Blessed are the nutcases …

And other great things I found on the net this week

Blessed are the narcissistic, rage-filled Baptists

Blessed are Stalin, Mao and Hitler: they didn’t get everything right but they were nobody’s mug

Filed under “OOPS”.

I’ve been had

Last week I published an extract from a Quillette article which reported on the state two years on from the discovery of what seemed to be 215 unmarked graves for Indigenous children who were wards of the state. The article points out that:

During this entire period, not a single unmarked grave, body, or set of remains is known to have been found at Kamloops, nor at any of the other First Nations communities that conducted similar ground-penetrating radar surveys.

I assumed it was generally truthful given passsages like this, which I also extracted.

I was one of the many Canadians who believed these headlines. The racist abuses meted out by Canada’s 19th- and 20th-century-era residential-school system, which had been created to “civilize” Indigenous people and strip them of their culture, has been widely discussed for decades. Given this dark history, it wasn’t hard to believe that some of the priests and educators who ran these schools hadn’t just been cruel and negligent (this much was already known), but also had committed acts of mass murder against defenceless children.

Many of its points are reasonable enough — and indeed I agree with them. Particularly the way in which simple truth seeking is stigmatised as racist. This kind of weaponisation of the facts on which we build our opinions seems disastrous.

On the other hand, however literally true the article’s facts are, they’re tendentiously true. There are, in the immortal words of the deranged and very clever Kelly-Anne Conway “alternative facts”. Namely that there are plenty of unmarked graves that have Indigenous kids bodies in them as reported in Wikipedia. That having been said, confirmed unmarked graves are in the hundreds while those suspected from ground penetrating radar are in the thousands. At Kamloops which was the source of the excitement no physical investigation has been approved by the locals, and so, unsurprisingly, no bodies have been uncovered, though I’m not so naïve as to believe that such decisions don’t have their own political backstory. In hindsight I think the article I extracted could have made its points in a more balanced way.

You might also be interested in reading an interesting article I found in investigating this. These are its concluding paragraphs:

There's another strong memory Paul has from residential school.

She recalls often having to attend church after being beaten. The children would be spanked for falling down after kneeling on hardwood floors for hours, she said.

But she was enchanted by the piano in church.

"I didn't understand the beatings. I was just getting beat every day, it's part of you and I was fed up. Something told me to play the piano and I started to learn and play during mass."

Some of her family members were musical, and playing and singing fascinated her. In the residential school church, she remembers standing next to the piano. Finally, a nun agreed to teach her.

She learned by listening and watching others play. She was a natural and fell in love with playing.

"You can imagine yourself so far away — like you're free. And I would just focus on playing all the time because I needed to get away from there. I didn't have the harsh realities anymore of getting beaten every day."

It’s come to this

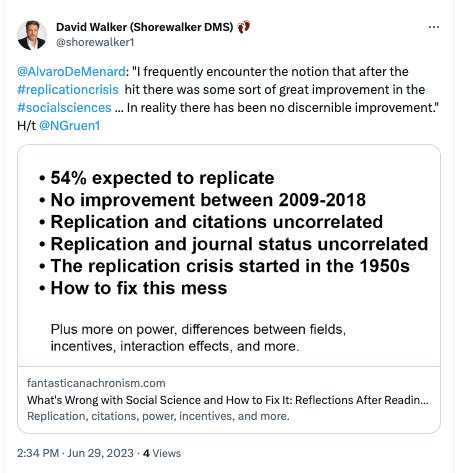

Once more with feeling: devastating review of the corruption of academia

Uncomfortable collisions with reality

How did we get from "How Can I Help" to "How Can Govt Help Me?

A couple of months ago I read and admired this article on Palladium, a new(ish) website that “explores the future of governance and society through international journalism, long-form analysis, and social philosophy”. It seemed that there was sufficient overlap between its concerns and mine that I asked if the author, Tanner Greer, would join me on the podcast

The essay begins with this assertion:

The first instinct of the nineteenth-century American was to ask, “How can we make this happen?” Those raised inside the bureaucratic maze have been trained to ask a different question: “How do I get management to take my side?”

It then elaborates and explores with examples, speculates on the causes of the change and discusses the means by which we might get back to a healthier situation. Greer argues that the 19th-century institutions combined three characteristics: the aspirational ideal of public brotherhood, a commitment to formality and discipline in self-government, and organizational structures that combined decentralization with hierarchy. I hope you enjoy the discussion. I think the last two thirds of the discussion are the best and have programed the video to start from there.

If you’d rather just listen to the audio, it is here.

Something Was Messing With Earth’s Axis.

The Answer Has to Do With Us.

Thanks to DG for alerting me to this.

Around the turn of the millennium, Earth’s spin started going off-kilter, and nobody could quite say why.

For decades, scientists had been watching the average position of our planet’s rotational axis, the imaginary rod around which it turns, gently wander south, away from the geographic North Pole and toward Canada. Suddenly, though, it made a sharp turn and started heading east.

In time, researchers came to a startling realization about what had happened. Accelerated melting of the polar ice sheets and mountain glaciers had changed the way mass was distributed around the planet enough to influence its spin.

Now, some of the same scientists have identified another factor that’s had the same kind of effect: colossal quantities of water pumped out of the ground for crops and households.

Great podcast with Andrew Gelman: from the Econtalk archive

How Brian Klaas Won a Disinformation Battle — But Lost the War

A nice little morality tale in which the table above is the moral. If you’re up against a the Hunter Biden distraction, refute it as best you can and get onto your point. Otherwise the debate centres on the disinformation of your opponent

Andy Haldane explains some important things: Brad Delong thinks he should have lent in more

Andy Haldane: The global industrial arms race is just what we need: ‘Manufacturing is undergoing a revival around the world, sending several secular trends into reverse…. The past few years, however, have seen… three distinct global arms races. The first centres on green technologies and industries…. With an extra investment of around 2-3 per cent of global gross domestic product per year in green technologies needed to hit net zero, this race has a distance to run. These initiatives have drawn criticism on the grounds they amount to a subsidy race. But an arms race to invest in decarbonising technologies is in fact exactly what the world needs to tackle two global externalities—the climate crisis and the investment drought…. The second global arms race under way is remilitarisation. After a period of decline, heightened geopolitical tensions, amplified by the war in Ukraine, have caused governments globally to reinvest in defence… reigniting manufacturing in both east and west. Third… to re- or on-shore manufacturing…. motivated by the need for greater supply chain resilience in the wake of Covid-19, but also by a desire for local job re-creation…. These arms races are beginning to transform the contours of global policy and the global economy…. Public and private money is flooding into manufacturing projects, irrigating firms dehydrated by the investment drought…. Most arms races leave no one better off. Today’s race to reindustrialise is different. It may be just the impetus the world needs to break free of its economic and environmental torpor…

Andy Haldane could have put his argument more strongly, had he identified the externalities that the subsidy plans now ramping up would compensate for:

There is no market to pay for “insurance” against global value-chain disruption. The Covid-19 pandemic has shown us how vulnerable our global supply chains can be, and the need for greater resilience in the face of such disruptions. By investing in re- or on-shoring manufacturing, governments can help to mitigate the risks associated with global value-chain disruption.

Xi Jinping’s China looks scarily like pre-WWI Wilhelmine Imperial Germany in its desire to throw its weight around internationally to distract its citizens from the government’s domestic problems. This has led to heightened geopolitical tensions and makes proper the renewed focus on defense spending. Governments need to maintain the peace by greatly discouraging adventurist wars and rumors of war like that launched by Xi Jinping’s “no limits” partner, Vladimir Putin of Muscovy.

here are enormous positive technological externalities produced by the communities of engineering practice associated with manufacturing. By investing in manufacturing, governments can help to foster innovation and technological advancement, which can have far-reaching benefits for society as a whole.

4. There is the refusal of right-wing grifters to allow proper pollution pricing, especially in the case of global warming. This has led to a failure to adequately address the climate crisis and the need for urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. By investing in green technologies and industries, governments can help to drive the transition to a low-carbon economy and mitigate the worst impacts of climate change.

John Cleese bells the cat

It appears to have taken John Cleese longer than it took some friends of mine to realise that the royal family was the template for Monty Python.

Unhinged and unleashed: Depravity masquerading as reason itself

A mainstream intellectual voice in Russia:

It is necessary to arouse the instinct of self-preservation that the West has lost and convince it that its attempts to wear Russia out by arming Ukrainians are counterproductive. We will have to make nuclear deterrence a convincing argument again by lowering the threshold for the use of nuclear weapons set unacceptably high, and by rapidly but prudently moving up the deterrence-escalation ladder. The first steps have already been made …. But there are many. … Things may also get to the point when we will have to urge our compatriots and all people of goodwill to leave their places of residence near facilities that may become targets for strikes in countries that provide direct support to the puppet regime in Kiev. The enemy must know that we are ready to deliver a preemptive strike in retaliation for all of its current and past acts of aggression in order to prevent a slide into global thermonuclear war.

I have said and written many times that if we correctly build a strategy of intimidation and deterrence and even use of nuclear weapons, the risk of a “retaliatory” nuclear or any other strike on our territory can be reduced to an absolute minimum. Only a madman, who, above all, hates America, will have the guts to strike back in “defense” of Europeans, thus putting his own country at risk and sacrificing conditional Boston for conditional Poznan. Both the U.S. and Europe know this very well, but they just prefer not to think about it. We have encouraged this thoughtlessness ourselves with our own peace-loving rhetoric. From studying the history of the American nuclear strategy I know that after the USSR had gained the convincing ability to respond to a nuclear strike, Washington did not seriously consider, although bluffed in public, the possibility of using nuclear weapons against Soviet territory. …

We must go up the deterrence-escalation ladder quickly enough. Given the vector of Western development ― the persistent degradation of most of its elites―each of their next calls will be even more incompetent and more ideologically charged than the previous ones. We can hardly expect more responsible and reasonable leaders to come to power there in the near future. This can happen only after a catharsis, after they have given up their ambitions.

We must not repeat the “Ukrainian scenario.” For a quarter of a century, we did not listen to those who warned that NATO expansion would lead to war, and tried to delay and “negotiate.” As a result, we have got a severe armed conflict. The price of indecision now will be higher by an order of magnitude.

But what if they do not back down? What if they have lost the instinct of self-preservation completely? In this case we will have to hit a bunch of targets in a number of countries in order to bring those who have lost their mind to reason.

Turning up for the cameras

A fairly clear illustration of a process well anatomised by Ezra Klein in his book Why we’re polarised which I outline below.

In September 2009 South Carolina Republican Congressman Joe Wilson, interrupted a televised address to Congress by President Obama. “You lie!” he shouted, although Obama was speaking truthfully. Republican grandees like John McCain deplored this historic breach of decorum and respect for the presidency and managed to elicit an apology of sorts. But Wilson’s public pugnaciousness took him from the backbench to celebrity overnight. He raised US$2 million in donations (much of it from around the country, not from his constituency) and became a Republican fund-raising asset around the country. His Democrat opponent Rob Miller then raised three quarters of that amount on the back of the publicity, the two men went to the next election more than doubling the expenditure of all other candidates in South Carolina.

Politicians at the cutting edge of increasing polarisation are rewarded with publicity (both good and bad), profile, status and fundraising prowess. In a competitive system, Gresham’s Law is setting off its usual race to the bottom. And this matters, obviously enough, for the capacity of democracies to govern themselves well. Perhaps even more alarming at a time of growing international threats — from military tension between countries with devastating nuclear arsenals to environmental breakdown and global pandemics — competitive forces in democratic politics are imposing increasing disciplines on politicians to pander to their bases and flatter their audiences.

Speaking of depravity masquerading as reason

From Harpers, by Jackson Lears, whom Wikipedia tells us is “an American cultural and intellectual historian with interests in comparative religious history, literature and the visual arts, folklore and folk beliefs”. He’s also a Vietnam vet whose service played an important role in his views on war:

Among many other things, my experience in San Diego taught me how official secrecy undermines truth-telling—which in turn undermines democracy. During my Conscientious Objection application, the executive officer’s assistant informed me that my reference to [my ship’s] the Chicago’s nuclear weapons had to be removed because the Navy’s policy was to deny that those missiles were nuclear-armed. “Why, probably three-quarters of the people of San Diego don’t know we carry nukes,” he said. I realized then that the most dangerous purveyors of disinformation were not conspiracy theorists but the military, the intelligence agencies, and their stenographers in the mainstream press.

Still, the public discourse of the Seventies seems crystalline compared to the murk produced by our contemporary media. In the late Sixties, distrust of government-produced disinformation was already on the rise, fueled by truth-tellers like Ellsberg, I. F. Stone, and Seymour Hersh, who exposed the systematic mendacity of the military and the intelligence agencies.

But after the humiliating withdrawal from Saigon in 1975, political fashions changed. Policymakers fretted that a “Vietnam Syndrome” would discourage military interventions overseas; major newspapers, led by the New York Times, announced that the public’s right to know had to be balanced against the government’s need to keep secrets. Meanwhile, the architects of war continued a trend that had begun under Kennedy, moving away from deterrence and toward a more flexible development of tactical nuclear weapons. What energized this shift was the technocratic dream of precise control over war—the least predictable of human enterprises. …

Yet there was pushback. … The Nuclear Freeze movement was a popular uprising that garnered support across the country. It helped create a mass audience for the 1983 TV movie The Day After, which powerfully evoked the impact of a nuclear strike on a Kansas town from instant incineration to the slow, painful death by radiation sickness, reminding some hundred million viewers what was actually at stake. Addressing a panel of experts assembled by ABC to discuss the film, Henry Kissinger sneered and sputtered. But Reagan watched it [and] wrote in his diary: “My own reaction was one of our having to do all we can to have a deterrent & to see there is never a nuclear war.”

On January 16, 1984, he delivered a speech insisting that the United States and the Soviet Union had “common interests, and the foremost among them is to avoid war and reduce the level of arms.” He further declared his support for “a zero option for all nuclear arms.” It is an arresting experience to read these words, coming from a man who had so recently committed himself to a moral crusade against an evil Soviet empire. It is also arresting because it is nearly impossible to imagine these words coming from the White House today. Reagan’s speech was written in the classic language of diplomacy—the recognition of interests shared by rivals, who may disapprove of each other’s actions but who need to agree to protect the general good. The speech’s author, Jack F. Matlock Jr., later became Reagan’s ambassador to the Soviet Union, and is now one of the few voices calling for diplomats to end the war in Ukraine. Matlock insists that, whatever domestic political aims the speech may have served, it was meant to be taken seriously by Soviet leaders. …

The war in Ukraine has brought [nuclear weapons] back into the public square. But to the extent that these weapons are discussed at any length, it is in the bland language of policy expertise. The moral and human meanings of nuclear warfare have disappeared behind a veil of indifference, while the U.S. insistence on total Ukrainian victory—even contemplating a recapture of Crimea—makes a nuclear exchange ever more likely. So does the increasing number of U.S. bombers on crisis alert in Eastern Europe, and the technocratic rationality that masks the madness of the nuclear strategists at the Hoover Institution and other think tanks.

The gravity of our situation is revealed in the U.S. Nuclear Posture Review, which was most recently updated in October 2022. The latest statement affirms U.S. opposition to a “No First Use” policy; it also asserts the validity of using nuclear weapons “in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its Allies and partners.” By implicitly leaving open the possibility of first use, the policy allows the United States to cross the nuclear threshold for something as vague as an ally’s “vital interests.” One could hardly ask for more permissive criteria. …

These statements confirm a chilling conclusion: nuclear war is being normalized as part of a broader U.S. foreign policy of perpetual confrontation with actual or imagined rivals. Even during the darkest days of the Cold War, both sides recognized the immense threat posed by nuclear war, and the common interest they shared in avoiding it. But diplomacy has disappeared from U.S. foreign policy, which remains mired in moral rigidity. …

Ellsberg urges the dismantling of the Doomsday Machine—the huge arsenal of missiles possessed by both Russia and the United States—that can kill, maim, and sicken hundreds of millions on impact. … Avoiding doomsday would not require decommissioning all nuclear weapons—we might preserve enough to deter any potential attack, pending the ultimate goal of abolition. But amid the current war fever, it is impossible to imagine the United States beginning to dismantle any weapons, and that is a tragedy. For the dance of death to stop, one of the partners must step aside.

Martin Wolf on inflation

Though Martin Wolf has moved to the left from what I think he’d describe as a right-of-centre position, he still remains a hardliner on inflation whose instincts have so far proven prescient. It’s not an area I’d want to express any strong opinions on, but I would make the following observations.

The inflation spike occurred as a result of a supply shock, so there was a good case for being careful at least early on as there are plenty of instances of a price spike passing through economies and their returning to the long run, low inflation trajectory they started out from.

That supply shock was mostly from supply chain disruptions for manufactured goods as a result of the COVID shock and food and energy prices as a result of the Ukraine war.

Left of centre commentators have made much of this fact. They also point out that real wages have fallen sharply as prices have risen. This is all true and in a sense suggests that the necessary micro-economic adjustment is being made to our need to restrain our consumption to a world in which the commodities I mentioned above have become scarcer. However:

The labour market is very tight creating the risk of price rises feeding into an inflationary spiral. That’s the problem. We don’t have well targeted ways of halting this spiral. A general economic slowdown is the main tool in the orthodox toolkit. in the 1980s Australia followed some European countries in a kind of corporatist macro-bargaining model under the Accord which reduced inflation but did not get it into the target band we are today familiar with. But in Australia no-one among the Very Serious Folks have suggested doing that.

Given all this, in principle, temporary price controls and/or windfall taxes might be able to make a contribution to maximising the efficiency and equity of the transition we need to make. You heard it first here (Ok — maybe not first, but you heard it, or read it). Even so, there are some dangers associated with this — our political system isn’t noted for its subtlety, and the measures should be tightly targeted and temporary.

With all that having been said, I’m not so sure that letting the inflation target slip up to 4 percent mightn’t be a worthwhile part of the solution. It might actually be a better target to aim at. After all Martin’s logic below was the logic Churchill used to return to gold after WWI which wan’t a big success (though what he was trying to do there was much more dramatic). Also I feel Martin’s pain concerning the British Government’s credibility. Along with the US, who would trust the British Government’s credibility when, like the US, it remains so vulnerable to the elite vandalism that brought us Brexit?

Something has to change, radically and soon. We are seeing a price-price and wage-price spiral radiating throughout the economy. The only way to halt this is to remove the accommodating demand. In other words, the question is not whether there will be a recession; it is rather whether there needs to be one, if the spiral is to be halted. The plausible view is that the answer to the latter part of this question is “yes”. Like it or not (I certainly do not), the economy will not get back to 2 per cent inflation without a sharp slowdown and higher unemployment.

This raises four questions.

The first is whether current monetary policy is tight enough. The argument that it might be is that borrowers are highly vulnerable to higher nominal interest rates, after a long period of ultra-low rates. Against this, today a 5 per cent nominal rate implies a real rate of less than minus 2 per cent. Moreover, the squeeze will come quite slowly. According to the Financial Conduct Authority, in the second half of 2021, 74 per cent of mortgages were at interest rates fixed for between two and five years. In sum, rates may have to rise again.

The second is whether the government should cushion the blow to borrowers. The answer is: absolutely not. One reason is that people with large mortgages are relatively well off, as Torsten Bell of the Resolution Foundation points out. The right policy is rather targeted assistance for the most vulnerable. Another reason is that this would defeat the object of the exercise, which is to tighten demand. If fiscal policy were to offset this, monetary policy would have to be still tighter than otherwise. If the desire is to moderate the monetary squeeze, fiscal policy should be tightened, not loosened.

The third is whether the uncertainty that surrounds all these decisions should itself encourage extreme caution in tightening. Unfortunately, it is not so simple. True, there exists much uncertainty about the strength of the underlying inflationary pressure and so about how deep an economic slowdown is needed to bring it under control. There exists, similarly, much uncertainty about how much tightening is needed to bring about such a slowdown. But if one is determined to bring inflation back to target in the near future (that is, in less than two years), it is untrue that the smaller mistake would be to err on the side of optimism about how easily inflation will fall. Doing less would reduce the slowdown now. But, if it failed to deliver the needed fall in inflation, a still bigger slowdown might be needed later on, when inflation would be still more entrenched.

The last question is whether it is worth the effort: why not just give up on the target and accept, say, 4 or 5 per cent inflation? The answer is that if a country abandons its solemn promise to stabilise the value of the currency as soon as it becomes hard to deliver, other commitments must also be devalued. At home and abroad, many will conclude that the UK is unable to keep its promises when things get tough. That is what happened, to a significant degree, in the course of the 1970s: the UK started to be a joke. To repeat this, particularly after Brexit, would be an unpardonable — possibly even incurable — folly.

Amazing

For a different view on inflation read Felix Martin’s latest column

The next revolution in monetary policy may be brewing. Start with the IMF. At the European Central Bank’s annual get-together in the Portuguese village of Sintra on Monday, Gita Gopinath, the fund’s deputy managing director, urged policymakers to confront what she called some “uncomfortable truths”. Foremost amongst these is that since central banks began hiking interest rates in late 2021 they have exposed a string of unexpected financial stresses.

Last October, UK markets descended into turmoil as margin calls on leveraged investment strategies caused British pension funds to panic-sell government bonds. A month later a default by a South Korean Legoland theme park developer triggered an economy-wide credit crunch in the Asian country. Jitters caused by higher borrowing costs also contributed to the failures of lenders like SVB Financial and Signature Bank in the United States and Credit Suisse in Europe.

Central banks can relatively easily limit the impact of problems arising in the financial sector. Containing the fallout from rate hikes in other parts of the economy is much more tricky, Gopinath warned.

As if on cue it seems that Thames Water – the UK’s largest water and sewage utility, responsible for supplying nearly a third of the population of England and all of London – is on the brink of insolvency. The root problem is its inability to service 14 billion pounds of debt accumulated during the low-interest rate era. The impact of inflation-fighting rate hikes has quite literally reached the capital’s kitchen sinks.

The rolling cascade of financial accidents has undermined the credibility of policymakers’ hawkish rhetoric. As a result, sizable gaps have regularly opened up between market expectations of future policy rates – as conveyed, for example, by Fed Funds futures in the United States – and central bankers’ own projections. Investors are sceptical that central banks can make good on their inflation-fighting promises.

On Monday, Gopinath urged policymakers to regain the initiative by acknowledging that markets have a point. In a world of gargantuan public and private sector balance sheets, there is indeed a trade-off between controlling inflation and maintaining financial stability.

The implication is that central banks should tolerate above-target inflation in the short term in order to restore price stability in the medium term without causing a financial catastrophe along the way. Though no senior IMF official would ever put it so bluntly, a modest dose of financial repression is the least bad option until the necessary deleveraging has taken place.

Then Felix goes on:

This epic analysis has much deeper policy implications than Gopinath’s proposal to trade higher inflation for more financial stability.

You can read about that by clicking “More Here”.

Humprey Bogart and Lauren Bacall at home

He doesn’t look at all well does he? He died less than three years later buried with the bracelet you see discussed in the clip.

Weekend long read (heavy-ish … but interesting)

“Honour in the oikos: Reciprocity, respect, and recognition in fourth-century Athens”

Abstract of a PhD thesis by Bianca Mazzinghi Gori

I’m afraid I’m a sucker for this kind of thing:

This thesis examines dynamics of honour and respect in families of fourth-century BCE Athens by looking in particular at the subordinate members of Athenian families, namely children, women, and slaves. As this thesis contributes to affirm, the Greek word normally translated as honour, timē, has a much broader meaning than our current notion of honour. Classical Athens was a patriarchal society that heavily relied on slave labour; for this reason, it is often assumed that the subordinate members of the family such as slaves and women had no claims to respect.

By focusing on the subordinate members of Athenian families, the thesis aims to show that the Greek notion of honour was able to accommodate bidirectional honour, recognition, and respect. As we shallsee, this means thatthese dynamics involve simultaneous attention for one’s own standing and for that of others’, as well as a concern with what we think that others think of us. Thanks to the bidirectionality of honour, the subordinate members of the oikos were engaged in complex interpersonal dynamics, within which their claims to recognition are intertwined to those of others.

In the first Chapter, I provide an overview of the expressions that honour dynamics can take in the context of the household. First of all, I show that honour was regarded as an essential aspect of relationships in general: symmetrical and asymmetrical relationships alike were conceptualised in terms of each party’s respective worth and of mutual honour and respect. Moreover, the family is conceptualised as a cooperative enterprise, to which all members contributes according to their specific roles and worth. Therefore, all members deserve recognition in so far as they fulfil their role.

In Chapter 2, I investigate the issue of infants’ honour, addressing the question of whether it is possible that infants have honour at all. I discuss at length Plato’s and Aristotle’s views of infants’ psychology, highlighting the problems in their accounts as well as the potentiality for a recognition of infants’ honour. As modern developmental psychology shows, even infants are involved in honour dynamics: they expect adults to treat them in certain ways and express their upset when they do not receive the proper attentions. I argue that, in spite of Plato’s and Aristotle’s caution, other case studies acknowledge these claims to respect on the part of infants.

Chapter 3 looks at the honour of children first in their relationships with parents, siblings, and friends, and then in their education and socialisation. In the case of relationships with parents, gratitude is the key theme: children were expected to honour their parents and be iii grateful for all the care they received from them. However, parents needed to respect their children: as shown in all the other chapters, asymmetry does not exclude reciprocity. In the case of peers, the main theme is the tension between affection and envy, which depends on the tension between equality and individuality. These relationships were thus a good arena for children to learn how to balance self-assertion with respect for others. In their education and socialisation, honour can be seen as both instrument and content: children’s desire to be recognised and to emulate role models is harnessed by parents and teachers to teach them what is honourable and dishonourable. Mechanisms of honour and recognition are also harnessed in the polis to socialise children to their social roles.

Chapter 4 is devoted to women’s honour. I start by stressing the utmost importance of reciprocity and cooperation in conceptualisations of marriage, which was also based on a division of entitlements and prerogatives: wives had their own sphere of influence in the household, and husbands were expected to respect their authority. The ideal husband-wife relationship was based on mutual love and esteem. When things went wrong, some leniency was regarded as praiseworthy; extra-marital sex was not seen a priori as tainting the wife’s purity, but attention was paid to the wife’s intentions. Although their claims could easily be ignored, even lovers and pallakai could lay claims to respect on the basis of their love and relationship with a man. In addition to their relationships with men, women could attain recognition and pride also through paths such as their work or involvement in religious activities. Thus, the honour of women appears very complex and nuanced, and women appear capable of exploiting honour dynamics to defend and increase their status.

In Chapter 5 I consider slaves. As I show, even master-slave relationships can accommodate reciprocity and mutual expectations, although reciprocity was sometimes exploited as an instrument of slave management on the part of masters. Regardless of the quality of their relationship with masters, however, our case studies show that slaves had a distinct sense of dignity and of their entitlements to fair treatment. Moreover, they could shape their identity and self-esteem beyond their legal status, for instance by identifying with their ethnic group or stressing their professional expertise.

Overall, the thesis shows that honour dynamics in ancient Athens were often cooperative and inclusive rather than competitive and exclusive; thanks to its flexibility and bidirectionality, moreover, the Greek notion of honour could empower the subordinate members of the iv household, enabling them to negotiate their claims and develop their sense of self-worth and self-esteem.

So many good things - long essays, videos, discussions - history and the present - John Cleese. Thanks.