Help me help the community independents

Well, here we are again. Long time readers of this newsletter may recall at the last election I was in a safe(ish) seat (Melbourne Ports) and so nothing I did in my own seat made a difference. At the same time as I wrote then:

I think the emergence of independents is incredibly valuable. I didn’t need to agree with Tony Windsor to have confidence that he was trying to represent the interests of his community and country. But it’s getting increasingly hard to rely on the parties to do so.

The worst decision we made as a country in recent times was to abolish carbon pricing which we did despite most of the parliamentarians voting to do so knowing it was bad for us all. Why did they do it? Because as Peta Credlin said, it was good retail politics. Likewise the bulk of British parliamentarians voting for what is now the unfolding disaster of Brexit knew it was hare brained.

Now we have the farcical nightmare of AUKUS - the deal you have to buy subs that the sellers won’t give you unless they feel like it. Again, retail politics is why we have it, in this case with reverse pike. The Coalition might have thought it was a good idea. The ALP does not and could easily have reversed it. But didn’t because even though it’s little more than a tribute payment and it marches us up to the front line in the next world war, the retail politics are marginally in its favour - at least as judged by the comms folks.

The more I think about it, the more I think expecting a politician to say what you think makes sense - and being offended and censorious when they don't - is like being disappointed with a merchant for not charging the 'just price'!!

Anyway, as last time, I asked Simon Holmes a Court which of the community independent candidates Climate 200 was backing he thought were closest to a knife edge. After all, that’s where there’s most gain for the marginal extra dollar of funds raised - did I mention I’m an economist?

Simon suggested Kate Chaney who was an impressive candidate last time. I also know her a little and think she is a very decent, and capable person. But Gina is bankrolling her opponent. So she needs our help.

So join me in donating to her campaign. In general, the ATO tells us that donations of up to $1,500 are tax deductible. And, if you click on the link below, Kate’s campaign will know that you came via this newsletter and I’ll match any and all donations up to $5,000.

From another time

Australia can defend itself

On Monday this week I attended a one day conference on Australia’s security convened and chaired by Malcolm Turnbull. I was shocked, horrified actually to see senior figures arguing that criticisms of AUKUS would undermine the defence effort. Srsly! Even Dennis Richardson indicated sympathy for this argument. Well, I guess it shouldn’t be completely ignored, but I can’t see how you invite decent debate without mostly ignoring it. And if debating it undermines our capacity to deliver the project, I guess we should have gone for something a little more modest - and less farcical. As we were. In any event, I continue to think Sam Roggeveen talks a lot of sense in regard to Australia’s capacity to defend itself. He calls it the echidna defence, but one might also call it the Russian defence. It’s further for potential adversaries to get to Canberra and Sydney than it ever was for Russia’s adversaries to get to Moscow.

I'd like to start with a simple declaration: Australia can defend itself with a less reliable American alliance partner. In fact, Australia can defend itself even if there is no alliance at all.

I'd like to examine this issue in two ways: as a military problem and as a political one.

The military problem, it seems to me, is relatively straightforward. Australia is not that hard to defend. We are not Taiwan, or South Korea, or Israel, or Poland.

We don't have an enemy on our doorstep. Beijing is closer to Berlin than it is to Sydney, and when it comes to using force against Australia, distance matters a great deal.

Being far away from threats remains a tremendous asset. The 2024 National Defence Strategy says, "Technology has already overturned one of Australia's long-standing advantages – geography".

But that is a substantial overstatement.

The Chinese naval flotilla that recently circumnavigated Australia had to make a journey of over 7,000 kilometres just to sit off the coast of Eden to conduct gunnery practice. In wartime, if it had not been sunk, it could have delivered at best a few dozen cruise missiles onto our landmass. ...

Now of course, in years to come the Chinese fleets will get bigger, and China will deploy new bombers, and more missiles. Australia's task, therefore, is build its capacity to sink the ships and submarines that threaten us, and shoot down the incoming aircraft and missiles. That task will get harder as China's power grows, but it is perfectly achievable for Australia, even without the alliance.

But the starting point must be to use distance to our advantage. At present, we're treating it as a barrier to be overcome – that's what AUKUS is about. I say, if China ever wants to threaten Australia, let the PLA cross that distance. Our task, when their ships and missiles and aircraft get close enough, is to cause them unacceptable damage.

I have called this an Echidna Strategy. Now, I grant, the echidna is a slightly ponderous, even comical, creature. But it is hardy. It's a survivor. And it is perfectly adapted to its environment. With an Echidna Strategy, Australia looks benign and friendly to nations that mean us no harm, and spiky and indigestible to those that do. ...

It seems we're not content with the strategic gift handed to us by our favourable geography. We yearn to be relevant. We want to be with the Americans at the head table, and we fear being left out of their considerations.

AUKUS is a symptom of this anxiety. After all, on the day AUKUS was announced, I doubt any fair-minded Australian observer would have said that the alliance was in trouble, and that a $368 billion gesture was required to rescue it. In fact, the alliance was already in rude health, as intimate as it had ever been.

So, when AUKUS was announced on 15 September 2021, it resembled a bizarre scene at an auction. The hammer had already come down, and the auctioneer had announced "sold to Australia".

To which Australia responded, "Thank you, but we'd like to make another bid". ...

The trouble for alliance supporters is that a longer historical gaze brings no more comfort, because we can see a long succession of unmet American promises to prioritise Asia. In the face of China's dramatic military modernisation, the United States has done little. US forces deployed to Asia today are of roughly the same size as in 1991.

But let's not blame the Americans. It is perfectly rational behaviour. Taking on China would be a daunting task, the hardest thing America has ever had to do as a great power. But it's not an essential task, because the United States is a highly secure country which will remain perfectly safe even if China dominates Asia. ...

Now the veil has been lifted and we are left to sort things out for ourselves. It won't be the first time Australia has been forced to be free. The fall of Singapore, the "east of Suez" policy, the Guam Doctrine, the stillborn Pivot to Asia, the abandoned Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Throughout our history, Australia has had to grasp its independence by degrees. The steady retreat of American influence in Asia, now accelerated under [President] Trump, merely completes that evolution. ...

We've always done the big things our own way: the Australian ballot, compulsory voting, federalism, superannuation, health, education, immigration, firearms. So why not defence? There's no reason for Australia to lack self-confidence.

I began by saying that Australia can defend itself with a less reliable America. I end by saying that we must. There is no going back to late 20th century American dominance of Asia. This isn't about Trump, and it isn't a passing storm. America won't return to "normal".

We need to plan for a more independent, post-American, future not out of misplaced nationalism, and certainly not out of spite or animus towards the Americans. We should do it because we must.

Things that weren’t done in the 19th century

Like smiling. Well not for the cameras. Click through to find out why.

Felix Martin on the ‘inbetweeners’ - like us

An interesting column straining to look for upsides from my friend Felix Martin.

If there was any remaining doubt, the unipolar U.S. moment is over. On January 30 newly installed US Secretary of State Marco Rubio called time on the country's three-decade long run as the sole arbiter of global affairs, calling it an "anomaly". … President Donald Trump's blanket tariffs on global trading partners, which he unveiled on Wednesday, further underscore the shift.

International investment allocations, however, remain glaringly out of sync with this epochal geopolitical shift. For the past decade and a half, American capital markets have been the only game in town. As of December, net foreign ownership of U.S. assets hit an all-time high of just over $26 trillion, or almost 90 per cent of America's GDP, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. The U.S. stock market is so gargantuan – and richly valued - that it accounts for almost three-quarters of the MSCI World Index of developed market equities. Three companies – Apple, Nvidia and Microsoft - each represent higher shares of the MSCI ACWI Index of global equities than the entire UK stock market. When it comes to investing, it as if the American unipolar moment never ended.

The net result of this almighty disconnect is the prospect of a generational shift in asset allocations as investors seek to realign their portfolios with the new geopolitical reality. Where they should redeploy their capital, however, is no simple question. …

One compelling category of investment destinations might be termed "inbetweeners": those major emerging markets which combine investable financial markets with the economic and geopolitical heft to avoid wholesale alignment with either the U.S. or China. Investors will doubtless disagree about exactly which jurisdictions meet these two criteria. But at a minimum Brazil, Turkey, South Africa, the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, India, and Indonesia make the grade. That group alone makes the inbetweeners too big to ignore. They collectively account for more than a quarter of the globe's working-age population; nearly a fifth of world GDP measured at purchasing power parity; just under a sixth of global active military personnel; and around a tenth of world trade and defence spending, respectively.

The thesis that strategic neutrality can yield tangible economic advantages, meanwhile, has historical precedent to back it up. In 1961, the leaders of 25 developing countries founded the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) with the express intent of preserving autonomy in trade, technology, and financial relations with the Cold War's two superpowers. Over the next two decades, that strategy paid off. Per-capita income growth in NAM countries notably outperformed the world average. …

In today's era of far more integrated global trade and capital markets, the benefits of being on good terms with both the world's superpowers are undoubtedly even bigger. For a taste of the advantages, look no further than financial centres such as Dubai and Singapore – the boomtowns luring international bankers from London and New York – or former backwaters such as Kazakhstan which have become vibrant hubs of east-west trade. Playing the middleman in a global economy ten times the size it was in the days of the original NAM is at least ten times as valuable. Forget the regulatory and tax arbitrage that has been the key to optimising corporate capital structures and supply chains for last three decades. It is geopolitical arbitrage which will unlock resilience and profitability in the new Cold War – and it is inbetweeners that offer the obvious go-to locations for that service.

Yet while non-alignment served the original NAM very nicely in the 1960s and 70s, its members' performance in the 1980s was less impressive. … It turned out that the independence afforded by being indispensable to both sides in a polarised world could easily slip into policy indiscipline.

That is a cautionary tale for investors attracted to today's inbetweeners. Between 2000 and 2014, Saudi Arabia ran an average fiscal surplus of nearly 8% of GDP. For the last decade, extravagant investment projects such as the $500 billion NEOM development project have converted that into an average annual deficit of 6% of GDP. Last month, Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan's main challenger Ekrem Imamoglu was detained on corruption charges, sending the country's financial markets into free-fall. …

The biggest threat to the inbetweeners' bid for a share of the coming reconfiguration of global capital flows comes from an entirely different direction, however. The starkest difference between the original Cold War and the latest superpower showdown is the sudden U.S. repudiation of its long-time allies in Europe, North America, and Asia. That raises an obvious possibility. Maybe the real inbetweeners are now closer to home than developed-market investors think. The investment destinations that offer the biggest geopolitical arbitrage opportunity to refugees from the U.S.'s out-of-sync unipolar markets are none other than Europe, Canada, and Japan. [And, if asked, I presume Felix would have added, Australia.]

Lovely photos inspired by old masters

Thanks to subscriber Robert for pointing them out. More detail here.

Bastions of liberal thought or glorified rent-seekers?

A coda to last week’s post - Lockdowns and Liberty - on how we’re in what I call a ‘consumer democracy’ in which the only liberties people really care about and will defend (if they can be bothered) are the liberties to buy and do whatever the hell we want.

Larry Summers answers my question

When I heard some of the early plans of the Trump Administration to withdraw some tax privileges from the largest university endowments, it didn’t particularly raise my expectations, but I did chalk up a ‘win’ for good policy. The size of the really big endowments and what they’re used for (to cream skim for the best DEI targets and subsidise elite MBAs for instance) disclose a good case for reducing tax breaks. I was also thinking of Malcolm Gladwell’s amazing interview with a senior Stanford man who’d raised over $6 bil for its endowment which, from memory, was at that point worth over $100 billion. Gladwell asked him ‘how much is enough?’. Indeed.

Anyway, of course, we also knew if we were paying attention that Trump wasn’t coming after the endowments with Malcolm Gladwell’s ideas in mind. But with endowments of that magnitude, the Ivy League are well placed to ride out Trump’s vengeful madness. Nice to see at least one person pointing that out. But then again, the liberal bedrock of liberal democratic societies is now only part of our institutional muscle memory. It’s not something many people will fight for when push comes to shove - as we saw with Columbia University.

So it was nice to see Larry Summers weighing in. I agree with pretty much everything he says here - including his point that “universities have in large part lost” the moral high-ground.

The U.S. government is trying to bludgeon America's elite universities into submission. At stake is the future of institutions that graduated most of our recent American presidents, the vast majority of Supreme Court justices and that serve as drivers of our prosperity and shapers of our social values.

The Trump administration's threats to withdraw billions of dollars in funding are little more than extortion. They must be resisted using all available legal means. Columbia University's recent capitulation, in which it agreed to a raft of changes in an attempt to avoid losing hundreds of millions in funding, must not be emulated. Each act of capitulation makes the next one more likely. Each act of rectitude reverberates.

As in most confrontations, the merits in this one are far from one sided. Critics of elite universities, including Harvard, where I am a professor, are right that they continue to tolerate antisemitism in their midst in a way that would be inconceivable with any other form of prejudice...

But the Trump administration is not acting in good faith in its purported antisemitism concerns, nor is it following the law in its approach to universities.

President Trump offered praise to a white-supremacist rally that included chants of "Jews will not replace us," publicly dined with Holocaust deniers, made common cause with Germany's Nazi-descendant AfD party and invoked tropes about wealthy Jews. The true motivation behind his attack on universities is suggested by Vice President JD Vance's declaration that the "universities are the enemy."...

Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act appropriately allows that federal funding of universities can be made contingent on their avoiding discrimination. But as a recent statement by a group of leading law professors points out, it also protects against this power's being used to punish critics or curtail academic freedom...

The White House has not confined its efforts to claims about discrimination. The administration seeks to dictate what universities do on matters ranging from student discipline to academic organization to campus policing.

Universities facing those threats should make clear they are willing to negotiate with government officials only over matters covered by statute and through the procedures laid out in the law.

They should make clear that their formidable financial endowments are not there to simply be envied or admired. Part of their function is to be drawn down in the face of emergencies, and covering federal funding lapses surely counts as one...

And to maintain the moral high ground, which universities have in large part lost, they need a much more aggressive reform agenda focused on antisemitism, celebrating excellence rather than venerating identity, pursuing truth rather than particular notions of social justice and promoting diversity of perspective as the most important dimension of diversity...

Institutions such as Harvard, the administration's most recent target, have vast financial resources, great prestige and broad networks of influential alumni. If they do not or cannot resist the arbitrary application of government power, who else can? Without acts of resistance, what protects the rule of law?

I hope and trust, in the time of testing that lies ahead, universities will both reform themselves and stand up to external pressure. Their future and America's are in the balance.

Speaking of Malcolm Gladwell

He’s very eloquent and charming here - at least until he starts using samples of 4 to deduce laws (and even misuses the evidence. He argues that Chamberlain met Hitler and misjudged him but Churchill who didn’t meet him judged him correctly. Then he mentions Stalin. He misjudged Hitler, but also didn’t meet him. Oh well, other than that I enjoyed the segment.

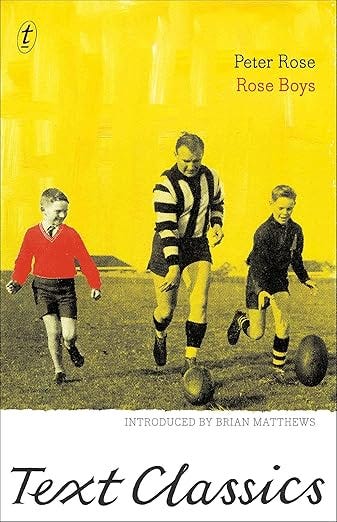

Peter Rose’s exit interview

This was a poignant interview for me for various reasons. Peter Rose when to the same school as me, though he was a year or two ahead of me. His father was Bob Rose, a great footballer who coached his beloved team - my beloved team of Collingwood through numerous years in which they were the dominant team and yet fell at the last hurdle with something going wrong in the Grand Final year after year.

But what made it all most poignant was remembering reading Rose boys, Peter’s memoir of himself, his father and his brother Robert who was a talented sportsman at both football and cricket. Until a car crash rendered him quadriplegic and cast a pall of tragedy over those who loved him. I reproduce extracts from Rose Boys in Heaviosity Half Hour below.

Britain’s Wasted Crisis

I don’t know enough to be sure, but this looks right to me.

Hardly anyone in the British media had a good word to say about Rachel Reeves following her Spring Statement last week. She may have succeeded in restoring her headroom under her fiscal rules, but the left-wing press attacked her for doing so on the backs of the poor by cutting welfare benefits, while the right-wing press blamed her for the Office for Budget Responsibility’s growth forecast being halved this year to 1 percent, making the cuts necessary.

Both attacks are unfair. It is impossible to look at Britain’s soaring sickness benefits bill, which almost uniquely among developing countries has continued to rise since the Covid pandemic, and not conclude there is something seriously amiss. And given the dire economic inheritance from the Tories, I don’t think Reeves has done too badly. Taxes needed to rise and whichever ones she chose, the right-wing media would have attacked her for them.

Nor do I have much truck with those who say she should simply junk her fiscal rules and borrow more as Germany has done. She already changed the fiscal rules last year to allow her to borrow more, and indeed she was able to sneak through another increase in borrowing in her spring statement by classifying some defence spending as investment. But the reality is that she is planning to issue £299 billion of gilts in the next financial year, the second highest total since the pandemic. The fact that gilt yields fell in relief that the gilt mandate was not £300-320 billion as many had expected suggests that the real constraint on Reeves is not the fiscal rules but the willingness of the market to absorb higher issuance.

My criticism of Reeves and Labour is that they are too timid. They are right that the world has changed, but they seem reluctant to rise to the level of events. As I wrote in a column for Byline Times, they are in danger of letting a crisis go to waste. Yes, they have taken some tough decisions that they might otherwise not have ducked, including raising defence spending to 2.5 percent of GDP by 2027 and making those welfare cuts. But the government gives every impression of bowing to events and making no attempt to master them.

The reality is that Reeves will almost certainly face further tough choices come the Autumn when she delivers her next budget. As the OBR noted, it would only take a small rise in interest rates, or continued weak productivity growth, to wipe out her headroom again. The central OBR forecast also doesn’t account for the impact of a Trump a trade war, which would crush growth. At the same time, defence spending will surely need to hit 3% before the end of this parliament. No wonder most City economists expect taxes to have to rise, so why does the government not seize the opportunity arising from a shifting of the Overton window to escape the straitjacket of its manifesto?

If taxes must rise, then why not grasp the opportunity for long overdue far-reaching reform of a tax system filled with incentive-crushing cliff edges at every level of the income scale? When better than now to slash electricity prices by shifting green levies onto general taxation, paid in part by finally raising fuel duties, frozen for over a decade?

Rather than footling around with a small-scale National Wealth Fund tasked with picking industrial winners, now is the time to create a vast Public Wealth Fund to manage all public assets on a commercial basis and improve their returns – as the US Government is considering doing.

Above all, why squander energy and political capital in desperate pursuit of a US trade deal, even at the possible price of altering the UK tax code to suit American corporate interests and sowing division with European allies, when far greater gains could be achieved by rejoining the EU customs union and single market? Indeed, there is no single policy that the Government could pursue that could at a stroke boost the economy, reassure the bond market and revive the desperately sagging stock market.

As Reeves says, the world has changed. Time to smash the emergency glass.

Yvonne Audette

Josephine Baker

I review of a recent book about her. I knew very little about her.

Today we think of Josephine Baker as the personification of the Jazz Age – the skinny black kid from Missouri who took Paris by storm. In retrospect, her show-stopping Revue Nègre act can be read as a subversion of the prejudices of her age. At the time, however, it just looked like a heady cocktail of comedy, exoticism and sex. Scantily garlanded with feathers, dancing to 'barbaric, syncopated music', Baker was 'black poetry', according to Marcel Sauvage, who acted as her ghostwriter.

The fact that she had got to Paris at all was testament to her resilience and spirit. Born into poverty in St Louis in 1906, Baker never knew who her real father was. By the age of eight she was working as a maid. At eleven, she witnessed the devastating racist violence of the East St Louis massacre. Two years later, having dropped out of school, she was scraping together a living dancing on street corners. She was married – the first time at only thirteen – and divorced twice before she was twenty...

Racism was an inescapable theme of her life. One of her early dancing jobs was at the Plantation Club, a Harlem nightclub decorated to resemble the antebellum South and only open to white patrons; perhaps this experience helped inspire the colonial backdrop for her Folies Bergère acts. As a chorus girl at the end of the line, the exuberant fifteen-year-old Baker learned to attract attention by pulling funny faces. Moving to Paris at nineteen, she became a global celebrity and discovered in France a true home. It wasn't just that Parisians appreciated her deficiencies of costume; to her delight they found the colour of her skin beautiful.

The first section of her memoir Fearless and Free, newly translated by Anam Zafar and Sophie Lewis, chronicles this period. It captures a girl – kind, charismatic, mischievous and full of laughter – with barely any education revelling in success and the trappings it brought her. Between dances she would bottle-feed her pet goat Toutoute. Her reminiscences are often as charming as they are rambling and vague...

She describes, too, the tours, during which she met frequent hostility with courtesy and grace. Greeted in Vienna with church-organised demonstrations over her supposed wickedness, she opened her show with a spiritual, 'Sleep, My Poor Baby', 'from back in the slave times when Negroes were good for nothing but dying from exhaustion and despair after being beaten by their very Christian owners'. Then she began dancing

like I always have and always will, not thinking about good or evil but only about my dance, my honest and ever so pure dance, to show humankind and God – who I've been assured is the God of all people whether they're white, black, yellow or red – that there is a youthfulness that is free, eternal and forever, in spite of everything, a great and simple joie de vivre that's enough in itself...

In Josephine Baker's Secret War, Hanna Diamond meticulously documents Baker's clandestine war work for the Free French using previously unseen sources. Employing her celebrity as cover, she was able to move almost freely through Spain, Portugal, the Middle East and North Africa. Officers and diplomats from Axis and Allied forces competed to meet her wherever she went, so she had unique access to intelligence. She hid her reports from customs officials by pinning them to the inside of her clothes or using invisible ink on her scores. After the Americans landed in North Africa in November 1942, Baker became a key point of contact between Allied and Moroccan leaders, many of whom had become her friends.

Her war work informed the civil rights activism that defined her later years, which, with Sauvage, she recorded in her memoirs. Like so many African Americans who had served loyally in both world wars, Baker was devastated when she visited the United States in the late 1940s and 1950s to discover that black people were still segregated. 'Are we just bugs to these good Americans?' she demanded. In 1951, she was refused service at New York's Stork Club; Grace Kelly, who witnessed her dignity at the restaurant, became a devoted friend after this incident. Proudly dressed in her army uniform, she was the only female speaker at the 1963 March on Washington...

The mature activist and devoted Gaullist may seem a far cry from the uninhibited performer who dazzled 1920s Paris, but, as these complementary books show, she was always politically engaged, as well as sexy, funny, bold and irreverent. Her career-defining banana belt act at the Folies Bergère in 1926 may have made the older generation choke over their barley water but they were missing the point. She wasn't trying to corrupt anyone. Instead, she was poking fun at outdated prejudices which the younger generation was starting to shake off. From the start, she understood that, delivered with a smile and a shimmy, her message would be irresistible.

Love's Inevitable Gravity

The Sacred Archaeology of Desire

In one way I think this is very good. I think it’s broadly right. It sits at the background of the book I recently extracted - Elias Dakwar’s The Captive Imagination. It makes a fundamental point which most people never get near - finding it impossible to escape the deep scientism of our age except by imagining that things outside their ken are ‘metaphors’.

But it’s far from good in another way. The proof of the pudding is in the eating. Dakwar brings home some bacon with the depth of his insights. He illuminates modern life. In the case of many others, they spend pretty much every post saying something similar. I’d put Iain McGilchrist of The Master and his Emissary in that category - and on and on he goes.

Here’s what Iris Murdoch thinks about it all. You can see lots of similar quotes from her on this great theme here.

It is in the capacity to love, that is to SEE, that the liberation of the soul from fantasy consists. The freedom which is a proper human goal is the freedom from fantasy, that is the realism of compassion. What I have called fantasy, the proliferation of blinding self-centered aims and images, is itself a powerful system of energy, and most of what is often called 'will' or 'willing' belongs to this system. What counteracts the system is attention to reality inspired by, consisting of, love.

The other way in which I smell a rat here is the idea that “complexity” whatever the fuck that is, gives us two prior categories to that of love as the universal attractor to reality - that of order and chaos. Maybe. Maybe not. I participated in a podcast interview recently where I argued that most invocations of ‘complexity’ were bullshit. But you’ll be the first to know when it is published. It was a lot of fun.

Pharmaceutical Drug Regulation and Mortality: Evidence from E-cigarettes

Abstract

This study evaluates drug regulation in the United States by examining a product that was unexpectedly judicially exempted from drug regulation in 2010: e-cigarettes. We compare these effects to nicotine replacement therapy, which was not exempted. Our analysis shows that this exemption led to significant increases in e-cigarette innovation, as evidenced by patent applications. Leveraging differences in smoking rates across demographic groups prior to e-cigarette introduction, we find that from 2011 to 2019, e-cigarettes saved 677,000 life-years, or approximately 1/3 the estimated benefit of early HIV/AIDS drugs through year 2000, and increased social surplus by $8 billion annually. We demonstrate that reduced smoking is a key mechanism explaining this mortality reduction, with statistically significant smoking reductions proceeding mortality reductions by approximately 4 years.

Sweet

Heaviosity half-hour

From Brian Matthews’ introduction to Rose Boys

ROSE Boys begins on 22 August 2000 in ‘an upstairs study in Adelaide’, not far from St Peter’s Cathedral, where for the moment the bells are ‘blessedly still’. Further down the road from St Peter’s, and in sound of the bells when they are in full voice, is the Adelaide Oval, perhaps the most beautiful of Australia’s cricket grounds, and the venue for a Sheffield Shield match between South Australia and Victoria in January 1973. Forced to follow on after being 205 runs behind on the first innings, Victoria was rescued by an opening partnership of 217 between Paul Sheahan and Robert Rose, who batted for five hours to make a ‘dogged’ 94.

Reading through family records in the silence of that upstairs study, Peter Rose relives scenes from his boyhood with his brother, Robert, and their parents, Elsie and Bob (one of Collingwood’s greatest footballers); but it seems there is no escaping a truth that is as insistent as the cathedral bells when the hour turns. Too quickly, brutally, a random choice opens his brother’s scrapbook ‘at a front-page story drawn from the Melbourne Herald of 15 February 1974’—‘ROSE PARALYSED IN CAR ROLL’, runs the headline. The Australian that same day is unequivocal: ‘CRICKET, FOOTBALL STAR IS PARALYSED’.

No matter what diversions the scrapbook turns up—a riotous wake after the Magpies’ legendary 1970 Grand Final defeat; the moods of coach Jock McHale; Bob and Elsie’s courtship and marriage; flashing scenes of young Robert, the brilliant batsman and mercurial footballer—the merciless narrative to which Peter Rose has tentatively, fearfully committed himself will out. About to turn away from the scrapbook’s intolerable reminders, the pasted-in clipping about the ‘transformation’ wrought by ‘a driving accident—just another of our crashes—and a second or two in time’, Rose is brought back into the unremitting penumbra of memory, the unreachable silence of the dead and, above all, the unanswered questions the dead leave in their wake.

And so the first chapter, ‘Scrapbooks’, a skirmishing with the past—now intense and tight-lipped, now genial and indulgent—becomes a magnificent prelude to confronting again the pain that awaited the Rose boys and all their family when Robert’s Volkswagen spun off the road near Bacchus Marsh on St Valentine’s Day in 1974.

What exactly is the message of Robert Rose? One year after his death, twenty-six years after just another of our crashes, knowing the effect it had on his family and friends, and thousands of others who hardly knew him, I want to go back there, I want to examine my brother’s life and reanimate him…Here, in my Adelaide eyrie, with my documents and my pent cathedral bells, I want to examine his achievement, what he symbolised, what he gave and what he withheld, what he divulged and what he never said, as a son, as a brother, as a husband, as a mate, above all as a tragic victim of that ‘second or two in time’.

And so I hold on to the outsize scrapbook for a while longer. It is time to listen to my brother whose message, laconic but self-evident to many in his life, I somehow never fully heeded…

Again I turn to the handsome lad, the vaunted youth, the rage recruit, and will him to speak to me.

Like all fine, evocative prose, Rose’s splendid re-creation of the place and mood in which he set out on his memoir journey has echoes of, and is intensified by, other voices seeking the same truths: his fellow poet Kenneth Slessor, for example, who, willing the dead to speak to him, hears only ‘five bells coldly ringing out…the bumpkin calculus of Time’.

Rose Boys is the story of Robert Rose’s transformation from a quintessentially Australian sporting life of brilliance, promise and sheer physical energy to the confined and cribbed world of the quadriplegic. More broadly, it is the wrenching account of a family living for a quarter of a century in the sometimes tightening, sometimes loosening, never absent grip of catastrophe.

The book begins unannounced, in a brief prologue that moves with the pace and fractured logic of a dream: ‘Electric afternoon. Hiding from humanity, I drift through burnt spears and withered grass. My walk is soothing but fraught with snakes and goannas. They rustle in the flammable scrub, reminding me that anything can happen to a solitary. In the distance a minor cemetery catches the sun…A woman appears, frantic and dishevelled…’

The prologue ends inconclusively, when a small boy with ‘uncanny vision’ ‘takes pity’ on the wavering intruder and speaks to him. This dream—inchoate, compelling—resurfaces at the end of the book in the form of Peter Rose’s splendid poem ‘I Recognise My Brother in a Dream’. From the remorseless heat of the trials that Robert and the family had endured there issued at long last, shaped and graspable, the product of ‘seven years and thirty drafts’, a hard-won serenity, the pitilessly even-handed but reconciling equilibrium of art.

In contrast to the disorienting dream and the richly allusive poem, the main narrative between the two is spare and tense: ‘Robert was lying on his back, looking rather beautiful. His head was shaved. They had already drilled holes in his skull and inserted calipers attached to eight-pound weights. Robert’s head was pulled back, immovable. There was a tube in his mouth. Mum kissed him. His first words to her were, “I’m in trouble.”’

Artless on the surface—telling it how it was, you might say—this tremendously moving moment is unerringly timed from word to word, sentence to sentence, to deliver the hammer blows of disaster without breaking up under their force. Like Nick Adams in Hemingway’s story ‘Big Two-Hearted River’, who keeps panic at bay with a succession of small, deliberated tasks, Peter Rose, scarcely knowing what to feel or think, controls surges of panic and grief within tight, unadorned prose. It was just about the only way he could write it.

Rose Boys is relentless: when you think it can’t get worse for Peter and his parents and their circle, it does. When you think Robert can suffer no more, that torture upon torture must kill him, he endures, suffering before the gaze of his loyal, loving, helpless family. The telling of this story is so right that it is easy to overlook the nature of the task Rose set himself. No feelings are spared here—not the reader’s, not his own—least of all his own.

The book’s trajectory is a descent that ravages and cauterises the Roses, strong though they are, and threatens all bulwarks, structures and props. Disintegration flickers through the story with increasing certainty, and that sense of pervasive illness which afflicts tragic households becomes a sub-theme in Rose’s memoir. ‘The extreme days had begun,’ he writes in his journal, ‘days of futility, days of grief’, days of ‘volatile, ungovernable’ emotions. ‘No one was in good shape’ and at times, he says, conceding how graphically the image of Robert’s broken body commanded their thoughts and imaginations, ‘it felt as if we were all crippled.’

They had been gathered into what Susan Sontag called ‘the night-side of life…a more onerous citizenship…in the kingdom of the sick’. They would return at last from this drawn-out crepuscular gloom incalculably altered, damaged, but glimpsing a hard renewal.

For himself, Rose looks down for the last time on his brother with ‘a pang of something that would never fully dissipate—incompletion, incomprehension, rich regret…’ There seems to be no resolution available to him. Even his last-minute attempt to see the Collingwood team honour Robert is foiled by rain and confusion.

Yet this story of fractured lives, unassuageable grief and nowhere-to-turn desperation becomes, in Rose’s hands, a triumph. Though seeming, in retrospect, unrelieved—I read it at a sitting when it was first published, in 2001, and its images and episodes ghosted round me for days—the story of Robert Rose’s tragedy is both ennobled and lightened by a context that calamity cannot diminish. Friends, children and extended family populate and colour the ‘shifting text’: Bob’s parents, Bert and Millie, with ‘one cow but no fence’; Uncle Rusty, ‘a wheat-farming bachelor with a roll-your-own cough’; and the Rose family’s Nyah West home, in Elizabeth Street, ‘named after one of the little princesses but commonly known as Blowfly Flat’.

And there is Peter Rose himself, ironic, witty, ‘Thicko’ to his equally witty and ironic brother. His account effortlessly ranges across past and present, and is variously enriched by glimpses of Melbourne’s football culture, his emerging sexuality, his discovery of the depth of his fraternal love, his growth as a poet and his affection for Robert’s daughter, Salli.

Through it all there is the selfless devotion of Elsie, devastated but indomitable, resilient; and Bob, a wonderful human being, unassuming, dogged, loving. And there is Robert Rose, whose inspiring courage, lost promise, shattered body and tortured soul this great book unflinchingly documents, celebrates and gently lays to rest.

The final chapter or Peter Rose’s Rose Boys

The banner

Robert’s body was released the following morning. The death certificate followed some weeks later. The cause of death was given as sepsis, retroperitoneal infarction and quadriplegia. Quite!

I went to work that Thursday and tried to catch up. A miasma of emails confronted me. I thought about our sales conference, due to start on Monday, at which I would have to present my major titles for the year. Much remained to be done in Auckland after the recent changes. I now had twice as many authors to commission, edit, hector and pacify.

That night, the eve of the funeral, we launched Peter Porter’s Collected Poems. This was slightly ticklish because of OUP UK’s recent abandonment of its poetry list, a cavalier decision that had incensed every militant poet and headline writer in both countries. Peter had always been published by OUP UK, not by us (I produced anthologies, including one edited by him, but not slim volumes), but this distinction wasn’t widely appreciated and we found ourselves thoroughly implicated in the parent company’s clumsy schema.

The launch took place at Readings in Carlton. I was supposed to introduce our launcher, but a colleague stood in for me. I went along numbly, wanting to congratulate Peter. I stood near the exit. Most of the guests knew about Robert’s death by this stage. The men, by and large, responded differently from the women—or rather, didn’t know how to respond. Most of them stayed well away. The women seemed to know what to do inconspicuously and without effusion. Morag Fraser steered me to one side and stood beside me during the speeches, keeping an eye on me. I was grateful for her company and tact.

I left soon after the speeches and returned to St Kilda. C. flew in from Adelaide later that night. After he went to bed I sat up and worked on the eulogy. I had never written one before. In the morning—I have no idea why—I went into work to discuss the editorial consolidation of New Zealand and related changes in the office. So there I was, swapping stratagems, drafting emollient letters and press releases, a few hours before my brother’s funeral.

The mood at Crosby Drive when C. and I arrived was sombre. I read the death notices and that morning’s crop of letters. I found Mum in her bedroom and sat with her on the bed. She looked elegant and bereft. Staring at her hands, she spoke softly, a new note of desolation in her voice. She wanted to talk about her own regrets, or some of them. She felt guilty because she hadn’t acted on her latent anxiety about Robert’s swollen stomach. I told her that she and Dad had done everything they could, that they had been magnificent. Hanging there between us was the knowledge that Robert’s final year had been appalling—and so futile. After twenty-four years of anguish he had been subjected to untold misery in the place he dreaded most. What good had it done? Why hadn’t he been spared? In what way had he benefited from that pegged convalescence? Robert’s final suffering made the parting rank, like a perpetual wound.

Consolation—the theme of my eulogy, such as it was—would have to be grafted, magnified, earned.

The funeral director didn’t want us at the church until the advertised start. Mum concurred; she didn’t want to have to speak to anyone until it was over. She also dreaded the prospect of television cameras in the church, but was told that they would be placed in the choir, not up the front. For Dad—always the first person to arrive at a function—our half-hour delay was anathema. He wanted to go straight to the church, greet the mourners and be with his family. We kept inventing reasons to postpone our departure. Finally, the chauffeurs led us to the cars. We set off, only to drive around the block—wonderfully slowly. I didn’t even look at Dad.

Seven hundred people had descended on the church. It was full, as were two nearby halls. They had set up speakers for those standing outside. Many of Robert’s old teammates were there, as well as current League footballers and cricketers, and survivors from the 1940s and 1950s, who had come along to commiserate with Dad. Lou Richards wisecracked with a group of old cronies. The Collingwood board was present, led by its new president, Eddie McGuire. The board had invited everyone back to the club for a wake. Ron Barassi, who like me had tried to interest Robert in chess, arrived late, walking into the church with his amazing, loose-limbed gait. Asked on television a few weeks later if he ever cried in public, Ron said he wept that day.

Half the mourners signed memorial books. Some of the autographs are illegible, scrawled with emotion. Later, flicking through them, I recognised the name of one of Robert’s abandoners—the star of the television tribute.

On arrival we were led through a rear door into the church. We walked past the coffin. On top of it were Robert’s Collingwood guernsey and his Victorian cap. C. and I sat with my parents and Salli and Mark. We were the family now. It felt small, vulnerable. I thought how difficult it must have been for C., attending another funeral so soon after his father’s and meeting so many of my friends and relations on such a day. But I was very glad he was there.

The congregation was bizarrely quiet and expectant. It was like walking into an ominously subdued classroom. Although I tried not to look at the gathering, I was aware of a few familiar presences—Sonja and Michael Shmith; Morag beaming encouragement at me from behind a pillar; Brian Martin to our left, with three other gentlemen in wheelchairs; a few friends from OUP.

As I sat down I felt sure I wouldn’t be able to get up again and move to the lectern. My legs seemed to have dissolved. Then Tom Rose, his regulation Haileybury haircut now tinged with grey, began to speak. He too was nervous and stumbled over his opening remarks. I looked at a coterie of champions in the right transept. Lou Richards was ashen. Neil Balme, another legendary strongman, was visibly upset. Behind me, in the nave, was a formidable sadness. I sensed the pull of people’s sorrow—their deprivation, their commitment, their needfulness. I realised that we were all in the same boat and that it wouldn’t be ignominious to stammer or stall in such company.

Tom, in his cousinly, deliberate address, was eloquent. ‘We come believing that all human life is valuable,’ he declared. He extolled Robert’s qualities. ‘The gifts Rambles offered us will never be lost.’ He spoke of my parents’ devotion. ‘This too is a story of exceptional commitment that stirs and will continue to stir the heart.’ Then he touched on qualms that swarm around any death, but especially one like Robert’s. ‘Part of our grief may be regret for things left done or undone, words said or never said. Forgive us those times and ways we failed Robert and help us to forgive him for any hurt we feel he has caused us. Help us to forgive ourselves for any harm we may have caused him.’

Sonja, a stalwart friend, took exception to this, she later told me. But I didn’t.

Terry read from St John. Then it was my turn. I was determined to express my revulsion at the suffering inflicted on Robert. I described it as grotesquely cruel, like a stupid, vicious swipe from the gods. I wanted the high ceilings and elongated crosses to resound with some kind of refusal, however feeble. I spoke about Robert’s sporting career. Many in the church, I knew, were unfamiliar with his record. I drew on crucial incidents and images, some of which will be familiar to readers of this book. I cited the photograph of Robert kicking a football at the age of two, which had appeared in one newspaper that morning. I recalled the queer sound he made in his throat while dispatching imaginary balls to boundaries of the future. I reminisced about the day he took on D.K. Lillee at the MCG. Then I turned to my consolations: Robert’s closeness to Salli and my parents and his genius for friendship. Perhaps inevitably, encapsulating and doing justice to Robert’s relationship with Mum and Dad was the hardest part:

Bob and Elsie’s devotion to Robert was unqualified from day one and remained passionate and limitless, and always so intelligent and considerate of his physical and emotional needs. Robert returned that love in full. The love and mutual respect swirling around that little hospital room on Tuesday night, even as Robert slipped further and further away from us, cannot be captured in words. For this son, it has been an extraordinary education to observe this tacit and everlasting pact. Putting aside blood ties for a moment, I am left with a sense of awe and good fortune at having known these three people.

My final consolation was Robert’s own unique fortitude, his resilience, his incredible self-possession:

Virtually everyone was moved by Robert’s determination and by the uncomplaining calm with which he faced his many handicaps. It is impossible to exaggerate the difficulties that quadriplegics have to face day after day, year after year. What drew people to Robert was an awareness that here was someone who had suffered more acutely for a quarter of a century than most of us can begin to imagine. Pity never came into it. People wanted to know Robert because it was a privilege to do so. Here was someone who had looked into the abyss and had pulled back, never entertaining feelings of self-pity or futility or bitterness or desolation. They must have welled up, you would think, in private, in the dark—but if they did we never heard about them. Robert never once complained about his fate in my hearing. It was almost as if it wasn’t worth talking about…Robert was, quite simply, the bravest man I’ve ever known. In a self-regarding and complaining age—the Age of Bleating, one sometimes thinks, when a bad night at the casino brings out the stress counsellors—Robert’s courage was awesome, and exhilarating, and profoundly worth commemorating.

Naturally, I ended with a poem. Introducing Auden’s villanelle ‘If I Could Tell You’, I said: ‘As some of you know, in addition to my own sporting achievements I’m a poet’. The silence that followed was awkward and showed no sign of abating. ‘That was a joke,’ I felt obliged to add. Irony is wasted on a funeral.

Outside, a gale was blowing, battering the church, thudding on the roof. Several people mentioned this later, apropos one of Auden’s lapidary lines: ‘The winds must come from somewhere when they blow’.

Trevor Laughlin spoke next. His tribute was tender, hymn-like, Whitmanesque, each detail preceded by the phrase ‘And I remember’. Trevor reminisced about country capers, soccer lessons with Ian Botham, the night the Volkswagen’s battery caught fire—‘all the things we used to do when we were twenty and thought we were bulletproof’.

I never thought I was bulletproof.

After the committal the funeral director rounded up his pallbearers: Peter McKenna, Colin and Kevin Rose, Robert’s son-in-law, ‘Butch’ Canobie and myself. Afterwards, as we stood by the hearse, ‘Butch’ became upset. The national broadcaster chose to use this footage on the evening news service along with my Age of Bleating. I turned and watched the hearse leaving for the crematorium. Robert still had company. The police had offered to provide a motorcycle escort to Springvale.

As it pulled away, my brain began to shut down. I became incredibly vague when people spoke to me. My memory was addled. Familiar names eluded me. I was grateful to those people who stated their names as they extended their hands, sensing my plight. One or two people from the distant past teased me by asking me to identify them. An old girlfriend of Robert’s whom I hadn’t seen in years asked me who she was. I couldn’t help her. I began to introduce Michael Shmith to Jan Bassett and Andrew Demetriou. ‘It’s all right, Peter,’ said Michael, reminding me that we had all had dinner together at my place the previous Saturday. Jan, an historian, had been one of my authors since the beginning. Immaculate as ever, she was pale and quiet. Terminally ill herself, she had only five more months to live. I knew how grim that funeral must have been for her.

Several people commented on how much Robert had accomplished during his short life. Nathan Buckley told me that he hadn’t appreciated that before. He was only a baby at the time of Robert’s accident. Yet I never thought of Robert as middle-aged.

I spoke to Kate Breadmore, who was in uniform. Many of Robert’s other carers were present. Kate told me that all the Austin nurses would have attended but for the patients. Those sixty-two beds were never empty long.

Fittingly, when we reached Victoria Park, a football match was under way. This was Friday afternoon, so of course they were playing football. It was a reserves game, quite a lively affair. Saturday contests were rarities nowadays. Three months later, the seniors would play their last game at Victoria Park. Much hoopla surrounded this occasion. Dad and Lou were driven around the oval at half-time with other veterans.

We ascended to the President’s Room, zone of the toffs. Mercifully there were no speeches. Gin revived my spirits but did nothing for my scattered wits. Someone congratulated me on my ‘urology’. I introduced C. to my aunts before crossing the room to speak to Brian Martin. He told me that Robert had been like a brother to him. A man came up to me and said he was one of those who had ‘gone missing’. I’d never heard of him before. He said he was a journalist. I found it interesting that he needed to confess. I sat with C. and my friends, blissfully smoking. Never before had I been so sure of the blessing and constancy of friends.

Somewhere a photographer was studying my father—waiting for the moment. The portrait that appeared in the Age the following day was subtle and beautifully composed. Dad, unaware of the camera, moves through the nebulous company, glass in hand, slightly quizzical, looking for someone. He had pushed Robert around that room a thousand times. In the accompanying article the journalist lingers on the periphery, speaking to Brian Martin and some of the nurses. ‘These were the people who had spent more time with Robert than anyone, and their praise was uniform. Such a nice person they said. Always interested in everyone’s families.’

They even reproduced the auto-da-fé from my poem about recognising Robert. Conveniently, they printed this as straight prose, eliminating line breaks. They described it as my ‘prayer and farewell’. I didn’t care.

As we were leaving the President’s Room, the wife of one of Robert’s old team-mates stopped me on the stairs.

‘I got your joke,’ she told me.

‘Which joke?’

‘The one about you being a poet.’

None of us was ready to resume our lives, to confront the void. We decided to have dinner at a bistro in Richmond. Sonja and Michael and I had been there before, but we felt that sufficient time had elapsed for us to return. On that occasion we had cleared the restaurant with our show tunes and cigar fumes. This time we were ten. When we arrived the manager recognised Dad and shook his hand. I often wonder how he felt at midnight, for we were a boisterous group. Robert was endlessly toasted, a certain theme song lustily sung. Much wine was drunk as the anecdotes flowed. I loved hearing them for the umpteenth time. For once, I needed to hear them. Our patient waitress remarked that we looked as though we were having fun. ‘What are you celebrating?’

Janet Shaw was there with my confrère and drinking partner Craig Sherborne. Someone let slip that Janet had twice been the Australian Birdcall Champion. Elsie wanted to hear her party trick: a horse whinnying. ‘Only if you sing for us,’ said Janet. Mum declined, and prevailed. ‘You’re not really going to do it, are you?’ I cautioned Janet. ‘If Elsie wants me to …’ she replied. Her two-fingered equine whistle silenced the restaurant. It would have stopped the traffic in Manhattan.

Robert would have loved it.

The morning after the funeral I was like a zombie. At midday C. and I went to Crosby Drive to retrieve my car. My parents had gone to the MCG for a Collingwood match. Although exhausted, they felt they should be there to see the team banner, a billowy tribute to Robert. We drove into town intending to find somewhere to have lunch. On the way I played some music. Suddenly I wanted to be there when the players ran through the banner. I asked C. if he would mind taking me to the MCG. I only wanted to stay for a minute.

Huge dark clouds hung over Jolimont. We arrived long after the crowd. The fans were all inside, and the match about to start. We ran through the boggy car park as hail began to fall. Between thunderbolts I heard the crowd greet the opposing side and abuse the umpires. I waited for the louder cheer that would signal Collingwood’s arrival. There was maybe a minute to go.

I had no idea which entrance to use. Normally I had a pass, but not today. We dashed from gate to gate. Someone directed us to the paying gate. We queued with a few stragglers, thoroughly saturated. Just as we reached the cashier I heard the unmistakable roar. We turned around and trudged back to the car.

I remembered Mum’s old dream in which Robert was stranded outside the ground under a tree. I searched for that tree.

Buy the book. It’s a Text Classic and cheap as: