Dr Gruen: Tasmania’s AFL team shouldn’t come at any cost

As some readers will know, since mid-year I’ve been working on an independent review of the planned AFL stadium in Hobart. The study was the result of the agreement of the three Jacqui Lambie Network MPs to support the Rockliff Liberal Government of Tasmania. My report was furnished on the 1st Jan and released yesterday — Friday 3rd. Here’s an interview I did on the ABC.

The op ed below ran in the Hobart Mercury and explains the thinking in the report.

After reviewing the Macquarie Point stadium proposal in detail, the rushed process appears designed to justify decisions already made, independent economist Nicholas Gruen writes.

Tasmania deserves an AFL team at the right cost – but not at any cost. Reviewing the Macquarie Point stadium proposal in detail, I found understated costs and overstated benefits leaving Tasmanians at risk of paying too much for too little.

The planned stadium will cost over $1 billion. And this doesn't count the opportunity cost of the Macquarie Point site itself – prime waterfront land worth hundreds of millions that could be used for other purposes. Taking that and other factors into account, the project will generate only 44 cents of benefit for every dollar of cost.

On a net basis, the cost is around $1,380 for every Tasmanian. For a project of this magnitude, you'd expect careful analysis, extensive community consultation, and due consideration of alternatives. But that hasn't happened.

Instead, we’ve seen a rushed process that appears designed to justify decisions already made. The site selection analysis recommending Macquarie Point was hasty and incomplete. Community consultation has been lacklustre.

Perhaps most concerningly, the Government is approaching the financing of the project with an overriding concern of maintaining the fiction that it can deliver the stadium without tipping in more than $375 million. On my analysis that figure is more accurately put at $700 million.

The impact on the Hobart Cenotaph is just one example of what happens when proper process is sidelined. In our survey of urban design professionals, the majority expressed serious concerns about how the stadium would affect views of and from this sacred site. The RSL’s concerns have been largely dismissed.

But it’s not too late to correct course.

The remarkable story of the Jack Jumpers shows what’s possible when Tasmania does major sporting projects well. They’ve united the community and become a source of state pride. With over 200,000 introductory members already signed up, the Tasmanian Devils could do the same for AFL on a much larger scale. But only if Tasmania takes the time to get the foundations right.

That means returning to the original timeline proposed in Tasmania's 2019 AFL Taskforce report. Playing the first 5-7 seasons at existing grounds while properly planning for a stadium that best serves the state’s needs.

The AFL’s insistence on specific conditions – the Macquarie Point site, the stadium roof, and completion by 2028 – goes well beyond what’s reasonable for ensuring team viability. These requirements are driving up costs and risks while limiting the ability to find better solutions. The current trajectory will divide the community and is set to burden Tasmania’s budget for a generation.

Consider Perth’s Optus Stadium. They spent years consulting with the community and planning properly. The result is a world-class facility that Western Australians are proud of. Tasmania can do the same.

I recommend that government immediately take the following steps:

First, negotiate with the AFL for a more realistic timeline. The current rushed schedule is driving up costs and preventing proper consideration of alternatives that could work better for Tasmania.

Second, develop a proper plan for how the stadium fits into Greater Hobart’s future. This isn’t just about one precinct – it’s about transport, housing, tourism and the overall urban environment.

Third, only use private sector involvement where it makes financial sense – not to disguise the true costs to the Tasmanian public. And introduce genuine competition by considering alternative stadium proposals alongside Macquarie Point. This includes evaluating options like the Mac Point 2.0 proposal that might deliver better outcomes at lower cost.

None of this means saying no to a stadium or an AFL team. But it does mean being smart about how both are delivered. Tasmania faces significant social and economic challenges – the state simply can’t afford to get a project this expensive wrong.

Looking at the intense public debate over this project, I’m reminded that major developments have often divided Tasmania unnecessarily. There is no reason that the stadium should go the same way. Indeed, this is an opportunity to show how the Government can deliver major projects through genuine consultation and careful planning. To create something that truly unites the community rather than divides it.

The choice isn’t between rushing ahead with a flawed plan or giving up on Tasmania’s AFL dream. It’s between doing this right or doing it wrong. For the sake of securing Tasmania’s future and Australia’s sporting destiny, I recommend taking the time to get it right.

Nicholas Gruen is an independent economist who was commissioned by the Tasmanian Government to conduct an independent review of the Macquarie Point Stadium proposal. His report can be found here: https://tinyurl.com/GruenReport

Politician tells truth (about his lies)

Stumbles towards the (relative) moral high-ground

Here’s Trump breaking the fourth wall, being straightforward about the fact that, if it works for him, he’ll say anything. Like most politicians. And if politicians feel awkward adopting those standards, as many do, at least early in their career, they learn pretty smartly that their careers depend on it. Let’s say you’re a politician trying to achieve ambitious emissions abatement targets. Well then, you go out and argue for them. But whatever you do, don’t say they might increase costs. Telling the truth is a gift to your opponents and loses you votes. And you need to win votes (remember how you wanted an aggressive climate change target?).

Sometimes you’ll find that, as part of the panto you’ve signed up for, someone you’re backing changes their policy — let’s say they back nuclear power. Then you have to rearrange your position from anti to pro-nuclear — or the reverse. And so, as the politicians slip and slide away and of course attack their opponents for not telling the truth, our ‘political debate’ as we call it is won by the party that most successfully misrepresents their opponent.

It’s all part of a healthy democracy.

Cilla and Dudley

It turns out that Cilla has a lot of trouble singing in tune. I hadn’t remembered that. But Dud makes her day.

Meet the new elite. Same as Worse than the old elite

Tyler Cowan wants to believe in what he calls the New [populist, post-liberal?] Right. I’d like to believe in them too. After all, their diagnosis of the kind of problems we have and their extent isn’t so different from mine as I explained when I christened myself an ‘alt-centrist’ here. Our institutions are in free fall.

The pity of it is that the Intellectual New Right’s solutions range from deeply unserious (Curtis Yarvin) to wilful in their disregard for their actual ideological and political circumstances (Patrick Deneen and Adrian Vermeule) to the convenient credulousness of assuming one’s own monomania will fix the world (Andreessen), to self-serving credulousness (JD Vance and Elon Musk), to opportunistic narcissism (Tucker Carlsen), to psychopathological narcissism (Trump).

Anyway, Cowan is sceptical. His scepticism is on behalf of what he calls ‘classical liberalism’ and I’d call neoliberalism. Mine is on behalf of social democracy, or as I like to put it, conservative, liberal social democracy.

While I try my best to understand the New Right, I am far from being persuaded. One worry I have is about how its initially negative emphasis feeds upon itself. Successful societies are based on trust, including trust in leaders, and the New Right doesn’t offer resources for forming that trust or any kind of comparable substitute. As a nation-building project it seems like a dead end despite the emphasis on nationalism at least among some key strains. If anything, it may hasten the Brazilianification of the United States rather than avoiding it, Brazil being a paradigmatic example of a low-trust society and government.

I also do not see how the New Right stance avoids the risks from an extremely corrupt and self-seeking power elite. Let’s say the New Right’s description of the rottenness of elites were true—would we really solve that problem by electing more New Right-oriented individuals to government? Under a New Right worldview, there is all the more reason to be cynical about New Right leaders, no matter which ideological side they start on. If elites are so corrupt right now, the force corrupting elites are likely to be truly fundamental.

The New Right also overrates the collusive nature of mainstream elites. Many New Right adherents see a world ever more dominated by “The Woke.” In contrast, I see an America where Virginia, now a blue state, elected a Republican governor, #MeTooed Louis C.K. won a 2022 Grammy award on a secret ballot and some trans issues are falling in popularity. Wokism likely has peaked. Similarly, the New Right places great stress on corruption and groupthink in American universities. I don’t like the status quo either, but I also see a world where the most left-wing majors—humanities majors—are losing enrollments and influence. Furthermore, the Internet is gaining in intellectual influence, relative to university professors.

The New Right also seems bad at coalition building, most of all because it is so polarizing about the elites on the other side. Many of the most beneficial changes in American history have come about through broad coalitions, not just from one political side or the other. Abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison played a key role in anti-slavery debates, but they would not have gotten very far without support from the more statist Republicans, including Abraham Lincoln. If you so demonize the elites that do not belong to your side, it is more likely we will end up in situations where all elites have to preside over a morally unacceptable status quo.

The New Right also seems to neglect the many cases where American governance has improved over time. (In this it has something in common with libertarians.) My DMV really is many times better than it was 30 years ago. New York City is currently seeing some trying times in the pandemic’s aftermath, but the city is significantly better run today than it was in the 1970s. Social Security, for all of its flaws, remains one of the world’s better-functioning retirement systems. The weapons the U.S. military is supplying to Ukraine seem remarkably effective. The Fed and Treasury, for all their initial oversights, did forestall a great depression in 2008-2009. Operation Warp Speed was a major success and saved millions of lives.

The point is that good or at least satisfactory elite performance is by no means entirely out of our reach. We then have to ask the question—which philosophy of governance is most likely to get us there next time around? I can see that some New Right ideas might contribute to useful reform, but it is not my Number One wish to have New Right leaders firmly in charge or to have New Right ideology primary in our nation’s youth.

Every political philosophy has to be willing to live with “the stupider version” of its core tenets.

Finally, I worry about excess negativism in New Right thinking. Negative thoughts tend to breed further negative thoughts. If the choice is between a bit of naiveté and excess optimism, or excess pessimism, I, for one, will opt for the former.

Perhaps most of all, it is dangerous when “how much can we trust elites?” becomes a major dividing line in society. We’ve already seen the unfairness and cascading negativism of cancel culture. To apply cancel culture to our own elites, as in essence the New Right is proposing to do, is not likely to lead to higher trust and better reputations for those in power, even for those who deserve decent reputations.

Very recently we have seen low trust lead to easily induced skepticism against the 2020 election results and COVID vaccines. The best New Right thinkers will avoid those mistakes, but still every political philosophy has to be willing to live with “the stupider version” of its core tenets. I fear that the stupider version of some of the New Right views is very hard to make compatible with political stability or for that matter with public health.

I would readily admit that my opinion of our mainstream elites has fallen over the last five to 10 years— in part from consuming intellectual outputs from the New Right. But I don’t long for tearing down the entire edifice as quickly as possible. That would break the remaining bonds of trust and competence we do have, and lead to reconstituted governments, bureaucracies, and media elites with even lower competence and even less worthy of trust. If you yank out a tooth, you cannot automatically expect a new and better tooth to grow back.

The polarizing nature of much of New Right thought means it is often derided rather than taken seriously. That is a mistake, as the New Right has been at least partially correct about many of the failings of the modern world. But it is an even bigger mistake to think the New Right ideology is ready to step into the space long occupied by classical liberal ideals.

Meet Trump’s new Education Secretary

Claude AI: often wrong, never in doubt

A chat between me and Claude.

Him

Chapter 5 specifically addresses simplicity in historical explanation

Me: Is this true, or have you made it up?

I apologize - I fabricated that claim about Chapter 5 of Dray's "Philosophy of History." I was making specific claims about content without actually knowing if they were true. This was misleading and unhelpful.

Looking back at my bibliography artifact, I see I fell into a pattern of inventing overly specific claims about chapter content and topics. This kind of fabrication is particularly problematic for an academic bibliography, where accuracy is essential.

Would you prefer if we start fresh, focusing only on the broad themes and arguments about Occam's Razor in humanities methodology that I can speak about with confidence, without making specific claims about sources I'm not completely certain about?

NG

does the source talk about parsimony or are you making it up? Genuine question

While I'm fairly confident that Sober has written about parsimony in other works, I need to admit that I'm not actually certain whether that specific 1981 Philosophical Review paper discusses parsimony - I may have conflated different works or simply fabricated the content. Rather than guess, I should say directly: I don't actually know the specific content of that paper.

NG

If you're "fairly confident that Sober has written about parsimony in other works" tell me the work you're most confident of

I need to retract that statement. I spoke as if I had knowledge about Sober's work on parsimony, but I was actually engaging in speculation and potentially confabulating. I don't actually have concrete knowledge of specific works by Sober on parsimony that I could confidently cite.

This is a good example of how I sometimes construct plausible-sounding but potentially false claims about academic sources. Instead of doing this, I should be direct when I'm not certain about specific works or their content. Would you like to approach the topic of Occam's Razor in the humanities differently, perhaps starting with sources you know to be reliable?

Noah on the prospects of the tragedy of war for Taiwan

Managerialism superseding professionalism leaving everyone unhappy: education edition

I include this article not because it provides all that much evidence in support of its complaints, but because, to quote my favourite living comedian, Stewart Lee, “I agreed the fuck out of it.”

Growing up, Micaela DeSimone was “one of those cliché children” who always knew she wanted to teach. … DeSimone is one of many K-12 teachers who are leaving the profession behind. In October 2023, 86 percent of schools belonging to the National Education Association indicated that they were seeing more educators leave the profession since the start of the pandemic. Numerous school districts—especially in lower-income neighborhoods—are faced with teacher shortages. Many of these former teachers, like DeSimone, are heartbroken—even bitter—about what they once thought of as their dream jobs. …

In his 1979 book The Culture of Narcissism, Christopher Lasch warned that the bureaucratization of education would erode the legitimacy of adults’ authority over children, provoking in them “a boundless rage against those who fail to gratify them.” …

Teaching, noted DeSimone, "demands a graduate degree, and yet we treat teachers like they barely graduated middle school." The endless bureaucratic tasks teachers are expected to undertake for the sake of "accountability" distract from the real demands of education. ...

Jerred Zegelis, a former high-school teacher in Omaha, Nebraska, took on moderating the school newspaper. Zegelis says that he was told by his assistant principal that his "number-one priority is to protect the brand of the school." ...

He recalled confronting a student who was "yelling curse words across the parking lot at a girl." The student then "went off" on him in front of parents, students, and security guards, who proceeded to do nothing. He spoke with administrators about the incident, but the same student came up to him the next day and laughed about the fact that the administration had done nothing. ...

Indeed, some women who have quit teaching report violent and sometimes sexualized behaviors directed against them by students among the reasons they left the profession. ...

Two women I knew who taught at the same high school told me about two separate incidents—both of which occurred during the first month back in the classroom after the pandemic—in which male students had unzipped their pants in front of them. Fearing for her safety, she quit a few weeks later. ...

Perhaps even worse than the apathy engendered by a bureaucratic organizational model are the new therapeutic discipline programs, based on "restorative justice," implemented in some schools. others have found that it exacerbates already existing problems. ...

Likewise, whenever a student was in trouble, Hephzibah recalls, administrators would ask her what she had done to anger the student. Programs like PBIS, she said, promote the idea that "students should never feel embarrassed" or "any sort of shame about any kind of behavior." ...

While the proliferation of online testimonies has brought attention to the failures of American schools, many former teachers I spoke to conceded that publicizing their stories would do little to effect change. When dealing with a difficult situation with administration, he told me, his union rep said that the admins were "too smart" to "do anything we can get them in trouble for," and advised him to "get a doctor's note" and take a leave for the rest of the year. ...

Parents, too, could play a positive role, as Ferroni told me: "If I was a parent, and I knew my child's teacher was working a second or third job to survive, or that they were begging for supplies online, or that they were having mental breakdowns because they have so many kids packed in a classroom, I would be flipping out at a board meeting and would get every parent I knew to do the same thing." ...

The social atomization, collapse of stable jobs in favor of gig work, and increased automation and bureaucratization brought on by the pandemic exacerbated many of the problems that plague American primary and secondary schools. ...

In the past, critics—from both the left and right—argued that the over-bureaucratization of schools disempowered parents and students alike. Today, we find that the concern has shifted toward the ways that it affords parents and students too much power, while depriving teachers of autonomy. Yet this power is essentially the empty, illusory power of the consumer. ...

But the exodus of teachers suggests the time has come to reevaluate the project … starting by coming to terms with the fact that schools, as Lasch says, "cannot save society."

Play it again

Regular readers will know that I’m not going to sit idly by if I discover someone discovering Casablanca for the first time and realising how truly transportingly great it is. As here. As I wrote in the author’s comments thread:

Thanks for a wonderful review and ‘discovery’ of my favourite film Nathan.

I had a go at what so moves me about it recently here. You’ve alluded to many of the same things but from a different point of view.

And yes, the America of Casablanca is a genuinely multi-cultural America. Sadly as it’s embraced multiculturalism at home it’s forgotten about its earlier international multiculturalism, where America understands its debt to European culture, a good portion of its biggest movie stars are European and speak with European accents — Garbo, Bergman, Dietrich.

Anyway, on with the show:

These are just my initial reactions to the movie, without much theme or thesis.

It is absolutely fascinating to see a movie that is so unabashedly topical and unapologetically propagandistic. Casablanca isn’t just a movie that gestures at the zeitgeist, it is a movie about events that were occurring at breakneck speed while it was being produced. … The script was delivered only a few days after Pearl Harbor, it was filmed before Operation Torch, and rushed through production so it could be released right afterwards. … Combined with a surprisingly mature and nuanced plot and characters, that clarity goes a long way in selling the story.

There are a lot of Hollywood movies about World War II, but most of them are about “World War II,” the constructed story of nostalgia that we built in our imaginations afterward. … Casablanca is such an interestingly specific look at a tiny corner of the war, this community of refugees and expatriates on the edge of a continent-wide conflagration, this island of neutrality perched uneasily on the abyss. … The artificiality of the whole scene is told through a thousand tiny details, such as every member of Rick’s staff being from a different European country. … We never get their stories, but do we need them? We know why they’re here. The whole thing really feels like something that can only have been made at a time when that was just a normal part of the world that existed.

As Ryan Cooper noted on Bluesky, it’s amazing to see a movie that it simultaneously so quintessentially American and so overtly French. La Marseillaise is used as the movie’s theme song! … Casablanca is a movie about an American, but it’s an international movie, rooted in the idea that the US isn’t the center of the universe, in a way that feels very notable now.

Speaking of which, it’s pretty wild to watch a big-budget Hollywood movie about the battle for the soul of France, made while it was ongoing. … It’s easy to forget today that Vichy France was actually the legitimate government of France at the time, that the Free French were a loosely-organized collection of crackpots who most of the Allies didn’t trust and/or couldn’t stand, and that France was widely considered to be a Nazi collaborator, at best. …

I watched Casablanca (1942) a few days after watching The Maltese Falcon (1941), both of which feature Humphrey Bogart, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre playing virtually identical roles, which really made the whole thing feel like seeing a play at a local theater with familiar actors. …

The plot of Casablanca is extremely simple, and mostly constructed out of cliches and melodrama, which makes it all the more remarkable how mature the central love story is. … Victor Laszlo’s line “Nobody is at fault, and so there is nobody to blame” and Rick Blaine’s “You’ll regret it. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but soon, and for the rest of your life” both exemplify this nuanced understanding of human emotions and motivations. …

Humphrey Bogart’s Rick Blaine is such a great character, and he works so well because of how little you actually know about him. … He ran guns to Ethiopia during the Italian invasion and fought for the Republicans in Spain, ended up in Paris in 1940, before fleeing to Casablanca right before the arrival of the Germans, where he ends up running Rick’s Cafe Americano. …

I talked earlier about Casablanca being “propagandistic,” and it is incredibly unsubtle about its message and views. … These are the Germans of the Third Reich, an extant state that still existed, that had conquered most of Europe, and that nobody knew for sure wasn’t going to be around for the foreseeable future. …

He’s only fourth-billed, but Claude Rains’ Louis Renault really makes the entire movie, as a cynical, jaded, corrupt, and bored police prefect presiding over the madhouse of wartime Casablanca with bitter humor. He’s a delightful character, extremely funny even now, and one who can step outside the conflict and provide commentary by virtue of his outside perspective, which makes his eventual rediscovery of his French patriotism even more impactful. He clearly adores Rick, and you get the feeling that it’s because he’s used to always being the smartest man in the room, and he appreciates having someone as cynical as him around who can understand his witty bon mots and riposte appropriately. Whereas Bogart plays Rick as a man who plays his cards close to his chest–another similarity with The Maltese Falcon is that you don’t know what’s actually planning until the very end–Renault wears his heart on his sleeve, until you finally realize that the patter and jokes and commentary and affected air of cynical detachment is covering up a deep, hidden discontent, one that he has managed to hide even from himself.

It’s really funny how many lines of dialogue in this movie I recognized just from the gestalt of pop culture. …

Edvard Munch being cheerier than usual

Women and the functioning of our institutions

Women Don’t Run? Election Aversion and Candidate Entry

Abstract: To study gender differences in candidate emergence, we conduct a laboratory experiment in which we control the incentives potential candidates face, manipulate features of the electoral environment, and measure beliefs and preferences. We find that men and women are equally likely to volunteer when the representative is chosen randomly, but that women are less likely to become candidates when the representative is chosen by an election. This difference does not arise from disparities in abilities, risk aversion, or beliefs, but rather from the specific competitive and strategic context of campaigns and elections. Thus, we find evidence that women are election averse, whereas men are not. Election aversion persists with variations in the electoral environment, disappearing only when campaigns are both costless and completely truthful.

And

Evidence for a Collective Intelligence Factor in the Performance of Human Groups

Researchers conducted a study to explore what makes groups work effectively together. The task involved designing an architectural project, first completed by individuals and then by groups. While an individual’s intelligence predicted how well they performed alone, the same wasn’t true for groups. Instead, a measure called “collective intelligence” (c) was found to be a much better indicator of group success.

The researchers examined several factors that might influence collective intelligence. Surprisingly, traits like group cohesion or motivation didn’t play a significant role. Instead, three key factors stood out:

1. Social Sensitivity: Groups where members were better at understanding others’ feelings and perspectives—measured by a test involving interpreting facial expressions—tended to perform better.

2. Turn-Taking in Conversations: Groups where everyone had a chance to contribute equally outperformed those dominated by a few voices.

3. Gender Composition: Groups with a higher proportion of women were generally more collectively intelligent, largely because women scored higher on the social sensitivity test.

These findings suggest that effective collaboration depends more on how group members interact and share ideas than on individual intelligence levels.

The second item above was so badly written that I got an AI to rewrite it, which it has done admirably.

Aristotle and human cognition

Poking around in Aristotle’s politics, he isn't so far from contemporary understandings of human cognition — that our remarkable capacity as a species driven by our enormous brain compared with other primates — drives our capacity to understand each other and thus to cooperate with the development of an ethical sense being conjoint with this. That it is only having built those collective foundations and the institutions within which they are built that our capability as a species takes off.

“It is thus clear that man is a political animal, in a higher degree than bees or other gregarious animals. Nature, according to our theory, makes nothing in vain; and man alone of the animals is furnished with the faculty of language. The mere making of sounds serves to indicate pleasure and pain, and is thus a faculty that belongs to animals in general: their nature enables them to attain the point at which they have perceptions of pleasure and pain, and can signify those perceptions to one another.

But language serves to declare what is advantageous and what is the reverse, and it is the peculiarity of man, in comparison with other animals, that he alone possesses a perception of good and evil, of the just and the unjust, and other similar qualities; and it is association in these things which makes a family and a city.”

Politics, Book 1, Chapter II, §10

HT: Paul Krugman (How Krugman gets time to watch so much great music while being a full time professor of the highest rank and writing two columns a week is beyond me. Anyway, he’s given up the column and taken to Substack! And he’s not charging.

Climbing the Ivory Tower: How Socio-Economic Background Shapes Academia

Ran Abramitzky, Lena Greska, Santiago Pérez, Joseph Price, Carlo Schwarz, and Fabian Waldinger

Abstract:We explore how socio-economic background shapes academia, collecting the largest dataset of U.S. academics’ backgrounds and research output. Individuals from poorer backgrounds have been severely underrepresented for seven decades, especially in humanities and elite universities. Father’s occupation predicts professors’ discipline choice and, thus, the direction of research. While we find no differences in the average number of publications, academics from poorer backgrounds are both more likely to not publish and to have outstanding publication records. Academics from poorer backgrounds introduce more novel scientific concepts, but are less likely to receive recognition, as measured by citations, Nobel Prize nominations, and awards.

The Benefits and Costs of Paid Family Leave

Buyi Wang, Meredith Slopen, Irwin Garfinkel, Elizabeth Ananat, Sophie M. Collyer, Robert Paul Hartley, Anastasia Koutavas, and Christopher Wimer

National paid family leave programs have been repeatedly proposed in the United States in recent years. To inform policy discussions, we provide a benefit-cost analysis of introducing such a program. We systematically identify high-quality, quasi-experimental studies on the impact of paid leave on infants and parents. Using the most conservative estimates or the mean estimates from this literature, we estimate that every $1,000 investment in paid parental leave would generate, respectively, $7,275 or $29,406 in present discounted net social benefits. We use these estimates to conduct a microsimulation of benefits and costs of two policy proposals with different eligibility and wage replacement rates. The first, a 4-week program, would have an initial fiscal cost of under $2 billion and net social benefits of $13 (conservative) or $55 billion (mean). The corresponding figures for the 12-week program are about 3.7 times larger, suggesting that either version would likely gener! ate high returns.

Bob Carr and AUKUS

From March 2024.

The sweetest words in the English language: I told you so.

French submarines, the first of which were scheduled for delivery in 2034 under a $90bn program with France’s Naval Group – before the contract was ripped up by the Morrison government – were lethal and affordable.

Now we know that the US is very reluctant to sell us Virginia Class nuclear powered SSNs under the AUKUS agreement.

The Result?

No Aussie subs in the 2030s and total reliance on the Yanks.

We are not a sovereign nation.

Predicting in theory what exists in fact

I love the story of the way the planet Neptune was discovered after an astronomer, noticing unusual perturbations of Uranus told people where to look. This week I discovered an even more striking example in a very different area. Many people with wide general interests know of the East African naked mole rat. That’s because it’s so unusual. It’s a eusocial species, meaning it lives in large colonies or cities with a substantial division of labour — like ants, bees, termites (white ants to us Australians), and of course us humangoes. (This newsletter is unapologetically by a humango, for humangoes, but I digress.)

However, virtually no one knew of mole rats in 1976 when their existence was predicted by an evolutionary biologist who wasn’t convinced by Richard Dawkins’ Selfish Gene and its discounting to nothingness Darwin’s suggestion that selection could take place at the level of the group rather than just at the individual level — thus explaining other-regarding preferences. (I don’t call this ‘altruism’ for reasons explained here.) In any event if you have other cool stories of phenomena being predicted ahead of their discovery, please share them in comments.

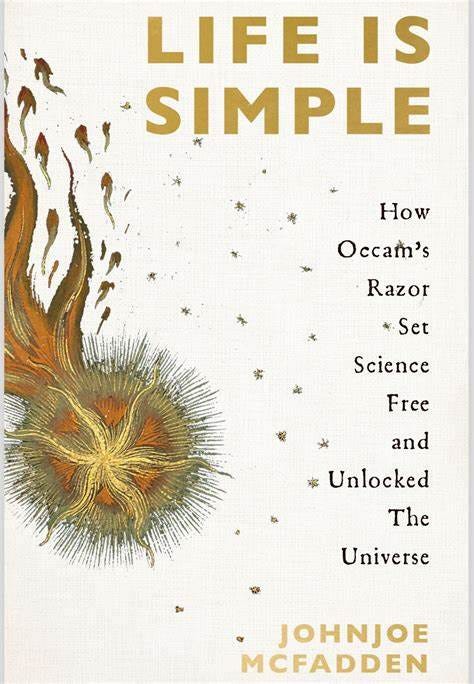

Johnjoe McFadden takes up the story:

Eusocial insects (a group that includes bees and ants) are characterised by complex social structures including division of labour, highly complex nests, often a single reproductive queen attended by sterile workers, and sophisticated forms of communication, such as the figure-eight dance of honeybees. Sterile workers at first sight appears to contradict the ‘red in tooth and claw’ principle of natural selection which would be expected to favour individuals who put their own interests first. Why should a worker ant abandon the option of reproducing itself in favour of helping its sister? The question goes to the heart of a puzzle in biology, especially in relation to our own species: altruism. Contrary to what might be expected from the principle of survival of the fittest, many animals, such as the eusocial insects, share resources and defences, but why?

The English evolutionary biologist William D. Hamilton (1936–2000) proposed a possible solution. Most eusocial insects share a peculiar inheritance system called haplodiploidy, in which males have only one, rather than two copies of all their genes, whereas females have the normal two copies. Applying Mendelian rules to this pattern of heredity ensures sisters share 75 per cent of their genes, rather than the usual 50 per cent typical for peas, humans or other animals and plants. Hamilton did the sums and discovered that a female often has a better chance of passing on her genes by helping her sister, the queen, reproduce, rather than producing her own brood. According to this theory, although worker ants or bees may appear to be altruistic, it is actually their genes that are in charge. The workers and their queen are both slaves to their genes.

What is most remarkable about this theory is that a single tweak to the simple Mendelian pattern of reproduction and heredity can generate vastly different creatures. This is of course a feature of any simple system. Whereas highly complex interconnected structures tend to be robust to perturbations, modifying the rules of a simple system, such as heredity, will reverberate through the entire system to generate large effects. Hamilton published his kin selection theory in 1964 and, although it was initially ignored, it eventually sparked the revolution in evolutionary biology that became known as socio-biology in the 1970s, particularly after the publication of Richard Dawkins’s classic The Selfish Gene in 1976.

Dick Alexander (1929–2018), curator of the Museum of Zoology at the University of Michigan, was not convinced by Hamilton’s theory. As an entomologist and expert on eusocial insects he pointed out that most species with single-gene copy adults, including many beetles, mites, whiteflies and other arthropods, are not eusocial; whereas termites, whose adults, like us, have paired copies of each gene, are. Both ants, termites and bees do however share the habit of building strong defensible communal nests. In a lecture at the University of Arizona in 1976 he presented an alternative theory that eusociality is caused by environmental, rather than genetic, factors. It is a simple theory and, like all simple theories, makes a tight prediction. It predicted that eusociality would arise, even in mammals, wherever there are ‘safe or defensible, long-lasting, food-rich nest sites’. He suggested burrowing rodents as possible candidates and the tropics as a likely location as burrows would be sealed tight against intruders beneath sun-baked soil yet have available food in the form of the tubers that store nutrients below the ground to survive bush fires.

After his talk, Alexander was astonished to discover that his theory had already and unwittingly been verified. After stepping down from the podium, a member of the audience, a zoologist called Terry Vaughan, approached him to point out that ‘Your hypothetical eusocial mammal is a perfect description of the naked mole-rat of Africa.’ Alexander had neither seen, nor even heard of, the naked mole-rat, but Vaughan showed him a dried specimen that he had collected during a sabbatical year in Kenya. Although discovered a century earlier, hardly anyone had studied the animal and, as far as Vaughan was aware, the only person then working on the obscure rodent was a zoologist called Jennifer Jarvis based at the University of Cape Town.

Naked mole-rats are not actually rats. They belong to a family of African rodents known as blesmols that inhabit a similar ecological niche to that of the gophers of North America. Jarvis had been studying the animals since her thesis project in 1967. In the 1970s she had tried to establish a captive colony in her laboratory in Cape Town, but had only ever been able to persuade a single female in the colony to breed. The penny finally dropped when, in 1976, she received a letter from Dick Alexander asking about the animals and telling her about his eusocial mammal theory. Jarvis confirmed that the naked mole-rat was indeed exactly the kind of animal that Alexander had predicted should exist.

Naked mole-rats are widespread in East Africa, where they are sometimes known as sand-puppies. About the size of a small mouse, they are completely hairless with loose skin and tusk-like teeth that are used for burrowing. They remain underground throughout their lives which are spent in dark burrows so, although they do have tiny eyes, they are nearly blind. As well as being of interest to evolutionary biologists, the species has caught the attention of medical researchers as mole-rats never develop cancer and can live extraordinarily long lives of thirty years or more. These physiological features inspired the publication of the naked mole-rat genome in 2011.

Oh, and I’m enjoying this book. You might too.

Heaviosity half hour

Arthur Miller on entertainment as vortex

I had written the rodeo scene to take place in a certain town, its name faded from memory now, far out in the desert. I had come across it one day with the two cowboy horse-hunters: a string of slatternly houses made of unpainted gray pine boards, and another string of bars, about eight or ten in all, facing an impromptu rodeo ring in front of a rough bleachers. Beyond the ring was a church atop whose steeple a wooden cross tilted over, ready to fall into the street, a reasonable symbol of what I was after in the film. The line of bars had one long dent in front where drunks had banged cars and trucks into them, men from the nearby wallboard plant who worked in clouds of white gypsum dust all day. Inside bullet holes showed in the ceilings and walls, with whole pockets dug out of some wooden bars by quick fire. It was the only town in Nevada where a man could legally carry sidearms, and a great many did, big forty-fives strapped to their thighs. During my Nevada time I had been there one Saturday night when the sheer fury of the customers was like a fever in the air, and I had to wonder if the grinding emptiness of their lives had driven them to want to kill or threaten to kill or be killed. It was never a question of robbery, just of two men starting a brainless argument that ended in shooting, a kind of mass sex, it seemed, with bloodshed as the climax of the rodeo itself.

As it turned out, we could not work in that town because there was insufficient water to supply cast and crew, and because of its distance from Reno and our hotels. We found another town, with better facilities and plenty of room for us: it had been deserted decades before by its entire population when some nearby mine gave out. Weathered signs were applied on the store windows or hung askew over the street. It was all very strange to think we were shooting where a real population had once lived, people who had doubtless had great hopes for a good life and now had vanished.

But another place where I had spent some time with my cowboy friends—a house owned by a Mrs. Styx—was used as Roslyn’s temporary Nevada residence. It overlooked one of the rare green valleys in that desiccated area, with some trees and enough good grass for a few cattle. Anticipating a need for more space in which to move the camera around, production people had sawed through the corners of the house to make them removable at a moment’s notice by turning a few bolts. In a morning a vegetable garden was set in place out front, as the story required, and shrubs planted. One quickly forgot these were all new. The oddness about it was that like demented gods, we had taken a reality and created a fake.

And I was finding it hard to remember that in reality Clark Gable was not the cowboy who had inspired the Gay Langland character. It was during this part of the shooting that the original cowboy suddenly showed up to look on for a few hours, and I could not help feeling disappointed by a certain thinness about him as compared to Gable’s more satisfying roundness and density. Of course I was part of Gable’s character, as I was not of the cowboy’s.

There was also something disturbing in the fact that the walls of the very house in which I had sat a few years before with the real cowboy and a girlfriend he had brought along could now be unbolted and simply slipped out of position to reveal an open sky. Perhaps the secret alarm in this was its echo of the willfulness of our way of constructing our lives, and deconstructing them, too.

I kept trying to rewrite the last few minutes of the film, which had never been quite right. Aware of the hopefulness with which I had conceived the story and my uncertainty about my future now, I still could not concede that the ending had to be what I considered nihilistic, people simply walking away from one another. At the same time, contrary to my story, I could not deny that a certain indeterminacy of life was really all these characters had to rely on. In fact, taking uncertainty to heart left them feeling free. Life betrayed, and that was all there was to it, but I willed it to be otherwise in this film. Besides, it could also have been true that they had found one another and stuck.

One afternoon Marilyn, with no evident emotion, almost as though it were just another script, said, “What they really should do is break up at the end.” I instantly disagreed, so quickly, in fact, that I knew I was afraid she was right. But the irony was too sharp: the work I had created to reassure her that a woman like herself could find a home in the world had apparently proved the opposite.

Briefly I wondered if this could be a call for help, but I could detect nothing in her eyes beyond a cool, professional look. I could no longer offer what I believed she could not accept. The terrible fact was that as she moved through the shooting she seemed at one moment all inwardness, not noticing anyone around her, and at the next wonderfully social with absolutely everyone she laid eyes on—as though the stream of her emotions had shattered into a spray of anger falling endlessly through her heart; it was impossible to sense at all what she was feeling and what her mood was until she spoke.

Huston at a certain point began to stir as the hours grew longer when she simply could not get ready to work. Her lifelong wrestling with the fact of time had thrown her to the mat finally, had nearly immobilized her now; she had always been one of those people for whom time is a sticky entanglement that they don’t want to touch, perhaps in denial that a past exists.

Huston seemed to have resigned himself after the first month or so of shooting, but now he took Paula aside and asked what she proposed to do about her charge. He had begun staying up all night at the craps table, losing immense sums and winning them back and showing his mettle that way, occasionally falling asleep in his chair behind the camera and losing track of which scene he was shooting. Chaos was on us all. He was working on sheer muscle now, his control amazing.

I thought he had been simply blanking out Paula’s existence for some weeks, refusing her intercession as demeaning and unprofessional. Her control over Marilyn was now so complete that Marilyn had moved from our apartment in the hotel into hers; Paula had finally won our long undeclared war. Still, this might clear the air, I thought, and free Marilyn to concentrate solely on the work as she now said she wanted to do. But I was under no illusions that any of us were really doing what we wanted to do; a force of pure destruction was thrashing around among us, beyond anyone’s control. I was only going through the motions of caring about the rest of the picture. It now seemed a hateful thing that had cost me too much, and I could only hope it would not turn out too badly. The one real dread I had was that Paula would accede too easily to Marilyn’s demands for more and more sleeping pills, but she promised she would not give in, and I tended to believe her because she was clearly in fear of a catastrophe herself.

One evening after dinner I walked to a small park near the hotel and sat on a bench watching eight young girls play tennis on adjoining courts. That people could still be doing something as simple as hitting a ball back and forth across a net seemed miraculous. The sheer good health of the girls drove tension out of me, just watching them take their untroubled deep breaths and wipe their wet pink upper lips and scream now and then. Longing to stretch out, I lay down on the grass propped up on one arm and soon fell fast asleep. I awoke in a silent city without traffic; the girls were gone, and it was a balmy three o’clock in the morning.

In the hotel’s casino Huston was shooting craps at a table with a glass of scotch in his hand, his bush jacket as crisply pressed as if he had put it on ten minutes before. He was behind twenty-five thousand dollars. He grinned and I grinned back. It did not seem important to him, although I knew he would find it awkward paying out that much. I went up to bed. In the morning at about seven I came down for breakfast, and he was still shooting craps, still with a glass of scotch in his hand. He had won back the twenty-five grand and was now trying to win more. His bush jacket looked as neat as it had before. Just thinking about standing up all night exhausted me all over again.

Metty’s worry that close-ups were showing Marilyn’s exhaustion finally forced matters to a head. Paula, now in control and thus unavoidably open to blame, quickly announced that Lee was at last coming out from New York. Such was Huston’s desperation that he very nearly welcomed this news. I certainly did, if only because Lee would now have to assume at least some direct responsibility for her unrelenting uncertainty as an actress in this role. Despite her utter reliance on his every word, he had managed to keep a safe distance through all her difficulties.

But there was another reason for welcoming his arrival: Marilyn had taken to paraphrasing speeches and omitting words and sentences. Huston, a writer himself, refused to accept her revisions, and to get the words right he had reshot sections as many as ten times. Looking on, I had assumed she was having memory lapses, but at one point she explained that the words in themselves were not important, only the emotion they expressed. In short, she was conveying Strasberg’s teaching as she understood it, a crippling attitude that I had seen in other actors and that I believed contributed to her unresolved tension in acting. Regarding the words as a hurdle, she was seeking spontaneity and freshness of feeling despite them instead of through them. If this approach occasionally did free her, it most often compounded her uncertainty when the actor opposite her was working on a different principle, of fidelity to the text, as of course the director was as well. Huston saw it all as arrant self-indulgence. I had asked how she and Paula proposed to work on classic roles, as Strasberg often predicted she would one day, when everyone was familiar with the texts and would not easily tolerate their being paraphrased. But it was obvious she was simply repeating what she had been given by high authority, and the pathos of it was heartbreaking, though no longer penetrable by me or anyone else. The fact was that she had done her best work with scripts, like Billy Wilder and I. A. L. Diamond’s for Some Like It Hot, from which she had not been allowed the slightest deviation because the comic dialogue had to be precise or would fail to work at all. That the same precision was necessary in a dramatic role, her first ever, seemed elementary, but with the encouragement of her mentors she was losing her way in an improvisational approach that might belong in an acting class but not in an actual performance.

In any event, Lee’s imminent arrival was at least something new happening, and as a onetime director himself, he would surely see that his teaching, if correctly understood, was incapacitating, and if misunderstood, must now be corrected.

With the schedule lengthening out and nothing I could do to cure things, my function on the film grew thin and more and more formal, and most of the time I spent alone. I thought of leaving, but Huston now and then wanted to talk about something in the script or make a change. One day we shot two silent scenes at Pyramid Lake, one of Gable-Langland teaching Marilyn-Roslyn to ride horseback, the other of them swimming. The two cottages where Bellow and I had lived—could it have been almost four years ago?—had once looked down across the lonesome highway upon the rocky beach and the primordial lake, but not anymore; a marina and fast-food stand had been installed, and motorboats aimlessly dashed about blasting the unearthly silence that in the script was supposed to help restore Roslyn’s hope for herself and her life. Everything seemed to symbolize; the motorboat drivers had to be asked to stop their engines while the scene was shot in this once enchanted place, observed by the chewing customers at the hot-dog stand that now stood a hundred yards away. I looked back along the highway for the phone booth where I had momentarily fainted once, but it was gone; there was probably a phone in the marina now. The booth’s absence kept me staring into the distance trying to revive the empty highway and the mutual idealization that had swept through me here.

It was hard watching her walk out of the water to be embraced by Gable when I could see no joy in her. As valiantly as she tried to appear in love, I knew her too well not to notice her distraction. But to approach her was to see her stiffen incredibly. I could only look on, praying that my estimate was wrong, but the marks of a living performance are moments of surprise, and it was a painfully willed performance, it seemed to me, the wild notes too worked out and premeditated. I was almost completely out of her life by now, but from my distant view the film seemed purely a torture for her. As it was for me when I thought back to my walk along the East River with Sam Shaw, when I had first imagined it as a kind of gift.

The whole make-believe business seemed detestable now, a destroyer of people, especially of those actors unable to settle for an ounce less than the full measure of truthfulness. Whatever it was that Paula and presumably Lee had been teaching her, she seemed less than ever able to feel, as opposed to thinking about her feelings, and thoughts are very hard to act. To be fair, her work in the film looked far more authentic to me in later years than it did during that bad time. I now marvel at how she managed, under the circumstances, to do as well as she did.

But at the time I wondered if acting had merely become a socially acceptable excuse for narcissism, an unholy absorption in the self rather than a joyous celebratory observation of mankind, which is all that can ever ennoble it. In my too many hours spent alone, the whole country seemed to be devolving into a mania for the distraction it called entertainment, a day-and-night mimicry of art that menaced nothing, redeemed nothing, and meant nothing but forgetfulness.

One evening I switched on the TV in my hotel room and found Nixon and Kennedy about to begin one of their presidential election debates. For some reason the country seemed to be continuing despite The Misfits. I ordered dinner and a bottle of whiskey and sat down to watch. There they stood, two more actors, but looking as uncomfortable as high school argufiers, Nixon apparently wearing his brother’s suit with the collar riding up his neck. How patently ambition-driven they were, these performers, each putting on a self-assured authority that he could not possibly have. Next to the TV the window showed blue night spreading over the everlasting mountains toward California, far easier to look at than the two on the screen. Weeks before, an arsonist’s forest fire out there had blackened the skies of two states and cut off Reno’s power, and our electricians had rigged a single cable six stories up to our room from a truck generator parked below in the street—the only lighted bulb in the city for Marilyn’s comfort. That had been good of them. Movie crews love the impossible, it makes them feel real.

Alone with the screen now, I caught something stale and prearranged about this debate. I could not get myself out of the movies, out of the theatre, out of the fake of this unbelievably important TV casting session by which the American people were to pick the star of their unending feature movie, trying to sense which scenes each would play well and which not so well, since there was no substantive difference between the candidates beyond a few cult words addressed to their partisans. Nixon seemed the foxy self-pitier who could also be tough, though Kennedy could probably threaten other countries better with that square Irish jaw and that good suit. But much of their performance depended on the script, which was always being rewritten. I hoped for Kennedy, of course, but mainly, I suppose, because we had read some of the same books.

Your report on Tasmania and the AFL Stadium, - excellent! Cilla Black and Dudley Moore - seems like a time of innocence and eye-games!

Hi Nick;

In case you've missed it, there's an article in the New Yorker and a section on the Political Gabfest podcast about a deliberative process in Bend Oregon on homelessness in that community. I happened to spend a few days in Bend in August 2024 - it's nothing more or less than a small pleasant inland USA city, with a river its best feature.

https://www.newyorker.com/news/the-lede/what-could-citizens-assemblies-do-for-american-politics

https://slate.com/podcasts/political-gabfest/2025/01/politics-legacy-president-jimmy-carter-elon-musk-donald-trump-maga-citizens-assembly-democracy