Filed under “Never let a good deed go unpunished”

I’ve spent the last few years of my life pointing out that, around the world, there’s a general story about innovation in social services that goes like this. Entrepreneurial not-for-profits pioneer new, better ways of doing things, governments will notice and scale up “what works”. But … well, the innovations are there in pretty much every country; enterprising people are doing an amazing job on the periphery of the system in every country on Earth. And guess what? I have an open challenge out there to name a single social program that’s gone mainstream, or been ‘scaled up’ — as we like to say as we ape our Silicon Valley overlords — from some small neighbourhood program. That’s anywhere in the world. Actually, you could argue that Buurtzorg Nederland fits the bill. But that’s one in a generation. Can someone make it two?

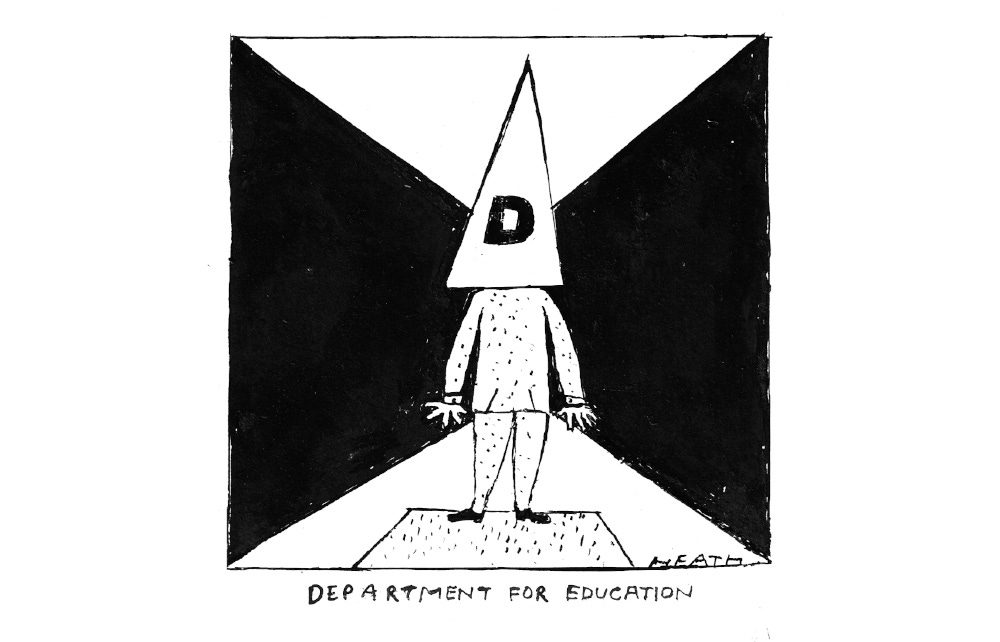

I discussed this with Chris Vanstone from The Australian Centre for Social Innovation (TACSI) here, in case you’re interested. In the meantime, the FT columnist extraordinaire, the inimitable Lucy Kellaway, started a not-for-profit to recruit long-in-the-tooth professionals to teach in morale-strapped, cash-strapped, teacher-strapped schools. It was a huge success. So it’s being defunded. Why, do you ask?

This makes no sense at all. The government is in the middle of a teacher recruitment crisis and so to scrap a scheme that beats its targets in bringing great new people into schools is madness. …

In secondary schools, the government last year only recruited half the number of teachers it needed and fewer still in STEM, where Now Teach is strongest. This means that vital subjects like maths, physics and computer science are routinely being taught by any old randomer who happens to have a free period. …

Now Teach is a small part of the answer to teacher shortage. We are aimed at older people, which is the only group of trainee teachers that is growing. While the numbers of university leavers wanting to teach are shrinking, fifty somethings joining the profession this year are up by a third. …

I expected an outpouring of angst on social media from Now Teachers. ‘Bonkers news,’ wrote one of our best maths teachers. He said if it wasn’t for the article he’d read in the FT in 2016 calling for people to join me in the classroom, he would still be working in the City. ‘That’s 850 students I would not have taught over the last seven years. What a disgrace.’

What I did not expect were protests from students themselves. On LinkedIn, one who was taught by a Now Teacher at a school in east London wrote how much she’d benefited from the experience. She has turned into the sort of student Rishi Sunak would love: she’s doing a PhD in maths.

The government has answered our outrage by saying that it values career-changers and will take over the mantle of doing the recruitment itself in future. [LoL. Ed.]

I’d like to see it try. … We know that the promise of our network and support draws people in. One of the Now Teachers who joined at the same time as me said the last time she’d felt part of a gang was 30 years earlier, when she’d been at university. It felt that way for me, too. …

The latest figures show Now Teachers are 20 per cent more likely to stick with it than older trainees who go it alone. Part of the secret is the network, but it’s also that we’ve learnt how to deal with the inevitable wobbles that go with such a bracing shift in career. One Now Teacher who has recently been promoted to head of sixth form at her school posted online: ‘I definitely wouldn’t have stayed without Now Teach. I wept my way through the first year.’

Last Monday, the schools minister was asked by the Lib Dems what on earth he was doing in cutting our money. By way of an answer, Damian Hinds pointed out that we’re a small organisation – last year we recruited only 250 people. That simply won’t do. For a start, our influence goes far beyond head count. And second, we are growing and would like the chance to grow more. But since his own longevity may be limited, perhaps that doesn’t interest him.

Shirley Hazzard and Elizabeth Harrower

Fascinating — and sad — segment from the little wireless program.

A moral panic we can believe in

Effective Altruism

Lots of people have a complicated relationship with EA. Like me. I tried to say something about this in a discussion forum I’m part of with the author of this piece.

Having now read it, I liked it and (to paraphrase my favourite comedian, Stewart Lee, I agreed the fuck out of it). However I hanker for someone to take me as concisely and as powerfully as possible through the process whereby EA instrumentalises — or perhaps the right term is ‘objectifies’ or ‘managerialises’ ethics. I’d love to do it myself of course, but I haven’t and I’m sure it could be done better than I could do it.

I was interested to read the German philosopher you quoted, but somehow it made what you were writing a little more derivative.

There’s something else that occurs to me as I write this which is that with EA — and positivism generally — their philosophical underpinnings are obsessively oriented around the obvious. In this case that

1) If you’re trying to do good, you should do as much as you can as effectively and efficiently as you can.

2) that whether or not one posits everyone weighing exactly equally in our moral thinking, moral questions can be expressed in equations. Total G = xG + yG. (Total good equals everyone’s good all added up.)

Broadly speaking, these conclusions are unarguable. I accept them, not just intellectually, but in my practical life. To borrow from an old economist, Alfred Marshall I try to have a warm heart and a cool head.

Yet I have to say that this kind of thing being paraded as deep thought both bores me and makes me suspicious that I’m really dealing with serious thinkers — for all their academic credentials. Like interminable books on leadership, particularly business leadership, there are a few precepts, and the rest is repetition.

And there’s an irony because, as EA demonstrates so amply, in pursuing obvious premises, they end up in some very strange and unobvious places — that in our widening circle of concern, we should turn our hearts, minds and scarce resources to the gazillion beings in centuries to come that will be affected by human extinction (even if our understanding of the future world we’re trying to improve, is infinitesimal).

Pandas coming to San Francisco Zoo

Pandas are coming to San Francisco Zoo, and who better to design the posters than my friend YiYing!

A glass half empty of biases, half full of intuition

Gary Klein on his ‘adversarial collaboration’ with Daniel Kahneman

Nice appreciation of the late Danny Kahneman by his friend Gary Klein who was in the rival camp of those who studied human decision making. I favour Klein’s side, but Kahneman impressed the folks in Stockholm more. I liked the article below, but it led me to check out the paper Kahneman and Klein produced. I like the idea of adversarial collaboration, but found theirs a bit underwhelming. You can check it out here should you wish.

On April 13, 2024, I visited the Stewart Building in New York for the last time. This was the home of Danny Kahneman. I had been visiting him there in his apartment for more than 15 years. Our collaboration goes back even further. … Danny died on March 27. … Many of the guests belonged to the heuristics and biases community that Danny and Amos Tversky initiated with their research in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

I was an outlier at this gathering. I am a critic of the heuristics and biases approach. My own community of naturalistic decision-making studies expertise instead of trying to debunk it. It does research with experienced decision-makers in real-world settings as opposed to college students performing artificial tasks in controlled environments, and it admires intuition rather than denigrating it.

Those were the reasons Danny invited me to join him in an adversarial collaboration, one of several he engaged in. Because we were adversaries, Danny wanted to see what we could discover. Danny disliked what he called the “angry science” of rivals trying to disqualify each other’s views. He thought adversarial collaborations offered a positive and productive alternative.

Our active collaboration lasted about six years and culminated in a paper, Conditions for Intuitive Expertise: A Failure to Disagree [Downloadable for a limited time from this link. Ed]. Danny has referred to our work as "my most satisfying experience of adversarial collaboration” (Kahneman, 2022).

At first, Danny and I each tried to persuade each other, but we quickly realized that our attempts would be fruitless and counterproductive. So, we accepted our differences and moved on together. Danny pushed hard for the subtitle of our article, “a failure to disagree,” which is somewhat misleading because we disagreed all the time. But we also converged on a set of criteria for gaining intuitive expertise: a regular situation as opposed to a chaotic and hypercomplex situation, the opportunity for practice accompanied by accurate and timely feedback on the consequences of decisions.

At the end of the collaboration, as we put the final touches on our article, we acknowledged that Danny liked stories about the mistakes experts make, and that I liked stories about the insights that experts provide. Despite my discomfort with what I perceive as the misuse of the concept of biases, I have suggested that the heuristics and biases movement has identified a number of cognitive tendencies—heuristics—that generally are valuable. We would be hamstrung without these, which I have called “positive heuristics.” I am disappointed that the heuristics and biases community has focused so heavily on the disadvantages of heuristics and has given so little attention to their benefits. …

In reflecting on what I have gained from our friendship and collaboration, I am struck by the ways that Danny has inspired me. I am inspired by the whole process of adversarial collaboration. In contrast to Socrates's enduring influence—he attempted to demean and expose his debate adversaries—Danny took the opposite stance, a generous stance of trying to learn and make discoveries together. For me, Danny is a far superior role model for philosophical debate than Socrates. [I agree with Christopher Fear that this is a pretty ungenerous reading of Plato’s dialogues — as explained in this paper.]

I am certainly inspired by the brilliance of his research, especially his collaboration with Amos Tversky. I am inspired by Danny’s pivots—especially the way it took up other topics, such as the basis of happiness, rather than continuing to investigate heuristics and biases. I am inspired by the spirit of our debates. He showed how to disagree without being disagreeable.

I am inspired by his fairness. When he revised a draft of our paper, if he made any change that he thought I might have misgivings about, he let me know about it. He never tried to smuggle any ideas or even implications past me.

I am inspired by his curiosity. He was certainly inclined to be skeptical about the existence of intuitive expertise, but then he started wondering if there were conditions that allowed intuitive expertise to develop. He followed his curiosity rather than his predilections. …

I am inspired by his humility. He was a Nobel Prize winner, but he never pulled rank. Quality of ideas and force of logic were all that mattered. It was a privilege to know Danny, work with him, argue with him, and be inspired by him.

Who’s afraid of Christopher Fear

Eristical versus dialectical discussion

Klein verballing Plato’s Socrates in the passage above leads me to extract this discussion by Christopher Fear under the uninviting title of “The philosophy of philosophy”. Actually, there were all kinds of problems getting the text out of the pdf, so I went to the philosopher Fear was elaborating — R. G. Collingwood and his New Leviathan which presented other problems. So I asked ChatGPT to step into the breach.

In his essay "The Philosophy of Philosophy," Christopher Fear argues that Socrates' method of argumentation was fundamentally dialectical rather than eristical. Here’s the gist of his argument:

Definition of Terms:

Dialectical Method: This is a form of dialogue between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject, who wish to establish the truth through reasoned argumentation. It is collaborative and seeks to uncover deeper understanding or truth.

Eristical Method: This method, in contrast, is based on disputing and is aimed at winning the argument rather than discovering truth. It often involves sophistry and rhetorical tactics that are not genuinely aimed at truth.

Socrates' Approach:

Fear argues that Socrates' approach in his dialogues is characterized by questioning and critically examining the definitions and beliefs of his interlocutors. Socrates' aim is not to win an argument but to probe and clarify concepts and beliefs, fostering a deeper understanding and insight among those involved in the dialogue.

Socrates frequently employs the method of elenchus, or refutation, where he tests the consistency and logic of his interlocutors' views. This method is inherently collaborative and constructive, even if it can appear confrontational due to its rigorous questioning style.

Philosophical Intent:

According to Fear, the essence of Socrates' method is philosophical rather than competitive. Socrates is more concerned with moral and existential truths rather than merely defeating someone in debate.

Socrates’ dialogues typically do not end with a clear winner or definitive answer, but rather with a deeper understanding of the complexity of the issues discussed. This outcome underscores the dialectical nature of his approach, where the process of questioning and dialogue itself is valued as much as any conclusions reached.

Educational Aspect:

Socrates' method also has a distinctly educational aspect; it is designed to help others think critically and deeply about important questions. This pedagogical dimension is more aligned with dialectical methods than with eristical methods.

Fear's analysis thus positions Socrates' philosophy as fundamentally geared towards enlightenment and understanding through dialectical engagement, rather than through adversarial debate or rhetorical victory. This interpretation aligns with the broader view of Socrates as a philosopher deeply concerned with ethical living and the pursuit of wisdom.

Café Sheherazzade

I remember occasional trips to Café Scheherazade with my Dad when I was a kid, but when I moved back to Melbourne in the 1990s I’m glad to say I managed to take my family to it once or twice. It was a time capsule of the refugee experience my father partook of in in the 1950s, but it also reminded me of similar non-’ethnic’ cafés of the time. You got a slice of white Tip-Top bread and a pat of butter wrapped in foil. Anyway, all things must pass, as has Café Scheherazade. Except in books such as the one I ran into in Readings a week or so ago.

In 1957, Anita Frydman acquired O'Hare's milk bar at Number 99 and turned it into a café. She sold it on to her husband's sister, Masha Zeleznikov, who, with her husband Avram, renamed it Scheherazade after the Paris café where they were reunited after terrifying Resistance activities during and after World War II. Avram, Masha and their families were involved in revolutionary move- ments in Poland, the Ukraine and Lithuania during the first half of the twentieth century. Their stories are told by Arnold Zable in his book Cafe Scheherazade.

Scheherazade was a cafe serving comforting Eastern European Jewish fare from family recipes. It was a haven, where for the price of a coffee, customers could sit for hours. Initially, it served as the gathering place of single men living in St Kilda boarding houses or one-bedroom flats, who had lost entire families in the Holocaust and had come to Melbourne as refugees.

Yiddish, Polish, Russian and English were spo- ken. Chicken broth, cabbage rolls, cholent, vegetable stew, chicken schnitzel, latkes, Black Forest cake, almond torte, apple compote, lemon tea and coffee were served.4 Avram and Masha's son John Zeleznikov remembered:

Customers would come in at the start of the day and stay for hours on end. Many were emulating their life before the war in Vienna. For some it was the food and social connection. For others it was just a social outlet. Many of them were Holocaust survivors. Usually men who remained single for the rest of the lives. Many couldn't look after themselves. Some of them were very lonely. And so my mother developed a three-course meal that wasn't on the menu but was especially for those customers.

Pictures by or of Maria Cosway, Jefferson crush

Speaking of Jefferson …

Wishing you “a shabby, unhappy, futile existence”

And other correspondence from Lord “no more Mr Nice Guy” Randolph

Lady Randolph to Winston, 7 August 1893 (CHAR 1/8/45-46)

Hotel Victoria

Kissingen

Monday 7th August [1893]Dearest Winston,

We have just received y[ou]r letters, & are very pleased to think you are enjoying yourselves– I am glad of course that you have got into Sandhurst but Papa is not very pleased at y[ou]r getting in by the skin of y[ou]r teeth & missing the Infantry by 18 marks. He is not as pleased over y[ou]r exploits as you seem to be!

…

Best love – & look after y[ou]rself & Jack.

Your loving Mother

JSC

Lord Randolph to Winston, 9 August 1893 (CHAR 1/2/66-68)

9 Aug. 1893

My dear Winston,

I am rather surprised at your tone of exultation over your inclusion in the Sandhurst list. There are two ways of winning in an examination, one creditable the other the reverse. You have unfortunately chosen the latter method, and appear to be much pleased with your success.

The first extremely discreditable feature of your performance was missing the infantry, for in that failure is demonstrated beyond refutation your slovenly happy-go-lucky harum scarum style of work for which you have always been distinguished at your different schools. Never have I received a really good report of your conduct in your work from any master or tutor you had from time to time to do with. Always behind-hand, never advancing in your class, incessant complaints of total want of application.

…

With all the advantages you had, with all the abilities which you foolishly think yourself to possess & which some of your relations claim for you, with all the efforts that have been made to make your life easy & agreeable & your work neither oppressive or distasteful, this is the grand result that you come up among the 2nd rate & 3rd rate class who are only good for commissions in a cavalry regiment.

…

Do not think I am going to take the trouble of writing to you long letters after every folly & failure you commit & undergo. I shall not write again on these matters & you need not trouble to write any answer to this part of my letter, because I no longer attach the slightest weight to anything you may say about your own acquirements & exploits. Make this position indelibly impressed on your mind, that if your conduct & action at Sandhurst is similar to what it has been in the other establishments in which it has sought vainly to impart to you some education, then that my responsibility for you is over.

I shall leave you to depend on yourself giving you merely such assistance as may be necessary to permit of a respectable life. Because I am certain that if you cannot prevent yourself from leading the idle useless unprofitable life you have had during your schooldays & later months, you will become a mere social wastrel one of the hundreds of the public school failures, and you will degenerate into a shabby unhappy & futile existence.

…

Your affectionate father,

Randolph S.C.

From Winston to Lady Randolph, 17 September 1893

Sept. 17 [1893]

My dear Mamma,

Your letter arrived last night, and made me feel rather unhappy. I am awfully sorry that Papa does not approve of my letters. I take a great deal of pains over them & often re-write entire pages. If I write a descriptive account of my life here, I receive a hint from you that my style is too sententious & stilted. If on the other hand I write a plain & excessively simple letter – it is put down as slovenly. I never can do anything right.

…

As to the leave – it is very hard that Papa cannot grant me the same liberty that other boys in my position are granted. It is only a case of trusting me. As my Company Officer said he “likes to know the boys whom their parents could trust” & therefore recommended me to get permission sorted for. However it is no use my trying to explain to Papa, & I suppose I shall go on being treated as “that boy” till I am 50 years old.

…

It is a great pleasure to me to write to you unreservedly instead of having to pick & choose my words & information. So far I have been extremely good. Neither late nor lazy, & have had always 5 minutes to wait before each parade or study.

Yesterday I went out riding with a charming Eton boy (he is 19½) whose acquaintance I have made. We got to Aldershot & were having a stiff gallop when his saddle slipped round & he fell on his head. Of course he was stunned & for now got concussions of the brain. I revived him as well as I could – with brandy & water then had to hire a cab to drive all the way back to Sandhurst. I took him to see a doctor on the road who said he had had a marvellous escape of breaking his neck. The whole thing was a great responsibility & [rather an] experience.

…

Well I have told you all about my life. I am cursed with so feeble a body, that I can hardly support the fatigues of the day; but I suppose I shall get stronger during my stay here.

…

Good-bye dear darling Mamma. Ever so much love & more kisses,

From your ever loving son,

Winston S. Churchill.

From Lord Randolph to Winston, 21 April 1894

21 Apr 1894

Dear Winston,

I have received you letter of yesterdays [sic] date & am glad to learn that you are getting on well in your work. But I heard something about you yesterday which annoyed & vexed me very much. I was at Mr Dent’s about my watch, and he told me of the shameful way in which you had misused the very valuable watch which I gave you. He told me that you had sent it to him some time ago, having with the utmost carelessness dropped it on a stone pavement & broken it badly. The repairs of it cost £3.17s. which you will have to pay Mr Dent. He then told me he had again received the watch the other day and that you told him it had been dropped in the water. He told me that the whole of the watch was horribly rusty & that every bit of the watch had had to be taken to pieces. I would not believe you could be such a young stupid. It is clear you are not to be trusted with a valuable watch & when I get it from Mr Dent I shall not give it you back. You had better buy one of those cheap watches for £2 as those are the only ones which if you smash are not v[er]y costly to replace. Jack has had the watch I gave him longer than you have had yours; the only expense I have paid on his watch was 10/s for cleaning before he went back to Harrow. But in all qualities of steadiness taking care of his things & never doing stupid things Jack is vastly your superior.

Your v[er]y much worried parent,

Randolph S. Churchill

As some readers may know, Lord Randolph died not a few months later, probably of syphilis, at the age of 45. Winston wrote his biography and having failed to win his fathers’s approval during his lifetime, spent the rest of his own life trying to be worthy of it. Read a review of the book of letters this came from here.

Build utopia for mathematicians, make hundreds of billions

I don’t listen to a lot of podcasts about business success, but this one seems to be one of the best. And this story is pretty amazing, though I didn’t listen to all 3 hours of it.

HT: Jim Savage.

Abstract philosophers: who needs them?

Darren Allen. Until this week, I’d never heard of this guy. But he’s been churning out books and accomplished articles like the one extracted below. He writes about philosophy, seems to know his subject, and yet it’s great fun to read — it’s jaunty and clear. It might be a little too jaunty, a little too quick to dismiss. I guess it all depends on what he’s got to offer in the stead of what he’s critiquing. I shall poke around some more and see what I find out.

Abstract philosophy is the exclusive use of the thinking mind to find truth. This doesn’t just mean working out problems in the head, but also perceiving abstractly; seeing and hearing the world divided up into concepts, filtered through the ‘screen’ of the thinking mind, and assuming that this divided representation is the world. This activity is so common that you’d be forgiven for thinking that the world it presents is reality, just as you’d be forgiven for thinking that all reasoning about it is philosophy.

Abstract thinking about abstract experience is the only thing that happens in universities and just about the only thing you’ll find in the philosophy section of a bookshop or library. When people use the word ‘deep’, they’re usually thinking of the kind of difficult ideas that abstract philosophers talk about. … Philosophy is essentially the haute-couture of literature, the production of ugly and unusable clothing for those who live in a world artificially rearranged so that they can be worn.

An entirely institutionalised existence that is designed to insulate professional thinkers from reality makes books full of unreal concepts appear as useful and beautiful to philosophistas as an upside down dress does to fashionistas.

[P]rofessional philosophers rely exclusively on the thinking mind to understand truth, which is like relying exclusively on cookbooks to understand food, or textbooks to understand the human body. It’s fair to say that most philosophers, psychologists and cognitive scientists believed and still believe—either explicitly or implicitly—that abstract reason and reality are more or less the same thing, that consciousness is thinking or self reflection, that only thought can grasp the essence of reality, that the essence of things is literally a form of thought, or that there is no point of view outside of reason from which reason can be judged. …

This is why so many philosophers are baffled by reality. They take experiences which cannot be completely reduced to thought, think about them, and then find their thoughts perplexing. One of the earliest philosophers, for example, Zeno of Elea, who lived around 2,500 years ago, was a very confused man. He reasoned that no object—an arrow, for example—can ever get anywhere, because there are an infinite number of halfway stages it must first reach en route. A century later, Socrates and his disciple Plato became famous for the vast number of things they were confused about; such as what ‘virtue’ is, what ‘knowledge’ is and what ‘thing’ thought is ‘of’. Eight hundred years later, Augustine of Hippo couldn’t work out where the past and future are, or how time can ever be measured. A thousand years later, it was René Descartes’ turn to be baffled by the contents of his own mind. He split experience into mind and matter and was then mystified by how thought could interact with a non-thinking body; a problem which has menaced professional minds ever since. A hundred years later, Hume couldn’t understand what consciousness was, or morality, or causality, because none of them seem to exist in the objective world.

And so it goes on. There are thousands of cases of the same sort; straightforward affairs made puzzling by thought. Just as management exists in order to solve problems created by management, and teachers exist in order to educate people made stupid by the existence of schools, and technology exists in order to solve problems created by technology, so the source and root of these fanatically rational activities, abstract thinking, sets about trying to philosophically solve problems that it has created by thinking. Zeno’s arrow, like Augustine’s time, is not a series of discrete mind-isolated moments or steps, and Plato’s ‘good’, like Hume’s ‘morality’, is not an abstract idea. They are all brought into existence, like Descartes’ perplexing subjects and objects, by the thinking self. The hyper-focusing mind creates mental objects of will, motion, meaning, the good and so on—it creates knowledge—and then is mystified at how they can be objects; how, for example, as Ludwig Wittgenstein asked, I can ‘know your pain’—as if it were a nasty drink that I could dip a straw into; or how I can ever remember anything—as if memories were books on shelves that a little man in my mind has to index and retrieve; or how I can ever understand anything anyone says—as if I have to consult a dictionary to ‘look up’ all the words they utter.

The reason that so few philosophers ever criticise this activity, the conversion of experience into ‘knowledge’, into a kind of substance which can be produced and consumed, is that they are its producers and we are its consumers. Knowledge as a thing which can be owned, managed, packaged and consumed, automatically turns it into a scarce resource, which, like any other scarce resource, acquires a value which stigmatises the many, the very many, who cannot get their hands on it. Any thinker who rejects this state of affairs—the iniquitous foundation of the gnosocratic knowledge and ‘education’ industry—is ridiculed, rejected or ignored, or, at best, misunderstood by the academic world.

A culture in the ascendant

Heaviosity half hour with French Philosophers

I’m a sucker for profound-sounding stuff. And some profound-sounding stuff is profound. It might take work but it’s worth it. Problem is, how do you know? This is not one of those posts that bemoans postmodernism as if I understand a lot of it and it’s trivially absurd. If it’s trivially absurd, ignore it. A lot of French philosophy is pretty intriguing. But I rarely get far as it drifts into incomprehensibility — at least for me. Do I understand Derrida? Nope. Is he a nit wit? No idea. But one has to be able to move on if you’re not getting much out of it.

Anyway, here’s a generalisation. French philosophers often have some core insight that is hugely consequential. Take Foucault for instance — his ideas about power being entangled in discourse and surveillance, the role we all play in making ourselves subjects of power. But there’s lots of French stuff that’s super hard to understand and, when you make the effort isn’t that rewarding. And wild, truthy claims. That there are ‘ruptures’ in the fabric of culture. An OK way to talk I guess, but also an easy way to become untethered from reality.

Rene Girard

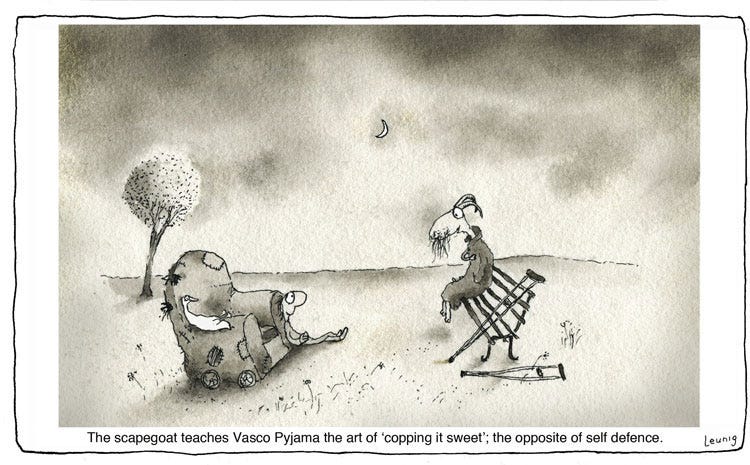

Which brings me to Rene Girard. His basic idea that mimetic desire is super important is obviously profoundly important and all the more so in the age of social media. But then it gets grafted onto a far more speculative idea — that of the scapegoat. So I was glad to read Scott Alexander saying the same thing.

Philosopher / theologian Rene Girard’s famous book I See Satan Fall Like Lightning [is] an ambitious theory-of-everything for anthropology, mythography, and the Judeo-Christian religion. … Girard’s starting point is the similarity between Bible stories and pagan myths. You’ve heard about this before - dying-and-resurrecting gods, that sort of thing. You might expect Girard, a good Catholic, to reject these similarities. He doesn’t. He says they’re real and important. Pagan myths resemble the Bible because they’re both describing the same psychosocial process. The myths are distorted propaganda supporting the process, and the Bible is a clear-eyed description of the process which reveals it to be evil. …

Girard calls this process “the single-victim process” or “Satan”. It goes like this:

Most (all?) human desire is mimetic, ie based on copying other people’s desires. The Bible warns against coveting your neighbor’s stuff, because it knows people’s natural tendencies run that direction. It’s not that your neighbor has particularly good stuff. It’s that you want it because it’s your neighbor’s. Think of two children playing in a room full of toys. One child picks up Toy #368 and starts playing with it. Then the other child tries to take it, ignoring all the hundreds of other toys available. It’s valuable because someone else wants it.

As with the two children, conflict is inevitable. As the mimetic process intensifies, everyone goes from complicated individuals with individual wants, to copies of their neighbors (ie their desires copy their neighbors’ desires, and they become the sort of people who would have those desires). Alliances form and dissipate. There is a war of all against all. The social fabric starts to collapse.

Instead of letting the social fabric collapse, everyone suddenly turns their ire on one person, the victim. Maybe this person is a foreigner, or a contrarian, or just ugly. The transition from individuals to a mob reaches a crescendo. The mob, with one will, murders the victim (or maybe just exiles them).

Then everything is kind of okay! The murder relieves the built-up tension. People feel like they can have their own desires again, and stop coveting their neighbors’ stuff quite so hard, at least for a while. Society does not collapse. If there was no civilization before, maybe people take advantage of this period of relative peace to found civilization.

(Optional step 5) Seems pretty impressive that killing one victim could cause all this peace and civilization! The former mob declares their victim to be a god. Killing the god was the necessary prerequisite to civilization. Now the god probably reigns in heaven or something. Maybe they die and resurrect every year. Whatever.

Rinse and repeat.

Girard is against this process. Not just because it involves violent mobs lynching innocent people (although it does), but because that step perpetuates the whole cycle: people greedily desiring whatever their neighbors have, people hating their neighbors, internecine war of all against all. …

So, concludes Girard, the single-victim process is the basis of all ancient civilization. The pagan myths were written by people who had recently been in the mobs. It accurately reflects their understanding of events: there was some kind of looming crisis, we figured out that an ugly foreigner was responsible, we killed him, and that solved the problem (and optionally, he might be a god). …

So how does the Hebrew Bible escape this failure mode? Girard says divine intervention. God (here meaning literal God, exactly as the average churchgoer understands Him) tried to break the reign of Satan (here meaning metaphorical Satan, the single-victim process) over the Jewish people, by constantly providing them with examples of the single-victim process being bad and ensuring those examples were written up accurately. He got the Israelites to obsess over these examples and worship them as a holy text, trying to hammer the whole thing into their heads. Finally, He sent His only begotten Son as the perfect victim, who would undergo the process in its entirety and have it be written up with unprecedented attention to detail. This extra-compelling example finally penetrated the Israelites’ thick skulls. Although Peter and the other disciples sort of joined the mob in denying Jesus at the beginning, after the Resurrection they started thinking previously barely-thinkable thoughts, like “what if our mob was in the wrong?” and “what if mob violence is bad?”

Wherever Christianity spread, people had the mental toolbox to try to consider the victim’s perspective. They didn’t always use the toolbox very effectively, and occasional outbreaks of the single-victim process continued - lynchings, literal witch hunts, metaphorical witch hunts. But you got increasingly long periods where it didn’t happen at all, and in any case it no longer seems like the central feature of civilization. Satan has been cast down.

Okay, But This Is All Crazy, Right?

Yeah, I think mostly crazy.

I originally picked up this book because I wanted to learn more about mimetic desire. I think there might be something to this part. … But Girard lost me with the part about the myths. Most pagan myths have nothing to do with the single-victim process (eg labors of Hercules, Jason and the Golden Fleece, rape of Persephone, the Iliad, the Trojan Horse, the Odyssey, etc, etc, etc). The same with most Bible stories (Adam and Eve, Noah’s Flood, the Tower of Babel, the Ten Plagues, the Ten Commandments, etc). It kind of seems like the sort of thing where Freud can claim all myths are about castration. There are lots of myths, and they’re about lots of things.

My sentiments entirely.

Jean-Pierre Dupuy

I recently discovered Jean Pierre Dupuy, a French philosopher who poked around in issues as deep as any of them (or so it seems to my tiny mind), but who is nevertheless a model of clarity in expression. Here is his introduction to the English Translation of his The mark of the sacred.

Looks super-interesting but I’ve not read much further at this stage.

This book treats a series of questions that concern all of mankind. To what do we owe our faculty of reason—that power of thought in which we take so much pride, and which philosophers since Aristotle have considered to be uniquely human? Is rationality equally distributed among all peoples? Was it inborn in us from the beginnings of our existence on earth, or did it first blossom only with the invention of two things for which the Western world is pleased to take credit: democracy and philosophy? Did it, in either case, subsequently achieve its fullest flowering as a consequence of modern advances in science and technology? If it did, must we say that instrumental rationality—the ability to relate ends to means that is peculiar to Homo œconomicus—represents the unsurpassable culmination of human reason? Or is it merely a degraded and inadequate facsimile?

Whether reason is innate or acquired, we know that it can be lost, individually and collectively. But what does this tell us about the nature of reason? Not only the murderous rages, the genocides and the holocausts, but also the folly that leads humanity to destroy the conditions necessary to its survival—what do these things teach us about the absence of reason? In 1797, Francisco Goya made an etching to which he gave the title El sueño de la razón produce monstruos. It shows a man fallen asleep in his chair, his head resting heavily on a table, surrounded by terrifying creatures of the night, owls and bats. A large cat looks on. With this arresting image an artist who had upheld the ideals of the French Revolution in opposition to many of his countrymen expressed his horror at the awful massacres of the Terror. The title is generally translated as “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.” But the Spanish word sueño, as it happens, may mean either sleep or dream. In this second sense Goya’s title acquires a much more disturbing meaning. It is not the eclipse of reason that produces monsters; on the contrary, it is the power of reason to dream, to fantasize, to have nightmares—to unleash the demons of the imagination.

To all these questions there is a simple reply, or at least a reply that is simply stated: reason, like all human institutions, has its source in religion. It is the same answer one finds in the French tradition of social science inaugurated by Émile Durkheim and Marcel Mauss. Durkheim, in his great work The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, congratulated himself on having established that “the fundamental categories of thought, and therefore of science, have religious origins.” As a result, he concluded, “it can be said that nearly all great social institutions are derived from religion.” If Durkheim was right, as I believe he was, the adventures and misadventures of human reason will make no sense to us unless we examine them in the light of his discovery.

Even though the topics I discuss in this book are of universal importance, the conclusions I draw cannot help but arouse sharply differing reactions among my readers, depending in large part on the place of religion in public life that they are accustomed to regard as proper. In the Western world, probably no two countries are separated by a greater distance with regard to the place reserved for religion than the United States and France, as Alexis de Tocqueville was perhaps the first to point out when he traveled through America in the 1830s. The gap between them is hardly smaller today than it was in Tocqueville’s time. It may be well, then, to say a few words at the outset in the hope of preventing at least the grossest misunderstandings.

France is proud to describe itself as a secular country. It is telling that the meaning of the phrase pays laïc cannot easily be conveyed in English. Secularism in the French sense does not signify the neutrality of the state, as it does in America. The doctrine of the neutrality of the state, due to classical liberalism, assumes that the state is incompetent to decide what constitutes the good life, and therefore cannot take sides between competing conceptions. In France, by contrast, secularism is understood to be a fundamentally anti-liberal and “perfectionist” concept. On this view, the state has both the authority to say in what the good life consists and the right to command obedience to its will in the public sphere. It is here that the problem of religion makes itself felt most acutely. The republican tradition in France makes conformity to reason the sole qualification for taking part in public life. Condorcet expressed the idea beautifully: “Generous friends of equality, of liberty, unite to demand from your governors an education that will make reason the property of the people.” Thus the ideal of the French Revolution—rationality as the highest public virtue.

Now, to the French secular mind, religious faith of every kind seems profoundly irrational. Religion and its visible signs therefore have no legitimate place in the public sphere in France, where education is obligatory and free of charge for all. The thought of a president of the republic taking the oath of office on a Bible is unimaginable. Were the president to conclude his inaugural address with the words “God save France,” there would be rioting in the streets. When the nation’s currency was the French franc, the idea that banknotes might bear the legend “In God We Trust” would have been simply inconceivable. These commonplaces of American political culture are deeply shocking to my fellow citoyens, no less shocking than the recent French law prohibiting the display of emblems of religious affiliation in schools, whether the Islamic veil, the Jewish skullcap, or Christian crucifixes greater than a certain size, seems to many of my American friends. For someone like myself, who loves both countries, this mutual incomprehension is disheartening.

Tocqueville was forcibly struck above all by the religious faith of the American people. Having come to America to study democracy, he came afterward to think that the former was the necessary condition of the latter. As he so memorably put it, “I doubt whether any man can endure, at one and the same time, complete religious independence and complete political freedom; and I am led to believe that, if a man is without faith, he must serve another, and, if he is free, he must believe.” Some of the most eminent political philosophers in France today have strongly criticized Tocqueville on this point. The true spirit of democracy, they say, was there to be found in his own country, post-revolutionary France.

A democratic society is not one that is in harmony with its basic principles, as American theorists such as John Rawls have maintained. Just the opposite is true: it is one in which these principles are perpetually called into question, a social and political regime marked by conflict and division over the very values on which it is founded; indeed, it is of the essence of democracy that such questioning should be constant and open-ended. In Tocqueville’s time, France was torn between those who favored democracy and those who opposed it. This very tension, it is said, worked to strengthen democracy. French political thought today, or at least its most secular element, therefore concludes it is futile to suppose, as Tocqueville did, that religion can erect a durable barrier against the subversive influences that erode the foundations it has given itself. God and religion will inevitably perish as a result of the growth of democracy.

In America, the growth of religious fundamentalism in recent decades, and the excesses to which it has given rise, have produced by way of reaction an assault against religion in which God has become, or become once more, the perfect scapegoat—and all the more perfect as he is believed not to exist.

The titles of bestsellers that line the shelves of American bookstores—The God Delusion, God Is Not Great, The End of Faith, Breaking the Spell—do not deal in nuance. Together, they amount to a declaration of war against the religious foundations of American democracy.

It is tempting to imagine that the secular crusade of the French Left and the anti-religious crusade of the American Left are somehow similar. And yet they have nothing in common. Few books by religion-bashers in England and America are translated into French. The ones that are sell poorly, and their ideas have no resonance whatever in the quarrels over secularism that regularly enliven French political debate. There are two reasons for this. The first is that scholars and intellectuals in France have a hard time taking seriously what they consider to be the work of mere pamphleteers, whose outstanding characteristics are, on the one hand, a lack of culture, and, on the other, a weakness for arguments that rely on biological theories of evolution and research in the cognitive sciences. But this is nothing new. Attempts to reduce social phenomena and the symbolic dimension of human existence to purely natural causes have never gotten a warm welcome in France.

The second reason has to do with the history and sociology of religion, which, it must be admitted, is not the strong point of the new atheists in England and America. One often has the impression that they take particular delight in making Christianity out to be no less irrational than any other religion, and therefore one more reason for dismissing religion in all its forms. French thinkers from Durkheim onward, by contrast, deepening an insight famously associated with Max Weber, have argued that secularization—what Weber called the disenchantment of the world—was a paradoxical consequence of the spread of Christian faith that, in its turn, prepared the way for the flourishing of economic rationality. Indeed, it is not uncommon today to hear Christianity described as “the religion of the end of religion.” The blindness of the new atheists to the fundamentally distinctive nature of Christianity is taken in France to disqualify them from taking part in the debate about the nature of religion and its future.

I mention all these things here in order to remind my American readers that one can hardly write a book on the religious origins of human reason without taking into account the settled prejudices of one’s audience. Nevertheless, in the pages that follow, I touch only in passing on questions that are primarily of interest to historians and sociologists of religion. I concentrate on a different set of questions, philosophical questions, which are logically prior to the ones that concern historians and sociologists. I begin by considering a notion that lay at the heart of religious anthropology when it was still recognized as a discipline in its own right, namely, the sacred. I do not dispute the vagueness of this concept, nor do I try to give an exhaustive account of what it involves. Instead I characterize its formal properties, and go on to show that human reason preserves the mark of its origins in the sacred, however much it may regret this fact. I then take up in turn several related kinds of rationality in which the mark of the sacred may yet be plainly seen, in science, politics, economics, and strategic thought.

Along the way I develop three lines of argument: first, that the Judeo-Christian tradition cannot be identified with the sacred, since it is responsible for the ongoing desacralization (or disenchantment) of the world that epitomizes modernity; second, that desacralization threatens to leave us defenseless against our own violence by unchaining technology, so that unlimitedness begins little by little to replace limitedness; third, the greatest paradox of all, that in order to preserve the power of self-limitation, without which no human society can sustain itself and survive, we are obliged to rely on our own freedom. It will be clear, I think, from what I have already said about the differences between France and America, that in making these claims I come directly into conflict with both French secularists and American religion-bashers, since they all consider religion to be the height of irrationality, whereas they themselves adamantly believe in Reason, pure and immaculate; with religion-bashers, in particular, since they fail to see what even secularists accept, namely, that Christianity has been the driving force in bringing about the secularization of society; with secularists, in particular, since they fail to see that reason in its various forms continues still today to display the mark of the sacred; and, of course, with religious fundamentalists of all faiths, since they resemble their rationalist adversaries in regarding reason and the sacred as strangers to each other, locked together in a merciless struggle to the death. That’s a lot of people to take on at once.

One last thing. The task of bringing over not only my words, but the intricate structure of my arguments and their subtlest shades of meaning, from the language and culture of France to the language and culture of America has required a translator of exceptional talent. Once again I am pleased to be able to give my warmest thanks to Malcolm DeBevoise.

Nicholas: Another fascinating guidance around the world - of the world of personalities and thought. Favourites from to-day: Exchanges between Churchill pére et fils et mére et fils; Darren Allen on "...affairs made puzzling by thought" (laugh out loud - almost); Café Sheherezzade and Arnold Zable's book - which I read some years ago with memories of visits to Eastern Europe-in-St Kilda from many decades ago; that Virtue AND signalling are good -something I've long thought when reading/hearing the sneers from Peta C and A Bolt and gang; the story of Nobel winner Chandrasekan and his class of two - both of whom won Nobel Prizes in Physics; and the discussion of Socrates and the distinguishing "principles" of Dialectal (the argument (rigorous) to uncover the truth - and the Eristical (a new term for me) out of which via sophistry and rhetoric there is a "winner" of the argument - though whether truth is found or not is not necessarily the point. This latter revelation indicted so-called "debate" in our British-derived Parliamentary system and as well the way in which our British-inherited legal system operates - totally adversarial - the truth not sought - merely a winning in the clash of prosecutor and defence. Thanks, NG. Heaviosity - now has its own corner in your Saturday blog! Bravo!