What an epic 18th-century scientific row teaches us today

A wonderful story. No prizes for guessing whose side I’m on. I’m shocked, shocked I tell you that “a brilliant but ruthless dogmatist” should have an outsized influence on the academy.

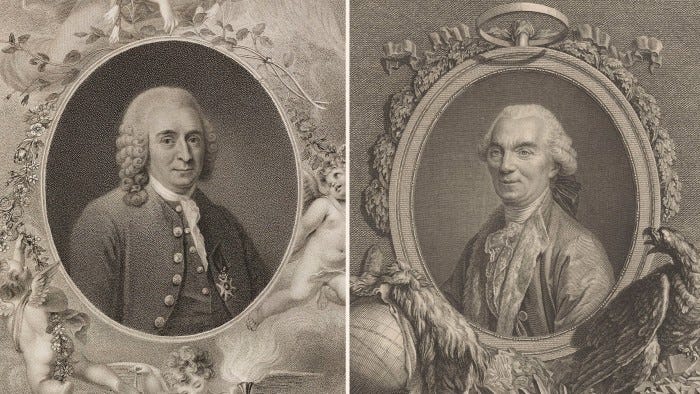

The aristocratic French polymath Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon chose a good year to die: 1788. Reflecting his status as a star of the Enlightenment and author of 35 popular volumes on natural history, Buffon’s funeral carriage drawn by 14 horses was watched by an estimated 20,000 mourners as it processed through Paris. A grateful Louis XVI had earlier erected a statue of a heroic Buffon in the Jardin du Roi, over which the naturalist had masterfully presided. “All nature bows to his genius,” the inscription read.

The next year, the French Revolution erupted. As a symbol of the ancien regime, Buffon was denounced as an enemy of progress, his estates in Burgundy seized, and his son, known as the Buffonet, guillotined. In further insult to his memory, zealous revolutionaries marched through the king’s gardens (nowadays known as the Jardin des Plantes) with a bust of Buffon’s great rival, Carl Linnaeus. They hailed the Swedish scientific revolutionary as a true man of the people.

The intense intellectual rivalry between Buffon and Linnaeus, which still resonates today, is fascinatingly told by the author Jason Roberts in his book Every Living Thing, my holiday reading while staying near Buffon’s birthplace in Burgundy. Natural history, like all history, might be written by the victors, as Roberts argues. And for a long time, Linnaeus’s highly influential but flawed views held sway. But the book makes a sympathetic case for the further rehabilitation of the much-maligned Buffon.

The two men were, as Roberts writes, exact contemporaries and polar opposites. While Linnaeus obsessed about classifying all biological species into neat categories with fixed attributes and Latin names (Homo sapiens, for example), Buffon emphasised the vast diversity and constantly changing nature of every living thing.

In Roberts’s telling, Linnaeus emerges as a brilliant but ruthless dogmatist who ignored inconvenient facts that did not fit his theories and gave birth to racial pseudoscience. But it was Buffon’s painstaking investigations and acceptance of complexity that helped inspire the evolutionary theories of Charles Darwin, who later acknowledged that the French- man’s ideas were “laughably like mine”.

In two aspects, at least, this 18th-century scientific clash rhymes with our times. The first is to show how intellectual knowledge can often be a source of financial gain. The discovery of crops and commodities in other parts of the world and the development of new methods of cultivation had a huge impact on the economy in that era. “All that is useful to man ori- ginates from these natural objects,” Linnaeus wrote. “In one word, it is the foundation of every industry.”

Great wealth was generated from trade in sugar, potatoes, coffee, tea and cochineal while Linnaeus himself explored ways of cultivating pineapples, strawberries and freshwater pearls.

“In many ways, the discipline of natural history in the 18th century was roughly analogous to technology today: a means of disrupting old markets, creating new ones, and generating fortunes in the process,” Roberts writes. As a former software engineer at Apple and a West Coast resident, Roberts knows the tech industry.

Then, as now, the addition of fresh inputs into the economy — whether natural commodit- ies back then or digital data today — can lead to astonishing progress, benefiting millions. But it can also lead to exploitation. As Roberts tells me in a telephone interview, it was the scaling up of the sugar industry in the West Indies that led to the slave trade. “Sometimes we think we are inventing the future when we are retrofitting the past,” he says.

The second resonance with today is the danger of believing we know more than we do. Roberts compares Buffon’s state of “curious unknowing” to the concept of “negative capability” described by the English poet John Keats. In a letter written in 1817, Keats argued that we should resist the temptation to explain away things we do not properly understand and accept “uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

Armed today with instant access to information and smart machines, the temptation is to ascribe a rational order to everything, as Linnaeus did. But scientific progress depends on a humble acceptance of relative ignorance and a relentless study of the fabric of reality.

The spooky nature of quantum mechanics would have blown Linnaeus’s mind. If Buffon still teaches us anything, it is to study the peculiarity of things as they are, not as we might wish them to be.

A hymn

Here’s a hymn to coincide with this newsletter switching from being released on the Jewish to the Christian sabbath (Comms Division suggested this to tip-toe around some controversy that’s apparently bubbled up in the territory formerly known as the Holy Land). The hymn was also written for children which also chimes with our changing priorities for market penetration.

Be that as it may I was struck not just by the beauty of this hymn — in its old fashioned way — but also with how apposite its key words are for our own time.

Anger, greed and truth.

I guess the fundamental things apply as time goes by.

When a knight won his spurs, in the stories of old,

He was gentle and brave, he was gallant and bold

With a shield on his arm and a lance in his hand,

For God and for valour he rode through the land.No charger have I, and no sword by my side,

Yet still to adventure and battle I ride,

Though back into storyland giants have fled,

And the knights are no more and the dragons are dead.Let faith be my shield and let joy be my steed

'Gainst the dragons of anger, the ogres of greed;

And let me set free with the sword of my youth,

From the castle of darkness, the power of the truth.

And click on the button below should you wish to see the fairytale, the allegory, the metaphor around the hymn by the historian whose substack I took it from.

Self-righteousness and expediency

And lo, political commentary as race-calling came upon the land and, over the course of a generation or two everyone was on the Insiders couch in their own head opining about whether Albo or Dutton had had the better week. And the Lord looked upon his creation and wondered where it had all gone wrong.

Be that as it may, here’s a column on Peter Dutton which, rather than foregrounding whether it’s right or wrong (though it’s clear what he thinks), asks whether Peter Dutton’s soft racism is really working for him politically. It concludes that, unless you’re in government where you get much more ability to shape the agenda, it likely isn’t. In this it might have the kind of influence that economists had on the debate about slavery and colonisation as domination. It wasn’t just wrong. It wasn’t even in the slaveholding society’s interests.

Or as Tallyrand is supposed to have said of Napoleon’s ordering the execution of a general “It was worse than a crime; it was a mistake.” Here’s fellow second generation Dunera Boy Peter Brent on why Peter Dutton’s dog whistling isn’t just a crime, but a mistake.

Peter Dutton has a nasty habit he just can’t break: attempting to stir public resentment towards — and let’s not mince words — dark-skinned immigrants, actual or potential. It’s his go-to comfort zone. African gangs; the Fraser government’s Lebanese intake; all those refugees who either take Australians’ jobs, he warns, or languish on the dole.

Casting further (and this one suggests he spends too much time in the far-right reaches of social media, where it’s a cause célèbre) he’s been down the rabbit hole where white South African farmers “need help from a civilised country like ours” and would be “the sorts of migrants that we want to bring into our country.” Julie Bishop had to clean up that mess.

This all happened when he was a government minister. Since becoming opposition leader in 2022 he’s made the threat of asylum seekers a regular component of his repertoire, regardless of any particular political logic. And the latest version, of course, is people fleeing Gaza, none of whom should be allowed into Australia.

This brand of politics goes down a treat in a section of the party room and the wider conservative movement, and Dutton might not have become Liberal leader without it. Scott Morrison also rode to the top employing inflammatory rhetoric in the immigration portfolio but, always a wilier individual, he shifted his presentation towards the centre once he got there. It’s worth noting that in both cases the path to the pinnacle was strictly an internal matter; there was little public desire for either man to become leader.

The inevitable, interminable “Dutton is racist!” “No, you’re out of touch!” back-and-forth misses the point. Most of us have elements of such prejudices lurking inside; if nothing else they’re the remnants of early socialisation. Human beings with a degree of self-awareness attempt to transcend harmful thought patterns. It’s part of the process of growing up.

Some politicians consciously try to capitalise on these sentiments and some consciously don’t, and Dutton resides firmly, more than any of his senior major-party contemporaries, in the former group. …

I have long been sceptical [that this is effective politics]. Of course, race-based messages have a visceral appeal for some people, and a subtle effect on many more. But like that other supposed Coalition trump card, opposition to action on climate change, it’s a two-edged sword. At some level voters know they’re being played. And they know it’s not dignified behaviour.

Ask John Howard. No, not the 2001 Tampa–“children overboard” version, but the 1988 one, whose proposal to limit Asian immigration was approved by 77 per cent in a Newspoll but didn’t improve his standing in the opinion polls, and indeed contributed to his removal as opposition leader the following year.

Five years later a rejigged Howard felt the need to half-heartedly apologise to the Asian community. It’s true that later again, in the second half of his prime ministership, he delighted in this politics of division, but you can get away with more as incumbent than aspirant. And if you’re in office for a long time — a roaring economy with historically low interest rates can do that for a government — everything you do comes to be seen as the secret to your success. Perceptions from that time pollute our politics to this day.…

The refugees from Gaza Dutton is talking about aren’t “illegal” anyway. But it’s really all about the vibe. … Dutton’s aping of Trump excites the crazies in the Coalition base, and as with climate change they’ve convinced themselves it’s great politics. But to voters looking for solutions to their cost-of-living problems it’s just off-topic. And it obviously doesn’t help Dutton in “teal” seats.

So bring on the analyses of Dutton’s political craftiness, his crude but effective manoeuvres. Prepare also for the puff pieces quoting family and neighbours attesting that Peter is misunderstood, he doesn’t really enjoy inflicting distress on the powerless. But he has no one but himself to blame for perceptions that he carries a lot of hate.

Peter’s neurotic vice damages not just the nation but also himself. Electorally, it’s a road to nowhere.

And speaking of the colour of people’s skin …

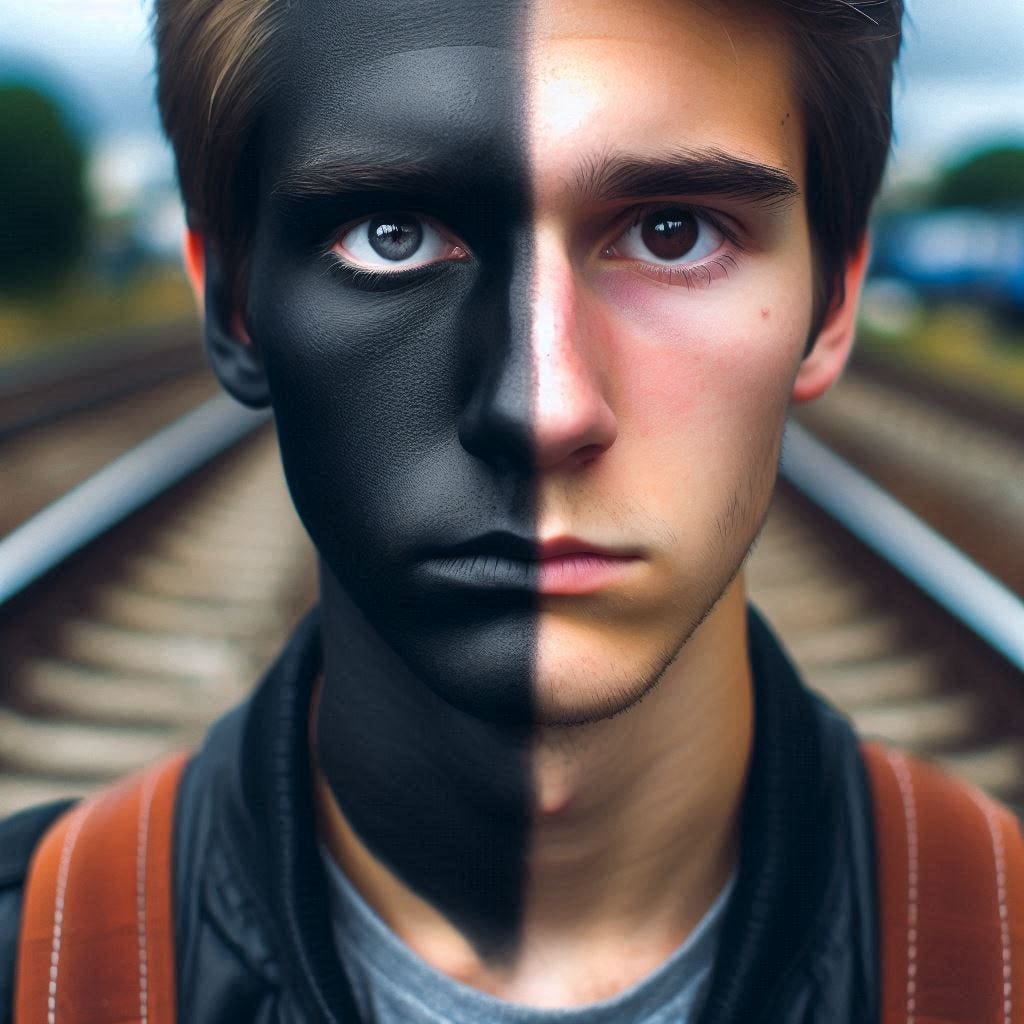

Are you binary or non-binary on race?

Fascinating differences — and, while race is especially sensitive in the US, the Anglosphere seems closer to the US than Latin America. I guess there wasn’t too much ‘whiteness’ malarky there.

I’m not sure which one’s harder, trying to explain Latin American racial attitudes to Anglos or Anglos’ racial attitudes to Latin Americans. Having split my life about evenly between Venezuela and North America, I’ve had to do both many times over. It seldom goes well, because race plays such a different role in each society. …

I always think back to one moment in 2001. George W. Bush had just chosen Colin Powell to serve as his Secretary of State, and the news wires were full of discussion about the then-historic event: the first Black Secretary of State. The journalists in the Caracas newsroom where I worked at the time found this simply bizarre.

“What the hell are they talking about, that guy’s not black,” my colleague Ligia said. “He’s barely café-con-leche,” she continued, using the Venezuelanism for variably-brown mixed race people. …

Venezuelan culture reduces race to skin color, but it doesn’t stop there. It then drains skin color of anything beyond a descriptive significance. As a result, Venezuelans see zero reason to hold back on commenting about it. Loudly.

Not for us the panicky gringo mania for walking on racial egg shells.

In North America, race is usually presented in either/or terms, whereas Venezuelans think of it much more as a spectrum, a chromatic scale that people fall along relative to each other. This is why racial labels are often context-dependent and relative: “catire” (roughly “blondie”) is simply what you call the fairest skinned person in a given setting, while “negro” is what you call whomever is darkest skinned. There’s even a popular saying in Venezuela that translates literally as “blond just means the least black in the village.”

If you find these racial attitudes confusing, trust me: Venezuelans find your racial attitudes ten times weirder. Try to explain to a Venezuelan that in many cases an American picking up the phone can tell instantly whether the person on the other end of the line is Black, and you’ll get an uncomprehending stare back.

“Wait, what? Does their skin somehow change their voice?! How?!”

To most Venezuelans, the claim itself seems racist. Where skin tone alone doesn’t map onto a clear group identity, the very idea of a racial accent seems ludicrous. No Venezuelan can tell the tone of the other person’s skin on the phone.

Of course, it’s not quite that simple: any Venezuelan can pick up the phone and instantly place the other party by class. And yes, due to the long overhang of colonial history, pale-skin and high class certainly do overlap.

But for the broad majority of working-class Venezuelans, people of all different skin tones share the same accents, with regional variations clearly noticeable but race entirely inaudible. Black working-class Venezuelans eat the same kinds of foods that white working-class Venezuelans eat, live in the same neighborhoods, go to the same churches, and certainly sound the same on the phone. …

Meditating on this over the years, I can’t help but feel that Latin Americans like Cavani have a much saner take on race than Americans. But then, we are only able to reduce race to skin tone because our racial history is vastly different.

Racial apartheid broke down in much of Latin America literally hundreds of years earlier than it did in the United States, as did the taboos against interracial marriage. Venezuela is an excellent example. Already in the 1790s, royal officials sent from Madrid to report on the state of the Captaincy General of Venezuela were alarmed by the scale of race-mixing in the colony, and the German philosopher-explorer Alexander von Humboldt, in his widely read letters from South America, estimated about half the population was mixed before the turn of the 19th century.

Over the next 200 years, Venezuelans continued merrily making babies across racial lines, creating a population that was overwhelmingly mestiza (mixed). By the 1960s, café con leche had become Venezuela’s official racial ideology: Venezuelans in general were presumed to be a little bit white, a little bit black and a little bit indigenous.

Freddie Deboer on the Black Lives Matter Grift

A brutal line from a brutal piece, about a nonprofit founder that took advantage of post-George Floyd fundraising largesse to enjoy a lavish lifestyle while producing nothing. There are two general ways that nonprofits fundraise forever while accomplishing nothing: first, by making their mission too vague to have any specific definition of success and thus to never fail; second, by making the mission too ambitious for anyone to ever believe that it can be accomplished. The supposed project of Raheem AI, to build a remarkably complicated AI-powered (lol) alternative to calling 911, falls in the second category. Unable to create anything like what he had said he would build, and living in the freewheeling period of do-gooding donors and corporations throwing money at racism, the founder did the sensible thing and took a lot of expensive vacations on the donor dime. That he also appears to have entirely fabricated his origin story is par for the course.

The sheer amount of graft and corruption that attended the vast orgy of donating associated with the George Floyd protest movement was perfectly predictable, but I think it’s still undersold as a reason for why that branch of politics has receded. Indeed, I think I’m guilty of underselling it myself. It’s worth saying that no political movement could have emerged from that scenario with clean hands; there was so much loose cash floating around all over the place, since institutions who fear the consequences of appearing insufficiently devoted to the cause always feel like they can spend their way out of such accusations. Pretty much every righteous political movement has had its own graft problem, all of them. Still, an incredible amount of giving meant an incredible amount of corruption. And as the months drifted by and it became clear that the American establishment was perfectly able to absorb what was happening, despite all the angst, and as the forces of culture war steadily pecked away at that short-lived feeling of unity, the inevitable discovery of million dollar mansions bought with donated cash helped push a lot of previously-excitable liberals into their quite and embarrassed era. To their credit, New York produced a couple investigative stories into BlackLivesMatter-related corruption, back when it was still somewhat risky to do so. Some people complained and, predictably, the journalist was called an Uncle Tom on Twitter. But there was a sense of the other shoe finally dropping, and before long people quietly removed the black squares from their Instagram profiles.

It’s that quote in my headline that gets to me, though: the embarrassed foundation that gave the dodgy nonprofit a lot of its funding, saying that it wasn’t upset that nothing was produced because it expected nothing, in an effort to save face. “We gave money to that racial justice nonprofit, but obviously we didn’t expect anything to come from it” is a perfect encapsulation of what the past four years have been like. From the widespread and angry insistence that society’s relationship to law and order was being actively rewritten, to a plain-faced admission that nobody really ever expected anything from the money that was being throw around…. Golly! It’s a shame that Bill Cosby is the figure most associated with the concept of the “soft bigotry of low expectations,” because that’s a very real thing that Black people very much have to labor under, made more toxic by the fact that it’s the supposedly most progressive white people who are most often guilty of it. I genuinely think “we gave money to this racial justice group but don’t worry, we knew they weren’t going to do anything with it so we’re not disappointed” is more insulting than a conservative hyperventilating about how BLM rioters are going to burn the whole country down. The latter attacks Black activists, in fear of their power; the former assumes away their power as an expression of ostensible respect. One thing that has not changed in the past four years is the preeminence of condescension in American racial discourse.

Dumb but fun: like so much contemporary art

Kamala Harris and the Black Elite

Black Republican Reihan Salam weighs in and makes some good points.

Over the course of her long career in elected office, Harris has not evinced many fixed ideological commitments. But she has been consistent in her adherence to “progressive racialism,” or the belief that the cause of racial justice demands a more vigorous embrace of race-conscious policy making. In the U.S. Senate and the White House, she has championed race-preferential college admissions and hiring programs, environmental-justice initiatives, and cultural-competency training, among other race-conscious policy measures. In this regard, Harris is representative of her class.

Shortly before the Supreme Court ruled against race-preferential college admissions in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina, a Pew survey found that although U.S. adults opposed them by a margin of 50 to 33 percent, Black adults favored them by a margin of 47 to 29 percent. However, this overall level of support masked a telling divide among Black respondents. Sixty-four percent of Black college graduates backed race-preferential admissions; support fell to 42 percent for Black respondents with some college or less. This wasn’t because a far larger number of non-college-educated Black respondents were opposed to race-preferential admission—it’s because a much higher share said they weren’t sure. …

[T]he impact of racial preferences on the life chances of Black Americans appears to have been negligible. Moreover, defending unpopular racial preferences may have made it more difficult to advance other policies that would have done more to foster Black upward mobility. Viewed through this lens, it is not surprising that many middle- and working-class Black voters are indifferent to the fate of race-preferential admissions, or that so many oppose them outright. …

As Black political unity starts to fade, Harris has a choice to make. Building on the policy agenda she developed for her 2020 presidential campaign and the record of the Biden-Harris administration, the vice president can champion the race-conscious policies that have proved so resonant among the progressive Black elite in the hope that doing so will inspire a renewed politics of Black solidarity. The challenge for this Talented Tenth approach is that the Black voters who have been most receptive to Donald Trump are younger and working-class. These are Black Americans who came of age in the 1990s and 2000s, against the backdrop of rising Black cultural and political influence. They are less embedded in the Black Church, an institution that has played a crucial role in inculcating norms of racial solidarity. And they are not embedded in the modern university, where racial identity and preferences have been most salient. In short, they seem skeptical of the profound racial pessimism so common on the progressive left.

Rather than lean into progressive racialism, Harris could seek to appeal to middle- and working-class voters of all groups, including disaffected Black voters, by downplaying race consciousness in favor of populist and patriotic themes, drawing on the lessons of Obama’s successful 2008 and 2012 campaigns. Doing so would make life more difficult for those of us on the right who oppose Harris’s vision for American political economy and our role in the world—but it would be an encouraging portent of racial progress to come.

Silicon Valley v Washington DC

Nice contrasting portraits of two cultures from Tanner Greer. There’s plenty more in the article if you want to click through to it.

I often draw a distinction between the political elites of Washington DC and the industrial elites of Silicon Valley with a joke: in San Francisco reading books, and talking about what you have read, is a matter of high prestige. Not so in Washington DC. In Washington people never read books—they just write them.

To write a book, of course, one must read a good few. But the distinction I drive at is quite real. In Washington, the man of ideas is a wonk. The wonk is not a generalist. The ideal wonk knows more about his or her chosen topic than you ever will. She can comment on every line of a select arms limitation treaty, recite all Chinese human rights violations that occurred in the year 2023, or explain to you the exact implications of the new residential clean energy tax credit—but never all at once.

The operatives and the media men of DC are of a different species. They will freely talk of anything, regardless of how much they know about it. But by and large the pundits and politicos are not intellectuals, and little intellectual work is expected of them. Those who love ideas for their own sake travel the path of the credentialed expertise.

Washington intellectuals are masters of small mountains. Some of their peaks are more difficult to summit than others. Many smaller slopes are nonetheless jagged and foreboding; climbing these is a mark of true intellectual achievement. But whether the way is smoothly paved or roughly made, the destinations are the same: small heights, little occupied. Those who reach these heights can rest secure. Out of humanity’s many billions there are only a handful of individuals who know their chosen domain as well as they do. They have mastered their mountain: they know its every crag, they have walked its every gully. But it is a small mountain. At its summit their field of view is limited to the narrow range of their own expertise.

In Washington that is no insult: both legislators and regulators call on the man of deep but narrow learning. Yet I trust you now see why a city full of such men has so little love for books. One must read many books, laws, and reports to fully master one’s small mountain, but these are books, laws, and reports that the men of other mountains do not care about. One is strongly encouraged to write books (or reports, which are simply books made less sexy by having an “executive summary” tacked up front) but again, the books one writes will be read only by the elect few climbing your mountain.

The social function of such a book is entirely unrelated to its erudition, elegance, or analytical clarity. It is only partially related to the actual ideas or policy recommendations inside it. In this world of small mountains, books and reports are a sort of proof, a sign of achievement that can be seen by climbers of other peaks. An author has mastered her mountain. The wonk thirsts for authority: once she has written a book, other wonks will give it to her.

The technologists of Silicon Valley do not believe in authority. They merrily ignore credentials, discount expertise, and rebel against everything settled and staid. There is a charming arrogance to their attitude. This arrogance is not entirely unfounded. The heroes of this industry are men who understood in their youth that some pillar of the global economy might be completely overturned by an emerging technology. These industries were helmed by men with decades of experience; they spent millions—in some cases, billions—of dollars on strategic planning and market analysis. They employed thousands of economists and business strategists, all with impeccable credentials. Arrayed against these forces were a gaggle of nerds not yet thirty. They were armed with nothing but some seed funding, insight, and an indomitable urge to conquer.

And so they conquered.

Giving money to poor kids improves their lives (and their incomes) SHOCK!!

The Potential Long-Run Implications of a Permanently-Expanded Child Tax Credit

Elizabeth Ananat and Irwin Garfinkel #32870

Abstract:For many of those who worked to include an expanded Child Tax Credit in the 2021 American Rescue Plan, an important motivation was to test the feasibility and effectiveness of a permanent U.S. child allowance similar to those provided in other rich countries. Because this expansion was short-lived, however, evaluations of its effects cannot provide complete evidence on the long-run effects of a permanently expanded CTC. We leverage theoretical predictions from standard economic models, behavioral science, and child development frameworks, along with empirical evidence from literature evaluating previous long-term cash and quasi-cash transfers to families with children, to predict the likely long-run impacts of a permanent child allowance. We find that it would lead to increased future earnings and tax payments, improved health and longevity, and reduced health care, crime, and child protection costs; using conventional valuations, benefits to society outweigh costs nearly 10! to 1, with most benefits due to credit refundability.

From another time only 16 years ago

What Is Postliberalism?

I enjoyed this hatchet job on post-liberalism. I quite liked Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed (hint: because it succeeded). I liked, and sympathised with his analysis of the way in which modern life had somehow disappeared into the ever shrinking space between Big Government and Big Commerce. But it was always hard to see how this could be tackled other than by reforming liberalism somehow — rather than turning away from it. Sure enough, now we can see the whites of post-liberalism’s eyes, it’s an ugly and unappealing beast. I can’t speak for the author of this piece from The Dispatch which describes itself thus:

Home for fact-based reporting and analysis on Politics, Policy, World Events, Religion, Culture, Economics, and Law informed by conservative principles.

But I did enjoy the tour.

In 2018, when I first began engaging in debates over what is today called “postliberalism,” more than a few of my fellow academics told me not to waste my time. In their view, it was an especially niche debate among a few mostly obscure and highly placed academic eccentrics.

But we should all care because postliberalism is now on the presidential ballot, and many of the same people I spoke to are scrambling to understand why and how. …

Put simply, postliberalism is three things. First, it is an authoritarian ideology adapted from Catholic reactionary movements responding to the French Revolution and, later, World War I. Second, it is a loose international coalition of illiberal, right-wing parties and political actors. Third, it is a set of policy proposals for creating a welfare state for family formation, the government establishment of the Christian religion, and the movement from republican government to administrative despotism.

The third point might sound unhinged, but postiberals have come to object to liberalism. While most Americans know the term “liberalism” as a reference to a left-of-center ideology common among Democrats, the other common use is in reference to a political theory that prioritizes individual rights as a source of political authority and human flourishing. Postliberals believe this “classical liberalism” to be a disembodied secularizing (even satanic) force that uses the language of liberty of conscience, representative government, and constitutionalism to conceal the true liberal aim of denying the authority of the highest good. In their view, liberalism has presently fallen apart, and there is now no need to “conserve” classical liberalism as movement conservatives like William F. Buckley Jr. to Milton Friedman and Ronald Reagan had argued.

On the contrary, postliberals want to end liberalism and entirely replace it with what comes next—what is literally “postliberal.” Given that liberalism entails liberty of conscience, representative government, and a constitution, none of those will be part of a postliberal order. Citizens will become subjects. Personal liberty gives way to bureaucratic discretion. Market economies are replaced by an alliance of corporate and state power.

What does that mean in policy terms? If Donald Trump wins the presidency again in November, does that mean we could be one election away from a postliberal America? The answer is, for postliberals, eventually. Postliberals have adopted a long game, believing that they will not secure policy wins all at once but rather one at a time. For example, family policy might wed middle-class voters to postliberalism like tax cuts once united them to movement conservatism. Family policy could thus become the leverage for future postliberal positions, such as giving China and Russia free hands in their spheres of influence. After all, why should America spend money defending Ukraine when the nation could spend that money on rebuilding the American family? This might sound far-fetched, but one should consider that recommendations for a middle-class welfare state and opposition to Ukraine are coming from postliberals, who are repeating messages from Viktor Orbán in the process. This is not speculation but their stated position.

Much of this is new to many ordinary American conservatives, but these arguments are actually quite old and have unpleasant roots. …

Postliberalism in the 20th century.

World War I ended reactionary hopes for the restoration of the monarchies of the past. Many monarchists shifted to becoming “integralists” or rightwing revolutionaries who hoped to establish modern states with a Catholic dictator overseeing bureaucratic administration. The ideological architect for this project was mid-19th century Spanish monarchist Juan Donoso Cortés, but much of his work had become obscure until Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt resuscitated it in his critique of the Weimar Republic and, eventually, his support of the Third Reich. In 1923, Schmitt saw in the papacy the last remaining example of a person who both represents the church in that he speaks for it but also in that he is the church in his person:

The political power of Catholicism rests neither on economic nor on military means but rather on the absolute realization of authority … the Church is a concrete personal representation of a concrete personality … But it has the power to assume this or any other form only because it has the power of representation. It represents the civitas humana. It represents in every moment the historical connection to the incarnation and crucifixion of Christ. It represents the Person of Christ Himself … The Catholic Church is the sole surviving contemporary example of the medieval capacity to create representative figures.

This treatment of the papacy echoes his 1921 book Dictatorship, wherein Schmitt affirmed that the dictator requires “personal representation.” Modern liberal states, in Schmitt’s view, expose their people to a constant struggle over power that only a dictator could settle. In the same way that the pope speaks as the final authority in the Catholic Church, so does the dictator speak as final authority on national affairs.

What does contemporary postliberalism look like?

How did postliberalism move from fringe Catholic ideology to the GOP vice presidential nomination in less than a decade in the person of Sen. J.D. Vance? After all, most Americans do not want what historical postliberals have proposed. To explain requires understanding how postliberals aimed to move from developing an ideology to creating an elite movement. On the ideological front, Notre Dame legal scholar Patrick Deneen has done much to break with the old Judeo-Masonic conspiracy by attributing the problems of liberalism not to shadowy conspirators but to the inevitable consequences of adopting liberal principles in law, culture, and economics. Liberalism becomes “structural” for postliberals the same way racism is for critical race theorists—the system itself is the source of the problem. That said, not all postliberals have opted for Deneen’s “structural turn,” as some stricter integralists, Alan Fimister and Fr. Thomas Crean, for example, have defended denying Jews and Muslims citizenship.

Vance has shown much more interest in Deneen’s position than Fimister’s and Crean’s. That said, there is still plenty of continuity between the older and contemporary postliberals. Legal scholar Adrian Vermeule regularly cites Veuillot and Schmitt. Political theorist Gladden Pappin likes to recommend the pamphlet, “Liberalism Is a Sin,” by antisemitic integralist priest Fr. Félix Sardà y Salvany. Recently, while appearing on Catholic Bishop Robert Barron’s Word on Fire program, Deneen even asserted that recent events had proven their anti-liberal positions right. He also included ex-Cardinal Louis Billot, who in 1927 surrendered his position as cardinal after refusing to leave the antisemitic French monarchist party Action Française.

But contemporary postliberals have not merely held conferences or written essays. They have conceived of a new ideology and political program to implement it.

In 2018, Vermeule argued for a 21st century approach to Pope Leo XIII’s 1884 call for French Catholics to participate as citizens in the French Third Republic. He called this “integration from within” wherein well-positioned Catholic integralists use their academic prestige to mint new integralist elites to influence public policy and run for office. They would then introduce Catholic integralism to the extent possible in a kind of right-wing “march across the institutions.”

Vermeule had a plan, but Pappin had institutional access. As a professor at the University of Dallas Pappin helped build a network of like-minded rightwing illiberals across Europe and the United States before eventually becoming president of the Hungarian Institute of International Affairs in Budapest. From there he brings American policymakers and academics to Hungary and Hungarian policymakers and academics to America. Pappin has since integrated Hungarian influence into conservative institutions such as the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, the Heritage Foundation, and even the leadership of the American Institute for Economic Research. Hungary has become something of a go-between for postliberalism and authoritarian regimes like Russia and China, with postliberals being among the loudest opponents of support for Ukraine and advocates for the Chinese model of economic corporatism and administrative oversight.

But the problem for them, at least in America, was always that while Donald Trump was good for demolishing the movement conservatism that had predominated in the GOP since the 1980s, the former president was an imperfect vessel for postliberal ambitions. …

What they needed was a politician of their own. That politician has turned out to be Vance, who converted to Catholicism in 2019. In a speech in 2022 at a postliberal event held at Franciscan University of Steubenville in Ohio, Vance mentioned that he had “admired … from afar” some of those in attendance while others he had “gotten to know very well over the last few years.” A year later, after winning his Senate seat, Vance admired them up close at the book launch of Deneen’s Regime Change, where he declared himself a postliberal. Vance has made many public statements backing postliberal public policies, such as granting greater voting power to parents of large families, and he has publicly praised Hungarian President Viktor Orbán as a model for effective conservative governance.

Even now, Vermeule is training conservative Harvard Law School graduates to adopt his negative view of the U.S. Constitution, as Mark Tooley discovered in a recent interview. The number of these postliberal elites will grow as the class of 2028 begins classes in a few weeks. It is filtering into some Catholic seminaries and has made its way into American Protestantism under the name of “Christian nationalism.” When my friends advised me to leave this alone in the hope that this nonsense would go away, they were wrong.

Busing to Opportunity? The Impacts of the METCO Voluntary School Desegregation Program on Urban Students of Color

Elizabeth Setren #32864

Abstract:School assignment policies are a key lever to increase access to high performing schools and to promote racial and socioeconomic integration. For over 50 years, the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO) has bussed students of color from Boston, Massachusetts to relatively wealthier and predominantly White suburbs. Using a combination of digitized historical records and administrative data, I analyze the short and long run effects of attending a high-performing suburban school for applicants to the METCO program. I compare those with and without offers to enroll in suburban schools. I use a two-stage least squares approach that utilizes the waitlist assignment priorities and controls for a rich set of characteristics from birth records and application data. Attending a suburban school boosts 10th grade Math and English test scores by 0.13 and 0.21 standard deviations respectively. The program reduces dropout rates by 75 percent and increases on-time high sc! hool graduation by 13 percentage points. The suburban schools increase four-year college aspirations by 17 percentage points and enrollment by 21 percentage points. Participation results in a 12 percentage point increase in four-year college graduation rates. Enrollment increases average earnings at age 35 by $16,250. Evidence of tracking to lower performing classes in the suburban schools suggests these effects could be larger with access to more advanced coursework. Effects are strongest for students whose parents did not graduate college.

If Your World Is Not Enchanted, You're Not Paying Attention

L. M. Sacasas at The Convivial Society. I think this piece is a little precious. I prefer people like Iris Murdoch’s more low key treatment of similar issues with her idea of ‘unselfing’. But it’s onto something important I think.

Disenchantment is one of the most venerable, and contested, concepts in the vast literature devoted to understanding the state of affairs we call modernity. The term was popularized by the eminent German sociologist Max Weber in the early 20th century. It is an English translation of a German word, Entzauberung, that means something like “de-magic-ifcation.” …

I am, of course, glossing a long and multi-faceted tradition of scholarship, which has more recently included arguments to the effect that we have never been disenchanted or that the world remains enchanted (although more like enchanting) if only we’re willing to embrace certain modes of being. The former position is staked out by Jason Josephson-Storm in The Myth of Disenchantment, and the latter claim is argued by Jane Bennett in The Enchantment of Modern Life. And while I do have my own lightly-informed positions on these debates, I certainly don’t intend to adjudicate them here.

Instead, I simply want to posit one idea for your consideration: Enchantment is just the measure of the quality of our attention. In other words, what if we experience the world as disenchanted because, in part, enchantment is an effect of a certain kind of attention we bring to bear on the world and we are now generally habituated against this requisite quality of attention?

In suggesting this correlation between attention and enchantment, I am partially endorsing Bennett’s argument that “the contemporary world retains the power to enchant humans and that humans can cultivate themselves so as to experience more of that effect.” Bennett, a political philosopher interested in the ethical dimensions of enchantment, which she treats more like a state of wonder, believes that enchantment is something “that we encounter, that hits us, but it is also a comportment that can be fostered through deliberate strategies.”

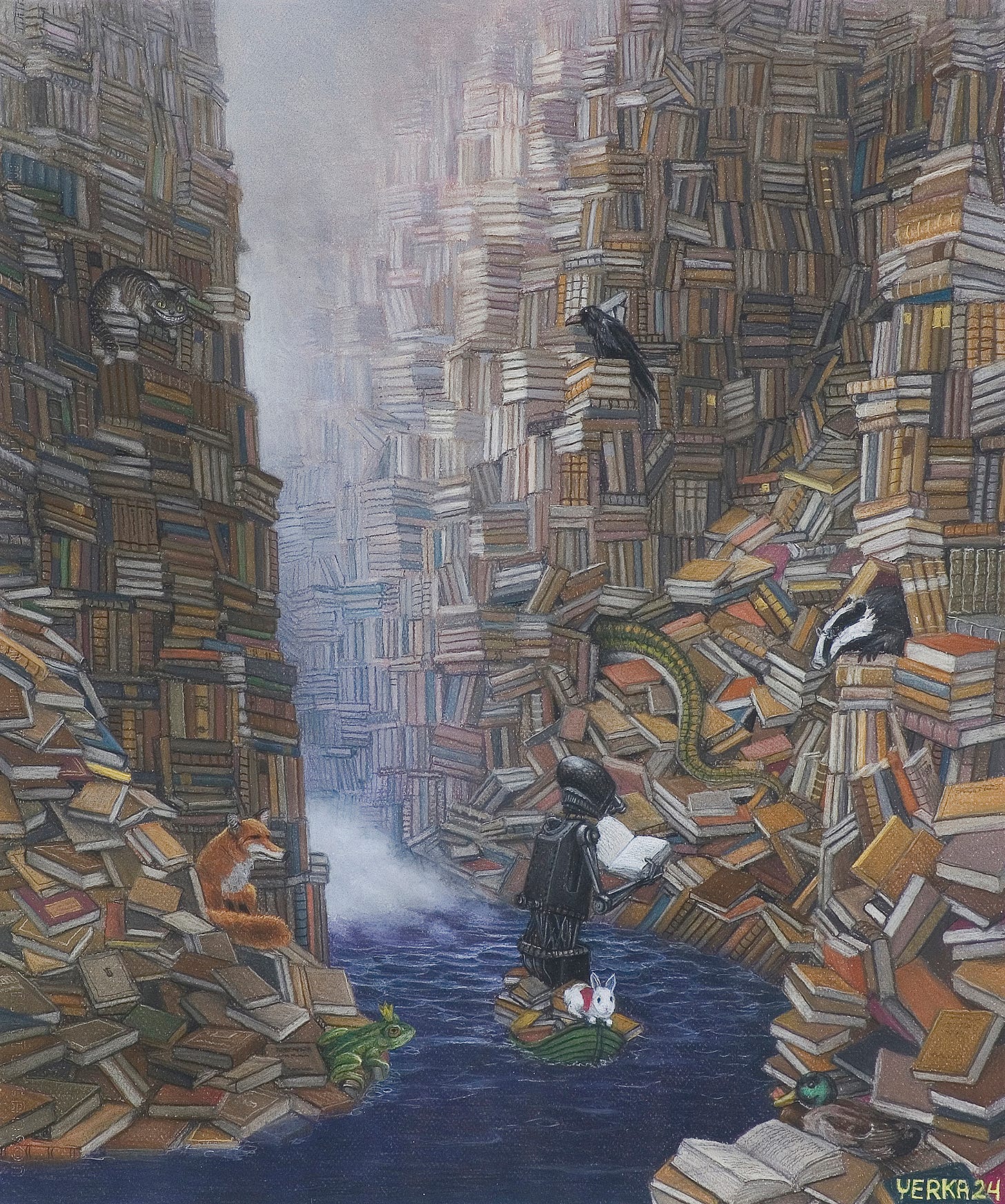

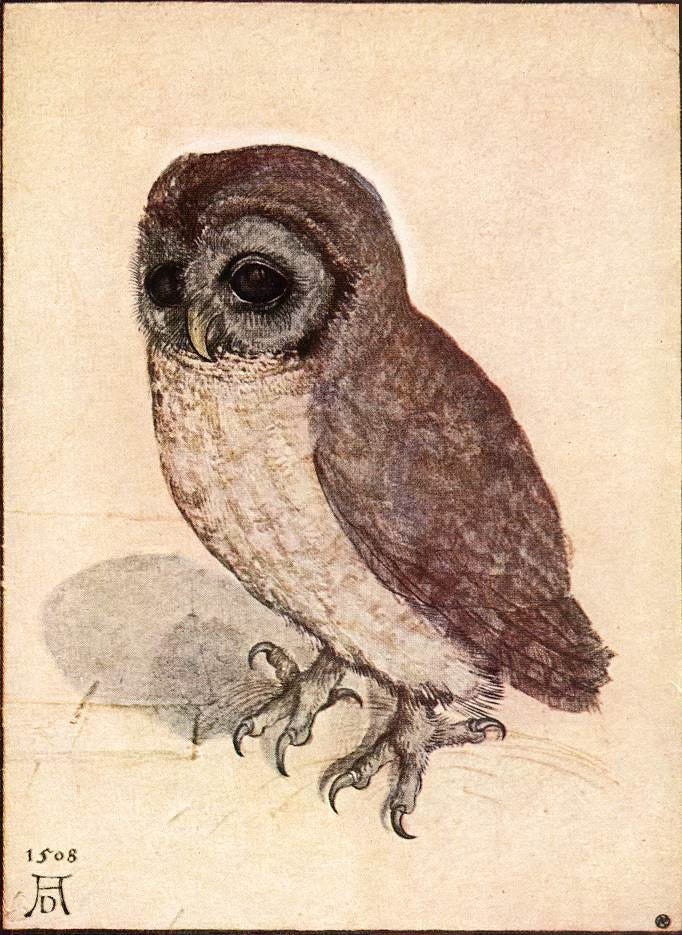

One of these strategies is “to hone sensory receptivity to the marvelous specificity of things.” I would argue that this is another way of talking about learning to pay a certain kind of attention to the world. In so doing we may find, as Andrew Wyeth once commented about a work of Albrecht Dürer’s, that “the mundane, observed, became the romantic”— or, the enchanted.

As the art historian Jennifer Roberts argued several years ago, “Just because something is available instantly to vision does not mean that it is available instantly to consciousness.” Or, as she also puts it, just because you have looked at something doesn’t mean that you have seen it. … According to Roberts, achieving this kind of knowledge and quality of experience requires “time and strategic patience,” which is a form of “immersive attention.”

To speak of attention in this manner, as a patient waiting on the world to disclose itself, recalls how Simone Weil insisted that attention is a form of active passivity. “We do not obtain the most precious gifts by going in search of them,” she insisted, “but by waiting for them.”

This form of attention and the knowledge it yields not only elicits more of the world, it elicits more of us. In waiting on the world in this way, applying time and strategic patience in the spirit of invitation, we draw out and are drawn out in turn. As the Latin root of attention [stretching towards] suggests, as we extend ourselves into the world by attending to it, we may also find that we ourselves are also extended, that is to say that our consciousness is stretched and deepened. And this form of knowledge is ultimately relational. It yields a more richly personal rather than clinical or transactional relation with the object known, particularly insofar as affection may be one of its consequences.

After all, attention can also be understood simply as the name for the contact the mind makes with the world, and, if it is sufficiently attenuated, our capacity and inclination to care, desire, love, and act also suffer. This, too, is one of the concerns animating Bennett’s explorations of enchantment. “You have to love life before you can care about anything,” she writes. “One must be enamored with existence and occasionally even enchanted in the face of it,” she adds, “in order to be capable of donating some of one’s scarce mortal resources to the service of others.”

In her view, the story we’ve been told about disenchantment already conditions us against the attention that we must necessarily bring to the world in order to perceive its enchanted quality. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy. … Habituated against attending to the world with patience and care, we are more likely to experience the world as a mute accumulation of inert things to be merely used or consumed as our needs dictate. …

The monasteries dissolved by Henry VIII

That’s a lot of monasteries!

Chapel of the Annunciation

Upon the gentle shoulder of a hill, which forms part of an estate of a Benedictine Priory, a Lady Chapel for the celebration of The Annunciation is proposed.

More here.

Heaviosity half hour

Lost in ideology

I really enjoyed this interview with Jason Blakely whom I’d not been aware of. It’s basic thesis is kind of obvious. It’s just that we behave as if we don’t know it. Ideologies are cultural products. And though to their adherents they feel like scientific theories and world making maps, they’re really visions of the good life. So, while the adherent can imagine they’re just being guided by the facts, they’re being guided as James Burnham argued, by wish fulfillment. So it’s hard to let go of them, and they’re even harder to credit that others with different ideologies might have just as good a point, and just as good a mind as you.

It led me to the book itself, the introduction of which is extracted below.

Introduction: in search of ideology

What is ideology? The answer is simple, if you do not think about it very hard. Ideology is politics in excess – distorted, immoderate and delusional. It is pundits shouting at each other and unruly mobs chanting in the streets. It is an uncle ranting about socialism at holiday dinners or a co-worker lowering his voice to whisper about the dangers of “the system”. Facts are of no avail when dealing with the victims of ideology; rational arguments slide off their brains like rain running down a granite dome.

As part of this, it has also become an unspoken rule to avoid describing your own politics as ideological. Respectable political ideas are best labelled a “belief system”, “theory”, “philosophy”, or even plain old “common sense”.¹ This is because your own politics are obviously reasonable and good, while those of an adversary are demonstrably irrational and false. If you are progressive, “ideology” is what coerces millions of people into conformity with inherited hierarchies and strips individuals of their freedom and well-being. If you are a conservative, “ideology” is a systematic attempt to replace the traditional moral order with faddish and radical ideas that eventually lead to societal decline and collapse. For both sides, escaping ideology is as simple as switching teams and adopting the one-and-only true and defensible politics.

The result of all this confusion and mutual accusation – as the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz brilliantly summed up – is “the term ‘ideology’ has itself become thoroughly ideologized”.² Ideology is a snake swallowing its own tail; it is an idea that consumes itself. Indeed, what many people think of as the obvious definition of ideology is nothing more than one more flower growing inside their ideological garden. Every time we seek to rein in ideology, we end up expanding its scope.

But why are we all so confident that our own convictions are immune to the very ideology plainly afflicting everyone else? This book begins from the deceptively straightforward claim that part of our problem is we have forgotten that politics is cultural. Instead, we have conferred natural or even quasi-scientific status on our own preferred vision of society. We are lost in ideology because our particular map (cartography) is mistaken for brutely given nature (geography). We are like those mapmakers in Jorge Luis Borges’s story, trying to draft a map of the empire that is the same size as the empire.³ Ideologies are akin to a map that carpets over the surrounding land point by point. When this happens, we no longer appreciate the difference between our hopes and visions for society and the inescapable realities of the world.

I will also try to show that ideologies are not merely distortive in this way but at the same time illuminating for interpreting and navigating social reality. As with maps, there is this dual, contradictory potential to ideology. Namely, ideology in the modern era both orients and disorients – one must learn to read its markings and symbols properly. This book is an attempt to teach readers how to get their bearings amid the major ideological maps and within the mapmaking project of ideology more generally. As we shall see, without ideology we would not be able to decode our own cultures or even ourselves.

THE TENDENCY TO LOSE OUR WAY

Historians believe that in 1626 Peter Minuit, Director of New Netherland, purchased the island of Manhattan from some members of the Lenape tribe for 60 guilders worth of trade goods like kettles, hoes and axes. The island that eventually became the hub for global capital was initially acquired not by military conquest, but by the seventeenth-century equivalent of a real estate deal. Such wheeling and dealing would have made perfect sense within the ideological world of Dutch market society, with its adage that “Christ is good, but trade is better”.⁴ But was it intelligible within the cultural coordinates of the Lenape tribe?

After all, historians have argued that the Lenape recognized a communal “right to hunt, fish, and plant within certain territorial limits” but did not practice the “sale or permanent alienation” of land “known to European law”.⁵ Instead, the Lenape likely saw themselves as accepting gifts from the Dutch, entitling the latter to some shared use of Manhattan. They almost certainly would not have thought they were making final transfer of the dwelling place of their ancestors.

Of course, some members of the Dutch trading company may have detected that the entire transaction was bogus and cynically proceeded with the sale all the same. But others likely suffered from an ideological blind spot that persists today: namely, that the transaction was the result of common sense and that they were simply smarter than the dupes on the other side of the negotiation table. The deal would have appeared to such individuals as sharp business acumen. If Rome had its Romulus, the North American colonies had countless Peter Minuits, transferring the enchanted tribal lands of the mythic ancestors into the commodity parcels of the business-savvy colonists. The era of ideologies had arrived to the New World.

In this way, the “Age of Discovery” was already one of profound ideological confusion. Like Borges’s mapmakers, the Dutch traders had unfurled their cartographic grid over all the territories and peoples of the New World, cutting off contact with the underlying indigenous culture. This experience of being disconnected from an alien culture is now nearly universal in our society, as we struggle to understand not a foreign tribe but our own neighbours, fellow citizens, colleagues and family members. Similar to the Dutch colonists, our own ideology seems to always arrive one step before us, as if it were an invisible carpet unrolling at our feet. As I will show in these pages, every ideological tradition is capable of generating this weird bewilderment – from conservatism to progressivism, nationalism to feminism. Ideology’s labyrinth exists inside every politics.

IDEOLOGIES AS STORIES AND MAPS

We are meaning-making animals and ideologies are stories about the significance or meaning of social and political life.⁶ This might sound like an uncontroversial claim. After all, who could reasonably deny that humans are meaning-makers seeking out the stories that most resonate with their own experiences? But one underappreciated consequence of this insight is that ideologies are cultural. They emerge from inside human language and history, and are not simply discovered within nature the way one spots the rings around Saturn or observes the migratory patterns of birds.

If ideologies are a form of meaning-making, then they are not so different from other forms of cultural production – theatre, literature, sports, cuisine, and music – that need to be understood through careful interpretation. Everyone knows that comprehending a rich story (say, one told by Homer or Shakespeare) requires a careful and patient art of interpretation. Yet comparatively few people are willing to lavish this kind of interpretive attention and generosity on ideology. This is especially true in cases where we find the other person’s ideology confusing, off-putting, or even morally repugnant. Instead, the common tendency is to dismiss a rival’s ideology as the product of some more basic mechanism like demographic identity, class interests, or even a psychological hang up.

Yet, if ideologies are stories, they cannot be fairly treated in this way but must be listened to on their own terms. As with a story, one gets the hang of an ideology and can grow more or less familiar with it by immersing oneself in interpreting its particular world, characters, language and plot. The more conversant one becomes in an ideology, the less likely one is to race to simplistic and reductive explanations. Likewise, the more conversant one becomes in multiple ideologies, the less prone one is to treat a favoured politics as natural or obvious.

In these pages I hope to help readers gain some fluency in a range of ideologies that are not their own. Each chapter is an attempt to achieve what Geertz called a “thick description” of an ideological tradition.⁷ Geertz was a master of the method of ethnography, in which researchers immerse themselves for months and even years in foreign cultures. He spent countless hours embedded in distant tribal cultures – in Bali, Sumatra and Morocco – patiently observing, listening and learning. “Thick description” was his name for an account of a culture nuanced enough to be recognized by its own adherents as faithful to it.

Today, thick description needs to be brought back home in order to understand our closest neighbours, who may be geographically near but have grown culturally very distant. For this reason, in these pages each major ideology is presented through its most articulate champions. This often means looking at texts in which an ideology was originally given voice by a formidable philosopher or theorist. These leading figures bring into language what ordinary rank-and-file members recognize as the most nuanced and enduring versions of their own politics.

Ideologies are stories but they can also be thought of as what Geertz called “maps of problematic social reality”.⁸ Such maps help orient people within political space – not merely existing as narratives on a page but guiding their actions and practices, helping them to move in the world. Ideologies, for better or worse, are powerful sense-making aids. Often when someone adopts an ideology, they have a deep experience of something going “click” and might even feel a kind of exhilaration, as they think: “Aha! Now I finally understand politics! I know what steps to take and in which direction!”⁹

As stories and maps, ideologies must be allowed to speak to some extent in their own voice. This can be difficult not only due to the effort and disorientation which thinking through a rival ideology requires, but also because all ideologies contain within them a call or effort at recruitment. Not listening to a rival is sometimes the easiest way to deal with this temptation from the other side. Avoiding a rival’s maps and stories also serves the political goal of establishing one’s own ideology as hegemonic. But as students of ideology, we must avoid such false certainties. We must be willing to keep our ears open to strange voices and tales, even if like Odysseus this means tying ourselves to the mast as the sirens sing their perilous songs.

IDEOLOGIES AS LIQUID AND WORLDMAKING

Ideologies are maps, but this metaphor has limits. After all, conventional maps are frozen snapshots of the world. There is a risk that if we picture ideologies as maps, we will assume they are similarly static. However, the truth is ideologies are liquid and always changing. The liquidity of ideologies means it is a mistake to attribute to them ahistorical, core features. Instead, as the great scholar of ideologies Michael Freeden observed, ideologies consist of “family resemblances”, with no single element remaining constant across all members.¹⁰ As we shall see, the result is there is not one liberalism but many liberalisms, not one conservatism but many conservatisms, not one socialism but many socialisms, and so on.

Liquids do not have hard edges or solid borders and neither do ideologies. They can mix and blend in unexpected ways. Indeed, many strange hybrids appear in these pages – fascists who go green; socialists who favour gradualism; conservatives who reject capitalism; and much more. Many people know culture can hybridize (fusion cuisines, hybrid sports, syncretized religions, cross-genre musicians, etc.), but when it comes to ideology, all awareness of this permeability vanishes. Rather, the dominant view of ideologies is as a uniform left–right spectrum in which only neighbouring ideologies resemble or overlap with one another. Yet this is false. Any ideology can mix with any other. But to see this, readers must learn to liquify ideology.

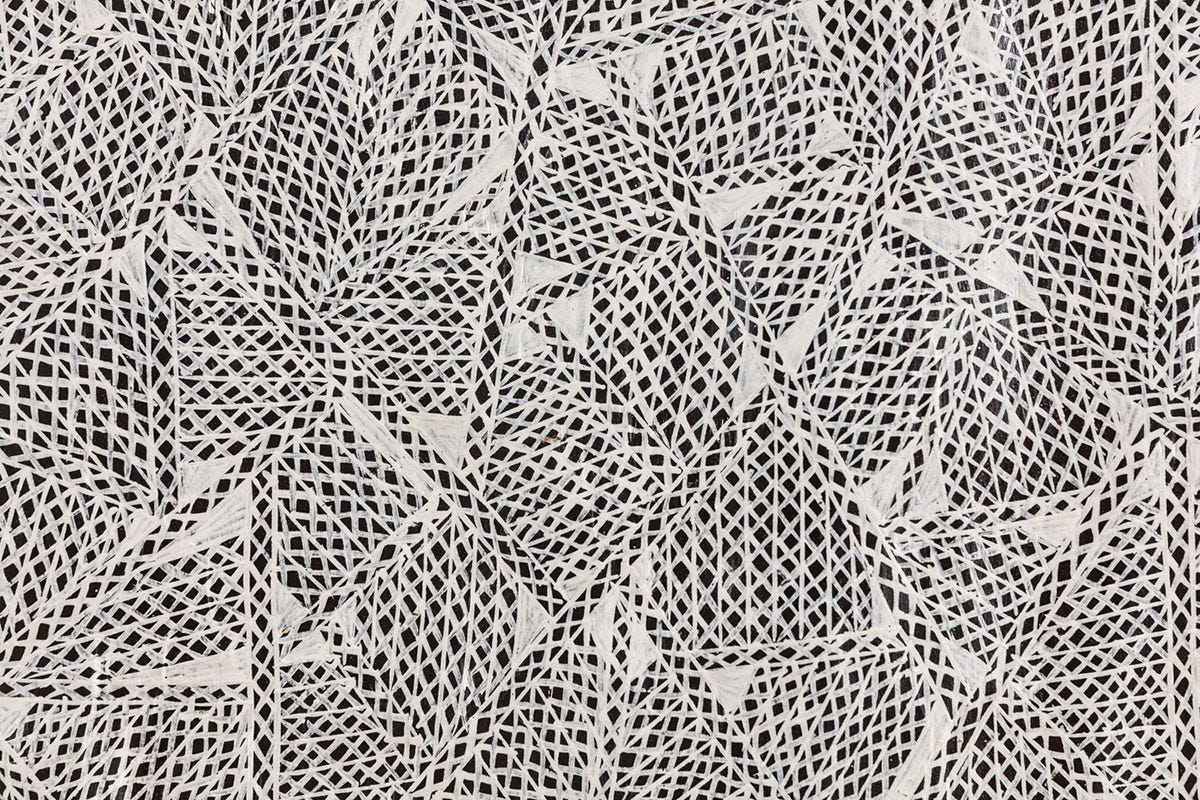

Instead of a rigid scale – with discreet intervals like beads running along a string – liquid ideologies are similar to the action paintings of Jackson Pollock. In Pollock’s complex splatter paintings, colours recur as drips, streaks and threads crisscrossing, weaving and bluring with other colours. A pattern of left to right may or may not emerge beneath the tumult, but the idea that left and right cannot combine in unexpected ways is a myth that contributes to the current disorientation.

In addition to rejecting the picture of ideologies as static, the metaphor of maps also needs to be updated to avoid thinking of ideologies as simply descriptive of a world “out there”. Conventional maps deploy symbols to represent a reality that is separate from what is on the page. If a cartographer edits a map of Yosemite, moving a peak or recharting a ridge, there is no way in which the mountains themselves stand up and move. By contrast, ideological maps always have the potential to reposition the very political landscape they sometimes appear to be describing. In other words, ideologies are worldmaking and a creative enough cartographer can move mountains if the multitudes join in putting their backs into the work.

Ideological maps, therefore, conjure forth and help build social reality.¹¹ This is because ideological meanings and symbols can be embodied in practices, institutions, laws, economies, regimes, and forms of self. A common way to become lost in ideology is when everything in a social world reflects it back as natural. The map made the world and everything appears to correspond with it. Under such conditions, alien ideologies become more unreal than science fiction and stranger than hieroglyphs. The home ideology, by contrast, functions like an all-encompassing matrix. The map holds everybody captive because they live inside of it.

IDEOLOGIES AS MAGNETIC AND DISENCHANTED

Why do people fall so hard for ideology? Why are they capable of tearing up friendships and families, forming new communities, embarking on mass migrations, sacrificing wealth, suffering physically, or even spilling blood for these maps? After all, the history of ideology reveals lands littered with bodies. Every ideological map has at one time or another been drawn in the red ink of massacres.

The answer lies in the fact that ideologies are worldmaking and guide us at the largest scale. They are not outside of material reality but organize it – money, prizes, status, health and other goods. They also encompass loftier goals of justice, honour, recognition and even holiness. Whether wrongly or rightly, anything that we care about might be given space, or violently stamped out, by a given ideological programme. Likewise, even mundane emotions, desires, aspirations, and fears can be grafted into its matrix. Thus, the stakes of ideology are exceptionally high.

Ideology always proposes some vision of a good society with our life at its service. When one is attracted to an ideology there is an intense ethical magnetism to it. Indeed, many people fall for ideology similarly to falling in love or converting to a religion. This also suggests why suspending belief in one’s own ideology (in order to listen to a rival) is so difficult. After all, is detaching in this way not a betrayal? Does it not threaten justice and unmoor one’s sense of self? Ideologies come with their own missions, vocations, preachers, pastors and zealots.

At the same time, ideology’s intense magnetism does not exclude the possibility that individuals can experience alienation or dry spells. As with religious faith, adherents can continue going through the motions without believing very intensely anymore. It is even possible to sit in the doorway of an ideology and strike an aloof, ironic pose, without actually leaving the building.¹² None of this changes – and, in fact, presupposes – the truth that ideologies radiate an intense magnetic pull.

Religions and ideologies share deep moral sources, but the similarity can also be overstated. After all, the world religions are millennia older than the major ideologies. In fact, our modern ideologies are the product of what the philosopher Charles Taylor calls a secular age, occurring in an “immanent frame”.¹³ When it comes to politics, Taylor has shown at length that people today self-consciously mobilize within immanent historical time. By contrast, many premodern people believed spirits, gods, and supernatural entities established and maintained their regimes, regardless of any human efforts. Such a view is expressed by the captain in Shakespeare’s Richard II who reports seeing “signs” that “forerun the death of kings” including “withered” trees, “meteors” and the moon turned “bloody” red.¹⁴ Sure enough, a few acts later, King Richard is dead.

By contrast, modern ideology (even when religious) self-consciously occurs inside historical time. Religious conservatives and traditionalists today do not expect the moon, trees and meteors to act or signal on behalf of their politics. Ideologies are in this specific sense disenchanted – mobilizing followers around programmes led by human, all-too-human efforts to get them off the ground. The pattern of politics typical of the French Revolution, with the theorizing of ideas and rallying behind them, is now universal. Granted, the liquidity of ideologies allows them to sometimes absorb and coopt an older religious tradition in its entirety. When this happens, religion continues to exist like the lost city of Atlantis, submerged at the bottom of an ideological ocean.

CHARTING A PATH FORWARD

Because ideologies are fraught with danger, many try to steer clear of them altogether. Such people believe themselves to be “non-ideological” and “not political”. However, the attempt to escape ideology by this route is a false solution to a real problem. We cannot opt to be “ideology-free” because in doing so, we simply continue participating in the dominant ideologies without awareness. Modern society is itself a living artifact of various competing ideologies. To proclaim oneself beyond ideology is the surest sign that one is adrift in it.

Other people instead attempt to inoculate themselves against ideology by proclaiming they believe in nothing more than science, data and logic. Admittedly empirical facts and logic do exert some critical force over ideology (I shall sometimes draw on their authority in these pages). For example, science has an important role to play in establishing inconvenient facts that may contradict a particular ideology. Similarly, logicians can do damage to an ideology by diagnosing its inner inconsistencies.

Unfortunately, however, these approaches only take us so far in the realm of ideology. As I shall try to show, most of the major ideologies are not so easily defeated (or vindicated). This is because ideologies are visions of a good society that always go beyond the merely factual and logical to pose basic questions of meaning and significance. As such, they cannot be settled by empirical or logical claims alone. They instead require a broader conception of reason that includes the interpretive rationality of the storytelling disciplines. Part of settling ideological disputes involves deciphering the meaning or significance of political life. This is far from relativistic. We continually hold people accountable for stories that are interpretively inferior accounts of the meaning of something or else generate an ethically undesirable account. These are precisely the sorts of debates central to disciplines in the humanities like literature, religion, the arts and history.

For example, one important form of criticism I shall make of ideology that draws on these disciplines is the idea of self-narration. I shall argue time and again that a given ideology is inferior because it cannot tell its own story as cultural, instead claiming to somehow be natural, common-sensical, or scientific. Conversely, ideological variants from across different traditions that do not fall into this trap, can at least claim superiority to their rivals in this key regard. My account of ideology is therefore attentive to what followers of a given programme think, without falling into uncritical relativism. I shall draw on philosophical analysis, the natural sciences, and most of all the storytelling disciplines with their art of interpretation, to critique ideology. By the end, perhaps readers will have a clearer sense of what they find reasonable and ethically attractive in rival ideological maps.

Thus, we set out on our journey into ideology with an orienting philosophical compass. Ideologies are not simply the crazed beliefs of your political foes. They are cultural traditions; they are world-making maps; they are liquid, narrative and ethically magnetic visions. While ideologies share some similarities with religions they also belong to our disenchanted and modern age.

We begin from the context of the United States, not because it is universal, but because all cultural investigation must start from some location. My hope is, however, to move outward towards a more global vision. The first two chapters engage the ideologies of the American founding, including not only classical liberalism and civic republicanism but also white supremacy. The middle chapters explore the hyperpolarization of left and right including progressive liberalism, right libertarianism, conservatism, fascism, socialism and communism. The final cluster of chapters dives into ideologies that scramble the whole notion of a clean split between left versus right, such as nationalism, multiculturalism, feminism and ecologism. I conclude reflecting on what it means to live in an ideological age and how to argue about ideological differences in a way that is critical, objective and not reductive or dismissive.

While I do not offer a complete account of any one ideology, I do attempt to orient readers within the upheaval and tumult of the competing maps. No ideology comes out unscathed. Cultural awareness of ideologies highlights inner tensions and dilemmas – I call out all the ideological traditions whenever they claim the false status of nature or science. I also attempt to fairly identify their deeper moral sources and affirm why they can resonate so powerfully for their followers.

Although the book is meant to be read cover to cover, readers can also jump to those chapters treating ideologies that most interest them and which they hope to see illuminated and criticized by cultural interpretation. My hope is that the reader will fall slightly less in love with their own ideology, and have a more nuanced, if still critical understanding of one that is not their own. The failure to do so could leave us lost in a map so big it conceals the world.

Option D at the Tax Summit

That heading is a stupid inside joke for friends of mine who were around at the time of Bob Hawke’s 1985 Tax Summit. I’m surprised Tony Abbott didn’t promise it along with Direct Action to replace carbon pricing, but I guess the moment had passed.

I've sometimes wondered if South/North American attitudes to race are in part a function of the period in which they were (predominantly) colonised: Pre/Post Linnaean taxonomy.