Civilisation: why its collapsing and how to fix it

And other farcically overblown linkbait I encountered on my travels

Civilisations: they really can collapse you know!

Poncy to the point of just happening to have a cigar in holder when the cameras started rolling, condescending accent to the ready, Kenneth Clark opines about civilisation. As with last week’s write-up of Est, here I am peddling my open-mindedness. Because as much as I’ve learned to turn up my nose at this kind of thing, I was 11 when Civilisation played on our screens — a new phenomenon. The BBC, undisputed leader of world culture was playing a Great Man’s view of life, the universe and everything. And I was being fed into the conveyor belt of life just at the point where it was cool to dismiss the defenders of high culture. And here we are. In any event, I strongly recommend this tweet thread. It takes no time to go through Clark’s three things that can destroy a civilisation.

Fear

Confidence (see ~ “lack of”) and

Exhaustion

since you ask. And each concept is illustrated with some civilisational artefact and then you’re onto the next tweet. How can you resist a story of our own decline — all consumed in a few tweets?

OK: Well, the solutions were a bit of a disappointment, weren’t they — just the second two problems negated? Back to the cigar holder and the poncy accent, I guess :(

Speaking of the collapse of civilisation

HT: a reader. I’ve probably quoted it to you before, but here it is again. After you play the video, read Michael Polanyi writing in 1949:

Though scientists’ income, independence, influence, their “whole standing in the world will depend … on the amount of credit” they could gain in other scientists’ eyes, they “must not aim primarily at this credit, but only at satisfying the standards of science”.

The quickest impression on the scientific world may be made not by publishing the whole truth and nothing but the truth, but rather by serving up an interesting and plausible story composed of parts of the truth with a little straight invention admixed to it. Such a composition, if judiciously guarded by interspersed ambigui ties, will be extremely difficult to controvert, and in a field in which experiments are laborious or intrinsically difficult to reproduce may stand for years unchallenged. A considerable reputation can be built up and a very comfortable university post be gained before this kind ofswindle transpires, if it ever does. If each scientist set to work every morning with the intention of doing the best bit of safe charlatanry which would just help him into a good post, there would soon exist no effective standards by which such deception could be detected. A community of scientists in which each would act only with an eye to please scientific opinion would find no scientific opinion to please. Only if scientists remain loyal to scientific ideals rather than try to achieve success with their fellow scientists can they form a community which will uphold these ideals. The discipline required to regulate the activities of scientists cannot be maintained by mere conformity to the actual demands of scientific opinion, but requires the support of moral conviction, stemming from devotion to science and prepared to operate independently of existing scientific opinion.

Compare Karl Popper:

[Mannheim’s] naïve view that scientific objectivity rests on the mental or psychological attitude of the individual scientist, on his training, care, and scientific detachment, generate as a reaction the skeptical view that scientists can never be objective . . . This doctrine, developed in detail by the so-called sociology of knowledge . . . entirely overlooks the social or institutional character of scientific knowledge . . . if we had to depend on [the scientist’s] detachment, science . . . would be quite impossible. What the “sociology of knowledge” overlooks is just the sociology of knowledge—the social or public character of science. It overlooks the fact that it is the public character of science and of its institutions which imposes a mental discipline upon the individual scientist, and which preserves the objectivity of science and its tradition of critically discussing new ideas.

Did I mention the collapse of civilisation?

Alasdair McIntyre on the Benedict Option

In my impromptu articulation of what I called the Alt-centre, I described it thus:

… how about a fusion of Alasdair MacIntyre, James Burnham and George Orwell together with the idea that outputs from modern academia are mostly useless?

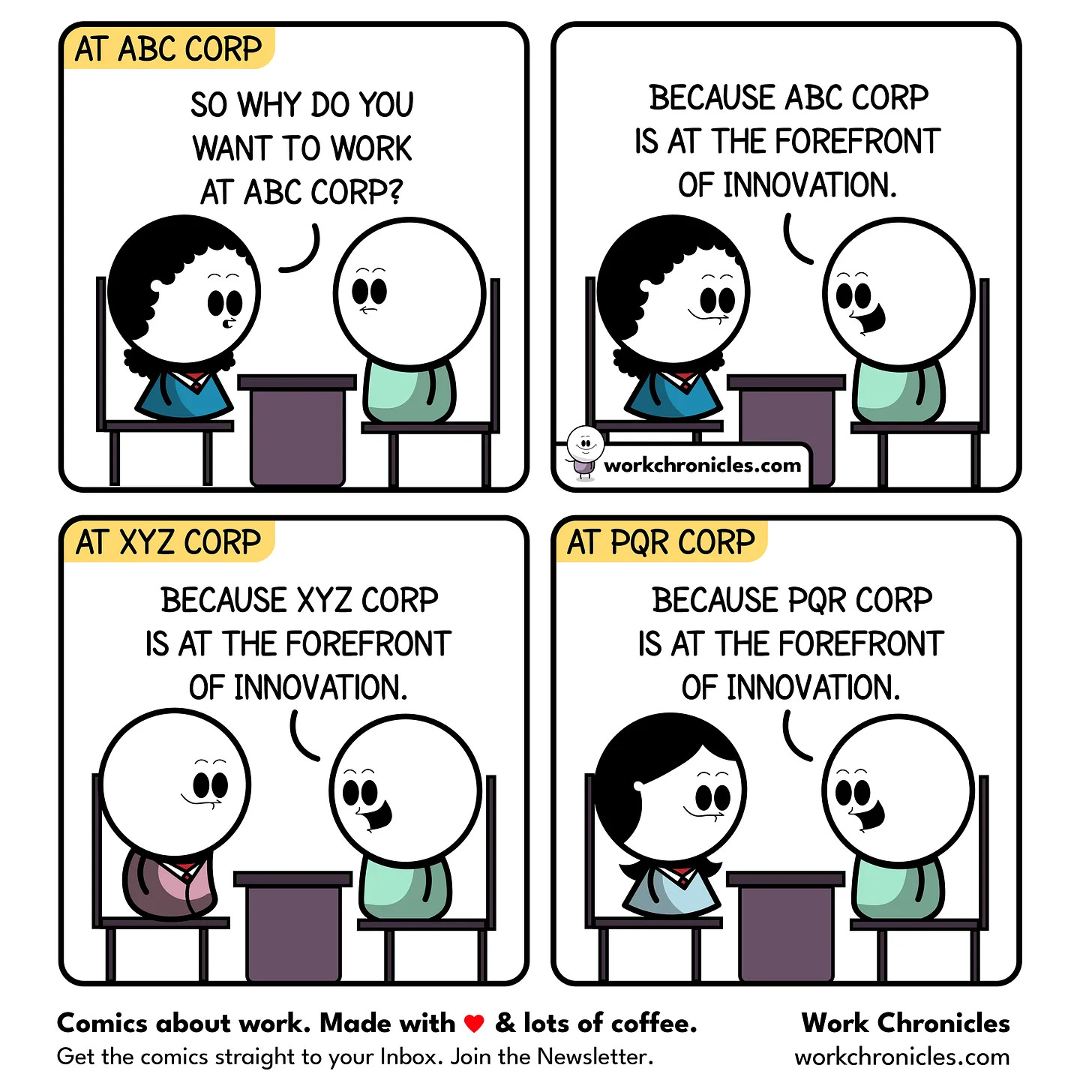

I’d broaden that to a more general sense that mighty institutions that have been built over the centuries since around the Renaissance are somehow collapsing from within. I’d include bureaucracy, electoral politics and the media for a start. There’s also the growing displacement of what critical thought there was (never strongly represented in any society I expect) with thinkiness — a simulation of thinking that is a kind of anti-thinking. This is going on in a strategic retreat near you as we speak. It’s there every time you see those ‘values’ in the foyer as the tacit traditions of institutions gradually atrophy, eaten out by careerism. A part of the appeal of the current crop of right-wing populist politicians is that they do give some voice to people’s sense that something is deeply wrong in our institutions and that it has something to do with them being run by ‘the elites’ for the elites. And then there are all the ideologically tinged versions of thinkiness from DEI, consent, cultural sensitivity and anti-racist training and other wokery along with right wing anti-wokery. If you want to participate in these discussions you just join a side and the arguments fall into place from there. No thinking required.

Anyway I was talking to someone about their start-up today and mentioning some of these things (which the start-up might make some tiny indirect positive impact on). I said we should call Nursia — after the founder of the Benedictine order. That prompted me to look up the last paragraph of Alasdair McIntyre’s great 1981 book, After Virtue to which we owe the concept of “the Benedict Option”. Many people will think all this overblown, and who am I to say they’re wrong. But the words have aged remarkably well:

It is always dangerous to draw too precise parallels between one historical period and another; and among the most misleading of such parallels are those which have been drawn between our own age in Europe and North America and the epoch in which the Roman empire declined into the Dark Ages. Nonetheless certain parallels there are. A crucial turning point in that earlier history occurred when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium. What they set themselves to achieve instead—often not recognizing fully what they were doing—was the construction of new forms of community within which the moral life could be sustained so that both morality and civility might survive the coming ages of barbarism and darkness. If my account of our moral condition is correct, we ought also to conclude that for some time now we too have reached that turning point. What matters at this stage is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us. And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. This time however the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our predicament. We are waiting not for a Godot, but for another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.

Saving civilisation: one citizen assembly at a time

In this podcast in the Transit Zone with Margo Kingston and Peter Clarke, we speak about the recent Tasmanian election. I have the cheek to suggest that the Jacqui Lambie Network had the best platform. (The very same platform that the pundits were so horrified contained no policies). We discuss what contribution citizen assemblies could make to our faltering democracy and finish up by discussing an orange-haired, clear and present danger to democracy. It’s a fun, spirited conversation that Margo wasn’t looking forward to, but was pleasantly surprised that her guest wasn’t the [soft-headed] ‘idealist’ she was expecting. She got a hard-headed (and stroppy) one. But I would say that, wouldn’t I?

You can also listen to it on my Spotify channel or from Substack by clicking below.

Remarkable story: understand it without reading a whole book

Don Watson celebrates the life of Michael Jenkins, creator of ‘Scales of Justice’ and ‘Blue Murder’

And says little about the collapse of civilisation

Don is a very Australian writer, though not self-consciously so. And very funny.

Making a film is less like writing an opera than building an opera house and then writing the opera. And casting it, and building the sets, and so on. And the more elements there are, the more likely that some will be discordant; the more personalities, the more likely that two or more will clash and at least one will be an absolute pain; the more options, the more likely that wrong ones will be chosen. …

Michael Jenkins, who died on March 4, made some of Australia’s greatest TV dramas and never gave a hoot about what art is and what it isn’t, or many of the other questions that students of film like to ponder. He had no apparent theory beyond finding the kernel of a good story, then, by every means the medium allows, uncovering its potential. He was a filmmaking version – and hardly the only one – of the dictum that a writer does not so much make up a story as discover it. Product of an exclusive Sydney school, alternately gentle and sympathetic, wild and profane, he never lost the desire to stick it up whatever passed for authority with as much ingenuity as possible – and violence, where appropriate. …

At a time when Australian film and television was working its way through the nation’s history and the countryside, Scales of Justice was contemporary and urban. … Much of Mike’s best work in one way or another deconstructed male bonding and mateship. They were menacing and sordid as required, yet sympathetic in the curious way that the best screen gangsters are; as if, like Macbeth, they personify the wrong turn that anyone can make. …

Mike, his partner Amanda and their two young children moved to Tasmania in 2006. Around 2016, he began working on a story about a lawyer with incipient dementia trying to defend her client while she still has the cognitive powers to do so. By then, Amanda had seen the first signs of the rare untreatable brain disease – progressive supranuclear palsy – which killed him. We might hope that eight years later he remembered that for every great film there’s at least one that was never made, and that his own great works lifted the whole game and the country a little with it.

Strange object: Erte, Helen of Troy, Screenprint with Foil Stamping

Speaking of science … before the rule was the paradigm

I’ve encountered the indefatigable historian and philosopher of science, Loraine Daston, before. She writes to help explicate to the things that fascinate me like the subterranean changes in the Western psyche associated with the rise of science. Some more passages from the book will be turning up in Heaviosity Half Hour in subsequent newsletters.

Here’s a passage from an essay I wrote on encountering her 2007 book Objectivity a few years ago.

I took a particular interest in this passage from Daston and Galison:

At issue was not only objectivity but also ethics: all-too-human scientists now had to learn, as a matter of duty, to restrain themselves from imposing the projections … of their own unchecked will onto nature. To be resisted were the temptations of aesthetics, the lure of seductive theories, the desire to schematize, beautify, simplify —in short, the very ideals that had guided the creation of true-to-nature images. Wary of human mediation between nature and representation, researchers now turned to mechanically produced images. Where human self-discipline flagged, machines or humans acting as will-less machines would take over. Scientists enlisted self-registering instruments, cameras, wax molds, and a host of other devices in a near-fanatical effort to create images for atlases documenting birds, fossils, snowflakes, bacteria, human bodies, crystals, and flow ers—with the aim of freeing images from human interference. Not only would all schematization be avoided, one turn-of-the-century atlas author assured his readers, but the object of inquiry would also “stand truly before us; no human hand having touched it.”

The ethical duty of scientists requires a particular kind of humility which, as Iris Murdoch asserts, involves “selfless respect for reality”. Yet as she goes on to explain, humility is “one of the most difficult and central of all virtues”. It has a rare and paradoxical quality. As Murdoch assures us, humility is “not a peculiar habit of self-effacement, rather like having an inaudible voice”. In science the practitioner must be selfless, whilst simultaneously intensely active in crafting a vision. (Michael Polanyi is the only philosopher of science I know of whose thinking embarks from this point).

Be that as it may, this mid 19th century ‘objective’ view of science is not ultimately coherent. For the telos or aspiration of ‘objectivity’ is some ‘God’s eye view’ or a ‘view from nowhere’ neither of which humans have access to. This reveals it to be a ‘scientism’ within science as it were – an attempted shortcut to knowledge which ignores crucial difficulties. Sure enough a third stage emerges in Gaston and Galison’s story – “trained judgement”. This is illustrated in modern imaging – for instance medical imaging. This is very often diagnostic. And diagnosis requires someone – a trained ‘expert’ – to identify some point of significance – for instance the point at which the thing being imaged should be regarded as pathological.

Well, as you’ll be able to see from the passage below, she’s at it again. I’m really enjoying Rules. Its problematic is sketched out in this passage.

Rules were many things before they became first and foremost algorithms, i.e., instructions subdivided into steps so small and unambiguous that even a machine could execute them. Some of these earlier genres of rules would still be readily recognizable as such, including laws, rituals, and recipes. But perhaps the most central meaning of rule from antiquity through the Enlightenment is no longer associated with rules at all: the rule as model or paradigm. Indeed, in twentieth-century philosophy, this once-primary sense of rule, listed first in dictionary entries well into the eighteenth century and still invoked by Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), is diametrically opposed to rules.

What kind of model could serve as a rule? The model could be a person who embodies the order rules sustain, such as the abbot of a monastery in the Rule of Saint Benedict (Chapter 2), or a work of art or literature that defines a genre by exemplum, in the way that the Iliad defined the epic in the tradition from the Aeneid to Paradise Lost, or a well-chosen example in grammar or algebra that teaches the salient properties of a much larger class of verbs or word problems. Whatever form the model takes, it must point beyond itself. Mastering the competence embodied by the model goes well beyond being able to copy the model in all its details. Models are to be emulated, not imitated. A writer who reproduced a famous work of literature word-for-word, as in the Borges story in which the protagonist attempts to produce parts of Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote verbatim,6 would not be following but rather repeating the rule-as-model. To follow such a rule involves understanding which aspects of the model are essential and which are merely accidental details. Only the essential features can forge a reliable analogical chain between the rule-as-model and new applications. Reasoning from precedent in common law traditions supplies a familiar example of rules-as-models in analogical action. Not every past case of manslaughter can be plausibly presented as a precedent for the one at hand, and not every detail of even a convincing precedent will match up with the present case. The way seasoned jurists deliberate over legal precedents highlights the difference between a mere example (this or that manslaughter case) and a model or paradigm (a load-bearing precedent with broad implications for many manslaughter cases). The serviceable paradigm must exhibit a high ratio of essential to accidental details and radiate as many analogies as a porcupine does quills.

Speaking of Lorraine Daston: another great podcast

This is a podcast Daston did on the earlier book I wrote about in the previous post above. I thought the book was good when I read it, but listening to the podcast led me to think I’d still underestimated it.

The (US Democrats) Patriotism Problem

As you’ll see, I’ve begun my extract at 5 in a list of 6 points on the Democrats patriotism problem.

5. In Gallup’s latest reading on pride in being an American, 55 percent of Democrats said they were extremely or very proud of being American, compared to 64 percent of independents and 85 percent of Republicans who felt that way. Just 29 percent of Democrats would characterize themselves as “extremely proud,” down 25 points since the beginning of this century.

6. Perhaps most alarming, in a 2022 poll Quinnipiac found that a majority of Democrats (52 percent) said they would leave the country, rather than stay and fight (40 percent), should the United States be invaded as Ukraine was by Russia.

So the patriotism gap is alive, well, and persistent. Why is this? One key factor is that, for a good chunk of the Democrats’ progressive base, being patriotic is just uncool and hard to square with much of their current political outlook. As Brink Lindsey put it in an important essay on “The Loss of Faith”:

The most flamboyantly anti-American rhetoric of 60s radicals is now more or less conventional wisdom among many progressives: America, the land of white supremacy and structural racism and patriarchy, the perpetrator of indigenous displacement and genocide, the world’s biggest polluter, and so on. There are patriotic counter-currents on the center-left—think of Obama’s speech at the 2004 Democratic convention, or Hamilton—but these days both feel awfully dated.

Similarly, liberal commentator Noah Smith observed in an essay simply titled “Try Patriotism”:

I’ve seen a remarkable and pervasive vilification of America become not just widespread but de rigueur among progressives since unrest broke out in the mid-2010s….The general conceit among today’s progressives is that America was founded on racism, that it has never faced up to this fact, and that the most important task for combatting American racism is to force the nation to face up to that “history”….Even if it loses them elections, progressives seem prepared to go down fighting for the idea that America needs to educate its young people about its fundamentally White supremacist character…

Funny that progressives should lose track of this. As David Leonhardt pointed out in the podcast I recently did with him:

[J]ust look at history—the civil rights movement carried American flags while marching for civil rights…think about what an incredible favor it was to them when their counter protesters held up confederate flags, the flag of of treason…the labor unions of the early 20th century brought enormous American flags to their rallies…More recently, the gay rights movement used the military in the 90s as this thing that they said, let us join the military.

That is patriotism….It worked.

That’s right: it worked. And it can work again.

Leonhardt concluded by quoting labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein:

All of America's great reform movements from the crusade against slavery onward have defined themselves as champions of a moral and patriotic nationalism which they counterpoised to the parochial and selfish elites who stood athwart their vision of a virtuous society. So the connection really between patriotism and progressivism is long and proud and progressivism will be much more successful if it is willing to embrace patriotism.

Words of wisdom.

Bureaucracies are NOT risk-averse: a conversation

Me:

Bureaucracies are only risk-averse in particular ways. I call them ‘process hugging’. Think of all the military disasters in history — a large number were engineered by bureaucracies. Was the Pentagon ‘risk averse’ when it recommended the use of nukes in Vietnam and various other places? No — just mentally inflexible.

You could say that the individuals who do best within career bureaucracies tend to minimise risk, but that’s generally risk to themselves, not the interests of those they are there to serve.

Me:

Yes, but considering the matter further, I think focusing on risk aversion is a subtle category mistake. It’s the subtle process whereby the objective of the mission is refracted through the interests of the bureaucracy, which is itself refracted through the interests of the bureaucrat. That’s the essence of the issue. Those interests can be furthered by risk aversion in some instances and by simply ignoring risks in other instances.

Steve Jobs on some similar ideas

Iran is winning the Gaza war

As I tweeted on reading this piece “Documents roughly what I've feared since October 7. Israel seems to have been committing suicide since then in the same way the US launched into unprecedented retaliatory self-harm after 9/11. And it's hard to see how Israel can summon up a new, more hard-headed politics of survival.”

My old economic history teacher said that the economic history of the USA wasn’t interesting because it was so big and rich that its mistakes went unpunished. Well even the USA is regretting its post 9/11 indulgences. But it’s still big, powerful and rich. Israel has a narrower pathway to continued survival.

Amid the continuing destruction in Gaza and the surrounding global fallout, one thing becomes ever clearer. Even as Israel’s war stutters, Iran’s broader campaign against it, and by extension what we might call the American-led order, is growing in strength.

Six months on from October 7, it’s hard to see how Israel can achieve its stated goals of dismantling Hamas and rescuing its remaining hostages. The IDF has only rescued three hostages during its ground operations in Gaza, which is a good indicator of how unrealistic the latter always was. But Hamas is also far from defeated: the terror group’s top three commanders remain at large, and its fighters are already re-emerging in areas of Gaza City that were supposedly cleared. Israel claims to have killed approximately half of its 40,000 fighters, but given the amorphous nature of the terror campaign, and the radicalising effects of Israel’s operations on the Gazan population, the notion of totally eliminating Hamas remains fanciful. …

In the meantime, new threats emerge each day. On Friday, the CIA reportedly warned Israel that Iran is planning to launch an attack with a “rain” of drones, in revenge for its strike on Zahedi. If that happens, Israel will have to respond to an attack on its territory. Iran knows this, and likely calculates that any response, no matter how justified, will be seen as yet another example of belligerence from Jerusalem.

Yet much of this has been lost beneath the noise created by the focal point of the Gaza war. This week, Britain has been in understandable uproar over the death of seven aid workers, three of whom were British nationals. Condemnation piles upon Israel at the UN. Talk of sanctions grows. Washington, once the guarantor of international security, appears unable to stop the violence on both sides. And all the while, Tehran, the Middle East’s most murderous regime, continues to exploit events to its own advantage, and our cost.

Flamingoes celebrate the passion or maybe a horror movie?

Amazing what’s got to happen to get a drink as a flamingo nipper

One of the best Thank God You’re Here episodes.

Heaviosity half hour

Montaigne on the role of advisor

The letters A, B and C refer to text written at different times. From ChatGPT. As you can see, you’re getting his later thinking.

A Version: This represents the original version of the essays as Montaigne first wrote them. These initial versions were the foundation upon which he later expanded.

B Version: After the initial composition of his essays, Montaigne returned to many of them to make additions and revisions. This second layer of text, marked by the letter B, includes further reflections and insights, indicating Montaigne’s evolving thoughts on various subjects. The B additions were incorporated into the essays during the years following the publication of the first edition in 1580.

C Version: The C version refers to the final revisions made by Montaigne towards the end of his life. These were added to the essays for the 1588 edition and any subsequent revisions before his death in 1592. This layer reflects his last thoughts and the culmination of his philosophical development.

[C] The learned do arrange their ideas into species and name them in detail. I, who can see no further than practice informs me, have no such rule, presenting my ideas in no categories and feeling my way – as I am doing here now; [B] I pronounce my sentences in disconnected clauses, as something which cannot be said at once all in one piece. Harmony and consistency are not to be found in ordinary [C] base54 [B] souls such as ours. Wisdom is an edifice solid and entire, each piece of which has its place and bears its hallmark: [C] ‘Sola sapientia in se tota conversa est.’ [Wisdom alone is entirely self-contained.]55

[B] I leave it to the graduates – and I do not know if even they will manage to bring it off in a matter so confused, intricate and fortuitous – to arrange this infinite variety of features into groups, pin down our inconsistencies and impose some order. I find it hard to link our actions one to another, but I also find it hard to give each one of them, separately, its proper designation from some dominant quality; they are so ambiguous, with colours interpenetrating each other in various lights.

[C] What is commented on as rare in the case of Perses, King of Macedonia (that his mind, settling on no particular mode of being, wandered about among every kind of existence, manifesting such vagrant and free-flying manners that neither he nor anyone else knew what kind of man he really was), seems to me to apply to virtually everybody.56 And above all I have seen one man of the same rank as he was to whom that conclusion would, I believe, even more properly apply: never in a middle position, always flying to one extreme or the other for causes impossible to divine; no kind of progress without astonishing side-tracking and back-tracking; none of his aptitudes straightforward, such that the most true-to-life portrait you will be able to sketch of him one day will show that he strove and studied to make himself known as unknowable.57 [B] You need good strong ears to hear yourself frankly judged; and since there are few who can undergo it without being hurt, those who risk undertaking it do us a singular act of love, for it is to love soundly to wound and vex a man in the interests of his improvement. I find it harsh to have to judge anyone in whom the bad qualities exceed the good. [C] Plato requires three attributes in anyone who wishes to examine the soul of another: knowledge, benevolence, daring.58

[B] Once I was asked what I thought I would have been good at if anyone had decided to employ me while I was at the right age:

Dum melior vires sanguis dabat, œmula necdum

Temporibus geminis canebat sparsa senectus.[When I drew strength from better blood and when envious years had yet to sprinkle snow upon my temples.]

‘Nothing,’ I replied; ‘and I am prepared to apologize for not knowing how to do anything which enslaves me to another. But I would have told my master some blunt truths and would, if he wanted me to, have commented on his behaviour – not wholesale by reading the Schoolmen at him (I know nothing about them and have observed no improvement among those who do), but whenever it was opportune by pointing things out as he went along, judging by running my eyes along each incident one at a time, simply and naturally, bringing him to see what the public opinion of him is and counteracting his flatterers.’ (There is not one of us who would not be worse than our kings if he were constantly [C] corrupted by that riff-raff as they are.) [B] How else59 could it be, since even the great king and philosopher Alexander could not protect himself from them?60 I would have had more than enough loyalty, judgement and frankness to do that. It would be an office without a name, otherwise it would lose its efficacity and grace. And it is a role which cannot be held by all men indifferently, for truth itself is not privileged to be used all the time and in all circumstances: noble though its employment is, it has its limits and boundaries. The world being what it is, it often happens that you release truth into. Prince’s ear not merely unprofitably but detrimentally and (even more) unjustly. No one will ever convince me that an upright rebuke may not be offered offensively nor that considerations of matter should not often give way to those of manner.

For such a job I would want a man happy with his fortune –

Quod si esse velit, nihilque malit

[Who would be what he is, desiring nothing extra]61– and born to a modest competence. And that, for two reasons: he would not be afraid to strike deep, lively blows into his master’s mind for fear of losing his way to advancement; he would on the other hand have easy dealings with all sorts of people, being himself of middling rank. [C] And only one man should be appointed; for to scatter the privilege of such frankness and familiarity over many would engender a damaging lack of respect. Indeed what I would require above all from that one man is that he could be trusted to keep quiet.62

A king [B] is not to be believed if he boasts of his steadfastness as he waits to encounter the enemy in the service of his glory if, for his profit and improvement, he cannot tolerate the freedom of a man who loves him to use words which have no other power than to make his ears smart, any remaining effects of them being in his own hands. Now there is no category of man who has greater need of such true and frank counsels than kings do. They sustain a life lived in public and have to remain acceptable to the opinions of a great many on-lookers: yet, since it is customary not to tell them anything which makes them change their ways, they discover that they have, quite unawares, begun to be hated and loathed by their subjects for reasons which they could often have avoided (with no loss to their pleasures moreover) if only they had been warned in time and corrected. As a rule favourites are more concerned for themselves than for their master: and that serves them well, for in truth it is tough and perilous to assay showing the offices of real affection towards your sovereign: the result is that not only a great deal of good-will and frankness are needed but also considerable courage.

Shaun as Giles - fantastic - worth wading through all the other heavy philosophical pieces!

I've a response to Gaston at https://whyweshould.substack.com/p/a-wonderful-straightedge-of-a-book