Education as a frozen lake

And other highlights of one week on the internet in the pre-armageddon era

Well, it took the Beatles until 1967 to invent the concept album, but this is a concept newsletter. I doubt this will last, but last week’s concept was Civilisation and this weeks’s is Education. And how glacially it moves.

Freakonomics: Quirky, rigorous, cute, trivial?

Alas, I was never much of a fan. But Levitt was a clever fellow and it was fun to see the things he turned up. If I had more time, I’d say more about what a great economist Heckman is, but how his work still shows how much economists have to be humble about. I don’t mean that in any snide way. The fact is that, when it comes to human affairs, technical mastery is important, but its ability to illuminate our path is modest. That’s a lesson that another great economist and Nobel laureate, Ben Bernanke hasn’t quite learned. But more about that in a coming newsletter!

Economics is a science with excellent tools for gaining answers but a serious shortage of interesting questions.

Steve Levitt, 2003

Freakonomics was a hit. It ranked just below Harry Potter in the bestseller lists. … It was at the apex of a wave of books that promised a quirky—yet rigorous—analysis of things that the conventional wisdom had missed. On March 7th Mr Levitt, who for many people became the image of an economist, announced his retirement from academia. “It’s the wrong place for me to be,” he said.

During his academic career, Mr Levitt wrote papers in applied microeconomics. He was, in his own self-effacing words, “a footnote to the ‘credibility revolution’”. This refers to the use of statistical tricks, such as instrumental-variable analysis, natural experiments and regression discontinuity, which are designed to tease out causal relationships from data. He popularised the techniques of economists including David Card, Guido Imbens and Joshua Angrist, who together won the economics Nobel prize in 2021. The idea was to exploit quirks in the data to simulate the randomness that actual scientists find in controlled experiments. Arbitrary start dates for school terms could, for instance, be employed to estimate the effect of an extra year of education on wages.

Where the Freakonomics approach differed was to apply these techniques to “the hidden side of everything”, as the book’s tagline put it. Mr Levitt’s work focused on crime, education and racial discrimination. The book’s most controversial chapter argued that America’s nationwide legalisation of abortion in 1973 had led to a fall in crime in the 1990s, because more unwanted babies were aborted before they could grow into delinquent teenagers. It was a classic of the clever-dick genre: an unflinching social scientist using data to come to a counterintuitive conclusion, and not shying away from offence. It was, however, wrong. Later researchers found a coding error and pointed out that Mr Levitt had used the total number of arrests, which depends on the size of a population, and not the arrest rate, which does not. Others pointed out that the fall in homicide started among women. No-fault divorce, rather than legalised abortion, may have played a bigger role.

Other economists, including James Heckman, Mr Levitt’s colleague in Chicago and another Nobel prizewinner, worried about trivialisation. “Cute”, was how he described the approach in one interview. Take a paper on discrimination in the “The Weakest Link”, a game show in which contestants vote to remove other contestants depending on whether they think they are costing them money by getting questions wrong (in the early portion of the game) or are competition for the prize pool by getting them right (later on). That provided a setting in which Mr Levitt could look at how observations of others’ competence interacted with racism and sexism. A cunning design—but perhaps of limited relevance in understanding broader economic outcomes.

At the heart of Mr Heckman’s critique was the idea that practitioners of such studies were focusing on “internal validity” (ensuring estimates of the effect of some change were correctly estimated) over “external validity” (whether the estimates would apply more generally). Mr Heckman instead thought that economists should create structural models of decision-making and use data to estimate the parameters that explained behaviour within them. The debate turned toxic. According to Mr Levitt, Mr Heckman went so far as to assign graduate students the task of tearing apart the Freakonomics author’s work for their final exam.

Neither man won. The credibility revolution ate its own children: subsequent papers often overturned results, even if, as in the case of those popularised by Freakonomics, they had an afterlife as cocktail-party anecdotes. The problem has spread to the rest of the profession, too. A recent study by economists at the Federal Reserve found that less than half of the published papers they examined could be replicated, even when given help from the original authors. Mr Levitt’s counterintuitive results have fallen out of fashion and economists in general have become more sceptical.

Yet Mr Heckman’s favoured approaches have problems of their own. Structural models require assumptions that can be as implausible as any quirky quasi-experiment. Sadly, much contemporary research uses vast amounts of data and the techniques of the “credibility revolution” to come to obvious conclusions. The centuries-old questions of economics are as interesting as they always were. The tools to investigate them remain a work in progress.

Australia Post’s magic tricks can fool some of the people, some of the time

Can it do more?

Will Australia Post be able to con nearly everyone? Find out in this exciting podcast — Leon Gettler’s interview with me. The interview starts at 13.50 in his Talking Business podcast above. Or immediately in my own podcast below.

Or you can play the segment directly from Substack here.

Data science in schools? Surely not?

Over a decade ago now, as I ponced on about innovation in education, I was brought short with the thought that my kids’ maths curriculum was exactly the same as it had been when I was a kid. Trig was in. Stats was out. Not that I have anything against trig. It was fun to learn. But we don’t mainly need to triangulate the height of flagpoles these days whereas stats and data science are fundamental to the fabric of our lives. Anyway, trig is still in and stats and data science are still out. It’s pretty extraordinary how utterly inert the system is in responding to things on the educational merits (as opposed to incorporating the latest excitements from the politico-entertainment complex).

Anyway, sure enough, data science in schools has managed to get a guernsey in the American education debate via the ‘inclusivity’ agenda. The NYT takes up the story:

After faculty protests and a debate over racial equity, the state’s public universities reconsider whether high school students can skip a foundational course.

Since 2020, California has led a contentious experiment in high school math.

That year, public universities in the state — including Berkeley and U.C.L.A. — loosened their admissions criteria, telling high schools that they would consider applicants who had skipped Algebra II, a cornerstone of math instruction.

In its place, students could take data science — a mix of math, statistics and computer science without widely agreed upon high school standards. Allowing data science, the universities said, was an “equity issue” that could send more students to college. But it also raised concerns that some teenagers would be channeled into less challenging coursework, limiting their opportunities once they got there.

Now, the California experiment is under review.

On Wednesday, the State Board of Education voted to remove its endorsement of data science as a substitute for Algebra II as part of new guidelines for K-12 schools.

“We have to be careful and deliberate about ensuring rigor,” Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the state board, said before the vote.

The push for data science is also complicated by the wide racial disparities in advanced math, especially in calculus, which is a prerequisite for most science and math majors. In 2019, 46 percent of Asian high school graduates nationally had completed calculus, compared with 18 percent of white students, 9 percent of Hispanic students and 6 percent of Black students, according to a 2022 study by the National Center for Education Statistics.

“Many educators are justifiably concerned that the calculus pathway institutionalizes racial inequities by decreasing the number of Black and Latino students in college,’’ Robert Gould, the author of a high school data science course, wrote in a 2021 article. Data science courses, he suggested, connect students’ everyday lives to their academic careers, “which one hopes will lead to a more diverse university enrollment.’’

But in a May 2022 letter to the U.C. faculty senate committee, eight Black faculty members argued that data science courses “harm students from such groups by steering them away from being prepared for STEM majors.”

Gettysburg: an interpretation

Steven Levitt on data science in school

At which point, Steven Levitt took up the cudgels.

The three-year battle over California’s new math framework has produced calamity and confusion on all fronts. As fighting raged across op-ed pages and Twitter, the fog of war obscured the inescapable truth: The data revolution is here and our kids are not prepared for it.

From ChatGPT to personal finance, nearly every decision we make in our daily lives is now dominated by data. Eight out of ten of the fastest-growing careers this year involve data science. A decade from now, it will be difficult to find any job that is not data-driven.

We need to equip our students for this new reality by teaching them basic data literacy in K-12. We can all see this, but somehow the politics of the moment have turned this idea into a raging debate.

The new critics of data science instruction seem to have three common objections. Their first claim is that data science programs are somehow “watering down” math. That is indeed possible, especially if districts treat data-related classes as a form of remediation, but this should not be the case. Data science is a very challenging subject, combining traditional math, statistics, computer programming, and complex datasets. In many ways, it demands more of students, requiring critical thinking, creativity, and a nuanced understanding of the context within which data have been generated.

A second objection is that learning data science in high school is somehow illegitimate because students won’t yet have the mathematics skills required of professional data scientists. This is an odd argument. Can high school students never learn anything about physics because they don’t understand differential calculus? Can they not find beauty in a Shakespearean sonnet if they don’t know the rules of iambic pentameter?

The third claim is that data science coursework will crowd out calculus or some of the other math required for college STEM degrees. This is an important concern, but it assumes that every part of today’s curriculum is absolutely critical to that path. Do we really think that is true? Having spent many nights at the kitchen table helping my kids with their homework, I suspect it’s not. And we (parents) shouldn’t ignore the more than 130 college disciplines that now require data and statistics basics as the world changes–including math and engineering.

Let’s put down our weapons in this math war and start fighting again for our kids’ futures.

Jane Price: lovely Australian painter who got about with the folks from the Heidelberg School

More images here.

Journalism on death row

Wonderful profile in the New Yorker in which one inmate in America’s gulag interviews another who survived 12 years on death row before having his sentence commuted to life imprisonment. He founded a prison magazine.

What was the first book you read on death row?

“Fairoaks ,” by Frank Yerby—a plantation novel. I was totally shocked that something like this existed, because, you have to understand, the world I came from didn’t teach slavery to the students.

The first time you learned about slavery was reading Frank Yerby on death row?

On death row!

In your memoir, you wrote that reading allowed you “to emerge from my cocoon of self-centeredness and appreciate the humanness of others—to see that they, too, have dreams, aspirations, frustrations, and pain. It enabled me finally to appreciate the enormity of what I had done, the depth of the damage I had caused others.”

It’s why I’m such a pro-book person. It’s exposure to other perspectives, to other lives, to other beings, to other worlds.

You grew up in Lake Charles, Louisiana.

It was the Deep South—a totalitarian regime that was all about white men. As far as criminal justice goes, let me hip you to something. You’re a prisoner, and you’ve been through the system. But I come from a world before Gideon v. Wainwright. You didn’t have a right to an attorney. You didn’t have a right to anything except to complain, to pray, and maybe to die. At a certain point, because of Emmett Till and sensational stuff that was disturbing the country, they decided that lynching Black folks was bad for their public image. So they transferred what they were doing from the tree and the rope to the courtroom. In 1961, I was a product of that world. I was frustrated. I was angry.

At nineteen, you probably couldn’t wrap your head around all this.

I was really, really ignorant. I didn’t even know who the hell the governor was. And the crime, even in my own opinion, was really stupid. I tried to rob a bank, it got out of hand, and I panicked. I was scared. One of the tellers ended up dead. I killed her. I’m responsible for that.

Eight weeks later, I was tried by a jury of all white men, and in an hour they came back with a verdict of death. The United States Supreme Court threw out the death sentence, called it a kangaroo-court proceeding. In 1964, twelve white men again found me guilty and gave me the death penalty, in fifteen minutes. In 1970, a federal court threw that conviction out, too. And again, twelve white men found me guilty, this time in eight minutes. Three juries with all white men, in a state where half the people are women, and a third of the population was Black. That was justice back then. That’s why they called it “lynch law.”

I mean, we’re all so ignorant when we come to prison.

And a lot of us grow up like a weed in the crack in the sidewalk someplace—untended, unguided. Just on its own. That’s asking for trouble. I mean, the fact that some of us turn out to be a beautiful flower, that’s a miracle.

Forecasting as performance art

Andy Haldane on Bernanke on Bank of England forecasting

We interrupt this concept album on education to bring you the snappiest, best-informed op-ed of the week. One way you can tell is from how little I was able to edit out without detracting from the flow and the argument. From Andy Haldane, my favourite civil servant in all the world, until he became my favourite former civil servant in all the world — when he left the Bank of England a few years ago to head up the RSA.

In the early years of inflation targeting in the UK, the then head of forecasting at the Bank of England entered my room clutching a piece of paper. On it were two lines: the inflation forecast produced painstakingly by his team over the preceding weeks, and an alternative inflation projection hand-drawn in pencil by the then governor. Only the latter “forecast” ever saw the light of day.

Since then, governors and monetary policymakers have come and gone, each bearing different pencils. But the process of economic forecasting has remained essentially unchanged: largely performative, typically opaque, nine parts art to one part science. The recent review of forecasting by Ben Bernanke, former chair of the US Federal Reserve, while full of sound recommendations, is unlikely to alter that.

It was all meant to be so different. At the outset of inflation targeting, the use of inflation forecasts was deemed a breakthrough. The long and variable lags of monetary policy mean it is only by responding to inflation one-two years ahead that timely decisions can be made about interest rates today. Inflation forecasts became the pivot point for monetary policy.

The second breakthrough was to have those projections produced, consistently and coherently, courtesy of an economic model. This served as a disciplining device on the whims of policymakers. In that sense, inflation forecasting was a key constraint in the “constrained discretion” of inflation targeting. Future inflation is of course uncertain.

Former central bank governor Mervyn King used to observe that the probability of forecasts proving correct was almost precisely zero. (Ironically, this is one of the few BoE forecasts ever made that turned out to be accurate.) …

Full disclosure, there was no more effusive advocate of this new monetary policy technology than me. And inflation targeting itself has performed far better than anyone could ever have expected in anchoring inflation expectations. But, truth be told, inflation forecasting has been incidental to this success.

This is not (or not only) because models and their forecasts have been wrong, often very wrong. That comes with the territory. It is because inflation forecasting has in practice imposed the wrong sorts of policy constraint. Economic models bring rigour to policy. Unfortunately, they also bring mortis.

Even models at the frontier are always at least one step behind real-world events: from the global financial crisis (when most were found to take no meaningful account of the financial sector) to the Covid-19 and cost of living crises (when most were found to have no well-developed sectoral supply side). In these instances, models served to unhelpfully blinker policymakers to events playing out before their eyes, but not embedded in their models. This led to them first missing these crises, and then responding too slowly.

Those models can also be gamed in ways that impose too few constraints on policy. In my experience, many policymakers produced their economic forecasts by working backwards from their preferred stance. This is an inversion of the way inflation targeting was meant to operate.

Bernanke’s diagnosis and recommendations are sound. The bank’s fans, like those in a fan dance, were used largely to preserve the dignity of the dancer and avoid audience embarrassment. Their suggested replacement, with defined scenarios, will deliver a more revealing performance, while still leaving the audience largely in the dark. …

John Kenneth Galbraith famously said economics was extremely useful — as a method of employment for economists. The same could be said of inflation forecasts and central bankers. For all Bernanke’s sound analysis, forecasting is likely to remain interpretive dance — always mysterious, occasionally enlightening, a show without much tell.

Structure dear boy; structure

Events dear boy: events.

PM Harold Macmillan on the greatest challenge for a statesman

In my initial commentary above I linked to a column of mine from 2012. Then I thought I’d include it here.

IN 2010 the energetic and forward-looking (then) secretary of Victoria’s Education Department invited me to discuss educational innovation and Web 2.0 with senior departmental managers.

We spoke about the worlds of activity for students opening up from the free resources burgeoning on the web – such as doing historical research while they correct text errors from Australia’s historical newspapers on Australia’s National Library newspaper digitisation website. Or mashing up details of their local environment on Google Maps. Or helping optimise the school timetable with open-source tool FET.

But that’s just kids’ stuff. The web and social media can take students to the forefront of science. They can classify distant objects on NASA’s Galaxy Zoo. Or play Foldit, a dangerously addictive computer game that you win by finding the cleverest ways to fold toy proteins on the screen. Competitors on Foldit have already helped uncover the structure of an AIDS-causing monkey virus and more besides.

Despite this explosion of possibilities, as my children have gone through school I’ve been amazed at how, if you strip off the various genuflections to political correctness, so much of the curriculum is unchanged from the one I completed decades ago.

Shouldn’t we be using such things as spreadsheets not just as occasional tools for computation but like blackboards – as a ubiquitous pedagogical vehicle for students to visualise the maths they’re learning. Wouldn’t stats and data science be more useful than, say, trigonometry? Shouldn’t students get some familiarity with computer languages at least as electives within maths or languages curriculums? After all, building unambiguous instructions to a computer to execute complex tasks is as demanding, as rewarding and enlightening as learning French or Chinese.

I remember the shared enthusiasm around the table. And I remember saying something like this: ”Some upskilling and recruiting of specific teaching skills is necessary. But access students’ skills. Rather than discouraging the best and brightest students with group work in which the more opportunistic students prey upon their enthusiasm, find ways to make the space and give the credit necessary for students who know this stuff already to mentor others – not least by reverse-mentoring teachers.”

It seemed like a good idea, but how to make it happen? I suggested it should start small and grow. A few months later the departmental secretary invited me to attend Listen2Learners, which celebrated students’ achievements in Web 2.0 projects. There I met Ben, a year 8 student who had built a simple iPhone app to help hone his older brother’s mental arithmetic skills. After asking Ben how he found year 9 maths (Boring! We keep doing the same stuff), I asked how he would like to teach other students how to write iPhone apps (Awesome!). Then I told him to wait right there. I introduced Ben to the departmental secretary, who called his innovation officer over and emphasised: ”Let’s start on this tomorrow!”

At the beginning of the next year I emailed Ben and asked him what had happened. I still have his reply: ”Nothing really went anywhere with my school, didn’t really surprise me.”

Today the secretary and his innovation officer have moved on. So has Ben.

I didn’t write this column to suggest that nothing’s happening, or to belittle theirs or anyone else’s efforts. But it does underline how heavy the tyranny of existing routines can be. My guess is that most people in the system liked the idea, but there were no specific programs or routines that could be ”pegs” on which to hang Ben’s mentoring other students. Which rooms would he use? Whose class would he miss?

[Structure, dear boy. Structure!]

Innovation is almost invariably fragile in existing institutions. Of course it takes leadership from the top, rather than slogans. But even then Ben’s story shows us that innovation cannot thrive unless there are enough people within the system prepared to endure discomfort of varying existing routines, with the courage to experiment and risk failure and the perseverance to learn from mistakes even while the opposition of the day and the media will be waiting to pounce on any slip.

But don’t fear for Ben. He left high school last year for home schooling. He will have a double degree from the Open University of Australia in IT and business by mid-next year. (He would have been midway through year 11.) Then he’ll be taking on the world. So at the macro level our education system was pluralistic enough to work, even though other school students missed out on what Ben had to offer them.

Still, the web is barely two decades old. I’m optimistic that it won’t be too long before our schools gorge themselves more fully on the embarrassment of riches that lies before them in the vast and ever growing expanses of cyberspace.

Structure dear boy; structure II

Here’s a discussion paper I wrote for the board of The Australian Centre for Social Innovation (TACSI) concerning the failure of our brilliant Family by Family program to ‘scale’ as they say. I publish this extract apropos of the same situation regarding education.

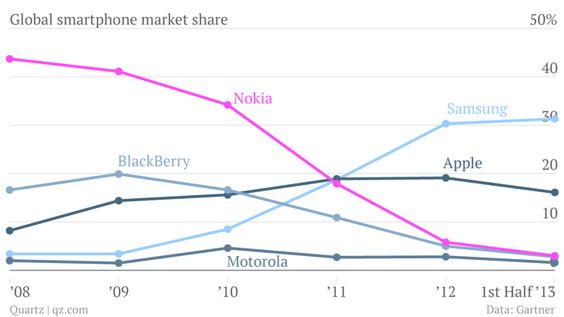

Consider the introduction of the iPhone. On its release, few believed it was a major step forward – including industry experts. It involved no major technological advance. Rather it improved the interface between the user and the machine. Yet there was a surge in demand for the iPhone and phones powered by Apple’s fastest follower – Google’s Android operating system. Like most self-respecting centrally planned organisations, other smartphone producers like Nokia and Blackberry had plans to expand their business. But in a tolerably functioning market, they couldn’t sustain those expansions and were soon forced to cut production. As a result the market ‘miraculously’ restructured towards superior technology.

Within a centrally planned system none of these changes happen spontaneously. Imagine a new and in some way superior method of remedial teaching emerges in a state school. It might sit unremarked and even unnoticed by the managers of the host school. If it is noticed, the administrators of the school or even the district won’t necessarily regard it as their role to spread the word. They are unlikely to be funded to do so.

But assuming the new approach is promoted locally, how far will it spread? Career incentives for those in the centrally planned system are not typically set to reward those who detect such improvements, to resource administrators to spread them or to defund less successful approaches. If the improvement does spread, there will be interests within the system that remain at best indifferent, if not actively hostile to the discomfort that spreading the system would entail. Further, the new approach might emerge from some difference in sensibility – which may mean that if the approach is to spread, it will need to be spread by people with that sensibility. Yet the insiders already in the system will likely have the strongest claims to be employed rolling out the new system – irrespective of their aptitude to do so. That fact alone may vitiate the effectiveness of extending the innovation beyond its origins. …

In short, FACS cannot optimise its performance by simply choosing the optimal allocation between different programs. Programs produce complex and interrelated outputs. Thus if the Family by Family offers superior performance, FACS will not have the funds to simply roll it out wherever it would generate substantial benefits. It must go through a much more involved process of both prioritising its funding – defunding some things to increase funding on others – and reshaping routines and programs so as to knit together their resulting impacts as best they can. Even understanding precisely what should happen is far from easy, but even if it were, the fact is that organisations typically find the necessary reorientation of operations immensely difficult.

And all this is within the portfolio department’s own domain. Yet there are compelling opportunities for both the TACSI methodology and the Family by Family program to deliver outcomes of greater significance further afield. If Family by Family is as successful as it seems to be, it is likely it could have powerful impacts in improving educational outcomes, mental health and correctional services to name just three areas. How can we build a strategy to:

explore and generate evidence regarding this possibility and (if that evidence is compelling)

provide an conceptual and organisational road map to expand the program in the optimal way to Extend, Connect and Transform

This is explored in the next section. …

And so on. Thing is, the vast amount of dollars and column inches expended on innovation don’t spend much time grappling with these problems. But at least I do have a slogan I’d like people to take more seriously.

It’s not ‘What works’, but ‘who made it work’.

Do feel free to help me propagate it.

Fruitcake watch

Filed under boxers keen on Austrian economics

And for context, neoliberal godfather Ludwig von Mises knew whose side he was on in 1927.

"It cannot be denied that Fascism and similar movements aiming at the establishment of dictatorships are full of the best intentions and that their intervention has, for the moment, saved European civilization. The merit that Fascism has thereby won for itself will live on eternally in history. But though its policy has brought salvation for the moment, it is not of the kind which could promise continued success. Fascism was an emergency makeshift. To view it as something more would be a fatal error."

Terry Eagleton on power and culture

I didn’t expect much from this essay as Eagleton tosses off essays in all directions. Like his bio says “Terry Eagleton has written around fifty books.” But it gave me much food for thought.

What else was happening around the time of Romanticism and the industrial revolution? The revolution in France. One might do worse than claim that this was what thrust culture to the fore in the modern age – but culture as a riposte to the revolution, as an antidote to political turbulence. Politics involves decision, calculation, practical rationality, and takes place in the present, whereas culture seems to inhabit a different dimension, where customs and pieties evolve for the most part spontaneously, unconsciously, with almost glacial slowness, and may therefore pose a challenge to the very notion of throwing up barricades.

The name for this contrast in Britain is Edmund Burke, who came from a nation, Ireland, where the sovereign power had failed to root itself in the affections of the people because it was a colonialist power. In Burke’s view, this rooting wasn’t happening in revolutionary France either, since the Jacobins and their successors didn’t understand that if the law is to be feared, it is also to be loved. What you need in Burke’s opinion is a law which, though male, will deck itself out in the alluring female garments of culture. Power must beguile and seduce if it isn’t to drive us into Oedipal revolt. The potentially terrifying sublimity of the masculine must be tempered by the beauty of the feminine; this aestheticising of power, Burke writes in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, is what the French revolutionaries calamitously failed to achieve. You mustn’t, to be sure, aestheticise away the masculinity of the law. The ugly bulge of its phallus must be visible from time to time through its diaphanous robes, so that citizens may be suitably cowed and intimidated when they need to be. But the law can’t work by terror alone, which is why it must become a cross-dresser.

Burke believed that the cultural domain – the sphere of customs, habits, sentiments, prejudices and the like – was fundamental in a way that the politics to which he devoted a lifetime were not, and he was right to think so. There have been some suspect ways of elevating the cultural over the political, but Burke, who began his literary career as an aesthetician, neither despises politics from the Olympian standpoint of high culture, nor dissolves politics into cultural affairs. Instead, he recognises that culture in the anthropological sense is the place where power has to bed itself down if it is to be effective. If the political doesn’t find a home in the cultural, its sovereignty won’t take hold. You don’t have to detest the Jacobins or idealise Marie Antoinette to take the point.

Despite his aversion to Jacobinism, Burke ended up feeling some sympathy for the revolutionary United Irish movement, an extraordinary sentiment for a British Member of Parliament. The Irish playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, also an MP, was even more dedicated to the United Irish cause. He was, in fact, a secret fellow-traveller – a fact that, had it been widely known, might have wiped the smiles off the faces of his London audiences. The United Irishmen were Enlightenment anti-colonialists, not Romantic nationalists, but the rise of Romantic nationalism in the early 19th century once more brought culture to the centre of political life.

Nationalism was the most successful revolutionary movement of the modern age, toppling despots and dismantling empires; and culture in both its aesthetic and anthropological senses proved vital in this project. With revolutionary nationalism, culture in the sense of language, custom, folklore, history, tradition, religion, ethnicity and so on becomes something people will kill for. Or die for. Not many people are prepared to kill for Balzac or Bowie, but culture in this more specialised sense also plays a key role in nationalist politics. There are jobs for artists once more, as from Yeats and MacDiarmid to Sibelius and Senghor they become public figures and political activists. In fact, nationalism has been described as the most poetic form of politics. …

The nation itself resembles a work of art, being autonomous, unified, self-founding and self-originating. As this language might suggest, both art and the nation rank among the many surrogates for the Almighty that the modern age has come up with. Aesthetic culture mimics religion in its communal rites, priesthood of artists, search for transcendence and sense of the numinous. If it fails to replace religion, this is, among other things, because culture in the artistic sense involves too few people, while culture in the sense of a distinctive way of life involves too much conflict. No symbolic system in history has been able to rival religious faith, which forges a bond between the routine behaviour of billions of individuals and ultimate, imperishable truths. It’s the most enduring, deep-rooted, universal form of popular culture that history has ever witnessed, yet you won’t find it on a single cultural studies course from Sydney to San Diego.

World fairs!

Girls just wanna have fun, conservatives just wanna be radical

This is a shoot-out between two Apex conservatives in the US. Curtis Yarvin knows a lot of history and is quite insightful about what is wrong. Then again we shouldn't really use the word ‘conservative’, because conservatives haven’t been very conservative for some time.

Like lots of radicals, Yarvin is a nightmare when it comes to what he wants to do. A model of the intellectual’s impatience and grandiosity. He wants a monarchy or tyranny depending on how it turns out — because monarchs can be held to account — no I’m not joking — though it’s hard to believe he isn’t.

And he’s stoushing with Christopher Rufo, who is a very effective right-wing activist who does culture war set-ups like the one that did for Claudine Gay. Our two right-wingers seem to have contempt for each other. Here are a few snippets of a long series of exchanges to whet your appetite. They barely make contact with each other, which is not usually my thing, but somehow I found it intriguing. And it’s usually good to keep your eye on what the bad guys are up to.

HT: A reader who drew my attention to the exchange and then, on my asking about the website, turned up this profile of the website and Rufo.

Yarvin: A conservative is someone who thinks our national story has gone off the rails. … Everything is in slow motion. He cannot avoid the feeling that he is no longer traveling into the future – but plunging, terribly, into some unfathomable ravine.

If you are a conservative, whether you have asked yourself this specific question or not, you must have some idea of (a) when our country went off the rails, (b) how far we are from those rails, and (c) what kind of political force would be required to get us back on track. …

I am not a conservative. I am a radical – a radical monarchist. I believe there are no rails – and never were any. America has no manifest destiny. Her constitution was not divinely inspired. No special providence was involved in her founding, nor has she discovered any unique principle of human governance. … And while she is indeed plunging into a ravine, every realistic way to save her starts with centralizing all sovereign power in a single person – or at most a small team. This historically normal political structure is the appropriate way to terminate a failed experiment in political science, which appeared to work only because it started off with an amazing population in an empty continent on the threshold of an industrial revolution. …

The conservatives, when they feel the bumps under their seats and realize the train is not on rails, feel each bump as a problem to be solved. DEI is a problem to be solved. Mass migration is a problem to be solved. The fentanyl epidemic is a problem to be solved.

Yet not only are the conservatives’ solutions wildly, fantastically disproportionate – by orders of magnitude – to these problems, they are not the real problems. They are only symptoms of the real problem – that our country is lost in history. There are no rails. There never were any.

But your quixotic, but energetically and even brilliantly conducted, fight against just one of these symptoms, in which even when your sword goes home and sinks to the hilt, you only demonstrate what a pinprick it is to this Brobdignagian monster, serves a different purpose. You are not defeating the enemy. You are only revealing it – showing everyone that the monster is real, and brave and capable men can fight it. Let us learn to fight it well – and let us learn to make it show its face. I complain, but I do not know of – for now – a better way.

Rufo: Let’s be real. You claim to have immense ambitions — although you don’t seem inclined to elaborate on them — but what are your practical accomplishments? My record is well-documented. If you permit me a moment of immodesty, my work has mobilized public opinion, launched a grassroots movement, inspired a presidential order, ousted the president of Harvard, recruited a cohort of billionaire defectors, pushed the DEI complex into contraction, and changed the law in every red state, some of which have restricted left-wing race and gender theories in schools, abolished DEI in universities, and instituted universal school choice statewide. This work is admittedly tentative and incomplete, but it has initiated a real shift in culture, law, and governance that might, with continued effort, provide a pathway for a “return to the beginnings of the republic.”

What about you? What is your practical politics and what have you done toward achieving it? If your ideas have thus far been unable to win and govern a local school board, why should we assume that they can govern a complex nation? …

Over the course of this dialogue, I have asked you a series of basic questions, which you have systematically ignored. Your contribution has consisted instead, for the most part, of childish insults, bouts of paranoia, heavy italics, pointless digressions, competitive bibliography, and allusions to cartoons. It’s disturbing to realize that this is how your mind works now. I don’t think it was always this way, but here we are.

What seems characteristic about your current position is that your rhetoric is constantly working to prove that you’re smarter than anyone else, but when one tries to locate what it is that you actually think, he cannot help but discover that there really isn’t much substance there. Ultimately, you are a sophist: your writing might create a small magnetic field, but underneath it, there is nothing.

You write, astonishingly, that your “picture of winning is very clear.” But what you have actually written here amounts to vague, half-baked gestures about “absolute power.” When asked to define it, you offer us Paw Patrol. … Lifting metaphors from action films and fantasy novels is not a substitute for the practical work of governance, or even the practical work of serious thought.

You’re too clever not to know this, but you are also too arrogant to fully accept it.

A hymn for (Burkean) conservatives everywhere

Well, after that unpleasantness, we need to rinse our minds out with something with a bit of presence, a bit of heft. Something we can admire and honour. It’s a hymn I must have heard quite a few times — and probably sung at school — without taking notice of it until I went to the funeral of Manning Clark whom I knew quite well (having lived in his garage for a period) and been a recipient of his extraordinary generosity — though his wonderful wife Dymphna did the actual work ;)

Anyway, it was a hymn that Manning sought to mainline in his six volumes of Australian history. It also struck me that it embodies conservatism at its best — even if I can never quite get past the ‘encircling gloom’ business — they really should have switched out of coal a little sooner.

Will progressive elites ever help the poor?

As I read this, I decided I wasn’t going to extract it for you because I didn’t think it was good enough. But when I got to the last few paragraphs, I thought it put its case well even though I’m neither endorsing it nor disagreeing with it. Just letting it mull. It’s a relatively critical review of Freddie Deboer’s book, How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement.

The book suffers for the attempt, as deBoer resists the implications and logical conclusions of his own argument. Each page is threaded through with equivocation, as critique gives way to apologetics. Every criticism comes bound up with its own equal-and-opposite ‘on the other hand…’ Progressives are out of touch with the public and the “marginalized” communities they claim to represent, but that’s OK because “political movements have always been driven by a vanguard” and activists are meant to be agents of change. Dividing people into identity groups is “inimical to solidarity,” but also progressive movements must cater to the particular needs of various minorities. Calls to defund the police and defences of rioting and political violence are counterproductive and misguided, but the protests of 2020 were nonetheless righteous and had “legitimate grievances and moral demands.” A whole chapter details the many ways in which the non-profit sector saps human and fiscal resources that might be better allocated to civil service programmes, unions, and grassroots organizations, only for deBoer to conclude that non-profits are nonetheless “essential to the basic operations of left-wing activism.” He bends over backward in service of the most charitable possible reading of the very elites who supposedly derailed the social justice movement. Affluent progressives and liberals may undermine movements for economic justice out of a self-serving obsession with frivolous symbolic politics but, deBoer somehow contends, they mean well. Though whole chapters are devoted to detailing the perverse social and economic interests that put affluent liberals in the professional-managerial class at odds with the poor and the working class, deBoer somehow decides that the former’s obsession with identity and symbolic politics is “only because of the strange and unfortunate cultural moment they find themselves in.” Pity the liberal, for he knows not what he does!

DeBoer won’t give up on progressives, no matter their faults. Republicans are dismissed as reactionaries and low-information voters. He regrets that the face of the progressive left is “some college-educated elite in a tony neighborhood in an expensive city,” rather than the common man, but insists that “you go to war with the coalition you have, not the coalition you wish you had.” His mission is thus, in his own words, to turn liberals into leftists. Of course, the trend has been in the reverse. Liberal identity politics have come to define the left, and class-focused movements, such as Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders presidential campaigns, are invariably co-opted by and subsumed into the broader identitarian progressive movement. In an omnibus review of recently released “anti-woke” books by authors spanning the political spectrum, including deBoer’s, Geoff Shullenberger notes that “It isn’t clear the class-first cohort has any response to these failures other than to keep trying.”

In the war for the soul of progressivism, the identity-obsessed liberals are clearly winning. There is no reason to expect this to change given the nature of the coalition. Progressive elites, as deBoer shows, are holding the reins. They won’t be persuaded into an economic populism that runs counter to their own material interests. A progressivism that works for the people, not the elite, is going to have to leave the latter behind.

The enemy within: live on a screen near you

Gripping podcast on the Newcastle Anglican Church

PROLOGUE

Hell on Earth

Washington, D.C.,

Possibly Sometime in the Near FutureA1-megaton thermonuclear weapon detonation begins with a flash of light and heat so tremendous it is impossible for the human mind to comprehend. One hundred and eighty million degrees Fahrenheit is four or five times hotter than the temperature that occurs at the center of the Earth’s sun.

In the first fraction of a millisecond after this thermonuclear bomb strikes the Pentagon outside Washington, D.C., there is light. Soft X-ray light with a very short wavelength. The light superheats the surrounding air to millions of degrees, creating a massive fireball that expands at millions of miles per hour. Within a few seconds, this fireball increases to a diameter of a little more than a mile (5,700 feet across), its light and heat so intense that concrete surfaces explode, metal objects melt or evaporate, stone shatters, humans instantaneously convert into combusting carbon.

The five-story, five-sided structure of the Pentagon and everything inside its 6.5 million square feet of office space explodes into superheated dust from the initial flash of light and heat, all the walls shattering with the near-simultaneous arrival of the shock wave, all 27,000 employees perishing instantly.

Not a single thing in the fireball remains.

Nothing.

Ground zero is zeroed.

Traveling at the speed of light, the radiating heat from the fireball ignites everything flammable within its line of sight several miles out in every direction. Curtains, paper, books, wood fences, people’s clothing, dry leaves explode into flames and become kindling for a great firestorm that begins to consume a 100-or-more-square-mile area that, prior to this flash of light, was the beating heart of American governance and home to some 6 million people.

Several hundred feet northwest of the Pentagon, all 639 acres of Arlington National Cemetery—including the 400,000 sets of bones and gravestones honoring the war dead, the 3,800 African American freedpeople buried in section 27, the living visitors paying respects on this early spring afternoon, the groundskeepers mowing the lawns, the arborists tending to the trees, the tour guides touring, the white-gloved members of the Old Guard keeping watch over the Tomb of the Unknowns—are instantly transformed into combusting and charred human figurines. Into black organic-matter powder that is soot. Those incinerated are spared the unprecedented horror that begins to be inflicted on the 1 to 2 million more gravely injured people not yet dead in this first Bolt out of the Blue nuclear strike.

Across the Potomac River one mile to the northeast, the marble walls and columns of the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials superheat, split, burst apart, and disintegrate. The steel and stone bridges and highways connecting these historic monuments to the surrounding environs heave and collapse. To the south, across Interstate 395, the bright and spacious glass-walled Fashion Centre at Pentagon City, with its abundance of stores filled with high-end clothing brands and household goods, and the surrounding restaurants and offices, along with the adjacent Ritz-Carlton, Pentagon City hotel—they are all obliterated. Ceiling joists, two-by-fours, escalators, chandeliers, rugs, furniture, mannequins, dogs, squirrels, people burst into flames and burn. It is the end of March, 3:36 p.m. local time.

It has been three seconds since the initial blast. There is a baseball game going on two and a half miles due west at Nationals Park. The clothes on a majority of the 35,000 people watching the game catch on fire. Those who don’t quickly burn to death suffer intense third-degree burns. Their bodies get stripped of the outer layer of skin, exposing bloody dermis underneath.

Third-degree burns require immediate specialized care and often limb amputation to prevent death. Here inside Nationals Park there might be a few thousand people who somehow survive initially. They were inside buying food, or using the bathrooms indoors—people who now desperately need a bed at a burn treatment center. But there are only ten specialized burn beds in the entire Washington metropolitan area, at the MedStar Washington Hospital’s Burn Center in central D.C. And because this facility is about five miles northeast of the Pentagon, it no longer functions, if it even exists. At the Johns Hopkins Burn Center, forty-five miles northeast, in Baltimore, there are less than twenty specialized burn beds, but they all are about to become filled. In total there are only around 2,000 specialized burn unit beds in all fifty states at any given time.

Within seconds, thermal radiation from this 1-megaton nuclear bomb attack on the Pentagon has deeply burned the skin on roughly 1 million more people, 90 percent of whom will die. Defense scientists and academics alike have spent decades doing this math. Most won’t make it more than a few steps from where they happen to be standing when the bomb detonates. They become what civil defense experts referred to in the 1950s, when these gruesome calculations first came to be, as “Dead When Found.”

Humans created the nuclear weapon in the twentieth century to save the world from evil, and now, in the twenty-first century, the nuclear weapon is about to destroy the world. To burn it all down.

The science behind the bomb is profound. Embedded in the thermonuclear flash of light are two pulses of thermal radiation. The first pulse lasts a fraction of a second, after which comes the second pulse, which lasts several seconds and causes human skin to ignite and burn. The light pulses are silent; light has no sound. What follows is a thunderous roar that is blast. The intense heat generated by this nuclear explosion creates a high-pressure wave that moves out from its center point like a tsunami, a giant wall of highly compressed air traveling faster than the speed of sound. It mows people down, hurls others into the air, bursts lungs and eardrums, sucks bodies up and spits them out. “In general, large buildings are destroyed by the change in air pressure, while people and objects such as trees and utility poles are destroyed by the wind,” notes an archivist who compiles these appalling statistics for the Atomic Archive.

As the nuclear fireball grows, this shock front delivers catastrophic destruction, pushing out like a bulldozer and moving three miles farther ahead. The air behind the blast wave accelerates, creating several-hundred-mile-per-hour winds, extraordinary speeds that are difficult to fathom. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy, which did $70 billion in damage and killed some 147 people, had maximum sustained winds of roughly 80 miles per hour. The highest wind speed ever recorded on Earth was 253 miles per hour, at a remote weather station in Australia. This nuclear blast wave in Washington, D.C., destroys all structures in its immediate path, instantly changing the physical shapes of engineered structures including office buildings, apartment complexes, monuments, museums, parking structures—they disintegrate and become dust. That which is not crushed by blast is torn apart by whipping wind. Buildings collapse, bridges fall, cranes topple over. Objects as small as computers and cement blocks, and as large as 18-wheeler trucks and double-decker tour buses, become airborne like tennis balls.

The nuclear fireball that has been consuming everything in the initial 1.1-mile radius now rises up like a hot-air balloon. Up from the earth it floats, at a rate of 250 to 350 feet per second. Thirty-five seconds pass. The formation of the iconic mushroom cloud begins, its massive cap and stem, made up of incinerated people and civilization’s debris, transmutes from a red, to a brown, to an orange hue. Next comes the deadly reverse suction effect, with objects—cars, people, light poles, street signs, parking meters, steel carrier beams—getting sucked back into the center of the burning inferno and consumed by flame.

Sixty seconds pass.

The mushroom cap and stem, now grayish white, rises up five then ten miles from ground zero. The cap grows too, stretching out ten, twenty, thirty miles across, billowing and blowing farther out. Eventually it reaches beyond the troposphere, higher than commercial flights go, and the region where most of the Earth’s weather phenomena occurs. Radioactive particles spew across everything below as fallout raining back down on the Earth and its people. A nuclear bomb produces “a witch’s brew of radioactive products which are also entrained in the cloud,” the astrophysicist Carl Sagan warned decades ago.

More than a million people are dead or dying and less than two minutes have passed since detonation. Now the inferno begins. This is different from the initial fireball; it is a mega-fire beyond measure. Gas lines explode one after the next, acting like giant blowtorches or flamethrowers, spewing steady streams of fire. Tanks containing flammable materials burst open. Chemical factories explode. Pilot lights on water heaters and furnaces act like torch lighters, setting anything not already burning alight. Collapsed buildings become like giant ovens. People, everywhere, burn alive.

Open gaps in floors and roofs behave like chimneys. Carbon dioxide from the firestorms sinks down and settles into the metro’s subway tunnels, asphyxiating riders in their seats. People seeking shelter in basements and other spaces belowground vomit, convulse, become comatose, and die. Anyone aboveground who is looking directly at the blast—in some cases as far as thirteen miles away—becomes blinded.

Seven and a half miles out from ground zero, in a 15-mile diameter ring around the Pentagon (the 5 psi zone), cars and buses crash into one another. Asphalt streets turn to liquid from the intense heat, trapping survivors as if caught in molten lava or quicksand. Hurricane-force winds fuel hundreds of fires into thousands of fires, into millions of them. Ten miles out, hot burning ash and flaming wind-borne debris ignite new fires, and one after another they continue to conflate. All of Washington, D.C., becomes one complex firestorm. A mega-inferno. Soon to become a mesocyclone of fire. Eight, maybe nine minutes pass.

Ten and twelve miles out from ground zero (in the 1 psi zone), survivors shuffle in shock like the almost dead. Unsure of what just happened, desperate to escape. Tens of thousands of people here have ruptured lungs. Crows, sparrows, and pigeons flying overhead catch on fire and drop from the sky as if it is raining birds. There is no electricity. No phone service. No 911.

The localized electromagnetic pulse of the bomb obliterates all radio, internet, and TV. Cars with electric ignition systems in a several-mile ring outside the blast zone cannot restart. Water stations can’t pump water. Saturated with lethal levels of radiation, the entire area is a no-go zone for first responders. Not for days will the rare survivors realize help was never on the way.

Those who somehow manage to escape death by the initial blast, shock wave, and firestorm suddenly realize an insidious truth about nuclear war. That they are entirely on their own. Former FEMA director Craig Fugate tells us their only hope for survival is to figure out how to “self-survive.” That here begins a “fight for food, water, Pedialyte . . .”

How, and why, do U.S. defense scientists know such hideous things, and with exacting precision? How does the U.S. government know so many nuclear effects–related facts, while the general public remains blind? The answer is as grotesque as the questions themselves because, for all these years, since the end of World War II, the U.S. government has been preparing for, and rehearsing plans for, a General Nuclear War. A nuclear World War III that is guaranteed to leave, at minimum, 2 billion dead.

To know this answer more specifically, we go back in time, more than sixty years. To December 1960. To U.S. Strategic Air Command, and a secret meeting that took place there.

Lovely

Heaviosity half hour

Montaigne on interpretation

From “On Experience”

When King Ferdinand sent colonies of immigrants to the Indies he made the wise stipulation that no one should be included who had studied jurisprudence, lest lawsuits should pullulate in the New World – law being of its nature a branch of learning subject to faction and altercation: he judged with Plato that to furnish a country with lawyers and doctors is a bad action.11

Why is it that our tongue, so simple for other purposes, becomes obscure and unintelligible in wills and contracts? Why is it that a man who expresses himself with clarity in anything else that he says or writes cannot find any means of making declarations in such matters which do not sink into contradictions and obscurity? Is it not that the ‘princes’ of that art,12 striving with a peculiar application to select traditional terms and to use technical language, have so weighed every syllable and perused so minutely every species of conjunction that they end up entangled and bogged down in an infinitude of grammatical functions and tiny sub-clauses which defy all rule and order and any definite interpretation? [C] ‘Confusum est quidquid usque in pulverem sectum est.’ [Cut anything into tiny pieces and it all becomes a mass of confusion.]13

[B] Have you ever seen children making assays at arranging a pile of quicksilver into a set number of segments? The more they press it and knead it and try to make it do what they want the more they exasperate the taste for liberty in that noble metal: it resists their art and proceeds to scatter and break down into innumerable tiny parts. It is just the same here: for by subdividing those subtle statements lawyers teach people to increase matters of doubt; they start us off extending and varying our difficulties, stretching them out and spreading them about. By sowing doubts and then pruning them back they make the world produce abundant crops of uncertainties and quarrels, [C] just as the soil is made more fertile when it is broken up and deeply dug: ‘difficultatem facit doctrina’ [it is learning which creates the difficulty].14

[B] We have doubts on reading Ulpian: our doubts are increased by Bartolo and Baldus.15 The traces of that countless diversity of opinion should have been obliterated, not used as ornaments or stuffed into the heads of posterity. All I can say is that you can feel from experience that so many interpretations dissipate the truth and break it up. Aristotle wrote to be understood: if he could not manage it, still less will a less able man (or a third party) manage to do better than Aristotle, who was treating his own concepts. By steeping our material we macerate it and stretch it. Out of one subject we make a thousand and sink into Epicurus’ infinitude of atoms by proliferation and subdivision. Never did two men ever judge identically about anything, and it is impossible to find two opinions which are exactly alike, not only in different men but in the same men at different times. I normally find matter for doubt in what the gloss has not condescended to touch upon. Like certain horses I know which miss their footing on a level path, I stumble more easily on the flat.

Can anyone deny that glosses increase doubts and ignorance, when there can be found no book which men toil over in either divinity or the humanities whose difficulties have been exhausted by exegesis? The hundredth commentator dispatches it to his successor prickling with more difficulties than the first commentator of all had ever found in it. Do we ever agree among ourselves that ‘this book already has enough glosses: from now on there is no more to be said on it?’ That can be best seen from legal quibbling. We give force of law to an infinite number of legal authorities, an infinite number of decisions and just as many interpretations. Yet do we ever find an end to our need to interpret? Can we see any progress or advance towards serenity? Do we need fewer lawyers and judges than when that lump of legality was in its babyhood?

On the contrary we obscure and bury the meaning: we can no longer discern it except by courtesy of those many closures and palisades. Men fail to recognize the natural sickness of their mind which does nothing but range and ferret about, ceaselessly twisting and contriving and, like our silkworms, becoming entangled in its own works: ‘Mus in pice.’ [A mouse stuck in pitch.]16 It thinks it can make out in the distance some appearance of light, of conceptual truth: but, while it is charging towards it, so many difficulties, so many obstacles and fresh diversions strew its path that they make it dizzy and it loses its way. The mind is not all that different from those dogs in Aesop which, descrying what appeared to be a corpse floating on the sea yet being unable to get at it, set about lapping up the water so as to dry out a path to it, [C] and suffocated themselves.17 And that coincides with what was said about the writings of Heraclitus by Crates: they required a reader to be a good swimmer, so that the weight of his doctrine should not pull him under nor its depth drown him.18

[B] It is only our individual weakness which makes us satisfied with what has been discovered by others or by ourselves in this hunt for knowledge: an abler man will not be satisfied with it. There is always room for a successor – [C] yes, even for ourselves – [B] and a different way to proceed. There is no end to our inquiries: our end is in the next world.19

[C] When the mind is satisfied, that is a sign of diminished faculties or weariness. No powerful mind stops within itself: it is always stretching out and exceeding its capacities. It makes sorties which go beyond what it can achieve: it is only half-alive if it is not advancing, pressing forward, getting driven into a corner and coming to blows; [B] its inquiries are shapeless and without limits; its nourishment consists in [C] amazement, the hunt and [B] uncertainty,20 as Apollo made clear enough to us by his speaking (as always) ambiguously, obscurely and obliquely, not glutting us but keeping us wondering and occupied.21 It is an irregular activity, never-ending and without pattern or target. Its discoveries excite each other, follow after each other and between them produce more.

Ainsi voit l’on, en un ruisseau coulant,

Sans fin l’une eau apres l’autre roulant,

Et tout de rang, d’un eternel conduict,

L’une suit l’autre, et l’une l’autre fuyt.

Par cette-cy celle-là est poussée,

Et cette-cy par l’autre est devancée:

Tousjours l’eau va dans l’eau, et tousjours est-ce

Mesme ruisseau, et toujours eau diverse.[Thus do we see in a flowing stream water rolling endlessly on water, ripple upon ripple, as in its unchanging bed water flees and water pursues, the first water driven by what follows and drawn on by what went before, water eternally driving into water – even the same stream with its waters ever-changing.]22

It is more of a business to interpret the interpretations than to interpret the texts, and there are more books on books than on any other subject: all we do is gloss each other. [C] All is a-swarm with commentaries: of authors there is a dearth. Is not learning to understand the learned the chief and most celebrated thing that we learn nowadays! Is that not the common goal, the ultimate goal, of all our studies?

Statistics: Post wisdom governance

I didn’t know that the word statistics came from something like ‘statecraft’. But it did.

[A]t the level of content, what must be known in order to be able to govern? I think we see an important phenomenon here, an essential transformation. In the images, the representation, and the art of government as it was defined up to the start of the seventeenth century, the sovereign essentially had to be wise and prudent. What did it mean to be wise? Being wise meant knowing the laws: knowing the positive laws of the country, the natural laws imposed on all men, and, of course, the commandments of God himself. Being wise meant knowing the historical examples, the models of virtue, and making them rules of behavior. On the other hand, the sovereign had to be prudent, that is to say, to know in what measure, when, and in what circumstances it was actually necessary to apply this wisdom. When, for example, should the laws of justice be rigorously applied, and when, rather, should the principles of equity prevail over the formal rules of justice? Wisdom and prudence, that is to say, in the end an ability to handle laws.

At the start of the seventeenth century I think we see the appearance of a completely different description of the knowledge required by someone who governs. What the sovereign or someone who governs, the sovereign inasmuch as he governs, must know is not just the laws, and it is not even primarily or fundamentally the laws (although one always refers to them, of course, and it is necessary to know them). What I think is new, crucial, and determinant is that the sovereign must know those elements that constitute the state … That is to say, someone who governs must know the elements that enable the state to be preserved in its strength, or in the necessary development of its strength, so that it is not dominated by others or loses its existence by losing its strength or relative strength. That is to say, the sovereign’s necessary knowledge (savoir) will be a knowledge (connaissance) of things rather than knowledge of the law, and this knowledge of things that comprise the very reality of the state is precisely what at the time was called “statistics.” Etymologically, statistics is knowledge of the state, of the forces and resources that characterize the state at a given moment. For example, knowledge of the population, the measure of its quantity, mortality, natality; reckoning of the different categories of individuals in a state and of their wealth; assessment of the potential wealth available to the state, mines and forests, etcetera; assessment of the wealth in circulation, of the balance of trade, and measure of the effects of taxes and duties, all this data, and more besides, now constitute the essential content of the sovereign’s knowledge. So, it is no longer the corpus of laws or skill in applying them when necessary, but a set of technical knowledge that describes the reality of the state itself.

Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, and Population: Lectures at the College du France, 1977-1978. HT: Timothy Taylor.

Thinking politically or thinking ideologically?

The distinguished case of Raymond Aron

Raymond Aron: thinking politically is thinking without Archimedes’ skyhook

Burnham spoke of thinking ‘scientifically’ about politics. When he said that nine tenths of political thinking was basically wish fulfilment, another way of putting what he was saying is that abstract principles are all very well, but like values in our lives they’re traded off against each other. So they’re pretty unspecified except in concrete situations.

For me it’s not about thinking like a politician, but rather thinking without Archimedes Skyhook. That is, if we want to think about politics we need to think about concrete situations — not necessarily concrete situations in party politics, but circumstances that focus our mind on actual choices rather than nice ways we’d like the world to be. Nothing like focusing on some person’s need to choose what to do to shake us out of our daydreaming and force us to answer the Spice Girl’s question “Tell me what you want, what you really, really want.

From Daniel J Mahoney’s introduction to Raymond Aron’s Thinking Politically which is a popular anthology of Aron’s spoken words late in his life.

Friedrich Nietzsche prophesied with remarkable accuracy that the twentieth century would be marked by great wars fought in the name of philosophic concepts. What Nietzsche could not have anticipated was that the most trustworthy observer and commentator on the ideological drama of the twentieth century would be a French Jewish philosopher turned political scientist and historian—a man who would try to understand the forces challenging liberal, bourgeois civilization while using his immense critical powers to defend and sustain a political and social order that was judged to be antiquated, if not contemptible, by all the fashionable currents on the Left and Right.

Raymond Aron (1905–1983) was a philosopher, scholar, and a journalist, the author of important works on the philosophy of history, the nature of modern society, international relations, and political and sociological thought as well as a chronicler of what he called “history-in-the-making” for newspapers and magazines such as Le Figaro and L’Express and journals such as La France Libre, Preuves, Encounter, Contrepoint, and Commentaire. He was an applied “philosopher of history” who wished to do justice to the real role that individual initiative, political choice, and living ideas played in dialectically shaping the destiny of the century. In short, he respected the dramatic elements of human history. His philosophy of history, diffused throughout and undergirding his political and journalistic work, aimed to avoid the twin dangers of historical determinism and vitalistic voluntarism, associated in this century most closely with Marxism and existentialism.

Yet his early philosophic work was not unmarked by existentialism. In fact, in what might be seen retrospectively as an overreaction to the scientistic and positivistic tenor of French intellectual life in the interwar period, the young Aron proclaimed the open-ended plurality of interpretations of human works and events and the fundamentally free or undetermined character of human choice. Later he modified both the tone and substance of his early “existentialism” by emphasizing the enduring realities of human and social nature without losing sight of their often tragic complexity. But Aron’s greatness ultimately lies in his dual choice for a conservative-minded liberalism and a genuinely political perspective. He rejected both the secular religions of National Socialism and Marxism and the propensity of intellectuals to commit themselves to grand political adventures without paying sufficient attention to such inescapable constraints and givens of the human world as the structure of social life, the inheritance of the past, and, above all, the concrete choices facing citizens and statesman.This propensity is still evident among many of the well-known schools of contemporary political thought, which in advancing theoretical models detached from any reflection on the politically real, render themselves at best irrelevant, at worst, destructive. Raymond Aron cured himself of a youthful political naivete by immersing himself in the study of modern political economy, the nature of diplomatic-strategic conduct and the character of modern warfare. His mature work was subsequently characterized by an ongoing critical evaluation of the ideological pretenses and actual consequences of the principal anti-liberal doctrines of the twentieth century as well as a Thucydidean attentiveness to the thought and action of participants in political life.

Aron called himself a” committed observer,” by which he meant that his political engagement flowed from attentive historical observation and political reflection and not from a literary, abstract, or ideological image of what a desirable society ought to look like. His contemporaries—most notably Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Jean-Paul Sartre—dreamed of the “universalizable society” founded upon “historical reason.” Incredibly, they identified that society, for much too long, with the totalitarian Soviet Union. Aron, in contrast, while not rejecting “critical reason,” believed that it must become truly historical by being fully concrete in its operations.

There are perhaps more scholarly introductions to Aron’s political reflection than Thinking Politically, but none that is more accessible nor more revealing of his synthesis of careful, empirical observation and principled, humane political judgment.1

Thinking Politically consists of three principal parts. The first is the republication of The Committed Observer, a series of interviews conducted with Raymond Aron by two vaguely leftist professors and journalists, Jean-Louis Missika and Dominique Wolton. These interviews appeared on French television in 1980 and were published in revised book form in 1981. Both the interviews and the book were a huge success with the French public and prefigured the welcoming reception of his Memoirs before and after Aron’s death in November of 1983. The Committed Observer is important on several levels: it is the clearest introduction to Aron’s life and thought; it provides an overview and evaluation of the major events, ideas, ideologies, thinkers, and actors of the twentieth century; and it is above all a vindication of Aron’s model of political reflection and of his sober yet intellectually rich conservative liberalism. In reviewing his own work and the principal events of the century, Aron reveals a different and, one is tempted to say, more radical example of political engagement. Throughout this work Aron shows, in speech and deed, that true engagement is possible only when one is willing to think politically, that is to look at political choice by embracing the perspective of the engaged and responsible citizen and statesman. The key exchange in The Committed Observer is so fundamental that it is necessary to highlight it by quoting at length:

Dominique Wolton. — Also, you often say that the intellectuals of the Left refuse to think politically. You mean that they refuse to build and take action?

Raymond Aron. — It means two things. First, they prefer ideology, that is, a rather literary image of a desirable society, rather than to study the functioning of a given economy, of a liberal economy, of a parliamentary system, and so forth.

And then there is a second element, perhaps more basic: the refusal to answer the question someone once asked me: “If you were in the minister’s position, what would you do?” When I returned from Germany in 1932—I was very young—I had a conversation with the secretary of state for foreign affairs, Paganon. “Tell me about your experiences,” he said. I made a very Ecole Normale kind of presentation, apparently brilliant—at the time, my presentations were brilliant. “All that is very interesting,” he said after about fifteen minutes, “but if you were in my place, what would you do?” Well, I was much less brilliant in the answer to that question.

The same story happened to me, but the other way around, with Albert Ollivier. He had written a splendid article in Combat against a minister. “In his place,” I asked, “what would you do?” He replied, “That’s not my job. It’s up to the minister to find the solution; my responsibility is to criticize.” I rejoined that I did not have exactly the same concept of my role as a journalist. And I must say that, thanks to Mr. Paganon, I have throughout my journalistic career always asked myself, “What would I do if I were in the place of the ministers?”

The interviews with Missika and Wolton bring Aron’s political perspective vividly to life. They also illustrate Aron’s classicism: the myriad ways in which his thought was informed by an ongoing dialogue with the great men of the past, including Aristotle, Machiavelli, Tocqueville, Montesquieu, Marx, and Weber. Aron believed such dialogue necessary for the health of culture, for a full understanding of our world, and for the maintenance of our capacity to admire what is genuinely admirable. But above all, The Committed Observer displays the nonpartisan character of Aron’s political commitment. Aron fulfilled the chief civic function of the political philosopher as articulated by Aristotle in Book III of The Politics. The political philosopher aims to be the good citizen par excellence by moderating the already overheated and partial commitments of the various partisan camps agonistically contending in the life of the political regime. The political philosopher seeks to prevent the outbreak of civil war by educating the public toward the common good, not through preaching but by setting an imitable and humanizing example of good citizenship. Even in those situations where Aron acted most firmly and unequivocally, such as after the catastrophe of June 1940 or during the revolutionary “psychodrama” of 1968, he was always guided by a desire to avoid any unnecessary ex-acerbations of civic tensions or divisions. Whether temporarily on the Left or Right in the ideological debates of the day, he always remained, in thought and feeling, a nonpartisan in the most fundamental and radical sense.