How the UK might have handled its grooming gangs

The way Australia did. And other things I found on my travels

How the UK might have handled grooming gangs

The way Australia handled them

Helen Andrews in Compact.

In the early 2000s, Sydney was rocked by a series of gang rapes. Victims were ordinary Australian girls, some as young as 13. The perpetrators were Muslim, mostly Lebanese and some Pakistanis. Two cases—the Skaf brothers case and the Khan brothers case—received extensive newspaper coverage, but the phenomenon was more widespread. Sexual assault rates increased 25 percent between 1996 and 2003 in Sydney, even as every other type of violent crime was declining.

The gang rapes were similar to the "grooming gangs" operating in Great Britain during the same period. The difference is that in Britain the problem was allowed to fester. Australia nipped its problem in the bud, thanks to the way its authorities handled the problem.

The first thing Australia did right was to prosecute the perpetrators vigorously and hand down long sentences. The second was refusing to shy away from the racial angle. Some voices in the media and the Muslim community wanted this aspect suppressed, but the attackers had used racial language during the assaults ("We're going to rape you, you Aussie sluts," "If a Leb wants to fuck you, you fuck them"), and judges and politicians addressed these remarks publicly...

On August 4, 2000, a 14-year-old girl was riding the train home to the Sydney suburb of Punchbowl from her after-school job when she was approached by four Lebanese teenagers. The boys tried to engage her in small talk for a few minutes before propositioning her: "Will you fuck me? Come on, you'll like it." When she told them to go away, one of them grabbed her around the neck and threatened to knock her out if she resisted. Another one put a condom on his penis and waved it in the girl's face before getting a phone call on his cell. He told the caller, "I've got a slut with me, bro, come to Punchbowl."

The girl managed to escape from the group at the Punchbowl stop and ran home to her mother, who took her to the police station...

The Skaf brothers gang—which included several unrelated friends of the brothers Bilal Skaf, 18, and Mohammed Skaf, 17—initiated most of their attacks in the same way. They would pick out a girl or a pair of girls at a train station and chat them up, offer to give them a ride, and sometimes offer marijuana as well. The girls would then be taken to a public park or a house and forced to perform sex acts before being dumped on the side of the road to make their own way home...

The first media story about immigrant gang rapes, which featured the Skaf rapes prominently, was published in July 2001 by the Sun-Herald in a Sunday front-page feature, "70 Girls Attacked by Rape Gangs: Caucasian women the targets." Media interest peaked the following year when the Skaf brothers were brought to trial and sentenced in 2002.

The story struck a chord with the public because Lebanese crime was a growing issue, and not just sexual assaults...

The police organized strike forces to deal with these problems. Task Force Gain focused on Lebanese organized crime and drug trafficking. Task Force Sayda focused on immigrant gang rapes. Some activists protested that police were unfairly targeting a single community. A drive-by at a police station in a Muslim neighborhood was committed by shooters who said they wanted to "teach the police" about hassling Lebanese youths. But the police were not deterred and these task forces led to many successful prosecutions...

One misstep by authorities came in August 2001 when the judge in a gang rape case handed down extremely lenient sentences. Four Lebanese men, the oldest of whom was 19, picked up two teenaged girls who were stranded at a train station at 1 a.m. after the line stopped running. Instead of being taken home as promised, the girls were taken to a house, menaced with a knife, and raped... Judge Megan Latham gave one of the offenders a sentence of only 18 months...

The backlash was immediate, with most of the outrage focusing on the judges claim that the girls had not been racially targeted. Six months later, the Court of Criminal Appeal declared these sentences "manifestly inadequate" and increased the boys' prison terms to 13 years and 14 years...

The Cronulla Riot

I lived in Australia for seven years, and the response most Australians gave when I asked them about the Cronulla race riot surprised me. They insisted I should consider the background before rushing to judgment. This was especially striking because, in every other respect, Australia is a more politically correct place than any place I have lived in America, even the bluest cities.

There are several reasons Australians might feel comfortable offering excuses for the Cronulla riot. No one was killed or even seriously wounded. Only a tiny fraction of the 5,000 Australians who came to Cronulla for a "Take Back the Beach" protest engaged in any violence at all. Most important, the situation at Cronulla was widely known to be so bad that some kind of pushback against the increasingly aggressive behavior of young Lebanese males on the beach was thought to be warranted...

The following are firsthand reports from Cronulla beachgoers, collected by Australian reporter Paul Sheehan in the aftermath of the riot:

"Every girl I know has been harassed or knows someone who's been harassed. It's not just young girls. I've been followed on numerous occasions. It's just constant harassment. The word 'slut' gets used all the time."

"They treat our beaches like a sleazy nightclub. They treat young women like garbage. And as soon as you say anything, they are on their mobile phones to 50 of their closest friends and their mates come down and outnumber people. If it's guys, they will beat them up. If it's girls, they will terrorize them."...

The Daily Telegraph reported on December 10 that a Lebanese man had taunted one girl, "You're not worth 55 years"—a reference to the Skaf brothers' sentence...

Violence was kept to a minimum because the police were prepared, assertive, and evenhanded. One drunk white man chased a Lebanese passerby and kicked him in the stomach. He was promptly arrested. Middle Eastern victims targeted by angry white crowds were escorted by police to safe locations...

So what was the ultimate effect of the riot? Cronulla's ethnic frictions ceased, and today it remains a pleasant seaside town. (I visited once when I lived in Sydney.) No one wants to say that violence worked. In this case, I don't think we have to say that. The crucial ingredient here was not violence but territoriality.

Every space belongs to one community or another. That community decides what norms prevail there. Other groups can be present, as long as they are just existing, but if they attempt to assert their own norms, resistance must be offered or else possession of the territory will pass to the newcomers...

The Aftermath

A 2013 Sydney Morning Herald article looking back at the Skaf case noted that the problem of immigrant gang rapes had become "virtually non-existent." The head of the New South Wales Police Sex Crimes Squad was asked by the reporter if the Skaf prosecution helped to eradicate the problem. "I would think that played a part, yes," he said. "It certainly drew a line under it."

That clean record was broken in June when four men were arrested for a six-hour-long gang rape of a Sydney teenager...

Margaret Cunneen was the crown prosecutor in both the Skaf and Khan brothers cases. In an interview with me, she notes similarities between this latest case and the earlier Sydney gang rapes, such as "depredations over many hours, with additional offenders joining in after phone contact." She says, "It may be that the lessons of a generation ago have faded."

"There were no crimes of organized sexual violence of a similar nature in the suburbs of Sydney for two decades" after the Skafs and Khans were sentenced, she says. She credits this to the meticulous work of the police investigators, media support for tough prosecutions, and the authorities' empathetic treatment of the victims. "There was some resistance in the name of political correctness," she recalls, but those objections were not heeded by her colleagues in the legal system. "Harsh penalties were sought, and imposed."

Female radicalisation: it’s different

Interesting piece from Claire Lehman

Banging drums in Columbia University's Butler Library in early May, a group of protesters shouted: "Free, free Palestine!" When campus security shut the doors of the reading room, effectively trapping the demonstrators in, their chants turned into pleas. One person tried to break through to the exit, and a scuffle broke out. "You're hurting him, stop!" a girl cried out. By the end of the occupation, 80 protesters had been arrested. Sixty-one of them were women.

The Columbia protest made national news in the U.S., but the striking gender imbalance of its participants went largely unnoticed. It shouldn't have. Whether the cause is Gaza, climate change, Black Lives Matter, or feminism, overrepresentation of young women has become the norm in progressive activism. And this shift signals a susceptibility to ideological extremism.

Women moving to the left is a global phenomenon. A 2020 study on the Extinction Rebellion environmental movement in the U.K. described it as a "highly feminised" protest culture. Surveys have found that attendance at climate demonstrations in cities around the world tends to be about 60 percent female, and recent American progressive movements—such as Black Lives Matter and the Gaza encampments—have likewise been launched and sustained by women. ...

Data published by John Burn-Murdoch in the Financial Times confirms that the shift spans continents. In South Korea, the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom, Gen Z women have shifted toward "hyper-progressive" political positions, while men in the same age cohort have held steady or moved to the right. In the U.S., according to Gallup data, women ages 18 to 30 are now 30 percentage points "more liberal" than their male peers.

There is growing awareness of how young men can be drawn into far-right extremism or misogynistic subcultures, but we in the media—and society more broadly—pay less attention to how young women become drawn into political subcultures. Indeed, the terms "radicalization" and "women" are rarely—if ever—seen together. ...

The escalating tactics of climate activism illustrate the pattern. Last year, three female members of the British climate action group Just Stop Oil, alongside two male members, were sentenced to prison for climbing onto overhead signs of a major motorway, forcing police to shut down traffic. ... The stunt created major gridlock that led to people missing medical appointments, exams, and flights. ...

Men are still engaging in radical left-wing protest, of course, with Aaron Bushnell being a salient example. But we find it easy to recognize radicalization when it happens in young men, while romanticizing or ignoring the same phenomenon in women.

Sometimes, mainstream institutions don't just overlook female extremism—they actively encourage it. ...

This dynamic is perhaps best reflected in the career of Greta Thunberg. Since she began skipping school at the age of 15 to demand action on climate change, Thunberg has been showered with encouragement and awards. ... No matter what one thinks of Thunberg's activism, it is hard to imagine a young man receiving the same level of global adulation. A "Gus" Thunberg who encouraged children to skip school would be more likely to be called in for detention than invited to the U.N.

Thunberg's trajectory illustrates a broader pattern: Radical behavior from young women is not just tolerated but actively encouraged through awards, platforms, and institutional support. This creates a feedback loop. ... "If you, as a climate activist, don't also fight for a Free Palestine and an end to colonialism and oppression all over the world," the now 22-year-old activist declared at a demonstration in Milan last year, "then you should not be able to call yourself a climate activist." This demand for ideological purity across unrelated causes is a signature move of female radicalism...

It's easy to dismiss such actions as inconsequential compared to the violence of male radicals. Women rarely engage in political assassinations or mass shootings, the way a small subset of fanatical men do. But the blocking of infrastructure and the vandalism of cultural property inflict a real toll—on the public, yes, but also on the activists themselves. ...

Still, existing studies in moral psychology and social behavior offer valuable clues about the underlying dynamics. Moral Foundations Theory, developed by the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt and colleagues, argues that human moral reasoning is built on a set of intuitive foundations: Loyalty, Authority, Care, Fairness, and Purity. A 2020 study using this framework across 67 countries found that women consistently scored higher than men on the latter three. ... These tendencies, while adaptive in many contexts, can also make young women particularly receptive to political narratives framed in terms of trauma, injustice, and moral absolutism. ...

The way young women organize their social lives compounds this vulnerability. Studies by developmental psychologist Joyce Benenson have found that female friend groups tend to be less resilient than those of males, and many women suffer from an intense fear of social exclusion. ...

Social media intensifies these cascades. When female friendship groups migrate online, superficial displays of consensus—the sharing of memes, badges, and hashtags—can feel mandatory. ...

It should come as no surprise, then, that progressive girls were the first group to suffer a major mental health decline following the mass adoption of smartphones and social media around 2012. As Haidt points out in his book, The Anxious Generation, Gen Z girls have been socialized online in a culture based on hypervigilance toward harm, accompanied by demands for moral absolutism and purity.

This represents a new form of radicalization that operates differently from its male counterpart. When ideology takes over female friendship groups, the process is less violent and more relational, driven by peer pressure, emotional reasoning, and fear of social exclusion. ... Recognizing this pattern is the first step toward protecting young women from the misguided narratives that exploit their moral sensitivity. But to change it, we must first name it.

And read Claire’s success story

Will the young live better than the old

Yes, but only once they’re old!

A good piece from E61, and one that underlines how strangely we’ve forced people to save and invest in financial assets when they’re having young families and, if they have savings should be able to invest them in housing. (And that’s before we talk about the way the flat tax on super hikes taxes on the savings of low income folks as it taxes the savings of the wealthy concessionally.)

"For the first time in the nation's history we face the stark prospect that the next generation of children will have lower living standards than their parents."

That was the claim of then-Leader of the Opposition Andrew Peacock, in February 1990. Since then, GDP per capita has more than tripled, life expectancy has risen by 8%, the number of hours of work needed to pay the rent is down 25%, and the Socceroos have qualified for the World Cup six consecutive times.

It's hardly an exaggeration to say every Australian generation worries their children will be worse off than they are. It's equally fair to say these fears have consistently proven misplaced.

In a new report released last week, "Will young Australians be better off than past generations?," e61 revisited this age-old anxiety using applied economics and microdata. ...

The simplest measure of living standards is real incomes – the purchasing power available at any given time. Here, a genuine concern emerges. Those born in 1990 are no better off than those born a decade earlier. Wages for workers under 30 have barely increased since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

And these figures only reflect gross earnings: what young Australians actually take home is increasingly under squeezed pressure, particularly due to our tax system. Recently, Jim Chalmers spoke about the need for budget sustainability to improve intergenerational equity – the current path is already threatening the intergenerational compact.

Decarbonisation in Germany: Renewables versus nuclear?

ABSTRACT Germany has one of the most ambitious energy transition policies dubbed ‘Die Energiewende’ to replace nuclear- and fossil power with renewables such as wind-, solar- and biopower. The climate gas emissions are reduced by 25% in the study period of 2002 through 2022. By triangulating available information sources, the total nominal expenditures are estimated at EUR 387 bn, and the associated subsidies are some EUR 310 bn giving a total nominal expenditures of EUR 696 bn. Alternatively, Germany could have kept the existing nuclear power in 2002 and possibly invest in new nuclear capacity. The analysis of these two alternatives shows that Germany could have reached its climate gas emission target by achieving a 73% cut in emissions on top of the achievements in 2022 and simultaneously cut the spending in half compared to Energiewende. Thus, Germany should have adopted an energy policy based on keeping and expanding nuclear power.

Rebecca Watson on publishing her first novel

A nice piece - from Vogue UK from Feb 2021.

When my debut novel, Little Scratch, went to auction at the beginning of 2019, the news, to some, was startling. I was working as an assistant at the time, and a few who knew me as that were taken aback. One expressed embarrassment at asking me to do menial tasks, even though they had been doing so for a couple of years. Nothing had changed, I was still the same, but they couldn't fathom the connection between a person who had done something and someone who was there only to respond.

"But you're an assistant?" is a reaction that sticks with me. It was said automatically without thought of how it might sound. Hierarchy is so ingrained that those below you can seem permanently so. For some, work hierarchy may be the extent of how you judge or see a person. Maybe it's easier to ask someone to do the boring jobs you'd rather avoid if you consider them that way? ...

The reaction was fitting, though, because the novel that sold was a day in the life of an unnamed young woman who works as an assistant. I had been sure that administrative office life was fertile ground for writing. I wanted to place my protagonist in a world where it could be difficult to escape, difficult to speak up, easy to be ignored, or not known as anything beyond a role. I wanted my narrator to be surrounded by people while feeling entirely isolated: a junior job in a workplace different to mine (in being cruel and detached, which mine was not) suited the ambition. Though my protagonist did not share my life, I was keen to borrow some of a world I knew: to tease and exaggerate an administrative assistant's life as a way of exploring how this could foster something more sinister.

It was perhaps inevitable that I would be interested in writing about a person at the bottom of the power chain – a place I knew well. I have had several jobs as assistants and in various long-term hospitality roles, working on the bar, as a waitress and a cleaner at a hotel. When I quit one job, my boss refused to speak to me, furious I had decided to leave, as if it was a personal betrayal – not a free choice that adhered to all contractual obligation. ...

I didn't expect, when I was writing Little Scratch, that by the time the novel was published its environment – office life – would be on hold. It was an environment I saw as inescapable. I imagined people reading the commute scene on their way to work, reading office scenes in their lunch break, and maybe recognising something in it. ...

As working life and dynamics shift during the pandemic, retail staff abuse has doubled according to the Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers (USDAW). The pandemic has brewed antagonism. But in the office, perhaps some of it has been stripped away. Maybe, in being taken away from the office, relationships have had to be assessed. For a start, assistants are not there by default. If you want their attention, you might have to remember their names. You might see the background of their home on Zoom and wonder: What is their life?

That spark of curiosity may help. Empathy and self-scrutiny is needed. I have been screamed at, groped, and patronised in various junior jobs. What has always been clear is that while some enjoy the power, others seem to genuinely believe that the divide in front of them is dictated by God, that hierarchy has a moral, qualitative value. I can only hope that the pandemic has encouraged reflection. I hope, when, in time, we return to the office, we will be more willing to bring empathy to our interactions, be keener to consider the world beyond our own. Office culture may feel distant, but it's coming back, and when it does, it needs to be different.

Chris Richardson on the super scam

Taxing the poor to help out the rich, all brought to you by my generation of ALP policies.

ONE STEP FORWARD, ONE STEP BACK …

The debate over the new tax on earnings in super accounts above $3m has generated much more heat than light

I think new tax is far from great, but I also think it indirectly sticky-tapes some of the problems from how we tax super contributions and earnings

When it is fully up and running in 2027-28, the new tax will reduce the overall generosity of the tax treatment of super by $2.3bn in that year

However, as is so often true in policy debates, we’re taking a step backwards even before we take that flawed step forwards

In just a handful of days the mandatory super guarantee will increase from 11.5% to 12%

That increases the amount of money that can go into superannuation – and hence get a lower rate of taxation

And the cost to the budget of that increase of 0.5% to 12%? It comes at an immediate cost of $1.3bn a year (via the lower tax paid on contributions), plus an eventual extra cost of $1.0bn a year (via the lower tax paid on earnings)

Yup. The $2.3bn a year in reduced tax concessions from the new tax will be pretty much exactly matched by $2.3bn a year in increased tax concessions because we’re still making the superannuation juggernaut larger

Or, to put that differently, the cost to poorer Australians of subsidising the benefits of superannuation subsidies that overwhelmingly go to richer Australians is going to stay the same

Yes, there’s going to be a flawed step forward. But not before we manage to achieve yet another flawed step backwards.

Yet the nation is only talking about one of those two steps …

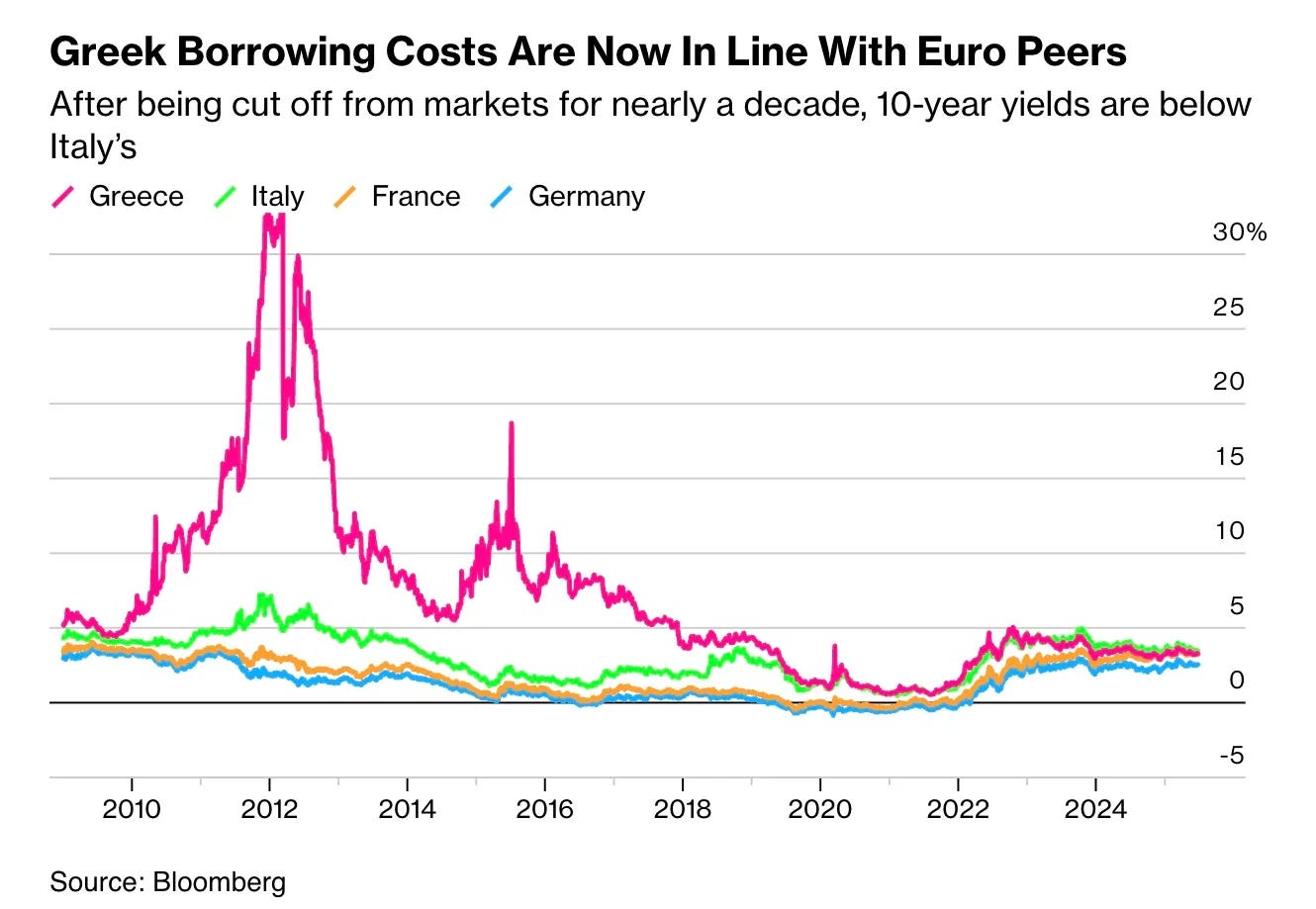

Greek bailout: ten year’s on

Above in Yanis Varoufakis on the tenth anniversary of the Greek referendum which voted ‘no’ to the European bailout. I remember thinking at the time how strange the referendum was, because the Greeks, including the left wing government Syriza were not prepared for Greece to crash out of the Euro. In other words they weren’t prepared to go through with the default. So voting ‘no’ was a bit like trying to vote oneself a more generous bailout. Which doesn’t make a lot of sense. If those giving you a bailou won’t give you better terms showing them that over 60% of your populace would like better terms doesn’t seem to me to add up to much.

And the thing is that one of the big reasons the Government wanted to stay within the Eurozone was that their constituents were strongly in favour of retaining the Euro. And having some familiarity with what Greeks think of their government, it occurred to me that, for all their resentment of the Germans, they’d rather they were running their monetary system than their own elites. And that’s what transpired.

Without knowing enough to be confident of endorsing either side, below Simon Nixon gives a contrary view, and explains some things to be optimistic about after all that pain.

Last week marked the 10th anniversary of an event that many would rather forget: Greece's referendum on whether to accept the bailout package as an exit from its debt crisis... This was the defining moment, when the young radical left-wing prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, led a defiant campaign against the deal.

Many assumed that the referendum result would lead to Greece's exit from the euro. Instead, Tsirpas fired Yannis Varoufakis, his clueless finance minister who was chief architect of the government's ruinous brinkmanship, and agreed to take the bailout...

The Deal's Hidden Benefits

That said, I argued at the time that the deal was much better than was commonly recognised... But it also provided some extraordinarily cheap, fixed-rate concessionary financing which would over time provide a form of substantial debt relief...

Above all, reforms to the public sector required by creditors to put debt on a long-term sustainable footing were desperately needed. Greece in 2009 at the start of the crisis was a semi-modern state, with a vastly bloated public sector, a completely unaffordable pension system that had been used as a general purpose welfare system, and an economy rife with corruption and clientelism.

Vindicated Recovery

A decade on, that optimism appears vindicated... Debt has fallen from a peak of 207 percent of GDP to 153 percent at the end of last year and is forecast to fall to 146 percent this year. Unemployment has fallen from 27 percent to a 17-year low of 7.9 percent. The country's 10 year bonds now trade on a yield of just 3.3 percent, lower even than Britain and the tightest premium over German bunds since 2008. Greece's decision to stay in the euro has been entirely vindicated.

Persistent Challenges

Nonetheless, not all is quite as well as it seems. Much of the growth has come from tourism, with other sectors not performing well... Wages remain well below 2015 levels in real terms...

Most worryingly, there are signs of reform fatigue amid a paralysed and polarised political system. Kyrios Mitsotakis, the prime minister since 2019, won a comfortable majority in 2023 but his government has since become embroiled in a series of corruption scandals, some of which have involved his family and advisers, that has sapped his authority. In recent trips to Greece, I heard frequent complaints that the old clientelism is returning... I even heard business leaders wondering if it might not be for the best if Tsipras, who is mulling a comeback, were to return. That is not something I could have predicted 10 years ago.

Fan vaulting

It’s always amazed me that this style of vaulting was popular for such a short period of time - corresponding to the high renaissance at the turn of the sixteenth century. There are only a few really good examples of it. This being one - built in the same year the Mona Lisa was painted and while Michelangelo was hard at work on the David. (Then there’s the ceiling of the chapel at King's College Cambridge which was being built when Michelangelo was lying upside down 20 metres above ground in the Sistine Chapel. Nice work if you can do it.)

More Weird Medieval Guys

The CIA: coming for a regime near you

I enjoyed this review.

We are told that the Central Intelligence Agency is an institution born of war. Its founding myth begins not on the beaches of Normandy, through the exploits of William (Bill) Donovan and the short-lived Office of Strategic Services. In this conventional narrative, the CIA is a Cold War necessity, improvised in 1947, briefly disoriented in the 1990s, then reawakened on September 12, 2001.

Hugh Wilford's The CIA: An Imperial History is a thorough and measured rejection of that mythology. His thesis is disarmingly simple and historically urgent: the CIA, from its inception, was not merely an instrument of American security, it was, in method, personnel, and consequence, an imperial organ. Not metaphorically. Literally...

American Intelligence as Imperial Continuity

Wilford positions the CIA not as a historical aberration or a temporary wartime adaptation, but as a logical inheritor of Western colonial intelligence traditions. British MI5 and MI6, along with the secret services of other European imperial powers, offer direct genealogical and methodological antecedents. Figures like Rudyard Kipling, Marshal Lyautey, and T. E. Lawrence (a.k.a. Lawrence of Arabia) are shown to have shaped the CIA's psychic and operational architecture...

Missionaries of the CIA's Founding Class

Wilford's attention to class and culture is one of the book's great strengths. He opens not with a coup or a double agent but with Sherman Kent, the Yale historian and founder of the CIA's analytic arm, who insisted intelligence work should emulate the scientific method. But Kent, and those like him, were not just technocrats. They were often "Groton and Harvard men," part of a class steeped in British colonial literature, Protestant paternalism, and an inherited belief in Anglo-Saxon stewardship...

Regime Change as Ritual

The case studies in Wilford's first section, Operation Ajax in Iran, Lansdale in Vietnam, Roosevelt in the Middle East, are not merely recounted but theorized. Kermit Roosevelt Jr's coup in Tehran is dissected not as an aberration but as a model: covert, rapid, elite-focused, and media-manipulated...

The Boomerang Home

Empire, Wilford powerfully argues, does not remain abroad. He frames the CIA as a boomerang institution, whose overseas tactics inevitably return to reshape the homeland. Surveillance practices honed in the colonial Philippines were repurposed for domestic use against leftist and Black "subversives". During the Cold War, this boomerang effect intensified through programs like Operation MHCHAOS, which applied countersubversion tactics to the American anti-war movement...

Narrative as Strategy

One of Wilford's quiet provocations is that the CIA, for all its covert actions and paramilitary bravado, was ultimately a storytelling machine. Under Cord Meyer's leadership, the International Organizations Division ran covert programs that supported groups like the Congress for Cultural Freedom to ensure that liberal, anti-communist voices dominated global intellectual life...

The Global War on Terror as Neo-Imperial Revival

The post-9/11 CIA did not reinvent itself so much as dust off the colonial playbook. Extraordinary rendition, black sites, and "enhanced interrogation techniques" were not innovations; they were returns. As Wilford shows, waterboarding was already practiced as the "water cure" in the Philippines during the American occupation a century earlier...

Understanding the Empire We Deny

The CIA: An Imperial History is not a polemic. It is a work of quiet dismantling. Wilford takes apart the comforting myth of American innocence and replaces it with something harder, more disquieting, and more useful. His research does not reduce the CIA to an evil empire, nor does it excuse its excesses as historical necessities. Instead, it demands a recognition: that the story of American intelligence is also the story of empire.

Wilford achieves something rare: he reframes the central institution of the American security state not as a mystery to be solved but as a history to be understood. And he does so with the precision of an analyst and the clarity of the best storyteller.

The CIA: An Imperial History is not merely important. It is a benchmark against which all future histories of intelligence agencies must be measured.

Leunig

I was looking for the Leunig cartoon about the tattooist you see below to show a friend. And I came upon a fine cache of Leunig cartoons. So here are some of them.

AI Accellerationism

From Compact.

At the height of the Cold War, the conservative magazine National Review, sold buttons that read "Don't immanentize the eschaton!" The catchphrase, adapted from the philosopher Eric Voegelin, enjoined Americans to look askance at utopian promises and grand projects of social transformation.

Half a century later, the Republican Party has placed itself at the forefront of a project aimed at immanentizing a digital eschaton. On May 22, 2025, the GOP-controlled House of Representatives quietly voted to bar US states from regulating artificial intelligence. Buried in the "Big Beautiful Bill" was a 10-year moratorium on enforcing state AI regulations... If the clause survives the Senate, these will be blocked by the federal government with hardly any congressional debate.

This embrace of unregulated AI points to an intellectual contradiction on the contemporary right. While some conservatives are skeptical of AI, the Tech Right has in its ranks a number of AI millenarians who assure us that accelerating technological progress will bring about heaven on earth... Sam Altman of OpenAI, who earlier this year joined forces with President Trump to launch the $500 billion Stargate Initiative, promises to build a "magic intelligence in the sky."

Even more radical ideas are being floated by AI successionists, who go so far as to propose that AI should replace humanity altogether... Former Google CEO Larry Page has likewise claimed that the replacement of humans with artificial intelligence "would simply be the next stage of evolution."

A conservative disposition should—to say the least—incline one to be wary of this sort of secular eschatology. Conservative sage Russell Kirk cautioned against embracing the "cult of Progress" that venerates the new simply because of its novelty. The philosopher Michael Oakeshott similarly reminded conservatives to prefer "present laughter to utopian bliss." What would these thinkers say to today's GOP, which is coming to the aid of technologists who openly pursue millenarian goals?

At current rates, AI models are doubling in scale roughly every nine months. Under the moratorium in the "Big Beautiful Bill," states will have no power to touch systems potentially a thousand times more potent than GPT-4 until at least 2035. And conservatives should know better than anyone the risks of leaving the power to respond politically to this evolving situation solely in the hands of the federal government.

Republicans rightfully fear the red-tape and regulatory capture that often follow broad interventions into the market, but they have always been willing to support targeted regulations on emerging technologies in the interest of prudence... President Trump signed the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act which expanded CFIUS's authority to block deals involving "critical technologies," imposing prudent restrictions without enfeebling the entire sector.

Even Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic, one of the leading AI companies, has called the moratorium "far too blunt an instrument," because "AI is advancing too head-spinningly fast." What does it mean that the Republican Party's AI stance is more extreme than Amodei's?

Congress could easily correct course by rewriting the clause so the moratorium expires after two years. If AI progress really moves as quickly as its boosters claim—and as some of its detractors fear—lawmakers should be forced to keep pace. Republicans can preserve corporate freedoms and keep America's lead in AI, while also addressing real concerns about safety.

But slowing the reckless march toward the digital eschaton also requires that traditional conservatives reclaim their own heritage of endorsing measured and incremental progress guided by tradition... "change is constant; the great question is not whether we resist the inevitable, but whether that change is carried out in deference to the manners, the customs, the laws, and the traditions of a people." These may be old words, but they are perfectly suited to the age of artificial intelligence.

The new Rodney Dangerfield?

Maybe not, but some very funny lines

Very cool

Australia’s modernist women artists

I was in a bookshop the other day and happened upon a delicious looking large volume with lots of pictures of Australia's early 20th century women modernist artists.

It seemed to be an unusual book. It was hard to work out who the author was but the pictures were lovely and it had a page of sponsors at the back. Of course it was a book of an exhibition and I was pleased to see that I had not missed the exhibition. It is coming up around Australia in the coming months. Here is an article about it. I found in the Saturday paper and some wonderful Australian women modernist paintings (though not necessarily paintings that are in the exhibition).

"Australia is a fine place in which to think ... you do not get bothered with foolish new ideas," Margaret Preston quipped in an essay for The Home magazine in 1923. By then, Preston was a leading Australian modernist and had twice lived in Europe. Exposed to international ideas, Preston returned converted and set about dragging Australia into the new age.

Dangerously Modern lauds 50 women artists who underwent some version of that transformation. Not all were as successful as Preston, but each has made a contribution to this country's sometimes reluctant advancement. A collaboration between the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA) and the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Dangerously Modern draws on the strengths of both institutions. Meticulously researched, it brings together an extraordinary range of work.

Curators Elle Freak, Tracey Lock and Wayne Tunnicliffe have taken an expansive view of modernity, starting the exhibition in 1890, giving themselves ample room to examine periods of development. The journey begins in a wallpapered Victorian drawing room. We are met by the startling miniatures of Justine Kong Sing, who had success in her lifetime but whose work has suffered from art-historical neglect. Nearby, Edith Collier's Girl Sitting on a Bed (1917-18) looks on, a rare surviving nude by this artist whose more daring paintings were destroyed by her father on her return to Whanganui, Aotearoa New Zealand. This is the first chance to see Collier's work in Australia...

There are plenty of household names here, too: Dorrit Black, Stella Bowen, Grace Cossington Smith, Bessie Davidson, Nora Heysen and Thea Proctor. For these women, modernism was not simply an art movement: it was a social movement promising self-determination and self-authorship. They followed that current to Europe and drew from it. In many cases, they were vital contributors to its energy. While some returned charged, others chose to stay.

Among the latter was Agnes Goodsir, who settled in Paris. Her magnetic portraits are suffused with a frank beauty. Those here are mostly of her partner, Rachel Dunn ("Cherry"), reflecting this show's interest in personal narratives. There's a lovely through-line from Goodsir's private Woman Reading (1915) to Hilda Rix Nicholas's bold, public Une Australienne (1926). We're offered insight into not just the expansion of modern art but the development of a modern sense of self.

Bessie Davidson also remained in Paris, where she lived with her partner Marguerite Leroy and was celebrated, exhibiting until her death in 1965. Her travelling paintbox, donated to AGSA in 2018 by a goddaughter, is normally on display in the Elder Wing. It's moving to see it here, in a room featuring some of her most fully realised work.

Davidson's interiors are exuberant, dreamy evocations of intimacies, of possible lives. There is an air of private liberation: the unmade bed, the figure of her lover in the mirror, the glorious light. As with Goodsir's portraits or Janet Cumbrae Stewart's softly glowing The Chinese Coat (1919), they resonate with queer power...

While some, like Davidson, were able to live independently, others struggled financially. Bowen's life was precarious, profoundly unsettled. Kong Sing saved up to go to Europe, working as a governess for years. She got there at the age of 43.

War had a transformative influence. Hilda Rix Nicholas's moving battlefield scene, These gave the world away (1917), was made after her husband of only a few weeks was killed at the Somme. There are few depictions of violence. Instead we have Cossington Smith's post-impressionist The sock knitter (1915) or Collier's Serviceman in attic studio (1917-18), likely a portrait of her brother. Preston and Gladys Reynell made use of their ceramics skills in rehabilitation workshops for the wounded. Colours dim, distressing scenes appear. New forms arise from the emotional necessity of a changing world...

The welcome focus on development offers insight into these artists' technical journeys. In a rare treat, three scenes of the French village of Mirmande hang side by side. Painted at the same workshop in 1928 by Dorrit Black, Grace Crowley and Anne Dangar, the cubist influence comes through. Each tackles the formal challenge in her own way. It's a window into the complex relationship between technique and voice, with the added strength of shared experience.

While there's a surfeit of beauty here, it's difficult to fight back anger at the stories of neglect. We know that for every artist here there are others who never found an audience, who gave up on their practice, or whose archive lacked the posthumous assistance of a canny niece or godchild. Agnes Goodsir's partner sent her paintings to Australia after her death. Australia by then had the good sense to keep them...

In the final room, two familiar self-portraits beckon. Stella Bowen's Self-portrait (1928), made after her separation from Ford Madox Ford, is amplified in the flesh. This is an image of blazing intensity, pain and defiance. Across the room, Nora Heysen gazes more contemplatively from a domestic scene in Down and out in London (1937). Soon she will return home and forge an extraordinary career: the first woman to win the Archibald Prize, the first female Australian war artist. For now, she is bathed in London's pale light, softened by the fresh risk of loosened brushwork.

Like so many of the works here, these paintings hum with courage. Dangerously Modern is electric.

I thought I’d seen all the Monty Python sketches: but I was wrong

Heaviosity half-hour

Joseph Heath on the fragility of cooperation

I really enjoyed reading this piece because it addressed issues I’ve pondered a lot and did so in a way that I was sympathetic to. On the other hand, I disagreed with some of its base premises and thus, aspects of its method.

I don’t like using the natural sciences as the template for thinking about society, but here I think the use of Newton to explain what he means by “explanatory inversion” works pretty well at least at the outset of his exposition. He likens the way in which Newton’s paradigm displaced the old idea suggested by our commonsense (and Aristotle) that motion requires a mover and its inversion into the idea that only changes in motion require some special explanation.

His first analogy in social sciences works fairly well - that commonsense requires crime to be explained whereas he argues Durkheim showed that our remarkable law-abidingness, well beyond our material interests is the thing that needs explanation. I could quibble with this. But I needn’t because his second example is the idea that we used to take the assertion of people’s common interest to be an explanation for their acting in concert whereas we now understand that their common interest doesn’t of itself overcome the free-rider problem. People with common interests can nevertheless free ride of others’ organisation without contributing themselves. Mancur Olsen made his reputation making this point. It was obvious, but often ignored.

Fair enough, but the current craze for explaining everything in terms of game theory is, in my opinion, not much more than that - a craze. It can be useful, but it’s often not particularly helpful (as the example of our law-abidingness above suggests). So I think it’s way too sweeping for our author to claim that “since non-cooperation is the default mode of social interaction, failures of cooperation require no special explanation, while successful cooperation is what needs to be explained.” My own way of putting this is that all social institutions are entanglements of cooperation and competition.

But that’s mainly a quibble in this context because Heath’s focus is where it should be I think - on the ways in which social justice and cooperation can be in tension. That’s a big deal, because we don’t normally discuss that tension and formulate our goals in those terms. Observing that, I agree with James Burnham that nine tenths of political discourse amounts to little more than wish fulfillment. So I found the essay below compelling. His central conviction?

… although justice is desirable, cooperation is difficult.

Introduction

One of the clearest points of demarcation between specialist discourses and everyday commentary and debate is that the former are often structured by what might be thought of as “explanatory inversions.” These arise as a consequence of discoveries or theoretical insights that change, not our specific explanations of events, but rather our fundamental sense of what needs to be explained. A simple example would be the development of the principle of inertia in our understanding of physical motion. Common sense tells us that objects in motion have a tendency to come to rest, and so in order to keep them moving there must be a constant application of force (hence Aristotle’s principle, “No motion without a mover”). Isaac Newton’s first law of motion inverted this, by claiming that the tendency of objects in motion is to continue moving until something stops them. Common sense is wrong on this point, because we are fooled by a set of invisible forces – gravity, friction, air resistance – that act upon the objects we are most familiar with. If instead we accept Newton’s suggestion, it is not just our understanding of the fundamental properties of matter that changes; our sense of what needs to be explained in physical systems changes. Most importantly, motion no longer needs to be explained, it is only changes in direction or velocity of motion that need to be explained. As a result, the entire approach to physical science is transformed, as scientists wind up focusing on questions that are quite different from those that common sense tells us are in need of response.

These explanatory inversions are perhaps the greatest source of miscommunication and misunderstanding between specialists and members of the general public. The challenge that they create is fairly obvious. It is possible to have productive disagreements and debate among people despite significant differences of opinion over many questions. But the conceptual divide created by an explanatory inversion can be quite difficult to talk across, because those who find themselves on either side of it are seldom even asking the same questions or trying to understand the same things. From the perspective of the public, the stance taken by specialists is often perceived as elitist, since those who have accepted the explanatory inversion usually become interested in talking only to others who “get it,” or who understand what the correct questions and problems are. Furthermore, they often have become so comfortable with their way of framing the issues that they forget how unobvious it can be to others and so treat those who fail to grasp it as mentally infirm. At best they may recommend remedial education, which does little to diminish the charge of elitism.

The frictions that may result from the gap between the public and the specialist perspective are a well-known source of hostility toward the physical sciences (particularly evolutionary theory), but they have the potential to become even more explosive when they involve the social sciences. The latter are, of course, the subject of more scepticism across the board, particularly in their claim to have produced a useful or reproducible body of knowledge. Whatever one thinks about this broader question, however, the social sciences have also produced important explanatory inversions. Perhaps the clearest example involves the concept of social deviance in criminology. Common sense tells us that most people, most of the time, obey the law. Crime is an anomaly, and as such, stands in need of explanation. Common sense provides us with a wealth of explanations, which seek to identify the motives that impel people toward criminal acts. But if one stops to examine these motives, as social scientists began to do, the most striking thing about them is how ordinary and ubiquitous they are. For every angry person who commits an assault or greedy person who steals from others, there are hundreds of equally angry, equally greedy people who refrain from doing so. This is what prompted the realization, articulated in the late nineteenth century by Émile Durkheim, that it is not crime that cries out for explanation, but rather law-abidingness. Common sense is wrong on this point because we are all reasonably well-socialized adults, living in a well-ordered society, and so we take for granted the institutional arrangements that secure our compliance with the rules. But the underlying mechanisms are ones that we do not really understand, as a result of which it is difficult to explain why more people do not break the law more often (since it is so often in their interest to do so). Again, there is an explanatory inversion at work, because of the change in our understanding of what needs to be explained.

A similar explanatory inversion has taken place in our understanding of human cooperation. Common sense tells us that if a group of individuals have a shared interest in achieving some goal, it is natural that they will band together to perform the actions needed to realize that outcome. Thus it is natural to assume that, absent some external impediment, interest groups will be disposed to pursue their interests, corporations will pursue their corporate interests, classes will advance their class interests, nations will act in their national interests, and so on. One of the most significant achievements of twentieth-century social science was the realization that such cooperative action is actually more mysterious than it might initially appear. Groups often find themselves caught in what are now known as “collective action problems,” where, despite having a common interest in achieving some outcome, no individual in the group has an adequate incentive to perform the actions needed to achieve that outcome, as a result of which the group as a whole will fail to act in its collective interest. And so, as Thomas Schelling put it, the default structure of social interaction lacks any mechanism that “attunes individual responses to some collective accomplishment.”1 It is not failures of cooperation that need to be explained, but rather successful collective action. Common sense is wrong on this point, because we all have the experience of being able to enter into cooperative relations with one another with relative ease. The analysis of collective action problems does not contradict this, it merely gives rise to an explanatory inversion. It suggests that the failure to advance collective goals is the default outcome, and cooperation is what cries out for explanation.

This insight was prefigured in earlier work. Thomas Hobbes’s characterization of the state of nature, for example, contained a long list of collective accomplishments that individuals could not be expected to achieve if they just did whatever came most naturally to them. Economists had similarly noted a number of “public goods” that markets and private contracting failed to provide. What the story of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, along with the game-theoretic model that accompanied it, did was to drive home the full generality of the problem.2 Again, the point is not that cooperation is impossible – people obviously cooperate with one another all the time. The point is that, since non-cooperation is the default mode of social interaction, failures of cooperation require no special explanation, while successful cooperation is what needs to be explained. Merely pointing out that it is in our interest to cooperate does not discharge the explanatory burden.

Like most explanatory inversions, this insight about cooperation has driven a wedge between certain specialist and non-specialist discourses. Nowhere is this more apparent than in our thinking about social justice. The latter term is often used to draw a distinction between the “formal” type of justice ensured by courts and the more “substantive” conception of justice that deals with what individuals actually wind up receiving, in the form of income, status, health, leisure, and other “good things in life.” The most important principle of justice in this domain is equality, and so the centrepiece of any account of social justice will be some conception of distributive justice.

The common sense way of thinking about distributive justice is to treat it like a “cutting the cake” division problem. You have some good, like a cake, and a bunch of people who all want as much as possible, and so the question becomes simply how to divide it among them. The problem with applying this view to society is that the goods that are subject to distribution by a conception of justice do not suddenly appear out of nowhere, the way that a cake does at a birthday party. They are the product of an ongoing system of cooperation. This cooperation is, in turn, difficult to achieve, often requiring a great deal of bargaining and compromise. As a result, it is difficult to apply principles of distributive justice to the outcome without knowing some of the backstory, about how that outcome came to be. It is equally difficult to say anything in a prescriptive vein about whether the outcome should be adjusted, without knowing a great deal more about how this will affect the underlying system of cooperation that produced those results. Trade-offs can easily arise if a particular scheme of redistribution can be expected to impair the effectiveness or stability of the system of cooperation.

An additional layer of complexity is added by the fact that systems of cooperation always have at their core a voluntary element. Although coercion can often be employed to extend the system of cooperation, there is no such thing as a perfect tyranny, or a social system that relies entirely upon coercion to secure compliance. At some level, people must be willing to play along in order for the social structure to be sustainable. A large part of their willingness to play along, however, will be based upon their acceptance of the justice of the overall arrangement, along with their specific place in it. So not only does the need to secure cooperation impose constraints on our conceptions of social justice; considerations of social justice also constrain our ability to institutionalize various schemes of cooperation.

As a result, even though it offends a certain political sensibility to say it, there is a gap between expert and public discourse on questions of social justice, because of the complex relationship between cooperation and principles of distributive justice. The chapters collected in this volume all explore issues that arise at this juncture. I take as my point of departure the basic framework of the most widely shared contemporary conception of justice among political philosophers, the view that is often referred to as liberal egalitarianism. This view can be traced back to arguments made by John Rawls in A Theory of Justice. And yet, even though Rawls described society as a “cooperative venture for mutual advantage,” and “an ongoing scheme of fair cooperation over time,” later theorists have varied considerably in their willingness to take seriously this aspect of Rawls’s view.3 His suggestion was that justice be thought of not in the image of divine law, as a set of cosmic principles that apply everywhere and at all times, but that it be seen rather as arising endogenously out of various schemes of cooperation, both constraining and enabling their formation. This is, in my opinion, his best and most important idea, and the papers in this collection all attempt to extend and apply it in one way or another.

If one could summarize my central conviction on this topic in one phrase, it would be that, although justice is desirable, cooperation is difficult. People have to be persuaded, cajoled, enticed, threatened, reminded, and rewarded in order to get them to do their part. Failures of cooperation are ubiquitous. Successful large-scale cooperation is the exception, not the rule. As a result, our capacity to achieve justice in this world is severely constrained by our limited capacity to organize successful systems of cooperation. This should not diminish our commitment to ideals of justice, or make us overly eager to accept compromise. What it should do, instead, is make us extremely alert to the opportunities that present themselves to improve the achieved level of justice of our society, because they do not arise all that often. It should also make us wary of wasting too much time speculating about utopian arrangements that could never be effectively institutionalized.

Each of the six papers collected here deals with a different normative question. In each, I wind up defending a position that differs from the one that would follow from a naive application of principles of social justice. This is not because I disagree with those principles – on the contrary, I start from the exact same egalitarian premises as those whose views I criticize. The difference is that I worry a great deal more than they do about the difficulty of achieving cooperative outcomes, and therefore I modulate the application of those principles in recognition of these difficulties. Thus the view that I defend, sometimes described as “left Hobbesian,” insists on evaluating the justice or injustice of any social arrangement through the explanatory inversion that sees cooperation as a fragile accomplishment. The results may appear contrarian, which in a certain sense they are. I would like to think that they are not merely contrarian, but that they arise in a more principled fashion, as a consequence of the explanatory inversion brought about by a modern understanding of the relationship between cooperation and principles of social justice.

The basic structure of my analysis of cooperation is laid out most clearly in chapter 1, “On the Scalability of Cooperative Structures,” which is both an extended commentary on G.A. Cohen’s argument for socialism and an attempt to articulate a major constraint that human systems of cooperation are subject to. Having formulated an abstract principle of equality, then shown how it can be realized in small group interactions, Cohen goes on to claim that this demonstrates the desirability of a socialist organization of the economy.4 The only question that remains is one of feasibility: how do we “scale up” the system from a small group to a complex modern economy? Intuitively, we can all understand the idea. And yet the question of why certain sorts of cooperative arrangements are more or less difficult to scale up (i.e., to expand the number of cooperating participants) is seldom posed directly, much less answered. Thus my central objective in the paper is to present an analysis and general way of thinking about institutional scale. A consequence of this analysis, however, is that one cannot posit normative ideals that are independent of the particular scale at which they are to be realized.

The second chapter, “Why Profit Is Not the Problem,” is similarly concerned with debates over the feasibility of socialism. A certain fraction of the outrage over the injustices of capitalism stems from a failure to appreciate how difficult the task is that it accomplishes (which is to institutionalize a very, very large-scale division of labour). Another large fraction is due to a lack of understanding of the particular way that markets achieve cooperative outcomes, which is not directly, by requiring individuals to act cooperatively, but rather indirectly, by placing them in a staged competition with one another. As a result, socialists have a tendency to propose alternatives to capitalism, or else improvements, that could never be institutionalized. This shows up repeatedly among those for whom the moral case against capitalism involves denouncing the evils of profit. I try to show why profit cannot be the problem, because any feasible socialist reorganization of the economy would also have to rely on profit as an organizational objective.

I switch gears somewhat in chapter 3, “Egalitarianism and Status Hierarchy,” in order to consider an issue that has not been given sufficient attention by egalitarians, particularly those who are concerned about distributive justice. There is widespread recognition that the attempt to realize equality occurs against significant background inequality. Much of it is socially produced, but some of it is “natural,” in the sense that it involves different capacities and propensities that individuals are born with. Thus egalitarians have worried a great deal about what to do with individuals with limited “talent.” What I focus on here, by contrast, is the socially produced form of inequality conventionally referred to as status inequality. Egalitarians over the years have engaged in much wishful thinking about the possibility of abolishing this form of inequality. I begin therefore by reviewing some of the reasons for thinking that it will never be eliminated. This then raises a number of questions for egalitarians: first about how to situate the phenomenon of status inequality with respect to an egalitarian theory of justice, and then what to do about it, under the assumption that it cannot simply be abolished. These are both very basic questions, neither of which has been dealt with adequately in the philosophical literature. The second question is also very difficult to answer. Thus the central ambition of the chapter, apart from broaching the issue and offering some preliminary clarifications, is to suggest that egalitarians should be a great deal more troubled by the persistence of status inequality than they are.

Closely related to the phenomenon of status is that of stigmatization. This term is often used by academics in a way that conveys their own disapproval, as though it were always wrong to stigmatize others. The reality is a bit more complicated, in that condemnation is usually reserved for cases in which the stigma is associated with unchosen traits. With chosen traits, by contrast, there is less hesitation in applying stigma, especially if the behaviour is injurious to others. What I am interested in, in chapter 4, “A Defence of Stigmatization,” is a class of cases in which the stigmatization of behaviour is controversial, despite the fact that the behaviour is clearly chosen, or subject to voluntary control. The most interesting cases involve acts that are self-destructive or self-undermining, where the perpetration involves some kind of self-control failure. One of the claims I have made, over the years, is that self-control should be seen not as a purely private matter, but as an achievement that often involves the cooperation of others. One way that people help one another is by helping each other to avoid self-control failures. Stigmatization can be an important element of this system. Thus I offer a qualified defence of stigmatization, on the grounds that de-stigmatization can exacerbate self-control failure and therefore undermine an important system of cooperation.

In chapter 5, “A Unified Theory of Border Control and Reasonable Accommodation,” I turn to two questions that have been the subject of extensive debate in recent political philosophy: migration and multiculturalism. The first involves the question of what right states have to exclude prospective immigrants, while the second asks what accommodations must be made for those who are admitted. These two issues are usually dealt with separately in the philosophical literature, and so the most obvious contribution of this paper is that I deal with them jointly, using a shared normative framework. That framework is based on a single idea, which is that the economy must be understood as a system of cooperation. What migrants are asking for is not a change of scenery, but rather for admission to a successful cooperative scheme. The question of accommodation concerns how that system must be changed, or not changed, in order to incorporate these new members. Thus the idea of social cooperation provides basic orientation for thinking about both questions.

In the final chapter, “Two Dilemmas for US Race Relations,” I discuss race relations in the United States. The baseline perspective I adopt, which informs the entire discussion, is that social integration in complex societies does not arise spontaneously. It is difficult to achieve. The presence of highly salient group differences within the society makes it even more challenging. As a result, there are few successful models of pluralistic integration. What one sees, looking around the world, are a large number of minor variations on the two or three basic strategies that work. The reason that the problem of black-white race relations in the United States never goes away is that Americans have been attempting to achieve a model of integration that does not fit into any of the standard templates. Thus my first objective is to encourage Americans to look at this problem from a more comparative perspective, in order to see why their approach to the problem has had so little success. My second objective is to articulate a set of dilemmas that prevent Americans from adopting one of the standard models. This is not offered in the expectation that it will make much difference to the situation in the United States. It is provided primarily as a cautionary lesson for non-Americans, especially Canadians, who have been tempted to reformulate many of the issues that have traditionally been dealt with under the rubric of multiculturalism into the American language of race (through the racialization of ethnic differences). This is puzzling on multiple levels, the most obvious being that it takes the conceptual framework associated with a policy that has a proven track record of failure and substitutes it for one that has a reasonable record of success.

NOTES

1 Thomas Schelling, Micromotives and Macrobehavior (New York: W.W. Norton, 1978), 32.

2 Russell Hardin, Collective Action (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982).

3 John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, rev. ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 4; Rawls, Justice as Fairness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 54.

4 G.A. Cohen, Why Not Socialism? (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009).

Yep. The rapes and violence seem to happen when a new group wants to assert control over a territory. Just like we indigenous British have been doing cnstantly foir 237 years now on this continent.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯