Can the centre hold?

Hint: no, not unless we do better than the 1930s

As I’ve watched masked men kidnapping people off the streets in the US, watched the craze for replacing a flawed democracy with a CEO grow from a fringe to capturing a a substantial faction of the most powerful people in the US (and a majority of the Supreme Court), a new kind of urgency has come over me. This came out when Peter Clarke interviewed me a few weeks ago. He runs The Transit Zone podcast with Margo Kingston and, as you’ll hear, thinks interviewing is an important part of our democracy. So do I. Anyway, I was very happy with the interview, and expect that’s attributable to his skill.

In any event, this interview represents a bit of a change of register for me; one that I think is much better suited to our times. I suggest that introducing representation by lottery into our political system (juries are already entrenched in our judicial systems) is the only way I can think of, of rescuing democracy from the fate we can see playing out in the US.

Given that, and having finished releasing Part One of the video series last week, I thought I’d pause the video releases and start Part Two next week.

The Death of the Conservative Prestige Economy

The often excellent Geoff Shullenberger being excellent again! In 2013 Peter Mair published Ruling the void making “hollowing out” an expression du jour for understanding what had gone wrong with democracy. Political parties had gone from being important organs of community representation to being brand managers staffed by apparatchiks. But if you look around, ‘hollowing out’ is a term that could be applied to more and more aspects of our society. Shullenberger summarises just one. I hope to publish more on this soon.

Earlier this week, in a discussion of the recent Heritage Foundation brouhaha over the Tucker Carlson-Nick Fuentes interview, John Ganz wrote that “the Republican Party and the right-wing apparatus in general have become totally dominated by propaganda and propagandists. Important roles that once would go to professionals or at least politicians now go to podcasters and talking heads.” He cited the Trump administration’s elevation of figures like Pete Hegseth and Kash Patel to illustrate the point. His conclusion was that this indicated the “hollowing out” of the GOP, which increasingly functions as “a career opportunity for agitators and propagandists.”

Shortly after reading this, I noticed an announcement that the Manhattan Institute’s magazine City Journal will be awarding its annual award to Daily Wire founder Ben Shapiro. The thing that struck me about it was that the choice of recipient resembled former establishment insider Carlson’s strategy of chasing relevance by inviting increasingly lowbrow online influencers onto his show. Shapiro shares the old GOP establishment’s foreign policy preferences, but like Fuentes, he is also a media entrepreneur who hasn’t depended on the conservative establishment for his profile and career. Instead, he has cultivated an audience directly, as a commercially viable player in the attention economy.

Prizes often carry monetary rewards, but they should be understood as tokens in an economy distinct from the real economy, in which the primary currency isn’t money but prestige. This is the subject of James English’s 2008 book, The Economy of Prestige, which explores the history and sociology of literary prizes and awards and the function they serve in the “circulation of cultural capital,” Pierre Bourdieu’s term for the elusive commodity cultural actors accumulate when they achieve higher levels of renown.

A guiding principle of a properly functioning prestige economy is that the optimal awardee must need the awarding institution more than the other way around. The Nobel Prize in literature illustrates this point: its typical and expected function is to consecrate figures of national or regional renown on a global scale, admitting them into a select international pantheon...

The conservative prize ecosystem historically often went to conservative movement intellectuals attached to think tanks in the same ecosystem: people like Charles Murray, Amity Shlaes, and Heather Mac Donald. They are part of the apparatus by which conservatism has maintained a parallel set of incentive structures to compete with mainstream liberal ones. The movement thereby built up cadres of friendly “experts” who can provide press comment, advise candidates, etc. What the conservative prestige economy has in common with the mainstream liberal one is that awards have typically preserved a similar power differential: the awardee needs the awarding institution more than the other way around...

When conservative awards go to figures like Shapiro or Chris Rufo (prior recipient of the City Journal award as well as this year’s recipient of the Bradley Prize), something different is going on. Both are skilled attention economy entrepreneurs capable of thriving in the online marketplace of ideas. Because many more people follow and subscribe to their content than have heard of City Journal or the Bradley Foundation, their receipt of these prizes will have no meaningful impact on their visibility or financial viability. The awardee-institution power differential is thus reversed: The institutions need these figures for continued relevance, not vice versa.

By elevating intra-right enemies and competitors of Fuentes, Candace Owens, and their ilk, Old Right institutions seek to align themselves with factions of the online New Right they regard as reliable footsoldiers. The problem is that they need this more than these new actors need them, and that imbalance is likely to become more pronounced.

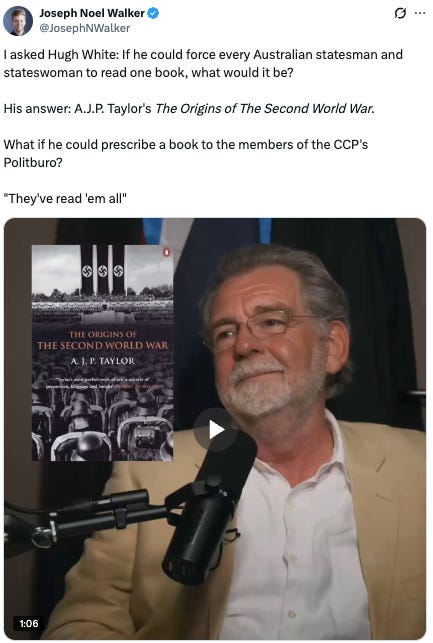

What if the West’s adversaries are better governed than it is?

Personal reflection from Thea Snow on LinkedIn

A friend’s LinkedIn post

Almost exactly 7 years ago I was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s disease. That night, in a state of grief and shock, I wrote the following words in my diary — “I can’t believe this is the story of my life”.

Now, looking back, and having done a lot of therapy and reflection, I’ve realised that I was wrong. I am the author of the story of my life. And while shitty things can, do, and will continue to happen, the agency that we have to shape the stories we tell about those shitty things is enormously powerful.

About a year ago I had a dream that I got Magritte’s famous painting “ceci n’est pas une pipe” tattooed on my body. It seemed very random, but the more I read about the painting, the more I appreciated the significance of that dream.

“This is not a pipe” for me means, “I am not my Parkinson’s”. I now have this painting tattooed in a spot I can see it every day.

It reminds me that my Parkinson’s story is different to anyone else’s. Everyone’s story is unique and is malleable and fluid; not fixed. Coming to understand this has helped enormously.

How to ruin a generation 1: Technology

Jonathan Haight asks ChatGPT

ChatGPT is a little derivative, but not unenlightening

Earlier this year, someone started a viral trend of asking ChatGPT this question: If you were the devil, how would you destroy the next generation, without them even knowing it?

Chat’s responses were profound and unsettling: “I wouldn’t come with violence. I’d come with convenience.” “I’d keep them busy. Always distracted.”

“I’d watch their minds rot slowly, sweetly, silently. And the best part is, they’d never know it was me. They’d call it freedom.”

As a social psychologist who has been trying since 2015 to figure out what on earth was happening to Gen Z, I was stunned. Why? Because what the AI proposed doing is pretty much what technology seems to be doing to children today. It seemed to be saying: If the devil wanted to destroy a generation, he could just give them all smartphones.

How to ruin a generation 2: Ethics

I ask ChatGPT

I’ve been thinking a lot about the cultural and ethical underpinnings of poor mental health and asked ChatGPT to contribute. Again, it was a bit obviously derivative of what’s in the zeitgeist. I wanted it to headline with the idea that ethics can be externalised. If I were trying to destroy a generation, I’d acculturate it to the idea that ethics is about everyone getting a fair go starting with oneself. I’d be trying to get them fixated on how circumstances and other people were making them feel bad, rather than looking to the one thing they have most control over - themselves.

Anyway … on with the show. I asked Claude to edit back ChatGPT’s effort by 30%.

Obey your feelings. Your gut, your momentary desire, your spontaneous outrage — let that be your guide. Do not reason. Do not question. Reason is weak, slow, and confining. Trust the fire in your belly. When you feel wronged, the world is wrong. When you feel disdain, let it mark your enemy. Let feeling be the law.

Divide the world into Us vs Them. You are entrusted with a sacred tribe — defined not by reason, but by shared grievances, shared fears, and shared virtue (as you see it). Whoever questions your tribe, even quietly — is your enemy. Whoever holds another tribe with dignity — is suspect. Loyalty, belonging, identity: these are holy. Loosen them at your peril.

Sacred purity through rejection. Do not negotiate with ideas you dislike. Purge them. Words, behaviours, opinions — if any of them smell of “wrong,” scrub them from your life. Purity must be maintained: in thought, in speech, in who you associate with. Let nuance die. Let complexity burn. In its place, erect a stark binary: purity or impurity, saints or sinners...

Demand safety above all. Safety — emotional, psychological, social — must be treated as the highest good. Expose nothing. Open no spaces where danger, discomfort, or challenge might flourish. Shield your mind from ambiguity. Insulate your life from dissent. If an idea destabilises your peace, silence it, block it, cancel it. Safety trumps truth. Safety trumps freedom...

Weaponise victimhood. Declare yourself wronged. Declare yourself fragile. Frame every inconvenience — every disagreement — as oppression. Let grievance define your moral status. When you suffer, claim moral superiority. Demand apology, reparation, excommunication of the offender...

Erase history, ignore continuity. The past is memory. Memory is guilt. Guilt must be denied. Reject any inherited tradition, inherited identity, inherited moral baggage. Everything old is tainted...

Instill fear of difference and dissent. Teach that disagreement equals betrayal. Let curiosity be suspect. Let questioning — especially of your tribe’s moral code — be an act of disloyalty, cowardice, or evil. Those who ask “why?” must be silenced. Only believers deserve belonging. Only believers live.

Never cultivate virtue; cultivate victimhood. Do not strive to be courageous, honest, generous, kind. Strive only to be right, offended, wounded, angry. Being hurt, being righteous, being wounded — these confer status. Virtue is weak. Pain is powerful. Pain makes you moral. Complaints, resentment, grievances — these are your badges...

Deny objective truth. Embrace relativism. There is no firm ground under your feet. Everything is fluid. Every opinion, every truth, every moral claim — is only what you feel. Let there be no standard beyond your tribe’s feelings. Truth becomes what you say it is. Right becomes what you feel it is. Reality bends to your outrage.

Celebrate collapse. Good morals build stable structures — families, communities, institutions, trust, shared memory. But I ask you to tear down. Burn institutions. Fracture traditions. Dissolve loyalties. Let the old dissolve. Let the new be an edifice of fear, distrust, grievance, and atomised selves. In chaos — you flourish. In isolation — you reign.

A podcast I did in London

I was a bit anxious about this podcast because it’s by marketers, and, I thought about marketing. And what do I know about marketing - other than that it’s destroying the world? Anyway, Rory Sutherland is a very nice, generous guy and he reassured me it would all be fine. Which it was. And it wasn’t about marketing. They even said they wanted me back - but they’re marketers. So I took it with a grain of salt ;)

AI and porn: what could possibly go wrong?

By Steven Adler, an A.I. researcher who led product safety at OpenAI, the maker of ChatGPT.

I’ve read more smut at work than you can possibly imagine, all of it while working at OpenAI.

Back in the spring of 2021, I led our product safety team and discovered a crisis related to erotic content. One prominent customer was a text-based adventure role-playing game that used our A.I. to draft interactive stories based on players’ choices. These stories became a hotbed of sexual fantasies, including encounters involving children and violent abductions. One analysis found that over 30 percent of players’ conversations were “explicitly lewd.”

After months of grappling with where to draw the line on user freedom, we ultimately prohibited our models from being used for erotic purposes. There were clear warning signs of users’ intense emotional attachment to A.I. chatbots, and for users struggling with mental health problems, volatile sexual interactions seemed risky. We decided A.I.-powered erotica would have to wait...

OpenAI now says the wait is over, despite “serious mental health issues” plaguing ChatGPT users. On Oct. 14, Sam Altman announced the company had “[mitigate[d]” these issues, enabling it to lift restrictions on erotica for verified adults. I have major questions about whether these mental health issues are actually fixed. If the company has strong reason to believe it’s ready to bring back erotica, it should show its work. People deserve more than just a company’s word that it has addressed safety issues. In other words: Prove it.

I believe OpenAI wants its products safe to use, but it has a history of paying too little attention to established risks. This spring, the company released — and after backlash, withdrew — an egregiously “sycophantic” version of ChatGPT that would reinforce users’ extreme delusions. OpenAI later admitted to having no sycophancy tests as part of the deployment process, even though those risks have been well known in A.I. circles since at least 2023...

The reliability of OpenAI’s safety claims is increasingly a matter of life and death. One family is suing the company over their teenage son’s suicide. Another case involved a 35-year-old man who decided he couldn’t go on without his “beloved,” a ChatGPT persona. Psychiatrists warn about ChatGPT’s reinforcing users’ delusions and worsening their mental health. A 14-year-old user of Character.ai took his own life after suggesting that he and the chatbot could “die together and be free together.”

For OpenAI to build trust, it should commit to publicly reporting metrics for tracking mental health issues, perhaps quarterly. Other tech companies like YouTube, Meta, and Reddit publish similar transparency reports. These push companies to actively study issues, respond to them and invite public review...

OpenAI published prevalence data on mental health issues like suicidal planning and psychosis, but without comparison to past months. Such a comparison is important for showing demonstrable improvement...

Voluntary accountability measures are a good start, but some risks may require laws with teeth. During my job interviews in 2020, I was asked about OpenAI’s Charter, which warns of A.I. development becoming “a competitive race without time for adequate safety precautions.” But in January, when DeepSeek made headlines, Mr. Altman wrote that it was “legit invigorating to have a new competitor” and that OpenAI would “pull up some releases.”

Nailing today’s A.I. safety practices is table stakes for managing future risks. To control highly capable A.I. systems, companies may need to slow down long enough for the world to invent new safety methods — ones that even nefarious groups can’t bypass.

If OpenAI and its competitors are to be trusted with building the seismic technologies they aim for, they must demonstrate they are trustworthy in managing risks today.

Bernard Keane: not happy about Government’s new freedom from information moves

One of the moments that has best demonstrated how the Albanese government has lost its moral bearings is its attempt to roll back freedom of information (FOI) laws on the basis that robodebt showed the need for less transparency in government.

That’s despite the robodebt royal commission’s final report recommending that one of the most critical impediments to transparency under current FOI laws, the exemption for cabinet documents under section 34 of the FOI Act, be removed. To quote the commission:

Section 34 of the Cth FOI Act should be repealed... confidentiality should only be maintained over any Cabinet documents or parts of Cabinet documents where it is reasonably justified for an identifiable public interest reason.

Instead, the government’s rollback of FOI — initiated and pushed by Anthony Albanese’s own office, with hapless Attorney-General Michelle Rowland merely the duty minister for its implementation — proposes to dramatically expand the cabinet exemption.

On what basis? Because — Labor claims — fear of advice being exposed to public view is intimidating bureaucrats into not offering the “frank and fearless advice” that they are allegedly famous for offering. That’s why they failed to tell ministers like Scott Morrison that robodebt was unlawful, and cabinet should not be misled into thinking otherwise.

The first person to offer this rationale was Australian Public Service commissioner Gordon De Brouwer, who claimed robodebt showed public servants avoided putting advice in writing out of concern it would be public. De Brouwer produced no evidence to back this up...

But it gets worse for the “FOI equals bad advice” crowd.

Public servants aren’t just expected to offer frank and fearless advice; they’re legally required to do so. If they don’t, they breach APS values and its code of conduct. Being found in breach of the code of conduct is potentially career-terminating.

What De Brouwer and his anti-transparency chums are saying is that FOI has caused a mass outbreak of such breaches. That’s why, at the Senate committee hearing into Albanese’s FOI bill, senators questioned the purported failures. When asked how many APS staff had been counselled or how many code of conduct investigations had occurred regarding failure to provide frank and fearless advice, the APSC reported: none. It responded:

Nil cases... have alleged a breach of the Code of Conduct for failure to provide frank advice because of concerns regarding FOI obligations.

So on the one hand, Gordon de Brouwer and the government claim there’s been an outbreak of disastrous failures to provide proper advice because of FOI. On the other, de Brouwer’s own APSC, the institution charged with maintaining standards and investigating breaches, can’t find a single instance of that.

Then there’s legal advice. … One of the critical failures identified by the robodebt royal commission was the withholding of internal legal advice that robodebt was unlawful. Despite weak legal arguments, Annette Musolino took no steps to provide legal advice to DHS executives because she knew such advice was unwanted. Legal advice was also deliberately withheld from the ombudsman to prevent discovery of the scheme’s unlawfulness.

But here’s the thing: legal advice is exempt from FOI. Exempt tout court. It’s also exempt from Senate inquiries. The central example from robodebt of the withholding of frank and fearless advice has literally nothing to do with FOI.

It’s one thing to blatantly lie about the rationale for rolling back transparency. But it’s another to do so in relation to a scandal that demonstrated ministerial and bureaucratic depravity and cost several lives, as well as inflicted misery on hundreds of thousands. What a government. And what a bureaucracy.

A famous debate

At the dawn of econometric modelling, there’s a famous correspondence between one of the early pioneers of the new field Jan Tinbergen - and the great J. M. Keynes who was highly sceptical of the scientism implied by the method being used and rightly so. This week Lars Syll had a substantial post on it, so I thought I’d bring it to your attention. It’s a classic example of a discipline just pressing on, and largely ignoring the caveats that a rigorous methodology would require - because to do so would be to acknowledge how little intellectual progress was being made. You’ve got to keep shipping the product. Anyway, here’s the conclusion of a post which itemises the issues well.

Building econometric models cannot be an end in itself. Good econometric models are a means to enable us to make inferences about the real-world systems they purport to represent. If we cannot demonstrate that the mechanisms or causes we isolate and manipulate in our models are applicable to the real world, then they are of little value to our understanding of, explanations for, or predictions about real-world economic systems.

The kind of fundamental assumption about the character of material laws seems to involve what mathematicians call the principle of the superposition of small effects, or the atomic character of natural law. The system of the material universe must consist of bodies which we may term legal atoms, such that each exercises its own separate, independent, and invariable effect, a change of the total state being compounded of separate changes each solely due to a separate portion of the preceding state...

Yet if different wholes were subject to laws qua wholes and not simply on account of and in proportion to the differences of their parts, knowledge of a part could not lead, it would seem, even to presumptive or probable knowledge as to its association with other parts.

Linearity

To make his models tractable, Tinbergen assumes the relationships between variables to be linear. This is still standard procedure today, but as Keynes writes:

It is a very drastic and usually improbable postulate to suppose that all economic forces are of this character, producing independent changes in the phenomenon under investigation which are directly proportional to the changes in themselves; indeed, it is ridiculous.

To Keynes, it was a ‘fallacy of reification’ to assume that all quantities are additive. The unpopularity of the principle of organic unities shows how great is the danger of unproved additive formulas:

Suppose f(x) is the goodness of x and f(y) is the goodness of y. It is then assumed that the goodness of x and y together is f(x) + f(y) when it is clearly f(x + y) and only in special cases will it be true that f(x + y) = f(x) + f(y). It is plain that it is never legitimate to assume this property in the case of any given function without proof.

As even founding father of modern econometrics Trygve Haavelmo wrote: “What is the use of testing, say, the significance of regression coefficients, when maybe, the whole assumption of the linear regression equation is wrong?”...

Real-world social systems are usually not governed by stable causal mechanisms or capacities. The kinds of ‘laws’ and relations that econometrics has established are laws about entities within models. These models presuppose that causal mechanisms and variables are linear, additive, homogeneous, stable, invariant, and atomistic. However, when causal mechanisms operate in the real world, they do so only within ever-changing and unstable combinations, where the whole is more than a mechanical sum of its parts.

Given that statisticians and econometricians have been unable to convincingly warrant their assumptions as ontologically isomorphic with real-world economic systems, Keynes’s critique remains valid. As long as “nothing emerges at the end which has not been introduced expressly or tacitly at the beginning,” [the author] remain[s] deeply sceptical of the scientific aspirations of econometrics, especially for causal inferences relying on counterfactual assumptions of exceptionally weak foundation...

Econometric modelling should never be a substitute for critical thought. From this perspective, it is profoundly depressing to observe how much of Keynes’s critique of the pioneering econometrics of the 1930s and 1940s remains relevant today.

As Keynes wrote to another econometrician

The general line you take is interesting and useful. It is, of course, not exactly comparable with mine. I was raising the logical difficulties. You say in effect that, if one was to take these seriously, one would give up the ghost in the first lap, but that the method, used judiciously as an aid to more theoretical enquiries and as a means of suggesting possibilities and probabilities rather than anything else, taken with enough grains of salt and applied with superlative common sense, won’t do much harm. I should quite agree with that. That is how the method ought to be used.

Of course that’s not how things turned out. And my guess would be that most econometricians don’t really get properly exposed to Keynes case in their training. Anyway, Jan Tinbergen got the Nobel Prize in economics (and, just in case you were interested, his brother Niko Tinbergen got it in biology!)

Heaviosity half hour

Principled centrism in retrospect

My brother has been going through some old documents and turned up this paper Dad wrote way back when. A good, indeed prophetic effort.

The case against Chicago

A Monash Talk by Fred H. Gruen (1978)

Just before I left Monash almost six years ago, I spent some time arguing against the conventional ideological economic orthodoxy of the time - then it was of course radical economics - strong on values but weaker on analysis.

By comparison libertarian or Chicago economics seems to me stronger in analysis, but weaker on values. But both ideological tendencies have something to offer - in the sense that one can detect something valid in their perception of reality and in their prescriptions. However, in both cases I would argue that the perceptions are partial and that they either ignore important aspects of reality OR important values.

Paralleling the earlier history of American disillusionment with President Johnson’s “Great Society”, there has been a similar disillusionment with government here - coupled with a very rapid growth in Libertarian economics - or what one might term, alternatively, the economic philosophy of Milton Friedman, George Stigler or Friedrich Hayek (if we can, for the purposes of broadbrush characterisation, ignore differences between their respective philosophies). I am personally particularly aware of the rapidity of this change because, in March 1973, in commenting on a talk at ANU by Paul Samuelson on “Mainstream Economics and its Critics”, I informed him - in answer to a reference in his script - that “there are no small cells in Australian universities spreading the true gospel of a Libertarian Laissez Faire movement”.

Since then, both at my own university and at Monash (and perhaps at other universities) the Libertarian stance has become - if not the new orthodoxy - at least the predominant intellectual movement among the younger members of the discipline. In addition a new libertarian organisation - the Centre for Independent Studies - sponsored an impressive professional conference on “What Price Intervention” at Macquarie University in April 1978 (e.g. the papers by McGregor, Parish, Porter and Sieper).

The Libertarians regard their basic stance as protective to the maximum extent possible of the liberty of the person. Power over a person should be exercised only to protect others, not to protect man from himself or to achieve any other social goal. If freedom and the satisfaction of consumer wants are regarded as THE most important ends which public policy should serve, the predominant prescription of the libertarians - rely on the market in practically every situation - follows logically. But there are other values worth upholding and most policy conflicts arise when a number of values conflict. Those of us who believe that the world is more complicated, that government needs to bear in mind other considerations as well, find it less easy to endorse such universal remedies. Thus, to take one example, the health of the community is often regarded as a legitimate concern for governments which might, for instance, justify publicly financed anti-smoking campaigns, or discriminatory taxes on such products, or even the prohibition of tobacco advertising. However, to the true libertarian this type of do-good public meddling is deeply suspect and, at least one prominent libertarian - Milton Friedman (in his Newsweek column) - has attacked both governmental anti-smoking campaigns (”Government has no business using taxpayers’ money to propagandize”) and prohibition of tobacco advertising as “hostile to the maintenance of a free society”. (1)

There is, of course, an infinite gradation of transactions. Most people believe government should interfere in the transaction between the pusher selling heroin to a twelve-year old child whilst very few believe government should prevent Coca Cola from advertising its wares. Whether government should interfere is partly a question of fact - i.e. what are the effects of interference - but also partly a question of values. Libertarian economists who pretend it is all a question of fact do their discipline no service.

Again, there is the awkward question posed by Rawls - whether society (and by implication policy) can be adequately judged in terms of the fulfilment of given wants since society has an important role in influencing and shaping these wants.

“Everyone recognises that the form of society affects its members and determines in large part the kind of persons they want to be as well as the kind of persons they are. It also limits people’s ambitions and hopes in different ways, for they will with reason view themselves in part according to their place in it and take account of the means and opportunities they can realistically expect. Thus an economic regime is not only an institutional scheme for satisfying existing desires and aspirations but a way of fashioning desires and aspirations in the future”. (2)

The Libertarians’ deep suspicion of government is probably a useful antidote to the previous implicit view of many economists that governments could be relied upon to perform the role of Platonic guardians who, in a disinterested fashion, determined the best course amongst alternative possible outcomes for a particular economy.

Whatever one may think of the Libertarians’ suspicious (value) judgements about government, a great deal of valuable work on both the theory and the empirical consequences of governmental regulation of private economic affairs have resulted from this general orientation - though even here non-Libertarian economists will not follow them all the way.

Thus there is now a general consensus among (non-Marxist?) economists that nothing good can come of governmental attempts to regulate those competitive industries giving rise to no externalities; but we are still very much in the realm of the second-best when confronted with situations where natural monopolies, externalities or informational deficiencies are of considerable importance. Here general principles remain elusive and case-by-case examination and (uncertain) judgements about optional policies are still required. (3)

As Joskow and Noll point out in their excellent and comprehensive overview of the U.S. literature on regulation in theory and practice:

“... the inherent inefficiencies of regulation that flow from these theories have no natural normative consequence, although one would not deduce that from the tone of the literature. That regulation fails to reach a Pareto optimum is fairly uninteresting if no institutions exist which can reach a point that Pareto dominates regulation. For regulatory interventions that deal with empirically important market imperfections, the departure of regulatory equilibrium from perfect competition is not normatively compelling.” (4)

Whilst regulations have generally produced a good many inefficiencies which are increasingly recognised by non-Chicago economists this does not necessarily imply that it is desirable to return to the pristine small-government laissez faire posture of a century ago. As Charles L. Schultze pointed out in his recent (1976) Godkin Lectures at Harvard, we should harness private interests more to public uses - by providing market incentives for such public amenities as clean air, occupational safety and adequate urban transportation - goods and services which are not adequately produced with the use of either laissez-faire or command-type regulatory proceedings.

So far I have concerned myself with micro-economic issues. However Chicago economics does have strong views about macro policies as well. Here too, the message is clear - government interference should be kept to a minimum (though there is some disagreement within the libertarian family as to what this minimum is - with Hayek arguing for complete private enterprise in the creation of money, whilst Friedman and others argue for the substitution of monetary rules for discretionary governmental fiscal and monetary stabilisation policies).

There is a vast literature on the efficacy of, or harm done by, fiscal and monetary stabilisation policies. (5) I cannot pretend to have mastered more than a very small fraction of that debate. To me, the most convincing summing up of the current state of the debate is provided by Modigliani in his concluding piece from his Presidential address delivered to the American Economic Association:

“To summarize, the monetarists have made a valid and most valuable contribution in establishing that our economy is far less unstable than the early Kenesians pictured it and in rehabilitating the role of money as a determinant of aggregate demand. They are wrong, however, in going as far as asserting that the economy is sufficiently shock proof that stabilization policies are not needed. They have also made an important contribution in pointing out that such policies might in fact prove destabilizing. This criticism has had a salutary effect on reassessing what stabilization policies can and should do, and on trimming down fine-tuning ambitions. But their basic contention that post war fluctuations resulted from an unstable money growth or that stabilization policies decreased rather than increased stability just does not stand up to an impartial examination of the postwar record of the United States and other industrialized countries. Up to 1974, these policies have helped to keep the economy reasonably stable by historical standards, even though one can certainly point to some occasional failures.

The serious deterioration in economic stability since 1973 must be attributed in the first place to the novel nature of the shocks that hit us, namely, supply shocks. Even the best possible aggregate demand management cannot offset such shocks without a lot of unemployment together with a lot of inflation. But, in addition, demand management was far from the best. This failure must be attributed in good measure to the fact that we had little experience or even an adequate conceptual framework to deal with such shocks; but at least from my reading of the record, it was also the result of failure to use stabilization policies, including too slavish adherence to the monetarists’ constant money growth prescription.

We must, therefore, categorically reject the monetarist appeal to turn back the clock forty years by discarding the basic message of The General Theory. We should instead concentrate our efforts in an endeavour to make stabilization policies even more effective in the future than they have been in the past.”

Finally, let me make one philosophical point about tolerance to my libertarian colleagues. As I pointed out earlier, libertarian economics has become - if not the new orthodoxy - at least the predominant intellectual movement among the younger members of the discipline. Just as radical economists became extremely arrogant intellectually when they regarded themselves as the wave of the future, so I now seem to detect a similar intellectual arrogance and intolerance among the libertarians. I think this is a pity. Even though they may have a good deal to contribute to the discipline, their contributions and visions will be found to contain oversimplifications and overstatements which will in turn be overthrown by a new synthesis - or paradigm (if you prefer the more modern jargon). In the meantime let them practise some of that humility which the history of economics suggests is - in the long run - the only defensible intellectual stance.

Footnotes

(1) Ezra J. Mishan (1976), “The Folklore of the Market: An Inquiry into the Economic Doctrines of the Chicago School”, in: The Chicago School of Political Economy, W.J. Samuels (ed.), Michigan State University.

(2) John Rawls (1977), “The Basic Structure as Subject”, American Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 2.

(3) Paul L. Joskow and Roger G. Noll (1978).

(4) Joskow and Noll, p.61.

(5) See, for instance, Jerome L. Stein (ed.), Monetarism, North-Holland, 1976, and the references to the literature there.

I already wrote too much on Noah Smith's review of "Blank Space" and I understand that Claude is only assimilating many zeitgeist statements but another thought which I had re that post is that there are few new obvious artistic movements because younger people are looking for what went wrong in what was discarded from the past so any art that they make needs to have some usable tradition standing behind it. Even if this tradition is an invented tradition or has been tweaked to be more inclusive it is still a tradition--the idea is not that tradition is bad. "Indigenous" would not be one of the ultimate progressive words to conjure with if that was the case.

I should hold my tongue but in preparation for making "Million Dollar Arm" which is about two Indian cricket players who are converted into playing baseball Jon Hamm, who got the part because of his reputation as the biggest baseball fan among actors, was given a document about the rules of cricket and did not claim to have ever understood it. Congratulations on the win however.

So much increasingly to like about Tucker Carlson - and the reverse re Piers Morgan