Democracy: doing it for ourselves

Next Wednesday I’m off for my first overseas trip since COVID darkened our doorsteps. First stop is the remarkable Kilkenomics in Ireland and then it’s on to the UK. The highlight of my trip there will be a presentation at NESTA.

Please come if you can. (Fly from Australia to London if necessary — That’s what I’m doing.)

On 15 November, we’ll be joined by Nicholas Gruen, CEO of Lateral Economics and visiting Professor at King’s College London, and a panel of thought leaders.

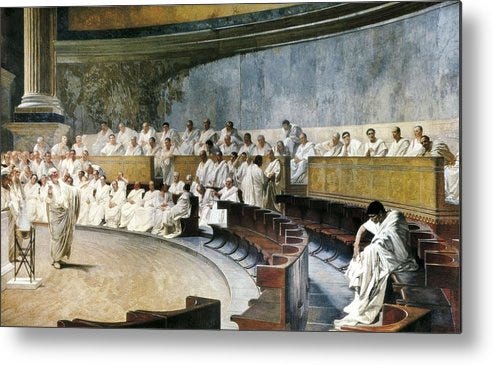

Gruen will argue that citizens’ juries will remain marginal if they remain one-off events commissioned by, and then reporting back to governments. He will present the case for a standing citizens’ assembly to operate as a house of parliament.

Rather than waiting for the government to accept this, an assembly can be privately funded, via philanthropy and crowdfunding. As it sits, it will showcase the transformative potential of this other, far more representative and constructive way to represent the people.

Nicholas will be joined by

Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator at The Financial Times – whose recent column explored these possibilities;

Claire Mellier, co-founder of the Global Assembly for COP26 and knowledge and practice lead at Iswe foundation.

Ravi Gurumurthy, NESTA CEO will chair the event and draw on insights on Nesta’s recent work in this area.

This free evening event will be held in person in central London. You’ll hear live from our panel of experts, followed by an audience discussion and a networking reception. Can’t make it in person? The event will also be streamed online.

Rory Stewart: enjoying being in Alan Partridge’s company

And in the spot above Theresa May!

Sortition and serendipity

A famous story of reconciliation — between a ‘red-neck’ and a gay man during the Irish citizen assembly on same sex marriage. Thanks to Sonia of the Sortition Foundation for bringing it to my attention. It’s a fine story, but rather padded out in the tradition of padded out ‘long-form’ journalism. But worth a look, particularly on Finbarr’s background and the abuse that made him so homophobic. It’s a fine illustration of G.K. Chesterton’s dictum that “All real democracy is an attempt ... to bring the shy people out.”

The participants at the table introduced themselves one by one. When it was Chris’s turn, he was so insecure that he hardly knew what to say. So he said what he was thinking: that he felt out of place. That he would probably not have the confidence to stay. On the other side of the table, Finbarr started to nod.

Seeing that his words were resonating with Finbarr, Chris kept talking, saying that he didn’t know why he was here, among all these important people. Finbarr was now agreeing so emphatically that Chris thought he might climb right across the table.

Then Finbarr burst out: “Thank you for saying that. That’s how I feel.”

At lunch, Finbarr and Chris sat next to each other, and during dinner they shared a laugh about all the experts with their complicated formulas and numbers and graphs who had taken the stage that day. When, at some point, the moderator had asked whether everyone was able to understand the presentation, Finbarr’s hand went up, and he said no, that now he understood even less than before. Chris had been glad, because in truth, he had been just as lost.

In the evening they met at the bar for a pint. Finbarr’s fear hadn’t quite disappeared, but he was surprised by the discrepancy between Chris’s appearance, which conformed exactly to Finbarr’s expectations, and his straightforward manner, so similar to his own.

Vale: Max Corden

In a lecture he gave last year, Ross Garnaut spoke of the six economists who made most impact on him when he arrived at ANU. Three were Australians — Nugget Coombs, Trevor Swan and John Crawford. And three were ‘continentals’ as they were called in the 1950s (and in the lovely novel and film Women in Black — which became Ladies in Black in Bruce Beresford’s film and Tim Finn’s musical of the same name — but I digress). Heinz Arndt, Fred Gruen (no relation) and Max Corden.

Anyway, Max was the youngest and one of the longest lived, but he died this week. My condolences to the Corden family. I wrote to Simon Corden, Max’s nephew that I was going to be in a plane to the UK when the service for Max is being held. But I will be catching up with Martin Wolf and we shall toast Max. My tribute to Max on launching his memoirs is here.

Martin sent an email to his many friends who knew Max and attached the forward he wrote for Max’s memoirs with this note. “No writing I have done has meant more to me than this piece”. He gave me permission to reproduce it below.

FOR MAX CORDEN

Max Corden – then, as he tells us, Werner Max Cohn – was born in Breslau in 1927 and moved to England in 1938. A lifelong Anglophile, he left for Australia with his family in 1939. There he was to become what he is today: Max Corden, Australia’s greatest living economist. This book tells his remarkable story.

I first met Max during his period teaching at Nuffield College, Oxford, between 1967 and 1976. I was a student at Nuffield between 1969 and 1971 and was one of those people lucky enough to learn international trade theory from Max, who was not only one of the world’s leading specialists, but was a superb teacher.

The characteristics of Max as a teacher are the same as those of Max as an author – indeed they are very much on display in this autobiography: the maximum of clarity with the minimum of unnecessary complexity. I consider of this lack of pretension as an Australian virtue. But it went with a commitment to ideas that is characteristically Jewish.

Max was far and away the best teacher and most lucid expositor I met during my time at Oxford. I think of those qualities as not just intellectual – though, of course, they are– but also as moral.

Max’s determination to get to the bottom of any problem he confronts and then explain how to think about it, rigorously and clearly, is the fruit of a profound diligence - an absolute refusal to be sloppy, confused or misleading. This diligence made him the remarkable teacher and analyst he is. And this, more than any particular bit of economics, was the most important lesson he imparted to me. He is an outstanding teacher and economist, because he is determined to perform his tasks to the very best of his abilities.

I drew two more lessons of great importance from Max. Since my background at Oxford had been in classics and then Politics, Philosophy and Economics, I lacked the mathematical skills that were increasingly in demand. As a result, I wondered whether I could find my own niche in economics. Max, who eschewed mathematics in his theoretical work, showed me that I could hope to do so. Economics, it was clear, had many houses. In one of them I could hope to thrive.

The second lesson was his ability to underline something I already believed. Economics was a political subject. Its proper aim was to make the world a better place. With his deep interest in practical questions, Max taught me that this was an altogether reasonable ambition. He also taught me something else: as he puts it in the book, “one’s choice of models must depend on circumstances”. Economics is not a religion; it is a toolbox.

At the time I met him, Max was in the middle of what was arguably his most intellectually creative period, when he did his seminal work on protection and trade policy. The interest in trade I learned from him has stayed with me ever since. His book, Trade Policy and Economic Welfare, published in 1974, shortly after I left Oxford is, I believe, his masterpiece. It has had a huge influence upon me and many others.

Subsequently, Max moved to work on problems of the international monetary system. In this area, too, his writings were marked by those characteristics of clarity and rigour. He sorted things out and so, when one read his work, one learned how to understand the issues, too.

In this fascinating book, Max tells of his entire life journey, starting with Breslau, the arrival of the Nazi in 1933 and his father’s imprisonment in Buchenwald, to the family’s very lucky escape to England and then Australia. He puzzles, rightly over the mystery of the demented and murderous anti-Semitism he managed to escape.

Max goes on to explain how he became who he is –an Australian and a great economist. Here, too, he enjoyed much luck. As is usually the case, great success requires the timely help of a number of kind and decent people. Max received this. And he repaid this help, over and again, to his country and the world.

In a sane world, Max would now be a celebrated German scholar. As it is, he was indeed lucky to survive the wreck of 20th century Europe. But his new country was lucky, too. By virtue of its far-sighted generosity, Australia gained an economist who contributed vastly to the domestic policy debate and added to his country’s global reputation. And I, as a result, gained my foremost teacher and a lifelong friend.

Looking for images of Max, I discovered that, like the economic historian Gregory Clark, he likes a good literary joke for a book title.

Israel and Gaza: where I’m coming from

A few people have inferred from things I’ve reproduced in this newsletter what my views are on the horrible things going on in Israel. I should clarify that my selecting them should not be taken as an endorsement of the views put. I am shamefully ignorant of the history and so of the rights and wrongs of the situation, though one source of my failure to learn more is that I doubt I’d be much more confident of my views.

There is one overriding deep sadness and concern. If you think about it, modern Zionism is a bit of a harebrained idea. Not necessarily a bad idea, but certainly an extraordinary one. It’s hardly surprising that, if anyone could do it, the Jews could. When I was a kid it looked like they were going to pull it off. But to do so they needed to get to a two state solution. Will the Arabs let them. I don’t know. But that’s the only safe harbour for Israel.

A couple of hundred years ago the West dispensed with formal discrimination of rank and entitlement and begun running everything through systems in which the power relations were reconstructed within systems which formally did not discriminate. The market does this and so does electoral democracy.

Fast forward two hundred years or so from the French and American revolutions (to around 1970) and within just a couple of decades Apartheid South Africa’s violations of this new norm meant that it simply ceased to be viable. There were lots of good arguments that it wasn’t so bad. Were black South Africans doing worse than neighbouring countries? Well not it seemed according to them — South Africa attracted black immigrants form other countries. Was black majority rule a good idea after Apartheid in South Africa. I certainly hope so, but it would not be too outrageous to say “too soon to tell”. And yet Apartheid South Africa became non-viable.

With a few basic demographic differences Australia would have gone in a similar direction. So the one thing that seems to offer some bedrock on which to begin thinking in the case of Israel is the non-viability of a one state solution — because it will be an Apartheid solution. In this regard morality is actually a menace. Because I think that — at least speaking not theoretically but by comparison with what else I know about other places — Australians are nice enough people. Really very decent. More so than many countries. But it’s not much credit to our morals that we didn’t end up in the horrors South did. Our demography saved us, not our decency.

I remember what a pinup boy Israel was when I was a kid. So smart. So strong. So much committed to modern liberal values — and a haven from the horrors — of the past. Always besting the Arabs who wouldn’t let it live. But also understanding that it needed to bring it all in for a landing somewhere that could endure. And, it seemed, fairly confident that that could be done.

It was a bit like my father thought of economic reform — as a natural expression of educated and liberal values — committed to the greater good through education, patience, wisdom, and decency. I.e. liberal in its original meaning — generous.

Well we know what happened with both of those things. Their commitment to human uplift somehow fell away — replaced by baser motives. And of course a vindication for those who always had a lower opinion of what we humans were capable of. They were at least right to this extent — they left us realising we’d lived through a golden age and now we’re falling to earth.

A two state solution seems virtually impossible today. And perhaps it is. But then I think Israel won’t survive and when it does get extinguished a once extraordinary experiment will have become dark and menacing. It will have lain waste to a people.

Two reasons to be more optimistic are

I don’t know very much and

History is always playing tricks on us.

On Certain Asymmetries

A few thoughts on how we talk about the Israel-Hamas war

If nothing else, the October attacks reminded the world why Israel takes such an aggressive, militarised posture towards its borders. That isn’t to excuse its myriad moral offences over the years. But let’s be clear about what and who they’re up against. Hamas and its allies are not interested in a peaceful settlement with the state of Israel. The only reason Hamas would agree to a ceasefire is to start planning for a new attack. Given that, what should Israel do in response to this one? You should not find this easy to answer.

The Israel-Hamas conflict is asymmetric in more ways than one. We are familiar with the asymmetric military and economic advantages that the Israelis have over the Palestinians, which is why the former are often - and sometimes with justification - portrayed as bullies. We tend to overlook the asymmetry of objectives. While the Israelis have shown themselves capable of treating the Palestinians appallingly, they are not seeking to annihilate them. The most fervent wish of Israel is to secure its borders and protect its people. If the Israelis let their guard down, however, they face being destroyed, by Hamas and its allies, to the last man, woman, and child.

There is also asymmetry in the protests on British soil. Israeli sympathisers have managed to protest peacefully without calling for anyone to be killed or chanting racist slogans - how about that. There has been a sudden and terrifyingly steep rise in anti-Semitic attacks in London, accompanied by a much smaller rise - thank goodness - in Islamophobic ones. Meanwhile, the Western left continues to act as if Israel is the only guilty party in the conflict. It’s as if they can’t process the horrors of October 7th - perpetrated by representatives of their ‘side’ - and so have simply pretended they didn’t happen.

Steve Coogan and Tilda Swinton were among two thousand artists who signed a letter condemning Israel’s actions in Gaza as war crimes, without specifying any (though the letter is right to condemn the use of the phrase “human animals” by an Israeli minister). Amazingly, and unforgivably, they somehow contrive not to even mention the October 7th atrocities, or indeed the actual and ongoing war crime of hostage-taking: over 200 Israelis are currently being held as human currency. I suppose the signatories just cannot compute anything horrific happening in the Middle East, and Israel not being to blame.

Similarly, over six hundred writers have signed a letter in the LRB which refers to the attacks only indirectly, in bland “both sides”pablum (many of those who in 2020 pointed to the inadequacy of “all lives matter” have retreated behind similar formulae). After that dutiful paragraph comes the letter’s most shameful sentence: “Nothing can retrieve what has already been lost.”

Netanyahu’s war

Netanyahu has been an ardent champion of West Bank settlements, the growth of which makes the idea of a viable Palestinian state fanciful. He has desisted from annexing (at least) large chunks of the occupied West Bank only because of likely US disapproval. UN figures show that in the ten years to 2022, the population of Israeli settlers in the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, grew to around 700,000. The settlers live illegally in 279 Israeli settlements across the West Bank, including fourteen settlements in East Jerusalem.

The company Netanyahu keeps should give considerable pause for thought. On 1 March this year the head of a pro-settler party, Netanyahu’s finance minister Bezalel Smotrich, called for the Palestinian West Bank village of Huwara to be “erased.” This followed a settler rampage through the village that one Israeli general described as a “pogrom.” A US State Department spokesperson described Smotrich’s comments as “irresponsible… repugnant [and] disgusting.” Undeterred, Smotrich followed up by declaring that “there is no such thing as the Palestinian people.”

Last August, Netanyahu’s far-right national security minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir, exhibited a similar sneering condescension, declaring that his family’s right to move around the West Bank “is more important than freedom of movement for the Arabs.”

Israelis mourning their dead might reflect on the awful reality that, stretching back to the 1980s, Israeli governments have provided limited funding and intelligence assistance to Hamas, at first seeing the Islamist organisation as a useful counterweight to the Palestinian Liberation Organisation under the quixotic Yasser Arafat. This assistance continued after the formation of the Palestinian Authority, Israel’s nominal partner in any “peace process.”

Michael Hirsh, a columnist for Foreign Policy, commented recently that Netanyahu’s various governments ended up weakening the Palestinian Authority president, Mahmoud Abbas — who wanted to negotiate — while strengthening Hamas, which has vowed Israel’s destruction. Hirsh quoted Gilead Sher, chief of staff to former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak, who has said that Netanyahu’s policy to “nearly topple” the Palestinian Authority fostered Hamas’s “sense of impunity and capability.” Avner Cohen, a former Israeli official who worked in Gaza for more than two decades, told the Wall Street Journal that “Hamas, to my great regret, is Israel’s creation.” …

In the New York Review of Books Fintan O’Toole wrote that “Hamas’s knowing provocation of Israel’s wrath against a Gazan population it cannot then defend shows that Hamas cares as little for its own civilians as it does for the enemy’s.” That is the sickening truth.

Ben Saul, head of international law at Sydney University, has argued that Hamas should be held accountable for its “atrocious war crimes.” He added, though, that Australian defence minister Richard Marles’s claim that Israel was acting within the rules of war indicated only that Marles was “poorly briefed.”

One stark Israeli violation, Saul wrote, was its medieval “complete siege” of Gaza, with no electricity, no food, no water, no fuel. “A sixteen-year blockade has already debilitated Gaza. This latest turning of the screw is unlawful and could constitute the war crime of starving civilians. It could also be unlawful collective punishment if it aims to retaliate against all Gazans for Hamas’ sins.”

Obama on Gaza

Israel has a right to defend its citizens against such wanton violence, and I fully support President Biden’s call for the United States to support our long-time ally in going after Hamas …. But even as we support Israel, we should also be clear that how Israel prosecutes this fight against Hamas matters. In particular, it matters — as President Biden has repeatedly emphasized — that Israel’s military strategy abides by international law, including those laws that seek to avoid, to every extent possible, the death or suffering of civilian populations. Upholding these values is important for its own sake — because it is morally just and reflects our belief in the inherent value of every human life. Upholding these values is also vital for building alliances and shaping international opinion — all of which are critical for Israel’s long-term security.

This is an enormously difficult task. … Still, the world is watching closely as events in the region unfold, and any Israeli military strategy that ignores the human costs could ultimately backfire. Already, thousands of Palestinians have been killed in the bombing of Gaza, many of them children. Hundreds of thousands have been forced from their homes. The Israeli government’s decision to cut off food, water and electricity to a captive civilian population threatens not only to worsen a growing humanitarian crisis; it could further harden Palestinian attitudes for generations, erode global support for Israel, play into the hands of Israel’s enemies, and undermine long term efforts to achieve peace and stability in the region. …

And while the prospects of future peace may seem more distant than ever, we should call on all of the key actors in the region to engage with those Palestinian leaders and organizations that recognize Israel’s right to exist to begin articulating a viable pathway for Palestinians to achieve their legitimate aspirations for self-determination — because that is the best and perhaps only way to achieve the lasting peace and security most Israeli and Palestinian families yearn for. …Here are links to some useful perspectives and background on the conflict:

●Israel Is About to Make a Terrible Mistake by Thomas L. Friedman

● ‘I Love You. I Am Sorry’: One Jew, One Muslim and a Friendship Tested by War by Kurt Streeter

● A Timeline of Israel and Palestine’s Complicated History by Nicole Narea

● Gaza: The Cost of Escalation by Ben Rhodes.

For years, Netanyahu propped up Hamas. Now it’s blown up in our faces

Tal Schneider’s * comment in the Israel Times.

For years, the various governments led by Benjamin Netanyahu took an approach that divided power between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank — bringing Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas to his knees while making moves that propped up the Hamas terror group.

The idea was to prevent Abbas — or anyone else in the Palestinian Authority’s West Bank government — from advancing toward the establishment of a Palestinian state.

Thus, amid this bid to impair Abbas, Hamas was upgraded from a mere terror group to an organization with which Israel held indirect negotiations via Egypt, and one that was allowed to receive infusions of cash from abroad. …

For years, the various governments led by Benjamin Netanyahu took an approach that divided power between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank — bringing Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas to his knees while making moves that propped up the Hamas terror group.

The idea was to prevent Abbas — or anyone else in the Palestinian Authority’s West Bank government — from advancing toward the establishment of a Palestinian state.

Thus, amid this bid to impair Abbas, Hamas was upgraded from a mere terror group to an organization with which Israel held indirect negotiations via Egypt, and one that was allowed to receive infusions of cash from abroad. …

Most of the time, Israeli policy was to treat the Palestinian Authority as a burden and Hamas as an asset. Far-right MK Bezalel Smotrich, now the finance minister in the hardline government and leader of the Religious Zionism party, said so himself in 2015. …

Hamas became stronger and used the auspices of peace that Israelis so longed for as cover for its training, and hundreds of Israelis have paid with their lives for this massive omission.

The terror inflicted on the civilian population in Israel is so enormous that the wounds from it will not heal for years, a challenge compounded by the dozens abducted into Gaza.

Judging by the way Netanyahu has managed Gaza in the last 13 years, it is not certain that there will be a clear policy going forward.

Edward Feser hops into scientism — again

A well written piece on a hobby horse of mine. A review some schoolboy atheism by a guy called Peter Atkins and another book by Paul Feyerabend. I have nothing against atheism, but I do object to people who traduce all metaphysics while remaining oblivious to the fact that they’re (inadvertently) doing metaphysics.

Scientism is the view that all real knowledge is scientific knowledge—that there is no reliably objective, rational form of inquiry that is not a branch of science. It is a key ingredient of the work of New Atheist writers like Richard Dawkins and the late Christopher Hitchens, and its proponents dismiss philosophy's and theology's claims to provide distinctive but equally rational and objective avenues to truth. But the view faces a notorious problem: scientism is not itself a scientific thesis, but a metaphysical one. Hence it is either self-defeating, or implies so broad a construal of what is allowed to count as "science" that the claim that all real knowledge is scientific knowledge becomes trivial. …

As E.A. Burtt warned long ago in his classic book The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science (1924), those who dismiss metaphysics in favor of their preferred conception of scientific method succeed only in making a metaphysics of that method itself. They cannot escape philosophy, but do it badly precisely because they insist that they are doing something else. Atkins's book joins the recent philosophical efforts of Richard Dawkins and Stephen Hawking in confirming Burtt's prophecy. But in the final analysis On Being fails even as bad philosophy, because it does not even attempt to persuade those who do not already share Atkins's faith-based view of the world. It is a purely devotional work, and a Manichean one—a paean to scientism intended to fortify Atkins's co-religionists in their twilight struggle with the dreaded fundamentalist enemy.

None of this would have surprised the late philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend, who once complained to his colleague Wallace Matson:

The younger generation of physicists, the Feynmans, the Schwingers, etc., may be very bright; they may be more intelligent than their predecessors, than Bohr, Einstein, Schrödinger, Boltzmann, Mach, and so on. But they are uncivilized savages, they lack in philosophical depth…. [Quoted in Imre Lakatos and Paul Feyerabend's For and Against Method, 1999.]

When we consider that Feynman and Schwinger were greater figures than Atkins, Dawkins, or Hawking, the decline in philosophical self-awareness among contemporary scientists is stark indeed. But it is not their lack of philosophical acumen per se that is Feyerabend's concern in The Tyranny of Science, a recently translated series of lectures delivered in Italy in 1992, two years before his death. His target is rather the dogmatic, ideological thinking that has in many quarters come to surround science, and which threatens to stifle other, equally legitimate forms of inquiry. (It seems the book's title is an editor's, not Feyerabend's own. The Tyranny of Scientism would have been more appropriate, if less catchy.)

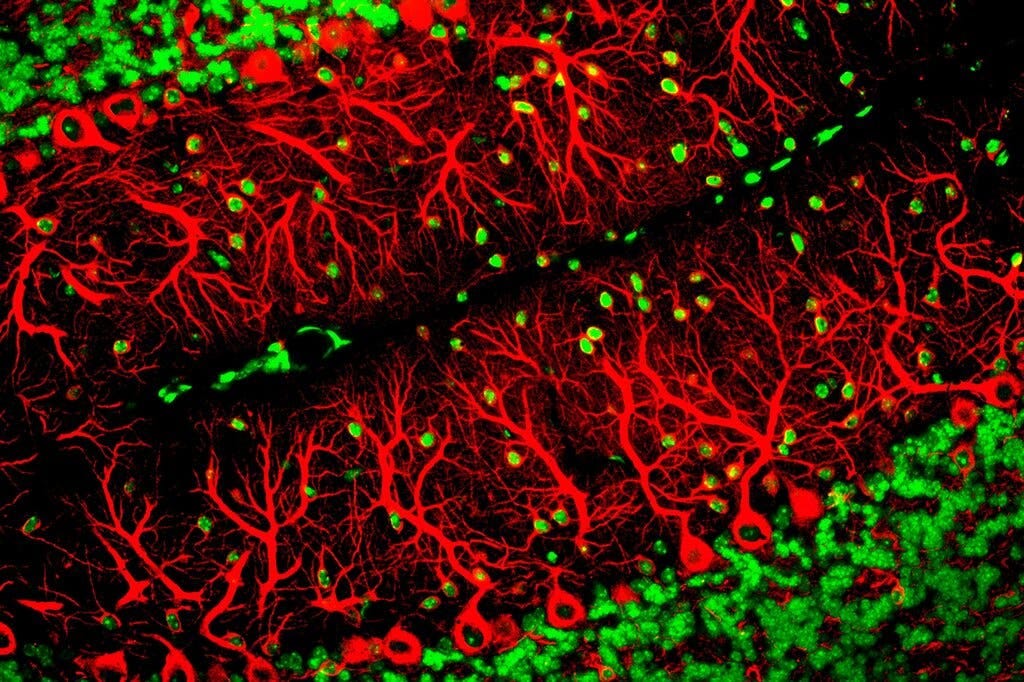

There are 3,300 odd types of braincells

(How come most of us seem to only have a few I hear you cry!) Anyway, don’t thank me for this post, thank the oddly titled and generally wonderful aggregation website 3 Quarks daily.

An international team of scientists has mapped the human brain in much finer resolution than ever before. The brain atlas, a $375 million effort started in 2017, has identified more than 3,300 types of brain cells, an order of magnitude more than was previously reported. The researchers have only a dim notion of what the newly discovered cells do. The results were described in 21 papers published on Thursday in Science and several other journals.

Ed Lein, a neuroscientist at the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle who led five of the studies, said that the findings were made possible by new technologies that allowed the researchers to probe millions of human brain cells collected from biopsied tissue or cadavers. “It really shows what can be done now,” Dr. Lein said. “It opens up a whole new era of human neuroscience.”

Power workers big losers from plant closures

Twelve coal-fired plants closed between 2010 and 2020, and now a deep dive [A shallow dive will never do — ed. ] into the tax records of workers in that industry provides us with the first systematic insight into what happened.

The study we carried out for the e61 Institute along with colleague Lachlan Vass examined taxation microdata to track the earnings trajectories of Australians who received redundancy payments between 2010 and 2020 by industry.

Our study … Four years after being made redundant, the workers in coal-fired power plants earned 50% less. On average across all industries, the workers made redundant earned only 29% less.

There are at least four reasons why the incomes of displaced coal-fired power station workers are likely to be lower than the incomes of other displaced workers.

One is that many coal-fired power plant workers possess highly job-specific skills (related to operating specialist equipment) that aren’t readily transferable to other jobs, or at least not to other jobs in that location.

Another is that many coal-fired power plant workers derive high wages from strong union representation, meaning they are likely to earn less if they switch to less-unionised sectors.

Yet another is that coal-fired power plants are often a major source of local employment and provide support to other employers, meaning that when they close the overall unemployment rate in their region increases, making it hard for the workers they displace to get good jobs unless they move.

And another is that they are usually older. Bureau of Statistics data suggests that in 2010 55% of workers in coal-fired power plants were aged 45 or older compared to 35% in the economy at large.

Workers aged 40 and over do much worse after redundancies than younger workers, and workers in coal-fired power plants even more so.

Important viewing if you’re concerned about a whale running into you

Lesson: whales should be more careful

Emerson’s self-reliance: 21 takeouts

A few years ago Justin Murphy started IndieThinkers which seeks to build online the kind of intellectually curious atmosphere and mentoring of thought that used to be nurtured within universities (no really!). It has been tweaked a little and now describes itself as “An accelerator for independent writers working on the internet.” Be that as it may Justin took his charges usually (in their 20s and alas, probably about 70+% male) through Emerson’s essay “Self-reliance”. They produced this list:

1. Most people do not trust their own beliefs. The essence of genius is simply to trust yourself—to infer that whatever seems most true in your heart is most true in reality—and for everybody else, too, despite whatever they may claim.

2. There is hardly anything more painful than lacking the courage to voice a belief, only to hear someone else express it later.

3. When we admire the Great Men and the Great Books, we often do so mistakenly: For the great men and great books are not examples of revering great men and great books! The Great Men and Great Books are often examples of self-reliant individuals disrespecting the previous Great Men and Great Books by irreverently trusting their own inner calling. If you really admire Great Men and Great Books then you must have the courage and self-trust to not put them on a pedestal; you must wake up every morning trusting that your inner light is every bit as bright.

4. Learning to interpret your inner light is a skill that must be practiced continually over time. It is not "anything goes." One must be accountable to it, as if it is an external constraint. One can be more or less accurate in reading it.

5. If you ever envy anyone, it is only because you are ignorant—either about their hidden failures and sufferings, or about your own abundance and potential.

6. Absolutely no other person knows, or can know, what you are capable of. It is in nobody's interest—including your parents, your spouse, your peers—to fully appreciate your maximum potential. Society systematically underestimates you, for its own ulterior motives.

7. Nothing great is ever produced without courage. If you are not a little scared to do it, then it is not God's work. Goodness must have claws.

8. Self-reliance works because the inner light is divine, it is straightforwardly a relationship to God.

9. Amor fati. Love everything about your station. No matter how lowly or failed or unimpressive your conditions, if you give honest voice to them with great spirit and courage then your genius can be as substantial as anyone's.

10. The accuracy and goodness of the child's naive pronouncements corroborate the inner light.

11. The inner light decreases in clarity as we ascend in society.

12. The integrity of your own mind should be your first priority. This priority should be non-negotiable because it is upstream of everything else in life, except for the divine (to which it is connected).

13. Truth is more important than love because truth allows for authentic love and prohibits false love, whereas mere love allows for false love which is not love at all.

14. What society calls good and bad is often completely wrong, and often systematically wrong for ulterior reasons. A mature person has no choice but to decide what is good and bad from first principles, and any ultimate first principle must involve, to some degree, the inner light.

15. Naiveté and provincialism are underrated, good manners and fine speech are overrated.

16. Travel is for the unadventurous.

17. Intelligence and knowledge are overrated, honesty and courage are the more scarce factors: Alone they are enough to produce the greatest work in the world. If you feel you can't compete on intelligence and knowledge, crush your competition with honesty and courage!

18. Consistency is nothing to worry about. A concern for consistency marks a weak mind and weak spirit who is not self-reliant. Be honest at all times, and over the course of your life, you will naturally amount to a meaningful coherence—despite any number of oscillations or missteps.

19. Never quote a saint or a sage when you can learn from them, digest their teachings, and restate their truths in your own voice. How do you think they became a saint or sage? The truth is common property.

20. Strong intellects who do not believe in God will generally not learn much from the inner light; they do not recognize truth unless it comes in the phraseology of society.

21. Whenever you are getting closer to the good, you can be certain that it will not come in the form of someone else's words. You will not know it by pre-existing signs. The correct path for any individual is necessarily unique, strange, and incommensurate.

You think you’ve got it bad!

2023 Paddington Art Prize Winner.

From the Guru, the bagman and the sceptic

I’m loving this book and will be interviewing him in the not too distant future. Here is Chapter 8.

The eighteen-year-old Anna Freud, accompanied by Anna Hammerschlag Lichtheim (a family friend) arrived in Southampton on 17 July 1914, having sailed from Hamburg. Waiting for her on the dock, with a bouquet of flowers, was Ernest Jones. A regular visitor to the Freuds’ Berggasse apartment, he had known Anna – the youngest of the six children – since she was twelve. She had just finished school and embarked on this holiday hoping to improve her English before starting teacher training. Jones was now thirty-five and had thoughts of marriage. Lina, of course, was out of the question – his ambition was much higher. The prospect of becoming Sigmund Freud’s son-in-law was so intoxicating that he talked about it to Edith Eder, his patient (and probable lover), wife of his close friend and fellow psychoanalyst, David Eder.1 Jones also foolishly confessed his interest to Loe, who wrote immediately to warn Freud. He recognised Jones’s usefulness to the cause of psychoanalysis and to him personally, but the thought of this now middle-aged seducer taking his beloved daughter was more than he could bear. Freud wrote to Anna on 17 July in a state of panic: ‘I know from the best sources that Dr Jones has serious intentions of marrying you.’ He described Jones as ‘a very valuable co-worker’, before pointing out his age, his ‘very simple family’ background, his lack of tact and consideration, his ‘need of moral support’. She should not even consider marriage, he advised, for at least five years, and she should look to Loe for guidance in ‘feminine matters’.

The agitated Freud wrote again five days later, warning Anna not to allow herself to be alone with Jones: ‘When left to himself, Jones shows a tendency to put himself into precarious situations and then to gamble everything, which for me would not guarantee your security.’ He also sent a warning salvo to Jones: ‘She does not claim to be treated as a woman, being still far away from sexual longings and rather refusing man. There is an unspoken understanding between me and her that she should not consider marriage or the preliminaries before she gets two or three years older. I don’t think she will break the treaty.’ Freud suspected that Jones was using Anna to get back at him for his part in the break-up with Loe, writing to Ferenczi that he did not want ‘to lose the dear child as an act of revenge’.

Freud needn’t have worried: Jones behaved impeccably, taking Anna on day trips to the countryside, to the theatre, to restaurants. Loe came along to chaperone, keeping watch ‘like a dragon’. When war appeared imminent, Jones (with the help of Jones the Second) arranged for Anna’s safe passage back to Vienna. He wrote – rather pointedly – to Freud on 27 July: ‘She has a beautiful character and will surely be a remarkable woman later on provided that her sexual repression does not injure her. She is of course tremendously bound to you, and it is one of those rare cases where the actual father corresponds to the father-image.’ Freud’s panic over Jones’s interest in Anna was misplaced. She wasn’t interested in him, or indeed, any man. Freud had hoped that she might marry one of his Viennese Jewish disciples, but Anna’s sexual orientation was to women; throughout the four years of the war, she fantasised about being reunited with Loe Kann.

Anna Freud was one of the few women wooed by Jones who was impervious to his charisma. In 1974, Anna – now in her late seventies – wrote about this episode: ‘Naturally I was flattered and impressed, though not without a lurking suspicion that his interest was directed more to my father than to myself.’ What could be more off-putting in a suitor? They maintained superficially cordial but distant relations until Jones’s death. Although Jones was instrumental in rescuing the Freuds after the Nazi occupation of Austria in 1938, Anna felt that he had betrayed her when he later sided with Melanie Klein in the bitter English psychoanalytic civil war in the mid-1940s. Jones, for his part, protested that he was neutral in this dispute, and treated Anna with the utmost courtesy and respect; he needed her cooperation for the great work of his old age – his three-volume biography of her father. In the early 1950s, while researching this biography, he read Freud’s letters to Anna warning her about him; Jones was aggrieved that Sigmund Freud thought he was motivated by revenge, and that Anna Freud thought he was using her to get closer to her father. He wrote to Anna: ‘I found you (and still do) most attractive. It is true I wanted to replace Loe, but felt no resentment against her for her departure, it was a relief from a burden. In any case, I have always loved you, and in quite an honest fashion.’

*

In 1918, Anna began analysis with her own father; it was supposedly a ‘training’ analysis. Anna had now decided on a career as a psychoanalyst, which Freud approved of, even though he forbade her to study medicine – she would be a ‘lay’ analyst. Patrick J. Mahony called this analysis – with some justification – ‘impossible and incestuous, an iatrogenic seduction and abuse of his own daughter’. Anna’s adolescence had been difficult, with periods of depression and an eating disorder; in his analysis, her father explored these problems, along with her masturbation fantasies of beating. Freudian apologists explained this violation away with the phrase Quod licet Jovi, non licet bovi – ‘What is permitted to Jupiter is not permitted to an ox’ or, more prosaically, in the Yiddish ‘Der Reb meg’ – ‘The Rabbi is allowed’.

After three years, Freud was disappointed with the progress of the analysis, and asked Lou Andreas-Salomé to ‘assist’ him. Andreas-Salomé, now in her late fifties, was a Russian-born collector of great men, famous for her intimacies with Nietzsche (whom she drove to distraction) and Rilke (it was she who persuaded him that ‘Rainer’ was a more stylish name for a poet than ‘René’). She came to Freud for analysis in 1912; he encouraged her to jump the couch and become an analyst herself, which she did, despite her admission that she lacked ‘interest in ordinary people’, and Freud’s shrewd assessment that she was ‘a narcissistic cat’. Although she refused to sleep with her husband (the hapless Friedrich Carl Andreas) for the entire duration of their forty-three-year marriage, Lou had numerous lovers, including the analyst Victor Tausk, eighteen years her junior.2 Freud was entranced by this fabulous creature, his muse until she was displaced by the even more fabulous Princess Marie Bonaparte. Although he was uxorious and sexually unadventurous, Freud basked in the admiration of these flattering and flirtatious women.

Lou Andreas-Salomé and Anna shared interests in beating fantasies, anal sexuality and masochism. Lou, according to Anna, helped her in a ‘strange and occult way’. She went back into analysis with her father in 1924. After years of intimate access to the most secret and hidden thoughts of his daughter, it finally dawned on Freud, after a thousand hours of analysis, that Anna was not the marrying kind. This suited him just fine. After his first operation for cancer of the palate in 1923, she became his main carer, closest confidante, professional colleague and defender of the psychoanalytic faith.

Anna had first attended the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society in 1919 as a visitor; in 1922, she presented her first paper on beating fantasies, following which she was admitted as a member. Having trained as a teacher, Anna decided she would like to work with children. She was influenced by the work of Hermine Hug-Hellmuth (acknowledged to be the first child analyst); she was not diverted from this ambition when, in 1924, Hug-Hellmuth was murdered by her eighteen-year-old nephew Rolf, whom she had been analysing for several years. By 1925, Anna was teaching at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Training Institute.

*

Anna’s life partner was Dorothy Tiffany Burlingham, an American heiress who arrived in Vienna with her four children in 1925. Dorothy, the daughter of the artist Louis Comfort Tiffany, was fleeing from her marriage to the surgeon Robert Burlingham. Robert, the scion of a wealthy New York family, had bipolar disorder, with episodes of severe mania. As the marriage floundered, Bob, their eldest child, developed asthma and eczema, and became ‘difficult’ with temper tantrums and petty thieving. The boy’s problems began early on, when his mother handed over his rearing to a nanny, who regularly locked him in a closet. Dorothy, who had heard about Anna Freud’s work with children, decided to move to Vienna so Bob could be analysed; it was also a useful pretext to get away from her husband. Robert objected, but Dorothy was determined; on 1 May 1925, she and Bob (ten), Mabbie (eight), Tinky (six) and Mikey (four) arrived in Europe. Their father was heartbroken; his friend Constance Buffin wrote that taking the children away was ‘like refusing water to a man dying of thirst’.

En route to Vienna, they stopped in Geneva, where Dorothy engaged the psychologist Émile Coué, who ‘treated’ Bob by having him stand facing a wall and endlessly repeat: ‘Every day in every way I am getting better and better.’ At the start of his analysis, Anna Freud described Bob as ‘a boy of ten with an obscure mixture of many anxieties, nervous states, insincerities, and infantile perverse habits’. Bob initially refused to cooperate, but Anna won him over by her willingness to do small favours and to excuse him from punishment. As the analysis progressed, Anna ‘discovered’ homosexual tendencies in the boy, tendencies that (whatever her own inclinations) she decided must be nipped in the bud. His superego, she deduced, had detached itself from parental influence; if she could reinstate the Oedipal rivalry with his father for Dorothy, ‘normal heterosexual development’ could proceed. Anna next turned her attention to Mabbie. While Bob had reacted to the breakdown of his parents’ marriage by becoming an asthmatic delinquent, Mabbie instead became a tearful, sensitive, clingy girl, desperate to please her analyst.

Anna became a surrogate parent to the four Burlingham children and Dorothy’s closest friend; in 1927, she told her father that she and Dorothy shared ‘the most agreeable and unalloyed comradeship’. Dorothy, naturally, had gone into analysis herself, going first to Theodor Reik (one of the first lay analysts), then to Freud himself; just as naturally, she jumped the couch and began psychoanalytic training. The annexation of the Burlinghams was complete when Dorothy moved into an apartment two floors above the Freuds in the same building on Berggasse; Dorothy installed a private telephone line connecting the two households. The Burlinghams were tended to by two maids, a governess and a driver.

Robert Burlingham, nursing vain hopes of a reconciliation, came to Vienna in 1929, where he had a frosty meeting with Anna; an even more hostile exchange took place the next day between Sigmund Freud and Robert’s father, Charles Culp Burlingham. In his biography of Dorothy, The Last Tiffany, Bob’s son Michael John Burlingham wrote: ‘The cornerstone of Sigmund Freud’s self-mastery program for Dorothy, then, was an intellectual preoccupation so engrossing as to reroute her sexual drive. Desexualisation is not an attractive concept, but that was nevertheless Freud’s intent. His denials to Robert aside, he was raising an absolute barrier between husband and wife.’

Anna combined the roles of psychoanalyst, teacher and co-parent for the Burlingham children; she believed that the analysis of children could only succeed with such an all-encompassing approach. By 1935, Bob was twenty and had undergone 2,000 hours of analysis. Mabbie, who had also been in analysis for ten years, she proclaimed ‘the most successful’ of her early cases. Tinky – who resisted psychoanalysis – endured a mere three years of Anna’s attentions; Mikey, who was born after his parents’ separation, appears to have escaped completely. Anna steadfastly opposed any contact between Robert Burlingham and his children. On 27 May 1938, he obligingly committed suicide by throwing himself from the window of his fourteenth-floor New York apartment. Sigmund Freud wrote to Dorothy, ‘to remind you how little guilt, in the ordinary sense, there was in your relationship with your husband’.

Despite – or because of – the thousands of hours of analysis, Bob and Mabbie continued to have ‘problems’, unable to divest themselves of their dependence on Anna. Bob inherited his father’s bipolar disorder, but Anna opposed the drug therapy (lithium) that might have stabilised this condition. Instead, he self-medicated with alcohol, and experienced regular episodes of mania and delirium tremens. A heavy smoker, he developed emphysema and angina, and died of a heart attack in January 1970, aged just fifty-four. Mabbie, a frustrated artist, returned frequently to Anna for an analytic top-up whenever any problems arose with her marriage or her children. In late 1974, she flew from the US to London and moved into the Hampstead home shared by Dorothy and Anna, where in July 1975, she took an overdose of sleeping tablets and died a week later in hospital. Michael John Burlingham – with heart-breaking understatement – wrote:

Bob and Mabbie’s children particularly found it hard to see Dorothy and Anna Freud in a positive light. When the turbulence subsided, what remained was a nagging image: that instead of, or perhaps in addition to, having received a golden key, Bob and Mabbie had been loaded with an enormously heavy cross, and bear it they did, to the very altar of psychoanalysis. There remains the ironic conclusion that psychoanalysis had been foisted on them unnecessarily, and when dependent upon it, had not helped them. Then, when they had really needed help, Freudian ideology had discouraged them from seeking it, for example, in the realm of pharmacology.

*

The Burlingham children were not Anna’s only victims; their tragedy would be re-enacted in thousands of American families. When divorce rates rose dramatically in the US during the 1960s and 70s, the family courts looked to psychologists for guidance on child custody. Anna Freud teamed up with the child psychiatrist Albert Solnit and the legal academic Joseph Goldstein.3 They came up with the idea that every child has one ‘psychological parent’ to whom the child looks for security and affection. The psychiatrists and psychologists who were now routinely called in as experts by the divorce courts generally took the Goldstein-Freud-Solnit line, and these courts saw their role as the identification of the ‘psychological parent’, who would be granted full custody; in the great majority of cases, this was the mother. Freud and her collaborators recommended that the parent granted custody should have the right to ‘control’ (i.e. prevent) visitation by the noncustodial parent. Post-divorce contact between parents was discouraged as being inherently dangerous, and fathers commonly disappeared from their children’s lives. Although Goldstein, Freud and Solnit4 elaborated their ideas in a series of books,5 the evidential basis for their claims was shaky. Anna’s beliefs about the role of fathers were formed by her experience with the Burlingham children; the fate of two of these children – Bob and Mabbie – was a closely guarded secret until Michael Burlingham’s biography of his grandmother appeared in 1989, seven years after Anna’s death.

*

The Burlingham children – like many psychoanalytic experiments – led tragic lives, but the relationship between Dorothy and Anna was sunny and cloudless as a summer’s day. Dorothy ran their various households in Hampstead, Suffolk and West Cork; they enjoyed knitting and weaving together, and steadfastly refused to identify as homosexuals. Sigmund Freud once remarked that he stood ‘for a much freer sexual life’, but that he had ‘made little use of such freedom’. His daughter was similarly lukewarm; one analysand referred to her ‘spinsterish holiness’. Their secretary, Gina Bon, wrote an affectionate memoir for American Imago in 1996: ‘I felt there was a kind of unfraught companionship, free of tensions or the kind of conflicts born of power struggles or jealousies that can prove so destructive in some marriages.’