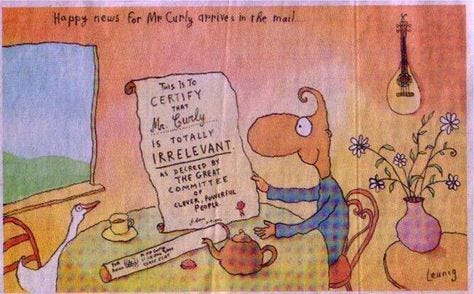

Intergenerational amnesia

This post set off several trains of thought for me. The first is the cycle of amnesia. That the young make the same mistakes as the old made when they were young is understandable and perhaps to be expected. But we might ask what mechanisms we have in place to try to do better. Old authority structures didn’t have this problem (I’m thinking) but at the high cost of a lot of authoritarianism from oldies. I vowed when young that if my kids asked “why?” I wouldn’t say “Because I say so” - an expression that incensed me as a kid. I still think it’s a dumb question.

But of course “Because I say so” is a response to a genuine problem. It’s a conversation stopper - and that’s necessary if the question “why” is really counterfeit currency which it is when it really means “I don’t want to do that, so I’ll just throw anything at it and keep the guy busy while I figure out what to do next”.

In that situation I’d say “no whys”, which does actually get to the heart of the issue (I know you’re stalling and prevaricating not actually investigating in good faith). But it’s not much better. Oh well, there you go. Progress is slow.

Then there’s government by amnesia, the process whereby governments announce their intention to sort something out that’s never been sorted out - despite endless previous announcements. The essence of government by amnesia is to proceed as if this time it will be different. But you don’t tell us why it will be different. It’s just that there’s an air of “how hard can it be now the adults have arrived?” So we’ll cut red tape. We’ll improve school performance - and so on. But you’ve heard me on that before.

As someone pointed out to me after they’d spent some time in Teach for Australia teaching indigenous kids in outback Australia, the core policy of self-determination is evidently in some tension with ‘closing the (economic) gap’. Shouldn’t those who want to improve the lives of indigenous folk focus on that, try to get some clarity around that. Well, they can’t. Because it’s uncomfortable. And so, we go on and on.

The other thing it made me think of is the failure of the left to come up with any response to the developments of the last few decades or the transformed political landscape it’s brought about. My view is that the right have some powerful things to say about what’s wrong while their reflex fantasies stand in as solutions (the apocalypse and antichrist anyone?). The pity of it is that the right have much more power. So we’re getting their solutions. One way to explain what’s gone wrong with the left is via a simple idea from one of the alt-right’s intellectual heroes - James Burnham.

Gods, whether of Progress or the Old Testament, ghosts of saintly, or revolutionary, ancestors, abstracted moral imperatives, ideals cut wholly off from mere earth and mankind, utopias beckoning from the marshes of their never-never-land—these, and not the facts of social life together with probable generalizations based on those facts, exercise the final controls over arguments and conclusions. Political analysis becomes, like other dreams, the expression of human wish or the admission of practical failure.

Measurement

A LinkedIn post from Sandra Milligan, Executive Director of Melbourne Metrics which builds student .

I’m on holiday, so my usual concerns – assessment, NAPLAN (!), testing, exams –should have been out of mind, for once.

But there I was at an art gallery in Budapest staring at a 1795 watercolour monotype of the great English scientist, Isaac Newton, by the great English artist William Blake. That bought it all flooding back. In one of those uncanny coincidences, I had recently read about this artwork, twice: first only weeks ago in one of Nicholas Gruen’s always stimulating blogs, and then in my holiday reading – a book by James Vincent’s history of measurement (Beyond Measure, Faber 2022).Blake’s image is powerful. Vincent described it thus: Blake is satirising (Newton’s) blindness: “engrossed in his calculations … ignorant to the wonders of the world around him. He is hunched, not heroic; obsessed with his measurements and so missing entirely what his compass cannot contain”.

Vincent explains: “to measure is to choose; to focus your attention on a single attribute and exclude all others”.

In fact, the word precision comes from the Latin ‘praecisio’ meaning to cut off. Blake was depicting his struggle with the the dangers inherent in this ‘cutting-off’, believing that the emerging reliance on rationality and reason in the Enlightenment risked reducing human attention and aspiration to just what can be measured, threatening human happiness and limiting capability.

Vincent’s history also charts this struggle. He asserts the power of good measurement to be a ‘tutor to humanity’, and an inprition of philosopher and scientists, and used to fix the greatest problems in society, education included. But he also warns that this power can become an ‘overlord’, and gives many examples of its use as an instrument of brutality, persecution, manipulation and injustice.

I suspect Blake and Vincent alike would recognise as instruments of overlording in Australian schooling measures including NAPLAN, phonics tests and the other standardised, ‘precise’ measures of aspects of literacy and numeracy. It’s not that they are bad measures in and of themselves. It’s because Blake’s fears have been realised: the measures have become sterile proxies for educational success, narrowing the gaze of politicians and society at large. They have become the distorting glasses through which young people are too often seen and measured up. In their ‘precision’ these instruments cut off much of the grand potential of humans, what they do and can be, that Blake so passionately defended.

Vincent’s book is a great read, particularly the first 20 pages, for teachers who put numbers on their students’ work, yet want to be clear-eyed about the dangers. I’m planning to hang a print of Blake’s painting in my office at work, just to remind me to be careful about what I measure, and why.

I thought this was really good - even if you may not agree with Rory. I loved his dissonant confession of his passionate embrace of the particularity of (Burkean) conservatism and of the ‘weirdness’ that necessarily comes with it. It’s about a year old.

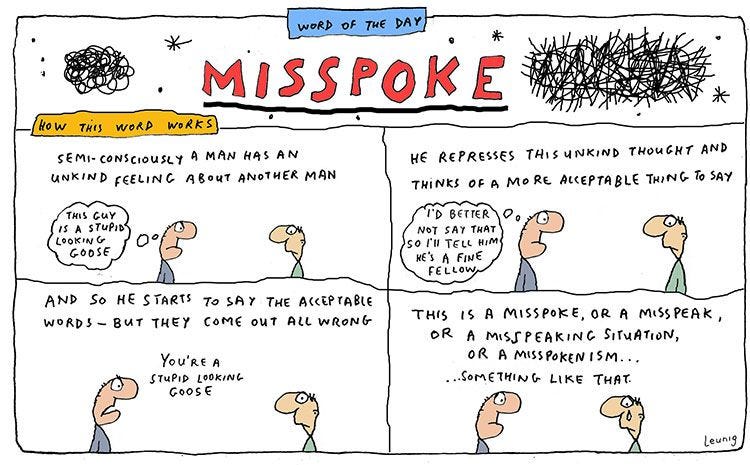

Goodhart’s Law

My friend Felix Martin on the foibles of management by target.

Goodhart’s Law – the adage that that when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure – describes a central paradox of data-driven policy-making. It used to be confined to technical areas such as central banking, where it was first formulated to explain the breakdown of monetarism in the 1970s. Today it confounds government policy across a much broader range of fronts – driving the widespread perception of state failure that is fuelling the populist revolt.

Fifty years ago, policymakers were newly confident that they knew how to bring inflation down. The economist Milton Friedman and his “monetarist” followers had come up with a simple solution based, for the first time, on rigorous scientific analysis of the relevant economic data. Ensure that the money supply grew only slowly, they taught, and inflation would come under control.

At first it worked. Central bankers tamed money growth and inflation fell. But then the trusty relationship began to glitch. The money supply remained contained, but inflation roared back anyway.

The British economist Charles Goodhart identified what had gone wrong. The relationship between the money supply and inflation had indeed been stable, so long as policymakers left the money supply to its own devices. Once they declared it to be a policy lever, however, banks changed how they behaved. Lenders busily improvised alternative gushers of liquidity not captured in the measured money supply, even as central bankers kept their fingers in the dyke. The target had been gamed. The link between money and inflation came unstuck.

Goodhart pointed out that this perverse result reflected a general rule. “Any observed statistical regularity” he said, “will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.”

For central bankers, Goodhart’s Law became a watchword for the dangers of relying on data-driven policy rules to manage the messy business of reality. Today, those same dangers are playing havoc with a much broader range of government policies. Two high-profile recent examples from the United Kingdom serve to demonstrate the point.

The first is immigration. Free movement of people between the European Union and Britain came to an end on December 31, 2020. Britain’s elected leaders were henceforth exclusively in charge, and the end of a politically corrosive decade of broken promises to reduce the number of new arrivals seemed finally to be at hand. Newly elected Prime Minister Boris Johnson leapt eagerly to the task. On 1 January 2021 he introduced a brand-new, “points-based” system specially designed to take back control of immigration.

Yet far from the numbers falling, they rocketed to a new, all-time high. Average annual net immigration in the four years after the change tripled relative to the decade before – from 209,000 to 662,000...

The root cause of this epochal policy failure was that the new, data-driven policy proved remarkably easy to game. The points system presented a conveniently visible target. A vibrant industry dedicated to hitting it sprouted overnight. As a result, the system’s meticulously designed settings rapidly got out of sync.

The social care industry illustrates what occurred. Because of its higher need for immigrant labour, the criteria for set care sector visas were looser than for other jobs. Nonetheless, by calibrating them carefully on historical trends, the government forecast a mere 6,000 successful applications per year.

Instead, between 2019 and 2023, the number of care firms registered to sponsor visas exploded by over 200%. At the same time, many immigrants on care-related visas worked in the sector for only a few months, before moving on to other jobs. Nearly 680,000 carers and their dependents were admitted over 2021-24 – twenty times the government’s forecast. The care sector route became a short-circuit to circumvent the new thresholds imposed elsewhere. Britain’s new immigration policy had met its match in Goodhart’s Law.

The same mechanism explains another of the UK’s most high-profile policy challenges: the unplanned explosion in its sickness benefit bill...

Between the decade before 2020 and the four years after that date the average quarterly inflow of new incapacity benefit claimants doubled, from 61,000 to 121,000. That added stress to the public finances on a macroeconomic scale. By 2023, the additional 440,000 working-age adults inactive on health grounds had collectively added 0.6 percentage points to the UK’s budget deficit...

Once again, the principal culprit is a points-based system that is vulnerable to being gamed. The OBR found that the proportion of claimant applications meeting the conditions to access benefits has rapidly increased in the last few years – despite surveys showing many illnesses in steady decline...

The failure of elected leaders to make good on their policy promises is the main fuel of the populist wildfire that has swept through liberal democracies for the last decade. In today’s intensely polarised era, it is tempting to blame incompetence, bad faith, or even the enemy within.

The lesson of Goodhart’s Law is that the real culprit may be more mundane. All too often, data-driven policy-making is the disease for which it claims to be the cure.

Decadence: or TAAS (Transgression as a service)

Needless to say, I don’t agree with the comment in the tweet. Jess preens herself in the safety and wealth of a home built by Western liberalism (with all its faults) and finds a new, compelling way to offer us a transgressive ‘take’ while she gets on with more important, mundane things like brushing away blemishes. She’s mainlining narcissism and, because she’s got a good turn of phrase, we’re supposed to be impressed, not grossed out at a civilisation utterly bereft of its moorings.

War and masculine honour in Ukraine

Scott Alexander runs an essay competition every year on his website Astral Codex Ten. Here’s a short tease to get you reading one of the finalists’ essays.

In the winter of 2022 I was unhappily working at a dull but decently compensated IT job, which I had come upon at last after four years of phoning it in at college and abandoning my brief stint as an MMA Fighter/Porn Store Security Guard...

On February 24th, 2022, Russia began its full scale invasion... Ukrainian foreign minister Dymytro Kuleba announced the creation of the “International Legion For The Territorial Defense Of Ukraine”...

One day as I was being lectured by a female HR representative for leaving my (cloth, non-medical) mask off for too long during lunch, I could barely hear what she was saying. All I could think of were the uncounted men across untold generations who had lived and died as warriors, with all the honor and pain that entailed. I thought of how men in Ukraine right now lived a modern version of that, while I allowed myself to be subject to the feminized safteyist ideology of everyday civilization...

War Stories

“This is not like Iraq” the Ukrainian recruiting officer soberly told me with a thick accent. “You have 50% chance of dying.” That wasn’t actually true, but it was a lot closer to being true than almost anything you can voluntarily sign up for in an organized way. I decided it was worth it.

It wasn’t long before I was shivering in a trench, ducking slightly at the occasional whistle of artillery... One of my friends, a Greek who once told me he had considered joining ISIS “for the aesthetic” had enough and asked me to hold the other end of the tarp steady while he fixed it. This was dangerous as it required climbing out of the trench. No sooner had he triumphantly tied the knot than a shot rang out and we heard a little “woosh”...

More serious still were FPVs, or suicide drones. I remember crouching down in the trench to the whine of propellers while I contemplated what the instant of death would feel like...

Takeaways

I don’t personally hate the Russians the way most Ukrainians do, but I also genuinely do not feel bad about the people that I’ve killed...

I think our modern culture has built a very strong taboo around certain parts of the human experience... but I can’t help but roll my eyes a little bit at the idea that there is nothing cool or ennobling about war... Have you ever felt the rush of seeing an enemy tank destroyed? There is and I won’t pretend there isn’t...

But I also think we should be hesitant to dismiss the much more mixed view of violence which has traditionally been held by almost every society before WWI. The concept of honor, of which suffering and the risk of bodily harm and even death are active ingredients, is a powerful human instinct which cannot be hand waved away.

Before my experiences in Ukraine I used to desperately feel like I had to do something, without even necessarily knowing what it was. I think a lot of young men feel this way, and have felt this way since prehistory... From ancient indo-european tradition we have the concept of the Koryos, a group of young unmarried men who would spend some time living outside of normal society, raiding rival tribes and living by violence...

Once, a few days before we were to return to the front, I snorted ecstasy with a comrade in a Kyiv strip club. “If we die” I told him, “we’re going to come back as flowers.”...

Some [of my comrades] are still in the Koryos, fighting to this day. Others have left and integrated or reintegrated into society. Still others have now come back as flowers. I will remember them for the rest of my life.

Quiggin on Nuclear

John Quiggin summarises the case against nuclear. He doesn’t weigh in on why Korea and China seem to be doing better than the examples he quotes. And he doesn’t allay my fears on the shape of the cost curve of taming intermittency as renewables share of generation grows. Still, we keep being promised those small modular reactors and they’re always just a few years away. Sadly our system only cognises choices in terms of culture wars.

The culmination of Donald Trump’s state visit to the UK was a press conference at which both American and British leaders waved pieces of paper, containing an agreement that US firms would invest billions of dollars in Britain.

The symbolism was appropriate, since a central element of the proposed investment bonanza was the construction of large numbers of nuclear reactors, of a kind which can appropriately be described as “paper reactors”.

The term was coined by US Admiral Hyman Rickover, who directed the original development of nuclear powered submarines.

Hyman described their characteristics as follows:

It is simple.

It is small.

It is cheap.

It is light.

It can be built very quickly.

It is very flexible in purpose (”omnibus reactor”)

Very little development is required. It will use mostly “off-the-shelf” components.

The reactor is in the study phase. It is not being built now.

But these characteristics were needed by Starmer and Trump, whose goal was precisely to have a piece of paper to wave at their meeting.

The actual experience of nuclear power in the US and UK has been an extreme illustration of the difficulties Rickover described with “practical” reactors. These are plants distinguished by the following characteristics:

It is being built now.

It is behind schedule

It requires an immense amount of development on apparently trivial items. Corrosion, in particular, is a problem.

It is very expensive...

The most recent examples of nuclear plants in the US and UK are the Vogtle plant in the US (completed in 2024, seven years behind schedule and way over budget) and the Hinkley C in the UK (still under construction, years after consumers were promised that that they would be using its power to roast their Christmas turkeys in 2017)...

Hope has therefore turned to Small Modular Reactors. Despite a proliferation of announcements and proposals, this term is poorly understood.

The first point to observe is that SMRs don’t actually exist. Strictly speaking, the description applies to designs like that of NuScale, a company that proposes to build small reactors with an output less than 100 MW (the modules) in a factory, and ship them to a site where they can be installed in whatever number desired...

Most of the designs being sold as SMRs are not like this at all. Rather, they are cut-down versions of existing reactor designs, typically reduced from 1000MW to 300 MW. They are modular only in the sense that all modern reactors (including traditional large reactors) seek to produce components off-site. It is these components, rather than the reactors, that are modular. For clarity, I’ll call these smallish semi-modular reactors (SSMRs). Because of the loss of size economies, SMRs are inevitably more expensive per MW of power than the large designs on which they are based.

Over the last couple of years, the UK Department of Energy has run a competition to select a design for funding. The short-list consisted of four SSMR designs, three from US firms, and one from Rolls-Royce offering a 470MW output. A couple of months before Trump’s visit, Rolls-Royce was announced as the winner...

So, where will the big US investments in SMRs for the UK come from? There have been a “raft” of announcements promising that US firms will build SMRs on a variety of sites without any requirement for subsidy. The most ambitious is from Amazon-owned X-energy, which is suggesting up to a dozen “pebble bed” reactors...

Pebble-bed reactor designs have a long and discouraging history dating back to the 1940s. The first demonstration reactor was built in Germany in the 1960s and ran for 21 years, but German engineering skills weren’t enough to produce a commercially viable design... As of 2025, the company is seeking regulatory approval for a couple of demonstrator projects in the US.

Meanwhile, China completed a 10MW prototype in 2003 and a 250MW demonstration reactor, called HTR-PM in 2021. Although HTR-PM100 is connected to the grid, it has been an operational failure with availability rates below 25%...

When this development process started in the early 20th century, China’s solar power industry was non-existent. China now has more than 1000 Gigawatts of solar power installed. New installations are running at about 300 GW a year, with an equal volume being produced for export. In this context, the HTR-PM is a mere curiosity.

This contrast deepens the irony of the pieces of paper waved by Trump and Starmer. Like the supposed special relationship between the US and UK, the paper reactors that have supposedly been agreed on are a relic of the past. In the unlikely event that they are built, they will remain a sideshow in an electricity system dominated by wind, solar and battery storage.

Why are so few hot countries rich?

I’ve often wondered about this - though in a different form to the question above. I wonder how come the wealthiest counties were near the Mediterranean in the ancient world and up to the Renaissance, and then somehow the torch was passed to Northern Europe. Anyway, here’s a brand new theory - at least according to its author. It’s a long post so I got Claude to summarise it, but it’s worth your while going to the post for the maps!

Anyway, in the process of summarising it, Claude also critiqued it! You can thank me later.

Central Argument

The author presents a novel geographic theory: warm countries are poorer primarily because their populations live in mountains to escape equatorial heat, and mountains dramatically increase transportation costs, reduce trade, cause ethnic fragmentation (Balkanization), and breed conflict—all of which suppress economic development.

The author argues this mountain factor has been overlooked in favor of other explanations like temperature, disease, institutions, or colonialism. While acknowledging these factors matter, the author claims the altitude trade-off is the key missing piece: equatorial populations chose between lowland poverty (heat, humidity, disease) and highland poverty (isolation, conflict, poor infrastructure).

The Logic Chain

Humans evolved in African highlands (like Kenya’s Rift Valley) where temperatures are moderate year-round, not in hot lowland tropics

At sea level near the equator, heat and humidity make people unproductive and diseases thrive

So populations moved to mountains where it’s cooler and drier (temperature drops ~4-9°C per 1000m)

But mountains create massive economic costs: expensive infrastructure, limited trade, ethnic isolation, and conflict

Core Examples

Colombia: The three largest cities—Bogotá (12.7M), Medellín (4.4M), and Cali (4.2M)—are all in mountains at high altitude. Bogotá sits at 2,600m elevation, making it 14°C cooler than coastal Barranquilla despite being further from the equator. The Spanish established it inland in the mountains in 1538, just decades after discovering America, because coastal flatlands were deadly.

Ethiopia: Africa’s second most populous country, with capital Addis Ababa actually colder than Lisbon, Portugal. The population concentrates in the highlands of the Rift Valley mountain range.

The Andes pattern: Latin American population dramatically concentrates along the Andes mountain chain running through multiple countries, visible on population density maps.

Contrast with temperate regions: In Italy, people live in every available plain. In Colombia, people live in the mountains—the opposite pattern.

Supporting Data Point

The author shows that the closer a capital city is to the equator, the higher its elevation. Jerusalem (the highest capital in a developed country) is only 750m above sea level, while equatorial capitals routinely exceed 1,000m.

Critique

The theory is intriguing but has significant weaknesses. The author dismisses East and South Asia as showing “much weaker” patterns, yet these regions contain billions of people living in hot lowlands (Ganges, Yangtze, Mekong river valleys). If the theory were truly fundamental, it shouldn’t have such massive exceptions. The author also oversimplifies institutional arguments (the Acemoglu critique is somewhat strawmanned) and doesn’t adequately explain why some lowland tropical areas like Singapore became wealthy with air conditioning while others haven’t, despite AC being widely available now. The causal arrows likely run in multiple directions simultaneously rather than mountains being “the most significant underdiscussed topic” as claimed.

Life at the bottom of the status hierarchy

Academia always seemed to me to be the best of jobs. That’s what my father thought. But fortunately I twigged early enough that careerism had more or less completely demolished it by the time it became a possibility for me. Anyway, as management numbers and salaries and journal profits swell, the little people can’t get a reply to an email.

This article has been in motion since January 2025. It was accepted by an international news platform, but they delayed its publication, to this day I have not heard back from them. ...

This is just one example. I have around seventy publications to my name, yet most of them have faced similar silences. ... These delays do not just waste time. They waste the life of an idea.

In academia, rejection is part of the process. Silence is not. For early-career scholars, especially those from marginalised backgrounds, the absence of a reply is not simply a neutral delay. It is a quiet act of exclusion that interrupts the flow of work, drains confidence, and leaves words locked in an uncertain waiting room. ... What is harder to survive is sending our labour into the void and never knowing if it reached a human eye.

This article is about writing on contemporary issues that require immediate attention. ... Contemporary commentary is ... often tied to unfolding events and relies on timely publication to make sense and have an impact. When weeks stretch into months without a word, the urgency fades. The context changes. The opportunity to intervene in the conversation is gone. ...

The weight of this silence does not fall evenly on every writer. ... For those without such access, there is only the submission portal or a generic email address, and then nothing. Many of us write from regional universities, in our second or third language, without institutional email IDs that signal status. Our work must cross not just intellectual barriers but also the invisible walls of geography, caste, class, and language. Silence reinforces these inequalities. ...

There are platforms that set an example of how things could be done. The Swaddle sends an automated response saying that if you do not hear from them within 24 hours, you should consider your submission as rejected. Economic and Political Weekly gives every submission a tracking number so contributors can follow its progress. Mainstream Weekly, Countercurrents, and The Print reply to rejections usually within two days. The Mooknayak English replies within 24 hours if they will proceed with your work or not. ...

I have known both rejection and silence, and I would choose rejection every time.

Behind the seventy articles I have published are more than a hundred rejections and an equal number of unanswered submissions. A rejection closes a chapter. It allows the writer to move on, to revise, to try elsewhere. Silence traps both the work and the person in a state where neither can advance. The harm is not only professional. It is emotional. It is the harm of being unseen. ...

Silence is not inevitable. ... An automated reply confirming receipt, even if machine-generated, can reassure a writer that their work has been received and logged. A statement on a website saying that if there is no response within a certain time the writer is free to submit elsewhere can remove the paralysis of waiting. A commitment to respond within a set period, even with a one-line “we will not be proceeding,” respects the time and emotional labour of the author. ... They require only the will to recognise that behind every submission is a person who has given something of themselves to the work. ...

Publishing is at its best when it is a dialogue. ... Rejection, when given clearly, keeps the dialogue alive. Silence ends it. Behind every submission is invisible labour. Ideas formed in stolen hours, revisions made between fieldwork or caregiving, sentences shaped in the middle of grief or exhaustion. ... Because in the end, it is not rejection that ends a voice, it is the silence that never lets it begin.

There I was minding my own business

And I came upon this fine aphorism.

Sometimes I simply remind patients that sooner or later they will have to relinquish the goal of having a better past.

Irvin D. Yalom

Following it up, I discovered this film made in the late 1990s, in good order and entirely free on YouTube. I watched it through and was glad I did.

Mining the moon

I know this is an official subject of us chatterers, but I’d never taken any real notice. Now I have. It’s all pretty speculative, but Helium 3 and quantum computing ey? Whodda thunk?

In Ad Astra, the 2019 Brad Pitt film, the Moon is shown as a place of highways, checkpoints, and corporate outposts – a frontier already carved up by commerce and conflict. That scene felt like science fiction, yet it is fast becoming reality. In anyone’s estimation, $300 million is a lot of money. Especially when it’s being spent on a gas from the Moon.

But this is no joke. The Washington Post revealed this month that Finnish firm Bluefors and American company Interlune have struck an agreement worth hundreds of millions of dollars to purchase tens of thousands of litres of lunar Helium-3. This is not just a commercial milestone – it is a political act that foreshadows how lunar governance may evolve.

Long before the first kilogram of lunar soil is heated, contracts are shaping ownership, pricing, and access to celestial resources. This early monetisation of the Moon highlights a growing clash between private profit and the principle of outer space as the “province of all mankind”...

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 prohibits claims of sovereignty and declares that space shall be “the province of all mankind”.

The Bluefors–Interlune deal is the largest private purchase of a natural resource from space, locking in up to 10,000 litres of Helium-3 annually for delivery between 2028 and 2037. At current valuations of roughly $20 million per kilogram – about $2,600 per litre – this is an order worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Bluefors, a leading supplier of dilution refrigerators for quantum computing, depends on Helium-3 to cool qubits to near absolute zero...

Earth’s production of Helium-3, derived mostly from tritium decay in nuclear stockpiles, is capped at 22,000–30,000 litres per year. With demand from quantum computing projected to surge, Interlune estimates that lunar reserves exceed one million metric tonnes, accumulated over four billion years of solar wind bombardment...

What makes lunar Helium-3 distinctive is that there is no mature international regulatory framework. Once courts recognise and enforce these contracts, private law will function as proto-governance, sidelining the deliberations of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.

This is where the gap between law and practice becomes stark. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 prohibits claims of sovereignty and declares that space shall be “the province of all mankind”. Yet it says little about ownership of extracted resources. The US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015 filled that gap domestically, granting American companies the right to own and sell resources mined from celestial bodies...

The Bluefors–Interlune contract is therefore a warning shot. It demonstrates that lunar governance will not be decided in slow UN negotiations alone, but in the brisk language of offtake agreements and delivery schedules. The profit motive and the commons principle are colliding in real time.

The choice facing the international community is not whether lunar mining will happen, but whether it will unfold under an exclusionary regime of first movers, or a compact that balances private initiative with shared benefit...

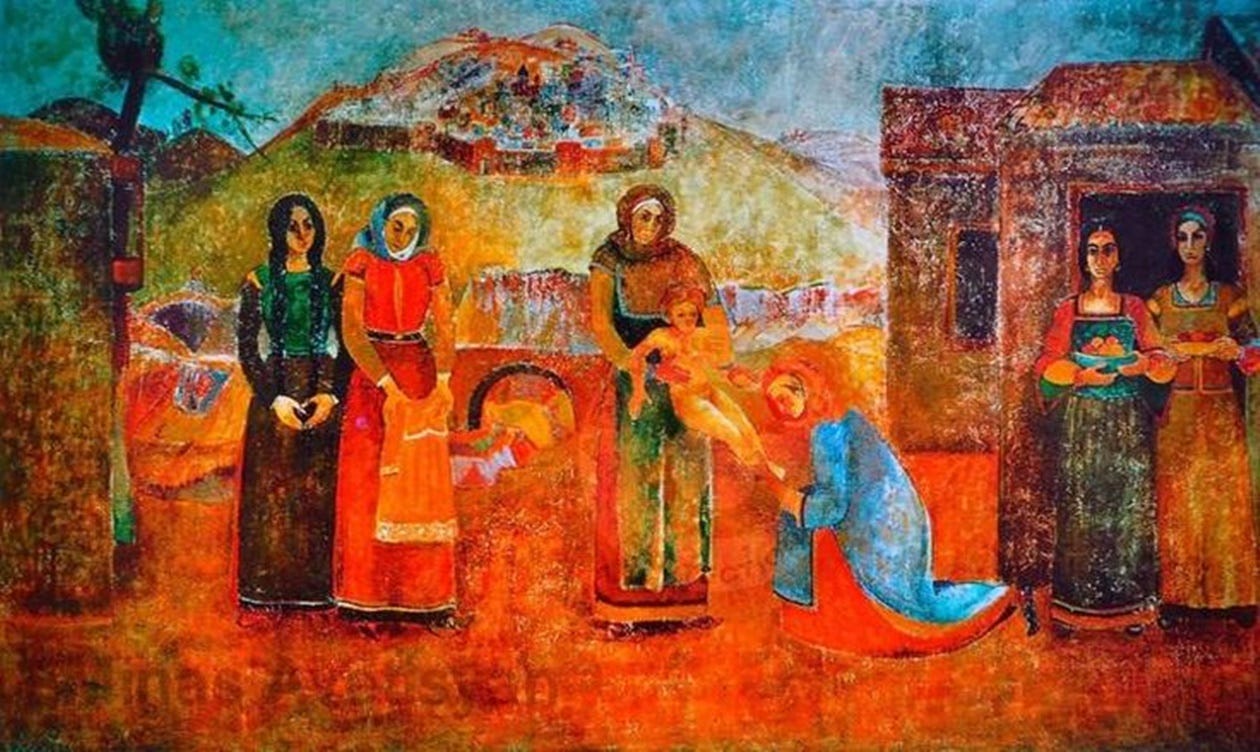

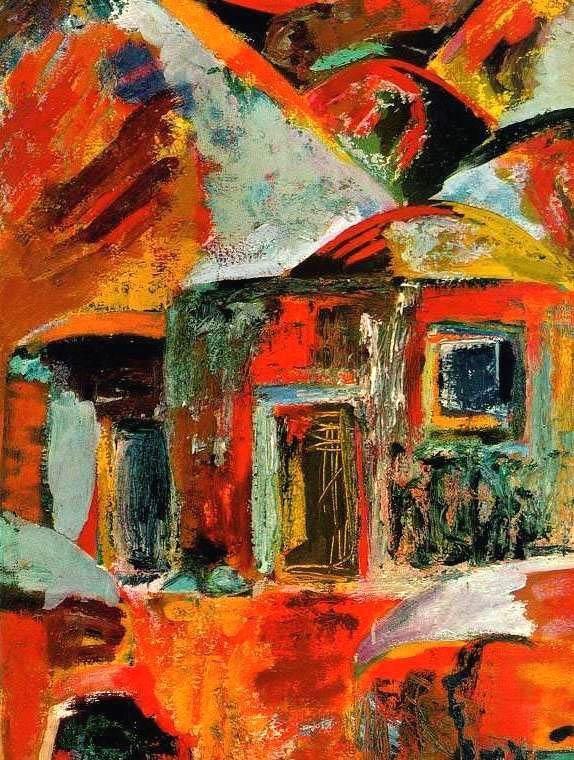

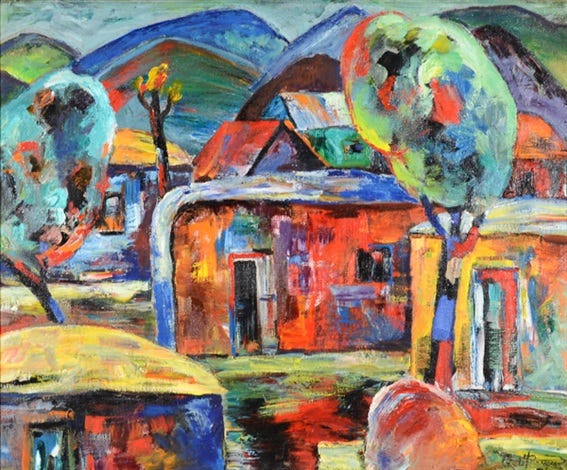

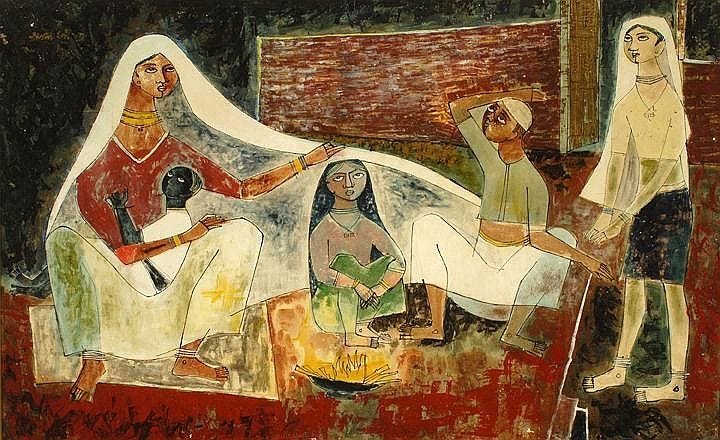

Minas Avetisyan, Armenian painter (July 20, 1928 — February 24, 1975)

Heaviosity Half Hour

Is on hiatus but, with any luck, will be back next week.

I couldn't agree more on the measurement piece - especially from my experiences as a long-term teacher - re measuring aspects of that process as if it proves things. I was not in Australia during the implementation of the travesty which is NAPLAN - but in another country where I had the freedom to assess my students in totally positive ways. No numbers on reports out of 10 or 100. Instead I wrote replies. No 'fails" - rather - rewards for completing all the elements of the class to the best of their competence. I won't say "ability" because I had no real way of "measuring" such a thing. It turned out my students loved my way of assessment and came to class - and then in the university's way - at the end of the year - evaluated my teaching so highly - that every year I achieved a luncheon along with two or three others with the Dean (which always came as a pleasant surprise). I was in my 40s when teaching English Communication at that university - but my system of evaluation with variations also played out in a middle school of some prestige (one of my students was the daughter of the Minister for Education and Science - among other noted figures of the region) and at a senior high teaching university prep. stream classes. Bravo to Blake and Milligan and to you, NG.

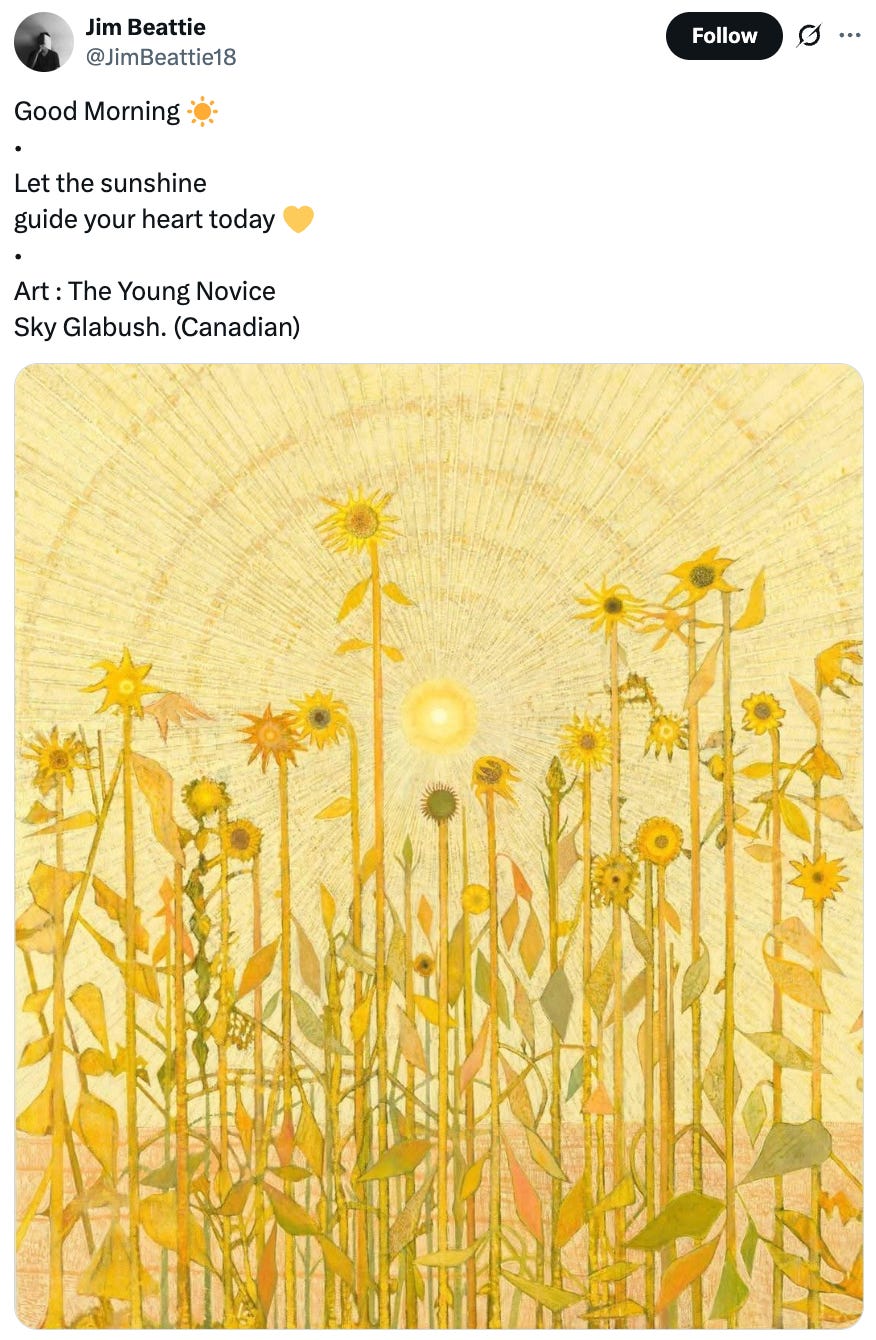

Thanks Jim