Diseases of the Intellect

And other things I discovered on the net this week

Diseases of the intellect

A post by that name by Alan Jacobs. I’m quoting it at greater length, because this was as short as I could make my extract and still convey the meat of the argument. I liked the meat of the argument. Like the Moliere character who discovered he’d been speaking prose his whole life, I think I’ve been battling diseases of the intellect my whole life. My own and others, all whipped up by our relentlessly optimised and now weaponised cultural, political and intellectual landscape.

Twenty years ago, I had an exceptionally intelligent student who was a passionate defender of and advocate for Saddam Hussein. She wanted me to denounce the American invasion of Iraq, which I was willing to do. … That is, her denunciation of America as the Bad Guy was inextricably connected with her belief that there simply had to be on the other side a Good Guy. …

This student was not a bad person — she was, indeed, a highly compassionate person, and deeply committed to justice. She was not morally corrupt. But she was, I think, suffering from a disease of the intellect. … Certain writers are highly concerned with these mental states, and the genre in which they tend to describe them is called the Menippean satire. … In his Anatomy of Criticism, Northrop Frye wrote,

The Menippean satire deals less with people as such than with mental attitudes. Pedants, bigots, cranks, parvenus, virtuosi, enthusiasts, rapacious and incompetent professional men of all kinds, are handled in terms of their occupational approach to life as distinct from their social behavior. The Menippean satire thus resembles the confession in its ability to handle abstract ideas and theories, and differs from the novel in its characterization, which is stylized rather than naturalistic, and presents people as mouthpieces of the ideas they represent…. The novelist sees evil and folly as social diseases, but the Menippean satirist sees them as diseases of the intellect.

Thus the title of my post.

I think much of our current political discourse is generated and sustained by such screening, screening that an age of social media makes at once more necessary and more pathological. Also more universally “occupational,” because in some arena of our society — journalism and the academy especially — the deployment of the correct conceptual screens becomes one’s occupational duty, and any failure so to maintain can result in social and professional [ostracism]. And that’s how people, and not just fictional characters, become “mouthpieces of the ideas they represent.” …

It’s surprising how powerful people’s conceptual screens are, how impervious to attack. But maybe it shouldn’t be surprising, since those screens are the primary tools that enable us to “mean only one thing” to ourselves; they allow us to coincide with ourselves in ways that soothe and satisfy. The functions of the conceptual screens are at once social and personal.

All this helps to explain why the whole of our public discourse on Israel and Palestine is so fraught: the people participating in it are drawing upon some of their most fundamental conceptual screens, whether those screens involve words like “colonialism” or words like “pogrom.” But this of course also makes rational conversation and debate nearly impossible. The one thing that might help our fraying social fabric is an understanding that, when people are wrong about such matters — and that includes you and me — the wrongness is typically not an indication of moral corruption but rather the product of a disease of the intellect. …

With all that said, here are some concluding thoughts:

A monolithic focus on assigning blame to one party while completely exonerating the other party is a sign of a conceptual screen working at high intensity.

Such a monolithic focus on blame-assignation is also incapable of ameliorating suffering or preventing it in the future. (Note the use of the italicized adjective in these two points: the proper assessment of blame is not a useless thing, but it’s never the only thing, and it is rarely the most important thing, for observers to do.)

If you are consumed with rage at anyone who does not assign blame as you do, that indicates two things:

you have a mistaken belief that disagreement with you is a sign of moral corruption, and

your conceptual screen is under great stress and is consequently overheating.

It is more important, even if it’s infinitely harder, for you to discover and comprehend your own conceptual screens that for you to see the screens at work in another’s mind. And it is important not just because it’s good for you to have self-knowledge, but also because our competing conceptual screens are regularly interfering with our ability to develop practices and policies that ameliorate current suffering and prevent future suffering.

A possible strategy: When you’re talking with someone who says “Party X is wholly at fault here,” simply waive the point. Say: “Fine. I won’t argue. So what do we do now?” Then you might begin to get somewhere — though you’re more likely to discover that your interlocutor’s ideas begin and end with the assigning of blame.

Niko Tiliopoulos

I know nothing of this case. But here’s the situation from one of the best read philosophy blogs on the net.

They’re trying to fire my friend Niko Tiliopolous. Despite his research output and teaching quality, they’ve been trying to fire him for some time for a variety of reasons. They’ve taken so much of his energy. Now they’re giving him a choice- literal, physical death, or the destruction of the life he has built for himself as a scholar. You can sign the petition against this monstrosity here.

Niko is immunocompromised. His lungs are badly damaged, and he has been told, by no less than three specialists, that if he catches COVID he will die- indeed a cold or flu might finish him off … The University - by which I mean its administrators - has decided this is insufficient. Ultimately he’s just a point they want to prove, part of a broader war on working from home. Now I get the desire to make university lectures in person - campus life, intellectual and otherwise- is important. But there’s no consideration of the special circumstances of the case, no willingness to compromise by, for example, shifting his duties away from teaching or letting him teach from home on the basis of reasonable accommodations.

I wish I could fire management instead. They’re not really the university. We are the University. They live parasitic off our energies. They’re an occupying force.

And these passages made me newly grateful I didn’t follow my father into academia. Back then it was a wonderful, functioning institution.

A philosopher I very much respect told me recently: “You can’t publish anything anymore without a hundred references and a four thousand word literature review attached that is polished and shiny and deals with fourteen objections no one would bother to make anyway. It’s impossible to just publish an interesting idea now. The first half of every paper isn’t even worth reading, it’s just there to show the author is a very serious person who should be published in a very serious journal”.

The new scholars I meet- postdocs-, new philosophers mostly, they’re lovely. But I can’t help but notice that they’re not as eccentric as their forebears. As competition for spots in academia becomes more fierce, the, for want of a better word, neurodivergent are being pushed out. The strange people who wanted to change the world, or dig deep into reality, were replaced by those seeking a career. It’s just a simple dichotomy, of course, many force themselves into the mold of careerists, trimming the wings for Blakean mind flight.

Good interview on Gaza

Identity politics of the 17th century

Or is that identity theology?

From Curiosities of Puritan Nomenclature, by Charles W. Bardsley

One of the strongest indictments to be found against this phase of Puritanic eccentricity is to be found in Hume’s well-known quotation from Brome’s “Travels into England”—a quotation which has caused much angry contention. The book quoted by the historian is entitled “Travels over England, Scotland, and Wales, by James Brome, M.A., Rector of Cheriton, in Kent.” Writing soon after the Restoration, Mr. Brome says (p. 279)—

“Before I leave this county (Sussex), I shall subjoin a copy of a Jury returned here in the late rebellious troublesome times, given me by the same worthy hand which the Huntingdon Jury was: and by the christian names then in fashion we may still discover the superstitious vanity of the Puritanical Precisians of that age.”

A second list in the British Museum Mr. Lower considers to be of a somewhat earlier date. We will set them side by side:

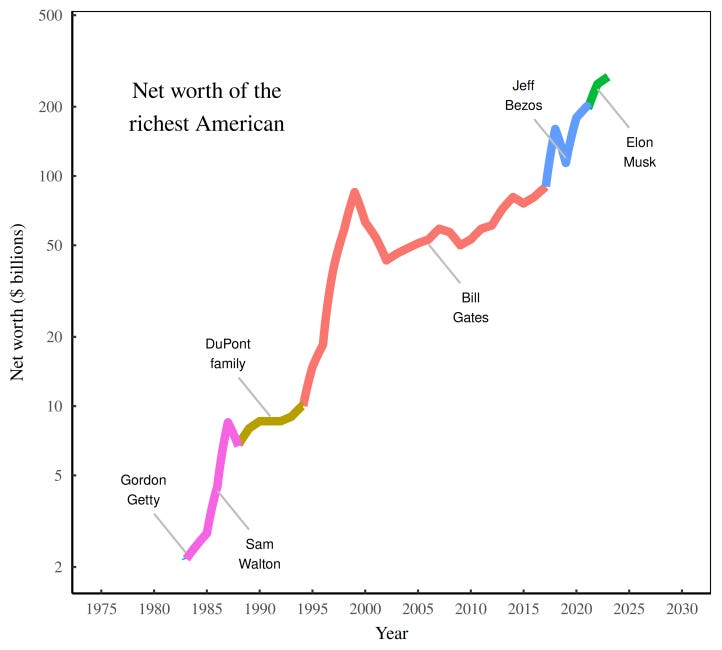

Life among the uber rich

Fractal inequality

Now that we’ve watched the game of thrones among the three richest Americans, let’s return to the rise of wealth inequality. Since the 1980s, the wealthiest Americans have gotten richer, both in dollar terms, but also relative to other Americans.

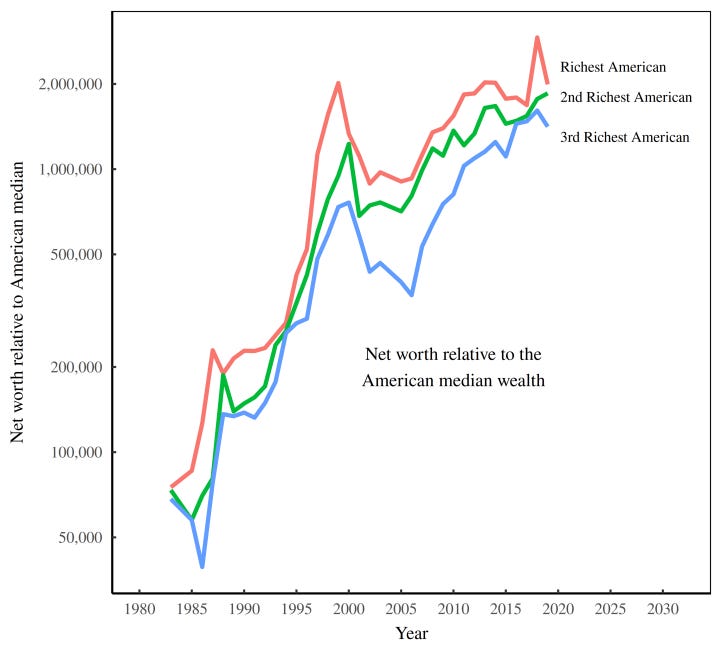

Figure 5 shows one way to look at the pattern. The colored lines plot the net worth of the three richest Americans, measured relative to the American median wealth. The trend may look linear, but don’t be fooled. The vertical axis uses a log scale. Since 1983, the relative net worth of the richest American increased by about a factor of forty. The second and third spots were not far behind

.So in modern American, the rich have gotten richer relative to the average person. But that’s not all. It turns out that there’s a fractal pattern to this rising inequality. No matter where we look, we find that the rich have pulled away from their less-fortunate brethren.

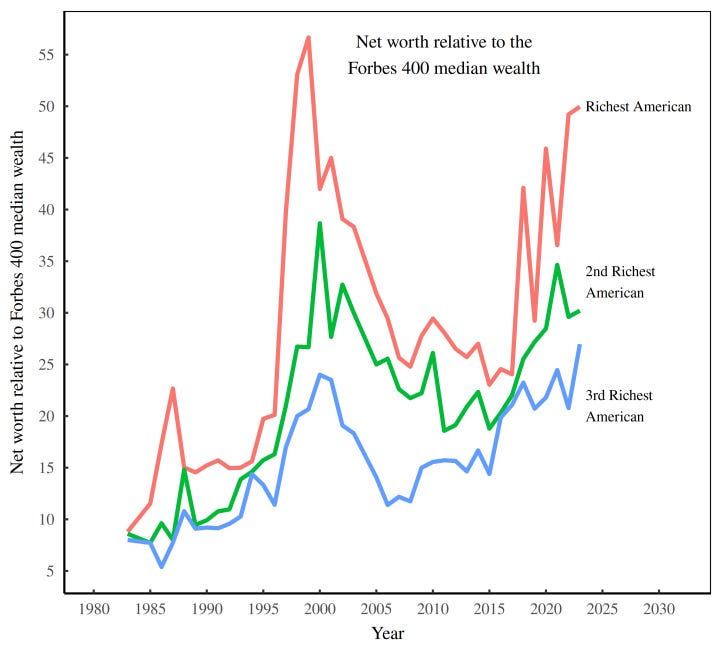

Take the Forbes 400 as an example. By any reasonable standard, every member of the Forbes 400 is jaw-droppingly rich. Yet even within this menagerie of elites, the rich have gotten richer.

Figure 6 shows the trend. Again, the colored lines plot the net worth of the three richest Americans. But check out what their net worth is pegged against. That’s right, I’ve plotted the net worth of the three richest Americans relative to other extremely rich people — in this case, the median wealth of the Forbes 400.

Let’s have a taste of some of these numbers. In 1983, the richest American was worth about 10 times more than the median member of the Forbes 400. Fast forward to 2023, and that value has increased to a factor of 50. Let’s say that again. Elon Musk is so rich that he’s 50 times richer than the Forbes 400 median. (And that’s not even the most extreme observation. In the late 1990s, Bill Gates was over 55 times richer than the Forbes 400 median.)

And on it goes.

Celebrity corner

The entire staff of this newsletter had a ‘week of mindfulness’ retreat to work out how we could further exceed reader expectations to meet our mission, which, as you know is “leveraging our unique assets and diversity to realise heaven on earth — and then a bit later on in heaven”. Anyway, a “celebrity corner”, was a bit of a no-brainer so here it is. Quite fun.

Democratic murder

Patricia Evangelista is interviewed on the Newyorker Radio Hour about her book Some people need killing on the reign of democratic murder in her country.

I’m a proud investor in this venture

John Mearsheimer from 2017

I’m a Black Professor. You Don’t Need to Bring it Up

I covered Tyler Austin Harper’s review of the rise and fall of Ibram X. Kendi last week. Here’s some more in the same vein.

As a Black guy who grew up in a politically purple area—where being a good person meant adhering to the kind of civil-rights-era color-blindness that is now passé—I find this emergent anti-racist culture jarring. Many of my liberal friends and acquaintances now seem to believe that being a good person means constantly reminding Black people that you are aware of their Blackness. Difference, no longer to be politely ignored, is insisted upon at all times under the guise of acknowledging “positionality.” Though I am rarely made to feel excessively aware of my race when hanging out with more conservative friends or visiting my hometown, in the more liberal social circles in which I typically travel, my race is constantly invoked—“acknowledged” and “centered”—by well-intentioned anti-racist “allies.” …

My point is not that conservatives have better racial politics—they do not—but rather that something about current progressive racial discourse has become warped and distorted. The anti-racist culture that is ascendant seems to me to have little to do with combatting structural racism or cultivating better relationships between white and Black Americans. … No, at the core of today’s anti-racism is little more than a vibe shift—a soft matrix of conciliatory gestures and hip phraseology that give adherents the feeling that there has been a cultural change, when in fact we have merely put carpet over the rotting floorboards. …

Yet, although anti-racist academics and activists are right to argue that race-neutral policies can’t solve racial inequities—that supposedly color-blind laws and policies are often anything but—over the past few years, this line of criticism has also been bizarrely extended to color-blindness as a personal ethos governing behavior at the individual level. …

Writing in 1959, the social critic Philip Rieff argued that postwar America was transforming from a religious and economic culture—one oriented around common institutions such as the church and the market—to a psychological culture, one oriented around the self and its emotional fulfillment. By the 1960s, Rieff had given this shift a name: “the triumph of the therapeutic,” which he defined as an emergent worldview according to which the “self, improved, is the ultimate concern of modern culture.” Yet, even as he diagnosed our culture with self-obsession, Rieff also noticed something peculiar and even paradoxical. Therapeutic culture demanded that we reflect our self-actualization outward. Sharing our innermost selves with the world—good, bad, and ugly—became a new social mandate under the guise that authenticity and open self-expression are necessary for social cohesion. …

When anti-color-blindness and its ideology of insistent “race consciousness” are translated into the sphere of private life—to the domain of friendships, block parties, and backyard barbecues—they assault the very idea of a multiracial society, producing new forms of racism in the process. The fact that our media environment is inundated with an endless stream of books, articles, and social-media tutorials that promise to teach white people how to simply interact with the Black people in their life is not a sign of anti-racist progress, but of profound regression. …

The subtext that undergirds this new anti-racist discourse—that Black-white relationships are inherently fraught and must be navigated with the help of professionals and technical experts—testifies to the impoverishment of our interracial imagination, not to its enrichment. The subtext that undergirds this new anti-racist discourse—that Black-white relationships are inherently fraught and must be navigated with the help of professionals and technical experts—testifies to the impoverishment of our interracial imagination, not to its enrichment. More gravely, anti-color-blind etiquette treats Black Americans as exotic others, permanent strangers whose racial difference is so chasmic that it must be continually managed, whose mode of humanness is so foreign that it requires white people to adopt a special set of manners and “race conscious” ritualistic practices to even have a simple conversation.

Three Scotts who’ve graced Australian popular Music

I was at lunch with some friends yesterday when someone mentioned Jimmy Barnes — a Scott who made good in Australian popular music. It put me in mind of two others. Colin Hay and Eric Bogle. I’ve been to several concerts of both and they’re magnificent. Both are very Scottish and very funny.

Tyson Yunkaporta on enlightenment and a chat with me

From Tyson’s latest book. And it’s on audible read in Tyson’s dulcet and deep tones.

Belongings: Can I keep all my stuff in the Anthropocene?

There are black clouds across the sky and the dry sclerophyll forest is quiet here, where I sit chipping away at a piece of dark wood, trying to remember how I used to do this. I panic for a moment when I realise I’ve lost my innate sense of direction. I know the track is north of here because I went off to the south earlier, following a wombat. But all of a sudden I’m not sure which way is north, and in this state of mind I wouldn’t know if the scat on the log beside me belonged to a wombat, a dingo or a feral mountain lion.

If I can’t re-orient myself, I’ll just call out and Pete McCurley will call back so I know which direction the camp is. I’m staying with that Gumbaynggirr genius for a bit while my reluctant muse Megan generously shoulders the load of domestic duties and childcare so I can try to straighten my head out, because her two sisters are starting to think I’ve lost my mind.

Our canoe is resting in an exhibition somewhere: somebody wanted to curate a sexy counterpoint to the colonial nostalgia of the other works on display there.

So now I’m making a war boomerang for the Enlightenment, to add to the tools we might keep in our canoe as we head upstream. It’s made of yarran wood from Wilcannia in New South Wales, red and hard as hell, from a part of the world where war boomerangs have always been massive and fearsome. It was a huge piece of wood when I started it, but I’ve been chipping away all the bits of the Age of Reason that contain world-terminating algorithms and I have to tell you it’s getting a bit thin. It’s a work in (about) progress. I’m worried that by the time I’m finished it’s just going to be a pile of wood chips I’ll have to carry around in a bag.

This is my first day away in ages, here in this little shack on Djadjawurrung Country in a beautiful forest full of wombats. Melbourne’s been in Covid lockdown for most of the last two years, and I’ve been getting fat and growing psychoses like tumours while the universities remain closed to most staff and my woman and I work from home and raise vigorously neuro-divergent babies and take each twenty-hour day as it comes. Our extended families are in turmoil too and there are frequent horrendous events, but we can’t get back home to help, so we just coordinate bills and bail and beds and bandages from our phones and wallets.

I can’t remember the last time I saw stars like this, without the miracle of metropolitan light smearing the night sky into a murky void. I’ve got a little fire out the front of this shack and I was able to smoke myself with gum leaves and acacia today after taking an axe to progress; that smoke went right through me and washed away some of the toxic build-up of the last two years. The nearest toilet is a fair hike through the scrub to one of those outback sheds that looks like it’s got fifty backpackers buried under it, and that’s no fun when you’re belly-sick at four in the morning. It’s been a while since I ate bully beef out of the tin.

My body is soft and sick, and I find myself vaguely longing for the mushy comforts of modernity for the first time in my life. I’m practically a child of the Enlightenment myself these days. I even got to rewrite the libretto in Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, for Simone Young to conduct at the Sydney Opera House. I’m firmly wedged between the cheeks of the Enlightenment, so who better than me to audit it while I’m in there?

Here’s an excerpt from my romantic Fidelio composition:

FIDELIO ACT 2 (FLORESTAN’S ARIA)

Freedom loves a good dungeon.

The free leave offerings to the spirits of those cast out

to the dark places,

the deep places

that lend boundaries of gratitude

in the form of cautionary tales.The tighter they are chained

in their lust and loathing

of these fallen others,

the closer they are to liberty.Their walls are safe,

their walls keep them from their terrifying biology,

and they are clean and enlightened

and charted.Their walls are the sails of a ship,

filled with muses for the inmates of this dungeon of the earth,

this global south

where they make cultural embassy.But ocean and sky spin otherwise here,

a cultural Coriolis effect gripping this ark

of northern lights in a

whirlpool of dysphoria. The

siren call ringing out from these pristine decks

falls on savage ears

like a death wail,

and sailors plug their ears with wax

to avoid hearing the song sung backwards from this place.O brave sailors and dungeon masters,

to descend to the depths of these mines,

(to do what must be done in service of the light!)

O bereft outlaws and wretched scapegoats,

to endure what must be endured to make freedom free!Muses write love letters to the convicts here,

and sometimes they write back.Mostly they don’t, and those forlorn castaways carve unique tokens of love

as they die on the shores of memory.The free weep at their plight,

because they know the dungeon is needed.Not very romantic, I know. You try and do better when you and your woman are locked down in a tight space for two years with nothing to do but work, change nappies and tear pieces off each other’s souls.

I keep getting in trouble for referring to my spouse as ‘my woman’. That’s who she is to me—wanch ngatharam, and I’m pam nungantam, her man. Apparently that bit of palaeo-misogyny loses something in translation for the metro middle-class people I’m attempting to mingle with lately, so I’ve had to alter my language and start saying ‘my spouse’. The problem lies in the cultural baggage that comes with the possessive form in English grammar, and with the language of property law.

In our Aboriginal communities, when people first meet you they will often ask, ‘Who own you?’ This doesn’t signify a property relation—it is all about what groups, pairs and lands you belong to in your relationships, which are governed collectively. Belonging and ownership means something completely different from possession in our world. It means being in relation to family and community and place. Your belongings are not your property, but your connections. This worldview is not very compatible with the political economies, legal systems and marketplaces we must interact with to survive.

In the Melbourne suburb where I’m staying, houses routinely sell for over a million, because you can’t even have a humble two-bedroom shack anymore unless you’re a millionaire. At a recent property auction, the seller felt a bit strange about inheriting this capital passed down in her family from the early days of the settlement, capital she had not earnt. She hired a local Aboriginal Elder to come in and do a smoking ceremony and Welcome to Country ritual. I guess the smoke was to cleanse the blood off the land and settle the spirits, and the welcoming ritual was to invite the new owners in to possess the land. The seller also performed an Acknowledgment of Country—basically a nice way of saying, ‘I know this is your land and I’m sorry, but I’m occupying it now and I’m not sharing. Ever.’

My generation was the first in our community not to have our wages quarantined by the state government permanently, never to be returned but to be spent on infrastructure: the roads and electricity poles and bridges connecting all these land enclosures that our betters would pass on to their children and grandchildren in perpetuity. We don’t inherit any capital. Two-thirds of the world’s capital is land, and this is used to leverage debt through mortgages. The mortgage was once a novel tool that was used to trick First Peoples into signing away their reserves legally. Now the real-estate bubble is so huge that there is little chance of buying a basic shelter, let alone the land beneath it.

This is how it happens. Power tries out terrible things on Indigenous populations first, but you have to know that the same things are eventually coming for everybody else. The Ponzi scheme of global finance is teetering a little now, and things are getting a bit tight. One of the best things about reading history is seeing every single civilisation ever doing exactly the same thing with their housing markets, then collapsing into a big pile of hot sand. It’s like watching the film Titanic over and over—you know what will happen every time but it’s still exciting.

All I can see in the future of property law is unstoppable entropy in the landscape, territories that will certainly never be surrendered in any rebooted Enlightenment. All land is divided into parcels that are enclosed by boundaries signal-ling ownership by states or individuals. The Enlightenment gives us, theoretically, the gift of equal participation in a game of musical chairs in which we might seize one of those parcels of dirt and use it to secure our survival. But the enclosure of the land in this way means that the land must die.

The free movement of human and non-human agents (including animals, winds, waters and plants) is inhibited, and the exchange of energy and information (spirit) is stifled across entire bioregions. Humans as a custodial species are denied access to this land to care for it. This is because an asset can only be priced if it is limitable and excludable, so access must be limited by barriers that are enforced with the threat of violence. The choice of who is granted access to land is determined by a caste system that is organised by laws—zoning and other laws—that create structural inequality. This is the actual reason for marginal groups being imprisoned and killed, by the way—it’s not all down to the old-school discourse that comes out after your racist uncle’s third beer.

This caste system is essential for a growth-based economic system to function, since an economy cannot grow unless demand exceeds supply, meaning there must always be more people needing goods and services than are available. This is called the Economic Problem. It requires that laws uphold a social caste system that makes commodities and capital limitable and excludable to ever-increasing numbers of people in the lower castes. Unfortunately, increasing demand in this way also ramps up inflation when there is plenty of cash around—another mechanism for transferring wealth from the lower castes into the hands of elite hoarders. In this way, a system of enclosures inhibiting the regenerative processes of the landscape must be upheld in order for the economy to function. It’s a pyramid scheme requiring periodic resets, so every now and then you need to goad the lower castes into a revolution to help reboot the system.

This system requires inequality and exponential extraction of resources and energy from land and communities. It also needs to outsource the entropy (conflict, waste, depletion) of the extractive system to zones occupied by people from the lower castes, as well as non-humans (rivers, species, climates, soils). These damaged ones are referred to as externalities.

The Enlightenment that produced this system also promises freedom from its destructive effects in the pursuit of equality, liberty, truth and other lofty ideals. It is possible that there is some truth to this claim. I’m not a fan of throwing babies out with bathwater so I have worked hard to connect respectfully with the people who own all that water and are, likewise, working hard to protect their stake in it. I have very close relationships in the vast collective of interest groups that make up the Enlightenment preservation community. They’re good sports who enjoy my cheeky engagement with their ideas.

I’d like to share these community relations with you, in a fun way. We’re laughing about ourselves as humans together, which is a wonderful foundation for having a yarn, given that the last few paragraphs got a bit dark and complicated, and too much of that stuff interferes with your cognitive function.

The Enlightenment 2.0 crowd sits within a hell of an algorithmic ecosystem, encompassing the complexity science community, the blockchain/crypto community, the tech-bro community, the psychedelics community, the Californian ideology community (which is a confusing combo of meditation/psychedelic enthusiasts and eugenics/free-marketeer types), the sense-making community, the heterodox thinking community, the coaching/leadership community, the meditation/eastern spirituality community, the decentralised finance community and the intentional community community. They are a mixed bag of neo-cons, libertarians, centrists, classical liberals, crypto-fascists and greenies. And my algorithm in the online universe currently lands my thinking right in the middle of it all, because these thinkers seek palaeolithic precedents to support their claims as being derived from the ‘natural order’.

Most of these communities are full of interesting thinkers and good people, although there are a few grifters who understand where they are in the algorithmic jungle and how to whistle in the dogs for clicks. The rest are often used as a gateway drug for redirecting vulnerable users deeper into the dark alleys of disinformation. If you’re adjacent to any of these communities in your subject matter, the algorithm will often send you a very specific kind of consumer, one who is only a few more automated recommendations away from writing a manifesto and buying a rifle.

I’ve spent a lot of time exploring that world, mostly with thinkers from the US and Europe. My Elders tell me I need to take a break from the American ones particularly, because I’m becoming addicted to their exhilarating ways and they are making me sick in my spirit. So it’s a relief when I get to talk to thinkers from my own hemisphere from time to time. Americans are exciting and fun and make me feel great, but sometimes they scare the shit out of me.

I’ve been yarning with the maverick Australian economist Nicholas Gruen for over a year now. I once described him as a ‘white Kant philosopher’ which he thought was hilarious (and it is, but only with an Australian accent). When we first met he told me my thinking was all a bunch of party tricks, then put me through some intense Socratic drilling to help me sort out my reasoning. He’s still trying to hone my logic, although he’s been unable to shake complexity theory loose from my toolbox yet. He says it’s a fad and a grift. I love talking to him and revel in his elegantly brutal critiques.

He’s always said he’d never read my work because he doesn’t like pop science, so when he called me today because he’s been reading my book Sand Talk, and he wanted to accuse me of sniffing around Rousseau a bit too much, I was pretty damn thrilled. Too much luck to be writing a chapter on the Enlightenment and capital, then get a call from Gruen out of the blue. He describes himself to me as ‘a liberal unhappy with the Enlightenment’ so he’s perfect for this yarn. Inside dirt from an Enlightenment whistleblower! Let’s go!

Nicholas is a classic progressive liberal, which lands him right of centre in some contexts. If you find yourself involuntarily placed in that spot on the political compass, you tend to do far more debating than yarning, and regularly employ crude rhetorical devices like, ‘What’s your plan? What’s your plan? I’ll tell you my plan!’ There are some standardised talking points you might revisit fairly regularly, like ‘universities are broken’, ‘cancel culture is out of control’ and ‘publishers limit free speech’. Also: ‘what would Dr Martin Luther King Jr make of all this?’

In his critique of the Enlightenment he draws upon a golden age of female philosophy at Oxford. While men were away at war, female scholars expanded the discipline of virtue ethics, which challenged the Enlightenment notion that science can get to the truth of all things. While the scientific method has unlimited potential to explain the universe, it is limited in what it can tell us about ourselves. He says the project of defining and shaping human social relations and collective meaning based solely on science has had catastrophic results.

He tells me modernity was born in blood. That we have been eaten by the machine of this system and are now living a pseudo-life. Recalling the Luddites sabotaging the machinery of the industrial revolution, he asserts that they were not against the technology itself, but the way people were pushed violently or starved and harassed into industrial labour systems. ‘When we industrialised labour we industrialised oppression.’ The birth of liberty was compromised—the American and French revolutions contained sublime ideas of liberation, but these co-existed a little too easily with the industrialisation of slavery. The racialisation of slavery. ‘And that’s the fragmented world we’re in.’

But I want him to show me the good parts of the Enlightenment that I can keep on this yarran-wood boomerang, so I need to hear some arguments in defence of it. I offer a provocation. ‘Tell me one great man from the Age of Reason to modernity who wasn’t a bit of a dog.’ He can’t think of one off the top of his head.

He does declare that he is a lover of the Parthenon, cathedrals, Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man, and critique and dissent for improving society, all of which he finds to be sublime Enlightenment aspirations he’s not inclined to apologise for. ‘But people make associations with those things that I don’t want to associate with them. I’m for western culture.’ He says one of the highest aspirations of the west is dissent, a product of the Reformation, following the Thirty Years War which killed perhaps a quarter of the people in Europe. The story goes that the warring factions called ‘parley’ and decided to implement listening and tolerance to stop the slaughter, and that these ideals then became foundational to European culture forever after. Tolerance of dissent can become odious for some however, when it is used to assault the foundations of reason that invented this tolerance in the first place! And so we loop back to ‘cancel culture’ and disinformation.

I argue that cancel culture and disinformation are twin moral panics that are engineered and not particularly new, being products of the Enlightenment. Some of the earliest pamphlets off the printing press declared, ‘Catherine the Great is having sex with horses!’ (translation: cancel this woman before she destroys the feudal system) or ‘The Jews have a plan to take over the world!’ (translation: give the people someone to cancel who is not an oligarch). I also point out that in its current permutation, the phenomenon of ‘being cancelled’ was initially called ‘being Dixie Chicked’ after that band was silly enough in 2003 to speak out against the invasion of Iraq. By the time they finally got their careers back on track, however, parts of the left had also begun deploying the same technique, and the Chicks were cancelled again for being Southern and whiter than a catfish belly.

But we could argue around all those pointless points forever. That’s not what this book is about.

So, with Enlightenment protocols such as tolerance, utility and respectful listening firmly in place, Nicholas and I paddle our canoe on against the current, seeking ‘common sense’ in dialogue and good relation. From that frame, culture wars appear to have little utility at all. To me they always seem to be about power plays, to propagate wrong stories under the cover of dust kicked up by a mob of emus fighting over shiny fragments of material culture and moral high ground. So they’re useful for some people, I suppose.

The twin projects afoot right now are rebooting the Enlightenment and rebooting capitalism. This is a rebranding of Reason as inclusive, and free markets as fair and distributed, while the world burns. The argument goes something like, ‘Sure, change the world with stakeholder capitalism, finance with feels, but just as long as we can hold on to our capital. And sure, bring social justice to the disciplines, but just as long as we can keep our controlling stake in the cultural capital.’ When you take away all the self-interest and culture-war rhetoric, though, what is left of the Enlightenment that is truly worth keeping?

To discover that, we need to steer the canoe into deeper waters, and yarn about the rivalrous dynamics inherent in the code of the Enlightenment. I begin clumsily, tentatively narrating some naive ideas about dialectics, of synthesis arising from opposing forces in western governance, which Nicholas swats away like flies.

He calls this a ‘vulgar Marxist interpretation’ of Hegel and dialectics, offering instead a more nuanced understanding by drawing attention to the first line of my Fidelio piece: ‘Freedom loves a good dungeon’. There: the dialectic dance in a nutshell. He says the real message of Hegel is closer to my idea of Indigenous opposites existing as dyads rather than binaries—they’re usually two sides of the same coin rather than two ends of a spectrum. Aboriginal people don’t have to choose between the individual and the collective, left and right, because we are both at once. We are unique individuals with no boss, bound in dense and complex systems of relational obligation. This same philosophy is certainly present in Enlightenment values, here and there. Nicholas thinks it’s a shame that it didn’t end up informing the governance systems that emerged from the period.

He brings up the emu story I shared with him, which I framed as a cautionary tale about narcissism. He wryly reflects on representative democracy as a selection operator for ensuring that the worst people are always in power. ‘Wasn’t it clever of us in the eighteenth century to set up a political system based on finding the narcissists and promoting them to the top?’

I suggest that this was a result of flawed reasoning in the Rights of Man workshop that happened after the French revolution. According to the story I heard, they got stuck on the ‘Jewish Question’ and argued about whether that community could have rights or not. Eventually they decided that Jewish individuals could have rights, but their community could not. This little exclusionary bug was later extended to every marginal community and was possibly the reason individualism and collectivism ended up at either end of a political continuum rather than continuing to be two sides of the same coin. Bigotry is a bastard. It’s not my political identity or victim status that causes me to dislike it, though—I hate anything that’s based on logical fallacy and makes systems dysfunctional.

Nicholas says there’s still a mechanism or two left in the Magna Carta that remain unsullied by rivalrous dynamics and skewed logic. He includes this document in our yarn because it inspired a lot of the ideas in the Enlightenment. One of them is the jury system, which he proposes as a better model for representative democracy: leaders would be selected from a pool like jurors and rule collectively. He says this would work, because juries tend to suppress narcissists. This sounds reasonable, but I can’t seem to get 12 Angry Men and the OJ Simpson trial out of my head. He tacks back to my thoughts on perverse incentive systems and competitive dynamics and says something that turns my thinking on its head. ‘Any system of incentives taken to its logical extreme will poison you.’ He cites Gresham’s Law (by way of Copernicus), that bad money always drives out good. And there’s always bad money.

We decide to paddle further into a thought experiment drawn from Nicholas’ study of virtue ethics. He introduces the philosopher Alasdair Macintyre’s provocative scenario of a world in which there has been a pogrom against science, complete with rioting, book burnings, lab demolitions and executions. Science has been banned from education for decades, until a new regime decides to restore it. The question is: what would the new scientists have to work with but fragments and partial hypotheses, charred segments of articles, hazy memories and damaged equipment with functions that are unknown?

I feel triggered as hell about the parallels between this scenario and my own community’s efforts to recover critically endangered cultural knowledge and languages lost during Enlightenment-fuelled genocides. But this yarn is important to me. I’ll find a culturally safe space to weep into later, if such a thing exists.

We both reach the same conclusion that the ‘science’ they would be recovering in this scenario would be cobbled together with bogus narratives and unifying theories, unproven laws and competing equations with no interoperability. Factions would emerge with no way to resolve their differences and the public would fight for their preferred version of ‘the science’ in the streets—all of which sounds to me like a lot of the science we have right now. Nicholas takes this observation a step further and says it is also a perfect description of the pseudoscience of economics, which is an amazing thing to hear coming out of an economist’s mouth.

Nicholas talks about social-justice warfare as another discipline analogous to our scenario. He talks about how horrible Twitter is and how annoying ideas like ‘micro-aggression’ are. I say every tweet is a micro-aggression, and he likes that idea so much that he tweets it immediately.

I tell him that the headlong rush towards premature certainty in our thought experiment scenario is present in many disciplines and institutions today, as a direct result of flawed operating protocols in the Enlightenment. Nicholas never lets me get away with making claims like that without giving an example as evidence, so I talk about finance.

I say that Age of Reason patronage as an elite philanthropic incentive system for sustainable innovation was flawed as hell. It makes today’s peer review and human research ethics processes feel like a soothing massage. Some chubby prince tells me I can’t have dancing in my opera because it’s sinful, and then forces me to tutor his tone-deaf niece on the harpsichord—no, thank you! Then there’s all the jealous Salieri syndrome sufferers (a condition named after Mozart’s nemesis) competing for favour and funding by undermining your work and reputation. It’s still going strong today in pretty much every discipline.

Nicholas isn’t biting. I throw out a sexy provocation about Enlightenment metrics measuring nouns rather than measuring verbs like Native Americans do, and he calls me out on my Ted-Talkification of thought. I don’t even have visuals to fall back on in this yarn, because I know he’s sick to death of policy-framework diagrams and probably never wants to see another shape communicating an abstract idea again. He once described a diagram to me that was a circle with ‘Centring Indigenous voices’ placed way outside the circumference. He muttered, ‘It wouldn’t have even mattered if it was in the middle. It’s just a fucking diagram.’ I love this guy.

He suggests that the worst parts of social-justice warfare come from the worst parts of the Enlightenment. He doesn’t like the fact that there must be rules and protocols for discourse, which is fine in the courtroom but frustrating in public speech.

He is also annoyed about all the clickbait article titles these days, which entice people to form opinions without reading beyond the headline. I think that’s also something that started in the Age of Reason. Look at what they did with Darwin’s work: Survival of the Fittest? Very well, let’s break up all these communities and put the unfit populations in their place! They’re going to die anyway!

He says he’s more vulnerable to attack than I am because he’s an old white guy. I say old white guys need to work on their resilience and stop catastrophising over a bit of pushback that’s frankly not half as bad as what other thinkers for over a century have had to endure and still have to go through on the daily. He says that can’t be right because I’m selling way more books than he is. I say it’s not my weak-tea cultural identity selling books—there are plenty more authentic, marginalised authors who are far better writers than I am, and they’re struggling to get noticed. So identity is certainly not what’s selling books here.

He suggests it’s probably because I’m doing something similar to Jordan Peterson, which he describes as ‘taking a core of truth and building a bullshit hypothesis around it’. Well played sir. He says I do it heaps better than Jordan, though, and I suddenly feel the urge to write a bit about lobsters. (Or maybe echidnas—I could insert it as the first paragraph in this book.)

In the end, we agree that satisfied readers are mostly just relieved to find a yarning place where we can laugh at ourselves and each other together while casually kicking ideas around and sharing our stories. If there is an Enlightenment 2.0, please let it have some jokes in it. Keep the tolerance of dissent part, and then leave heaps more open to local reinterpretation and elaboration, much like the fluid monologues in Fidelio. And we need to rethink our understanding of belongings. There is enough left there for my Enlightenment boomerang to emerge, even if it has gone from a massive weapon to a tiny toy that comes back when you throw it away. I don’t want to throw it, though, because it doesn’t fit my hand. It was carved with a logic that is alien to me, resulting in story that feels accurate and reasonable, but somehow wrong.

I’m sending the boomerang to my friend Jamie Wheal in the US, a peak performance expert who says that the French Enlightenment and extension of equality for all people as inalienable human rights was ‘shitty execution’ and even ‘wrapped in a pile of steaming poop’, but potentially a beautiful thing that could lead us all to a shared global humanity. He will make better use of that boomerang than I could.

I have been too hasty cutting two large pieces from the yarran wood. Those were Nicholas’ Enlightenment ideals about juries extinguishing narcissists, and the abolition of the Divine Right of Kings. Those were good ideals, but I just couldn’t see them existing in the current system. I’ll keep those pieces, though, and turn them into message sticks to pass on to my favourite rogue economist.

Nicholas has a good joke, but it’s from a Woody Allen movie and I ask him if he’s sure he wants to proceed with platforming an alleged monster. He does, so let’s hear it before we push our canoe into the river and start our journey into the first circle of hell.

So, a guy goes to see a psychiatrist and says, ‘It’s not about me doc, it’s my brother. He thinks he’s a chicken.’ Psychiatrist says, ‘Why don’t you have him committed?’ And the guy says, ‘I would, but we need the eggs.’

Anyway, the Enlightenment is a bit like that.

Dear NIcholas; Another good selection, that I read with interest and mostly pleasure. Good to read papers or watch vidoes on topics that challenge my current perspective. At 76 I find my perspective swiveling on many topics, often to end close to the subtitle of your blog - 'I know nothing', but still I care.