Greetings

Air Canada liable for its chatbot’s hallucination

Filed under “Cheap LoLs”

I missed this memo from February this year. If you didn’t, apologies. If you did, it’s hilarious. Air Canada’s chatbot made stuff up and Air Canada said why should it be liable. A bit like Goldman Sachs arguing that it shouldn’t be bound by obligations suggested by its advertising — on the grounds that advertising is all so much bullshit and everyone knows.

After months of resisting, Air Canada was forced to give a partial refund to a grieving passenger who was misled by an airline chatbot inaccurately explaining the airline's bereavement travel policy.

On the day Jake Moffatt's grandmother died, Moffat immediately visited Air Canada's website to book a flight from Vancouver to Toronto. Unsure of how Air Canada's bereavement rates worked, Moffatt asked Air Canada's chatbot to explain.

The chatbot provided inaccurate information, encouraging Moffatt to book a flight immediately and then request a refund within 90 days. Moffatt dutifully attempted to follow the chatbot's advice and request a refund but was shocked that the request was rejected.

According to Air Canada, Moffatt never should have trusted the chatbot and the airline should not be liable for the chatbot's misleading information because, Air Canada essentially argued, "the chatbot is a separate legal entity that is responsible for its own actions," a court order said. …

Tribunal member Christopher Rivers, who decided the case in favor of Moffatt, called Air Canada's defense "remarkable."

"Air Canada argues it cannot be held liable for information provided by one of its agents, servants, or representatives—including a chatbot," Rivers wrote. "It does not explain why it believes that is the case" or "why the webpage titled 'Bereavement travel' was inherently more trustworthy than its chatbot."

The unfairness of our super system

I remember when the very first tranche of super was set up under the Accord in (I think) the mid-80s. It seemed far-sighted — it was far-sighted. But almost immediately there was a problem with the NSW Trades and Labour Council led by Barrie Unsworth. In the upshot, we ended up with a flat 15% tax on super. The super funds said nothing else was workable. And they’ve always been people to trust.

It wasn’t my area, but eyeballing it, it seemed awful to me and I said so. A flat tax on a fund that would end up with trillions in it. A Labor Government doing this? Anyway, that was just the start. Super is inherently difficult for political reasons. It’s designed to run for the decades of people’s working lives, yet politicians’ incentives don’t run that far. That’s why I thought it should be kept very simple. Since we were compelling people to save, we shouldn't use tax incentives (which are highly regressive and very ineffective). That meant we could keep the same tax system and just divert some of it into savings. Anyway, what would I know?

In the upshot the system we now have is even worse than a flat tax. It’s a negative tax going disproportionately to the wealty. Chris Richardson takes up the story.

[Beyond the flat tax} there’s an even bigger fairness fail in super, and people don’t know about it. …

Contributions and earnings taxes are both set at a legislated rate of 15 per cent. So, you would expect the after-tax return for every pre-tax dollar of earnings would be 85¢. And you would be wrong. It’s 103.5¢. For every dollar of earnings inside super, taxpayers fork over several cents, meaning the effective earnings tax on super is negative. …

So, how can the total tax take from our superannuation system be only $11 billion this year – the equivalent of just 0.3 per cent of total assets?

It’s because parts of the tax system that make sense in isolation collide in silly ways inside super:

The tax system should encourage saving – and ours does through super.

The tax system should recognise that inflation can artificially inflate capital gains – and ours (indirectly) does through a capital gains tax discount.

And the tax system should avoid taxing the same income twice – as ours does through franking credits.

But super funds get the benefit of all three of these. And super has a very heavy reliance on Australian shares, many of them with fully franked earnings. The upshot is that we’ve massively overdone the concessions. Super funds make earnings on which they have to pay 15 per cent in tax, but then those same earnings often come with a 30 per cent tax credit attached. …

However, while poorer Australians have relatively modest super holdings, richer Australians have huge ones. So, overly large concessions take money from poorer Australians and give it to richer Australians.

The official figures already show that super is an intergenerational blight, and it’s eating away at the budget as it takes from the poor to give to the rich.

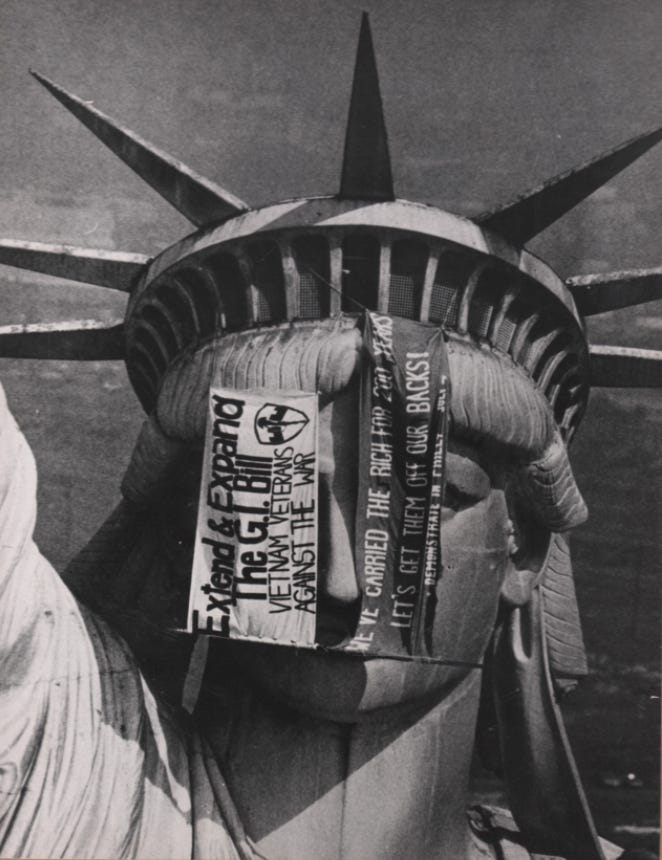

Anti-war protesting: then and now

Noam Chomsky argues the working class were the most prominent early movers against Vietnam — the folks who were doing most of the fighting and dying. It wasn’t the academics or even the students until later. And who am I to argue? Anyway, here’s a piece from Compact lamenting the failure of the current crop of anti-Israel activists to build bridges with the working class and veterans. And that’s an arresting picture of Lady Liberty.

[T]wo key elements are missing from “Biden’s Vietnam” … veterans and the working class. [U]nlike during the Vietnam War … there has been considerably less organized opposition from those not living near a quad. …

A wide swath of American society organized against the war in Vietnam, from the Labor for Peace organization, which included 35 international unions, to the 30,000-member-strong Vietnam Veterans Against the War. The latter group included presidential candidate-to-be John Kerry, then a 27-year-old former Navy lieutenant, who, on April 21, 1971, told a Senate committee that America had created “a monster in the form of millions of men who have been taught to deal and to trade in violence. And who were given the chance to die for the biggest nothing in history.”

Kerry was one of over 1,000 veterans who descended upon Washington, D.C. that year to protest the war. They marched to Arlington Cemetery, organized a sit-in at the Supreme Court, and demanded that the court’s justices “rule on the constitutionality of the Vietnam War.” A few days later, a crowd of somewhere between 175,000 and 500,000 demonstrators joined the veterans, making it the largest protest against an American war the nation had ever witnessed. A poll conducted by the Washington Post found that only about 23 percent of the crowd considered themselves radicals. The rest were liberals, moderates, independents—even a small number of conservatives. …

Throughout American history, many workers and trade unionists have opposed US participation in wars, including World War I, which the AFL and other unions condemned in 1914.

To be sure, big labor unions didn’t present a united front against the [Vietnam] war and often demonized protestors within their ranks. But … In June 1972, almost 1,000 delegates from 35 international unions, including Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta from the United Farm Workers, met at the Teamsters’s Hall in St. Louis to organize against Vietnam. “As men and women of labor who treasure our country’s heritage and future,” they proclaimed their “responsibility to harness every effort to end the war now.”

A large contingent of student radicals also realized that real change in US foreign policy wasn’t possible without a working-class coalition. Some SDS and Columbia activists distributed a leaflet telling students to “build ties with workers” to “unite with those who have the power” to end the war.

That coalition proved to be a flimsy one, but it’s more than the Columbia student protesters of 2024 have to say about the working class or veterans. Today’s campus agitators are right to speak out against the slaughter of Palestinian civilians, but they’re too often doing so in the bloodless academic language of anti-Americanism. For now, members of the New New Left seemingly prefer to find solidarity with each other—and sometimes Hamas—than Americans living off-campus.

Other things being equal: The PC’s ‘oops’ moment

Of course raising jobseeker is ‘fiscally sustainable’

Greg Jericho takes exception to the Productivity Commission’s snapshot of inequality report. To be fair to the Commission, it understands the point Jericho makes. In saying that it was ‘fiscally unsustainable’ to continue with the increased payments introduced during COVID it intends to imply the expression ‘other things being equal’. But this is also being too fair to the Commission. Plenty of ideological work happens between the lines where some things are implied and others are not.

As Jericho says, it might equally have said that superannuation tax concessions are unsustainable. Quite. And had someone drafted it within the Commission, one of the higher-ups would have picked it up. This is how the most effective ideological work is done — between the lines.

As a “snapshot”, the report is just presenting the current situation rather than offering solutions. But unfortunately, it also perpetuates the lie that inequality and poverty is beyond our ability to fix.

The Productivity Commission states with a misguided certainty that only comes from a lifetime of adherence to the God of small government and market forces that these payments were “not fiscally sustainable in the long term”.

Excuse me?

Not fiscally sustainable? Sorry, but that is just flat out wrong. And irresponsibly so.

There is no budgetary or economic reason that makes increasing jobseeker (or other payments) by $550 “not fiscally sustainable”.

Let’s do some comparisons.

In 2024-25, the government is expected to forgo $28bn in revenue because of tax concessions on superannuation contributions, $15.2bn of which goes to the top 20% of income earners. The government will also forgo $21.3bn through tax concessions for superannuation earnings, $12.1bn of which goes to the top 20%.

I await the commission suggesting this is fiscally unsustainable.

It also costs the government $15.5bn to provide a 50% capital gains discount – and $13.6bn of that goes to the richest 20%. Fiscally unsustainable?

Next year the government has budgeted to provide $10.2bn in fuel tax credits, the vast majority of which goes to mining companies – hardly those who are doing it tough. But not fiscally unsustainable it seems.

So how much would it cost to raise jobseeker by $550 a fortnight?

Using the Parliamentary Budget Office’s build your own budget tool, we can calculate that it would cost about $9.7bn next year.

Speaking of inequality …

Who is this man? Keep an eye out for him below. He helped us think about inequality. And he wanted the rich to pay for WWI. The other guy won a silver medal at the Olympics. But this is all ahead of you as you read on.

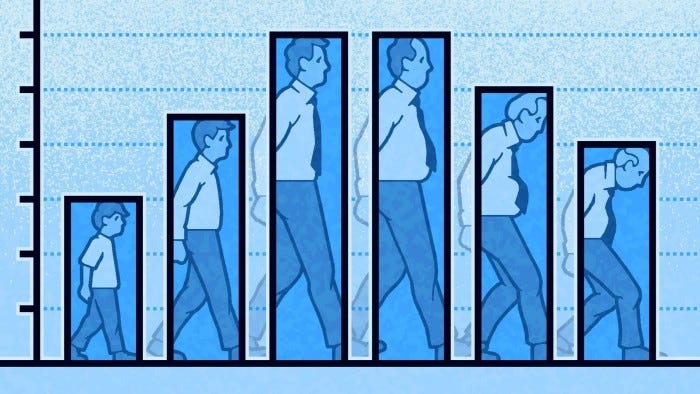

Martin Wolf on ageing

Is aging a problem or an opportunity? It’s both of course, but what comes through in this dramatic summary of the evidence is that things need to be rethought. We need to make those clichés about lifelong learning and movement in and out of the workforce realities. In Australia, it means rethinking our superannuation system. There’s never been a good reason for limiting it to retirement savings. One should have access to it for other legitimate reasons for accessing one’s savings, like buying one’s first home and retraining. The perfect way to do it would be to integrate three changes over time.

Remove tax concessions to make it fairer and more sensible. If you use compulsion as we do, why use another much costlier mechanism — tax concessions?

Increase the rate of contributions over time (partly to compensate for 1 — which leaves money for tax cuts to take-home pay — and partly to fund capital needs other than retirement.)

Allow access to one’s super for those legitimate needs for access to one’s savings other than retirement income.

I call it Singapore light.

In the UK in 1965, the most common age of death was in the first year of life. Today the most common age to die is 87 years old. This startling statistic comes from a remarkable new book, The Longevity Imperative, by Andrew Scott. …

But we are living longer everywhere: global life expectancy is now 76 for women and 71 for men (clearly, the weaker sex). This new world has been created by the collapse in death rates of the young. Back in 1841, 35 per cent of male children were dead before they reached 20 in the UK and 77 per cent did not survive to 70. By 2020, these figures had fallen to 0.7 and 21 per cent, respectively.

Yes, the new world we live in creates challenges. But the crucial point Scott makes is that it also creates opportunities. We need to rethink old age, as individuals and societies. We must not shuffle a huge proportion of our society into unproductive and unhealthy “old age”. We can and must do far better, both individually and socially. This is his “imperative”. …

[C]learly, a world in which most are likely to live into their 90s, many even longer, needs to be thoroughly rethought. The idea of 25 or so years of education, 35 years of work and then, say, 35 years of retirement is impossible, for both individuals and society. It is certainly unaffordable. It is also likely to produce an empty old age for vast proportions of the population.

It is going to be necessary to work longer as a matter of course. This is also going to require several changes in one’s career over a lifetime. Instead of one period of education, one of work and one of retirement, it will make sense for people to mix the three up. People will go back to study, repeatedly. They will take breaks, repeatedly. They will change what they do, repeatedly. This is the way to make longevity affordable and, as important, bearable. To make such a world work, we will have to reorganise education, work, pensions, welfare states and health systems. People will no longer, for example, go to university or receive training only as young adults. This will be a lifetime activity. Again, mandatory or standard retirement ages will be senseless. People must be given options to work and not to do so at various stages of their lives. Just raising retirement ages all round is both inefficient and inequitable since life expectancy is so unevenly distributed. Contribution rates to pensions will also need to be changed. Today they are generally too low. Health systems must also fully incorporate public health, which will become ever more important as society ages. We are moving into a new, old world. This is the fruit of a huge success. Yet there is also a realistic danger of a Struldbrugg future for individuals and society. If so, we must rethink our view on the priority of preserving life.

A little culture clash

Andy Haldane on what’s holding us back

The very terrific Andy Haldane alerts us to a new threat. The extent to which risk-aversion has risen in our economy. Or is that threat an old one? He cites Keynes idea of the paradox of thrift and compares it with a paradox of risk. The paradox of risk has similar characteristics, but then again they both bleed into one another. In Keynes’s thinking, imbalances between savings and investment led to economic cycles. If there was a slump it was coincident with savings exceeding investment — or an inadequate appetite for risk.

Haldane is clearly suggesting some distinction between the two and suggesting that one can target policy action around raising the appetite for risk. He gives the example of financial regulation, but I wonder where a more systematic approach to risk might lead.

I can’t say I’ve ever answered this in a systematic way, but I do recall when I was on the Cutler Review into Innovation in 2008 I argued that government contributions to innovation, particularly subsidising early stage capital formation — should be countercyclical. That is, we should dole out much larger government contributions to those schemes in downturns because a number of stars aligned. The opportunity cost of the money was low, any equity the government purchased as a result would be purchased cheaply and it would make a small contribution to getting us out of the slump. And vice versa when things were booming. The market is far more cyclical in early stage capital than in finance generally. Anyway, everyone agreed that they hadn’t heard this idea before which meant that it could be safely ignored. True we were trying to promote innovation, but only if it was the kind of innovation that we’d seen a fair bit of before. So I retreated, showing what magnanimity I could at their sagacity, and kept my powder dry for other battles.

The Great Crash of 1929 left lasting scars on investors’ balance sheets and risk appetites. These scars, financial and psychological, gave rise to what John Maynard Keynes called the “paradox of thrift” — the paradox being that an individually virtuous act (greater saving) was collectively calamitous (economic slump). [T]his paradox ushered in the Great Depression. Almost a century on, those same behaviours are in play today.

Risk-aversion is rife among workers, businesses and governments. Security is trumping opportunity. Economies face a “paradox of risk” — in seeking to avoid risks, we are amplifying them. Rules and regulations put in place to curb risk are having the same, paradoxical, impact. Recent shocks to the world economy have come in an elongated sequence — from the financial crisis to Covid, the cost of living shock to geopolitical tensions.

The scars have been compounding, leaving too little time for balance sheets or risk appetites to be repaired. Such psychological scarring generates a defensive mindset. Facing uncertainty, the instinctive response of business is to defer investment decisions, especially large-scale ones involving capital and people. …

One measure of this is the combined rate of job creation and destruction — the reallocation rate. Since the start of the century, this has fallen sharply across most OECD countries and most sectors. …

This has resulted in a lengthening tail of low productivity companies, surviving but not thriving. … A generation ago, business lending was a third of UK pension funds’ assets. Today it is less than 2 per cent. There has been no new net lending to UK companies by UK banks since 2008. Depriving fast-growing companies of finance has also damped dynamism. Non-traditional investors, including venture capital, private equity and sovereign wealth fund investors, have filled some of the gap. But uncertainty is now causing many of them to retreat as well.

This defensive behaviour has now reached governments. They have run large deficits to protect economies from the effects of recent shocks, causing public debt in the G7 to rise to more than 100 per cent of GDP. Many are now beating a retreat, leaving fiscal policy a drag on growth in the US, UK and euro-area. This all adds to future macroeconomic uncertainty, 1930s-style.

Can anything be done? Having diagnosed the paradox of thrift a century ago, Keynes also prescribed a solution. Government is the agent best able to bear long-term risk. It is well placed to act as a patient venture capitalist, investing where others fear to tread. Doing so helps heal the private sector’s scars and stir their animal spirits.

In the 1930s in the UK and US, this recipe worked. But repeating it today is hindered by debt-first fiscal rules in many countries. By constraining investment and stunting growth, these are self-defeating. To resolve the paradox, they need to be replaced with rules that prioritise growth and seek to maximise national net worth, not minimise gross debt.

The same logic applies to the rules shaping risk in private markets. The Basel III regulatory rules for banks, and the Solvency II rules for insurance companies, were crafted in an era when risk was too high, and were successful in encouraging a retreat. But today’s risk problem is too little, not too much.

The Youtube algorithm has taken to feeding me snippets of Richard Nixon. And I have to admit to finding him rather fetching. He was the only president in his generation who wasn’t rich.

Normandie: The greatest art-deco object ever created?

That’s the conclusion at the end of a doco I happened upon on SBS on Demand. I got a bit fascinated in trans-atlantic liners when I was a kid. And did they say ‘blue ribband’ and not ‘blue ribbon’? Well, yes they did. But why?

And there was one I didn’t know much about. In many ways, it was the greatest of them all. So here are some pics for your delectation.

J. M. Barrie on Bullshit

From a commencement address at St Andrews in 1922.

Your betters had no share in the immediate cause of the war; we know what nation has that blot to wipe out; but for fifty years or so we heeded not the rumblings of the distant drum, I do not mean by lack of military preparations; and when war did come we told youth, who had to get us out of it, tall tales of what it really is and of the clover beds to which it leads.

We were not meaning to deceive, most of us were as honourable and as ignorant as the youth themselves; but that does not acquit us of failings such as stupidity and jealousy, the two black spots in human nature which, more than love of money, are at the root of all evil. If you prefer to leave things as they are we shall probably fail you again. Do not be too sure that we have learned our lesson, and are not at this very moment doddering down some brimstone path.

And apropos of the Very Serious People

Another sure way to fame is to know what you mean. It is a solemn thought that almost no one--if he is truly eminent--knows what he means. Look at the great ones of the earth, the politicians. We do not discuss what they say, but what they may have meant when they said it. In 1922 we are all wondering, and so are they, what they meant in 1914 and afterwards. They are publishing books trying to find out; the men of action as well as the men of words. There are exceptions. It is not that our statesmen are 'sugared mouths with minds therefrae'; many of them are the best men we have got, upright and anxious, nothing cheaper than to miscall them. The explanation seems just to be that it is so difficult to know what you mean, especially when you have become a swell. No longer apparently can you deal in 'russet yeas and honest kersey noes'; gone for ever is simplicity, which is as beautiful as the divine plain face of Lamb's Miss Kelly. Doubts breed suspicions, a dangerous air. Without suspicion there might have been no war. When you are called to Downing Street to discuss what you want of your betters with the Prime Minister he won't be suspicious, not as far as you can see; but remember the atmosphere of generations you are in, and when he passes you the toast-rack say to yourselves, if you would be in the mode, 'Now, I wonder what he means by that.'

Speaking of not knowing what you’re talking about:

The minister on the pre and post commonsense eras

LOL

The Origins of the Investment Theory of Party Competition

Here’s the preface to the Japanese edition of The Golden Rule by Thomas Ferguson — the Golden Rule being that those people with the gold make the rules. The original book was published back in the mid 1990s but it’s basic thesis is still going strong.

The heart of Golden Rule is its presentation of the investment theory of party competition. This developed out of a crucial formative experience of mine as a graduate student at Princeton University in the mid-seventies. At that time in economics and political science, mathematical models of party competition were all the rage. As Golden Rule discusses at length, these models purport to show how citizens control the direction of government policy by voting in contested elections. I did not believe this claim: the surging power of money, now obvious in the United States (and many other countries) – was already plain to me, but I was struggling to put my finger on the flaws in the standard models.

An adviser remarked to me that Ivy Lee’s papers were over at Seeley Mudd Library, Princeton’s principal archive for collections of private papers. … I knew he had been a principal adviser to John D. Rockefeller, Sr., and many enterprises related to the billionaire. I had never consulted an archive – that was simply not done in either political science or economics at that time, but with an eye to finding some inspiration for my Ph.D. thesis, I decided to go take a look.

Within minutes I had dredged up a memorandum by Lee on his conversation with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the turbulent late fall of 1933. At the time, the dollar was still floating (really: sinking) in the wake of the President’s decision to abandon the gold standard and ramp up the First New Deal’s National Recovery Administration. What shocked me was the directness and clarity with which Roosevelt discussed his international economic policy aims. Nothing I had read or heard on the New Deal prepared me for this. The customary view … was that top Roosevelt administration policymakers had very little idea about what they were doing. Their experts may have, but not the policymakers. …

Lee’s memorandum exposed the hollowness of that claim. … Two other features of the memo also stood out. Roosevelt’s matter-of-fact allusions to conversations with many other top business leaders and the use Ivy Lee made of his own memo. The President was obviously engaged in a constant dialog with prominent business leaders about the progress of his programs. …

Golden Rule’s analysis of this problem highlights the crucial interaction between social class and industrial structures. It flatly rejects notions that party systems are “normally” defined by conflicts between business and labor parties. That happens only if labor is fairly organized and strong. Short of that, divisions within the business community, especially over international trade and sometimes public investment, emerge and drive the party system. …

Where investment and organization by average citizens are weak, however, power passes by default to major investor groups, which can far more easily bear the costs of contending for control of the state. …

Alas, today, as one contemplates the vast increases in economic inequality in most formally democratic countries, it is necessary to ask whether the United States and similar countries are not sliding into a new form of “affluent authoritarianism.” …

So far, social scientists play with these devastating findings like cats with balls of yarn. They seem unable to metabolize them or build upon them. Instead, they keep repeating variations on old themes and stay fixated on opinion. If average voters are unimportant, they want to identify some precise stratum of opinion that is – perhaps the most affluent 10% of all voters, the top 2%, or even the famous 1%.

But as I have emphasized in work published since Golden Rule, the idea that any stratum of “opinion” holds the key to policy is delusory. Surveys of policy views held by the 1% or 2%, or even the top 10% of voters, especially if they are trying to explain changes in policy, do not typically reflect anything as innocently vaporous as “opinion” at all. Their data are instead noisy by-products of the mobilization of big money with its comet-like trail of social networks, subsidized op-eds, subservient think tanks, and journalists seeking applause and better positions. That is how the reality of money-driven political systems shows up in surveys.

“The Calf-Path” by Sam Walter Foss:

Picked up from a comment on Substack

One day, through the primeval wood,

A calf walked home, as good calves should;

But made a trail all bent askew,

A crooked trail as all calves do.

Since then two hundred years have fled,

And, I infer, the calf is dead.

But still he left behind his trail,

And thereby hangs my moral tale.

The trail was taken up next day

By a lone dog that passed that way;

And then a wise bell-wether sheep

Pursued the trail o’er vale and steep,

And drew the flock behind him, too,

As good bell-wethers always do.

And from that day, o’er hill and glade,

Through those old woods a path was made;

And many men wound in and out,

And dodged, and turned, and bent about

And uttered words of righteous wrath

Because ‘twas such a crooked path.

But still they followed -- do not laugh --

The first migrations of that calf,

And through this winding wood-way stalked,

Because he wobbled when he walked.

This forest path became a lane,

That bent, and turned, and turned again;

This crooked lane became a road,

Where many a poor horse with his load

Toiled on beneath the burning sun,

And traveled some three miles in one.

And thus a century and a half

They trod the footsteps of that calf.

The years passed on in swiftness fleet,

The road became a village street,

And this, before men were aware,

A city’s crowded thoroughfare;

And soon the central street was this

Of a renowned metropolis;

And men two centuries and a half

Trod in the footsteps of that calf.

Each day a hundred thousand rout

Followed the zigzag calf about;

And o’er his crooked journey went

The traffic of a continent.

A hundred thousand men were led

By one calf near three centuries dead.

They followed still his crooked way,

And lost one hundred years a day;

For thus such reverence is lent

To well-established precedent.

A moral lesson this might teach,

Were I ordained and called to preach;

For men are prone to go it blind

Along the calf-paths of the mind,

And work away from sun to sun

To do what other men have done.

They follow in the beaten track,

And out and in, and forth and back,

And still their devious course pursue,

To keep the path that others do.

But how the wise old wood-gods laugh,

Who saw the first primeval calf!

Ah! many things this tale might teach --

But I am not ordained to preach.

The good old days

Heaviosity half hour

A. C. Pigou on the war, and how to pay for it

I’m currently reading a biography of the economist Arthur Cecil Pigou who succeeded Marshall at Cambridge and was something of a rival to Keynes. He developed the theory of externalities and also the economics of welfare and income distribution.

Cambridge itself was radically transformed by the war. In 1910, 3,699 male undergraduate students were enrolled in the university. Just weeks after the war started, that number had fallen off by nearly half. By the spring of 1916, there were only 575 male under-graduates in residence.22 For a time, students were replaced by soldiers and patients. Cambridge hosted the 6th Division of the British Expeditionary Force, the unit’s encampment spreading over the surrounding fields all the way to the outlying village of Grantchester. Soon, parts of Trinity College were transformed into a military hospital, as was the King’s cricket ground, with a block of King’s itself used to house the nurses.23 Though not without pockets of dissent, Cambridge, like the rest of Britain, was mobilized in a burst of patriotic fervor that would wane only as the war dragged on.24 By 1915, the town felt deserted. Everyone had gone to France.

When Britain initiated conscription under the Military Service Act in early 1916, Pigou, as an unmarried thirty-nine-year-old, was eligible for the draft. Yet Pigou was neither called up, nor did he join the ranks of conscientious objectors, a group highly stigmatized in British society, including by some of his colleagues.25 As a teacher at Cambridge, Pigou was exempted from service, but only after it was argued by John Neville Keynes and others that his presence at Cambridge was indispensable, and that, due to other teachers being called to London, it would be “quite impossible” to carry on teaching economics without him.26 The older Keynes’s advocacy spared Pigou from military service, but it also bound Pigou to his teaching, despite his desire to return to the ambulance corps, in which he was decorated for valor.27 He also briefly bowed to pressure to join the war effort as an economist, though he was less involved than many of his colleagues. Along with academics from other British universities, he authored a report for the Board of Trade, working part time from Cambridge as an advisor to the government on postwar employment and the reemployment of demobilized soldiers reentering the labor force.28 Resistance to national wartime policy was not uncommon among progressive Liberals, many of whom were deeply uncomfortable with the prime minister, David Lloyd George, conscription, and the war itself.29 Still, Pigou’s sentiments put him distinctly out of step with popular sentiment. In an unpublished manuscript, he wrote that he had “been informed by one correspondent that, having thus proved myself a traitor to my country ought to be ‘deported or shot with the least possible delay.’”30 He later quoted another “brief and to the point” message he received: “May you rot for ever in the lowest cesspools of Hell!”31

His convictions hurt him professionally as well, repeatedly derailing his election to the British Academy.32 In contrast, Pigou’s brother had excelled in his rise through the ranks of the Royal Navy. By the armistice in 1918, he was a commander and had been placed in charge of a cruiser.33 By a similar series of events, his brother-in-law, Arthur Hugh Oldham, also became the acting captain of a battle-cruiser.34 Alfred Marshall, despite his own sympathy for German culture and his love of “the Germans through it all,” also supported British belligerence.35 Yet despite social, as well as likely personal and familial pressure, Pigou did not budge in his opposition to the war. In 1919, well after Germany had surrendered and Britain was basking in victory, he signed his name to a petition of notable individuals directed to Lloyd George on behalf of imprisoned conscientious objectors.36

The reasons for Pigou’s opposition were spelled out in an unpublished manuscript written sometime between late 1915 and early 1916, after he had experienced war firsthand but before it had been decided whether he would be conscripted. Pigou explained his reticence, first in logical terms and then in more emotive language. He begged his would-be audience to recognize that the present war, like all wars, had become a “war of passion. . . . In the rich soil of an abysmal ignorance . . . [prejudice] scatters abundant seed.”37 Pigou decried the popular desire to punish Germany for atrocities “by another defeat on the field of battle.” Employing stark, consequentialist language, he noted, “to anyone who reflects philosophically upon the matter to-day, it must be plain that mere revenge for its own sake and apart from its effects . . . is not a thing . . . [man] ought to pursue.” Victory in the war would no longer serve as either a deterrent or a moral lesson for the Germans, since, for Pigou, by continuing the bloodshed, the Allies had already lost the moral high ground.38 He also dismissed the promise of reparations as a justification for continued fighting. From a strictly economic standpoint, the cost of the war far outweighed the economic advantage of reparations. Yet, in the end, Pigou’s most fundamental argument against the war did not make use of economics or even the cool rationality with which he dispatched popular justifications. Instead, he conjured the horrors of war, horrors that he himself had witnessed: the abject suffering and the loss of life:

This to any humane mind must surely be conclusive—in the gamble . . . [of war], the stakes with which warring nations play are human lives. Any man, be he statesman, journalist or simple citizen, who, in the hope of thereby winning an indemnity for his county, would cause the war to be prolonged by a week or by a day is bartering for money the blood of generous youths. How much agony in wounds and in disease, what array of homeless fugitives, what tale of widowed women, fatherless children, desolated friends, shall we balance against the chance of a penny off the income tax? That question it is an insult to ask.39

In “Terms of Peace,” Pigou drew a vividly clear line between economic welfare and general welfare. In the face of so much human suffering, he found even the thought of reparations as a justification for war’s continuation an insult. Some things were simply not meant to be brought into line with the measuring rod of money. It would be repugnant to value a human life, much less thousands or millions of lives, in monetary terms.

There was a profound humanity in Pigou’s words. The war was perhaps the first time that he would have come into close personal contact with the “men in the street,” to whom he had long condescended. The Ambulance Unit, though predominantly middle class, was composed of men from a range of social backgrounds, with “the poorest members drawing a small maintenance allowance from a special fund.”40 And, of course, Pigou would have been inter-acting every day with wounded and dying soldiers from across Britain and the empire. Coming face to face with “common men” in these circumstances, his reaction was deep and strong. In a rare burst of emotion, Pigou evoked of the power of unifying human experience: a reminder that pain, loss, and death affected all alike.

The war did not stop Pigou from thinking about economics or economic policy.41 In fact, as will be discussed later, he published an important piece on the quantity theory of money in 1917.42 War worked to further infuse Pigou’s economics with both a concern for social issues as well as a fury that liberated him from his otherwise tempered positivistic objectivity. Though other economists, including the retired Marshall, wrote about the importance of capital and steeply graduated income taxes to equitably pay for the war, few were as direct or forceful as Pigou, especially on the topic of distributing the tax burden.43 Sickened not only by the fighting itself but also by the hawkishness of the rich, he suggested in the pages of journals and magazines a massive capital levy aimed at the very wealthy in order to pay for the war once and for all, a proposal that had also been made by organs of the left, including the Trades Union Congress.44 There was to be some justice, he suggested, in making those who decided that Britain should go to war pay for it instead of shouldering the innocents of future generations with a massive debt obligation—something he discussed in a Quarterly Journal of Economics article titled “The Burden of War and Future Generations.”45 It was not just the interest of the unborn that Pigou sought to safeguard. In one version of his proposal, printed in The Economist, he called for taxing individuals not at a percentage of their income, but so as to leave all people with the same income: “if a man with an income of £1,000 has to pay £500, one with an income of £100,000 should pay, not £50,000 or even £80,000, but £99,500.”46 For Pigou, the tax was appropriate as a wartime measure not on economic grounds but on ethical ones. And those grounds were rooted in principles of justice and equality. As he wrote in The Economist:

In this war young men are being asked to sacrifice—the strong and the weak together, those with full lives and those with little to live for—not equal fractions of their well-being, but the whole of what they possess. If this, in war, is the right principle to apply to the lives of men, it is also the right principle to apply to their money.47

The argument for the tax stressed the importance of making the war hurt, not only for the poor who were invariably drafted, but also for the rich, through their pocketbooks. Pigou recognized that such a levy would not be enacted. “I do not, of course,” he wrote, “pretend that an arrangement of this kind could be practically established. But it illustrates the principle and the ideal towards which it is the duty of the government to approach.”48

In a different piece, not published but written before the end of the war, Pigou argued that the levy should take the form of a tax on wealth, not income, but as in the case of the tax proposed in The Economist, asserted that it should penalize the rich, who might have had low incomes but valuable holdings, more than it would the poor. Again, the result was that all would suffer together in comparable measure. “To impose such a levy,” he wrote, “is not merely not unfair, but considerations of fairness directly demand it.” And, here in this implausible theoretical case, it was clear that the state was to be the instrument of rectitude. This unpublished typescript bore the original title of “The War Debt and the Consumption of Wealth,” which Pigou had crossed out and over which he had written by hand the new title, “A Capital Levy after the War,” much more obviously a policy suggestion.49

Whatever happened to cybernetics?

Extract from The Unaccountability Machine

I’ve always wondered what happened to Stafford Beer’s cybernetics. He was all the rage when the socialist leader of Chile commissioned him to make the Chilean economy work. It would likely have ended in tears in one way or another, but it ended with Augusto Pinochet’s coup. Out with Mr Beer and in with Messers Hayek and Friedman. Anyway, I came across this nice explanation for the two ‘wings’ of cybernetics. One was destined to prosper as the handmaiden to the IT revolution. The other one was trying to help us understand much subtler, more complex things. It has languished.

How to Psychoanalyse a Non-human Intelligence

I have an uneasy feeling, for instance, that if the computer had been around at the time of Copernicus, nobody would have ever bothered with him, because the computers could have handled the Ptolemaic epicycles with perfect ease.

Kenneth Boulding, ‘The Economics of Knowledge and the Knowledge of Economics’, 1966

One of the reasons why so many of the cyberneticians were hospitable to Stafford Beer might have been that he was doing the kind of cybernetics that they’d been hoping for. Because even quite early in the project, things had gone somewhat off the rails. Cybernetics had been conceived as an interdisciplinary project, with a very large input from the medical and social sciences. But it got unbalanced really quickly. People were just too good at inventing transistors.

Tremors and ataxia in automated gunsights

Norbert Wiener had first thought about control systems in the context of his war work. One of his projects at the US government’s Office of Scientific Research and Development was to invent an automated gun sight that could predict the movement of an enemy aeroplane and ‘aim off’ sufficiently to compensate for its likely movement while the bullet was in flight. Simply extrapolating along a straight line in the direction that the plane was heading wasn’t working, as pilots would be taking evasive action. But Wiener and his team realised that the planes’ movement couldn’t be random. There were limits on the sharpness of turns that could be made, because of the need to maintain structural integrity of the airframe and continued consciousness of the pilot.

The set of manoeuvres that pilots used was an even smaller subset of the theoretically possible stunts. Flying an air raid was itself a hugely stressful task, leaving only a small amount of mental bandwidth for evading ground fire. So, pilots tended to make spur-of-the-moment choices from a small number of techniques; in principle, a manoeuvre might be identified from its earliest stages and the rest of the trajectory predicted. All that remained was the task of fitting a mathematical curve to the trajectory and transferring this information to the servomotors of the gun turret.

This turned into a problem of feedback; the gunsight moved, which meant that its input changed, which meant that it moved again. Quickly, Wiener found that the system had a tendency to develop two kinds of problems. Either the feedback was too weak, leaving the gun trailing behind its target, or it was too strong, and the gun oscillated around the target, overcorrecting its errors in one direction and then the other.

A friend who was a medical doctor encouraged Wiener to interpret these problems as equivalent to two symptoms of injury to the cerebellum – ataxia, and the ‘purpose tremor’. This, arguably, was the moment at which the projects of control engineering, feedback and communication theory became distinctively ‘cybernetics’. The idea had been born that a common quantity was preserved between the radar, the computing machine, the servomotors and the human gunner.

All the wonderful things

This quantity was, of course, ‘information’ – the subject of the socialist planning debate, but in a context where it might be quantified and turned into the subject of rigorous theory. And for many other scientists, partly because war work had thrown them into the company of people in other fields, it seemed like it might be the key to another scientific revolution. After all, as well as gunsights and commodity markets, information was the stuff of the human brain. It was what people wrote down in books, what organised individuals into societies, the stuff of thought itself. By 1945, dozens of people – telephone engineers, brain doctors, ecologists, anthropologists, philosophers, physicists – had bottom desk drawers bulging with ideas that had come to them when they were working on breaking codes, treating shell shock, designing radar consoles or, in Stafford Beer’s case, mapping relations between tribal factions. They wanted to keep talking about them.

And so they did. In Britain, there was the Ratio Club, whose members included Alan Turing, while in America the Macy conferences* invited Wiener and John von Neumann, as well as the anthropologists Geoffrey Bateson and Margaret Mead. People made light-seeking robots called ‘tortoises’ and observed that they could get into pathological states that resembled ‘depression’ or ‘compulsive disorder’. They built mice that could find their way through mazes and ‘homeostats’ that could find their way back to a balanced state when their equilibrium was disturbed. And they drank, smoked cigars and argued. Over dinners and in seminars, it was a rare moment when people were both making rapid progress in mathematics and trying to think about the practical implications. Wiener’s Cybernetics gives a flavour of how things were in 1948; the first chapter, ‘Newtonian and Bergsonian Time’, consists of a philosophical speculation on the nature of consciousness; the second is called ‘Groups and Statistical Mechanics’ and has several pages covered with nothing but equations. Unfortunately, the project failed.

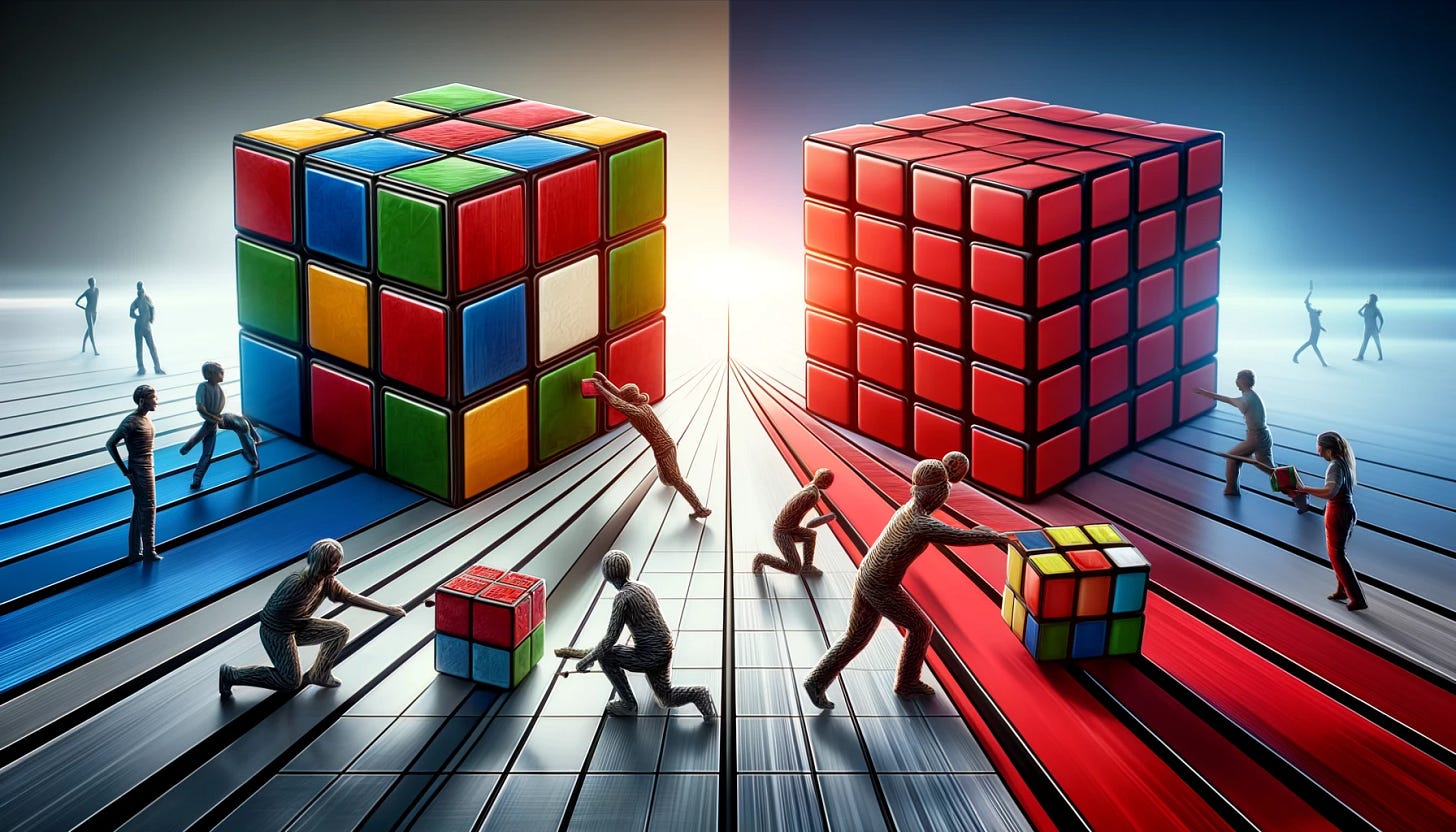

The sad demise of the Cube-turning Society

This might be considered an unreasonable assessment on my part. After all, the members of the Ratio Club and the attendees of the Macy conferences between them invented information theory, the architecture of the microprocessor, digital computation and a large proportion of everything that makes up the modern world. Without the intellectual explosion in computing and information technology that took place at the end of the Second World War, life today would be unimaginably different.

But very little of their progress was in the field of cybernetics. What happened was that in trying to solve the problems of ‘control and communication in the animal and the machine’, people had ideas that were applicable to other problems. The solutions to these problems helped them design fantastic new machines, things which had commercial applications beyond the demonstration of simple ideas about control and representation. And within a decade or so – basically the period between the first edition of Wiener’s Cybernetics in 1948 and the second in 1961 – most of the effort had been diverted towards the new and useful technological projects of computation and telecommunications.

What happened? Here’s an analogy. Imagine a club of people who are interested in turning cubes ‘the right way up’. In the early days of the cube-turning movement, they start out debating what it means for a cube to be the right way up and how ‘way-upness’ can be manipulated. But they are clever people, and breakthroughs come quickly; pretty soon they get the idea of colouring the cubes’ faces so that they can talk about ‘red side up’, ‘blue side down’ and so on. Within a few years, they have established fundamental theorems about cube orientation, and the society announces a grand symposium, where the leading cube manipulators of the day are to discuss the new science of turning cubes.

Within a year of the symposium, the club is more or less defunct. It turned out that there were two factions within the Cube-turning Society, and that they were interested in different problems. One group was interested in making long lines of cubes, all the same way up. The other group wanted to solve Rubik’s Cube puzzles.

While the question of what constituted the orientation of a cube was live, the two groups could work together. Once that question had been resolved, their underlying difference became acute, because the two problems are not the same. The group that wanted to make long lines of cubes could make rapid progress, because orienting a hundred cubes red-side-up is subject to a simple algorithm,* applied one hundred times.

The Rubik’s Cube group, however, would still be faced with a difficult problem. Colouring the faces of their puzzle would have given them a concept of what a solution might mean. But it doesn’t instantly solve their problem – in fact, it could be argued that it raises a few new questions for them, as they would realise that their original puzzle isn’t actually a stack of twenty-seven cubes but only looks like one. They now have to grapple with the question of whether their original vision of the puzzle as a cube-turning problem was valid. They certainly can’t assume that the strides being made by their former clubmates in developing more efficient ways to arrange lines of red-side-up cubes will be helpful to them.

Philosophers and telephones

This, more or less, was what happened to the science of cybernetics. Some people were interested in information because they wanted to transmit messages from one location to another, or to process strings of bits representing numbers in series of sequential operations. Others were interested in systems with multiple inputs and outputs and complex connections between them – systems like brains (and, when Stafford Beer came along, organisations).

Very quickly, the physicists and engineers realised that the concept of information was related to things that had already been established in the statistical-mechanical interpretation of thermodynamics. In particular, they saw that information was a difference between states – a system in perfect thermal equilibrium had, in some sense, lost its information. Information was therefore related to the concept of entropy, the extent to which energy becomes disordered and unusable as hot things cool down, cold things warm up and the universe tends towards inevitable stasis.

This leap of understanding allowed a great deal of the existing mathematical toolkit of physics to be brought to bear on the problem. A number of key concepts were soon developed, relating to the capacity of a noisy channel to carry a message and methods for error correction. ‘Information theory’ had been born. There were actually two versions of it. In Wiener’s theorem, information was represented by entropy with a negative sign in front of it, and was interpreted as the amount of ‘order’ in a sequence. Claude Shannon of Bell Labs derived the same theorem independently, but in his version there was no negative sign, and information was taken as representing the extent to which a sequence was unpredictable – whether it constituted ‘news’.

Shannon’s version of information theory is the one that more people remember these days; it was more suited to communications and computing, because (among other things) it measures the extent to which a message can be digitally ‘compressed’ to take up less memory space by getting rid of redundancy. Wiener was reasonably generous in allowing the credit for discovery, but stuck with his own formulation and regarded it as philosophically significant.

But the rapid progress in information theory was mainly related to operations that could be carried out bit by bit, one at a time. Progress on complex systems – the initial goal of the cyberneticians – was much slower.

The trouble with complex systems is that combinations of things tend to multiply together rather than adding up, so the number of possible states gets out of control very quickly. Even a Rubik’s Cube has more than 43 quintillion possible states; clearly a brain or an organisation has far more. So one side of the initial cybernetic project was always going to develop far more quickly than the other. Pretty soon, everyone who could find a way to convert their problem into one where the bits of information could be addressed sequentially rather than in combination had done so. And the new science of communication and control was left in the dust, subject to the unfair perception that it hadn’t made much progress.

The philosophers and neurologists were not just hampered by the mathematics of combinations; there was also an element of ‘decisions nobody made’ to the structure of cybernetic research after the war. As we have noted about economics and medicine, some sciences are cursed with the need to answer questions as they arise, rather than in a logical order. For the early cyberneticians – and therefore, for the majority of computer scientists to the present day – crucial, foundational assumptions were built into the discipline in the 1940s, largely because of the war. Wiener came to regret having decided early on that if control systems were to be used for war work, they would need to have a number of practical properties.

They couldn’t depend on accurate measurement, because of the conditions they would be operating under. Information would need to be represented and calculations made digitally (like an abacus) and not in analogue form (like a slide rule). They would probably need to be implemented in electronic rather than mechanical form; electronic switches could be operated more quickly and would not wear out. This in turn meant that numbers would need to be represented as binary digits (later known as ‘bits’). And since every occasion on which information was input by a human being or output for human understanding would slow the process down and introduce opportunities for errors, as much of the process as possible had to be put on to the machine.

These decisions meant that research into other kinds of computing would move more slowly, with the pace of improvement in digital electronic computing sped along by the progress of the electronics industry in making cheaper and smaller switches to represent the binary codes. It also meant that the research programme would concentrate on automating what could be automated rather than redesigning whole processes; calculating machines would be dropped into existing organisational structures as tools to speed up tasks that were already being carried out.

It is hard to say that these were the wrong decisions – transistor miniaturisation progressed faster than anyone expected, as did the introduction of computers into industry and government. But many people who had been involved in cybernetics seemed to think of it as a missed opportunity; Stafford Beer used to say that the way in which computers were used in the 1970s was as if companies had recruited the greatest geniuses of humanity, before setting them to work memorising the phone book to save a few seconds turning pages.

Interesting comments about Stafford Beer (1926-2002) whose writings about Cybernetics and Management I once read but had almost completely forgotten.