It’s proving hard to manage the overflow. I toyed with sending something out on Mondays as well as Saturdays. Now I’m gonna send updates out when they’re kind of full. As this one is. I hope to get you something more at the usual time on Saturday.

Aboriginal domestic violence

The dispossession of Australia’s Indigenes was Australia’s First Great Crime. Our current Great Crime is the military-grade ring-fencing of the discussion so that Indigenous suffering can only be discussed in terms of non-Indigenous failings. It is obvious that the most important determinant of Indigenous wellbeing is what goes on in Indigenous communities. To say so shouldn't be controversial. Nor should it be taken to imply that ‘we’ — non-Indigenous people — aren’t implicated in the problem or that we shouldn't or can’t try harder. (We could start by caring whether current interventions — costing tens of billions of dollars — work or not.)

That all this is effectively off-limits to anyone but the confident right condemns us to impotence in tackling Indigenous suffering. But, as Iris Murdoch put it, the fat relentless ego won’t let us believe that it isn’t really about us. Except for those who are being brutalised right now, we wouldn’t want to discomfort anyone. We wouldn’t want the word getting out that any number of ‘reconciliation action plans’ in the non-Indigenous community won't address — can’t address — the problem.

Diane McDonald

I became aware of Diane McDonald’s beautiful painting when Danny Finley, a friend of ours sent my wife a link to her Facebook page. The bottom-most painting was a finalist in this year’s Glover Prize.

But the reason Danny told us about Diane was that she had died. How terrible. And there they are. Beautiful paintings she left us with. Her website shows you how endlessly she turned these out. Just lovely.

Gone with the Wind: American microcosm

Well this gets the gong for the best opening paragraph for the week, the month, and as far as I can remember the year! The rest of the article? It’s good too. Defs worth a read.

The night before Gone with the Wind’s Atlanta premiere in 1939, there was a ball at a plantation. Dressed as slaves, the children of the black Ebenezer Baptist Church choir performed for an all-white audience. They sang ‘There’s Plenty of Good Room in Heaven’; the actress playing Belle Watling, Rhett Butler’s tart with a heart, wept. The scene is already striking: a painfully literal example of the mythologising of the South for white consumption, redefining slavery as harmless and the slaves themselves as grateful. Yet Sarah Churchwell finds a jaw-dropping detail: ‘One of the little Black children dressed as a slave and bringing a sentimental tear to white America’s eye was a ten-year-old boy named Martin Luther King, Jr …

If the idea that one book and film can be the skeleton key to a whole culture seems simplistic, Churchwell swiftly begins to pile up startling evidence in short, pithy chapters. Race, gender, the Lost Cause, the American Dream, blood-and-soil fascism, the prison-industrial complex, a Trumpist mob storming the Capitol in 2021: it’s all here, and it’s all bound up with the themes of Gone with the Wind. Mythmaking is not just the building of fantasies but also the erasure of truth. The genocide of native peoples, for instance, is not in the book or film, but it was taking place at just the time that Gerald O’Hara would have been acquiring land in Georgia: ‘Scarlett’s beloved Tara is built upon land that was stolen from indigenous Americans a mere decade before her birth.’ Churchwell cuts through these thorny subjects with a propulsive assurance. Her writing is an extraordinary blend of wit, intellectual agility and forcefulness: it’s like being swept along by an extremely smart bulldozer.

Universal basic income: notes of an agnostic

Me at Troppo

Both on the right and left, most people arguing for a UBI have accepted that it would come with costs. Those costs include

less targeting leading to higher rates of taxation

removing the need to ‘work’. This will be a boon to many and to the extent to which it is, to society. But it will also shear away the incentive to work which is, in the minds of many, a foundation of the social contract and the quid pro quo for community support to the destitute. The hoi polloi are highly suspicious of doing away with this foundation, both in terms of its economic efficacy and its social ethics. This is relevant to:

the economics of how a UBI will turn out — considered broadly — whether it raises or lowers wellbeing (considered broadly) in the long run. I have at least as much respect for the hoi polloi’s suspicions of it underwriting an indolent underclass as I have for my own more optimistic view. I don’t know.

the politics of a UBI, both as to its long-term sustainability and the rate at which it’s paid.

So I remain agnostic

I’ve made these points previously. But they never turn up as central to your thinking about UBI. You’re an advocate for UBI and you’ve made up your mind. That’s your prerogative and it’s good that we have advocates in the community arguing for different things I guess. But with your stuff and with most of the other stuff I see advocating a UBI, it simply elides the central issues I’ve outlined above.

Albanese: his part in our sleepwalking

The indefatigable, dyspeptic national treasure Brian Toohey isn’t impressed with our foreign policy on the Great Issue of our Time — the rise of China. Nor is Hugh White whose (so far) excellent book Sleepwalking to War I’m reading right now. I’m not sure I’d have said as Brian does, that China might democratise. Of course, anything’s possible, but it’s likely to distract us from the discomfort of the choices before us (See Mitt Romney below!). Apart from that, I remain as mystified as he is by our servile masochism towards great, declining and unreliable friends:

Although the text of AUKUS has not been released, it states the US and UK are prepared to sell nuclear submarines to Australia. They would’ve done that without AUKUS. They would also have done so for other countries such as Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and Singapore, but they see more advantages in writing operating modern conventionally powered ones. NATO members without nuclear subs could buy them, but don’t because it doesn’t make military or financial sense. Yet Labor still wants buy eight nuclear subs, almost certainly from the US, so it can fire cruise missiles from nuclear submarines operating far from Australia into China. This is an extremely bad idea on both strategic and cost grounds. It will only provoke China which çan fire more missiles into Australia than Australia can fire into it. We could do more to defend Australia from closer to home with a mix of weapons at a much lower cost.

Mitt Romney joins the Alt-Centre: SHOCK!

Mitt Romney, one of the few remaining Republicans who is not insane or pretending to be (perhaps Mormonism works a little like homeopathy here!) has just joined the Alt-centre.

What accounts for the blithe dismissal of potentially cataclysmic threats? The left thinks the right is at fault for ignoring climate change and the attacks on our political system. The right thinks the left is the problem for ignoring illegal immigration and the national debt. But wishful thinking happens across the political spectrum. More and more, we are a nation in denial.

I have witnessed time and again—in myself and in others—a powerful impulse to believe what we hope to be the case. We don’t need to cut back on watering, because the drought is just part of a cycle that will reverse. With economic growth, the debt will take care of itself. January 6 was a false-flag operation. A classic example of denial comes from Donald Trump: “I won in a landslide.” Perhaps this is a branch of the same delusion that leads people to feed money into slot machines: Because I really want to win, I believe that I will win.

Fruitcake watch …

I Was Betrayed by President Trump

From one of the security guards on Jan 6th

Before Mr. Trump addressed his supporters on the Ellipse, he was told that those who were armed weren’t being let through security checkpoints and, according to Ms. Hutchinson’s testimony, he said, “I don’t effing care that they have weapons. They’re not here to hurt me.”

The nine people who died as a result of that horrific day — including the four officers who died by suicide after the attack — weren’t so lucky. Neither was I. I was attempting to hold a tactical police line as we were taught at the academy, to keep the invaders at bay. We were savagely beaten and easily overpowered. It was like a medieval battleground. … Over the course of the five-hour struggle, my hands were bloodied from being smashed by a stolen police baton. My right foot and left shoulder were so damaged that I needed multiple surgeries to repair them. My head was hit with such force with a pipe that I no doubt would have sustained brain damage if not for my helmet.

I have spent a year and a half in physical therapy for chronic pain that I have been told will never go away. My young son almost lost his father and my wife had to quit medical school, owing to the stress and demands of my ongoing recovery.

Polgar and my YouTube algorithm

I showed you a video of Judit Polgar beating Magnus Carlsen in the last newsletter. Whereupon, YouTube being YouTube, I was #PolgarBombed. The TED talk above came up — entertaining, intriguing, and moving. She’s also charming in this interview. And Gary Kasparov hogs the limelight in this clip.

The price of low interest rates

A review of The Price of Time by Edward Chancellor by my friend Felix Martin — though I’m not sure the Manichean treatment in the original book is very enlightening. The justification for going to zero interest rates was always that the alternatives were worse. That’s how I’d like to see the choices argued out, not as a battle between two Platonic forms.

“The Price of Time” addresses the biggest economic question of the past 15 years. Have the experimental monetary policies pursued by the world’s leading central banks since the financial crisis of 2007 and 2008 been a miracle cure or an epochal mistake? … Chancellor frames the fundamental issues at stake using a famous debate, conducted in 1849, between two members of the French National Assembly over what kind of monetary policy would best serve the new democratic ideals of the previous year’s revolution.

On one side was the radical anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. He argued that charging interest on capital retards investment, reduces employment, and is socially unjust. … On the other side of the argument was Frédéric Bastiat, France’s leading advocate of liberal capitalism. Positive interest rates, he insisted, are essential to the health of the financial system. Without them, lending would dry up and growth grind to a halt. The “propaganda of free credit”, he countered, “is a calamity for the working classes”.

For the next century and a half Bastiat’s view prevailed. But after 2008, a miraculous conversion occurred. One by one, the world’s leading central banks dropped their policy rates to zero – and in some cases below. By 2020, bonds worth more than $18 trillion were trading at negative yields. In Denmark, homebuyers were being paid to take out mortgages. Proudhon’s anarchist theory of interest finally got its day in the sun.

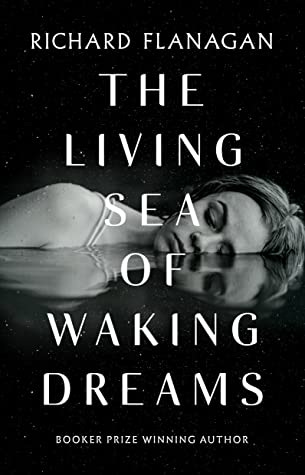

The Living Sea of Waking Dreams

I discovered this review trying to find the email address of the author, Graeme Garrett to send him a personal message (I don’t know if I got the right one, so if you know his email please pass this on to him). To my shame, I don’t read a lot of fiction and, given that, I’d not given much attention to Richard Flannigan because I’d associated him with the pearl clutching classes to whom he seems to be a favourite. But the review suggests that Flannigan is writing about the great transformations that are engulfing us. I enjoyed the review.

Central to Flanagan’s concern is what he calls “the vanishing”. In the human realm, this manifests as a “silent leprosy” (p.47) in which parts that belong to the human body – Anna’s mainly – suddenly aren’t there anymore. Anna first notices that the fourth finger on one hand is missing. This is followed by a knee, another finger, a breast and an eye. The worst of it is that by and large nobody notices, not even medical practitioners. Anna herself is strangely indifferent. “The only surprise for her was how little she felt about feeling so little” (p.151). Beneath this human apathy to human deconstruction, overheated Tasmania drives the vanishing ever faster and wider. “The ladybirds gone soldier beetles bluebottles gone earwigs you never saw now gone … flying ant swarms gone frog call in spring cicada drone in summer gone … and all around them the quolls potoroos swift parrots going going going” (pp.6-7). On a Hobart tram, nobody takes any notice. All are staring at their phones, searching, liking, friending, commenting, emojiing, cancelling, swiping, scrolling. “Thinking they were no more than writing and rewriting their own worlds, while all the time … they were themselves being slowly rewritten into a wholly new kind of human being” (p.224). …

It’s not flattering. But neither is it judgmental, cruel or cynical. The Living Sea of Waking Dreams is a lament arising from love of the Earth and passionate hope for the future of our human place within it. It ends with a gesture of adoration for “that immense gift, the intense gratitude” (pp.282) that wait to be called forth from our souls by the beauty and generosity of the earth around and within us. The meaning of this gesture and its entanglement in the lives of Francie’s children is an adventure that awaits your reading of the text.

I thought I might like to listen to it on Audible, but had to agree with quite a few of the reviews that the reading is more than I could bear!

Government 2.0: where is it?

All good - but especially the Tunzelman review and Brian Toohey - plus the piece on your father! Thanks!