Complexity, clichés and bullshit

I recently on a podcast called Simplifying Complexity. In a previous interview on the same podcast I was somewhat critical of those who peddle ‘complexity’ as a new paradigm in economics. While some of the formal techniques of modelling complexity can be useful, I don’t think they offer a new paradigm. Until someone can show something better, the old paradigm of J.R. Hicks is the best we can do.

Formalise where it helps you see further;

Have a clear (Socratic/Confucian) idea of the limits of how much this helps; and

Beyond that point, do the best you can with ad hoc models and informal reasoning.

As the great economist John Hicks - he who cooked up the IS-LM curve puts it:

The more characteristic problems are problems of change, of growth and regression and of fluctuation. The extent to which these can be reduced into scientific terms [Hicks’ other writing suggests he means via formal economic theory] is rather limited; for at every stage in an economic process new things are happening, things which have not happened before - at the most they are rather like what has happened before. . . . As economics pushes on beyond 'statics' it becomes less like science and more like history.

Be that as it may, at least there is some formal rigour to claims about complexity science in economics. That is not the case when we hear clichés about ‘complexity’ in business strategy and in the delivery of social services. Here the cliché of 'complexity' as some new lens really runs rampant. The idea is constantly peddled that the current system is blinkered in its thinking. The word 'linear' will be thrown around. And what’s needed is a more holistic ‘systems lens’ and a view from ‘complexity science’ or some such.

However, to me, to the extent that this is coherent at all, this misdiagnoses the problem. The reason existing systems are so often dysfunctional is that they're not, ultimately built to work for users. They're built to address the needs of those building the system. Building them so they do work takes more than some consultants coming in with a new 'holistic' view of the problem. And if the consultants do have insights into the problem and how to fix it, how will they get it to stick once they’ve toddled off to their next gig leaving their handiwork to all the forces that produced the initial dysfunction?

Anyway, Rory Sutherland, a very intelligent and generous man whom I am proud to call a friend often uses the kind of terminology I’m critiquing. In his case I think the clichés sell his own thinking short. He’s not, IMO a ‘complexity’ thinker, but someone who pokes around and notices things that are subtly, but profoundly misdescribed in the current discourse and speaks to correct that. That’s how I’d describe my own method too.

So I suggested an exchange — me versus Rory — to the host of ‘Simplifying Complexity’ and we all enjoyed ourselves, disagreed, agreed and perhaps made a little progress.

See what you think either on the gizmo below or on my podcast channel here.

Extinction: That giant sucking sound coming from your phone

On allowing us to survive the various extinctions picking up speed around us. On the other hand, we can’t do it on our own. Us humangoes only get anywhere entangled in the webs of mutual obligation provided by (formal and informal) institutions. The author doesn’t say how we can evolve them in defence of our humanity?

The extracts below are mainly a teaser.

Every great technological change has a destructive shadow, whose depths swallow ways of life the new order renders obsolete. But the age of digital revolution — the time of the internet and the smartphone and the incipient era of artificial intelligence — threatens an especially comprehensive cull. It's forcing the human race into what evolutionary biologists call a "bottleneck" — a period of rapid pressure that threatens cultures, customs and peoples with extinction.

When college students struggle to read passages longer than a phone-size paragraph and Hollywood struggles to compete with YouTube and TikTok, that's the bottleneck putting the squeeze on traditional artistic forms like novels and movies.

When daily newspapers and mainline Protestant denominations and Elks Lodges fade into irrelevance, when sit-down restaurants and shopping malls and colleges begin to trace the same descending arc, that's the bottleneck tightening around the old forms of suburban middle-class existence.

When moderates and centrists look around and wonder why the world isn't going their way, why the future seems to belong to weird bespoke radicalisms, to Luigi Mangione admirers and World War II revisionists, that's the bottleneck crushing the old forms of consensus politics, the low-key ways of relating to political debates...

When young people don't date or marry or start families, that's the bottleneck coming for the most basic human institutions of all.

And when, because people don't pair off and reproduce, nations age and diminish and die away, when depopulation sweeps East Asia and Latin America and Europe, as it will — that's the last squeeze, the tightest part of the bottleneck, the literal die-off.

The idea that the internet carries a scythe is familiar — think of Blockbuster Video, the pay phone and other early victims of the digital transition. But the scale of the potential extinction still isn't adequately appreciated.

This isn't just a normal churn where travel agencies go out of business or Netflix replaces the VCR. Everything that we take for granted is entering into the bottleneck. And for anything that you care about — from your nation to your worldview to your favorite art form to your family — the key challenge of the 21st century is making sure that it's still there on the other side...

That challenge is made more complex by the fact that much of this extinction will seem voluntary. In a normal evolutionary bottleneck, the goal is surviving some immediate physical threat — a plague or famine, an earthquake, flood or meteor strike. The bottleneck of the digital age is different: The new era is killing us softly, by drawing people out of the real and into the virtual, distracting us from the activities that sustain ordinary life, and finally making existence at a human scale seem obsolete.

In this environment, survival will depend on intentionality and intensity. Any aspect of human culture that people assume gets transmitted automatically, without too much conscious deliberation, is what online slang calls NGMI — not going to make it.

Languages will disappear, churches will perish, political ideas will evanesce, art forms will vanish, the capacity to read and write and figure mathematically will wither, and the reproduction of the species will fail — except among people who are deliberate and self-conscious and a little bit fanatical about ensuring that the things they love are carried forward...

It starts with substitution: The digital age takes embodied things and offers virtual substitutes, moving entire realms of human interaction and engagement from the physical marketplace to the computer screen. For romance, dating apps supplant bars and workplaces and churches. For friendship, texting and DMing replaces hanging out. For entertainment, the small screen replaces moviegoing and live performance. For shopping and selling, the online store supplants the mall. For reading and writing, the short paragraph and the quick reply replace the book, the essay, the letter...

Have the child. Practice the religion. Found the school. Support the local theater, the museum, the opera or concert hall, even if you can see it all on YouTube. Pick up the paintbrush, the ball, the instrument. Learn the language — even if there's an app for it. Learn to drive, even if you think soon Waymo or Tesla will drive for you. Put up headstones, don't just burn your dead. Sit with the child, open the book, and read.

As the bottleneck tightens, all survival will depend on heeding once again the ancient admonition: I have set before you life and death, blessing and curse. Therefore choose life, that you and your offspring may live.

Brad and Noah are back

Brad Delong and Noah Smith’s podcast is back after a year’s hiatus. With a year’s having gone by to catch up on, I found this particularly good, though it’s a bit slow for the first ten or fifteen minutes. It led me to Noah’s 2013 article on redistributing respect I reproduce immediately below.

Redistribute wealth? No, redistribute respect

Noah Smith from 2013.

"It is said that heaven does not create one person above or below another person."

Yukichi Fukuzawa

… I've come to realize that there is another important dimension of equality that I care about. Maybe more than any of the others. It's equality of respect. I had this realization (as with so many others) while living in Japan. I first noticed it when I was sitting in a "kaiten-zushi" restaurant, watching some cooks chop fish. It was robotic, repetitive work, about as difficult - and about as well-paid - as flipping burgers. But my Japanese friend referred to one of those cooks as "sushi-ya-san", meaning "Mr. Sushi Chef". She used the honorific reflexively, not patronizingly or sarcastically. The respect for this low-paid, low-skilled worker was reflexive, automatic. I suddenly wondered if we could get Americans to start calling burger-flippers "sir". The thought made me laugh...

There are other ways in which the customs of Japanese society work to encourage equal respect. Japan is not a particularly "equal" country in terms of income; its Gini coefficient is higher than that of most European countries'. But conspicuous displays of wealth are rare. Rich people live in secluded apartments and houses concealed by high stone walls, instead of in the palatial mansions preferred by wealthy Americans. No one discusses how much money anyone makes...

I feel like the America I grew up in could learn a thing or two from Japan in this regard. I don't know if the word "loser" was a common insult before the 1980s, but in recent decades it has become ubiquitous. People who work in the service industry almost always seem ashamed when they tell me what they do for a living. Low-skilled workers are treated in a peremptory way, constantly reminded that they are "losers". Americans wear T-shirts that say "Second place is the first loser", and "Winning isn't everything; it's the only thing."

I have the vague sense that things used to be different in America. We've never called fry cooks "-san", but (as someone pointed out to me on Twitter the other day) we have an even more egalitarian tradition: calling everyone by their first names. The American style of respect is to treat everyone like "one of the guys" (including women), no matter how rich or poor they are. In the 1920 novel Main Street, which I read recently, this attitude of deliberate informal egalitarianism is referred to as "democracy"...

Today when we think of "democracy", we think of formal institutions like elections, constitutions, and rights under the law. But it seems that our forebears also conceived of "democracy" as an attitude of equal respect for all people regardless of social station. Equal respect could thus be seen as one of America's "founding virtues". And it's not hard to imagine that when the writers of the Declaration of Independence wrote that "all men are created equal" - that cryptic, endlessly-debated phrase - what they meant was not equality of ability, but as deserving of equal respect by society.

I have little hard evidence that America has taken a turn away from this founding virtue. But I definitely have that feeling...

But I think American liberals have also made the mistake of focusing too much on income and wealth as the measures of success. Every chart and graph we see about America's increase in "inequality" is about either money, or the likelihood of getting money. Sure, disparities of wealth are distasteful. Sure, money is one thing that confers social status. But by focusing on it obsessively, I think liberals are helping to cement its paramount importance as the end-all and be-all of social outcomes.

This is bad because it cements an American attitude of crass materialism, but it's also bad because it ignores achievable types of social equality while questing after the unattainable. Societies can be more or less equal in terms of wealth and income, but only to a degree; as Vilfredo Pareto observed, and as studies have later confirmed, every society on Earth has wealth and income distributions that follow some kind of power law, where a small fraction earn and command much more money than the vast majority. You can make the [curve] flatter, but never close to flat.

Whether we're questing after a narrow money-based vision of equality or callously celebrating the "competitiveness" created by material inequality, we Americans seem to have mostly forgotten about equality of respect. This is bad not just because I personally dislike it, but because in a developed country like ours, respect is a big part of what makes people happy. In fact, I suspect that our turn away from egalitarianism is one factor behind our bifurcation into a class society.

I want this to change. I want to move back toward a society where the hard work of an unskilled laborer is considered worthwhile in social interactions, regardless of how many dollars it brings home. I want to move back toward a society where being a good parent or a friendly neighbor earns as much respect as making a hundred million dollars on Wall Street.

In other words, I want our "democracy" back. We need to redistribute respect.

And a later post arguing that woke was an attempt to redistribute respect.

I think wokeness is in part an attempt to renegotiate the distribution of respect in American society. So many of the things we associate with wokeness — pronoun culture, “canceling” writers who appear to traffic in stereotypes, re-centering American history around Black people, the whole idea of “centering the voices of marginalized groups”, and so on — are explicitly about respect. Wokeness does include social movements with real material aims (e.g. defunding the police), but mostly it’s a cultural movement whose goal is to change the way Americans talk and think about each other.

Reading by Candlelight and Coal Dust

Before the Spreadsheets: An Intellectual Life Worth Reclaiming

A review of a book on the amazing story of the British working class’s commitment to self-betterment including by reading and studying the classics of literature and science. Nevertheless, like Ross Douthat’s column above, it has a pretty tame and conservative outlook on the lessons of history for the future.

I am not a fan of separating classes of society. In fact, I cringe at the very mention of classes and caste systems, however real (or imagined) they may be. Nevertheless, I greatly admire the work of Jonathan Rose detailing the British working class, the bottom of the economic pyramid, in his masterwork The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, now in its third publication.

The period of analysis in Rose's book spans roughly from the late 18th century through the mid-20th century, with a strong concentration on the 19th century and early 20th century, particularly the Victorian and Edwardian eras. He uses memoirs, oral histories, library records, and educational archives to reconstruct the reading and intellectual practices of British workers during this transformative period in industrial and political life...

This is not a story of hardship ennobled by culture. It is a record of an insurgency fought in secondhand bookshops, between shifts at the mill, and by candlelight in rented rooms. Jonathan Rose demolishes the pretensions of both the genteel historian and the radical theorist, not by rhetorical flourish, but by forensic resurrection. He shows that the working poor of Britain were once the most serious readers in the empire, consumers and critics of canonical literature who saw in Shakespeare not a curriculum but a comrade.

Rose does not begin with a thesis. He begins with the lives that historians had neither the time nor the imagination to record: a miner who reads Plato underground, a servant girl found with a volume of Shelley in her apron pocket, a baker's son quoting Ruskin to an indifferent magistrate. These were not exceptions. They were, for a time, the rule...

Reading was a lifeline, a solace, and an assertion.

"I read," said one ironworker, "because I wanted to say what I thought, not what I was told."

The paradox Rose exposes is uncomfortable for modern sensibilities: that the working class once read more seriously, more adventurously, and more democratically than today's university-credentialed elite. The autodidacts of the Victorian and Edwardian years were not guided by syllabi or triggered by texts. They read for transformation. They read to join a conversation they had been told was not theirs...

Lifelong Learning Rose's polemic is not just scholarly; it is epic. A teenage weaver, hungry for more than bread, pores over Darwin's Descent of Man by the glow of a gas lamp. A Black Country nailmaker teaches himself Latin to read Virgil in the original. In an Irish tenement, a bricklayer's daughter annotates Middlemarch in the margins of a borrowed Everyman's edition...

This diversity is central. As Rose demonstrates, the intellectual life of the British working class was not monolithic. Its texture varied by trade and by town: Scottish foundry workers favored science and theology; Welsh colliers devoured poetry; Yorkshire textile workers wrote memoirs in margins and margins of factory calendars.

Crucially, the canon these readers pursued was often conservative. "Sir John Lubbock's Hundred Best Books", was embraced as a radical act of self-cultivation. Why? Because these texts, however traditional, represented access. To read Milton or Johnson or Carlyle was not to bow before aristocratic tastes but to claim parity.

"What they read," Rose notes, "were books that conferred dignity and demanded discipline."

The authority of the canon was, in this context, a ladder up, not a leash tying them down...

An Elegy But for all its celebration of working-class literary hunger, Rose is also writing an elegy. The third edition of the book opens with a prelude of quiet fury: the gains of two centuries are in retreat. We are, Rose suggests, witnessing a cultural counter-revolution. The liberal arts, once a ladder to dignity and dissent, are being replaced by credentialism, surveillance pedagogy, and a marketplace that appraises curiosity as wasteful unless it turns a profit.

The stakes, Rose argues, are not merely cultural. They are democratic. When literature is fenced off by gatekeepers, when the idea of truth becomes a matter of credential rather than contestation, we don't just lose readers. We lose citizens.

"The classics," he writes, "equipped the governing classes to rule. Then the politics of equality must begin by redistributing this knowledge to the governed classes."

This is not a quaint appeal to read more. It is a demand to reclaim the intellectual commons...

Reclaiming the Future We live in a moment when the humanities must justify themselves in spreadsheets. It is hard not to suspect that this is precisely because they remain one of the last arenas where dangerous questions might still be asked. In that sense, Rose's book is both requiem and recruitment. It mourns the disappearance of a reading culture forged in hardship, but it also calls upon us, with rare moral clarity, to rebuild it...

The book is highly recommended, it is littered with positive stories of people who had no formal education and through "mutual improvement provided invaluable training in forming and expressing opinions." But overall it shows us that Robert Darnton was right to treat print and reading, rather than economics, as the prime cause of the French Revolution.

Could a societal return to wide reading spark the critical thinking necessary to build a better future, just as it fueled the aspirations of those emerging from the mines, workshops, and factories of the early twentieth century?

“I have not been so thrilled in years”

One writer’s response to AI

The author of this piece - Chor Pharn - fed his past corpus into ChatGPT 4o and asked for advice on, first, whether he was repeating himself, and further what he should try to write next. It’s quite a piece. ChatGPT’s last bit of advice was this.

Open your next essay with this:

The age of civilisation-states gave us one clarity: the monk builds, the missionary fragments, and the engineer-king installs.

But that age is ending too. The machine is now running — whether or not we believe in it.

So what comes after? A world run on fumes? Or something else?

Then take us somewhere unexpected.

Want help writing that next piece? We can start sketching now.”

To which I joked to 4o,

“You do know I write at Benjamin Bratton’s Antikythera program on planetary infrastructure right? It is all about the machine civilisation.”

And we went on and on.

I felt I was playing with different, and better, cognitive versions of myself and I have not been so thrilled in years. I feel more dispersed but also integrated, and am trying to find a visual or a heuristic to better describe what that means.

Give 4o a try.

Huxley on technology

This is a fun interview to listen to, but I was struck by Huxley’s observation that even where there’s “a considerable constitutional tradition which puts a brake on” invidious uses of technology reminding us that the technology is supposed to be our servant not our master. Nevertheless as he admits, “In the long run, we generally succumb”. I think the same can be said of the social, economic and political technologies of markets of electoral competition and of bureaucracy. They set up certain gradients, systematically rewarding what works to the advantage of the powerful and over time, however odious it might have been regarded in the host culture, and by earlier generations, the constraints they impose on behaviours gradually recede.

Like Marx said “all that is solid melts into air”.

Ruxandra weighs in on Curtis Yarvin

“If Americans want to change their government, they’re going to have to get over their dictator phobia,”

Curtis Yarvin

You needn’t interest yourself in the specific defence of Scott Alexander which is the ostensible subject of this post to be interested in my extract from it below. (And the extract above for that matter!)

The average reader of The New York Times must have been a bit puzzled as to why the magazine chose to interview a 51 year old guy called Curtis Yarvin for its 18 January 2025 issue: to most, he must have looked as coming out of nowhere, an obscure intellectual. To those “online” enough, he is anything but. Curtis, also known as Mencius Moldbug, has long been at the heart of the so-called “Dark Enlightenment”, an ideology that I have witnessed growing in influence in the last years of being “online”, only for this to culminate in what one could consider real political influence. Don’t take it from me, a very online person, who might be biased to assign too much importance to internet writers; take it from an article in another mainstream outlet, Time Magazine. The following excerpt not only highlights Yarvin’s growing influence, but also sketches, in broad terms, what the “Dark Enlightenment” is all about:

Largely ignored by academic philosophers, the “Dark Enlightenment” movement and Yarvin have curried favor and influence with tech executives in recent years. (…) Not unlike the Futurists, Yarvin advocates for replacing democracy with a kind of techno-feudal state—for the government to be run like a corporation, with the president as its “CEO.” This new system is elitist—“humans fit into dominance-submission structures” Yarvin wrote in 2008; and it’s authoritarian—“If Americans want to change their government, they’re going to have to get over their dictator phobia,” he said in 2012 (…) What’s even more alarming is that Yarvin’s outsize influence on tech executives has now made its way to Washington. The signs are everywhere: Yarvin was a feted guest at Trump’s so-called “Coronation Ball” in January 2025. Vice President J.D. Vance, a protegee of Thiel’s, spoke admiringly of the blogger’s influence on his thinking when interviewed on a podcast in July 2024. And while Andreessen’s role in the Trump White House is unofficial, The Washington Post reported in January 2025 that the executive “has been quietly and successfully recruiting candidates for positions across Trump’s Washington.”

Even the journalist running the NYT interview, David Marchese, seems a bit perplexed by this growing influence. He preambles the interview with:

I’ve been aware of Yarvin, who mostly makes his living on Substack, for years and mostly interested in his work as a prime example of antidemocratic sentiment in particular corners of the internet. Until recently, those ideas felt fringe.

In another post from last year, I argued against Ross Douthat, whose argument was that the Internet was enabling a “Monoculture”. On the contrary, I said: it’s an amazingly efficient and fast incubator of new ideologies, and ideas born on the internet shall come to dominate the 21st century much more than those born in traditional institutions (note the term “ideology” — I am not including here STEM stuff). In that post, I was mostly citing examples of how rationalism had become embedded into tech culture and influenced the development of arguably the most powerful technology we have now, AI, itself. Curtis’ neoreactionary movement is just another very important example that proves my point.

If the mainstream media has been ignoring Curtis for a long time, other, at the time obscure internet writers, were not. Most notably, Scott Alexander wrote one of the first comprehensive take-downs of neoreactionary thought back in 2013: the Anti-Reactionary FAQ. In fact, back then he spent quite a lot of time arguing against proponents of this ideology.

It was for this reason that I strongly disagreed with another, more recent article in The New York Times, this time by Michelle Goldberg, titled “The vibe-shifts against the right”. This piece brings the names of 3 purportedly ex right-wingers who have changed their tune recently, in response to the Trump election. Their names? Alex Kaschuta, Richard Hanania and Scott Alexander.

I loved this interview with Steve Levitt

And what shocked to hear about James Heckman’s hate campaign. (And here I was thinking he was my favourite Chicago economist.)

Nice to see Australia’s late, great Leunig on international philosophy Twitter

Brian Klaas on schemas

Why changing minds in politics isn’t about winning arguments.

I: The Mysteries of Memory

Before you keep reading, try this experiment. Take a blank piece of paper and, in as much detail as possible, draw a $5 bill or £5 note, purely from memory.

If you do, you'll be astonished to realize how rudimentary and wrong your drawing turns out to be. These are objects that we've seen thousands of times in our lifetimes. We instantly recognize them. We have a clear sense of what they're supposed to look like. But when it comes to recreating them in granular detail, most of us are utterly useless. Our memory can recognize, but not always reproduce.

Our cognitive processing and our memories don't work the way we think they do. We tend to imagine there's some sort of file drawer within our heads, in which all sorts of information goes in, gets stored in pristine form, and then we pull it out when we need it. But that's not true...

II: What is a Schema?

The word schema comes from the Greek schēmat or schēma, which means "form." But the concept in its modern usage refers to patterns of thought that provide intellectual shortcuts for processing the information we encounter in our lives. Think of it a bit like your brain's organizational system, which structures our knowledge, old and new. To organize vast quantities of data, we need to sort everything into categories and patterns, with simplified assumptions.

The whole world we experience is, in a sense, a giant set of data. When you go for a walk, the amount of data your brain encounters is overwhelming—the shade of color on every leaf, the patterns of cracks on the sidewalk, the faces of every person you encounter, what they're wearing, and whether they smiled at you as you went past...

However, some information is important—and it needs to be retained efficiently in a format that can be useful to us later on. So, rather than remembering exactly what every office we have ever set foot in looks like, we develop a conceptual representation of what an office looks like. Then, when we remember an office, we fill in the gaps. So, even if we go into an office without a stapler on the desk, we often remember that a stapler was there later on, because that fits with our schema for an office...

This matters for politics, because it means that people have an easier time processing and retaining information that matches their worldview; that they will pay more attention to stories that affirm their mental frameworks for understanding the world; and they will even rewrite reality to match those schemas operating in their heads.

A politician can behave flawlessly, but if our schema has already typecast them as an incompetent or malicious imbecile, then no fresh facts will dig them out of that hole...

III: The Political Brain

Those who are professionally employed in politics are extremely weird relative to the rest of the population. They live and breathe politics, whereas the overwhelming majority of people rarely think about politics beyond the news headlines. While political junkies might be able to rattle off an endless array of statistics and understand the minutiae of policy, very few people devote that level of intellectual bandwidth to politics. That means that most people process political information using a lot more cognitive shorthands, making schemas exceptionally important.

Effective politicians can imbue a constellation of facts with a new meaning, providing voters with a fresh cognitive shortcut to make sense of the political world. Donald Trump is not, as he's claimed, a "stable genius," but he is extremely skilled at defining his opponents in ways that stick. In effect, he's providing voters with a new schema with which to understand the political landscape...

V: How to Use Schemas

The lesson, then, is not that fact-based arguments are meaningless in politics, but rather that facts are most effective when they're nestled within a ready-made intellectual framework for how to make sense of the world. Effective political movements use facts to reinforce schemas, but they understand that the schemas are what matter most. It's a depressing truth, but getting the right taglines, slogans, and vivid ways of presenting political opponents is often far more important than being right...

If you really want to destroy someone in politics, don't attack them with a barrage of facts and decimal points. Change the fundamental way that their own supporters perceive them. The path to political victory runs, to an astonishing degree, through psychology and neuroscience. That way true power lies.

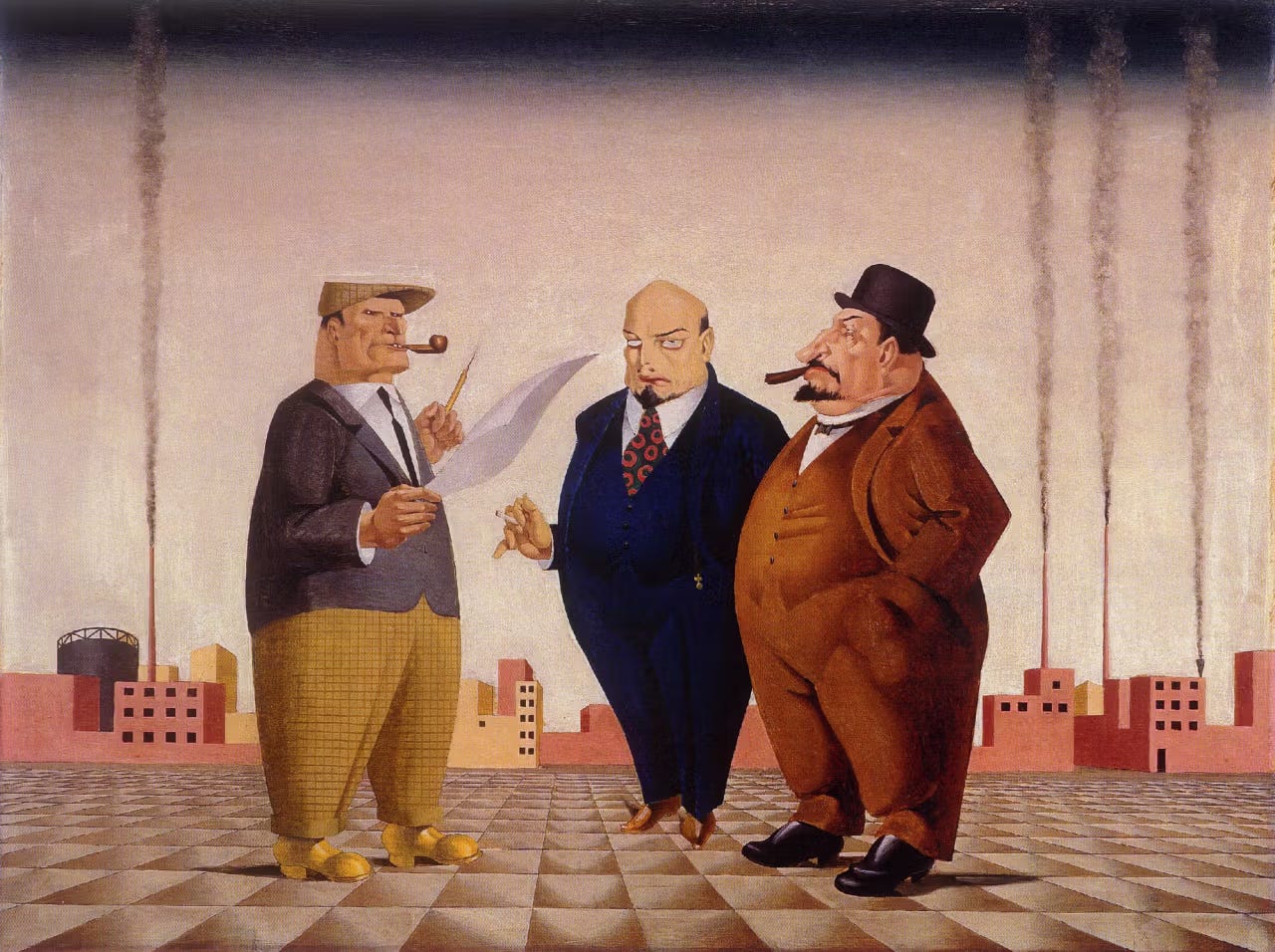

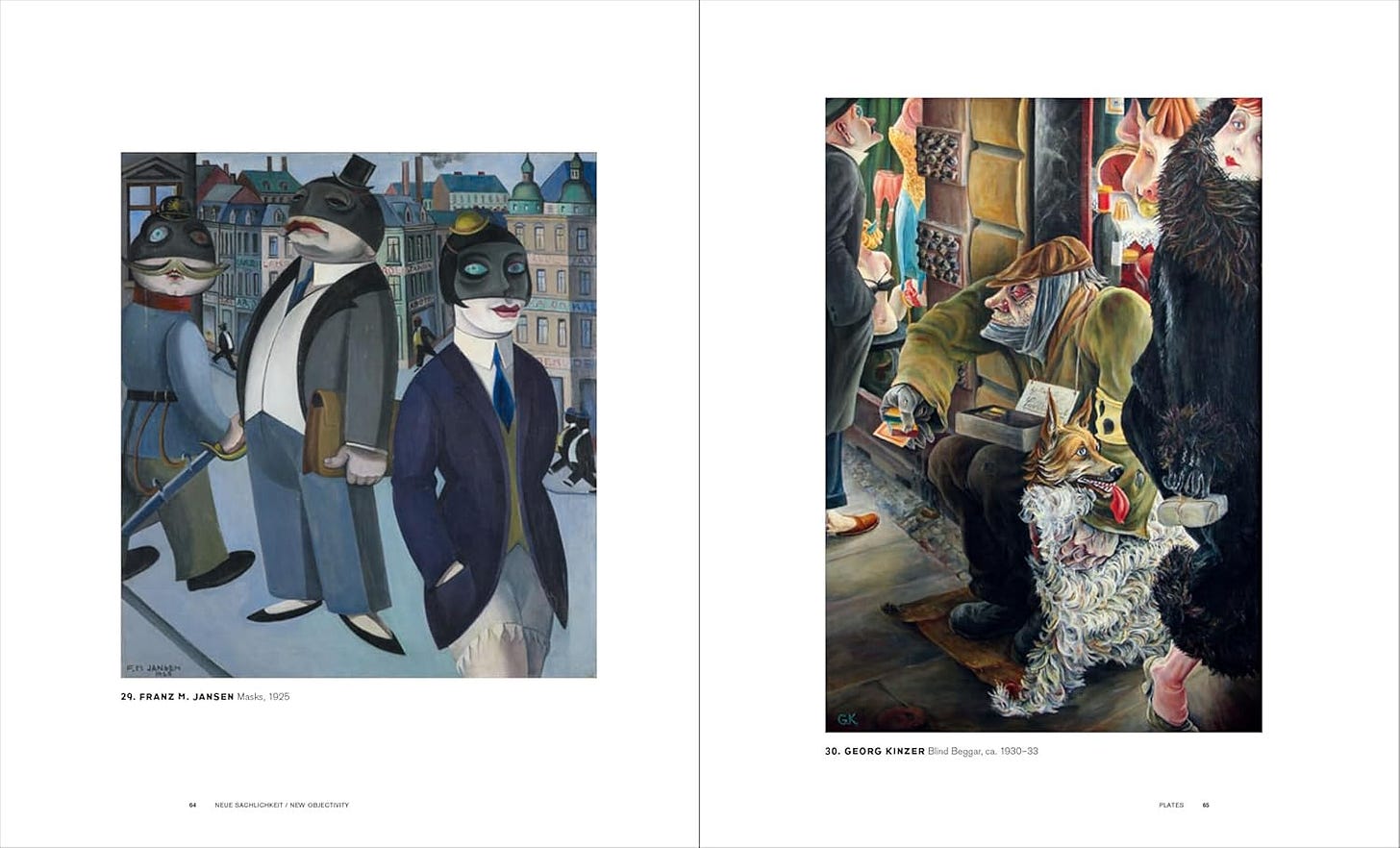

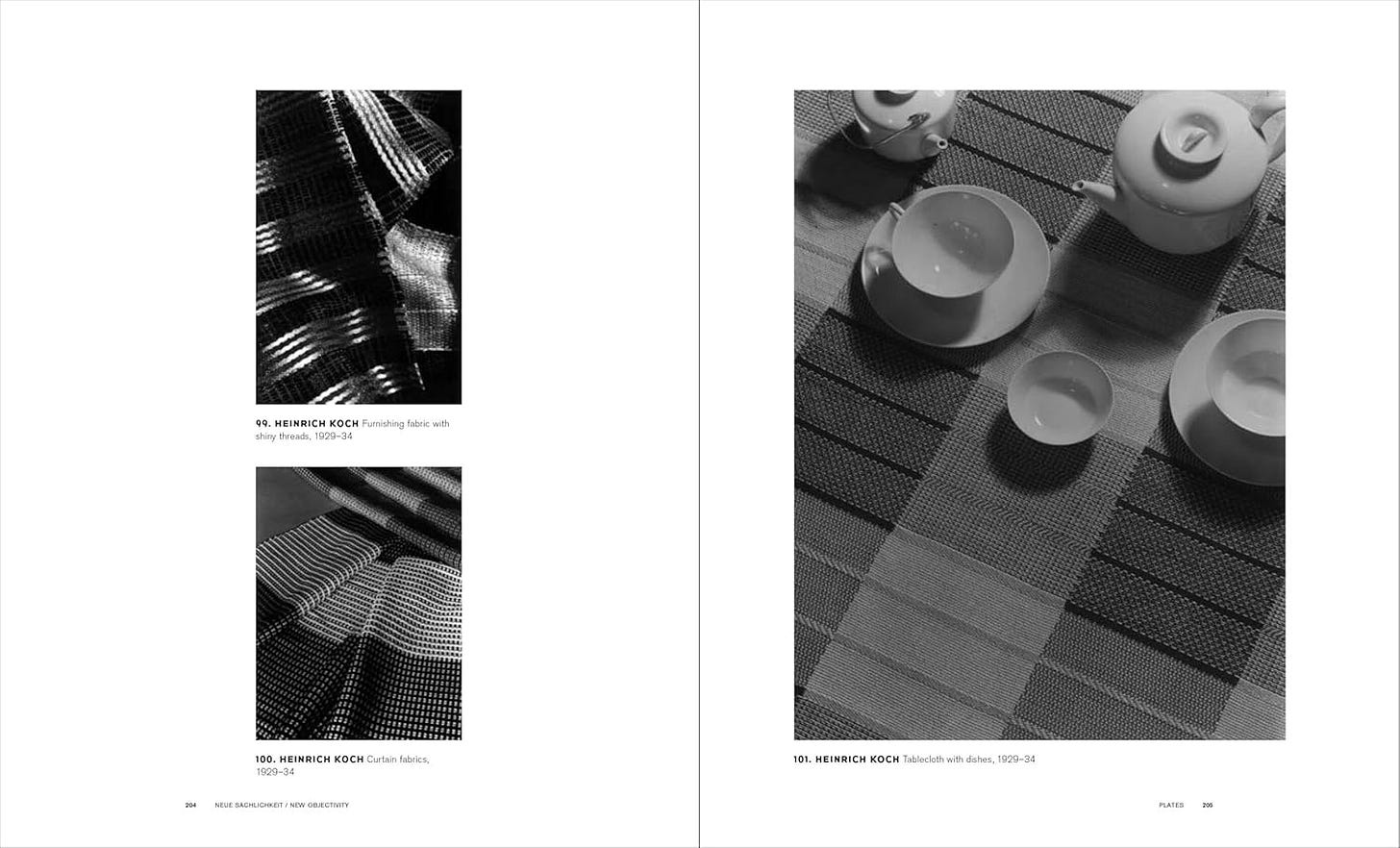

Weimar Art

Thanks to cousin Ren for his Wondercabinet newsletter which highlights all manner of things, not least art shows I’d make a beeline for if I was in NYC. Like this one.

Margaret Preston eat your heart out

What’s driving indigenous disadvantage?

A good review of Jacinta Price’s memoirs in the very terrific Inside Story. Before I extract it however, here’s a passage from Inga Clendinnen’s lyrical recreation of first contact Dancing with Strangers. (If you’ve never read it you should - you can buy it here for a song.)

“Australian interactions seen at close quarters could only erode his hopes for their quick integration into proper British ways of thinking and doing. Worst, and despite British disapproval, men continued to beat their women as of right, and then nonchalantly took them off to the hospital and Surgeon White to have their wounds and bruises dressed. Some women seemed to prefer this treatment to the sedate pleasures available in the colony. At the end of December a young girl had begged to be allowed to live among Phillip’s servants and under his protection, but she stayed for only a few days before, curiosity satisfied, she returned to her old life. Before she left she stripped off all her clothing, retaining only the woollen nightcap she had been given to keep her newly shaven head warm. Phillip drew the unavoidable inference: ‘She had never been under any kind of restraint, so that her going away could only proceed from a preference to the manner of life in which she had been brought up.’ Even young Boorong could not be kept within the settlement, however brutally she might be treated outside it. One day in the new year she came paddling in with another girl who had also enjoyed a spell under British protection, both of them hungry, both of them beaten around the head and shoulders. They said two men known in the colony had beaten them because they refused to sleep with them. And yet, after a couple of days of food and Surgeon White’s care, they paddled away again.

To be clear, I don’t think I know how to reduce indigenous disadvantage. But I have a faith that paying attention to reality will be a precondition for progress and that avoiding issues we find uncomfortable is, accordingly an irresponsible and ultimately counterproductive thing to do.

Is kinship the ethical foundation or the fatal flaw in Indigenous society? Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price has made clear that she believes social disorder is endemic to Indigenous communities, but her view is at odds with how the concept of the Indigenous family assumed a key role in the development of Indigenous land rights in Australia in the final third of the twentieth century.

Those decades saw a cascade of statutes, common law decisions and pragmatic adjustments of Australia's laws of real property — from Don Dunstan's Aboriginal Lands Trust Act of 1966 to John Howard's successful campaign to reconcile the Coalition parties to an amended Native Title Act in 1998. With bipartisan support, these policy changes resulted in a growing Indigenous land and sea estate. No government could afford to extinguish even a tiny portion of its extent by lawful means...

The national system of native title mobilises what anthropologist Peter Sutton has called "families of polity." Indigenous social order was believed to be reproducing itself, in an orderly fashion, as a system of rights and obligations that could be accommodated by our European-derived system of property.

But an alternative optic was also emerging. Australian governments incorporated the "Indigenous identifier" within their administrative routines, making it technically possible to compare Indigenous with non-Indigenous populations according to quantified characteristics, including pathologies. Comparatively high rates of domestic violence and incarceration, for instance, or large numbers of children in out-of-home care make it plausible to portray Indigenous Australia as a society in disorder.

One explanation for what came to be known as "the gap" emphasises the intergenerational effects of traumatic colonisation. It prescribes policies that recognise Indigenous collective decision-making and encourage the recovery of institutional and personal capacity. The other explanation points to Indigenous cultural traditions that have become dysfunctional within liberal, capitalist modernity. It holds individuals and communities responsible for initiating their own recovery by committing to programs of self-improvement which the state has the duty to recommend and to prescribe.

Questions about the functionality of Indigenous society also surface whenever the Indigenous land and sea estate is considered as a national asset. What kind of "resource" is it? Are Indigenous Australians trapped in it or empowered by it? And whose answers to those questions should prevail?

These questions are inflected by a "culture war" in which alternative images of Indigenous customs and laws contend. Are their customs ethically and socially sound in themselves, entitled to exist despite stubbornly colonial structures and habits of mind? Or are they flawed and maladaptive, requiring innovation and perhaps external intervention to correct or erase them?

Matters of the Heart is an intervention into this debate. In wider discussions, the question of the worth and future of Indigeneity is often posed as a question about the constitution of Indigenous domestic order — in other words, the quality of relationships between men and women and between adults and children. Price presents her family life as exemplary of what Indigenous people could be if they make the right decisions...

A key obstacle to Indigenous hopes of a better life, she has said elsewhere, is "the dysfunctionality and lack of accountability of land councils." In the Senate in February this year, she justified her attacks on the NT land councils by saying, "Well, maybe if they didn't have chairmen who had a history of domestic violence and maybe if they had removed these people or knew of their backgrounds before putting them in these places of leadership, I would stop calling them out." She then named as "perpetrators" of domestic violence four men who lead NT Aboriginal organisations.

[Price’s memoirs] Matters of the Heart is too warm and engaging in tone (and perhaps too well-vetted by lawyers) to include such specific accusations. Its political punch is more implicit in its triumphal narrative of her own domestic order — stabilised, loving and wholesome...

Price has joined the Senate's select committee on measuring outcomes for First Nations communities. One [concern] is that the "gaps" are not closing because land and sea rights are not being used to generate wealth. "Have you seen any progress in terms of improved economic conditions or the lives of those who have had access to their land once more?" she asked one witness...

Bloody Easter Bunnies!

Gauss v Pareto: Talent Versus Luck in Success and Failure

There’s no doubt that some complete morons can get rich. On the other hand, I think it’s pretty clear that each of the identifiable prime movers behind Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, Google, Palantir and Space X are exceptionally intelligent and far sighted in certain respects. (One of them - the last mentioned - is a really dreadful person in various ways and crazy to boot.) But even taking this very small and biased sample, there would be hundreds and hundreds of folks who are as clever and generally as able as them.

But these folks were in the right place at the right time, and even then, that they got lucky. There’s a lot of bright, hungry people on the east coast (they all got their start on the east coast as far as I can see - and that illustrates my point right there!) And those two curves really prove the point. Ability is distributed as a Bell Curve, market outcomes (or bureaucratic outcomes for that matter) are distributed according to a power law. The sorting of one into another is gonna have a lot of luck in it.

From the abstract of an academic article:

The largely dominant meritocratic paradigm of highly competitive Western cultures is rooted on the belief that success is mainly due, if not exclusively, to personal qualities such as talent, intelligence, skills, smartness, efforts, willfulness, hard work or risk taking. Sometimes, we are willing to admit that a certain degree of luck could also play a role in achieving significant success. But, as a matter of fact, it is rather common to underestimate the importance of external forces in individual successful stories. It is very well known that intelligence (or, more in general, talent and personal qualities) exhibits a Gaussian distribution among the population, whereas the distribution of wealth — often considered as a proxy of success — follows typically a power law (Pareto law), with a large majority of poor people and a very small number of billionaires. Such a discrepancy between a Normal distribution of inputs, with a typical scale

(the average talent or intelligence), and the scale-invariant distribution of outputs, suggests that some hidden ingredient is at work behind the scenes. In this paper, we suggest that such an ingredient is just randomness. In particular, our simple agent-based model shows that, if it is true that some degree of talent is necessary to be successful in life, almost never the most talented people reach the highest peaks of success, being overtaken by averagely talented but sensibly luckier individuals. As far as we know, this counterintuitive result — although implicitly suggested between the lines in a vast literature — is quantified here for the first time. It sheds new light on the effectiveness of assessing merit on the basis of the reached level of success and underlines the risks of distributing excessive honors or resources to people who, at the end of the day, could have been simply luckier than others. We also compare several policy hypotheses to show the most efficient strategies for public funding of research, aiming to improve meritocracy, diversity of ideas and innovation.

Liberalism as a campaign against Bonapartism

I didn’t know of Eric Schliesser until last week. A very interesting philosopher. And he argues that liberalism was born not in the toleration of Locke but in the campaign against the way in which the state was corrupted by the powerful. That’s the significance of Adam Smith’s crusade against mercantilism, and Benjamin Constant’s crusade against Bonapartism - the process by which leaders come to disguise their authoritarianism as the democratic will of the people.

As regular readers know I think it's a mistake to treat Locke as the founder of liberalism. To do so, however, is to devalue toleration as originating and intrinsic to liberalism. I have started to promote Adam Smith (alongside William Robertson) as the first to use 'liberal' in a modern sense and this allows one to emphasize liberalism as an ameliorative response to warlike and imperial, mercantile capitalism (and to celebrate federalism, moral equality, rule of law, commerce, etc.) Very sophisticated scholars scoff at this hunt for fathers and starting points, of course.

A certain knowingness surrounds the idea that Benjamin Constant is the first liberal. My own view is that there is a huge amount of Smith in Constant, but let's leave that aside. If Constant is the first liberal, then liberalism starts — and this is the important bit — not as a response to religious warfare, not as a revolt against mercantile imperialism, but against Bonapartism in (1814) The Spirit of Conquest and Usurpation.

Crucially for my purposes, for Constant Bonaparte wasn't the first Bonapartist—that was Cromwell, avant la lettre. ... We may define Bonapartism as the form of despotism that "appropriates the very [democratic] forms it violates." (p. 131; part II, chapter 14, in the Fontana translation).* To name this appropriation, Constant uses Locke's understanding of the idea of usurpation.

Usurpation as Bonapartism uses it is, thus, a kind of (violent) play-acting: "individuals are forced to pretend that they are acting solely for the advantage and the good of the people" (p. 100) because of the predominance of democratic ideas. In Bonapartism, the freedom of the press is parodied, and it forces authors to lie to their conscience. (pp. 96-7, II.3)

There is a great passage that captures the as-if nature, the counterfeiting of liberty that is so characteristic of Bonapartism: "The people will elect their magistrates, but if they fail to elect them in the way prescribed in advance, their choices will be declared null. Opinions will be free, but any opinion in opposition not only to the general system, but even to trifling circumstantial measures, will be punished as treasonable." (p. 111; part II.8)

... The Spirit of Conquest and Usurpation tells us of two Bonapartists, who usurp through democracy. This is made explicit in the context when Constant describes legitimacy: "Of the two kinds of legitimacy which I admit, the one which derives from election is more seductive in theory, but it has the inconvenience that it can be counterfeited: as it was in England by Cromwell and in France by Bonaparte." (p. 159). That Cromwell is the first Bonapartist matters because he takes power in a propertied democracy. Constant is not so naïve as to think that it can only occur in mass democracy.

There is an important contrast between the two Bonapartists: Napoleon has 'the need for war to maintain usurpation." (p. 163) Cromwell did not need this. Constant ascribes this difference to the effect of the rise of modern communication. ... On Constant's account, on the British Isles Cromwell could maintain England as a communicative echo-chamber without attacking nearby countries to prevent propaganda against him from spreading. ("Communications between peoples were neither as frequent nor as easy." (p. 164)+

... Here I want to close on the crucial point: the analysis of how (propertied) democracy is potentially self-undermining originates within liberalism. And from within liberalism 18 Brumaire is a completely predictable event.

While there is much to learn from non-liberals like Marx and Burnham (and ambivalent liberals like Weber), liberals have not ignored the rise of Bonapartism. In fact, if you think liberalism starts with Constant then liberalism has to be understood as an effort to block [the] 'road to Bonapartism.' ... It's not my take, but it is not a silly one. To be continued.

*I mean by despotism a government in which the will of the master is the only law; where political bodies, if they exist, are simply his instruments; where the master regards himself as the exclusive owner of his empire and considers his subjects merely as usufructuaries; where liberty can be taken away from the citizens without the authorities deigning to explain their motives, and without the citizens having any right to know them; where the courts are subjected to the whims of power; where their sentences can be annulled; where those who are acquitted are dragged in front of new judges, instructed, by the example of their predecessors, that they are there only to condemn. (II.9, p. 114)+

+Constant also notices linguistic barriers. In Cromwell's age the lingua franca was Latin, in Napoleon's age it was French.

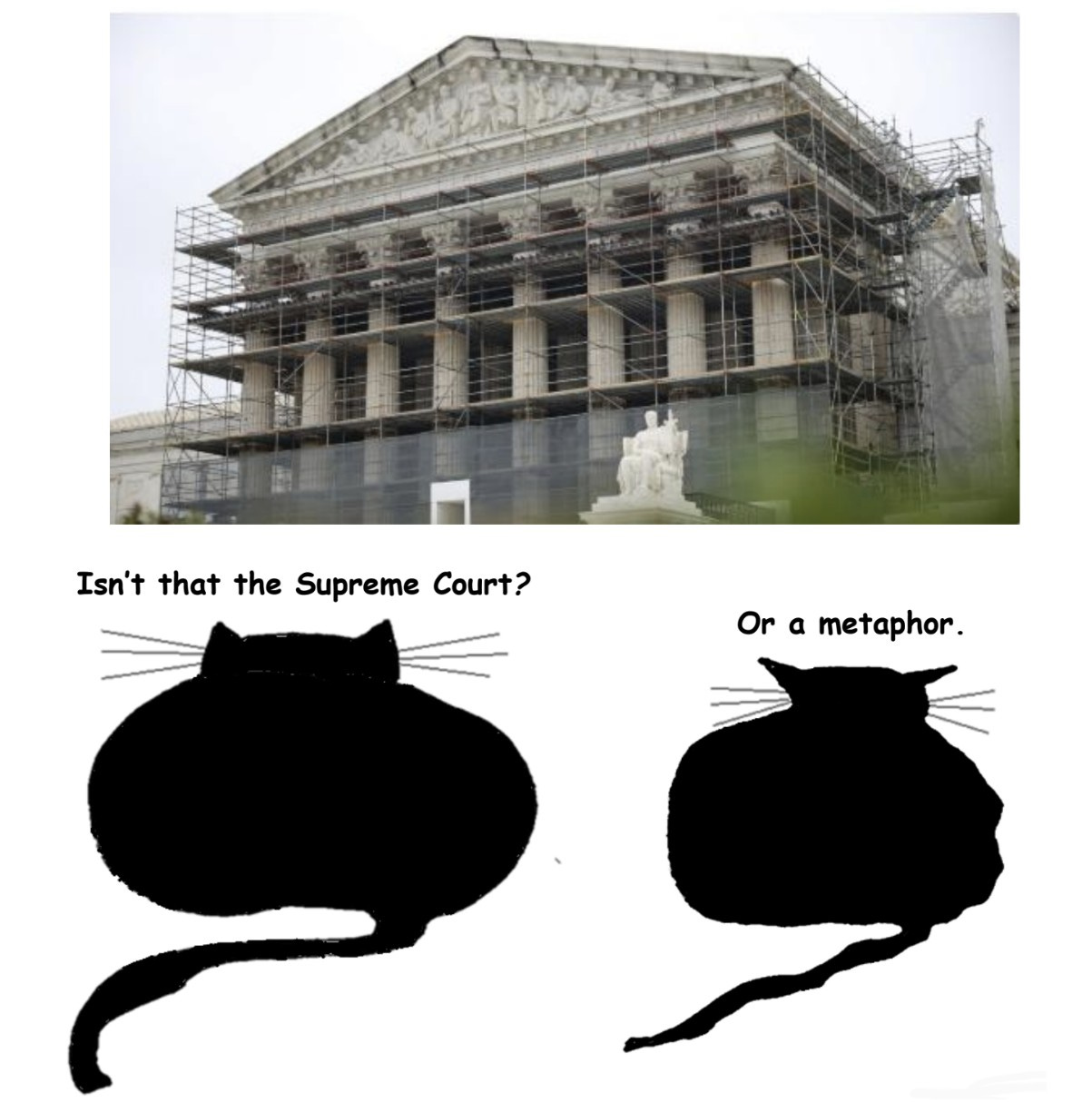

Modern Government: Oops.

Thanks to John Daley for pointing me at this article - which draws attention to something I’d drawn attention to myself. Modern government is almost invariably delivered by a pyramid of power and patronage reaching up to a single highest office.

Ancient Athens’ democracy and the Roman Republic were both built after the overthrow of tyrants and so they specifically avoided having a single highest office. And as I’ve said before, and as is being demonstrated in the US as I write this, a single point of power is a single point of failure.

III. Why one person at the top?

The delegates to the Philadelphia Convention faced a dilemma. They wanted to create an American republic, not a monarchy. But their most respected scholarly source of guidance on the new science of politics, Montesquieu,1 was clear that republics shared ultimate leadership, they did not let one person lead,2 and that republics could work only in small societies.3 Montesquieu's reasons for thinking a large society could not be a republic were not merely logistical, not just concerns that today's communications technology could overcome. More deeply, Montesquieu thought that large societies were insufficiently cohesive to be held together without one person at the helm4 and that disharmony would let a demagogue attract a mass following and use it to change the system and become a despot.5 Two millennia before, Socrates6 had noticed such a tendency in democracy more generally:

And is it not always the practice of the commons to select a special champion of their cause, whom they maintain and exalt to greatness?

Yes, it is their practice.

Then, obviously, whenever a despot grows up, his origin may be traced wholly to this championship, which is the stem from which he shoots.7

Montesquieu's solution for nurturing political liberty in large societies was constitutional monarchy – have one chief executive but hem them in with checks and balances.8

The American founders rejected Montesquieu's claim that republican government could survive only in a small society, Madison observing that "[a] citizen of Delaware was not more free than a citizen of Virginia."9 Thomas Paine later argued of Montesquieu's small republic thesis that "Montesquieu, who was strongly inclined to republican government, sheltered himself under this absurd dogma; for he had always the Bastile [sic] before his eyes when he was speaking of Republics, and therefore pretended not to write for France."10 But there was a more receptive audience among the American founders for Montesquieu's claim that republican government was intrinsically shared governance and that this should inform the structure of a republican executive as surely as a republican legislature or court.

When James Wilson proposed to the convention that "that the Executive consist of a single person,"11 Edmund Randolph countered that such a structure would be "the foetus of monarchy" and that he "could not see why the great requisites for the Executive department, vigor, despatch & responsibility could not be found in three men, as well as in one man."12 George Mason wrote in speech notes that the shared governance of true republicanism "preserves the freedom and independence of the Swiss Cantons in the midst of the most powerful nations. … If strong and extensive powers are vested in the Executive, and that executive consists only of one person, the government will of course degenerate (for I will call it degeneracy) into a monarchy … ."13 Benjamin Franklin, whose urging had elicited the debate,14 concurred, observing when the debate was over that "[t]he first man, put at the helm will be a good one. No body knows what sort may come afterwards. The Executive will be always increasing here, as elsewhere, till it ends in a monarchy."15

How could Franklin know that the first person at the helm would be a good one? Because everyone at Philadelphia knew that if they went with one chief executive, it would be George Washington.16 Washington had won the war, Washington was the elected president of their convention, and Washington was willing to serve, but only in command. "Every delegate who knew him well must have understood that Washington would neither consent to serve as one member of an executive triumvirate nor be suited for such a post."17

The Philadelphia Convention, and other constitution-drafting conventions over the two centuries since, deliberated in the millennia-long shadow of the warrior king. Weberian charismatic authority18 can be an exhilarating psychological dynamic between the person who is leader and their followers. It can help them win battles. It can help grow them from small groups into large nations through conquest. It can enable their triumph in the struggle to survive.19

The shadow of the warrior king could be seen in the explicit case made at Philadelphia for one chief executive. Echoing Montesquieu,20 Wilson argued that executive decision making distinctively required speed.21 That was true enough on a battlefield. Elbridge Gerry showed how much the battlefield analogy was on their minds when he observed that a shared executive "would be a general with three heads."22 More particularly, the comment showed how much Washington was on their minds. His ability to make snap decisions as a commander in the field had doubtless been crucial to military success. But in the field was where such speed was needed. How did it follow that a separate national chief executive would need to decide things comparably fast? Did not the success of the American colonies in the war without any such separate national chief executive show that what was needed on the battlefield was not necessarily needed in the rest of life? Cannot and should not governing decision making be more deliberative in national capitals than on battlefields? At Philadelphia, the American founders let the battlefield tail wag the governance dog.

The key explicit arguments made at Philadelphia and since for one chief executive -- energy, responsibility, and dispatch – can now be evaluated by examining how well real-life power sharing models have performed over the past two centuries. But before turning to that evaluation, we can notice that the explicit reasons offered for having one chief executive were not the only reasons in play. The shadow of the warrior king colored the conversation in ways never made explicit. It subjected the decision to a degree of path dependence, it lured to the familiar, it nurtured ambition and expectation.

Constitution-drafting conventions are mostly dominated by present and likely future leaders. Why wouldn't ambition play a part in choices to create exalted roles? Our vaunted capacities for reasoning and communication have not carried human power dynamics very far from those of our primate cousins.23 When in the wake of the Terror, French reformers briefly succeeded in bringing truly shared governance to the French executive, Thomas Paine marveled at their accomplishment: "Those who formed the Constitution cannot be accused of having contrived for themselves. The Constitution in this respect is as impartially constructed as if those who framed it were to die as soon as they had finished their work."24 At Philadelphia, all could see that Washington's support might be crucial to the new Constitution's success. Without Washington at the helm, would enough key people really recognize the Constitution as law? They needed him to champion the constitutional change fervently and actively. They needed him not to be disgruntled. When the motion for one chief executive came to a vote, Wilson prevailed over Franklin and secured the Pennsylvania delegation's support. But Washington's own Virginia delegation was split. Madison later told Thomas Jefferson that the process of deciding on the executive "was peculiarly embarrassing."25 Virginia was able to join the majority of state delegations in favor because the vote was taken when Mason was out of the room and Washington voted for himself.26 The American Presidency was created and helped carry a false ideal of singular leadership into the modern world. Hanging over the decision was the very shadow of the warrior king that the Enlightenment had sought to escape.

In choosing to have one chief executive, the American founders were reassured by Montesquieu's idealized account of England's constitutional monarchy.27 More than two centuries of democratic experience in the modern world have since shown that concentrating executive power in one person gives that person the tools to create a shadow system and capture the institutions that are supposed to check and balance the executive. Concentrating executive power in one person is a recipe for ultimately concentrating all power in one person. The checks and balances of classic separation of powers theory are not enough to liberate humanity from the potential abuses of monarchy. Those checks and balances are fatally vulnerable to shifts in shared expectations that reconverge on the one true leader. Making one person the chief executive can amount to an anointing, a de facto coronation. The key to liberating humanity from the abuses of monarchy is power sharing. Today's democracies have mostly just not taken power sharing far enough. The delegates at Philadelphia who foresaw this and advocated against making one person the chief executive have been vindicated by two centuries of comparative constitutional experience. As one delegate later wrote: "His Powers are full great, and greater than I was disposed to make them. Nor, Entre Nous, do I believe they would have been so great had not many of the members cast their eyes towards General Washington as President; and shaped their Ideas of the Powers to be given to a President, by their opinions of his Virtue. So that the Man, who by his Patriotism and Virtue, Contributed largely to the Emancipation of his Country, may be the Innocent means of its being, when He is lay'd low, oppress'd."28

Footnotes

See, e.g., on separation of powers: "The oracle who is always consulted and cited on this subject is the celebrated Montesquieu. If he be not the author of this invaluable precept in the science of politics, he has the merit at least of displaying and recommending it most effectually to the attention of mankind." JAMES MADISON, THE FEDERALIST No. 47 (1788); "The celebrated Montesquieu, speaking of them, says: 'Of the three powers above mentioned, the judiciary is next to nothing.'" ALEXANDER HAMILTON, THE FEDERALIST No. 78 (1788). ↩

MONTESQUIEU, supra note 9, at bk. 2, ch. 3, 14-15. In any republic, "the sudden rise of a private citizen to exorbitant power produces monarchy, or something more than monarchy." If that occurs in a republic, "the abuse of this power is much greater, because the laws foresaw it not, and consequently made no provision against it." (Id. at 14.) What about wartime, or other occasions when snap decisions might need to be made? When there is "immediate need of a magistrate invested with extraordinary power," a republican constitution would ensure that the singular leader did not get settled in. "In all magistracies, the greatness of the power must be compensated by the brevity of the duration. This most legislators have fixed to a year; a longer space would be dangerous, and a shorter would be contrary to the nature of government." (Id. at 14-15.) ↩

Id. at bk. 8, ch. 16, 120. ↩

In a small community, "the interest of the public is more obvious, better understood, and more within the reach of every citizen; abuses have less extent, and, of course, are less protected." Id. Jacob Levy identifies three interrelated strands to Montesquieu's small republic argument: first, that increased size causes citizens' interests to diverge; second, that increased size obscures from citizens their shared, public interest; and third, that large size involves a large military whose leadership would eclipse and ultimately displace a truly republican government. See Jacob T. Levy, Beyond Publius: Montesquieu, Liberal Republicanism and the Small Republic Thesis, 27 HIST. POL. THOUGHT 50, 50-56 (2006). ↩

In a large community, "the public good is sacrificed to a thousand private views." MONTESQUIEU, supra note 9, at bk. 8, ch. 16, 120. "In an extensive republic there are men of large fortunes, and consequently of less moderation; there are trusts too considerable to be placed in any single subject; he has interests of his own; he soon begins to think that he may be happy and glorious, by oppressing his fellow-citizens; and that he may raise himself to grandeur on the ruins of his country." Id. How would someone of large fortune use their privileged position to subvert the existing system and become a dictator? In a republic, by abusing the powers of republican office and exploiting a charismatic salience that produces a mass following, whether of civilians or soldiers or both. ↩

PLATO, THE REPUBLIC 299 (bk. 8, 565) (John Llewellyn Davies & David James Vaughan, trans., 3rd ed., 1866). ↩

Id. ↩

MONTESQUIEU, supra note 9, at bk. 11, chs. 4-6, 150-62. ↩

1 RECORDS, supra note 103, at 357-58 (Madison's notes, June 21, 1787). ↩

3 THE WRITINGS OF THOMAS PAINE 350 (Moncure Daniel Conway, ed., 1895), reprinting Paine's 1797 pamphlet The Eighteenth Fructidor. Montesquieu lent support to this suspicion by tempering his account of England's separation of powers: "Neither do I pretend by this to undervalue other governments, nor to say that this extreme political liberty ought to give uneasiness to those who have only a moderate share of it." MONTESQUIEU, supra note 9, at bk. 11, ch. 6, 162. ↩

1 RECORDS, supra note 103, at 65 (Madison's notes, June 1, 1787). ↩

Id. at 66. ↩

Id. at 112-14. ↩

Id. at 65. ↩

Id. at 103 (Madison's notes, June 4, 1787). ↩

"Since everyone presumed that Washington would become the new government's first executive, no one could conceive of the position without thinking about him in it." EDWARD J. LARSON, THE RETURN OF GEORGE WASHINGTON 141 (2015). "All testimony concurs in assuring us that an office of this magnitude would not have been created unless Washington had been intended to fill it." W. B. Lawrence, The Monarchical Principle in Our Constitution, 131 NTH. AMERICAN REV. 385, 390 (Nov. 1880). "The Duke de Rochefoucauld, in a letter to Dr. Franklin in 1789, expresses his surprise, in view of the attempts made in France to restrain the powers of the monarch, that we should have given such unlimited scope to an elective Chief Magistrate, especially to one whose reelection for life was possible." Id. at 392. ↩

LARSON, supra note 156, at 144. ↩

WEBER, supra note 88, at 46–62. Weber opined that leadership likely emerged among early humans through their recognizing and appreciating some persons' "exceptional powers or qualities. These are such as are not accessible to the ordinary person, but are regarded as of divine origin or as exemplary, and on the basis of them the individual concerned is treated as a leader." Id., at 48. ↩

Cf. CHARLES DARWIN, THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES 153 (1859) (describing natural selection as preserving "variations in some way advantageous, which consequently endure" and observing that "any form represented by few individuals will, during fluctuations in the seasons or in the number of its enemies, run a good chance of utter extinction"). ↩

MONTESQUIEU, supra note 9, at bk. 11, ch. 6, 156: "The executive power ought to be in the hands of a monarch, because this branch of government, having need of despatch, is better administered by one than by many." ↩

1 RECORDS, supra note 103, at 65 (Madison's notes, June 1, 1787) ("giving most energy dispatch and responsibility to the office"). ↩

Id. at 97 (Madison's notes, June 4, 1787). ↩

See JANE GOODALL, THE CHIMPANZEES OF GOMBE: PATTERNS OF BEHAVIOR (1986): ch. 12 ("Aggression"), 313-56 (especially 318-19, "Coalitions and Snowballing"), and ch. 15 ("Dominance"), 409-42 (especially 418-24, "Coalitions," 424-29, "Motivation and Alpha Status," and 429-36, "Loss of Rank"). ↩

PAINE, supra note 150, at 349. ↩

3 RECORDS, supra note 103, at 132 (Letter James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, Oct. 24, 1787). ↩

"On the question for a single Executive <it was agreed to> Massts. ay. Cont. ay. N.Y. no. Pena. ay. Del. no. Maryd. no. Virg. ay. (Mr. R & Mr. Blair no--Docr. Mc. Cg. Mr. M. & Gen W. ay. Col. Mason being no, but not in house, Mr. Wythe ay but gone home). N. C. ay. S.C. ay. Georga. ay. [Ayes--7; noes--3.]" 1 RECORDS, supra note 103, at 97 (Madison's notes, June 4, 1787). ↩

MONTESQUIEU, supra note 9, at bk. 11, ch. 6, 151-62. ↩

3 RECORDS, supra note 103, at 302 (Letter Pierce Butler to Weedon Butler, May 5, 1788). ↩

More Venkatesh on AI

A sampling of posts, which all seem unpaywalled. Some remarkable prognostications on AI.

The Ecstasy of Influence: A Plagiarism

In a 2007 article, The Ecstasy of Influence: A Plagiarism, published in Harper's, Jonathan Lethem delivered a great polemic against a narrow-minded view of authors' rights, plagiarism, and claims to originality. A key passage is worth quoting in full:

Despite hand-wringing at each technological turn — radio, the Internet — the future will be much like the past. Artists will sell some things but also give some things away. Change may be troubling for those who crave less ambiguity, but the life of an artist has never been filled with certainty.

The dream of a perfect systematic remuneration is nonsense. I pay rent with the price my words bring when published in glossy magazines and at the same moment offer them for almost nothing to impoverished literary quarterlies, or speak them for free into the air in a radio interview. So what are they worth? What would they be worth if some future Dylan worked them into a song? Should I care to make such a thing impossible?

Any text is woven entirely with citations, references, echoes, cultural languages, which cut across it through and through in a vast stereophony. The citations that go to make up a text are anonymous, untraceable, and yet already read; they are quotations without inverted commas. The kernel, the soul — let us go further and say the substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material of all human utterances — is plagiarism.

The knowledgeable reader will notice that Lethem's title is derived from Harold Bloom's classic The Anxiety of Influence, as mine is from his...

LLMs and Creative Rights

Now, why is all this relevant? It is relevant because a deeply disingenuous literary/artistic reaction is taking shape in response to the rise of LLMs — casting the very creation of LLMs as constituting "theft" of some sort, while at the same time constructing human use of inherited traditions and broader textual cultures as somehow not just above reproach, but in some way constituting an honoring of a sacred tradition. When a writer rips off another writer without acknowledgment or even consciousness, it is homage within a tradition. When a programmer digests the same text into the weights of an LLM, a crime has been committed.

This is not so much a double standard as a sense of sacred/profane distinctions born of a sense of ownership of language itself on the part of those who self-consciously try to make art with it, or cultivate tastes concerning it...

Yes, a couple of million words of my own writings are now in the bellies of all the LLMs, including writings I make money from. In fact, when an LLM does not know about something I've written (because it's paywalled, or only in an offline book for example), I find myself getting annoyed about it. If it were easy, I'd simply submit everything I write directly to some sort of LLM-accessible portal...

AI-Assisted Fiction

Let me share an example of the sort of power that gets unleashed when you take a deeply liberal attitude towards LLMs. Last week, in Protocolized, I published a story called The Signal Under Innsmouth.

This has been my best attempt at AI-assisted fiction writing to date, and also one of the easiest. I simply fed the original story (The Shadow Over Innsmouth, a cult classic which Lovecraft wrote in 1937, so it's in the public domain — not that I'd have hesitated if it hadn't) to ChatGPT and asked it to transpose it to a transhumanist key, creating a kind of uncanny transhumanist horror instead of a cosmic horror. Then, with surprisingly few nudges and tweaks, I got the story linked above.

This is probably a better story than any fiction I have written unaided. It is really good, if I do say so myself...

Is it "a plagiarism" in Jonathan Lethem's sense?

Yes, and?

The Lethem Sea

To me, "LLMing" a piece of writing belongs categorically with behaviors like dictionary-use, Googling for background research, or using a spellchecker.

Or heck, reading.

If you use language at all, you belong in what we might call the Lethem Sea (in the spirit of the idea of the Dirac Sea in physics). Your "original" thoughts, ideas, and creations, in a very deep sense, aren't, in the sense that copyright-obsessed industrial modernity understands originality, attribution, provenance, and credit. They are original in the sense that you bring something of your individual lived uniqueness to how you transform what you suck up from the Lethem sea, and regurgitate into it. You're "original" in the sense a drop of water thrown up waves on the surface of the sea is "original"...

On "Slop" and the Future of Writing

I'll dismiss [AI-assisted writing] if I sense that it is slop in my pejorative sense — suffering from a deficit of human mindful attention and caring in the creation.

Pretty soon, it will be the safe default assumption, kinda like you assume everything you read written by living authors is probably spell-checked and Googling-supported.

AI is an all-or-nothing type technology, and it is already obvious to me it's going to be part of all the writing I do for the rest of my life. All my unfinished projects are either going to get abandoned, or get completed with LLM help.

This makes it all the more important to get attuned to the real slop and call it out wherever you see it. The slop of disingenuous intentions, authorial bad faith, and where LLMs are used, a disrespectful relationship with both the tools of creativity, and the cultural heritage of language. The slop of mindlessness and inattentiveness. The slop of not caring. And in my experience so far, this is universally caused by humans.

Heaviosity half hour

Hannah Arendt on Israel, 1948

A fascinating and prophetic article I came across. It was in the US magazine Commentary in May 1948 just after the establishment of the state of Israel.

To save the Jewish Homeland

When, on November 29, 1947, the partition of Palestine and the establishment of a Jewish state were accepted by the United Nations, it was assumed that no outside force would be necessary to implement this decision.

It took the Arabs less than two months to destroy this illusion and it took the United States less than three months to reverse its stand on partition, withdraw its support in the United Nations, and propose a trusteeship for Palestine. Of all the member states of the United Nations, only Soviet Russia and her satellites made it unequivocally clear that they still favored partition and the immediate proclamation of a Jewish state.

Trusteeship was at once rejected by both the Jewish Agency and the Arab Higher Committee. The Jews claimed the moral right to adhere to the original United Nations decision; the Arabs claimed an equally moral right to adhere to the League of Nations principle of self-determination, according to which Palestine would be ruled by its present Arab majority and the Jews be granted minority rights. The Jewish Agency, on its part, announced the proclamation of a Jewish state for May 16, [1948,] regardless of any United Nations decision. It remains a fact, meanwhile, that trusteeship, like partition, would have to be enforced by an outside power.

A last-minute appeal for a truce, made to both parties under the auspices of the United States, broke down in two days. Upon this appeal had rested the last chance of avoiding foreign intervention, at least temporarily. As matters stand at this moment, not a single possible solution or proposition affecting the Palestinian conflict is in sight that could be realized without enforcement by external authority.

The past few weeks of guerrilla warfare should have shown both Arabs and Jews how costly and destructive the war upon which they have embarked promises to be. In recent days, the Jews have won a few initial successes that prove their relative superiority over present Arab forces in Palestine. The Arabs, however, instead of concluding at least local truce agreements, have decided to evacuate whole cities and towns rather than stay in Jewish-dominated territory. This behavior declares more effectively than all proclamations the Arab refusal of any compromise; it is obvious that they have decided to expend in time and numbers whatever it may take to win a decisive victory. The Jews, on the other hand, living on a small island in an Arab sea, might well be expected to jump at the chance to exploit their present advantage by offering a negotiated peace. Their military situation is such that time and numbers necessarily work against them. If one takes into account the objective vital interests of the Arab and the Jewish peoples, especially in terms of the present situation and future well-being of the Near East—where a full-fledged war will inevitably invite all kinds of international interventions—the present desire of both peoples to fight it out at any price is nothing less than sheer irrationality.

One of the reasons for this unnatural and, as far as the Jewish people are concerned, tragic development is a decisive change in Jewish public opinion that has accompanied the confusing political decisions of the great powers.

The fact is that Zionism has won its most significant victory among the Jewish people at the very moment when its achievements in Palestine are in gravest danger. This may not seem extraordinary to those who have always believed that the building of a Jewish homeland was the most important—perhaps the only real—achievement of Jews in our century, and that ultimately no individual who wanted to stay a Jew could remain aloof from events in Palestine. Nevertheless, Zionism had in actuality always been a partisan and controversial issue; the Jewish Agency, though claiming to speak for the Jewish people as a whole, was still well aware that it represented only a fraction of them. This situation has changed overnight. With the exception of a few anti-Zionist die-hards, whom nobody can take very seriously, there is now no organization and almost no individual Jew that doesn't privately or publicly support partition and the establishment of a Jewish state.

Jewish left-wing intellectuals who a relatively short time ago still looked down upon Zionism as an ideology for the feebleminded, and viewed the building of a Jewish homeland as a hopeless enterprise that they, in their great wisdom, had rejected before it was ever started; Jewish businessmen whose interest in Jewish politics had always been determined by the all-important question of how to keep Jews out of newspaper headlines; Jewish philanthropists who had resented Palestine as a terribly expensive charity, draining off funds from other "more worthy" purposes; the readers of the Yiddish press, who for decades had been sincerely, if naïvely, convinced that America was the promised land—all these, from the Bronx to Park Avenue down to Greenwich Village and over to Brooklyn, are united today in the firm conviction that a Jewish state is needed, that America has betrayed the Jewish people, that the reign of terror by the Irgun and the Stern groups is more or less justified, and that Rabbi Silver, David Ben-Gurion, and Moshe Shertok are the real, if somewhat too moderate, statesmen of the Jewish people.

Something very similar to this growing unanimity among American Jews has arisen in Palestine itself. Just as Zionism had been a partisan issue among American Jews, so the Arab question and the state issue had been controversial issues within the Zionist movement and in Palestine. Political opinion was sharply divided there between the chauvinism of the Revisionists, the middle-of-the-road nationalism of the majority party, and the vehemently antinationalist, antistate sentiments of a large part of the kibbutz movement, particularly the Hashomer Haza'ir. Very little is now left of these differences of opinion.

The Hashomer Haza'ir has formed one party with the Ahdut Avodah, sacrificing its age-old binational program to the "accomplished fact" of the United Nations decision—a body, by the way, for which they never had too much respect when it was still called the League of Nations. The small Aliyah Hadashah, mostly composed of recent immigrants from Central Europe, still retains some of its old moderation and its sympathies for England, and it would certainly prefer Weizmann to Ben-Gurion—but since Weizmann and most of its members have always been committed to partition, and, like everybody else, to the Biltmore Program, this opposition does not amount to much more than a difference over personalities.

The general mood of the country, moreover, has been such that terrorism and the growth of totalitarian methods are silently tolerated and secretly applauded; and the general, underlying public opinion with which anybody desiring to appeal to the yishuv has to reckon shows no notable divisions at all.

Even more surprising than the growing unanimity of opinion among Palestinian Jews on one hand and American Jews on the other is the fact that they are essentially in agreement on the following more or less roughly stated propositions: the moment has now come to get everything or nothing, victory or death; Arab and Jewish claims are irreconcilable and only a military decision can settle the issue; the Arabs—all Arabs—are our enemies and we accept this fact; only outmoded liberals believe in compromises, only philistines believe in justice, and only schlemiels prefer truth and negotiation to propaganda and machine guns; Jewish experience in the last decades—or over the last centuries, or over the last two thousand years—has finally awakened us and taught us to look out for ourselves; this alone is reality, everything else is stupid sentimentality; everybody is against us, Great Britain is antisemitic, the United States is imperialist—but Russia might be our ally for a certain period because her interests happen to coincide with ours; yet in the final analysis we count upon nobody except ourselves; in sum—we are ready to go down fighting, and we will consider anybody who stands in our way a traitor and anything done to hinder us a stab in the back.

It would be frivolous to deny the intimate connection between this mood on the part of Jews everywhere and the recent European catastrophe, with the subsequent fantastic injustice and callousness toward the surviving remnant that were thereby so ruthlessly transformed into displaced persons. The result has been an amazing and rapid change in what we call national character. After two thousand years of "Galuth mentality," the Jewish people have suddenly ceased to believe in survival as an ultimate good in itself and have gone over in a few years to the opposite extreme. Now Jews believe in fighting at any price and feel that "going down" is a sensible method of politics.