This piece began as a lengthy comment responding to Ken Parish’s post on my proposal for a third ‘people’s chamber’ chosen by lottery.

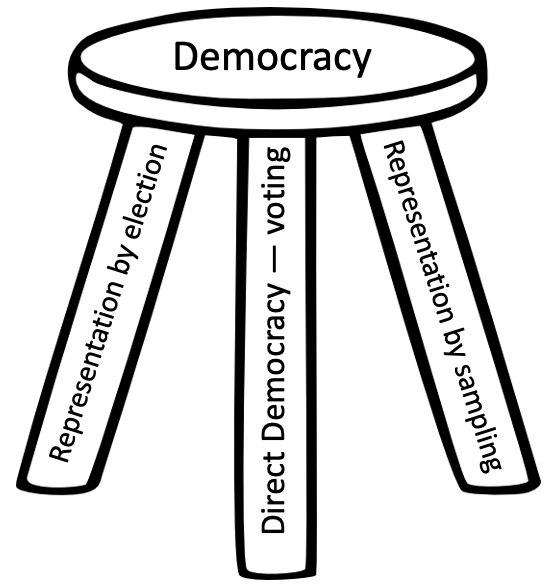

I don’t support citizens’ juries as some kind of ‘hack’ to the existing system, which I see as in an advanced state of decay. That’s because, in the West in the last 800 odd years, there have been two different ‘logics’ applied to the democratisation of monarchy. The first was Magna Carta and the idea of entangling the judgement of one’s peers into the processes of government. And the second was the idea of applying ‘checks and balances’ to government from the 17th century on.

In the former case, an institution was (eventually) developed that husbanded the life world of the people within the machinery of government. In the latter case, the idea of checks and balances was a fine one. But the entire system was administered by the same elite class that it was supposed to hold to account. And that’s turning into an unaccountability machine (see Robodebt, the NACC and the rising tide of careerism in public life to say nothing of the unaccountability machine in the wider governmental structures in business).

In government these checks and balances are mostly, comically easy to subvert – you just win government and appoint your cronies. We’re seeing this in the US and they have more checks and balances than us – like Senate confirmation hearings. Once the partisanship reaches a certain level, things can move very fast.

We might have democratised monarchies by doing something similar to Magna Carta in the legislative and executive branches. But it’s a simple fact of history that we didn’t. But we can get glimpses of what that might look like by looking around. Belgium now has parliamentary committees with 15 elected legislators and 45 randomly selected citizens. There are standing citizen councils in East Belgium, Paris and a few other places.

Michigan has the Independent Citizens’ Redistricting Commission, which draws electoral boundaries. And it does it in a way that is much less corruptible than almost all the systems used elsewhere, including here. These are the kinds of institutions we should be developing. Elsewhere in the Western world, these kinds of things are easily subverted by doing what Scott Morrison did with the AAT. Appointing your cronies to ‘independent’ positions.

If that’s the ‘bulwark against tyranny’ argument, there’s also the ‘can we please have a sensible conversation’ argument. Even where there’s a strong cross-bench, MPs can’t remain MPs without a good deal of double talk. I was discussing budget repair with an independent member of the Tasmanian parliament the other day and they’re almost as hamstrung as party politicians. Because if you want to get elected, your ‘messaging’ though our marvellously dystopian mass and social media has to be pretty reductive. You have to spin your question begging nonsense for media management reasons. Taxes are bad and spending is good! And we wonder why fiscal responsibility is a growing problem!

You might ask why don’t I want to abolish the existing system and just back sortition based citizen assemblies.

Two reasons

No-one would care. So having convinced myself that sortition would make a major improvement to our system, I’ve tried to work out what kind of pathway of activism might help promote its presence outside our judicial branch.

I don’t have a blueprint. I have only the old 18th century basic idea of checks and balances together with an attempt to implement them properly. A new DNA which can infect the host as it has the law courts.

Finally, before getting to some specific concerns, it’s important to stress that all human institutions, like humans themselves have profound flaws. And in all this the growing dysfunction of the existing system looms large for me. What I’m proposing is extremely low risk and I think it could be highly beneficial. But it’s like shooting fish in a barrel to point to shortcomings. The question is how those shortcomings stack up against the shortcomings of the system we have now and how the changes I’m proposing could address the shortcomings of the existing system.

Some responses to specific concerns:

How can citizens’ juries be representative if people will opt out of them?

On the representativeness of the group, I think that, at least as they are getting established, we shouldn’t require people to leave their job to serve (this also has attractions for me because it reduces the cost of philanthropic funding). For illustrative purposes, a term in the chamber could begin with the person committing, say, two full weekends in the first month for face-to-face meetings and one two-hour teleconference a week during the week. Then they might be asked to spend around one weekend day a month plus the same weekly teleconference load throughout their term. Jurors would be paid ideally at the same rate as parliamentarians for their time.

While I think this would substantially increase the take-up rate itself, I think it would increase substantially over time because, when they’re competently run, the participants report an immense buzz from them. About 95% of participants describe them as good, more than half of those describe it as very good, with about half of those experiencing a kind of epiphany and then some share of those actually changing their lives as a result – standing for local council or doing some other kind of public service at the next opportunity.

Given the public unfamiliarity with these processes – and elite suspicion of them – you need to expose people to them. You need to show them for people to understand what they are. I participated in Rory Stewart’s campaign to be London Mayor. He was promising a citizen council, but it ‘focus-grouped’ badly because voters thought it was ‘another committee’, another politician’s gimmick to appear to do something without doing anything. Instead of another committee, they wanted “a strong leader”! (I wonder if Rory’s ratings would have risen if he’d died his hair orange? Nobody ever talks about it.)

Won’t citizens’ juries harbour the same kind of factionalism as parliaments?

Jay Weatherall will tell you that the assembly shouldn’t be too large because about 5 percent of the population are natural factionalists, and they provide the seed for larger factions – as they did in his 340 person citizens’ jury on nuclear waste (though there were also problems with the way the public service ran it - giving jurors the impression that the organisers were trying to influence their decision). But obviously the point is to some extent valid.

But as I’ve seen more I’ve understood how often we judge people’s behaviour by what is familiar to us now. Individual citizen jurors attend their first meeting thinking the same way. They expect aggression, spin and point scoring. But then they experience a shock of recognition—an ‘aha’ moment. They look around and find people like them and their next-door neighbour. Many of them exit these processes without having come to agree with those with different views, and yet they’ve come to respect them – with immense relief as it rekindles their faith that democracy really does make sense, even if the freak show they see on their screens doesn’t.

What you’re witnessing in contemporary politics is a system which has been optimised for a couple of centuries now, a system of cheap talk and ‘messaging’ in which, as I argued here, a cultural version of Gresham’s Law has been eating its way through our public life so that today the principle purpose of virtually every public utterance whether in politics, business, or media is the advancement of the interests of the speaker and the manipulation of their audience.

One of the main reasons I believe in citizens’ juries is that the life world has been more or less extinguished in our public life by competitive shoggoths (capitalism, electoral democracy, social media and AI) which drive out non-instrumental values and behaviours. And, I think the life-world of ordinary interaction with others in families, workplaces, schools and so on is the world in which we gain our bearings – our grounding with reality. Juries provide institutions for husbanding it back into public life.

It’s why I so love this story from Utopia.

It captures the relentless progress of the bullshit world in displacing the lifeworld which is the ultimate anchor of our lives, our sanity and our decency. As Alasdair MacIntyre put it in After Virtue:

In any society which recognized only external goods, competitiveness would be the dominant and even exclusive feature… We should therefore expect that, if in a particular society the pursuit of external goods were to become dominant, the concept of the virtues might suffer first attrition and then perhaps something near total effacement, although simulacra might abound.

Won’t a growing parliamentary cross bench sort things out?

I too thought the Gillard Government showed the virtues of a hung parliament. But that was Julia Gillard’s metier. How would our other political leaders have gone in such a circumstance? (Hawke is the only one I’m confident about.) Hung parliaments can lead to better or worse government and I don’t think we should be too confident of which direction that will go. They can also easily lead to weak governments that forever teeter on the brink of dissolution, as they have, say, in Italy. It depends on the maturity of the political culture. (Right now, the question of whether it leads to better or worse government is in play in the only state with proportional representation in the lower house – Tassie. So far it’s been a counterexample to Gillard. We’ll have to see what happens with the new government. Let’s see how fiscally responsible it is.)

I’m also not sure how robust the cross-bench is in single-member electorates. Certain important features of Australian elections help – compulsory and preferential voting. But there remains huge inertia towards the major parties and their way of doing politics. You need a hell of a lot of money and professional support to campaign, and the the Lib/Lab duopoly is trying to get an unfair advantage over independents (something that seems both shameful and foolhardy for the ALP to participate in, but what would I know?)

Remember what happened to Tony Windsor and Rob Oakeshott. They lost their seats once they stopped campaigning in poetry and started governing in prose. Likewise the Australian Democrats and the Lib Dems in the UK. Yes a cross bench can survive as a protest. I’m hoping the community independents will do better. But it’s a great deal of work and the major parties have a lot of options to run you out of town.

Nicholas, this is a brilliant and necessary piece. I have little to give in critical opinion on the specifics, but I do have a question to ask in the context of the historical moment you describe.

I want to consider that while we can and should debate system design, any system must be constructed to operate within the substrate available to it. In the language of Constructor Theory, it is constrained by the possible tasks its design can perform upon that substrate.

The problem with modern democracy, I believe, is not a flaw in the system's design per se, but a fundamental degradation of the substrate upon which it operates. The system places power with citizens to come to accord on the visible issues of the day, but it presumes a "common interest" that no longer naturally exists. This "informational malaise" among a diverse and disconnected citizenry creates a logical vacancy at the heart of the system.

This vacancy gives rise to the need for a manufactured and elevated "common interest" within political parties. The work of politics is no longer about governing, but about the complex and expensive business of generating interest itself. This business is expensive, so parties inevitably turn to wealthy elites, severing the feedback loop from common voters that is supposed to connect them to the people.

Your proposal for a people's chamber is a powerful attempt to patch this system, but I wonder if we first need to discover and prop up the logical gap in the substrate itself. Where can we find the common ground?

Is it bio-logical? Are there real, common interests in matters of poverty, healthcare, or other matters of the body?

Is it eco-logical? Is the environment, natural or built, a matter for everyone's national concern?

Is it intra-logical? Are there common issues of regional disparity?

Is it inter-logical? Is there a common interest in our nation's sovereignty and its relationship with the world?

Is it psycho-logical? Is the very nature of the Australian project sculpting our citizens in a way that needs common debate?

Is it socio-logical? Is there a shared cultural emergence that requires a common set of policy options?

My wager is that while all these "logics" are ruffled through in every election, the actual selection pressure is based on a much cruder table of options. For each party, the column titles are the same: Us, Them, Cash Cows, and Sheeple. The qualifier is "screws," and the winning formula is the one that maximizes how much good it does for "Us," how much bad it does to "Them," how tightly it can turn the screws on "Cash Cows" for funding, and how effectively it can screw the "Sheeple" into voting for it.

This connects to a thought I recently published in an article, "The Purpose of Vision is to Become Blind." The primary benefit of our senses is to allow us to become consciously ignorant of almost everything they perceive. We operate 99.99% of the time as zombies, mindlessly avoiding obstacles, to free up our conscious awareness for what is truly meaningful.

The current political system violates this fundamental principle. It is a system of disingenuous "screw tactics" designed to hijack our better judgment. People disengage not out of apathy, but as a healthy, protective act. They instinctively want to remain "blind" to a system that is designed to be a meaningless obstacle, not a useful tool.

This, I believe, reveals the true debate that is missing from our commons. The missing area where democracy requires its own renaissance is not technological; it is info-logical. If we are to design a better system, we must also focus on constructing and maintaining a coherent info-logical commons. This would be a shared informational substrate where genuine, non-manufactured common interests can actually emerge and be acted upon within the dynamics of a revitalized democratic system.

You may say, "Where might we find such a devilishly ingenious info-logical commons?"

Well, to this I'd take a line from Black Adder's Baldrick and say, "I have a cunning plan."

I greatly admire your dogged - and it seems to me intelligent and wise - pursuit of this admirable goal. Bravo.