Being a culture warrior means never having to say you’re sorry

And other fine offerings for the week

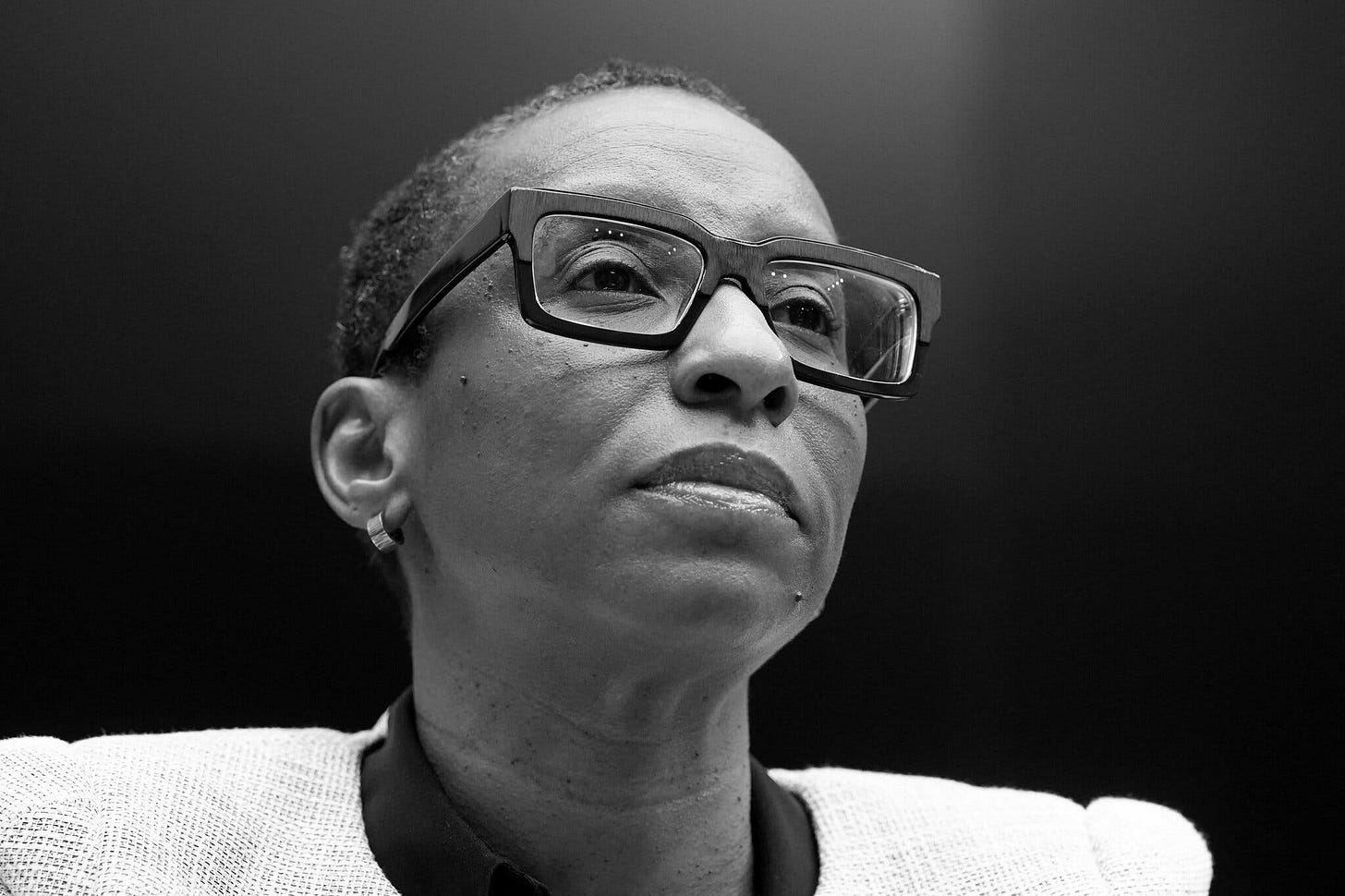

Claudine Gay gets the chop

A fine piece from black academic, wonderfully entertaining linguist and anti-woke warrior John McWhorter. He didn’t pile on with the sting on Claudine Gay, but as the evidence mounted that the only thing would keep her in her job was an unmistakably heavy dose of hypocrisy, he decided enough was enough:

Harvard has a clear policy on plagiarism that threatens undergraduates with punishment up to the university’s equivalent of expulsion for just a single instance of it. … Dr. Gay [s]taying on would not only be a terrible sign of hollowed-out leadership, but also risks conveying the impression of a double standard at a progressive institution for a Black woman, which serves no one well, least of all Dr. Gay. …

[T]here are two problems here. One is Harvard’s plagiarism policy for students, its veritas image and other standards of integrity and conduct. Second is the sheer amount of the plagiarism in her case, even if in itself it is something less than stealing ideas. If the issue were a couple of hastily quoted phrases in one article, it would be one thing. But investigations have shown that this problem runs through about half of Dr. Gay’s articles, as well as her dissertation. …

That Dr. Gay is Black gives this an especially bad look. If she stays in her job, the optics will be that a middling publication record and chronically lackadaisical attention to crediting sources is somehow OK for a university president if she is Black. This implication will be based on a fact sad but impossible to ignore: that it is difficult to identify a white university president with a similar background. Are we to let pass a tacit idea that for Black scholars and administrators, the symbolism of our Blackness, our “diverseness,” is what matters most about us? I am unclear where the Black pride (or antiracism) is in this.

After the congressional hearing this month where Dr. Gay made comments about genocide and antisemitism that she later apologized for, and now in the aftermath of the plagiarism allegations, some of her supporters and others have argued that the university should not dismiss Dr. Gay, because doing so would be to give in to a “mob.” However, one person’s mob is another person’s gradually emerging consensus among reasonable people.

I, for one, wield no pitchfork on this. I did not call for Dr. Gay’s dismissal in the wake of her performance at the antisemitism hearings in Washington, and on social media I advised at first to ease up our judgment about the initial plagiarism accusations. But in the wake of reports of additional acts of plagiarism and Harvard’s saying that she will make further corrections to past writing, the weight of the charges has taken me from “wait and see” to “that’s it.”

If it is mobbish to call on Black figures of influence to be held to the standards that others are held to, then we have arrived at a rather mysterious version of antiracism, and just in time for the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday in less than a month. I would even wish Harvard well in searching for another Black woman to serve as president if that is an imperative. But at this point that Black woman cannot, with any grace, be Claudine Gay.

Being a culture warrior means never having to say you’re sorry

Here’s Tyler Austin Harper explaining why you might want to defend academic standards even when it’s a right wing culture warrior who’s orchestrated the sting and targeted someone as a DEI hire. Here’s a useful summary of Gray’s plagiarism. It’s far from the worst case around but let’s just say it’s, ehem, “systemic”.

The conservative activist Christopher Rufo, who helped kick off this controversy when he and fellow conservative Christopher Brunet leveled a round of accusations against Gay last month, has spent the past 24 hours doing a victory lap. It is this unseemly context that many academics are hung up on: In their minds, a college president succumbed to conservative pressure. And this fact is melting their brains and obliterating their standards for professional conduct. As Harvard Law’s own Charles Fried told The New York Times, “It’s part of this extreme right-wing attack on elite institutions.” And: “If it came from some other quarter, I might be granting it some credence … But not from these people.” Although the donor revolt and conservative pressure campaigns on elite universities—and, more important, public universities—are deeply worrying, the response of some faculty members to this plagiarism scandal is bound to make things worse.

The true scandal of the Claudine Gay affair is not a Harvard president and her plagiarism. The true scandal is that so many journalists and academics were willing, are still willing, to redefine plagiarism to suit their politics. Gay’s boosters have consistently resorted to Orwellian doublespeak—“duplicative language” and academic “sloppiness” and “technical attribution issues”—in a desperate effort to insist that lifting entire paragraphs of another scholar’s work, nearly word for word, without quotation or citation, isn’t plagiarism. Or that if it is plagiarism, it’s merely a technicality. Or that we all do it. (Soon after Rufo and Brunet made their initial accusations last month, Gay issued a statement saying, “I stand by the integrity of my scholarship.” She did not address those or subsequent plagiarism allegations in her resignation letter.)

Rufo won this round of the academic culture war because he exposed so many progressive scholars and journalists to be hypocrites and political actors who were willing to throw their ideals overboard. I suspect that, not the tenure of a Harvard president, was the prize he sought all along. The tragedy is that we didn’t have to give it to him. …

And it’s clear, too, that her violations pale in comparison to some other real and rumored instances of plagiarism in elite higher education. Still, the linguistic gymnastics in her defense are shameful. Indeed, the historian David A. Bell wrote that the language games some progressives are currently playing are positively Trumpian. “What bothers me most about this whole affair is the fact that Gay herself has not taken responsibility for the plagiarism,” Bell said, “and that so many have supported her in not doing so.” A Harvard alum who’s an academic acquaintance of mine offered a similar summary: “Sitting here watching people I respect say ‘We all do this all the time; nothing to see here’ actually hurts me a bit. I feel gaslighted, in the parlance of our time.”

When the plagiarism scandal ramped up just a few days after the congressional hearing, it felt pretextual because it was. Rufo and Brunet’s first allegations were wheeled out on December 10, and Rufo was transparent about their intentions: “We launched the Claudine Gay plagiarism story from the Right,” he wrote on social media. “The next step is to smuggle it into the media apparatus of the Left, legitimizing the narrative to center-left actors who have the power to topple her. Then squeeze.” …

Those who rushed to characterize her resignation as the outcome of a “bullying” campaign designed to oust Harvard’s first Black president omit an inconvenient detail: She was clearly guilty. The bullying worked because the facts were too difficult to massage. That didn’t stop many of my fellow academics from trying. …

“I want to support Claudine,” said [Stephen Voss, one of the scholars whose work Gray had plagiarised], “but I cannot respect anyone who, in pursuit of political goals, would pretend that students are allowed to do what Gay did. Changing principles to suit the controversy du jour occurs too often on both sides of the political divide.”

Voss is entirely correct. Using watery euphemisms to refer to blatant plagiarism debases our profession, and the assertion that everyone plagiarizes if you just look hard enough debases it further. The media are currently distracted by the shiny bauble of Harvard’s ousted president, but we should be far more concerned about the crisis of academic culture that this incident has exposed. For all the talk of “glass ceilings,” Gay is a Cambridge woman through and through: Born to a family that runs a Haitian concrete empire, she was shot out of America’s most prestigious boarding school before being educated at Princeton, Stanford, and Harvard. As the first Black woman to lead America’s most prestigious university, Gay may have changed the color of the mold, but she sure didn’t break it.

The idea that clear and long-established criteria for plagiarism should have been thrown out to save the elite-born president of an elite university, solely on the basis of her skin color, is not only preposterous; it’s that old soft bigotry. There are talented senior academics and administrators of color across this country who don’t need anyone to lower plagiarism standards for them. Harvard can, and should, hire one of them. Doing so would put a thumb in the eye of the meddling right, defending the ideal of diversity while sending a clear message that neither conservative media nor billionaire alumni get to decide who runs the university.

War is hell: don’t go

Ukraine edition

This piece offers a good looking back and forward of the terrible situation in Ukraine putting me in mind of this quote from Hannah Arendt on the publication of the Pentagon Papers.

The divergence between the facts established by the intelligence services — sometimes by the decision makers themselves (as notably in the case of McNamara) and often available to the informed public — and the premises, theories, and hypotheses according to which decisions were finally made is total. And the extent of our failures and disasters throughout these years can be grasped only if one has the totality of this divergence firmly in mind.

It’s about the importance of not being seduced by your own propaganda — something that’s hard for us all, even more difficult for groups of people and pretty impossible for nations it seems, particularly in war.

The way the American media has dealt with the Ukraine War brings to mind a remark credited to Mark Twain: “The researches of many commentators have already thrown much darkness on this subject, and it is probable that, if they continue, we shall soon know nothing at all about it.”

It is a more verbose expression of a better-known maxim: in war, truth is the first casualty. It is typically accompanied by a fog of official lies. And no such fog has ever been as thick as in the Ukraine war. While many hundreds of thousands of people have fought and died in Ukraine, the propaganda machines in Brussels, Kyiv, London, Moscow and Washington have worked overtime to ensure that we take passionate sides, believe what we want to believe, and condemn anyone who questions the narrative we have internalised. The consequences for all have been dire. For Ukraine, they have been catastrophic. As we enter a new year, a radical rethinking of policy by all concerned is long overdue.

This is a consequence of the fact that the war was born in and has been continued due to miscalculations by all sides. The United States calculated that Russian threats to go to war over Ukrainian neutrality were bluffs that might be deterred by outlining and denigrating Russian plans. Russia assumed that the United States would prefer negotiations to war and would wish to avoid the redivision of Europe into hostile blocs. Ukrainians counted on the West protecting their country. When Russia’s performance in the first months of the war proved lacklustre, the West concluded that Ukraine could defeat it. None of these calculations has proved correct.

Nevertheless, official propaganda, amplified by subservient mainstream and social media, has convinced most in the West that rejecting a draft peace treaty before the invasion and encouraging Ukraine to fight Russia is somehow “pro-Ukrainian”. Sympathy for the Ukrainian war effort is entirely understandable, but, as the Vietnam War should have taught us, democracies lose when cheerleading replaces objectivity in reporting and governments prefer their own propaganda to the truth of what is happening on the battleground. So, what is happening on the battleground? And how are the participants in the Ukraine War doing in terms of achieving their objectives? …

Let’s start with Ukraine. From 2014 to 2022, the civil war in the Donbas took nearly 15,000 lives. How many have been killed in action since the US/Nato-Russian proxy war began in February 2022 is unknown, but is certainly in the several hundreds of thousands. Casualty numbers have been concealed by unprecedentedly intense information warfare. The only information in the West about the dead and wounded has been propaganda from Kyiv claiming vast numbers of Russian dead while revealing little about Ukrainian casualties. Yet even by last summer, it was known that 10% of Ukrainians were involved with the armed forces, while 78% had relatives or friends who had been killed or wounded. It is estimated that between 20,000 and 50,000 Ukrainians are now amputees. (For context, 41,000 Britons had to have amputations in the First World War, when the procedure was often the only one available to prevent death. Fewer than 2,000 US veterans of the Afghanistan and Iraq invasions had amputations.) …

However, neither has Russia, as per its war objectives, succeeded in expelling American influence from Ukraine, forced Kyiv to declare neutrality, or reinstated the rights of Russian speakers in Ukraine. Indeed, whatever the outcome of the war, mutual animosity has erased the Russian myth of Russian-Ukrainian brotherhood based on a common origin in Kyivan Rus. Russia has had to abandon three centuries of efforts to identify with Europe and instead pivot to China, India, the Islamic world and Africa. Reconciliation with a seriously alienated European Union will not come easily, if at all. Russia may not have lost on the battlefield or been weakened or strategically isolated, but it has incurred huge opportunity costs.

But even if the war has disadvantaged Russia, it’s far from clear that it has benefited the United States. … To weaken Russia, the United States has been actively blocking trade between countries that have nothing to do with Ukraine or the war there because they won’t jump on the US bandwagon. This use of political and economic pressure to compel other countries to conform to its anti-Russian and anti-Chinese policies has clearly backfired. It has encouraged even former US client states to search for ways to avoid entanglement in future American conflicts and proxy wars they do not support, like that in Ukraine. Far from isolating Russia or China, America’s coercive diplomacy has helped both Moscow and Beijing to enhance relationships in Africa, Asia, and Latin America that reduce US influence in favour of their own. …

Unfortunately, as things stand, both Moscow and Washington seem determined to persist in Ukraine’s ongoing destruction. But whatever the outcome of the war, Kyiv and Moscow will eventually have to find a basis for coexistence. Washington needs to support Kyiv in challenging Russia to recognise both the wisdom and the necessity of respect for Ukrainian neutrality and territorial integrity.

Finally, this war should provoke some sober rethinking in both Washington and Moscow about the consequences of diplomacy-free, militarised foreign policy. Had the United States agreed to talk with Moscow, even if it had continued to reject much of what Moscow demanded, Russia would not have invaded Ukraine as it did. Had the West not intervened to prevent Ukraine from ratifying the treaty others helped it agree with Russia at the outset of the war, Ukraine would now be intact and at peace. This war did not need to take place. And every party to it has lost far more than it has gained.

Oh — and since I quoted Hannah Arendt, at the beginning of the ‘70s, here’s Alexander Solzhenitsyn from the end of them. (HT: Henry Ergas’s recent column).

Without any censorship in the West, fashionable trends of thought and ideas are fastidiously separated from those that are not fashionable, and the latter, without ever being forbidden have little chance of finding their way into periodicals or books or being heard in colleges. Your scholars are free in the legal sense, but they are hemmed in by the idols of the prevailing fad. There is no open violence, as in the East; however, a selection dictated by fashion and the need to accommodate mass standards frequently prevents the most independent-minded persons from contributing to public life and gives rise to dangerous herd instincts that block dangerous herd development.

Robert Mapplethorpe’s flowers

I’ve just finished listening to Patti Smith’s memoir of her lover Robert Mapplethorpe Just Kids. It is very moving. I didn’t know Mapplethorpe had a series of flower photographs — but I do now. So do you.

Roberto Matta: Senza titolo

Lovely painting. Roberto Matta (1911-2002) - Senza titolo. Yours for around AU $250,000

Tim Colebatch on Singapore

A long informative review of four books on Singapore from Tim Colebatch.

Jeevan Vasagar, a British journalist of Sri Lankan Tamil ancestry, was the Financial Times correspondent in Singapore, and his Lion City: Singapore and the Invention of Modern Asia is an excellent introduction to today’s Singapore. Chua Mui Hoong, a columnist for Singapore’s main paper, the Straits Times, is a wary social critic whose Singapore, Disrupted brings together some of her favourite columns. And Cherian George, once her colleague, has recently published a collection of more substantial essays as Air-conditioned Nation Revisited. (Lee Kuan Yew once famously said that the air conditioner was the greatest twentieth-century invention because it allowed people in the tropics to keep working rather than fall asleep in the heat.)

Within Singapore’s establishment, legal academic and diplomat Tommy Koh is a prominent figure at the liberal reformist end of the spectrum. In editing Fifty Secrets of Singapore’s Success, he celebrates things Singapore has done well: from monetary policy to its national airline, fighting corruption, the Singaporean maths system, parks, public toilets, Changi airport… There’s a long list, all worthy, even if some chapters are superficial.

Singapore has a lot to celebrate. It also has a lot that needs changing. Its rulers have a great appetite for celebrations, but very little appetite for political reform. …

Take the economy first. … Comparisons of household consumption per head, though imperfect, are a better measure of real living standards [than GDP per capita]. On the World Bank’s measure, Singapore in 2020 enjoyed the seventh-highest consumption of goods and services per head of any country, in real terms, behind the United States (first) and just ahead of Australia (ninth). …

The title of an old book on how Singapore did it, Strategic Pragmatism, sums it up well. Rather than follow the precepts of eighteenth-century economic liberalism, Singapore has carved out its own way, testing what works and designing its own solutions. Taxes are low, but as Vasagar puts it, whereas in Hong Kong the tycoons used to dictate to the government, “it is the government that is supreme in Singapore.” …

Every institution with power in Singapore is effectively an arm of the government. There is no free press: the media is either government-owned or controlled by the government’s right to appoint its boards, and the opposition has little access to it. There is no independent judiciary; no minister has ever lost a defamation case in Singapore’s courts. There are no trade unions independent of government. The relatively few NGOs must operate warily to avoid incurring the wrath of the ministers and officials whose decisions they comment on.

There is no right of assembly: to hold a meeting of five or more people requires a permit from the police. There is no ombudsman, no charter of human rights, no freedom of information legislation. Singapore has world-class engineering infrastructure, but little of the infrastructure of democracy as we know it.

It does have free elections. But even they are held on boundaries drawn up by the government to maximise its chances. …

Then again, there’s this amazing factoid. “The overall fertility rate of 1.10 is barely half the rate needed for zero population growth.” Australia’s is 1.58.

Demand and supply of ADHD diagnoses and treatment

Great review of a great book on Free Will

Many scientists of consciousness concluding that free will is an illusion. After all, whether the world is completely deterministic or whether quantum effects add layers of randomisation, surely my fingers are tapping out this sentence because the relevant atoms in my brain somehow happen to be arranging themselves in the right way to get the sentence out. Trouble is, our intuition is begging for something less fanciful. We experience making decisions every hour of the day, and those decisions don’t feel like the product of pure randomness. Well they’re not and a new book tries to explain why. Here’s James Gleick’s review of it.

For physicists, the problem is that we are made of matter, like every particle and planet in the universe, and matter is governed by physical laws. According to the physicist and best-selling author Brian Greene, “We need to recognize that although the sensation of free will is real, the capacity to exert free will—the capacity for the human mind to transcend the laws that control physical progression—is not.” We do not and cannot cause anything; we are caused. “Our choices are the result of our particles coursing one way or another through our brains,” he writes.

Our actions are the result of our particles moving this way or that through our bodies. And all particle motion—whether in a brain, a body, or a baseball—is controlled by physics and so is fully dictated by mathematical decree.

It is a stern and final lesson: “We are no more than playthings knocked to and fro by the dispassionate rules of the cosmos.” Nothing to see here. Move along. …

Kevin J. Mitchell answers exactly this challenge in Free Agents: How Evolution Gave Us Free Will.

Yes, he says, free will exists. It is neither an illusion nor merely a figure of speech. It is our essential, defining quality and as such demands explanation. “We make decisions, we choose, we act,” he declares.

These are the fundamental truths of our existence and absolutely the most basic phenomenology of our lives. If science seems to be suggesting otherwise, the correct response is not to throw our hands up and say, “Well, I guess everything we thought about our own existence is a laughable delusion.” It is to accept instead that there is a deep mystery to be solved and to realize that we may need to question the philosophical bedrock of our scientific approach if we are to reconcile the clear existence of choice with the apparent determinism of the physical universe.

Agency distinguishes even bacteria from the otherwise lifeless universe. Living things are “imbued with purpose and able to act on their own terms,” Mitchell says. He makes a powerful case that the history of life, in all its complex grandeur, cannot be appreciated until we understand the evolution of agency—and then, in creatures of sufficient complexity, the evolution of conscious free will.

Mitchell is one of a new breed of biologists who espouse a complex-systems perspective as an antidote to reductionism. … “The organism is not a pattern of stuff,” Mitchell says; “it is a pattern of interacting processes, and the self is that pattern persisting.” …

Within even a single-celled organism, proteins in the cell wall respond chemically to changing conditions outside and thus act as sensors. Inside, proteins are activated and deactivated by biochemical reactions, and the organism effectively reconfigures its own metabolic pathways in order to survive. Those pathways can act as logic gates in a computer: if the conditions are X, then do A.

“They’re not thinking about it, of course,” Mitchell says, “but that is the effect, and it’s built right into the design of the molecule.” As organisms grow more complex, so do these logical pathways. They create feedback mechanisms, positive and negative. They make molecular clocks, responding to and then mimicking the solar cycle. Increasingly, they embody knowledge of the world in which they live.

We begin to see organisms extracting information from their environment, acting on it in the present, and reproducing it for the future. “Information thus has causal power in the system,” Mitchell says, “and gives the agent causal power in the world.”

We can begin to talk about purpose*.* First of all, organisms struggle to maintain themselves. They strive to persist and then to reproduce. Natural selection ensures it. “The universe doesn’t have purpose, but life does,” Mitchell says.

And unlike the designed machines and gadgets that surround us in our daily lives, which also have a purpose or at least serve a purpose, living organisms are adapted for the sake of only one thing—their selves. This brings something new to the universe: a frame of reference, a subject. The existence of a goal imbues things with properties that previously never existed relative to that goal: function, meaning, and value.

Free will: the podcast

I was even more impressed when I listened to this podcast, and particularly at the Mitchell’s naturalistic, and commonsensical explanation of the way purpose, value, and meaning emerge in evolution. The key idea is that biology is a matter of energetics and information rather than mechanics.

Michael Polanyi on the ascent of life

Michael Polanyi was taking aim at exactly the same fundamentalist materialist reductionism from around eighty years ago. Here he is in the 1960s explaining his alternative — emergentism. I think it makes obvious sense.

A machine or a machine like functioning living being can be said … to comprise two levels. There is an upper, comprehensive level embodying the operational principles of the system and a lower, more primitive level, controlled by the laws of physics and chemistry. The lower level is formed by the unorganized mass, the higher level by the principle that controls its organization. In other words, we have a lower level of isolated parts and a higher level of the functional whole formed by the parts. This higher level represents then the joint "meaning" of the parts. We see here the beginnings of a hierarchy in which the distinction between things essentially higher and essentially lower is restored.

We can generalize the two-level structure of living beings and machines to the playing of a game of chess. The conduct of such a game is an entity controlled by a stratagem and the stratagem relies on the observance of the rules of chess. This relation does not hold in reverse, for the rules of chess leave open an infinite range of stratagems. Chess moves are therefore meaningless by themselves; their meaning lies in serving jointly the performance of a stratagem.

SEQUENCE OF LEVELS

All these relations become clearer in the case of a skill which comprises a number of levels in the form of a hierarchy. The pro- duction of a literary composition, for example a speech, includes five levels. The first level, lowest of all, is the production of a voice; the second, the utterance of words; the third, the joining of words to make sentences, the fourth, the working of sentences into a style; the fifth, and highest, the composition of the text. The principles of each level operate under the control of the next higher level. The voice you produce is shaped into words by a vocabulary; a given vocabulary is shaped into sentences in accordance with a grammar; and the sentences are fitted into a style, which in its turn is made to convey the ideas of the composition. Thus each level is subject to dual control; first, by the laws that apply to its elements in themselves, and second, by the laws that control the comprehensive entity formed by them.

Such multiple control is made possible again by the fact that the principles governing the isolated particulars of a lower level leave indeterminate their boundary condition, to be controlled by a higher principle. Voice production leaves Largely open the combination of sounds into words, which is controlled by a vocabulary. Next, a vocabulary leaves largely open the combination of words to form sentences, which is controlled by grammar; and so the sequence goes on. Consequently, the operations of a higher level cannot be accounted for by the laws governing its particulars forming the next lower level. You cannot derive a vocabulary from phonetics, you cannot derive grammar from a vocabulary; a correct use of mammas does not account for good style; and a good style does not supply the content of a piece of prose. A glance at the functions of living beings assures us that they consist in a whole sequence of levels forming such a hierarchy. The lowest level is controlled by the laws of inanimate nature and the higher levels control throughout the boundary conditions left open by the laws of the inanimate. The lowest functions of life are those called vegetative; these vegetative functions, sustaining life at its lowest level, leave open—in both plants and animals—the higher functions of growth, and leave open in animals also the operations of muscular action: next in turn, the principles governing muscular action in animals leave open the integration of such action to innate patterns of behavior; and again such patterns are open in their turn to be shaped by intelligence; while the working of intelligence itself can be made to serve in man the still higher principles of a responsible choice.

We have thus a sequence of rising levels, each higher one controlling the boundaries of the one below it and embodying thereby the joint meaning of the particulars situated on the lower level. The meaning of each successive rising level thus becomes richer at each stage and reaches the fullest measure of meaning at the top. We can see then why the Universal Knowledge of Laplace, or a physicochemical topography of the world, is virtually meaningless. All meaning lies in higher levels of reality that are not reducible to the laws by which the ultimate particulars of the universe are controlled

The world view of Galileo, accepted since the Copernican revolution proves to be fundamentally misleading. What is most tangible has the least meaning and it is perverse then to identify the tangible with the real. For to regard a meaningless substratum as the ultimate reality of all things must lead to the conclusion that all things are meaningless. And we can avoid this conclusion only if we acknowledge instead that deepest reality is possessed by higher things that are least tangible. …

We need a theory of knowledge which shows up the fallacy of a positivist skepticism and authorizes our knowledge of entities governed by higher principles. Any higher principle can be known only by dwelling in the particulars governed by it. Any attempt to observe a higher level of existence by a scrutiny of its several particulars must fail. We shall remain blind in theory to all that truly matters in the world so long as we do not accept indwelling as a legitimate form of knowledge.

Indwelling involves a tacit reliance on our awareness of particulars not under observation, many of them unspecifiable. We have to interiorize these and, in doing so. must change our mental existence. There is nothing definite to which we can hold fast in such an act. It is a free commitment. But there is something imponderable for us to rely on. We have around us great truths embodied in works born of the very freedom which we are hesitating to enter. And recent history has taught that we can breathe only in the ambience of these truths and of this creative freedom. I, for one, am prepared to rely on this assurance for acquiring and upholding knowledge by embracing the world and dwelling in it.

From: “On the modern mind” first published in Encounter, 15th May, 1965.

Sigmund Freud’s psychobiography of Woodrow Wilson

An interesting review of a new book on a psychobiography of Woodrow Wilson who was, among other things, a very nasty racist — as in worse than your average American in the early 20th century and, to paraphrase Groucho, that’s not saying much for him. But I digress. If only he’d been able to pull off his great cause to make WWI the war that ended war — or at least not have it as the proximate cause for WWII. Anyway, the review kicks off with a fine vignette about Freud’s psychobiography of Leonardo. Oops.

Sigmund Freud’s first venture into biographical writing is a cautionary tale for anyone tempted to apply psychoanalytic ideas to historical figures. His essay on Leonardo da Vinci, first published in 1910, fixed on a memory Leonardo reported from his early childhood of a vulture descending on his cradle and repeatedly thrusting its tail in his mouth. Freud surmised that this “memory” was in fact a fantasy that revealed Leonardo’s homosexuality and his conflicted feelings about his mother.

Freud’s interpretation hinged on the mythology of vultures — including the ancient belief that they were exclusively female and impregnated by the wind — and the frequent depiction of the Egyptian goddess Mut with a vulture’s head and an androgynous body. He argued that Leonardo was preoccupied with vultures and had concealed one in the blue drapery of The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, which hangs in the Louvre.

There was one small problem. The bird Leonardo recalled was not a vulture but a kite, a creature with no special mythic significance or any hint of sexual ambiguity. The error, made by a German translator of Leonardo’s writings, undermined Freud’s thesis and demonstrated the challenges of doing psychoanalytic interpretation at a distance. When the subject cannot be put on the couch, the already dangerous work of psychic excavation becomes even more hazardous. …

Psychobiography is often viewed — and sometimes practised — as an exercise in armchair speculation and hatchet work unencumbered by evidence, but the dissection of Wilson’s character was anything but. Freud, perhaps stung by the Leonardo fiasco, insisted on collecting and analysing a substantial body of information on Wilson; Bullitt obliged with not only his extensive first-hand working experience but also interviews with several of Wilson’s high-ranking colleagues, hundreds of pages of notes, and countless diary entries from Wilson’s personal secretary. Then, at least on Bullitt’s telling, he and Freud met and communicated frequently over a period of years to formulate a shared understanding of Wilson’s psychodynamics and edit drafts of one another’s chapters.

The essence of their formulation was that Wilson lived in the shadow of his idealised father, a Christian minister, whom he believed he could never satisfy or equal. This father complex was shown in his driven approach to work, his tendency to present a Christ-like persona when defending his views, his moralising streak, his unwillingness to brook criticism or compromise when he took principled stands on issues, and his passivity towards paternal figures — a stance that led to bitter fallings-out with erstwhile good friends that haunted him for decades.

Bullitt and Freud attributed Wilson’s failures in delivering on Versailles and the League of Nations to this incapacity to make necessary accommodations at the last hurdle. They also drew attention to his tendency to defer to some national leaders during the earlier negotiations to the detriment of the treaty, including allowing Britain to make the excessive demands for postwar reparations that contributed to German resentment.

After extensive reworking over a period of years, the Wilson manuscript was completed in 1932, each chapter signed off by both authors. And yet it was not to be published until 1967. The reasons for the delay initially included Bullitt’s desire not to endanger his employment prospects in future Democratic administrations, a wish not to hurt Wilson’s widow, and an awareness that Wilson’s once tarnished reputation had been restored by mid-century, making a critical study unwelcome. Later, in the 1960s, Bullitt found it difficult to find a publisher and to obtain permission to publish from Freud’s estate. Freud’s daughter Anna, whom Bullitt had helped to rescue from Vienna in 1939, was deeply concerned to protect her father’s legacy and sceptical of Freud’s involvement in the book; she insisted on making numerous revisions, which Bullitt refused.

Another animal video

I don't know why this algorithm keeps coming after me (well I do actually, I kept clicking on cute animal videos), but this is HILARIOUS!

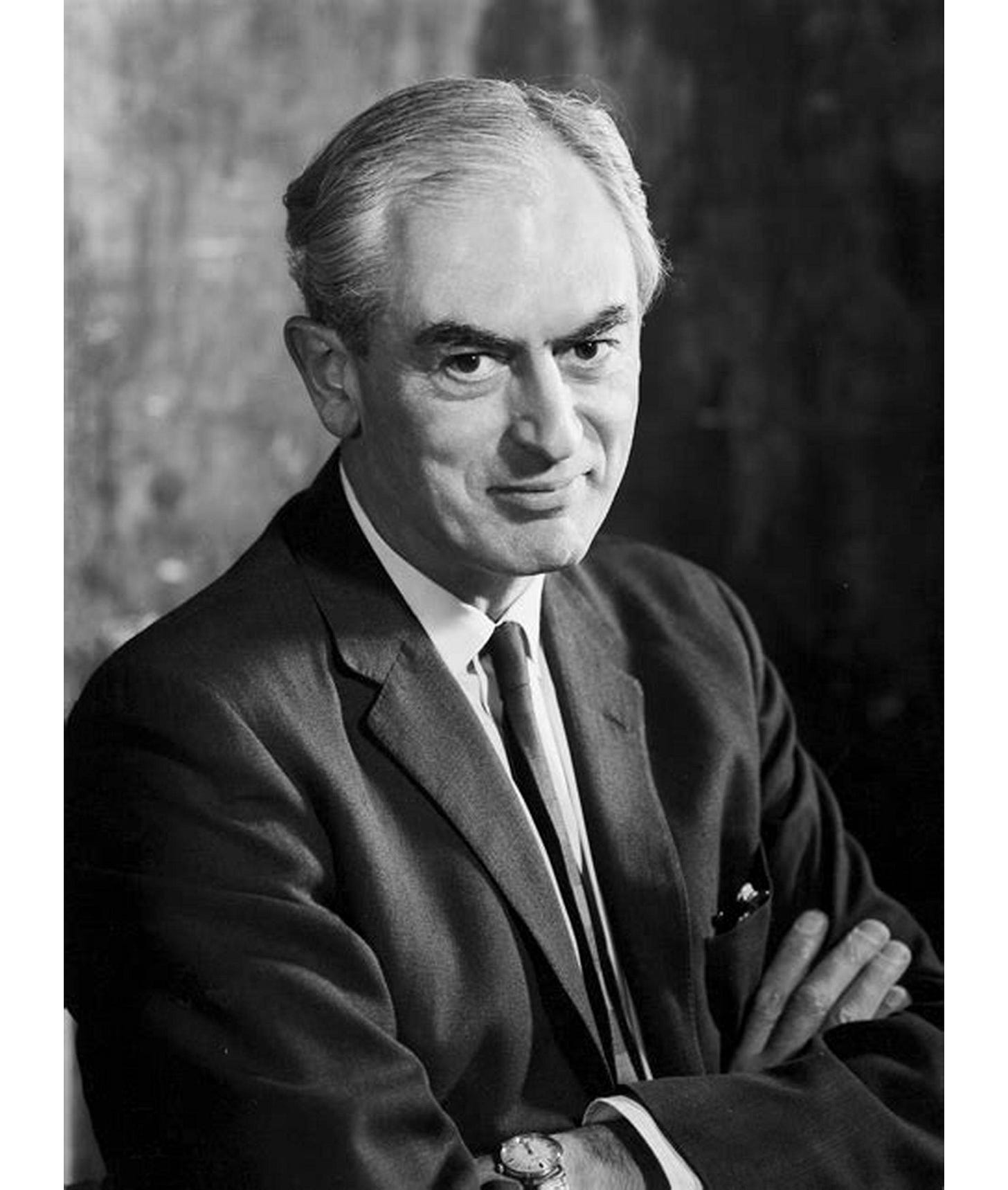

Michael Polanyi in 1960 on Teilhard de Chardin on evolution

Michael Polanyi was highly suspicious of the hyper-reductionism of neo-Darwinism. It’s reduction of the evolution of a thing so vast as life into a single causal mechanism. And it was a good call.

Darwin himself had proposed that natural selection was a major mechanism of evolution, but not the only one. He was good with the existence of Lamarckian mechanisms, which was a pretty good call given that they keep turning up. But neo-Darwinism held that there was just one mechanism behind evolution — genetic variation — and that this was driven exclusively by random mutation. It’s worth pondering the hankering for closure this claim embodies. Why the enthusiasm to claim a single cause?

Neatness is one reason. Arrogance another. Laying down the law on the grounds that you’re uniquely qualified to pontificate about them is inherently satisfying to many. There’s also a doubling down on driving purpose out of evolution. And that’s something science had been doing since the scientific revolution — driving our Aristotelian notions of telos from biology. And that was also driving God out of biology. All good if God is seen as some imposition — some being intervening in the universe whenever he wants to vote someone off the island.

The thing is, immanent purpose is an obvious fact of biology. The heart has the purpose of pumping blood. It’s designed to pump blood. That doesn’t mean it has an intelligent designer watching on, occasionally reaching for their remote. But it does mean that it was designed. It was designed immanently. We've known for a long time that the immune system works this way — it creates a randomising process of experimentation and then puts its thumb on the scales by amplifying the more promising experiments.

In any event the idea of systems of "directed chance" and the ‘emergentism’ that naturally arises from it fascinated Polanyi and lay as one of the core elements of his philosophy of science and of humanity.

Which meant that I was fascinated and impressed by this brief review. At the time he wrote it Teilhard de Chardin was speaking to these ideas. But Polanyi is suspicious and put his concerns very well I think.

An Epic Theory of Evolution

THE SUCCESS of "The Phenomenon of Man," by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin is a mystery and a portent. … I have seen a dozen reviews highly praising it and have noticed no adverse criticism. I, myself, had readily turned to Teilhard, since I reject the current genetical theory of evolution and had no doubt that Teilhard rejects it too.

But what about all those who so eagerly read and praise the book? Does their acclaim mark the rise of a vast underground movement, sweeping aside the writers and readers who had shortly before accepted the worldwide pronouncements made on the occasion of the Darwin centenary? Where was the public now applauding Teilhard when Sir Gavin de Beer declared that modern genetical research has "established as firmly as Newton's laws of motion that hereditary resemblances are determined by discreet particles, the genes, situated in the chromosomes of the cells. . . "? Can this be reconciled with Teilhard's teachings?

Puzzled by these questions, I kept fingering my copy of Teilhard's English' translation and finally looked through Julian Huxley's introduction. In it he praises Teilhard's work highly and, indeed, claims to have largely anticipated it. Yet it was Sir Julian' Hpdey who prefaced one of thentost authoritative statements of current selectionist theory ("Evolution as a process") with the words: "A single basic mechanism underlies the whale organic evolution—Darwinian selection acting upon the genetic. mechanism."

Teilhard declares: "We do not yet know how characters are formed, acumulated and transmitted in the secret recesses of the germ cell." In his view, "the blind determinism of the genes" plays but a subordinate part: "We are dealing with only one event," he says, "the grand orthogenesis of everything living towards a higher degree of immanent spontaneity." "The progressive leaps of life" must be interpreted "in an active and finalistic way."

A text that is so ambiguous that people whose views on its subject matter are diametrically opposed can read it with equal enthusiasm cannot be wholly satisfying.

This active striving towards ever higher, more vividly conscious forms of existence, which eventually achieves responsible human personhood and establishes through man a realm of impersonal thought, is the dominant theme of "The Phenomenon of. Man." . . 'This image is.very different from that of the repeated failures of precision in the self-copying of Mendelian genes, to which Huxley and the rulihg orthodoxy attribute evolution. It is precisely the kind of theory violently condemned by this orthodoxy for trying to explain evolution by some inherent bias, guiding the direction mutations take. Admittedly, Teilhard's wording is vague.…

Teilhard's way r of shrugging aside any question concerning the mechanism of heredity also casts a veil of obscurity tn the foundations of his position. And this is how he avoids an explicit attack on genetical selectionism and also feels entitled to use, without more than the most cursory acknowledgment, the ideas of Samuel Butler, Bergson, and others who have previously interpreted evolution in his way.

And yet in these shortcomings we discover the secret of Teilhard's achievement and success. He is a naturalist and a poet, endowed with contemplative genius. He refuses to look upon evolution like a detached observer who reduces experience to the exemplification of a theory. Instead he stages a dramatic action of which 'man is both a product and a responsible participant. His purpose is to rewrite the Book of Genesis in terms of evolution. The thousand million years of evolution are seen here as one single act of cre-ative power, like that revealed by Genesis.

This creative act is inherent in the universe. By producing sentient beings the universe illuminates itself, and through human thought it gradually achieves communion with God. Teilhard uses scientific knowledge merely as a factual imager* in which to expound his vision. His work is an epic poem that keeps closely to the facts. Gaps in the factual imagery of a poem can be safely left- open. So there is no need for the author to argue with selectionism.

As a poet, Teilhard stands powerfully apart and commands assent from many who continue to hold views that are incompatible with his vision; and this is how his work is startlingly novel though it contains few new ideas. . But would Teilhard's poetry have received such warm response fifty years ago? No, its contemporary success, is a portent. There is a tide of dissatisfaction mounting up against scientific obscurantism. Book after book comes out aiming against the scientific denaturation of some human subject.

Teilhard owes his present success to this movement. But, unfortunately, this has made his success a little too easy. I do not believe that the origin and- destiny of-man can be defined in such vague terms. A text that is so ambiguous that people whose views on its subject matter are diametrically opposed can read it with equal enthusiasm cannot be wholly satisfying. And I suppose that this is why, in spite of its many insuring and luminous passages, it is tedious to read 'the book from cover to cover. Having avoided so. many decisive issues, it can serve only as a new and powerful pointer towards problems that it leaves as unsolved as before.

Sir Peter Medawar on the same text

Thanks to a friend for sending in this piece when I sent him the Polanyi piece.

Everything does not happen continuously at any one moment in the universe. Neither does everything happen everywhere in it.

There are no summits without abysses.

When the end of the world is mentioned, the idea that leaps into our minds is always one of catastrophe.

Life is born and propagates itself on the earth as a solitary pulsation.

In the last analysis the best guarantee that a thing should happen is that it appears to us as vitally necessaryThere are no summits without abysses.

This little bouquet of aphorism, each one thought sufficiently important by its author to deserve a paragraph to itself, is taken from Père Teilhard's The Phenomenon of Man. It is a book widely held to be of the utmost profundity and significance; it created something like a sensation upon its publication in France, and some reviewers hereabouts called it the Book of the Year --- one, the Book of the Century. Yet the greater part of it, I shall show, is nonsense, tricked out with a variety of metaphysical conceits, and its author can be excused of dishonesty only on the grounds that before deceiving others he has taken great pains to deceive himself. The Phenomenon of Man cannot be read without a feeling of suffocation, a gasping and flailing around for sense. There is an argument in it, to be sure --- a feeble argument, abominably expressed --- and this I shall expound in due course; but consider first the style, because it is the style that creates the illusion of content, and which is a cause as well as merely a symptom of Teilhard's alarming apocalyptic seizures.

The Phenomenon of Man stands square in the tradition of Naturphilosophie, a philosophical indoor pastime of German origin which does not seem even by accident (though there is a great deal of it) to have contributed anything of permanent value to the storehouse of human thought. French is not a language that lends itself naturally to the opaque and ponderous idiom of nature-philosophy, and Teilhard has according resorted to the use of that tipsy, euphoristic prose-poetry which is one of the more tiresome manifestations of the French spirit. It is of the nature and reproduction that progeny should outnumber parents, and of Mendelian heredity that the inborn endowments of the parents should be variously recombined and reassorted among their offspring, so enlarging the population's candidature for evolutionary change. Teilhard puts the matter thus: it is one of his more lucid passages, and Mr Wall's translation, here as almost everywhere else, captures the spirit and sense of the original.

Reproduction doubles the mother cell. Thus, by a mechanism which is the inverse of chemical disintegration, it multiplies without crumbling. At the same time, however, it transforms what was only intended to be prolonged. Closed in on itself, the living element reaches more or less quickly a state of immobility. It becomes stuck and coagulated in its evolution. Then by the act of reproduction it regains the faculty for inner re-adjustment and consequently takes on a new appearance and direction. The process is one of pluralization in form as well as in number. The elemental ripple of life that emerges from each individual unit does not spread outwards in a monotonous circle formed of individual units exactly like itself. It is diffracted and becomes iridescent, with an indefinite scale of variegated tonalities. The living unit is a center of irresistible multiplication, and ipso facto an equally irresistible focus of diversification.

In no sense other than an utterly trivial one is reproduction the inverse of chemical disintegration. It is a misunderstanding of genetics to suppose that reproduction is only 'intended' to make facsimiles, for parasexual processes of genetical exchange are to be found in the simplest living things. There seems to be some confusion between the versatility of a population and the adaptability of an individual. But errors of fact or judgement of this kind are to be found throughout, and are not my immediate concern; notice instead the use of adjectives of excess (misuse, rather, for genetic diversity is not indefinite nor multiplication irresistible). Teilhard is for ever shouting at us: things or affairs are, in alphabetical order, astounding, colossal, endless, enormous, fantastic, giddy, hyper-, immense, implacable, indefinite, inexhaustible, extricable, infinite, infinitesimal, innumerable, irresistible, measureless, mega-, monstrous, mysterious, prodigious, relentless, super-, ultra-, unbelievable, unbridled or unparalleled. When something is described as merely huge we feel let down. After this softening-up process we are ready to take delivery of the neologisms: biota, noosphere, hominsation, complexification. There is much else in the literary idiom of nature-philosophy: nothing-buttery, for example, always part of the minor symptomatology of the bogus. 'Love in all its subtleties is nothing more, and nothing less, than the more or less direct tract marked on the heart of the element by the psychical converge of the universe upon itself.' 'Man discovers that he is nothing else than evolution become conscious of itself,' and evolution is 'nothing else than the continual growth of. ... 'psychic' or 'radial' energy'. Again, 'the Christogenesis of St Paul and St John is nothing else and nothing less than the extension ... of that noogenesis in which cosmogenesis ... culminates'. It would have been a great disappointment to me if Vibration did not did not somewhere make itself felt, for all scientistic mystics either vibrate in person or find themselves resonant with cosmic vibrations; but I am happy to say that on page 266 Teilhard will be found to do so.

NG -

You are a fluent reader - you read what you know I intended to write. I am a proof-reader/editor - unable to see my own typos or structural inaccuracies until I post - then they leap out at my critical eye! Thanks for the tip...I'll look harder next time. JSK

Excellent little piece/exposé on Woodrow Wilson - the hero of the Versailles Peace Treaties - as I learnt from studies in the early/mid 1960s. I book by Susie CHOW (Head of Japanese at Macquarie U - deceased) about her grand-father - a Japanese diplomat to the US pre-The Great War - then post-war the Ambassador - makes most clear his anti-Chinese, anti-Japanese sentiment. And also exposes his behind the scenes urging/encouragement of the Peace Treaties presence of William Morris Hughes from Australia and his virulent up-front racist sentiment defeating the clauses Japan - as an ally - wished included. "The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara's Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930" Misuzu Hanihara Chow & Kiyofuku Chuma - Palgrave Macmillan 2016. More good writing/endorsement from Wolf re Citizens' Juries! Appreciating your quirky inclusions - The Rat which loved Spaghetti! Interesting background to the Gay resignation - though her apology for being critical of Zionist Israel was not a courageous moment. Teilhard de Chardin - excellent dismissal - makes me think of Paul Coelho one of whose books I tried to read years ago - a similar sense of mystical nonsense - turgid with the grand pronouncements but totally unconvincing.