AI: is it coming for us? (No) Is it a big deal (Yes)

AI: is it coming for us? (No) Is it a big deal (Yes)

This is an excellent podcast featuring an ‘industry expert’ and then someone who’s introduced as an ‘economic genius’ — Tyler Cowan. The industry expert is good on salient facts to help you understand how we got to where we are now. American journalism seems to value this more than our own journalism which has a good deal more spin about it — and many more appearances on Insiders.

Meanwhile Tyler gives us his take on AI which is well worth listening to. He is indeed an amazing fellow. He runs his own podcast where he interviews people from a vast range of different backgrounds, casually demonstrating his own reading in the area. He seems to publish a book every year or other year. He runs a group blog, holds down an economics professorship and a Bloomberg column. And one of the books he published is on his own autism. You can notice it in his style. Anyway, it’s not surprising he’s so up on ChatGPT since he’s the nearest thing to ChatGPT team human has ever thrown together itself.

Naturally enough Tyler’s take is that AI could be a threat like any — he repeats “ANY” — important new technology but that it’s too early to regulate it — since we wouldn’t know how. And that in the meantime we should be excited about its ability to complement our own abilities.

Indeed, while teachers and lecturers around the world see AI as a threat to their ability to examine their students, Tyler's jumped out of the blocks in no time. Now of the three essays his students are assessed on, one examines them on their ability to use AI for research assistance and collaboration.

Which is cool.

Anyway, I recommend the podcast.

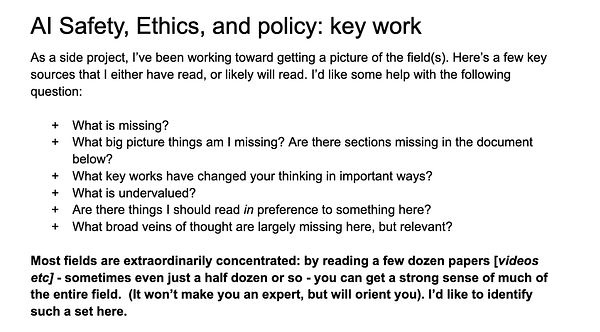

The latest, best reading on AI

Next Week’s Newsletter.

Substack offers a service whereby you can send your work in draft form to anyone you like. Because some subscribers do want to see what’s brewing, I’m giving you the link to next week’s substack as well. Of course it will start empty or with the overflow from this week, but will build over time. So if you want to space out your reading a little you can do that. Note, I do tend to tidy things up on Friday evening, so in addition to having less content, it’s rougher until that process takes place. That having been said, next week’s substack is growing on this link!

Eulogy for Keith Rule

Eulogies are some of the best speeches given. I’ve always thought it would be great to have a website dedicated to just that. There probably are such websites, but Speakola is a general website for great speeches and carries this eulogy by journalist Andrew Rule for his father. I’m guessing that Andrew is a few years older than me and it will bring back memories for anyone born before 1970. My dad was an Austrian professor and not much chop with an axe. But my mum always wanted to farm and so I grew up on a farm in the foothills of the Dandenongs. And the kind of person eulogised here was what the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre calls a ‘character’.

A character is an object of regard by the members of the culture generally or by some significant segment of them. He furnishes them with a cultural and moral ideal. Hence the demand is that in this type of case, role and personality be fused. Social type and psychological type are required to coincide. The charader morally legitimates a mode of social existence. … The Public School Headmaster in England and the Professor in Germany, to take only two examples, were not just social roles: they provided the moral focus for a whole cluster of attitudes and activities. They were able to discharge this function precisely because they incorporated moral and metaphysical theories and claims.

And the bushman with his craft, with his disdain for pretence, his decency and kindness (hiding behind that veneer of masculine toughness) was still alive when I was a kid. Today not so much. Today the character is often exploited by those who are trying to manipulate us — into buying margarine or sending troops off to someone else’s war.

The whole 53 minutes comprises an interview followed by the speech re-read by Andrew. I enjoyed the interview, but you can also just skip to the speech which begins at 32.20. It’s wonderful.

And here’s Andrew’s eulogy to his recently departed friend, Les Carlyon.

And while we’re speaking about endings …

Last week I found myself not at my desk, but in a rehearsal room … I was at a workshop rehearsal for the musical of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, and all I can say is that it was like watching the inside of my head grow shoots and leaves and suddenly burst into many-colored flowers. The story had regenerated itself without me. It is no wonder I was in awe.

The musical rehearsal is the latest in a succession of “other lives” for a one-off book I wrote over ten years ago, that was actually based on a radio play I had written five years before that. The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry is the story of an ordinary man who receives a letter out of the blue from his dying friend and makes an instinctive promise to walk the length of England in order to save her. It was my first novel and its success was not something I had ever anticipated.

Following that, came a second book, The Love Song of Miss Queenie Hennessy—the whole tale told, as it were, as a reverse shot, from the point of view of the woman for whom Harold is walking. And finally this year, there is Maureen, the story of the wife Harold left at home the day he set off on his walk.

Read on for a wonderful rendition of reality — the reality of fiction that rings true — opening up and growing shoots of new life for the author.

Modern morality tale: Rats discovers greed not all good: SHOCK!!

Do we really want to join a US v China war?

Geoff Miller thinks not.

We want the US to continue to play a major role in the Asia-Pacific, but there must be an appropriate place for China as well. As the former Secretary of DFAT, Peter Varghese, wrote in September last year: “If we tether ourselves to the cause of US primacy we leave ourselves exposed to US policies that may make sense for the US but not necessarily for Australia. We risk structuring our defence forces to fight alongside the US rather than primarily for the defence of Australia. We risk buying into a narrative of democracy versus autocracy which, however inspiring, misreads the strategic and historical drivers of China’s actions and has little resonance in our region.”

Australia, with its small and presently ill-equipped armed forces, could contribute almost nothing to a clash between the United States and China that has nothing to do with us. The US is such a large and globally important country that its relationships can in the end be repaired even with countries with which it has been in conflict. That does not apply to us, and if we joined the US in fighting China over Taiwan, not only would we not make any appreciable difference but our relationship with our biggest trading partner would be destroyed for years.

We should regard the Taiwan issue as one for us to “sit out”.

Philosophize this: Simone Weil

This is my favourite philosophy podcast. Often when they’re way over my head, Stephen West offers an interpretation of where various philosophers are coming from. They’re never dumbed down, yet they’re pretty easy to understand. And they’re usually funny as well. Anyway, here’s the first of four half-hour podcasts on Simone Weil, on the subject I know her for which is her philosophy of attention. Iris Murdoch was greatly taken by and influenced by it.

Here’s an anecdote West recounts from Simone de Beauvoir about a conversation she had with Weil.

There was a famine that happened in China in 1928. … Simone Weil… was COMPLETELY adamant in the conversation saying… that there is one thing that matters that we should all be FOCUSING on here…and that is the revolution that needs to happen… that is going to FEED all of the people around the world that are starving.

Now, Simone De Beauvoir, THINKING like an existentialist philosopher, you know future author of the second sex and the ethics of ambiguity…SHE hears this and says back to her, well look…the problem is not to make people happy, she said, the problem is to find a REASON for their existence.

At which point, apparently, Simone Weil takes a step back…looks Simone De Beauvoir up and down head to her feet and says, “it’s easy to see YOU’VE never gone hungry.”

And here’s the guts of this podcast’s presentation of Weil’s philosophy of attention, though I recommend your listen to it all.

There’s a middle path. Instead of no activity or over-aggressive activity…what Simone Weil calls a sort of NEGATIVE activity…where it’s not sitting around doing nothing, it’s not trying to FORCE things…when you walk this middle path you’re definitely PUTTING in effort…but it’s a different KIND of EFFORT…it’s an effort where you REMOVE something from your experience, you REMOVE BAGGAGE, you REMOVE your own personal prejudices that you’re bringing to things…she describes it at one point as:

"the effort which brings a soul to salvation is like the effort of looking or listening."

In other words it’s not SEARCHING…it’s more like WAITING. It’s not REASONING for hours coming to an abstract CONCLUSION about something….it’s more being open and, detached from your own selfishness long enough, to RECEIVE something, that the universe has YET to disclose to you.

One of my FAVORITE quotes from her that just EMBODIES the spirit she brought to every day of her life: “The great human error is to reason in place of finding out .”

More of the transcript here.

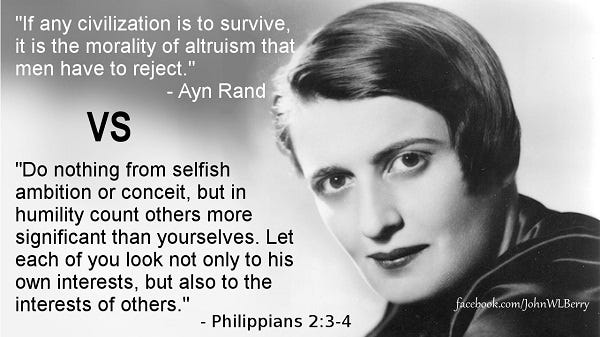

Ayn Rand: what all the fuss has been about

That’s what I’ve never been able to figure out — I still can’t. But in musing about this on Twitter Shane Easson sent me to this terrific 1957 Whittaker Chambers review Rand’s book Atlas Shrugged, which I will die not having read.

Since a great many of us dislike much that Miss Rand dislikes, quite as heartily as she does, many incline to take her at her word. It is the more persuasive, in some quarters, because the author deals wholly in the blackest blacks and the whitest whites. …

It is then, in the book’s last line, that a character traces in the air, “over the desolate earth,” the Sign of the Dollar, in lieu of the Sign of the Cross, and in token that a suitably prostrate mankind is at last ready, for its sins, to be redeemed from the related evils of religion and social reform (the “mysticism of mind” and the “mysticism of muscle”).

That Dollar Sign is not merely provocative, though we sense a sophomoric intent to raise the pious hair on susceptible heads. More importantly, it is meant to seal the fact that mankind is ready to submit abjectly to an elite of technocrats, and their accessories, in a New Order, enlightened and instructed by Miss Rand’s ideas that the good life is one which “has resolved personal worth into exchange value,” “has left no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ‘cash-payment.'” The author is explicit, in fact deafening, about these prerequisites. Lest you should be in any doubt after 1168 pages, she assures you with a final stamp of the foot in a postscript: “And I mean it.” But the words quoted above are those of Karl Marx. He, too, admired “naked self-interest” (in its time and place), and for much the same reasons as Miss Rand: because, he believed, it cleared away the cobwebs of religion and led to prodigies of industrial and cognate accomplishment.

Poking philosophical pretensions

I was reading a very heavy philosophical blog post when I came upon this comment alerting me to Jerry Fodor’s takedown of analytic philosophy. Reminded me of when I did history as an undergrad and the articles — even in learned journals could be very entertaining and full of classy jokes. This is not in an academic journal, but rather the London Review of Books, but it’s great fun, as well as lampooning

In 1953, W.V. Quine published an article called ‘Two Dogmas of Empiricism’. Easily the most influential paper of the generation, its reverberations continue to be felt whenever philosophers discuss the nature of their enterprise. In a nutshell, Quine argued that there is no (intelligible, unquestion-begging) distinction between ‘analytic’ (linguistic/conceptual) truth and truth about matters of fact (synthetic/contingent truth). In particular, there are no a priori, necessary propositions (except, perhaps, for those of logic and mathematics). Quine’s target was mainly the empiricist tradition in epistemology, but his conclusions were patently germane to the agenda of analytical philosophy. If there are no conceptual truths, there are no conceptual analyses either. If there are no conceptual analyses, analytic philosophers are in jeopardy of methodological unemployment.

Whether Quine was right remains the bone of vigorous philosophical contention to this day. In fact, despite their extensive influence, there isn’t any robust consensus as to what, exactly, the persuasive arguments in ‘Two Dogmas’ are or were supposed to be. (Philosophy is like that.) Suffice it that, since Quine, the practice of conceptual analysis has lacked a fully credible rationale. That’s not to say that anybody much stopped doing it. To the contrary, it’s often suggested that Quine must have been wrong because conceptual analysis is what analytic philosophers do, and there must be something that they’re doing when they do it. That put a brave face on it, but there were guilty consciences wherever you looked.

What wasn’t in Peter Jackson’s Beatles film, but should have been!

John Gray on Andrew Sullivan’s Dishcast

I recommend the first 15 or 20 minutes of this podcast. Defs worth the listen as John Gray explains where he comes from — literally and intellectually and ideologically. His milieu is British working class and he got to Oxford and has been a maverick to all classes ever since.

I loved his point about how rickets went down during World War II rationing in his hometown, a small, prosaic illustration of his point that, at any time a vast number of things are getting better at the worst of times, a vast number of things are getting better at the worst of times.

Then he and his host talk about how populism is the blowback from liberalism. An interesting thing to think about — I expect they’re right. But it’s all wrapped up in a morality tale about Hilary Clinton. Yes, Hilary Clinton was a shitty candidate and her candidature showed the way power trumps quality inside political parties, including progressive ones. But that’s a somewhat different morality tale. The Republicans were the neoliberals par excellence during the relevant period. You can blame the Democrats for not representing their own constituency better, but they did represent it better than the Republicans.

And then they talk about Brexit. John Gray was a Brexiter but of course not the Brexit we’ve ended up with. So like Dom Cummings, it’s OK to turn the place upside down, with a big red bus running up and down the country with a massive lie on its side, led by a sociopathic lair who was sacked for dishonesty from his first two jobs to ultimately massively disadvantage of those you claim to care about. Then you say ‘Oh well, it wasn’t what I voted for’. The Churchill defence for Gallipoli! As my Mum used to say “You dear old pet.”