This week’s newsletter. As you’ll read below, I sent this newsletter out early but this morning I’ve already had people asking “Where’s my newsletter”, so I’m sending it out again in case you missed it in your weekend’s reading.

The proprietor

An early newsletter

I just had too much material, so I’m sending this out now. With a bit of luck I may send out another one on Sunday — we’ll see.

Ideological surprises

I like surprises of the kind I reported in the tweet below.

AI and the burgeoning of bullshit:

Best essay I’ve read for a while

Starting with two mission statements, one by AI, the other by humans, Andrew Dean’s essay addresses the issues I’ve wanted to see addressed on the subject. Not when or whether AI will have a HAL moment “I’m sorry I can’t do that Dave”. And not how it will revolutionise white-collar work of many different kinds — which it will. But how it holds a mirror up to our own consciousness, our own entanglement in language and our increasing entanglement in bullshit.

One of the most important early archives for research into natural language processing was the Enron email corpus. After the US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission finished [with them] it decided that [they should] make the materials widely accessible online. The emails show that weeks before the company’s failure, executives were telling each other that the firm was not only in good shape but that it would break all profit expectations. These cheery despatches from the frictionless world of make-believe were structured in and by the language of corporate confidence. The communications are in that sense much more than lies: they are testaments to a language of pure fantasy. Truth departed the scene and executives limitlessly remixed each other’s stories. When reality eventually intruded on these witless leaders … the discourse collapsed. …

The 1.6 million emails have long been the dataset of choice for natural language processing projects. In other words, the most significant material on which natural language processing was based was the trail left behind from the largest bankruptcy in American corporate history at the time. Crucially, the archive is from the period leading up to the collapse. …

Where GPT3 is strongest is precisely in this realm of make-believe, where things cannot be tested or known. Think of it as a firm that is bankrupt and trading but that never collapses – Enron without the Wall Street Journal. [Derrida’s dictum] Il n’y a pas de hors-texte [‘there is nothing outside the text’], it turns out, is true not so much for literary writing and its interpretation, but for the forms of expression that were never more than synthetic in the first place. This is why large language models perform so much more believably when they attempt to pastiche university mission statements and other corporate dejecta than when they attempt to read poems. Such statements are already pastiches that cannot survive outside the entirely internal world of their own discourse. They can be mimicked effortlessly because they ultimately refer to no reality, to nothing concrete, nothing that is meaningfully there. It is language all the way down. In fact, that is their point.

How we all became competitors

In this episode of uncomfortable collisions with reality, Peyton and I talk to Jonathan Hearn who has just published "The Domestication of Competition" a history of the way in which competition became increasingly significant as modernity progressed. Increasingly competition came to be seen as a worthwhile way to distribute power, align interests and serve the common interest. This was true in politics as modern electoral democracy developed, in science, in business and of course in sport which became increasingly professionalized and commercialised.

And as competition grew in significance, more attention was paid to building the institutions necessary to compete and to govern that competition for the common good. In this discussion, we discuss his book and also explore differences in his own approach to these things as an historian, anthropologist and sociologist and my own as an economist interested in making our institutions work better. I'm particularly interested in the ways we could shape competition to improve its functioning in the social interest.

If you'd prefer to listen to the audio only, you can find the mp3 podcast here.

The contemporary relevance of Awakenings

I attended the first in-house screening of the new film Awakenings with the author of the book it was adapted from — Oliver Sacks — and perhaps a few dozen others. How did that happen. My cousin Lawrence was a Newyorker staff writer who was a good friend of Sacks, having taken a journalistic interest in him long before he became well known. He has also published this book on him — and see this review of the book in the NYT. I loved the story but hated the sentimentality with which it was told. I fancied Sacks thought so too but was too well-mannered to allow himself to express it, but I was probably just indulging a personal weakness (thinking I was right).

Anyway, this is quite an intriguing write up of the relevance of the book. I’m not sure I quite buy the usefulness of this bifurcation between ‘classical’ and ‘romantic’ science. The contrast is evident enough, but simply naming it and saying both types are complementary doesn’t help in crafting that complementarity. And so we’re left with dominance of rats and stats with occasional ‘dissenting’ or ‘humanist’ pieces which sell books but don’t change practice. (I wrote a piece on the strange way in which the placebo effect was rubbed out of medicine by clinical trials, and yet remains a well known and powerful theraputic agent which modern medicine seems sworn not to use for good.)

In his memoir, Luria expressed respect for both the classical and the romantic dispositions: “I have long puzzled over which of the two approaches, in principle, leads to a better understanding of living reality.” Sacks claimed to hold the same view: in a long footnote late in Awakenings he writes, “I should make it clear that my purpose is to distinguish two modes of clinical approach, and to indicate their complementarity — not to advocate either as against the other…. Thus our theme and plea relates to the complementarity of both approaches — the development of the technical without any forfeit of the human.” But this is largely window-dressing. Sacks clearly thought that the classical or technical model of medical science had become so overwhelmingly dominant that the human had indeed been forfeited and needed to be reclaimed. And the turn of Luria toward detailed narrative confirmed him in his own commitment to “romantic science.”

This turn was further confirmed for Sacks when he received a letter from Luria in July 1973:

I received Awakenings and have read it at once with great delight. I was ever conscious and sure that a good clinical description of cases plays a leading role in medicine, especially in Neurology & Psychiatry. Unfortunately, the ability to describe which was so common to the great Neurologists and Psychiatrists of the 19th century … was lost now, perhaps, because of the basic mistake, that mechanical & electrical devices can replace the study of personality.

The wages of vandalism

The case for price controls and windfall taxes

One measure of the success of a social movement is the extent to which it creates a ‘commonsense’ that even its ideological opponents get roped into. That was the great triumph of neoliberalism — bringing the moderate progressive left into its fold. In fact it was the left — fancying itself the less stupid party and full of people who think about policy — who were the original entrepreneurs of deregulation in Australia, New Zealand and even the US — Jimmy Carter set off a lot of deregulation in transport and some other stuff in infrastructure. (One can even include Jim Callighan’s Government in the UK if you include his now canonical proposition that you can’t spend your way out of a recession — which is wrong by the way, but in context it probably wasn’t.)

And before neoliberalism, it was Nixon who embraced the New Deal consensus — and helped extend it to the environment and who said “we’re all Keynesians now”. Anyway, remember how they hated profiteers and got into all kinds of government intervention including rationing in WWII. Well that made good economic sense. And some government intervention in the presence of commodity price spikes makes sense today. Such interventions include domestic price caps and windfall taxes.

In the piece below Isabella Webber explores the case. It’s a pity that these discussions don’t simultaneously discuss institutional developments that might make government intervention safer and more likely to be unwound through time. Even if one has established that they’re good policy, there remain good reasons for neoliberal hesitancy on price controls based on the prospect of those policies being deployed on behalf of powerful interests — or political expediency — rather than the public interest.

The kinds of institutions one needs, require some insulation of the policy from day-to-day politics. We’ve traditionally dealt with that with independent agencies — like the RBA and the ACCC, though I’m increasingly persuaded that citizens’ juries can more effectively internalise the issues and arrive at the right answers.

The history of price stabilization goes back centuries, from the mists of classical China (my own research focus) to the major crises of the past century: World War II, the Korean War, and the stagflation of the 1970s in the United States. In each case, price-stabilization policies served as emergency measures aimed not just at “fighting inflation,” but at doing so in a fair and socially stabilizing manner. Their primary purpose was to attack profiteering (from wars, famines, and disasters) head-on. They have tended to work in highly concentrated markets, and when implemented before inflation spirals out of control, while performing poorly otherwise. And when carried out in democratic societies, through a mobilization of the population behind a common project of price restraint, they have been massively popular – especially when weighed against the alternative of austerity.

But by late 2021, that history had dropped out of the common sense of economics.

In February 2022, my colleague, Sebastian Dullien, and I set out to establish that there are indeed feasible alternatives to macroeconomic tightening. We proposed a fiscally financed price cap on basic household consumption that would preserve market prices at the margins. This led to another round of criticism from economists. But our proposal also received strong endorsements from a wide range of interest groups.

Fast forward to September 2022, when I found myself appointed to a German government commission charged with designing a price-stabilization policy to address the energy crisis following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. There, we developed the so-called “gas-price brake,” and the key principles that I had been advocating were subsequently enshrined in German law.

Germany is not alone in implementing a price policy. Across Europe (and in the United Kingdom), governments have implemented various forms of price controls to contain the war’s fallout in global energy markets. The European Union has enacted a gas-price cap, the G7 has imposed a price ceiling on imported Russian oil, and the US government has leaned on the price of oil by releasing supply from its Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

Moreover, leading economists have rushed to endorse selective, targeted price controls. By January of this year, Paul Krugman of the New York Times, for example, was suggesting that it might not be so foolish after all to respond to price explosions with price policies, even though he had criticized this approach earlier.

I wrote this piece before I discovered that my normal subscription didn’t cover it — they wanted a ‘Premium’ contribution. I found a way to access it and reproduced the extract above, but just a warning. If you press the “More Here” button below, you may be able to read the rest of the piece, but save it because, if my experience is anything to go by, you’ll get locked out.

Contraception: is the Pope a Catholic?

In an interesting summary of the state of play in the Magic Kingdom, Peter Singer wonders.

Doubts about the permanence of the Church’s doctrine [on contraception, which goes back to Aquinas and beyond and was formalised by Pope VI] were raised last year, however, when the Pontifical Academy for Life released Etica Teologica della Vita (Theological Ethics of Life), a volume, in Italian, of more than 500 pages that brings together papers from a seminar along with the text that served as the basis for discussion. Some of the senior Catholic theologians contributing to the discussion suggest that the use of contraceptives in some circumstances may not be wrong.

Conservative Catholics gathered at a conference in Rome last December to respond to the publication. John Finnis, an emeritus professor of law and legal philosophy at the University of Oxford and a leading exponent of the natural-law approach to ethics, gave a talk entitled “The Infallibility of the Church’s Teaching on Contraception,” in which he argued not only for the title’s thesis, but also that defending it is “an inseparable and on the evidence irreversible element in adhering to the Catholic faith as true.” In other words, one ceases to adhere to the Catholic faith if one allows the doctrine even to be questioned.

Where does that leave Pope Francis? When asked by a journalist whether he was open to a reevaluation of Church doctrine regarding contraceptives, he replied that the question was “very timely.” And he implied that it would be wrong to forbid theologians from discussing any topic, because “you cannot do theology with a ‘no’ in front of it.” Referring specifically to the publication of Etica Teologica della Vita, he said: “Those who participated in this congress did their duty, because they have sought to move forward in doctrine.”

According to Finnis, the pope, it seems, is not Catholic. Nor are many others. According to a 2014 poll, over 90% of Catholics in countries including France, Brazil, Spain, Argentina, and Colombia favor the use of birth control, and a 2016 Pew Research Center survey indicates that even among Catholics who attend mass weekly, only 13% say that contraception is morally wrong. If Finnis is right, there are far fewer Catholics than most people think.

Meanwhile: somewhere that is not Florida

Why I like having remarkable friends

I get cool Christmas and New Year greetings like this one — which then go missing in the post, go back round the world several times and turn up “First Class Mail” from the States. The artist is mathematician, political theorist, and good friend Alex Coram

Albo room on the voice

From the almost always excellent Inside Story, this piece of analysis focuses on the issue du jour, namely whether the voice is to parliament or to parliament and the executive — including ministers and public servants.

Once the Voice is up and running, someone might conceivably bring an action in the High Court alleging that the executive failed to pay due attention to the Voice’s advice when it made a particular decision. The High Court might respond by setting out protocols obliging the executive to demonstrate that it really has taken account of the Voice’s advice. It could say, for example, that the executive is constitutionally obliged to publish reasons for not following the Voice’s published advice.

Some commentators see this as an appalling possibility, and it certainly provides a theme for those writing the official No case. They will present as an intolerable risk the possibility that a government will be obliged to demonstrate that it has really listened to the Voice’s advice. As Tony Abbott wrote recently, the possibility that such a Voice “would have to be listened to” is a reason to vote against the amendment. Craven has speculated that many voters are constitutional conservatives, fearful that future governments will be crippled by a new line of accountability.

This speaks to something I started to ponder a while back: of the three arms of government, only one is governed seriously by reason-giving. The legislature and the executive find themselves drawn into giving reasons. But they don’t have to be good ones. In some ways it would be less misleading to the public if they didn’t give reasons since they invariably contain some degree of misdirection. If you’ve got the numbers or hold the office and have the power, you can make the decision. In one sense it’s no different with the judiciary in that the numbers determine the decision. But judiciaries operate as a hierarchy of decisions supported by reasons. They’re the only branch of government in which reason giving is taken sufficiently seriously that a lower body can be overruled by a higher one in the same branch of government on the grounds that the higher body thinks it has better reasoning.

Be that as it may, as the author of this piece concludes, Albo’s taking the side of the Indigenous community creates risks and also great opportunities to do something we’ve needed to do since we flubbed the opportunity 230 years ago and put up a monument to Captain Cook instead. Some cross cultural listening. How likely is it really? In the light of our history, of the weaponisation of the language of identity politics and of how little our political system listens even to its own constituents? Not very, but then if you don’t try you don’t find out.

Filed under great predictions

How the subs tie us into China action

Hugh White is not a happy camper and with good reason. He explains how we won't get the subs outside of American confidence that we’re going in to Taiwan if needed.

Marles’ second answer is no doubt right. If and when the Virginia-class subs are in service with the Royal Australian Navy under Australian command, they will not go anywhere unless the Australian government sends them. That is our choice.

But that is not quite the point. The real question is how AUKUS affects that choice – the choice Australia would make about whether to join a war with China. And the answer is clear: AUKUS commits Australia to fight China if America does, simply because the AUKUS deal will be off if we don’t.

That is because America will only sell us Virginia-class boats if absolutely certain that those boats would join US operations in any war with China. They will come straight out of the US Navy’s order of battle, because no extra Virginia-class boats are to be built to meet Australian needs. So every boat that joins the RAN is one less in the US fleet, and the US Navy is already desperately short of submarines. It is simply inconceivable that Washington would agree to a significant diminution of its submarine capability in this way as its military rivalry with China escalates. …

Americans see this as a fundamental obligation of the alliance that we hold so dear and that we declare to be the very heart of our foreign and strategic policy. No one who was there will ever forget the way one of Washington’s most renowned figures, Richard Armitage, spelled this out in words of one syllable to an audience of prominent Australians almost 25 years ago.

So AUKUS is only going to work if the Albanese government plainly acknowledges Australia’s willingness to join America in a war with China. But that is a war that America has no clear way to win, and which may well become a nuclear war. That is one of the many reasons why AUKUS is a dumb idea. It also raises big questions about Australia’s whole approach to the US-China contest.

In case you’d not seen this

I mentioned it in this blogpost.

Taiwan: those were the days

And here is the anecdote about Richard Armitage in the item above. From the SMH 11 years ago:

In his blog, the former NSW premier Bob Carr declared that America's reaction to China ''displays all the neuroses of the world's most insecure empire, always imagining its enemies at work to bring it down''.

Carr recalled a session in 1999 of the Australian-American Leadership Dialogue, the closed-door private diplomatic initiative run by the then Melbourne businessman Phil Scanlan (now consult-general in New York).

Richard Armitage, later to be George Bush's deputy secretary of state, talked about the prospect of war over Taiwan and demanded to know what would be Australia's role.

''Are these people nuts?'' is how Carr remembers ''the whispered response of all the Australians''.

Hugh White, the Australian National University strategist who recently set off a resounding debate with his essay urging a US-China power sharing agreement, was another participant. At the time he was a deputy secretary in our Defence Department, engaged on writing the 2000 defence white paper for the Howard government.

White recalls giving the dialogue a rundown on Australia's defence planning, foreshadowing the white paper, and the following exchange.

''That's all very well, Hugh,'' Armitage cut in. ''But I really don't see the force structure you are developing giving you a lot of options to support us when the balloon goes up over Taiwan.''

''Well, Rich,'' White says he replied, ''you've got to understand that Australian defence policy is not based on the idea that we support the United States in those scenarios.''

''Well, they ought to be,'' Armitage declared. ''What do you think this alliance is about?''

White then went over the 1976 defence white paper and the review of defence force structure by the then deputy defence secretary, Paul Dibb, positioning Australia after the Vietnam War.

Armitage was not mollified. He recalled that Armitage ''in his inimitable way literally, not just metaphorically, thumped the table and said that in the event of a US-China conflict over Taiwan we'd expect Australia to be there''.

''And there was a lot of ambivalence in the room amongst the Australians as to whether we would or not,'' White said. ''That ambivalence included Coalition ministers.''

Indeed, five years later Alexander Downer suggested the ANZUS Treaty did not oblige Australia to help defend Taiwan. He was rebuked by his prime minister, John Howard, and Australia went back on the fence.

Marshall McLuhan: the global village is no picnic

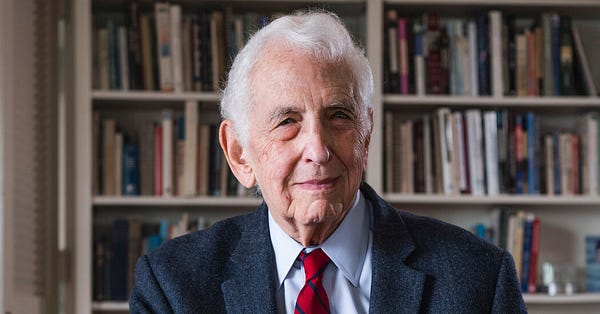

Interview with Daniel Ellsberg

When I think of my own life compared with my kids I can think of two huge differences. When I went house hunting houses cost around 3 times annual earnings. Today they cost closer to 7 times. And that’s both a cause and consequence of a returning Edwardian class structure. (In fact, there were three classes on ships in those days — first, second and steerage. Today there are four in big jets. First, business, premium economy and economy.) Most upper middle class kids have a nanny. And so on.

The other difference is that Daniel Ellsberg was prosecuted under the Espionage Act and the case was thrown out for government misconduct. Today Edward Snowdon sits in exile in Russia and Julian Assange sits in jail awaiting extradition.

Below are brief tweet-length extracts from an interview with the 91 year old, terminally ill Ellsberg each one of which has the link to the original NYT article.

Stay or leave when your country is going toxic

As a state, Israel has borne contradictions and inconsistencies since its inception. But these have always been accompanied, at the highest and lowest levels of society, by values and ideals that many believed would eventually bring freedom and peace to the inhabitants of this land and their neighbors. This was, at least, the Israel into which I felt I was born. But nothing remains as it was. The politics of the Middle East changed, and the vision of two states for two peoples was increasingly eclipsed by extremism and terror on both sides. Demographic changes within Israel also changed its social fabric and did not bode well for those of us who are freethinking. The values of liberalism and pluralism belonged to a section of society that was quickly becoming a minority. The rising majority simply did not share these values. At bottom, they did not believe in modern democracy as a governing system, and no democracy can keep itself afloat without the faith and commitment of its people. Simply put, the country no longer had a liberal democratic majority. This has been the case for some time and, in such a state of affairs, the end of democratic rule is all but inevitable. The real question is what comes next—and what do people like me do when it arrives.

It is really an age-old question: When things turn dark in your country, do you resist from within or go into exile? The question was asked too many times by too many people during the last century. It was posed not just by those in immediate danger but also those who simply want to live without fear. As someone who has already gone through an immigration, I know that moving is no picnic. The loss of identity, a sense of belonging, a feeling of elemental connection to your surroundings—losing all this can feel like death, bringing on a period of mourning from which not everyone emerges. That said, staying put increasingly becomes a nightmarish option, a dark fantasy that is quickly turning into reality.

To be clear, I don’t think the Israeli people are wholly to blame for the situation in which we find ourselves. Nor are we completely innocent. Ours is a geopolitical situation that has eluded peaceful resolution for nearly eight decades. But the fact is that we are at a frightening crossroads in which the character of our country is revealing itself in a way that many who live here never thought possible.

A Pragmatic Foreign Policy Would Have Black American Support

Intriguing article by an interesting foreign policy guy Van Jackson. As he argues

The idea that the public—in whole or in part—is fit to judge foreign policy is alien to Washington.

By tradition, foreign policy is both an elite and elitist activity. The business of national security and diplomacy involves short reaction times, state secrets, bourgeoise social networks, and growing planetary complexity—all of which lends itself to elitism and technocracy. Foreign policy practitioners have long since taken a Lippmann-esque turn away from any conception of participatory democracy in foreign policy in favor an elite stewardship model that disavows the existence of a public mind or public will.

When I worked as a foreign policy practitioner, I recall having a haughty, dismissive attitude toward the public—much like my peers and superiors. I’ve since struggled with the problematic of how to do foreign policy in a way that makes it more participatory beyond just greater diversity in the diplomatic corps.

As the United States retools its economy and military to combat Russia, contain China, and prolong US global primacy, we find ourselves in another moment when US foreign policy is structuring the reality that the rest of us have to live within. One of several aspects that troubles me about all this “great-power competition” stuff is that it has proceeded entirely as a Washington-elite project. It has not answered to the public—to say nothing of the Black community—in any meaningful way. …

I have a hunch that Black Americans have a comparatively good bullshit detector about statecraft. … So at the risk of oversimplifying, the Black community would have counseled in favor of World War II, against Vietnam, and against both Iraq and the War on Terror. Sounds like good judgment to me.

The strange trajectory of critical theory

Here at the egghead end of the newsletter is a heavy essay on critical theory which, so far as I understood it, I liked. Then again I am sufficiently uninformed that I may have liked it mainly because it confirmed my own prejudices. They are:

First: that I don’t understand Adorno and Horkheimer and will almost certainly die not having put too much effort into remedying the situation.

Second: I like Marcuse’s elan — his ability to ‘put himself about’ to good effect in the 1960s. Or I begin by liking Marcuse until I think about the audacity of his claims and the insufficiency of his method for justifying such audacity. Viz:

Reading Marcuse today, one can still feel residual shivers from that great thrill of utopian moral certainty that brought so many young people into the streets in the sixties. To understand just how morally certain Marcuse and his movement were, it is enough to read his “Repressive Tolerance,” a text that anticipates with amazing precision the turn against free speech that many interpreters link to “critical theory” in its twenty-first-century version. “Repressive Tolerance” builds on the Frankfurt School theme of the half-glimpsed society of liberation blocked and concealed by the psychic distortions of the society of repression. Marcuse argues that in a society of “concentrat[ed] economic and political power,” the free and generative exchange of differing views envisioned by the likes of John Stuart Mill is simply not possible: “The decision between opposed opinions has been made before the presentation and discussion get under way—made, not by a conspiracy or a sponsor or a publisher, not by any dictatorship, but rather by the ‘normal course of events,’ which is the course of administered events, and by the mentality shaped in this course.” Because the game is rigged in favor of the existing power structure, and because the partisans of “progress” can be sure that the views thus repressed are in fact true and correct, it is permissible and even necessary for them to use every lever at their disposal to obstruct the forces of “regression,” including such “apparently undemocratic means” as “the withdrawal of toleration of speech and assembly” from groups that oppose the program of the New Left.

Three: it confirmed my dislike of Foucault:

Of course, Foucault’s accounts of power as “employed and exercised through a netlike organization” and of individuals as “always in the position of simultaneously undergoing and exercising this power” departed from the Frankfurt School accounts, which tended in the end to suggest—even if only rhetorically—a picture of a semicentralized repressive apparatus. And because he surpassed even the Frankfurt School theorists in his characterization of power as diffuse, subtle, embedded in the most unexamined and implicit forms of organization, Foucault was also less willing than they were to point beyond deconstructive critique toward what Marcuse called “the chance of the alternatives.” In his 1971 debate with Noam Chomsky, whose moral confidence brought Foucault’s political ambivalence into sharp relief, Foucault declared himself “much less advanced [than Chomsky] in my way…I admit to not being able to define, nor for even stronger reasons to propose, an ideal social model for the functioning of our scientific or technological society.” Instead, he said, “the real political task in a society such as ours is to criticize the workings of institutions, which appear to be both neutral and independent; to criticize and attack them in such a manner that the political violence which has always exercised itself obscurely through them will be unmasked, so that one can fight against them.”

Four: and my sympathy with the mildness of Habermas as the heir to critical theory, though, to adapt a joke from Fred Dagg, Habermas seems to be experimenting with the thickness of his books and the length at which he can say things that could be said simply.