reflecting on the nature of political society, and of the rights appertaining to Man, I have not only been principled against Slavery, but have had feelings so repugnant to it, as to decide me not to hold them; which decision has forced me to leave my native state, and with it all my relations and friends. This I hope will be deemed by you some excuse for the liberty of this intrusion, of which I gladly avail myself to assure you of the very great respect and esteem with which I am, my dear Sir, your very sincere and devoted friend

Edward Coles

Thomas Jefferson to Edward Coles

Th. Jefferson seems to have had a very lax attitude to starting sentences with capital letters. I guess it was a generational thing.

Monticello Aug. 25. 14.

Dear Sir

Your favor of July 31. was duly recieved, and was read with peculiar pleasure. the sentiments breathed thro’ the whole do honor to both the head and heart of the writer. mine on the subject of the slavery of negroes have long since been in possession of the public, and time has only served to give them stronger root. the love of justice & the love of country plead equally the cause of these people, and it is a mortal reproach to us that they should have pleaded it so long in vain, and should have produced not a single effort, nay I fear not much serious willingness to relieve them & ourselves from our present condition of moral and political reprobation. from those of the former generation who were in the fulness of age when I came into public life, which was while our controversy with England was on paper only, I soon saw that nothing was to be hoped. nursed and educated in the daily habit of seeing the degraded condition, both bodily & mental, of those unfortunate beings, not reflecting that that degradation was very much the work of themselves & their fathers, few minds had yet doubted but that they were as legitimate subjects of property as their horses or cattle. the quiet & monotonous course of colonial life had been disturbed by no alarm, & little reflection on the value of liberty. and when alarm was taken at an enterprise on their own, it was not easy to carry them the whole length of the principles which they invoked for themselves. in the first or second session of the legislature after I became a member, I drew to this subject the attention of Colo Bland, one of the oldest, ablest, and most respected members, and he undertook to move for certain moderate extensions of the protection of the laws to these people. I seconded his motion, and, as a younger member, was more spared in the debate: but he was denounced as an enemy to his country, & was treated with the grossest indecorum. from an early stage of our revolution other and more distant duties were assigned to me, so that from that time till my return from Europe in 1789. and I may say till I returned to reside at home in 1809. I had little opportunity of knowing the progress of public sentiment here on this subject. I had always hoped that the younger generation, recieving their early impressions after the flame of liberty had been kindled in every breast, and had become as it were the vital spirit of every American, that the generous temperament of youth, analogous to the motion of their blood, and above the suggestions of avarice, would have sympathised with oppression wherever found, and proved their love of liberty beyond their own share of it. but my intercourse with them, since my return, has not been sufficient to ascertain that they had made towards this point the progress I had hoped. your solitary but welcome voice is the first which has brought this sound to my ear; and I have considered the general silence which prevails on this subject as indicating an apathy unfavorable to every hope. yet the hour of emancipation is advancing in the march of time. it will come; and whether brought on by the generous energy of our own minds, or by the bloody process of St Domingo, excited and conducted by the power of our present enemy, if once stationed permanently within our country, & offering asylum & arms to the oppressed, is a leaf of our history not yet turned over.

As to the method by which this difficult work is to be effected, if permitted to be done by ourselves, I have seen no proposition so expedient on the whole, as that of emancipation of those born after a given day, and of their education and expatriation at a proper age. this would give time for a gradual extinction of that species of labor and substitution of another, and lessen the severity of the shock which an operation so fundamental cannot fail to produce. the idea of emancipating the whole at once, the old as well as the young, and retaining them here, is of those only who have not the guide of either knolege or experience of the subject. for, men, probably of any colour, but of this color we know, brought up from their infancy without necessity for thought or forecast, are by their habits rendered as incapable as children of taking care of themselves, and are extinguished promptly wherever industry is necessary for raising the young. in the mean time they are pests in society by their idleness, and the depredations to which this leads them. their amalgamation with the other colour produces a degradation to which no lover of his country, no lover of excellence in the human character can innocently consent.

I am sensible of the partialities with which you have looked towards me as the person who should undertake this salutary but arduous work. but this, my dear Sir, is like bidding old Priam to buckle the armour of Hector ‘trementibus aevo humeris et inutile ferrum cingi.’ [translation: “with shoulders trembling from age and girded with useless iron (weapons/sword)”] no. I have overlived the generation with which mutual labors and perils begat mutual confidence and influence. this enterprise is for the young; for those who can follow it up, and bear it through to it’s consummation. it shall have all my prayers, and these are the only weapons of an old man. but in the mean time are you right in abandoning this property, and your country with it? I think not. my opinion has ever been that, until more can be done for them, we should endeavor, with those whom fortune has thrown on our hands, to feed & clothe them well, protect them from ill usage, require such reasonable labor only as is performed voluntarily by freemen, and be led by no repugnancies to abdicate them, and our duties to them. the laws do not permit us to turn them loose, if that were for their good: and to commute them for other property is to commit them to those whose usage of them we cannot controul. I hope then, my dear Sir, you will reconcile yourself to your country and it’s unfortunate condition; that you will not lessen it’s stock of sound disposition by withdrawing your portion from the mass. that, on the contrary you will come forward in the public councils, become the Missionary of this doctrine truly Christian, insinuate & inculcate it softly but steadily thro’ the medium of writing & conversation, associate others in your labors, and when the phalanx is formed, bring on & press the proposition perseveringly until it’s accomplishment. it is an encoraging observation that no good measure was ever proposed which, if duly pursued, failed to prevail in the end. we have proof of this in the history of the endeavors in the British parliament to suppress that very trade which brought this evil on us. and you will be supported by the religious precept ‘be not wearied in well doing.’ that your success may be as speedy and compleat, as it will be of honorable & immortal consolation to yourself I shall as fervently & sincerely pray as I assure you of my great friendship and respect.

Th: Jefferson

Edward Coles frees his slaves, Governs Illinois

In his response, Coles mildly rebuked Jefferson for using age as an excuse for inaction. He reminded the great sage that Benjamin Franklin had undertaken arduous duties at an older age. Coles depressingly reiterated that only an elder of Jefferson's influence could lead public opinion in such a fashion that emancipation would be palatable.

Coles could not rest without acting to free his slaves, and removing to the Northwest Territory seemed his only option. He did not feel he possessed the talent or influence to lead an emancipation crusade; his only recourse was to leave "the scene of.... oppression." Deciding finally to relocate, Coles traveled to the West in the summer of 1815. He found land in Ohio prohibitively expensive and Indiana too rough in country and people. He went to Illinois and found acceptable the bottomland (American Bottom) along the Mississippi River near present-day St. Louis, Missouri. He purchased six thousand acres in Madison County. Back in the East, Coles could not disengage himself from the Madison administration. The president appointed his young secretary as a special envoy to Russia. Coles was charged to restore friendly relations with the czarist regime, strained after a Russian diplomat was imprisoned for rape in Philadelphia. Coles accepted and arrived in Russia in September 1816. His mission was a success, the czar was appeased, and Coles traveled through Europe enjoying the sights.

After his return to the United States, Coles secured an appointment as a land registrar from the new president, James Monroe. He traveled to Illinois again in the summer of 1818 and made final arrangements for his relocation. In April 1819, Coles started his slaves on the road to the new state of Illinois. He purchased flatboats, and the party drifted down the Ohio River. Coles excitedly believed that the time had arrived to carry into effect the plan his conscience had so long desired.He gathered his slaves together on deck in the sunlight of a beautiful spring morning. He announced that the slaves were free and could go with him to Illinois or not as they saw fit. "In breathless silence they stood before me, unable to utter a word, but with countenances beaming with expression which no words could convey, and which no language can now describe. As they began to see the truth of what they had heard, and to realize their situation, there came on a kind of hysterical, giggling laugh," Coles remembered with pleasure. The newly freed slaves thanked Coles for his kindness and with the extraordinary generosity of spirit, insisted that they accompany their former master to Illinois to get Coles's new farm in working order. Once in Illinois, Coles gave each of his former slaves 160 acres of land on which to begin their lives anew as yeomen farmers.

Coles worked as a land registrar in Edwardsville for three uneventful years before he turned to politics. In September 1821, Coles declared as a candidate for governor of Illinois; the election was to be held in August 1822. At the time, politics in Illinois was organized into factions gathered about certain political figures, men like Ninian Edwards and Shadrach Bond. Coles was not a member of any faction. He simply announced his candidacy in the fashion of the day. His opponents included two justices of the Illinois Supreme Court, Thomas C. Browne and Joseph Phillips, and a somewhat obscure military veteran, James B. Moore. Phillips was identified with Bond, Browne with Edwards. Coles was elected with a total vote of a little more than half the combined vote of Phillips and Browne.

Once in office as governor, Coles quickly faced a movement to call a constitutional convention to rewrite the Illinois constitution, approved only four years previous. The not-so-veiled purpose of the effort was to make Illinois a slave state. Slavery had been introduced into the territory that became the state of Illinois in the eighteenth century. It had continued to exist in the nineteenth century despite the Northwest Ordinance's prohibition against it. The successful salt works near Shawneetown had even spurred the introduction of additional slaves into the state. A harsh black code had been instituted in 1819 to govern the black population, a set of laws as odious as any promulgated[2] in the slaveholding South. In his inaugural address as governor, Coles had bluntly called for an end to slavery in Illinois and for a humane revision of the black code. His bold announcement may have prompted the proslavery forces in Illinois to work for the convention. It required a two-thirds majority in the state legislature to enact a referendum on whether to convene a constitutional convention. In order to secure that majority, a substantial amount of arm twisting occurred in the legislature, including the unseating of an anti-convention representative with a convention supporter. Coles remarked on the "extraordinary malevolence of party spirit" the issue engendered in Illinois.

Coles recognized that he was at the center of intense controversy on the most difficult political question of the age. He ruefully reflected: "Whatever may be the result of this question, it will certainly have the effect of giving me a very stormy time of it as long as I shall be at the helm." Coles's assessment was accurate. He became the de facto leader of the antislavery forces in the state who opposed the convention movement. In consequence, he was roundly abused in the press and on the stump. Proslavery ruffians marched to his home and shouted insults in the middle of the night. Coles was sued for allegedly violating Illinois law in the release of his slaves. Though the suit was eventually dismissed, Coles had to endure lengthy litigation.

For two long years, the convention question gripped the Illinois populace. Coles was deeply engaged in the struggle. He concluded that it was "necessary that the public mind should be enlightened on the moral and political effects of slavery." He wrote to his Philadelphia friends for antislavery tracts and then distributed them in Illinois at his own expense. He did his own research and writing on the issue, publishing antislavery articles under pseudonyms in the Illinois newspapers. He purchased a part interest in a newspaper to get his message out. He sent antislavery pamphlets and information to others for their use in writing antislavery letters to the press and public. Coles's efforts were successful. In a statewide vote on August 2, 1824, the convention was defeated.

For the remainder of his gubernatorial term, Coles advocated internal improvements, sound banking, and reform of the Illinois Black Code. After retiring from office, he became active in the colonization movement, an effort to relocate freed slaves to Africa. He ran unsuccessfully for Congress in 1830, his campaign hampered by the perception that he was not a permanent resident in Illinois. He confirmed the accuracy of that assessment by moving to Philadelphia. He became a Whig and an opponent of the Jackson administration but took little active part in politics. Coles married Sally Logan Roberts in 1833. He died in Philadelphia in 1868.