And then there was one ;(

An overflow newsletter. Expect another on Sunday — or maybe Saturday.

A metaphor, a hack, a ladder

On the difficulty of telling yourself the truth

I wrote a couple of pieces for apolitical a few years ago, but didn’t persevere. I then got an invitation to discuss my experience with the inevitable internal review and had a good discussion. Saying that apolitical seemed very optimised to its audience to me, which of course is its right. However its eagerness to demonstrate its usefulness to readers’ careers in the civil service, it rather played itself out of what I wrote about. I hoped what I wrote was useful, but it also often tried to look at more fundamental things about the way particular approaches were keeping us from progress. Anyway, they seemed to understand this point of mine and said they’d be interested in publishing more stuff from me. So months later when I produced the essay below, I sent it off and they seemed keen to publish it.

Then I was told that I needed to answer three framing questions — which you’ll see below. I wrote back

I can see that this could be a good template for lots of articles, including some of the kinds of articles that I write, but this isn’t that kind of article. Is it possible to vary this template at all? Would you consider labelling it a special essay or ‘think piece’?

Anyway the answer was …

No.

Then I worked out a way to meet the requirement that, courtesy of a bit of playfulness actually improved it.

The problem: The fat relentless ego.

Why it matters: It’s not about you.

The solution: Unselfing.

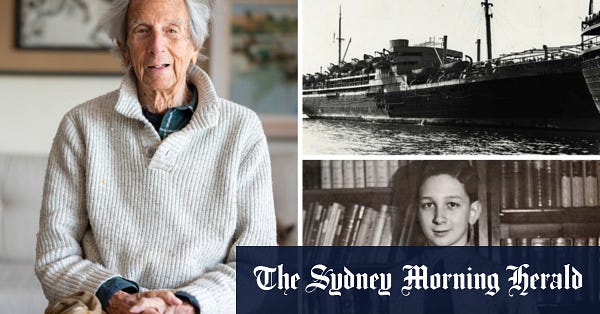

You may have done an exercise like the one illustrated here where you draw a picture and then you do it again with the picture upside down. Having done it years ago I can assure you it made a huge difference. It's a lovely illustration of Richard Feynman’s assertion that, in science, “you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool”.

The 'before' picture is 'theory-laden'. But the exercise shows you how bad your theory is — how what you know for sure just ain't so. The ‘before’ picture is laden with ill-judged shortcuts — an eye is a white pinched egg shape, framed by eyebrows and eyelashes with a dark pupil in the middle. Well no it’s not. Not when you look carefully and then try drawing what you see. Who’d have thought that would be a better way to draw?

The exercise demonstrates the way in which learning to see is, at the same time, an unlearning of how not to see. Yet the way of seeing you must unlearn is already second nature to you. Keynes expressed this difficulty when it comes to changing our framework of thought: "The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping the old ones, which ramify, for those brought up as most of us have been, into every corner of our minds."

Yet the drawing exercise is richer. It shows us how, even after we stop getting theory so wrong, we’ve only just begun. We now need to reassemble bundles of tacit knowledge and reconfigure them around whatever task is at hand. Each bundle on its own (looking, drawing) and also in connection (looking to draw and then looking back with some renewed focus for our attention). Getting better at this is not explicitly conceptual. It’s a matter of practising, learning, and integrating what we've learned and then doing it again. We’re building ‘muscle memory’.

‘Bad for my brain, body and soul’: Rory Stewart on politics, privilege and podcast stardom

He’s been an author, a diplomat, a soldier, a cabinet minister – and still dreams of changing the world. The recovering Tory talks about his friendship with Alastair Campbell, the gaffes that haunt him and his fears about Boris Johnson

Connected through an English friend who was chief fund-raiser for his campaign to become Lord Mayor of London, I worked with Rory Stewart on building in the idea of citizens’ juries into his campaign. Rory was interested in my ideas and I was able to introduce two stellar campaigners from the US — Joe Trippi who as campaign manager took Howard Dean from outsider to Democratic frontrunner and whose digital team were then picked up by the Obama campaign four years later and Dane Waters who’d worked with one of the last sane Republican presidential candidates — John McCain. Anyway, COVID intervened and Rory couldn’t sustain his candidature for the length of time necessary to win, and so he pulled out.

One depressing takeout from the process was the response of focus groups to the idea that Rory would establish a standing citizen’s council chosen by lot to advise him on. Even when it was pitched to them as ensuring their continuing say in Rory’s discharge of his duties as their representative, they didn’t like the idea. They said they didn’t see any point in ‘another committee’. What they wanted was a strong leader. Anyway, my friend Danny sent me this profile of an intriguing fellow. Rory seems to be putting himself about quite a bit right now — not just with the podcast that’s the subject of the article but also with podcast series like this one on argument.

And here’s a few paragraphs from the profile.

The son of a spy and former colonial official, Stewart was born in Hong Kong, although his family hails from Perth and Kinross and he spent much of his childhood in Kensington (he once jokingly described himself as “lower-upper-middle class”). He was sent to boarding school in Oxford at eight, then attended Eton. “It made me very bad at dealing with women,” he says. “I was in an all-male environment until I was 18. It took me a long time to learn anything about British society. These schools are like islands floating in the sea. They have no connection. You might as well be in a space camp.”

He spent five months as a soldier in the Black Watch after finishing school, before studying at Oxford, where he attended a single meeting of the Bullingdon Club, the notorious all-male dining club whose members have included Boris Johnson and David Cameron. “It seemed to be an extreme statement of a very unpleasant vision of a class system that was completely undignified,” he recalls. “I thought it was unpleasant. I thought people should be ashamed of that kind of stuff.” …

After leaving parliament, Stewart became a fellow at Yale, teaching politics and international relations. He doesn’t miss being a politician. “I found that it was very, very bad for me, for my personality type,” he says. “It brings out the worst in me. I thought it was bad for my brain, my body, my soul. I became anxious. I didn’t like myself. I really hated the fact that I would end up on the one hand being critical of party leaders and on the other hand creeping up to them and being superpolite to them, hoping I was going to get a job, and then I’d really hate myself.”

New world order anyone?

Zoltan Pozsar from Credit Suisse describes the way he sees the tectonic shifts beneath our feet. His focus is, unsurprisingly the state of the markets and in particular inflation, but there are lots of moving parts. Thanks to Michael Griffith for drawing it to my attention.

Inventory for supply chains is what liquidity is for banks. In 2007 -08, big banks ran on “just-in-time” liquidity: the dominant form of liquidity was market liquidity, for which you could always sell assets into a deep market without moving prices, so you did not have to have liquidity reserves at the central bank. Similarly, big corporations today run “just-in-time” supply chains for which they assume that they can always source what they need without moving the price. But not really: the U.S. military has to wait a little bit as Raytheon “will take a little while”; Taiwan and Saudi Arabia have to wait as well until the conflict in Ukraine is over; and if your washing machine broke recently, you’ll have to wait a bit too until defense contractors are done buying them up to rip chips out to make missiles.

We’re borrowing from “here” to make things “there”. Do you remember the three units of Minsky? Hedge units can cover their payments from their incomes. Speculative units have to borrow to be able to make payments. And Ponzi units can make their payments only if they sell some of their assets and are thus the most exposed to rising interest rates. As our chip examples demonstrate, Minsky would classify our military supply chain s as “speculative” units at best, which are exposed to a further escalation of geopolitical tensions that could easily turn them into Ponzi supply chains. We can also apply Minsky’s framework in Europe, where German y can’t cover its payments without Russian gas and the government is asking citizens to conserve energy to leave more for industry.

Minsky moments are triggered by excessive financial leverage, and in the context of supply chains, leverage means excessive operating leverage: in Germany, $2 trillion of value added depends on $20 billion of gas from Russia …

To ensure that the West wins the economic war – to overcome the risks posed by “ our commodities, your problem”; “chips from our backyard, your problem”; and “our straits, your problem” – the West will have to pour trillions into four types of projects starting “yesterday ”:

(1) re -arm (to defend the world order)

(2) re -shore (to get around blockades)

(3) re -stock and invest (commodities)

(4) re -wire the grid (energy transition)Similar to how Basel III was the “tab ” associated with the Great Financial Crisis, the above list is the tab for the currently unfolding “Great Crisis of Globalization”.

The Conservatives are imploding

The nightmare scenario for Britain's governing party is coming into view

Couldn’t happen to a nicer bunch of politicians.

The wheels are coming off the Conservative Party. This week, in the polls, the party averaged just 31% of the national vote. This is John Major in 1997 territory, or William Hague in 2001, both of whom were humiliated at the ballot box. As I said on Twitter, Britain’s governing party is now in the fast lane toward electoral wipeout.

In fact, remarkably, half the people who voted for the party only 989 days ago have now abandoned it. This has given Keir Starmer and the Labour Party a commanding 11-point lead. Meanwhile, the share of voters who think the next election will deliver another Conservative majority has collapsed to just 19%.

Simon Schama on the right to irreverence

A nicely written piece by Schama. It begins:

Is nothing sacred? Yes, the right to irreverence. The health of a free, democratic society can be measured by its protection of disrespect, so long as the right to offensiveness does not extend to the threat, much less the enactment, of physical harm.

Having read this, I expected to see some commentary on threats to the right to irreverence from both left and right forms of intolerance. Schama is horrified by the right, as well he might be. Alas there was nothing on the broader expansion of the right to reverence from what might be called the left, but which is perhaps better thought of as our managerial elite. Our managerial elite flee from discomfort like Dracula from a wooden stake. And that empowers all the cancelation campaigns and general confusion around the difficult issues we should be discussing. For instance the extent to which differences in sex, gender, sexual orientation, class, race and whatever mix of genetics and culture produces them, might be treated as an asset to be affirmed rather than denied on pain of ex-communication.