Competitive or rent-seeking oligarchy: The coming global battle

And other things I found on my travels

Greg Smith on the coming global struggle

I’ve known Greg Smith since 1981 when I first worked for John Button and Greg would visit our office from time to time. Greg was the Treasury’s go-to man on tax and a decade or two on was one of the members of the Henry Review into tax. In any event a friend of his prevailed upon him some months ago to present his ideas to a larger group which gathered in Melbourne in August last year to hear his thoughts on what our country wasn’t talking about. Then we did it again on Monday of this week. And what we heard was well thought out, deeply compelling and scary. I thought more people should hear from him and so have just recorded this conversation. I strongly recommend you check it out. If you prefer just the audio, you can find it here.

Quick: let’s not talk about what we need to do

There are coming elections in Australia and Canada and the world has changed. It’s a world in which we should be tightening our belts to say the very least. But no politician from a major party can afford to say so. Why? Because in electoral democracy, your opponent would immediately seek to portray a version of reality in which these hard truths are softened. We can afford those tax cuts because we’ll reduce waste/work harder/spearhead productivity growth and so on.

And so we repeat the mistakes the democracies made in the 1930s. It’s a striking fact that when the suffering came, those countries in the greatest crisis like the UK called a truce between the major parties and established national governments. It was one of the reasons Churchill resented Australia that it had the temerity to keep electoral democracy going in wartime.

I think we could do some things that would help with this, but I’ve not had time to write them up. I hope to do so by next week.

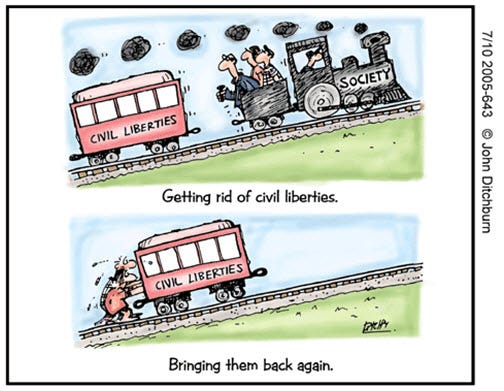

Lockdowns and liberty

Reading the article below this one about the legal nuts and bolts of the Trump Administration’s assault on liberal democracy, something jumped out at me. It was the age of the laws now being used to attack liberal democracy in the US. The question of ‘liberty’ or ‘freedom’ occasionally crops up in our politics. But invariably in a way that the ancient theorists of liberty would have regarded as the essence of decadence. It’s something that’s owed us, not something that makes demands on us that we need to defend - with our fortitude - moral, physical if necessary and intellectual.

The black-outs imposed on London during the Blitz were an expression of British liberty — of the ability of a people to impose constraints on themselves to fight for the existence of their community and to make collective decisions in defence of each of its members. The lockdowns during COVID were precisely the same kind of constraint whether or not you think they used that liberty wisely.

If we cared about liberty we’d systematically go about cleaning up our statute books with a specific eye to things that could be exploited as on-ramps to authoritarianism. So the Democrats in the US for instance would have put on their agenda reforming the pardoning power. Instead they took advantage of it to favour Joe Biden’s family for Christ’s sake! They should have tried to clean up some of the statutes that are being used today in the US. But, as they barnstomed the country talking about the dire threat to democracy, what did we hear from them about making America safe again (from tyranny as the founding fathers had hoped)? Nothing.

If we cared about liberty, all those restrictions we accepted in the wake of 9/11 would have been sunsetted and kept under review. But we mostly only hear the sunsetting argument when laws obstruct business freedom, even though anti-red tape policies are similarly ill thought through.

At least I can claim that, in my youthful naivete, I learned the hard way that no-one cares about that stuff. As I explained in my post on Lockdowns and Liberty during the COVID lockdowns in 2021.

This short post grew out of a response to Paul Frijters on another thread. Naturally enough, those who don’t want to lockdown are telling us about our precious liberties. You know those we fought for at Gallipoli, and Iraq and Afghanistan.

In any event, I strongly agree with the anti-lockdown folks that liberties are being trampled on. I’m not sure when we cared about them much, but it’s pretty obvious we don’t now. We’ve been knocking down our civil liberties in government since at least the time Howard understood that he could wedge his opposition by making especially outrageous ambit claims which would then place the Opposition in a dilemma of whether to waive them through (so the electorate won’t be distracted from what it really cares about which is electricity prices) or try to introduce better safeguards to them — in which case pretty obviously they’re soft on terror.

In any event, I think of civil liberties as a two stage business.

I have no problem with democracies imposing restrictions on civil liberties — even draconian ones — providing the circumstances warrant this and they’re subject to strong safeguards. (Particularly in time of war). Of course then the question turns to what sort of safeguards. I’d like to see both parliamentary and sortition based safeguards. So I don’t see lockdowns as inherently interferences with our liberty. They can promote them as marshall law promotes them in certain circumstances. As lockdowns and blackouts do in time of war. And as lockdowns would if the currently circulating plague had a case fatality rate like Ebola or even SARS 1.

That the COVID measures have not been subject to appropriate safeguards seems completely clear to me. The thing is, this is a pretty new question for most people. I’ve actually shown some attention to this question for at least four decades. I say that because I can identify when I first did something about it. I wrote a private members bill for Senator John Button in 1981 when he was in opposition to introduce due process and the coming before a judge wherever parliamentary privilege was used to penalise someone (or perhaps just to jail them).

It has always amazed me that while we go on about our precious liberties, our constitution (I mean the fabric of our constitution not just the document) has precious little in the way of safeguards and no-one shows much interest in them. I’m not really talking about bills of rights, which come with their own ideological baggage. I’m talking of simply thinking what mechanisms would be the first to be used by authoritarians trying to take away our liberties.

Parliamentary privilege is an obvious example, but so are so many other things — for instance the government’s control over prosecutions. But I’ve not seen much agitation on this score from those now campaigning against lockdowns as compromising our liberties. (I’m not talking about Paul here, so much as the business community, the right wing of the Coalition, and all those most influential in our polity opposing lockdowns and sometimes — as with Paul — mask mandating.)

I recall speaking to an independent member of the Victorian Parliament who was leant on to extend Dan Andrews State of Emergency for many many months. I suggested to them when the pressure came on that they should agree to extend it on a month-by-month basis and not budge from that position. This is precisely the kind of oversight I’m talking about, though I’d like to see it considerably strengthened.

I remember at the time Howard was marching our troops off to Iraq “just so we were ready if it came to that” — you know the drill — trying to get the ALP interested in entrenching some legislation or amendment to our constitution supporting a position in which Australian troops could not be deployed in combat overseas without a majority vote in both houses (I’d add a sortition based body if anyone asked these days). Apart from believing it was good policy, I thought that would be a good way to get on the front foot, and place the ALP’s hesitancy about going to war in Iraq in its best possible light.

Anyway, the hard heads knew better, pointing out that one day they’d be in government and it would be terrible if they couldn’t head off to the next hotspot and make sure Australia was there defending all that’s right in the world. Like we were already doing in Afghanistan.

Great fun

Using the rule of law to dismantle liberty

In the early months of 1953, Joseph McCarthy's anti-communist crusade was reaching a crescendo. Artists and intellectuals from Charlie Chaplin to Orson Welles were exiled while Paul Robeson had his passport revoked, Zero Mostel was blacklisted, and J. Robert Oppenheimer had his security clearance revoked. Leonard Bernstein was investigated and Langston Hughes publicly distanced himself from other leftists to avoid jail. Most everyone in the world of arts and education had decisions to make: should they speak up against the attack on constitutional and democratic government or should they fade into the background, hoping that their silence might protect them.

It was at this time that Hannah Arendt began to speak out against the dangers of McCarthyism. Speaking out for Arendt held real personal risk. She and her husband Heinrich Blücher had recently become naturalized citizens of the United States—she in December of 1951, Blücher in early 1952. When Arendt received her U.S. passport she called it that "beautiful book." But she worried about her husband: the Nationalities Act of 1940 had made it possible to denaturalize anyone who had lied on application for citizenship and Blücher had hidden the fact that he had been a member of the Communist Party in the 1920s and 1930s in Germany. Emma Goldman had been denaturalized on similar grounds. Then Congress passed the McCarran-Walter Act in 1952 making it legal to denaturalize and deport U.S. citizens if they were suspected of communist or subversive activities...

Despite her worries, Arendt spoke out both privately and publicly. In a letter to Karl Jaspers from March, 1953, Arendt writes that the McCarthyism movement is corroding American freedoms and not generating active resistance:

"Can you see how far the disintegration has gone and with what breathtaking speed it has occurred and up to now, hardly any resistance? The whole entertainment industry and to a lesser extent, the schools and colleges and universities have been dragged into it. It all functions without any application of force, without any terror. And yet the whole thing eats its way further and deeper into the society. They are introducing police methods into normal social life because without exception, they name names. They make police agents of themselves after the fact. In this way, the enforcement system is being integrated into the society."

Around the same time Arendt also published an essay, The Ex-Communists, in which she argues that the right to dissent is at the core of American democracy. "Dissent belongs to this living matter as much as consent does." Any attempt, she adds, to limit dissent and impose a true version of American opinion would destroy American democracy, not save it. The inclination to punish subversive speech is, she argues, simply the "methods of the police, and only of the police."

Arendt adds to her argument that dissent is central to American democracy in her essay "Civil Disobedience." Amidst the chaos of the 1960s, she writes that we need to develop a political institution that can mobilize citizens and bring about political and social change, and that does so while remaining within the constitutional and legal frame of legitimate action...

Today, it is worth recalling Arendt's foundational defense of public dissent as well as her outspoken resistance to legalized denaturalization based on political opinions. We are living through another moment when American politics is aiming to quell dissent. President Trump has made it clear that anyone who challenges him will be targeted and punished. It is one thing when woke cancel culture punishes those who deviate from the party line criticism and calls for cancellation. But it is fully another thing when the canceling is done by the United States government led by the President...

Beyond the President's patrimonial and personal attacks on those he sees as his enemies, he is mobilizing the government to quell dissent across society. Just this week, President Trump invoked the Alien and Enemies Act of 1798 that gives the president authority to detain and deport citizens of nations who threaten the United States in times of war. The Act has previously been used only during actual wars—the war of 1812, WWI, and during WWII to justify the internment of Japanese nationals. The President claims that the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua is threatening the United States on behalf of the Venezuelan government, which he argues allows him to deport any Venezuelans connected to the gang...

The President also has activated sections 237 and 212 of the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act—the very same provisions that Arendt worried could lead to the destruction of American democracy and the abolition of the foundational American respect for dissenting political opinions. Section 212 of the act applies to green card holders and permanent residents of the United States, granting the U.S. government broad discretionary power to exclude or deport non-citizens based on foreign policy concerns. By ordering the arrest and deportation of Mahmoud Khalil, a Palestinian graduate student at Columbia University known for his pro-Palestinian activism, President Trump showed that he is not only willing, but also determined, to punish and deport political enemies, even when they have committed no crime and have a green card allowing them permanent residence in the United States...

The fifth thought we need to hold in our heads is that the statute giving the President this authority is or should be unconstitutional and is fundamentally at odds with the American tradition of democracy and dissent. Jeffrey Isaac may exaggerate when he writes that we are now living in a police state. But Isaac is right that at the root of President Trump's actions is a fundamentally anti-American crackdown on dissent. We are in a fight for the kind of American constitutional and republican and democratic country we want to have.

The arrest of Khalil Mahmoud is an offense to every citizen of the United States, and it sets a precedent that endangers us all.

What’s with the encrazification?

We lost a lot of people during Covid—and most of them are still alive.

Joe Rogan

Very interesting reflections from Helen Lewis on those people who’ve made transitions like Musk has from normie to troll. I have little doubt that it’s a very important subject. And Gresham’s Law provides the paradigm for what’s going on. Gresham’s Law holds, I am sure you recall, that bad money drives out good. (Copernicus came up with the same idea, but he already gets enough attention.) Once currency that’s clipped or counterfeit is circulating, those who think they may have received such currency will prefer to use it, instead of their ‘good money’ which they will hoard.

Now there are numerous systems in which the life world of the surrounding culture provides a kind of anchor — a barrier of shame beyond which most people will not go. But the incentives push towards the barrier. If you push them you can make more money or win more votes or move up a little faster in your career.

An ‘equilibrium’ sits right at this margin. But over time people take small liberties. It moves slowly. But culture changes underneath it and at some stage, a sufficiently shameless person (I’m looking at psychopaths everywhere and at Donald Trump in particular) just walk past that barrier and right into history.

The shame barrier is the barrier when hypocrisy is still paying the tribute vice pays to virtue. We’re beyond it when a politician like Donald Trump or Elon Musk says something completely untrue, like that Zelenskiy has a 4% approval rating, but feel no compulsion to explain or defend themselves. It’s of no consequence to them and they move on to their next bit of reality sculpting.

Ezra Klein documented some crucial moments of destruction of American political culture in his previous book. A less than notable Congressman heckled President Obama during his State of the Union address “You Lie”. He got something like $2 mil in donations. And so Gresham’s Law wreaks its havoc.

And, as Helen Lewis documents, this is happening to individuals on social media. Many of us feel the pull. Get a bit nastier, get more retweets. And on it goes.

We are just about to hit the fifth anniversary of the first British lockdown, and so I have been thinking about the lingering after-effects of Covid. Not just in the longterm sickness numbers—although those are terrible, and the politics of reducing them are fraught—but the psychological consequences of that prolonged period of isolation. Five years on, it's clear that there were profound effects from driving so many people away from their loved ones, their communities and their workplaces . . . and towards their screens. Covid might have been a respiratory disease, but the pandemic era profoundly affected our brains.

You might not have heard of Neil Oliver, but he's one of those people who has drifted away from a successful mainstream career into the strange realms of conspiracism. He used to present Coast on the BBC, but he's been a vaccine sceptic for a while, and frequently hosts guests with some eyebrow-raising views about "Zionists" and how the elite is run by "Jewish mobs." In response, GB News moved some of his output online to avoid the scrutiny of the television regulator, Ofcom.

I was recently reading an article by a former friend of Oliver's, who can't square his current persona with the man he once knew, and therefore wonders whether he really knew Oliver at all. "He was intelligent, curious, funny, irreverent, and self-deprecating – seemingly the antithesis of the grizzled bloviator who now often pops up, occasionally on my social media feeds, showering the airwaves with his views and wild theories."...

Sam Harris on Elon Musk immediately comes to mind: "The friend I remember did not seem to hunger for public attention," Harris wrote in January. "But his engagement with Twitter/X transformed him—to a degree seldom seen outside of Marvel movies or Greek mythology. If Elon is still the man I knew, I can only conclude that I never really knew him."...

The whole of Doppelganger, Naomi Klein's book on Naomi Wolf, addresses this subject. She suggests "a kind of equation for leftists and liberals crossing over to the authoritarian right that goes something like this: Narcissism (Grandiosity) + Social media addiction + Midlife crisis ÷ Public shaming = Right wing meltdown."

All of those elements are present in the Neil Oliver story: a big ego, real success, a sketchy attention to detail combined with a desire for attention (leading to embellished anecdotes, such as passing off a Woody Allen line as his own). Add to the checklist a sense of grievance—the feeling that snooty elites were looking down on him. (Oliver had success as a pop-archaeologist presenting Coast, but attracted grumbles from established academic historians when he became a "face" of BBC factual programming. In a similar way, the pseudo-archaeologist Graeme Hancock is obsessed with his alleged marginalisation at the hands of Big Trowel, but . . . he's the one with all the bestsellers and a Netflix show, which most academic archaelogists can only dream of having.)...

In midlife, showbiz careers often fade away—as gatekeepers find younger and more fashionable proteges and because audiences want to look at hot people. In their 40s and 50s, people in all fields realise that their career has probably peaked, possibly at somewhat lower an altitude than they thought they would achieve. Or, more basically, they suddenly realise that death isn't just something that happens to other people—old people—but will happen to them, too.

And then add in social media. The Covid years isolated many people from the Brownian motion of regular society, cooping them up with self-selected groups online. And in isolation, groups have a well-known tendency to drift towards the extremes.

The attention economy, meanwhile, offers huge rewards for saying provocative things (financial and in terms of attention) but the cost is a huge backlash, too. That kind of hate is hard enough for anyone to deal with, let alone a fragile narcissist, a vulnerable oddball or anyone with imposter syndrome. For some, social media can be used as a form of self-harm, like drinking or gambling. It's even worse than those things, sometimes, because a troubled person can associate themselves with a social cause, and then shrug off any criticism as attacks on The Movement.

My question is this: how many people has this happened to? I suspect that famous people are more likely to "Go Culture War", because a) they have had previous success, and so their sense of midlife loss is greater; and b) they are better placed to self-harm through social media. But clearly this is not limited to celebrities: most of us know someone who hasn't been quite the same since 2020...

Before the next pandemic, we should think carefully about ways to contain the disease early and efficiently, in the hope that lockdowns won't be needed.

Cher

For a person so given over to her image, she’s extraordinarily unaffected, straightforward and amazingly enough for an American, self-deprecatory. Few people preserve as much normality through the tidal wave of nonsense as she has.

I also love the song.

She said

"Tell me are you a Christian child?"

And I said

"Ma'am I am tonight"

Why I wrote The Crucible: Arthur Miller

I remember thinking what a gutsy guy Miller was when reading his memoirs. This piece is of relevance as America plunges back into the paranoia that characterised it during the McCarthy era.

As I watched "The Crucible" taking shape as a movie over much of the past year, the sheer depth of time that it represents for me kept returning to mind. As those powerful actors blossomed on the screen, and the children and the horses, the crowds and the wagons, I thought again about how I came to cook all this up nearly fifty years ago, in an America almost nobody I know seems to remember clearly. In a way, there is a biting irony in this film's having been made by a Hollywood studio, something unimaginable in the fifties. But there they are—Daniel Day-Lewis (John Proctor) scything his sea-bordered field, Joan Allen (Elizabeth) lying pregnant in the frigid jail, Winona Ryder (Abigail) stealing her minister-uncle's money, majestic Paul Scofield (Judge Danforth) and his righteous empathy with the Devil-possessed children, and all of them looking as inevitable as rain.

I remember those years—they formed "The Crucible" 's skeleton—but I have lost the dead weight of the fear I had then. Fear doesn't travel well; just as it can warp judgment, its absence can diminish memory's truth. What terrifies one generation is likely to bring only a puzzled smile to the next. I remember how in 1964, only twenty years after the war, Harold Clurman, the director of "Incident at Vichy," showed the cast a film of a Hitler speech, hoping to give them a sense of the Nazi period in which my play took place. They watched as Hitler, facing a vast stadium full of adoring people, went up on his toes in ecstasy, hands clasped under his chin, a sublimely self-gratified grin on his face, his body swivelling rather cutely, and they giggled at his overacting. ...

McCarthy's power to stir fears of creeping Communism was not entirely based on illusion, of course; the paranoid, real or pretended, always secretes its pearl around a grain of fact. From being our wartime ally, the Soviet Union rapidly became an expanding empire. In 1949, Mao Zedong took power in China. Western Europe also seemed ready to become Red—especially Italy, where the Communist Party was the largest outside Russia, and was growing. Capitalism, in the opinion of many, myself included, had nothing more to say, its final poisoned bloom having been Italian and German Fascism. ...

"The Crucible" was an act of desperation. Much of my desperation branched out, I suppose, from a typical Depression-era trauma—the blow struck on the mind by the rise of European Fascism and the brutal anti-Semitism it had brought to power. But by 1950, when I began to think of writing about the hunt for Reds in America, I was motivated in some great part by the paralysis that had set in among many liberals who, despite their discomfort with the inquisitors' violations of civil rights, were fearful, and with good reason, of being identified as covert Communists if they should protest too strongly. ...

I had read about the witchcraft trials in college, but it was not until I read a book published in 1867—a two-volume, thousand-page study by Charles W. Upham, who was then the mayor of Salem—that I knew I had to write about the period. Upham had not only written a broad and thorough investigation of what was even then an almost lost chapter of Salem's past but opened up to me the details of personal relationships among many participants in the tragedy.

I visited Salem for the first time on a dismal spring day in 1952; it was a sidetracked town then, with abandoned factories and vacant stores. In the gloomy courthouse there I read the transcripts of the witchcraft trials of 1692, as taken down in a primitive shorthand by ministers who were spelling each other. But there was one entry in Upham in which the thousands of pieces I had come across were jogged into place. It was from a report written by the Reverend Samuel Parris, who was one of the chief instigators of the witch-hunt. "During the examination of Elizabeth Procter, Abigail Williams and Ann Putnam"—the two were "afflicted" teen-age accusers, and Abigail was Parris's niece—"both made offer to strike at said Procter; but when Abigail's hand came near, it opened, whereas it was made up into a fist before, and came down exceeding lightly as it drew near to said Procter, and at length, with open and extended fingers, touched Procter's hood very lightly. Immediately Abigail cried out her fingers, her fingers, her fingers burned." ...

In this remarkably observed gesture of a troubled young girl, I believed, a play became possible. Elizabeth Proctor had been the orphaned Abigail's mistress, and they had lived together in the same small house until Elizabeth fired the girl. By this time, I was sure, John Proctor had bedded Abigail, who had to be dismissed most likely to appease Elizabeth. There was bad blood between the two women now. That Abigail started, in effect, to condemn Elizabeth to death with her touch, then stopped her hand, then went through with it, was quite suddenly the human center of all this turmoil. ...

I was also drawn into writing "The Crucible" by the chance it gave me to use a new language—that of seventeenth-century New England. That plain, craggy English was liberating in a strangely sensuous way, with its swings from an almost legalistic precision to a wonderful metaphoric richness. "The Lord doth terrible things amongst us, by lengthening the chain of the roaring lion in an extraordinary manner, so that the Devil is come down in great wrath," Deodat Lawson, one of the great witch-hunting preachers, said in a sermon. ...

About a year later, a new production, one with younger, less accomplished actors, working in the Martinique Hotel ballroom, played with the fervor that the script and the times required, and "The Crucible" became a hit. The play stumbled into history, and today, I am told, it is one of the most heavily demanded trade-fiction paperbacks in this country; the Bantam and Penguin editions have sold more than six million copies. I don't think there has been a week in the past forty-odd years when it hasn't been on a stage somewhere in the world. ... It is only a slight exaggeration to say that, especially in Latin America, "The Crucible" starts getting produced wherever a political coup appears imminent, or a dictatorial regime has just been overthrown.

Retail recycling is mostly bullshit

As I documented here in the case of plastic bags, so goes most kerbside recycling.

LI;HR (I.e. Looks interesting, haven't read — yet)

John McWhorter drops in

I’ve always been a fan of John McWhorter, though my fandom has been growing recently. As an out and proud anti-woker, I’m supportive of his own calling bullshit on so much wokery. But he’s a man after my own heart as his disagreements with Glenn Lowry illustrate. Glenn isn’t hugely troubled by Trump — what with the empirically proven inverse relationship between omelettes and unbroken eggs. McWhorter is horrified, and always thought of woke as a mistake, but nothing compared with inviting a career criminal psychopath to set up his headquarters in the Oval Office.

Enjoy the podcast above. And the NYT column he penned on his return from Australia. Regarding that, it’s interesting how we're kept at arms length from the idea that a dominant indigenous language is Kriol in Australia. Just like we like our wildernesses pristine, so it is with our indigenes. Our culture is more comfortable with pristine authenticity and noble savages than it is with the wreckage and bric-a-brac from which we need to build something better.

I spent last week in Australia, and had some experiences that made the trip well worth the long flight. I devoured what I am reasonably sure is the best lamb meat pie on earth, I saw an echidna and I had some illuminating conversations about linguistics with professors and students. In one of those conversations, I learned about a language kerfuffle from a few years ago that took me back to the 1990s, and reminded me of how beautiful and complex nonstandard speech can be.

In 2021, Mark McGowan, who was then the premier of Western Australia, made a video informing Aboriginal people about safety precautions during the Covid-19 pandemic. He stood next to an Aboriginal interpreter, who translated his statements into Kriol, the language many Aboriginal people in Australia speak. So, for instance, when McGowan said, "This is an important message to keep Aboriginal people safe," it was followed by the interpreter saying, "Dijan message i proper important-one to keep-im everybody safe-one."

Commentary in and out of Australia was mean, calling it racist and condescending for McGowan to have statements directed at Aboriginal people translated into mere baby talk. Typical was "This isn't a mix of languages, this is just ignorant usage of English. Apparently saying this is 'bad English' is racist, but I guess I'm a racist because this is just bad English."

The dust-up revealed that even in Australia, many people are unaware that Aboriginal people have transformed English into a new language entirely. To many people, the idea that Kriol is a legitimate form of speech is unfamiliar, and even absurd. It reminded me of the American public's reaction to Ebonics — i.e., Black English — in 1996, when the school board in Oakland, Calif.,suggested that Black children would learn to read more easily if Black English were presented alongside standard English as a teaching strategy.

In both cases, people miss that nonstandard speech is not, in any scientific sense, substandard. These forms of speech are not broken. In fact, there is order, subtlety, and even majesty in these ways of talking. ...

In the video, Kriol is used slowly, one sentence at a time, expressing rather elementary concepts, which helped give viewers the mistaken impression that it was just corrupted English. But that's not how it, or any language, is used in everyday communication. Here is a more representative Kriol sentence: "Dijan lilboi gemen im-in gedim long-wan stik en pukum la jad hol." This is hardly baby-talk English, given that it is so hard to even glean what the baby in question would even be saying. It means, "This little boy got a long stick and pushed it down into the hole."

"Dijan" — roughly pronounced "DEE-jun" — is what happens when you say "this one" repeatedly across generations. It is now unrecognizable as derived from "this one" except with study. It is a word of its own just as "daisy" is a different word from what it started as, "day's eye." The "la jad hol" at the end of the sentence is "to that hole." "Jad" is "that" after the same process that made "this one" into "dijan." "La" is "to" for reasons that need not detain us, but obviously no baby says "la" for "to"! The word "gemen" signifies that this sentence is describing something from a dream, based on the old British word "gammon," for "inauthentic."

So, more closely examined, to hear Kriol as broken English is like thinking of lamb as broken beef. Kriol is very much its own thing, a separate language from English, such that Aboriginal people who use both English and Kriol are bilingual (and often trilingual, when they also speak their native Indigenous languages, of which there were once more than 250 in Australia). ...

I sense that three decades on, we have gotten somewhat past this. Black English gets a little more respect than it used to. This is partly because of the teachings of the public-facing linguist, who is more common nowadays than he was then — because social media makes it easier to be one. The mainstreaming of hip-hop has also played a role.

But it's one thing to hear Black English as expressive, dynamic, cultural — i.e., cool. It's another thing to understand that it's complicated, with rules and intricacies, like Arabic, Latin and Thai. Just as with Kriol, because it is based on English and we are taught to worship the standard dialect as the "real" one, Black English can seem unruly, abbreviated. ...

Humans are hard-wired for complex language. Children, if raised on anything less, create a complex language out of what they hear. Linguists and anthropologists have recorded no humans speaking language that fails to fulfill all communicative needs. I hope the folks Down Under will come to understand that Kriol is one of their national treasures just as Black English is one of ours.

I’ve mused on the same point. Not earth shaking, but if it’s got you wondering, have a poke around in it.

Heaviosity half-hour

The captive imagination

I’m less than half-way through this book on addiction but so far I think it’s marvellous. It’s by a psychotherapist with a strong philosophical bent - though by ‘philosophical’ I don’t mean there are lots of references to the philosophical canon. Fortunately there are not. I mean that his thinking is, simultaneously thinking about thinking.

I’ve excerpted a fair bit of Chapter 3 below, but before we get fully underway, here’s one highlight where the author intimates that maybe the academic and the addict have more in common than they think.

Once a story lodges and hardens, it is difficult to tell a different one. We find ourselves repeating the same lines, the lines we know best. ... Few stories are as inexhaustible as those purporting to explain the brain, with their narrative ambitions as labyrinthine as the dense neural connections they attempt to untangle. ...

Billions of taxpayer dollars are earmarked for sustaining this sometimes-helpful fiction, with various actors in the biomedical-industrial complex playing their part in the production: academic institutions, corporations, pharmaceutical companies, career scientists. ...

The brain disease paradigm has shaped, supported, and maintained countless careers, including my own. Scientists and researchers, for their part, are pressured to accommodate this worldview for pragmatic reasons of self-preservation. Researchers remain attached to their paradigm because it can provide explanation, a window into neurobiological issues driving the addict—but also because it pays, it legitimizes them as scientists, it allows them to maintain credibility in academe. Just as individuals might deepen their attachment to a drug because it provides a pleasurable change in consciousness—and because it sustains them, preserves a sense of self, gives meaning to their wanting, and fits into the world as they know it.

And so, on with the rest of Chapter 3.

Darkness Within Darkness

For technicians, nothing is possible.

—André Derain

It is clear right away if a family is unaccustomed to being together. They will sit in my office ill at ease, breath labored, their bodies stiffened as if preparing for bad news. It seems they had been avoiding one another for fear of some difficult truth coming to the surface and making a mess of everything. They brace themselves for the inevitable recognition.

Steve, the eldest son, was referred to me for a severe prescription painkiller addiction; he was snorting about $120 worth of crushed oxycodone pills daily. He was in his early twenties, unemployed, living at home after leaving college. He had failed his classes and floundered depressed and isolated before taking a medical leave extending for three years now. They were a working-class family living in Staten Island, ground zero at the time for New York City's opioid problem. I had called the family together because it was important to hear what everyone had to say and to better understand how life at home might be influencing Steve's problems, for better or worse. I also wanted to observe everyone interacting, get a sense of how they communicated and related with one another.

"We want to help him, but nothing is working," his mother said. "It is awful what happened to him. He was a great student, lots of potential. I know he doesn't want to do this. We've tried everything, detox, therapy. He can't stop himself."

I saw his father bite down hard on his trembling lower lip, struggling to stave off the sobbing. His sister, a petite woman a few years younger, seemed irritated. His mother was also frustrated, a single tear rolling down a stern face. She had come to my office from her job as an administrator in a downtown bank, wearing a sharp business suit. Everyone looked tired and washed out. The toll Steve's addiction was taking was obvious.

It wasn't clear that Steve wanted to stop, contrary to what his mother said. He had come with his family to my office; that was a good sign. But it didn't seem he had a choice in the matter. He had a certain passivity to him, as if he had learned to play along with whatever was asked of him so long as he got what he needed. He was tall and burly, sitting on his hands like a child, motionless and apparently imperturbable. His half-lidded glassy eyes were as inexpressive as wet stones. He seemed to be zoned out daydreaming. He was clearly high.

I felt the anger in the room, the family's helplessness and confusion. Everyone was hurt and frustrated because of Steve's choices. But they also weren't sure whether his addiction allowed Steve to choose anything other than drugs in the first place. Or maybe he was choosing; maybe he was getting exactly what he wanted and to hell with everyone else. Were they all just fooling themselves? Perhaps Steve had turned into every parent's nightmare: "a lying and conniving junkie," as his mother later put it.

Steve had come to a dead end, carrying his family with him. They wanted to shake some reason into him, wake him up to reality. But he was no longer a son, a brother, or even a human being: he had become "a junkie," a pill-fueled automaton impervious to moral or rational guidance. There was nowhere for the anger to go. This may be why they were so uncomfortable when compelled to sit with the situation: they resembled a hissing cauldron ready to explode.

I asked how things have been at home.

"I hide all my jewelry, my cards, we can't keep money around anymore," his mother said. "We don't know who is coming into the house when we are gone. I can't trust a thing he says. I open the door at the end of the day, and I'm holding my breath because he could be dead. A few friends of his have already OD'd due to some fake pills that were spreading around.

"It's too much for us. His sister cannot have a normal life. Everything is about him and his problem. We give him an allowance so that he wouldn't do anything crazy. Just enough to buy his poison. Last thing we want is for him to move on to heroin, like some of his buddies. We tried kicking him out before, but I couldn't sleep at night thinking about the world out there. We've tried making conditions. Nothing sticks.

"Maybe tough love is what we need. Maybe the only reasonable thing is to throw him out and lock the doors and windows. People are encouraging this all the time. But what good is it putting him on the streets if he continues using? He is stuck in this wherever he goes. At least with us he is less likely to get hurt. We're here because we have nowhere else to go. And he just sits there. We can barely get him to talk."

I had been observing Steve as she spoke. He remained in the same position, seemingly not registering anything she said, wearing a blank and distant expression.

"I don't recognize my son anymore," his father said. "I think about what I could have done wrong. We're just an average family, Doc. Problems like anyone else. There was no abuse, no psychiatric problems. Everything they wanted we gave them. Why would he turn to this stuff? What did we do to him?"

A young man anesthetizes his anguish and languishes within an opiated passivity, leaving mountains of pain in his wake. His father shoulders the burden of responsibility. A mother demoralized and depleted, inches away from severing the cord; a sister devastated by the sadness of seeing everything fall apart. The patient, to complicate matters, is not properly a patient at all. Steve seemed the least interested of everyone in receiving help. He was quiet, while everyone else was doing the talking.

Addiction is a problem of systems as much as of individuals. There is a structure that sustains the suffering. A gridlock places everyone into the same helplessness and captivity the addicted person is presumed to feel. The family seemed relieved when I told them that they may not have done anything wrong. Neither Steve nor anyone else, I reassured them, can be held responsible for the current impasse. The issue is that Steve has a disease of sorts.

This brain model can be a good entry point for some patients. It must be wielded strategically. It provided the wedge here that broke the system. "Disease" carries more possibility than does "junkie," a dehumanizing indictment offering little room for change. The model would also be useful at facilitating an important first step and moving his apparent passivity in a healthier direction: a "patient" acquiescing to a medically supervised detoxification to address his physiological dependence, while transitioning to sustained treatment of some kind in the aftermath. It took some work to motivate him, but he knew what was coming. There were ultimately few options given the situation. He was admitted to the hospital within a week of that meeting; he transitioned successfully, with only a few minor complications, to an injection of extended-release naltrexone, the same treatment that Ahmed had attempted and failed.

Steve had detoxed and transitioned to buprenorphine before, though he had relapsed in short order. He may fail again. I provided him information about the "course of disease," spoke with him about "opioid receptor normalization" and the importance of staying the path as his "brain chemistry found a new homeostasis." He remained "diseased" as he experienced persistent withdrawal after transitioning to the injection: "post-acute withdrawal symptoms," such as insomnia and anxiety, can last weeks to months. He was given medicines to "manage symptoms." I worked with his family to incentivize Steve sticking to treatment. Steve continued to inhabit the "sick" role in those early weeks and was guided toward maintaining the commitments that came with that identity.

This role of "brain disease patient" may be helpful for introducing some possibility to the situation and shepherding Steve toward maintenance treatment. But we cannot expect it to carry him through the more important challenges ahead: dispelling his passivity, making healthy decisions (including staying in treatment), navigating situations with an eye toward well-being. This was the difficult truth that his family could not easily assimilate. It could be felt in the anger, confusion, and powerlessness during the family meeting. There was no avoiding it: the onus was ultimately on Steve, despite his being the least interested in taking it on. Something needed to be done that only he could do. No biological vulnerability can explain that truth away.

Addiction is a disease, and it is not a disease. I would talk with Steve about his "abnormal neurochemistry" and "altered reward systems" and at the same time would refer to "his responsibility" and "his freedom to choose." We would explore his values and motivations, initially with great subtlety and care to not leave him feeling manipulated and steered toward making certain decisions. This would lead, later, toward conversations centered more explicitly on commitment making in the service of a fuller life.

The tension between addiction as disease and as a choice had been evident from the first conversation. It was felt in the room, in his family's anger that Steve was abdicating responsibility, in the uncertainty about whether, as an addict or junkie, Steve could be reasonably expected to be responsible at all. The possibilities before us were his to embrace—not his family's, nor mine. Another life is possible. It is up to Steve, ultimately, to work toward it.

This started with encouraging Steve to accept medical treatment, as a patient. It would evolve into more explicitly guiding him toward accepting responsibility, as a human being, for what might become of his life, beyond what anyone else, neither his family nor I, could do for him. Steve would ultimately need to move beyond "patient" and "addict" just as he had moved beyond "junkie," toward new possibilities, beyond what anyone can map out in advance, beyond even the mechanisms of his own brain.

The brain model is only partly about the brain. It is also indebted to behaviorism, and to a lesser extent cognitive science, for its account of human behavior. In all these frameworks, the enigma of consciousness is deemed meaningless, with subjectivity unsuitable to empirical exploration. What is important to addiction is what can be observed by scientists acting intersubjectively: behavior, brain activity, and quantifiable cognitive processes. This is not an entirely empirical stance. As we will see, there are also moral, philosophical, and even religious frameworks that play a role.

This model faces the same problem that any other does: the problem is with us. We have lost the lightness and agility that allows us to enter its abstractions without losing our footing. Wielding any model fruitfully means learning to see through its words and playing with them, as when helping Steve: one of many stories to tell, each with its proper time and place. It also means being vigilant against absolutism or scientism. Otherwise, we risk hardening our theories, and ourselves. Emerson called such calcifications an excrescence of words.

Behaviorism was first postulated by John Watson and B. F. Skinner in the early twentieth century, and has come to be the dominant model for understanding repetitive drug use. It hypothesizes that our behavior is primarily shaped by reward, punishment, and reinforcement. We seek and respond to something compelling, such as food or sex, and we want more of this reward. Similarly, we work to avoid unpleasant and aversive experiences: punishment. Through learning and conditioning, we learn to secure rewards, and to avoid punishments, while giving proper attention to risks and dangers. Our behavior is thereby reinforced—either "positively" by pursuing something compelling, or "negatively" by pursuing whatever gives us reprieve from our distress or punishments.

We learn, for example, to be kind and generous to a prospective sexual partner, even if we might be jealous or anxious, because such behavior is more likely to lead to a fulfillment of our desire. We might also learn to choose a sexual partner complementary to our other needs and desires, and who offers a respite from loneliness—with the intimacy enriching and nourishing as opposed to destructive. But we might also choose a highly destructive and abusive partner, if that is the sort of relationship we have found reinforcing.

Reward seeking is pragmatic, situational, and amoral: the pursuit of the reward or reprieve is balanced against the risks, costs, and punishments that might affect the person. The field of possibility is wide open, encompassing all sides of our nature. We learn to enjoy intimacy with a partner, maintain a career, or play a game in the same way that we learn to be cruel to animals, engage in identity theft, or pursue serial abusive relationships, if these are meaningful to us and we can manage the aversive consequences. This is also how we learn to be addicted: through reward and punishment, conditioning and habituation.

Addiction is therefore considered a reinforced pattern that emerges from the same learning processes that entrench us in other behaviors. The end result of addiction, however, is clearly more problematic than are typical cases of "reward seeking." The most salient difference, according to this model, is that the reward seeking persists in the face of pain and punishment directly attributable to it, with the drug reward (or reprieve) given outsized importance.

Ahmed and Steve had continued using, despite the loss of so many things, despite even the risk of death. It can be frustrating and tragic to witness. And we risk growing as demoralized as the addicts seem to be when all our efforts apparently go nowhere. We want to understand why they are being held captive and how we might intervene to disrupt a process the person apparently cannot.

The power of drugs to create addiction has been attributed, as mentioned previously, to their direct biological activity on the brain—and especially on the so-called reward center, the nucleus accumbens. By virtue of acute neural activation and dopamine effects, the drug produces a powerful, unmediated burst of reinforcing neurotransmission, which is hypothesized to confer on the drug a disproportionate value that drowns out most other considerations. We become conditioned, with repeated use, to pursue the drug to the exclusion of other rewards/reprieves and despite the emergence of painful consequences. The brain becomes programmed, so to speak, to pursue the drug at the cost of everything else. This is why Steve and Ahmed had seemed so helpless. Their own brain was apparently working against them.

Cognitive science dissects this self-destructive programming at the level of mental activity. It clarifies the disruptions in information processing associated with addiction, such as changes in attention, value attribution, and memory. Though important for the brain model as a distinct discipline, cognitive science is fundamentally an extension of behaviorist determinism into the realm of cognition, with its theoretical framework rooted in a behaviorist conceptualization of addiction: compulsive drug seeking as a conditioned process that follows in a predictable manner from certain determinants. For example, cognitive scientists have argued that there are conditioned and unconscious attentional biases toward cocaine-related stimuli that complicate a cocaine-addicted person's ability to steer clear, and that directly guide his decision making. The sight of white sugar scattered across a table, for example, may not register to an addicted person as merely sugar—it may trigger him to consider finding a few lines of cocaine.

Consciousness and subjective experience remain untouched in cognitive science, as with any positivist paradigm. The focus is on understanding the ways that the mind collects stimuli, as well as reconfigures, encodes, and processes them. The brain-mind becomes a kind of computer that has been programmed to respond to sensory data, interpret them, store them away, or act on them in a manner that is as orderly and ineluctable as that of any operating system. What matters, in cognitivism as in behaviorism, is what can be observed.

In addiction neuroscience, these different determinisms—behaviorism, cognitive science, and neurobiology—are stitched together. The overall aim is to identify how drug-related conditioning might become "hardwired" in neural circuits so that addicted individuals lose the "choice" to control their use. Dr. Volkow has therefore called addiction a "disease of free will."

This gives a glimpse into the most foundational imaginaries supporting the brain model. Free will implies decision making transcending the influence of prior causes. It is not an empirical term; it traffics in philosophical and even metaphysical notions, beyond experimental testing. That a neuroscientist would invoke the term is therefore disorienting, comparable to speaking about a fictional character as if he were alive. Equally disorienting is situating free choice within the brain disease model, as if the two are reconcilable. What room is there for freedom in behaviorist-physicalist determinism?

It is a disorientation worth heeding. One reading of Dr. Volkow's statement is that it delineates new possibilities for addiction beyond the determinism of neuro-materialism—and restores to the person the (temporarily compromised) capacity for free choice. I had intended something similar with Steve, guiding him from "junkie" toward "patient" while also gesturing at a freedom beyond all restrictive identifications.

Yet if we are not careful, even "freedom" and "will" might lose their moorings in freedom and be conceptualized in a way that deepens the hold of our restrictive models. Calling addiction a disease of free will might not work to emancipate the addicted, in other words, but, instead, to further diminish freedom more generally, situating it within something like a two-dimensional technical drawing.

[AI synopsis: Section 3 critiques behaviorism in addiction science, examining how neural correlates are often overinterpreted to support the brain disease model. It questions whether cognitive control is truly impaired in addiction, citing research showing addicted individuals can make rational decisions when properly incentivized, and notes how the brain disease model incorporates moral and philosophical assumptions despite claiming scientific objectivity.]

It is important to limit our empiricism with human beings to only what can be observed, be it behavior, cognition, environment-subject interaction, or neural activity. The problem is when we regard these data as our only path toward understanding. From a succinct critique in the Dictionary of Untranslatables:

Behaviorism is thus right insofar as it takes into consideration the limitation of our discourse on the mental. But it is wrong insofar as it seeks to take behavior as the criterion and foundation for knowledge of human nature.

We practice good science when we restrict our data to what is rooted in direct observation. But it is a profound error to restrict a person in the same way. This effectively excludes from consideration our interiority, relationality, and subjectivity, which constitute an integral dimension of our experience as human beings. This error becomes clearer as we examine the fictions informing the idea of "cognitive control," and the restricted notions of human freedom involved.

Properly understood, behaviorism construes cognitive control as a means, not an end. It can be put in the service of nearly anything, including both rational and irrational, "good" and "evil" pursuits. It is what Whitehead called "the reason of Ulysses or the fox": the practical reason aimed at accomplishing some objective, through whatever means it takes. Sinners and saints are equally capable of it. Far from indicating "wise," "free," or "reasonable" decision making, cognitive control is the set of complex higher-order functions by which our goal-directed behaviors are executed, whether we are in thrall to a drug or an ambitious career.

Ahmed was clearly stuck. He was paralyzed by his fraught desire for the drug, his difficulty with overcoming this desire, and the complicated and conflicted worldview that propels his habit: heroin as sanctuary, as sickness, as a solution to sickness. Is his use an impairment in cognitive control or choice? He was clearly unable to stop on his own. It is compelling to conclude he had lost the capacity to pursue more purposeful and difficult objectives, such as abstinence.

Any analysis of his predicament, however, is incomplete without considering his tangle of values, self-identity, and purpose. Overcoming his desire to use might be subordinated to his powerful interest in heroin or undercut by his resignation to a hopeless captivity. Purposeful activity, in fact, may mean something wholly different to Ahmed than controlling his cravings or impulses and maintaining abstinence: it more likely means pursuing his fractured fictions as far as they can take him, despite any hurdles, ambivalence, and problematic consequences. Cognitive control might mean wrangling with himself for one more round, so long as he steers clear of hitting rock bottom.

The party line is that drugs cause addiction by damaging neural circuits and undermining cognitive control. One can make an argument, however, that takes the exact opposite tack, with addictive behavior exemplifying cognitive control. Addiction, after all, puts the implacable machinery of our rationality and decision making into the strict service of a goal, as would happen in the exercise of cognitive control with anything else meaningful to us. But the control is so pervasive in addiction that everything is subordinated to its unrelenting purpose, including our being.

It is also important to remember that a great majority of people who use drugs do so mostly in a healthy manner and at little cost to other activities in their lives. It is difficult to understand how the same drug-related learning processes that are presumed to impair cognitive control might also lead, in the majority of cases, to responsible and controlled use. Either drug use leads inherently to problematic conditioning, heightened drug-related reward, and impaired cognitive control, or it does not. In most cases, drug use clearly ends up being fine, with most people who use drugs enjoying themselves and not going off the rails. The brain model has been amended to fit these data by invoking a genetic vulnerability (what is called a diathesis); the fraction of drug users who develop addiction do so because their genes have put their brains at heightened susceptibility to developing drug-related neuroadaptations. But this drug/diathesis model of addiction, while accommodating certain facts, doesn't address the more fundamental question. Is cognitive control compromised in the first place?

Behavioral economics is the field of study concerned with human choice, and many of its findings challenge the core presumption that cognitive control and rational decision-making are impaired in addiction. A consistent finding from drug self-administration studies, which involve studying drug use in laboratory settings, is that the decision to use substances in addicted people is influenced by the presence of competing rewards, with people adjusting their choices in a reasonable, predictable manner. If it pays well enough to not use their drug, addicted people will abstain, despite how heavily they might value the drug. The right pay will vary for different individuals and different drugs, of course, but researchers have shown that addicted people in laboratory settings will stop administering drugs to themselves in a reliable manner if they are rewarded adequately enough with "alternative or secondary reinforcers" such as money. Some studies have also calculated the exact cost threshold when drug self-administration stops for specific substances, like cocaine. This finding has been duplicated in clinical settings with contingency management strategies, where abstinence is similarly rewarded. These data indicate that rationality remains functional in addiction despite the increased salience conferred on drugs. A calculation is occurring that weighs the drug reward against other things, as expected in people with cognitive control intact.

The same might be said for Ahmed. If we rewarded him adequately for staying abstinent, and if it were clear to him that staying abstinent was not simply an abstract exercise in "self-care," then he might have been more likely to kick his habit. Importantly, one of the challenges that Ahmed faced was an "unenriched environment": he lacked options and opportunities for being naturally incentivized to stay abstinent, such as a rewarding job, relationship, community, and other resources. This was partly a result of the ravages of addiction, with heroin having taken a central place in his life and other paths toward fulfillment subverted. It also reflects social and institutional iniquities that have been observed to contribute to addiction. The presence of an enriched environment may not have been enough to help him—there are plenty of addicts who are deeply enslaved even while sitting in the lap of luxury and with endless optionality—but it is an important aspect of his case to consider.

An intriguing finding in population studies is that people will disrupt a long-standing addiction on their own, and even all at once, without any clinical support. Perhaps they undergo a harrowing experience, undergo a conversion, make a firm commitment, or simply decide that enough is enough. Does cognitive control reemerge overnight? Of course not. The more plausible explanation is that it was never subverted in the first place, as the work of behavioral economists indicates. What likely changed were the purpose, values, worldview, or circumstances motivating the person's choices. These became more aligned with what we might call a more authentic way, with the person pursuing more fruitful (un)realities and decisions.

There is a deeper problem, beyond overemphasizing drug effects on the brain, neglecting the rationality of the addict, or diminishing the importance of nonbiological factors. We have drawn a firm line distinguishing reward seeking related to addiction from pursuits viewed as "normal," such as maintaining a career. A person working a 9 to 5, for instance, and refusing to miss a single day despite illness, a sense of dissociation, problematic ethics, and terrible coworkers, is entangled with a certain reality and value system to the detriment of his well-being. But because his is the common (un)reality, it passes unnoticed. That we are more inclined to see the addict or drug user as mentally impaired and captive to his reward seeking, and this compulsive worker as high-functioning, even admirable, has more to do with our epistemic and moral inertia than with our data. And this inertia is even more foundational than are the values pertaining to drug use specifically.

Free will is one of many moral fictions that have been conflated with the construct of cognitive control. Here are some others: self-control, willpower, impulse regulation, rationality. Cognitive control is, on the one hand, an empirical concept, with some precision and explanatory power in addiction neuroscience; on the other, it is a mongrel concept of various unexamined devotions, all reflecting our dominant moral values—which place a premium on "reason" and "control."

The brain disease model of addiction, in other words, is an ethical parable as much as a conceptual system, offering a moral gold standard for human comportment, with neurobiology and behaviorism serving as the backdrop. Our most exalted value is "Reason": a good in itself, the high-water mark of our moral fiber. We go wrong when we fail to bring ourselves in line with it.

We also go wrong, of course, when we are exercising it. It takes only a moment's reflection to recognize how misguided this idealization of reason is—especially in light of the atrocities humans have perpetrated on one another, with good reason, for all of recorded history. The science of torture, of strategically unjust governance, and of building more effective killing machines should be indication enough that rationality can lend a hand to the most deranged sides of our nature. Rationality is only as good as the ends it aims to achieve, whether it be managing disease, bombing enemies, or sustaining a paranoid delusion. Whitehead's distinction between this promiscuous reason of the fox and the noble reason of Plato or the philosopher (speculative reason) reminds us that rationality need not be aligned with higher values, purposes, or means. But even this distinction remains captive to the prejudice that rationality, though of the higher sort, must be involved in guiding our most authentic way. In combining the "lower" reason of behaviorism with the "higher" reason of antiquated philosophy, the idea of cognitive control reveals its indebtedness to rationalism, from which it inherited a fixation on "reason," in one form or another, as foundational to a good life.

The Middle Ages contribute their own prejudices. Much of addiction neuroscience mirrors the Abrahamic tenet that we fall into temptations on the one hand, through a lapse in faith or in self-control, and rise above our sinful tendencies on the other. There are echoes of Puritanical self-reliance more generally in the brain disease parable: a distrust of "unproductive" pleasure and a view that right action is grounded in impulse regulation and self-control.

The structure and activity of the brain are so ambiguous as to be a kind of Rorschach test: we see what we know, organizing the amorphous spongey mass so that it makes sense to us. What we find is a tale as old as time: a conflict between good and evil, between order and disorder. The midbrain is the "base" aspect of ourselves, the serpents of temptation hissing within our bellies, groins, and limbic systems. The forebrain is our higher self, the steady hand of reason steering the chariot of our beings. Goodness comes from the conquest of our higher nature over the lower. God vanquishing Satan. Order subduing chaos. The evolved prefrontal brain modulating the mesolimbic reptilian proto-brain. Rational civilization reigning over the dark and primitive hordes. Cognitive control directing the impulses. One can go on and on.

These fictions of self-conquest have deep roots in Western morality. It begins with Plato's charioteer, harnessing and steering the wild horses of the self. Then there is the struggle against yetzer hara (evil inclinations) in Judaism, the Jihad al-Nafs (the resistance against our lower tendencies) in Islam, the daily battle with sinfulness in Christianity. Trafficking in these ancient tropes is also the modern contract to control our selfishness within a secular civic-minded morality.

We turn to the brain model with the intention of bringing an objective and morally neutral perspective—a pure empiricism—to a certain expression of suffering. Yet we end up going beyond empiricism to find ourselves repeating common tropes in self-conquest morality: lapses in good judgment are interpreted, without much examination or analysis, as a failure to subdue with Reason the beast snarling within the dark depths of our cerebrum. Perhaps a better way to name our brain-based addiction science is prefrontal morality.

We shouldn't, however, blame the addict, we are told. Their brain isn't working right. A disease, according to Dr. Volkow, of free will. Addicts are deemed so damaged that they are not only incapable of making good decisions but also incapable of making bad ones. The mesolimbic brain decides for them, a destructive default-mode hijacking their lives.

Addiction, as it is currently understood, is a chimera of neuro-scientism and secular self-help gospel: a learned behavior that, due to drug-induced brain hacking, is automatic, irrational, and ultimately anguished. A contradictory and confused behaviorism, tortured into accommodating antagonisms and myths consistent with Western ignorance, including Manicheanism, positivism, even colonialism. These are the dark undercurrents behind the label of "substance use disorder": a fiction spun by the medical establishment, meaningful, comprehensible, and yet deeply inadequate, offering little insight into the human being.

Missing is an understanding of psychoactive substance use as enriching, responsible, and therapeutic. Missing is an adequate accounting of the many unique contexts and larger systems in which our choices occur. Missing is an understanding of why addicted people stop abruptly on their own, after years of supposed neural adaptations, hardwiring, and reinforcement. Missing, as well, is subjectivity and our enduring capacity for freedom and meaning, even during addiction. Missing, most of all, is the human being who narrates, loves, chooses, and suffers.

We have, instead, brain parasites and the zombies who lack immunity to them, anorexic rats hitting the cocaine button, and other images from drug war agitprop. Behavior as mechanical and lifeless as an MRI shot of the skull: the mind replaced with a machine, a broken model, headed for collapse.

[AI synopsis: Section 5 examines how the brain disease model has become institutionally entrenched, with funding structures, academic careers, and research priorities built around it. It discusses both the model's humanistic intentions in reducing stigma and its limitations in potentially dehumanizing addicted individuals by questioning their autonomy and ability to make choices, while also neglecting social and structural contributors to addiction.]

[Section 6 removed]

I offer this critique as a scientist. The work of science is to interrogate our notions: to hang not nature but our own minds on the rack, with even our most familiar and established constructs subjected to scrutiny. And we always return to the thread, in remembrance of what addiction is: a person yearning for understanding, relationship, freedom.

The science of addiction must be aligned with this truth. Not the science of interminable storytelling, one fiction feeding others. Nor the insipid science of careerism or incremental elaboration. It must be robust and nimble, a joyful science endeavoring to move us toward greater realization of our possibilities. In other words: a human science, honest with its origins, embracing both our ignorant foundations and God-like creative imaginations—a science anchored in a total affirmation of being, harnessing knowledge to foster our most fruitful incarnations, our most authentic ways. Knowledge in the service of being, all being, our own and that of others.

In the case of the brain disease paradigm, its endless capacity for elaboration might make for long careers—but what about individual and collective flourishing? Our science is nearly identical to the feverish explorations and experiments that Hans Castorp pursued to fill his days while convalescing from tuberculosis in the sanitarium of The Magic Mountain: hyper-refined and insular, endless, ultimately inconsequential—a sick excrescence of theory. Hans entered the sanitarium a guest but stayed on for several years as a difficult-to-treat invalid.

Meanwhile, as in the war-torn landscape of The Magic Mountain, there is blood on the streets. Though governments continue to spend billions on drug research, the US is in the grip of one of the worst drug-related crises in modern history, with overdoses increasing in incidence; treatments for addiction remaining underutilized and barely effective; harm-reduction strategies, such as free drug testing, not being widely implemented; mass incarceration deepening. Yet the war on drugs rages on. And this is only one aspect of our (un)reality. One doesn't need to look far to find other fictions inflicting violence. The suffering deepens the louder the lies grow.

This is our crisis. It is deeper than the entrenchment of the brain disease model or the ways in which federal funding is allocated; it is even deeper than the failed war on drugs. The crisis is what we have become: the sick conclusions we have reached about ourselves and the world. It is not only the addicted who must reckon with their fictions; there are shades of the nightmare in all of us, including the scientists who presume themselves wide awake in their "objectivity."

Awakening from (un)reality has a common beginning. Seeing the lie, Emerson said, is to deal it a mortal blow. And it is a lie because it obscures our intimacy with what is most immediate, concealing our experience—our possibilities and agonies—under its veils. This is why suffering is so primary and crucial: it provides a clear signal that something is not right. We might startle from dreams into a consciousness of morning.

Thus the "rock bottom" narrative of recovery: it is no longer possible to hide our experience or hide from it. Our suffering must be confronted, as well as all that feeds it. The dream grows tattered, and we might glimpse through its torn skin the obsidian and sunless darkness underneath.

We are not alone in this. The suffering of others offers its own revelations and opportunities. Clinicians engage with such illuminating anguish on a regular basis. Care with words is a necessary starting point. One reason for this was already mentioned: every explanation in clinical work is weighed according to its value in promoting well-being, one person at a time. No word is final. There is another deeper reason for thoughtful discourse, beyond clinical pragmatism. Faced with often impenetrable suffering, the clinician endeavors to engage sensitively with its meanings, working to recognize its inmost and private significance to the person. The inwardness of it compels her careful silence, and she is mindful about obscuring its truth with her own words. She learns to listen deeply.

We also learn in the space of this intimate communion to speak deeply. Forged in such a fire, language finds a clearer form: translucent as glass—and as fragile. We approach our thoughts as windows, not foundations: looking through them instead of attempting to stand on their delicate surface. And we choose our constructs with discernment, recognizing that some might be more useful than others. This receptive and alert stance might extend to everything: a persistent attentiveness, listening with one's entire being, and exercising care with whatever we introduce into the space between us.

I notice this quality in many of my colleagues. I notice it in friends who aren't medical workers as well: a watchfulness with everything that is said and known, care with the bounds of our knowledge. This is the "morality" inherent to the work of knowledge: valuing persistent self-examination and humility, while also recognizing the importance of fearless, even scandalous transgression, breaking through whatever artifice might be threatening domination.

The temptation is to fall into dogmatic certainty, protecting our (un)realities from the slightest threat. This may involve, for those of us identifying as experts and authorities, setting up camp in higher places, while sparing ourselves the booming, buzzing confusion of the world beyond our walls. We spare ourselves the possibility of fuller engagement, too—alienated both from others and from ourselves. We might create an esteemed office in these citadels, but at a tremendous cost. Our lives become brittle as old paper, with echoes of the mausoleum.

Other possibilities exist for how we might understand. There is a kind of knowing that transcends theory or expertise. Anchored in silence, and yet quick with words, we learn to employ our categories more playfully, euphoniously, and even discordantly, without pretending a purchase on absolute truth. Honest clinicians, academics, and scientists meet at this recognition: the incompleteness of all knowledge, our call to constant humility and creativity. The truth of our situation is simple beyond words. So let us abide in it for a moment, on a plane of awestruck disorientation at the edge of the world, pregnant emptiness in all directions.

This is the darkness of consciousness. It is also the darkness of what is before us, with even the blue sky beyond comprehension. The Tao Te Ching might have been referring to precisely this in that obscure passage: darkness within darkness—the gateway to all understanding.

At the heart of our worlds is an immense mystery. Perhaps we might cease speaking altogether and invoke, instead of the word mystery, a boundless ( ). Words can get in the way in general. Gabbing our way into knowledge is bound to deepen our confusion. After all, we might be nowhere, and filling nowhere with what might be nothing. We come to better know our situation, and to know other knowable things, when we remain attentive to the double darkness of ( ).

It can be disorienting to regard being experience as beyond any attribute—incomprehensible in all ways, including whether or not it exists. We grow dizzy floating on the winds of a vast and sonorous silence. We want to brace ourselves, anchor in solid ground, or at least say something about our coordinates so that we are not entirely lost. We are brains, we are holograms, we are quanta, we are spirits, we are the void, we are God, we are souls, we are addicts, we are scientists, we are Americans, we are humans, we are nothing at all. All that I know, we should learn to repeat after Socrates, is that I know nothing.