$4 for every $1 lift people out of grinding poverty

I was taken by this video and haven't been giving as much as I used to back in the days of my annual dinners which COVID put an end to. So given what I saw and the endorsement of the EA community, I’ll match the funds you donate (up to $2,500) and our combined funds will then be matched again (up to another $5,000).

How to get your donation quadrupled: Step 1. Click here. Step 2. Select 'I would like to choose how to allocate my donation' option. Step 3. Enter your donation amount alongside the GiveDirectly programs (three to choose from) and enter your details, Step 4. Finally, ensure you select “Nicholas Gruen’s Substack” in the 'How did you hear about us?' dropdown list.

Robodebt hero scores an honour for her early retirement and continuing sleepless nights

I’ve done some analysis and offered some commentary about people getting honours for just doing their jobs. Generally I’m against it. Then again what if you’re the only person among hundreds who actually did their job? Just doing her job was made near impossible for Colleen Taylor because she was one of a very few doing it while everyone else was doing the higher-ups business which was helping fit us up with the favoured narrative of the political higher-ups. Welfare recipients don’t really deserve to be treated with dignity.

And anyway, in true form, an act of real bravery — which has led to continuing sleepless nights — was good enough for the lowest award, with the highest of an AC going to Dan Andrews and Mark McGowan and also to Sam Mostyn who, obviously enough, required an upgrade to her AO on her transition to vice-regal office. Meanwhile Kathryn Campbell who was the secretary of the relevant agency while robodebt victims suicided remains two rungs up on Colleen with an AO.

In any event, here’s an interview with Colleen.

Taylor has been described in many ways — from “difficult to manage” to “a trouble-maker”. This week, Government Services Minister Bill Shorten called her a “true hero”.

If you ask the former public servant, who now lives a quiet life in regional Queensland, she was always just doing her job.

She only wishes it was enough to stop the punitive automated debt-collecting scheme before it was able to hurt so many people.

“You feel for the robodebt victims because their pain continues on,” Taylor told The Mandarin.

“They were all labelled criminals, and it was actually [the public service] sinning against them.

“To this day, I go through what I should have said: ‘Maybe I should have explained that more clearly?’ ‘Why didn’t I pick up on that?’ ‘Why did I say it that way?'”

It has been a big six years since Taylor retired earlier than planned from her job as a Centrelink compliance officer in July 2017. …

Commissioner Catherine Holmes noted in her final report that people like Taylor restored faith in an otherwise despairing lineup of APS witnesses who testified before the royal commission. …

“I won’t say it’s every day, but I have many, many sleepless nights and I have a lot of trouble sleeping thinking about robodebt,” Taylor said.

“Even now, when the news recently came up about the NACC [choosing not to investigate] some of the public servants involved — I was just in tears, and angry.”

Last week, the newly established federal corruption watchdog announced its decision not to probe six government officials the royal commission referred to the NACC. …

In Taylor’s view, justice demands the chief mandarins responsible for permitting robodebt to occur should be named and shamed.

“It’s a true indication of how obscene robodebt was that someone would get a [public administration] award for telling the truth. Truth was such a rare commodity that it’s come to this,” Taylor said.

“I suppose I’m called a whistleblower but, to my shame, I never went outside of the public service.”

When Taylor twigged something was not right with the automated debt notices being issued to people, she explicitly queried if sending a debt notice based on income averaging was equivalent to Centrelink stealing from welfare recipients.

The former compliance officer told the royal commission that it would have been “very rare” to use income averaging over the period of a PAYG summary to calculate how much debt (due to overpayment) was owed to government as robodebt did, because doing so would result in an inaccurate calculation. …

“I thought: ‘The people who are making these decisions don’t realise how this works in reality, and here’s someone who can tell them this is what’s happening, and this is why it’s so wrong’,” Taylor said.

“And you naively think: ‘If I could just explain it to them, then they’ll put a hold on it’.”

Taylor then escalated her issues with the debt notices to her director and assistant director, further flagging that most recipients of debt notices could not challenge them because the letters were being sent to addresses where people no longer lived.

“We are being asked to ignore evidence that no debt exists and to ‘collude’ in raising a debt where none should exist,” Taylor wrote in an email.

“That is, we are being asked to commit a fraudulent act.”

The great Jack Waterford on the incredible shrinking NACC

It’s a sorry tale.

… If one reads the uninformative statements from the commission since it began operations on July 1 last year, one might think that it had already put a number of matters before the courts and was knee deep in “ongoing” inquiries. But the matters coming before the courts have been largely rats-and-mice cases that were left over from the (also secretive, unaccountable and ineffective) law enforcement integrity apparatus.

The NACC has found no occasion for “teaching moments” at which it can use matters coming before it to tell public officials and the public about integrity in public administration. It has issued no reports, before or after successful prosecutions, apart from some media statements. It has conducted no public hearings.…

The commission is constrained by a cynical deal made by prime minister Anthony Albanese and Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus with opposition leader Peter Dutton, which had the affect of seriously winding back its power and, it is now clear, its effectiveness. Labor always had the numbers to get a tough NACC Bill through both houses of parliament, not least because Greens and Independents, including the teals, had played a stronger role than Labor in bringing the legislation forward.

Albanese is said to have calculated that if he could make the coalition a party to the legislation, if with a bit of “compromise”) the legislation would be more likely to endure a change of government. One concession was to require closed hearings (in limited circumstances the NACC can hold public hearings.) Reports from hearings are not disclosed to the public until after the completion of any consequential judicial proceedings when corruption findings have been made.

It was always the assumption that the fact of any NACC inquiries would not become public until after investigators had established, by private inquiries, whether there was fire behind the smoke of gossip and innuendo. If this prima facie point has been reached, the NSW model then sees open hearings held, and officials, and people accused of corruption, questioned in public. This has had the effect of putting a spotlight on poor administration, and causing administrative and cultural change even as hearings were continuing. Successful prosecutions, often years later, were almost incidental to the publicity effect. …

Nothing much has changed, and even less is intended to be changed, after Robodebt inquiry

One good public interest reason for revisiting many of the matters left undone by the Robodebt aftermath is that there has just emerged a new case which casts doubt on the idea that public service lawyers have reformed themselves in the wake of stringent criticisms by commissioner Holmes.

Public service lawyers claim that they are fully professional lawyers, answerable for their professional conduct to legal regulators and bound, on legal matters by service-wide professional principles, including the duty to be a model litigant. Robodebt showed lawyers allowing themselves to be intimidated by public service masters, to have connived in methods of avoiding serious gaps in the law to come into the open, and to have passively participated in schemes for avoiding facing important questions, never finalising adverse draft legal opinions, and declining to run appeals if there was a chance that tribunals would confront Robodebt lack of legal authority.

It was suggested that the legal regulators should examine the conduct of some of the in-house departmental lawyers for adherence to professional standards. It was a task that the regulators shirked — yet another way by which it can be said that the Robodebt report is full of unfinished business, in an environment where no public institution has the will or the desire to vindicate the public interest.

On Wednesday June 5, a Victorian Supreme Court judge dealt with a matter in which government lawyers for the Attorney-General’s department, for Home Affairs and the Australian Federal Police had collectively failed to fulfill a duty imposed on them both by the law and model litigant rules. It was a national security matter in which police and Home Affairs were trying to keep a convicted man behind bars, long after he had served his sentence, and it seems, had renounced terrorism.

Home Affairs were supporting their case with some computerised predictive systems. But they did not tender, as the law required, information which had the practical effect of discrediting these tests, based on university research. Almost everyone involved in the case had at some stage discussed the damning material, and most seemed to recognise the need to produce it. Advocates for the Attorney-General’s department had several conferences with their “client” – Home Affairs – at which the duty was raised. Some in Home Affairs had tried to get the report rewritten so it did not need to be produced. …

It would be far far better if the NACC took the matter over, linking it with the Robodebt inquiry, and the question of whether in-house lawyers are out-house lawyers, at least as far as respect for the public interest is involved. Heaven knows, it is time for Commissioner Brereton to come into the daylight and justify some of the money, and the hopes, vested in him. Let’s hope it does not take the time, and for such limited results, as the war crimes inquiry.

Speaking of unaccountability

No-one does it better than banks. ‘Too big to fail’ is a real thing during economic crises when payments are tightly coupled through the system. One goes down and suddenly, there are vast flow-on effects. Still, wiping out the equity holders in the bank as part of the bale-out would be a good start.

Anyway, I can't see how any of that applies to putting senior managers in jail. There are plenty of new managers to take over. Anyway, there you go. Was it Sinclair Lewis who said that it’s impossible to get a man to understand something that his salary depends on him not understanding? Plenty of higher ups are happy to put on a serious face and go along with an argument that makes no sense.

From inews, June 24, 2022

No senior banker went to jail over 2008; no HSBC banker was charged, let alone went to jail, when the bank admitted in 2012 to enabling the laundering of billions of dollars of drugs money for El Chapo and his Mexican Sinaloa cartel. …

The British government, in the shape of then-Chancellor George Osborne, went to bat, persuading the Americans – who were anxious to press charges – to back off. Osborne argued that they risked bringing down not only the bank but also the entire global financial system, such was HSBC’s size and reach.

No hard evidence was offered for this assertion. Yet in the end, the US authorities relented, and HSBC was fined $1.9bn, the largest amount in US history, and agreed to reform its ways under a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA).

HSBC admitted everything: how it had become a vast laundromat for the Mexican mob, even acknowledging that a tape existed on which a gang boss described HSBC as “the place to launder money”. Even by the dismal standards of its own industry, HSBC’s behaviour was truly shocking. …

According to the US Attorney General, the Sinaloa was the world’s number-one drugs trafficking organisation, responsible for distributing millions of tonnes of narcotics across the US. And for several years, it laundered its drugs proceeds via HSBC in Mexico. The cartel had boxes made to fit cashiers’ windows, so it could deposit more dollar bills more quickly; in one visit to the bank, one of Chapo’s associates handed over $933,000, in cash.

HSBC made its international network available to the Sinaloa, so its new Mexican customers were encouraged to open dollar accounts at HSBC Mexico’s branch in the Cayman Islands. Except there was no such physical branch – it was all done on desktops in the HSBC Tower in Mexico City. In a matter of months, 60,000 accounts were opened in Cayman – often without requiring ID or paperwork. …

While this was going on, HSBC management focused on making their bank even bigger, completing acquisitions around the world. Politicians fawned over them – the bank’s head for much of this period, Stephen Green, was made a life peer and a trade minister, a colleague of Osborne, in the UK government.

Chapo went to prison, as did many of his cronies, right down to the lowliest street dealers. They, like us when we commit wrongdoing, are not given the option of a DPA. Corporations and their chiefs, they are not the same: they are able to negotiate their way out of prison.

The bankers remain free – there was not even an official inquiry in the UK, despite HSBC being the country’s biggest bank. HSBC grew so big that even when it was found out to have sinned – or at least when its executives could, and perhaps should, have been interrogated in a court of law – that was not allowed to occur.

The then-US Attorney General Eric Holder explained about HSBC and its work for Chapo: “I am concerned that the size of some of these institutions becomes so large that it does become difficult for us to prosecute them when we are hit with indications that if we do prosecute – if we do bring a criminal charge – it will have a negative impact on the national economy, perhaps even the world economy.”

Square livestock was a thing

The chickenshit club I

So why are those on top so much less accountable? I think it’s not just that the governing class has grown more distinct, more entitled, more institutionalised, though there is that. There’s also been a hollowing out of incentives. Back in the day, a prevailing culture within agencies would have been professionalism. The word itself has a benign kind of valence, but I’m not using it for its benignity. The fact was that professional incentives implied a degree of independence — a degree of diffusion of power that is — all the way up the line. Today things are more managerial and managerialism concentrates power at the top. And managerial establishments tend to promote those lower down who are sound chaps and are not ‘mischief makers’ like Colleen Taylor.

And even from without, such organisations often face incentives that have become simpler as the media have grown more infantile and more powerful. In this world, if you prosecute and you don’t win, its easy for your opponents to paint you as chasing frivolous claims at great cost to the public and expense to the guilty acquitted. Oh, and the campaign orchestrated against you will be well funded and advised and endlessly, breathlessly beaten up on a propaganda operation media network near you.

From a 2017 book review:

In 2002, long before he became the most famous director of the FBI since J Edgar Hoover, James Comey, then the US attorney in Manhattan, issued a warning to the young lawyers on his staff. Do not join “the Chickenshit Club”, he said, meaning the prosecutors who only brought to trial cases they felt certain to win.

[S]ince that time, according to author Jesse Eisinger, the entire US Department of Justice appears to have ignored Comey’s admonition. The DoJ, which in the 1980s prosecuted more than 1,000 executives and jailed bankers such as Charles Keating over the $150bn savings and loan scandal, failed to imprison any CEOs after the 2008 crisis that cost Americans $13tn.

Eisinger, who borrows for his title Comey’s moderately profane appellation, details an unmistakable decline in the justice department’s willingness and ability to prosecute corporate crime. For the four years 2012-2015, white-collar cases made up just 10 per cent of the DoJ’s caseload — roughly one-half the share two decades earlier.

“The justice system is broken,” Eisinger concludes, adding that the DoJ in recent years “became fearful of losing and lost sight of its fundamental mission to make this country a just place”. For Eisinger, this largely unrecognised alteration in the American judicial system helps explain the political unrest that catapulted a former reality television star to the White House.

Along with the US government’s 2008 bailouts of the biggest banks, the failure to hold elites accountable for the financial crisis fuelled the public anger that led first to the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street movements and later to Donald Trump’s improbable rise. As Eisinger writes in his well-reported tale, this deference to corporate power now appears to be a permanent feature of the American landscape.

The chickenshit club II

The New York Times reviews the same book.

On April 27, 2010, Senator Carl Levin summoned the Goldman Sachs C.E.O. Lloyd Blankfein and his lieutenants before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations to answer allegations that the bank had misled investors prior to the 2008 financial crisis. Upon completing its investigation, Levin’s committee recommended that the Department of Justice open a criminal investigation into both Goldman’s business practices and the denials made by its executives before Congress.

Blankfein hired Reid Weingarten, a famous white-collar defense attorney who had once said of his work, “I feel like I’m in the French Revolution, defending the nobility against the howling mob.” Weingarten was a friend of Attorney General Eric Holder; his children went to Georgetown Day School with the children of Lanny Breuer, head of the criminal division of the D.O.J. Breuer, who had spent much of the previous decade at the elite Washington law firm Covington & Burling, assigned the case to Dan Suleiman, a former Covington associate. Weingarten pestered Breuer, saying, “Close this …case, will ya?” In 2012, the Justice Department announced that it would take no further action against Goldman or Blankfein. That’s how the game is played. (A year later, Breuer and Suleiman both returned to Covington.)

Why was virtually no one prosecuted for causing the 2008 financial crisis, which devastated the global economy and cost the United States almost nine million jobs? Some people think the fix is in: Bankers control the government, so they can get away with anything. Others claim that the banks did nothing wrong to begin with — or, alternatively, that there was insufficient evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that anyone in particular committed a crime. In this new book, the ProPublica reporter Jesse Eisinger tells a different story: Since the turn of the century, changes in the political landscape, the defense bar, the courts and most important the Justice Department have undermined both the ability and the resolve of America’s top prosecutors to go after corporations or their executives.

’Twas not always so. After Enron collapsed in 2001, federal prosecutors convicted the company’s accounting firm, Arthur Andersen, which surrendered its accounting license, as well as its three top executives. The former Enron C.E.O. Jeffrey Skilling is currently serving a 14-year prison sentence. By contrast, Goldman is still the world’s pre-eminent investment bank, and Lloyd Blankfein is still its C.E.O. Perhaps it was too hard to prove that the bank’s actions — which included betting against structured financial products while it was selling them to clients — violated the letter of the criminal law. Eisinger does not address that question head-on, which may disappoint some readers. His point, however, is that the Justice Department’s prosecutors didn’t try very hard — and the few who did were reined in by their politically appointed bosses.

Andersen was already collapsing because it had shredded its own reputation, but the business community and the corporate defense bar played up the idea that an overzealous prosecution had put thousands of people out of work. Bigwig defense lawyers like Mary Jo White (future chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission) claimed that Andersen proved that the Justice Department should go easier on companies. In the Obama administration, the idea that some companies are “too big to jail” was endorsed by both Breuer and Holder. Even the bank HSBC, which laundered hundreds of millions of dollars of drug money and illegally facilitated transactions with countries like Iran and Libya, got away with a fine.

This solicitous attitude toward corporations was part of a larger cultural shift in the business and legal world. Defending executives became an increasingly lucrative practice for elite law firms, which recruited star prosecutors from the Justice Department. Corporations accused of misconduct lawyered up, offering extensive internal investigations but erecting imposing defenses around individual executives. Banks cultivated plausible deniability, their internal oversight systems too feeble to pin responsibility on any individual; Goldman executives used the abbreviation LDL — “let’s discuss live” — to hide their traces. Prosecutors and regulators could either negotiate a modest settlement and declare victory or take on the daunting task of bringing actual people to trial — with the significant risk of losing. “A symbiotic relationship developed between Big Law and the Department of Justice,” Eisinger writes. Corporations got off paying symbolic penalties, defense firms raked in huge fees, and prosecutors earned P.R. victories — as long as everyone played along.

Increasingly, the prosecutors and the defense attorneys on opposite sides of the table are the same people, just at different points in their careers.

Conducting a criminal investigation of an executive isn’t just risky; in addition to jeopardizing a future partnership at a prestigious law firm, perhaps most important, it incurs “social discomfort,” especially for the well-mannered overachievers who now populate the Justice Department. No one wants to be a class traitor, especially when the members of one’s class are such nice people.

… There’s just one problem. While the “unelected permanent governing class” may have been willing to look the other way when highly paid bankers wrecked the economy, many of the workers who lost their jobs and families who lost their homes were not. Outside the Beltway, the fact that the Wall Street titans who blew up the financial system suffered little more than slight reductions in their bonuses only reinforced the perception that the “system” is “rigged” — with the consequences we know only too well. Many people simply want to live in a world that is fair. As Eisinger shows, this one isn’t.

An interesting discussion

A set piece recorded discussion on the golden rule sounds a little dull to me, but of course it depends how it’s handled and who’s doing the discussing. I enjoyed this discussion and thought Daniel Markovits was particularly provocative — of thought that is. I’d also never heard Carol Gilligan in action though I admire the turn late second wave feminism took with her towards ‘the ethics of care’ as I wrote here.

Two square pigs

Peter Dutton backs the square cow led energy renaissance

A good joke I heard in the podcast above is from Hannah Arendt.

It’s true that you have to break eggs to make an omelette, but you can break an awful lot of eggs and still not make an omelette.

Be that as it may, witness the latest manifestation of post-modern Maoism: in the tradition of perpetual culture war, Peter Dutton wants a culture war driven energy policy. As Bernard Keane writes, the policy is to undermine the economics of renewables — that pesky, far from perfect and left-wing form of energy.

In a saner world in which politicians were trying to make their own contribution to good policy and good sense from their ideological patch, Dutton’s embrace of nuclear energy could be a useful corrective to the foolishness of a regulated ban on nuclear energy and to the even greater foolishness of a transition to net zero based on renewables that looks impossible to deliver and which looks as doable as it does partly because right-thinking outfits like the CSIRO model the transition by assuming vast investment in the network appears from Mars — which is to say that new investment is treated as a sunk cost.

But then if this was a saner world, it wouldn’t have been the Liberals who destroyed carbon pricing and took us down this path in the first place. (And while I’m at it, the CIS has taken to describing current policy as a carbon tax by stealth. If only?)

But that’s not the game at all.

… Yesterday’s announcement by Dutton — so devoid of substance that even the press gallery’s fence-sitters derided its lack of detail — was really about creating a cover for the one solid Coalition energy policy that currently exists. That policy is to sabotage investment in large-scale renewable energy ….

[W]hy would you plan to invest in a large-scale renewables project if you know there’s a substantial chance … that a Dutton government would move to kill off funding both for renewables and for the poles and wires needed to move the power they produce and store to households and businesses? …

It’s important to understand that that’s not some minor collateral damage from Dutton’s embrace of nuclear power. It’s not some unintended consequence — it’s the entire point. … With investment in renewables already badly affected by the inability or refusal of state governments to expedite transmission construction, the opposition knows the kind of impact it can have on investor sentiment even when not in government. A major change of policy in Australia is never more than three years away.

… The fact that the Coalition wants to derail even investment currently under consideration illustrates just how obsessed with a culture war on climate change it, and its media backers at News Corp and Seven, really are.

It’s been 15 years since the Coalition turned its back on John Howard’s embrace of a carbon pricing scheme — a sensible, market-based solution to the challenges of climate policy. As the side of politics most supportive of market, rather than regulatory, solutions, the Coalition should have been the ones to champion a price-based mechanism to curb carbon emissions. Instead … it became the party of climate denialism and conspiracy theory around basic climate science. …

We’re all reporting this as a story about energy, about engineering, about public finance and costings and day-to-day challenges around delivering, operating and maintaining infrastructure. In fact it’s a culture war, pure and simple. And like any culture war, there’s no room for logic, evidence or reality — just enemies.

Collingwood Football Club and Racism

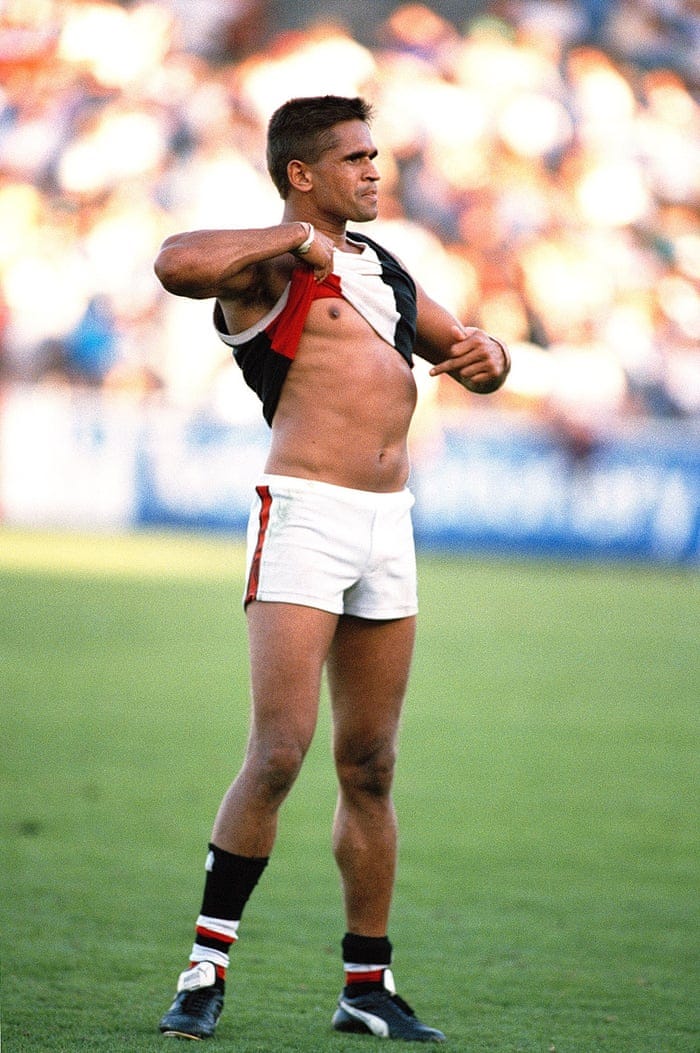

Yes, folks, this is a blast from the past. One of my early posts on ClubTroppo from 2005 and reprised here as a result of my watching the video above.

My team Collingwood has had an interesting involvement the modern social history of racism. At around the time of Pauline Hanson I used to argue that, though all the focus was on Pauline’s contribution to making Australia more racist, we were in fact becoming dramatically less so. At the grass roots it seemed to me that, at least in the big cities, things like the AFL code against racism offered a much more optimistic perspective.

The AFL code of conduct on racism grew out of a football match between Collingwood and St Kilda where, in the face of racist taunts from the Collingwood crowd, Aboriginal player Nicky Winmar would lift his jumper and point to his skin and gesture to the Collingwood outer at Victoria Park that it was their problem not his.

The hapless Collingwood Club President Colin Allan McAlister said that Aboriginal people would do much better for themselves as long as they conducted themselves like white people. Hmmm . . . . Dear oh dear!

I may well be wrong, but my impression of McAlister’s subsequent response was that he truly had a moment of revelation in which he realised how wrong he had been to say what he had said. (I’ve tried to get a good record of it on Google and I’m surprised I can’t get it quickly, but I could only find the story I linked to above).

There followed what seemed to me to be a genuine apology and McAlister’s participation in the establishment of the annual game between an aboriginal side and a non-aboriginal side. (A ‘black v white’ game seemed like something of a double-edged sword, particularly given how aggressively AFL is played, but it seems to have been a success.)

Two years after Winmar’s stand the great Aboriginal player for Essendon, Michael Long complained about racial abuse from St Kilda’s Damian Monkhorst and the AFL code of conduct on racism was brought in to great effect. Monkhorst is proud of his role in bringing it in! It has surely done much to make racism of both the casual and the hateful kind much less acceptable right through the mainstream of our society. It is a great thing. That picture of Winmar which started it all off must surely be one of the great pictures of the 1990s.

In the last year or so I’ve discovered two other facts of interest. I recall when I was a kid, Carlton’s Aboriginal half forward flanker Syd Jackson was reported for striking Collingwood half back flanker Lee Adamson. He told the Tribunal that Adamson taunted him with racial abuse. Though players rarely ‘dob’ each other in, and in fact often try to get those who have assailed them off, Adamson denied the claim. I think the Tribunal believed Jackson and he got off with a reprimand. I was pretty sure that Jackson was telling the truth – racial taunts were pretty standard. Adamson was a tough customer. But many years later, Jackson admitted that there was no racial taunt.

Then last weekend in the Age I read of a time eight years before Nicky Winmar’s stand.

As Jimmy Krakouer, near right, the mercurial North rover, prepared for the first bounce, Collingwood ruckman David Cloke ran by, tapped his head and delivered a message.

What he said was surprising given the culture of the time . . . . Cloke told Krakouer he could not control what was said from the other side of the fence, but if any Collingwood players resorted to racial abuse, Krakouer should tell him and he would deal with it.

Now 8 percent of AFL players are Aboriginal. I’ve been studiously trying to avoid the word while writing this. Its a cliche alright, but all those Aboriginal players I mentioned – they were mercurial! Fast, strong, and nimble as quicksliver. And – like Winmar’s defiance that day – a joy to behold.

Fukuyama gets on board with competitive middleware

It’s kind of obvious. It’s a good idea. The algorithms that determine what gets amplified and what is not should not be optimised for economic rent extraction. Dominant social media platforms are public utilities and should be treated as such. I’m not sure that free market provision is optimal, but it’s a whole lot better than the debauch we have now. Elon thought it was a good idea and it was one of the things he said he’d like to do with Twitter. Perhaps that’s why Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey said that he thought Twitter was a public utility and that the best private owner for Twitter was Elon. Anyway, Elon’s ardour for this particularly idea appears to have cooled.

Google, Facebook and Twitter have control over an enormous proportion of the nation’s political conversation. Increasingly, as these platforms have started moderating political content, their power has been distorting and degrading the quality of American democracy, says Francis Fukuyama, senior fellow at Stanford University’s Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) and director of FSI’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL).

“Big private corporations have neither the capacity nor the legitimacy to decide what types of information should be amplified or suppressed,” Fukuyama says.

In a white paper published by the Stanford Cyber Policy Center’s Working Group on Platform Scale, Fukuyama and his colleagues including Ashish Goel, Stanford professor of management science and engineering, and Stanford HAI International Policy Fellow Marietje Schaake, offer a novel proposal to deal with this problem: outsourcing content moderation to a layer of competitive middleware companies that would offer users of these platforms the ability to tailor their search and social media feeds to suit their personal preferences or objectives. “This would give users control over what they see rather than leaving it up to a nontransparent algorithm that is being used by the platform,” Fukuyama says.

The middleware proposal was featured as part of Stanford HAI’s “Policy and AI: Four Radical Proposals for a Better Society” conference, held November 9-10, 2021.…

The other proposals:

Universal Basic Income to Offset Job Losses Due to Automation

Thomas Friedman on Israel and Gaza

No friend of Israel should participate in this circus. Israel needs a pragmatic centrist government that can lead it out of this multifaceted crisis — and seize the offer of normalization with Saudi Arabia that Biden has been able to engineer. This can come about only by removing Netanyahu through a new election — as the Senate majority leader, Chuck Schumer, bravely called for in March. Israel does not need a U.S.-sponsored booze party for its drunken driver.

You wonder if the “friends” of Israel have any clue about the nature of its government. This government is not your grandfather’s Israel and this Bibi is not even the old Bibi.

Unlike any previous Israeli cabinet, this government wrote the goal of annexing the West Bank into the coalition agreement, so it is no surprise that it spent its first year trying to crush the ability of the Israeli Supreme Court to put any check on its powers. Bibi also ceded control over the police and key authorities in the Defense Ministry to Jewish supremacists in his coalition to enable them to deepen settlers’ control over the West Bank. They immediately proceeded to add settlement housing units in the heart of that occupied territory by record numbers to try to block any Palestinian state there.

This nightmare coalition is now in the process of ensuring that ultra-Orthodox young men will not have to serve in this war in equal weight with secular young men and women, who are exhausted by eight months of fighting. The army chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Herzi Halevi, told soldiers in Gaza over the weekend that there “is now a clear need” to draft the ultra-Orthodox to be soldiers to spare another deployment for “many thousands” of less religious reservists.

Israel’s relatively small combat officer corps has been so ground down, I cannot imagine how it could sustain a war in Lebanon.

Add it all up and you see a reckless act of economic, military and moral overstretch — committing seven million Jews to control more than seven million Palestinians (including two million Israeli Arabs) between the river and the sea in perpetuity.

That would be madness in a time of peace. In a time of war — a low-grade three-front war that could become a high-grade three-front war any day — it is insane. Israel is increasingly alone, because what ally would want to partner with that agenda?

And that is why I agree with every word that former Prime Minister Ehud Barak wrote in Haaretz last Thursday: Israel faces “the most serious and dangerous crisis in the country’s history. It began on Oct. 7 with the worst failure in Israel’s history. And it continued with a war that, despite the courage and sacrifice of soldiers and officers, appears to be the least successful war in its history, due to the strategic paralysis in the country’s leadership.”

Israel, added Barak, a former army chief of staff, is “risking a multifront war that would include Iran and its proxies. And all this is happening while in the background the judicial coup continues, with its goal of establishing a racist, ultranationalist, messianic and benighted religious dictatorship.”

Barak warned that if the current government is allowed to remain in power, Israel will not only find itself stuck in Gaza — with Hamas still able to fight and no Arab partner to help Israel out of there — it will also most likely find itself “in an all-out war with Hezbollah in the north, a third intifada in the West Bank, conflicts with the Houthis in Yemen and Iraqi militias in the Golan Heights and, of course, conflict with Iran itself.”

This extract is from the King's College London Policy Institute: (Declaration of interest. I’m a Visiting Professor there.)

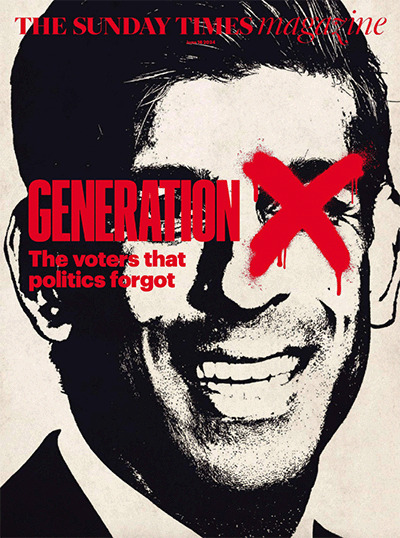

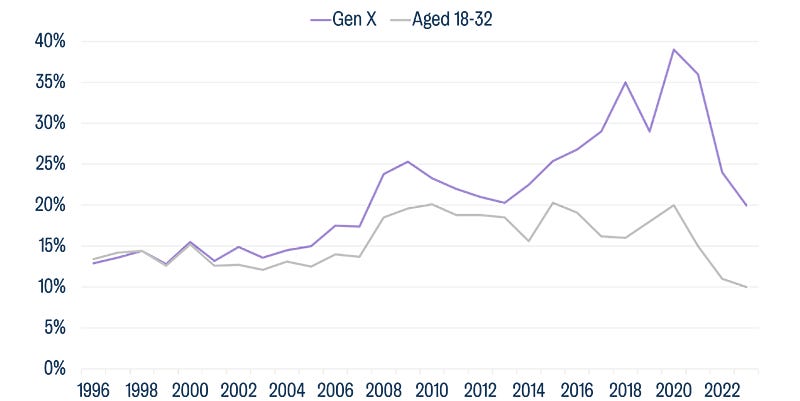

With the general election campaign now in the home straight, there’s inevitably much speculation about not just the outcome but why we’ve seen such dramatic shifts from the previous election. In a long read for the Sunday Times magazine, Policy Institute director Bobby Duffy looks at why it’s Gen X – not their more attention-grabbing generational neighbours – who are key to understanding why the Conservatives look set to lose the vote, if current polls hold true.

Gen X: the voters that politics forgot

Gen X have been called a generation so irrelevant that no one can even be bothered to hate them. And nowhere is their collective insignificance clearer than in political analysis. They’re barely ever mentioned, and instead, our national politics is set up as a battle between old and young.

But the reality is they’re the political middle ground no party can win without holding – and they’ll be the real source of the Conservative’s loss at the election, if the polls prove to be accurate.

Gen X have always been more electorally powerful than their “forgotten middle child” status makes them out to be. When you combine population size with turnout levels, there’s only a few percentage points between Millennials, Gen X and Baby Boomers.

They were also up for grabs. A third of Gen X say there’s no political party they feel particularly close to. It’s unusual to get to that stage of life without fixed loyalties: only one in five Baby Boomers feel the same.

So, their priorities should matter – and, believe it or not, they are interesting. Ipsos UK data on what issues will shape votes shows Gen X are most of all focused on health services: there is no route to convincing Gen X without a compelling vision for the NHS. But they’re not single issue voters: they also top the table on managing the economy and climate change. This makes sense given the multiple directions in which they’re pulled: a “squeezed middle”, battling with their own health, careers and finances, alongside concern about their elderly parents and children’s future.

They’re also a balanced blend of different outlooks on “culture war” issues, as the chart below shows. This points to an electoral strategy to avoid: there is no majority to be gained in Gen X — and therefore the electorate as a whole — by fighting a culture war. Focusing on “anti-woke” messaging plays well with the older base, but splits Gen X or just leaves them cold.

How the generations compare when asked about their views on cultural issues from trans rights to empire and free speech

Source: Policy Institute/Ipsos

There has been a lot of focus on how Millennials are not becoming more supportive of the Conservatives as they age – but Gen X have also not followed that pattern in recent years. It looked like they were going to, up to 2021, as the gap between them and the young grew – but support then just collapsed and the gap closed.

In contrast, Labour’s relentless “median voter” strategy could hardly be more Gen X-friendly. They are the ultimate bellwether constituency, and, much more so than “middle-aged mortgage man” or “Waitrose woman”, they are the political centre that parties should be aiming for.

Gen X were growing more conservative over time — until recently, when the gap started to close with the younger generation

Source: Ipsos Political Monitor

You can read the Sunday Times piece here (though I wouldn’t bother as I’ve tried to take advantage of their ‘free trial’ before and simply got lost in infinite IT do-loops.

Holding the conservatives accountable

Here’s an article in the Critic (which I think of as an anti-woke mag) arguing that a drubbing for the Conservatives would be a good punishment for what Rory Stewart devastatingly calls their lack of seriousness. There’s certainly some justice to the thought. And maybe it would end better than the alternative, but large majorities aren't necessarily a bed of roses. In fact it puts me in mind of an intriguing factoid which is the answer to this riddle. Which English speaking countries have managed to improve their standards of living since 1970 by dramatically less than other English speaking countries. Bonus marks if noone really understands. The answer is Britain and New Zealand. And one thing they had in common until New Zealand adopted multi-member electorates is that both countries had fewest checks and balances moderating the party with a lower house majority. Neither were federations and one had abolished its upper house, the other had turned it into a mostly powerless sinecure.

It would, Grant Shapps says, be bad news for British democracy if Labour won too large a majority next month. For a moment I wondered whether his words reflected a realisation that his own party had only been able to manage stable government this century when it was in coalition with someone else, but I don’t think this was his point.

It’s true that governments with small majorities are more constrained, but this isn’t obviously a good thing. Our years of Brexit deadlock were only broken once the government had a comfortable majority. And if you believe, as some on the right claim they do, that Britain needs planning reform and plenty of housebuilding, then a Labour government with a large majority is the likeliest route to those things. Certainly the Conservatives haven’t been able to deliver them with theirs.

But let me offer a different counterargument: it would be very good for our democracy for the Conservative Party to suffer a crushing defeat. The Conservatives have behaved terribly in government, and politicians, like children, need to know that their actions have consequences.

In 2019, British voters were faced with an unusual and appalling situation: a choice between two men both utterly unfit to be prime minister. Leaving aside Jeremy Corbyn’s political abilities — he could never persuade even Labour MPs that he ought to head a government — and his instincts — he would go on to suggest the British government had provoked Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — he had neither the temperament nor the intellect for the top job. So voters opted for what they perceived to be the lesser of two evils.

The result was that Labour paid a price for offering an unfit leader, and the Conservatives were rewarded. And that has been a bad thing. It told Tories that integrity in public life was optional.

Boris Johnson, of course, needed no encouragement on that score, but his weak-minded followers, in Parliament, on his staff, and in the media, thought they had won a free pass. “Voters don’t care,” we were assured, after each fresh scandal broke. Until it turned out that they did.

For all their later cries of anguish as Boris Johnson’s character was laid bare on the public stage, Conservatives knew exactly who he was when they made him prime minister. If the precise details of his downfall were pleasingly novel — who had “locks up the nation while hosting a series of wild parties” on their bingo card? — it was no surprise that he thought rules were for other people and lied as was convenient. This had been his entire career.

I hope my colleague Paul Goodman will forgive me reminding him of what was surely the greatest ever ConservativeHome editorial, which suggested that Johnson should be prime minister, but with rival Jeremy Hunt as a deputy, to handle the tedious business of running the country. Has any endorsement ever been less enthusiastic? …

And that’s just Johnson. Is there any Conservative out there who wants to argue that, since their party took sole charge of the country in 2015, they have been a good government? Four years spent arguing about Brexit followed by 18 months of a lockdown policy that was conspicuously more interested in pubs than schools, and then three years of infighting. So I’m happy for the party to be crushed. …

I want the Conservative Party from 2015 to 2024 to be a cautionary tale that politics professors whisper to terrify their students. Because if you can govern this badly, behave this badly, without any consequences, that would bode very ill indeed for our democracy. [You can, and it does. Ed.]

A different way to fund science

Competitive science funding often involves vast efforts at documenting a project (and if it’s real research there’s a fair chance there’s a fair bit of bullshit in it — because, like a good start-up, a good research program will often change quite markedly as new things are learned and new things come into view.) Then, because it’s so competitive, the chances of winning funding is often quite low.

And the process of ‘due diligence’ by those doling out the awards will often impose a risk aversion on the process, choosing safer, rather than riskier projects. And so the Hypothesis Fund was born.

What I also like about this is that it’s what I call ‘bottom up merit selection’. A big problem with elites is that in some sense it’s appropriate that they come to define what is elite, but over time that can become self-serving. This is evident in the less reality disciplined areas of human endeavour — art, social sciences, business, politics. We end up with ‘sound chaps’ rather than good ones. But there’s also some rude health that can come from decentralising the process by which merit is selected.

[S]tarting this month, [Kristala Prather] will … serve as a “scout” for an unusual new funding program. Prather’s mission is to spot colleagues with an intriguing research idea so embryonic it has no chance of surviving traditional peer review—and, on her own, decide to provide some funding. …

Prather’s new task comes thanks to the Hypothesis Fund, a nonprofit launched today that has an intriguing approach to funding climate change and health studies. Instead of inviting scientists to submit proposals, the fund will find recipients through 17 scouts—scientists, including Prather, chosen for their curiosity, creativity, diversity, and interest in the work of others. Each will get 12 months to award a total of $300,000 to fellow researchers with promising early-stage ideas.

After raising funds from donors such as Hoffman and Bill Gates, [Hypothesis Fund’s founder and CEO, Seattle entrepreneur David Sanford’s] board and scientific advisers recruited the first class of scouts. The unpaid volunteers are mostly midcareer scientists in fields such as infectious disease, geobiology, and neurobiology. … The fund will approve the grant as long as the work is novel, early stage, helps humans adapt to risks, fosters diversity, and can be completed within 18 months. Sanford hopes to plant 100 seed grants over 2 years with the money he’s raised so far.

The Hypothesis Fund isn’t the first to suggest empowering a network of scientists to hand out money to their peers. Scientists in the Netherlands have made a similar proposal, for example, but it has yet to get off the ground.

Heaviosity half hour

Alasdair MacIntyre on how lost we are on ethics

I loved this recent essay of MacIntyre. But then, to paraphrase my favourite comedian Stewart Lee, I agreed the fuck out of it. I wrote about MacIntyre’s great book After Virtue in an earlier newsletter.

I remember reading its opening pages in ANU Co-op bookshop when it first surfaced in 1981. They present a story in which science is destroyed by revolution and culture war. As they recover from this cataclysm people wander among the rubble finding artefacts from the old world from which they piece together what they take to be the science of the ‘ancients’. But it’s a jumble of artefacts and techniques. Noone really knows the big picture of what they’re doing because the traditions and practices by which things were connected up and related to each other are all fractured.

It struck me as a fantastic analogy for neoclassical economics. MacIntyre’s story is an allegory of what has happened to the West in throwing off a unified ethical system and, in his view ending up with a jumble of ethical artefacts all papered over by analytical philosophy which encourages ‘emotivism’ — the idea that all evaluative judgments and more specifically all moral judgments are nothing but expressions of preference.

Emotivism, for MacIntyre, departs from the classical and medieval traditions that ground ethics in a shared conception of the good life and the virtues necessary for human flourishing.

Anyway, after reading the essay I’ve extracted below, I think I described MacIntyre’s ideas slightly wrongly. For me the essence of his whole essay is the insistence that we understand ethics as something that is emergent from practical life, not abstract propositions. Here’s the money quote for me which you’ll find below.

We need to begin again and to do so by returning to the social context in which we learned the use of good and its cognates. What we first had to learn was how to make the distinctions between what we desire and the choiceworthy, and between what pleases those others whom we desire to please and the choiceworthy. We characteristically and generally learn—or fail to learn—to make these distinctions, as we emerge through and from the family into the life of a variety of practices: such practices as those of housework and farmwork, of learning Latin and geometry, of building houses and making furniture, of playing soccer and playing in string quartets. What we can learn only in and through such practices is what the standards of excellence are in each type of activity and how our desires and feelings must be disciplined and transformed and our choices guided by the standards of excellence in each type of activity if we are to achieve such excellence and through it the goods internal to each type of practice.

As I read this I also thought of Michael Polanyi who noticed that in every realm of life the things that can be made explicit are built on a tacit layer which is culturally learned from infancy. It seems to me that other ethical traditions presume that the action is in what can be made explicit and I think that’s completely wrong. Anyway, what would I know?

The other killer quote is this one which follows his elaboration of the perceived contradictions between Kantianism and Utilitarianism:

And it is in negotiating their way between such moments, both in private and in public life, that the characteristic skills of those who are socially and politically successful are exhibited. What we have then is a morality whose oscillations and contradictions show it to be in a state of disorder, but a kind of disorder that enables it to function well as the ideology of our present social, political, and economic order.

He doesn’t drive home the point in this essay, but he does in After Virtue, that the successful in the modern world are those who can inhabit the contradictions of our society — those who can participate with all seriousness in a strategic retreat that agrees that ‘honesty’ or ‘serving the Australian people’ is a core value and then returns to work on Monday to participate in some activity that is a complete travesty of these values — without batting an eye, indeed, without noticing. As he puts it devastatingly in After Virtue:

In any society which recognized only external goods, competitiveness would be the dominant and even exclusive feature… We should therefore expect that, if in a particular society the pursuit of external goods were to become dominant, the concept of the virtues might suffer first attrition and then perhaps something near total effacement, although simulacra might abound.

Over to Alasdair MacIntyre. I’ve edited from my own copy in which I’ve bolded some passages and added a comment or two in [square brackets] which I’ve left in in case it’s of use to you.

How I Discovered That, by the Standards of Contemporary Academic Philosophy, Thomist Claims Must Be Problematic

From 1945 to 1949 I was an undergraduate student in classics at what was then Queen Mary College in the University of London, reading Greek texts of Plato and Aristotle with my teachers, while also, from 1947 onwards, occasionally attending lectures given by A. J. Ayer or Karl Popper, or by visiting speakers to Ayer’s seminar at University College, such as John Wisdom. Early on I had read Language, Truth and Logic, and Ayer’s student James Thomson introduced me to the Tractatus and to Tarski’s work on truth. Ayer and his students were exemplary in their clarity and rigor and in the philosophical excitement that their debates generated. And I became convinced that the test of any set of philosophical theses, including those defended by Thomists, was whether it could be vindicated. In and through such debates. Yet I also had to learn—and this took a little longer—that in the debates of academic philosophy in the twentieth century no set of theses is ever decisively vindicated.

To excel as a contemporary academic philosopher is a matter of the quality of one’s analytic and argumentative skills, especially in their negative use to expose failures in the distinction-making of others or gaps in their arguments, together with an ability to summon up telling counter-examples. Conceptual inventiveness is also valued. Excellence in the exercise of these qualities is compatible with holding different and incompatible sets of beliefs about which of the various philosophical positions in contention in one’s own specialized area is to be regarded as true and rationally justified, including those positions in contention over how truth and rational justification are to be understood. Disagreement on fundamental issues is in practice taken to be the permanent condition of philosophy. The range of continuing disagreements is impressive: realists versus antirealists in respect of mathematical, moral, perceptual, and historical judgments; dualists versus materialists in the philosophy of mind; utilitarians versus Kantians versus virtue theorists in ethics; Fregeans versus direct reference theorists in the philosophy of language; and a great many more. Add to these a range of disagreements in religion and politics that, themselves non-philosophical, are closely related to philosophical disagreements: theists versus atheists, conservatives versus liberals versus libertarians versus Marxists. …

How I Discovered from Sartre and Ayer That Thomist Claims Are Problematic

Thomism had also become problematic for me for another reason. The Communist Party at Queen Mary College had introduced me to the texts of the Marxist canon, and I had become and to this day remain convinced of the truth and political relevance of Marx’s critique of capitalism and of his historical insights …. To how much else of Marxism I was thereby committed I was unclear. … Since one thing on which Marxists and Thomists seemed to agree was that Marxism and Thomism were incompatible, I found myself confronting yet another set of question marks. Nonetheless it was on the basis of Marxist insights into the nature both of morality and of moral philosophy that I began to formulate another, more constructive kind of question.

Marx and Engels had argued that every morality is the morality of some particular social and economic order and that every moral philosophy articulates and makes explicit the judgments, arguments, and presuppositions of some particular morality, either in such a way as to defend both that morality and the social and economic order of which it is the expression, or in such a way as to undermine them. And my acknowledgment of the truth of this thesis was reinforced by my encounters with social anthropology, especially first with the work of Franz Steiner and later with that of Rodney Needham. I therefore asked: What is the distinctive morality of this social and economic order that I inhabit, and how does contemporary moral philosophy stand to that morality? And in pursuing an answer to this question I was guided not only by Marx and Engels but also by John Anderson, who had urged that, if we were to understand social institutions and relationships, we should ask not what function or purpose they serve but to what conflicts they give expression. This suggested that both the morality and the moral philosophy of the present age are best understood as milieus of conflict, sites of disagreement. But those disagreements find significantly different expression in the arenas of philosophical debate on the one hand and in those of everyday moral and political practice on the other.

In philosophical debate, utilitarianism and Kantianism are presented, with some rare and sophisticated exceptions, as incompatible and rival standpoints. To adhere to some version of one is to be at odds with every version of the other. But in many areas of the everyday life of modernity what we find instead is an oscillation between those two standpoints and a moral rhetoric designed to disguise that oscillation. So there are moments in which principles are laid down without qualification and moments in which exceptions to those principles are justified in the name of either the maximization of prosperity or the maintenance of public security. And it is in negotiating their way between such moments, both in private and in public life, that the characteristic skills of those who are socially and politically successful are exhibited. What we have then is a morality whose oscillations and contradictions show it to be in a state of disorder, but a kind of disorder that enables it to function well as the ideology of our present social, political, and economic order.

Yet although I had come to recognize this as a result of reflecting on the Marxist critique of morality, I had also had to acknowledge that within the communist movement there was to be found much the same oscillation between quasi-Kantian attitudes and a consequentialism that parodied utilitarianism, and this not only in the brutal and corrupting ethics of Stalinism but also in the ethics of Stalinism’s Marxist critics. Marxism as a form of practice too often suffered from the same lack of moral resources as the social order that it aspired to replace, and this unsurprisingly, since it had been generated from within that social order. It was with the rise of the New Left in Britain, after the suppression of the Hungarian Rising of 1956, that the question of whether and how this defect in Marxist theory and practice could be remedied became urgent. But what were the resources needed to remedy it? I was able to answer this question only by considering further not only the issues posed by Kantianism and utilitarianism but also those raised by the disagreements between Thomists on the one hand and Ayer and Sartre on the other, concerning the nature and status of reasons for action. And to make progress with either of these sets of issues I had to look in a different direction, and my narrative has to move backwards in time.

Two Lines of Thought About the Meaning and Use of Good

Two opposed lines of thought about the meaning of the word good and its cognates had been developed in English-speaking philosophy since the 1930s. One of these finds its first formulation in Ayer’s Language, Truth and Logic in 1936. To call something good or bad is to express one’s feelings for or against it. To evaluate is to approve or disapprove. … To say of something that it is good is both to commend it and to urge those whom one is addressing to do so as well. …

Viewed in the light cast by Ayer and Stevenson, intuitionist moral philosophers turn out to be under the illusion that they are asserting moral truths when they are in fact doing no more than expressing their own individual feelings and attitudes. They suffer from a lack of self-knowledge. The problem was that this mistake by some English moral philosophers seemed to have its roots in the general moral culture of their time and place. For while, so far as I could judge, Ayer, Stevenson, and other expressivists had provided a compelling account of the characteristic uses to which moral judgments were now put in a particular culture, they had taken themselves to have provided an adequate account of the meaning of moral and evaluative sentences as such, whatever the culture. Yet the meaning of those sentences was such that they at least appeared to give expression to some impersonal standard of judgment to which appeal was being made. Meaning and use had, so it seemed, come apart, something on which the current philosophy of language shed no light. How might this have happened? …

This second line of thought began by taking seriously J. L. Austin’s injunction to begin with lexicography, to accumulate a wide range of different types of examples of the relevant expressions. Those who do so find themselves also following Aristotle—and this is no accident. Austin’s habits of thought were in several ways Aristotelian and certainly so in recognizing the multiplicity and the heterogeneity of our uses of good, better, bad, worse, and their cognates. We speak of bad kings and good jam, of a good day at the races and a bad holiday in Casablanca, of a good time to go on a spree and a bad way to do it, of someone’s being good at tennis or good for nothing. … Austin himself took there to be an irreducible and inescapable heterogeneity here. But Aristotle had identified a unity underlying that heterogeneity, and the clue to that unity was supplied by Peter Geach. In 1956 Geach had pointed out that good and bad are noun-dependent or noun-phrase-dependent adjectives and that well and badly are correspondingly verb-dependent adverbs. What it is for an X to be good depends upon what an X is, so the criteria of goodness in a king are very different from those of goodness in jam. And what it is to X well depends upon what X-ing is, so the criteria by which someone who plays tennis is judged to have played well or badly are not the same as those by which someone who shoes horses is judged to do so well or badly. And so we take a first step toward answering the question: What makes these various uses of good more than puns?

Here we need to bear in mind the distinction between attributive and predicative uses of good, as W. D. Ross originally formulated it, together with Geach’s thesis that good is essentially attributive, that to be good is always to be a good someone or something, and that predicative uses of good can be translated into attributive uses. We speak of “good parents” but also of “good burglars,” of “the best athlete in the games” but also of “the best forger still at work.” It matters therefore that we can always ask, “Is it good for someone to be a good parent?” and “Is it good for someone to be a good burglar?” and what we learned from Geach is that to ask these questions is to ask, “Is a good parent a good human being?” and “Is a good burglar a good human being?,” questions that can be answered only by first answering the question “What is it to be a good human being?”

It is at this point that this line of thought has sometimes been thought to encounter insuperable difficulties. That there are criteria independent of our choices, feelings, and attitudes governing our applications of “good parent,” “good burglar,” or for that matter “good boxer” or “good violinist,” is difficult to deny. For in each area, drawing on Aristotle’s thesis that to be a good X is to excel in the activities characteristic of an X, we can say what it is to exhibit such excellence as parent, as burglar, as boxer, as violinist. But, many have urged, any analogy between goodness as attributed to these and goodness as attributed to human beings breaks down. There is, they argue, no set of activities characteristic of a human being, as there are activities characteristic of parents, burglars, boxers, and violinists. Hence it was to be argued by Hampshire and by Berlin, following Austin, that there is no such thing as the good life for human beings, no such thing as the human good.

To this it can be replied that there are indeed many different ways of leading a good human life, but that there are at least four sets of goods that are characteristically needed by every human individual if she or he is to flourish. First, without adequate nutrition, clothing, shelter, physical exercise, education, and opportunity to work no one is likely to be able to develop his or her powers—physical, intellectual, moral, aesthetic—adequately. Second, everyone benefits from affectionate support by, well-designed instruction from, and critical interaction with family, friends, and colleagues. Third, without an institutional framework that provides stability and security over time a variety of forms of association, exchange, and long-term planning are impossible. And fourth, if an individual is to become and sustain her- or himself as an independent rational agent, she or he needs powers of practical rationality, of self-knowledge, of communication, and of inquiry and understanding. Lives that are significantly defective in any one of these respects are judged worse, that is, less choiceworthy, than lives that are not. These goods are goods without which excellence in activity is often impossible, and so the key to our various uses of good with regard to them is a shared conception of excellence in activity, of what it is to live virtuously.

Thus on any version of this line of thought—and there are different versions of it, for example, Philippa Foot’s naturalism and Iris Murdoch’s Platonism—there are standards independent of our feelings, attitudes, and choices by which we may judge whether this or that is choiceworthy, whether this or that is good to choose, to do, to be, to have, to feel. And every version is in conflict with the view that our evaluative uses of good, unless in a linguistically degenerated culture, are no more than expressions of or determined by our feelings, attitudes, and choices.

This radical disagreement concerning how our uses of good are to be construed is of course closely related to the disagreement that I identified earlier concerning the nature of reasons for actions, one in which Thomists were at odds with Ayer and Sartre. What it means to say that, in giving a reason for doing this rather than that, we are identifying some good that will be achieved by doing this rather than that depends on whether we understand good in expressivist or in other terms. Only if our uses of good are governed by standards independent of our feelings, attitudes, and choices can something like the Thomistic account of reasons for action be justified. So how are the issues between these two incompatible and antagonistic lines of thought to be resolved?

How at the Level of Theory the Debate Between the Protagonists of These Two Lines of Thought Is Interminable and Inconclusive

Someone disposed to find credible the account of the condition of academic philosophy that I advanced earlier would, without knowing any of the facts about the subsequent debates concerning the use of good, predict that neither side would be able to provide conclusive arguments for its own view and against the other, except by its own standards. And so it turned out. For this disagreement was integrated into the longer and continuing quarrel between self-styled moral realists and self-styled moral antirealists, a disagreement in which the contending parties have enriched the statements of their rival positions by drawing on discussions of realism and antirealism in other areas. And, just as in those other areas, the debates between moral realists and moral antirealists have had no decisive outcome. …

The philosophical interest resides in the detail of the arguments. But what emerges from that often-instructive detail is the large fact that, given the shared understanding of moral thought and practice presupposed by the two contending parties, and given their philosophical methods, neither party has the resources to defeat the other.

This is true more generally. Expressivists, whether followers of Alan Gibbard or Simon Blackburn or the earlier emotivist writers, have been able without notable difficulty to accommodate somehow or other every objection advanced against them. And a variety of anti-expressivists have been able equally easily to fend off the objections advanced against them. Each remains deeply convinced of the errors of the other. Both would regard it as intolerably frivolous to suggest that one should choose one’s side by flipping a coin. But how then is one to decide?

How It Is Only at the Level of Practice That We Can Become Aristotelians

We need to begin again and to do so by returning to the social context in which we learned the use of good and its cognates. What we first had to learn was how to make the distinctions between what we desire and the choiceworthy, and between what pleases those others whom we desire to please and the choiceworthy. We characteristically and generally learn—or fail to learn—to make these distinctions, as we emerge through and from the family into the life of a variety of practices: such practices as those of housework and farmwork, of learning Latin and geometry, of building houses and making furniture, of playing soccer and playing in string quartets. What we can learn only in and through such practices is what the standards of excellence are in each type of activity and how our desires and feelings must be disciplined and transformed and our choices guided by the standards of excellence in each type of activity if we are to achieve such excellence and through it the goods internal to each type of practice. [The undecidable foundations. Polanyi's tacit foundations.]

So long as our desires have not been disciplined and transformed in the relevant ways, our uses of good and of cognate expressions will tend to be what expressivist moral philosophers have taken them to be, and our choices will give expression to our feelings and attitudes. … So everything turns upon what we have been able to learn from the kind of practices in which we have engaged and on the nature of the particular moral culture or cultures in which we have participated. Understood in this light the philosophical quarrel between the two lines of thought that I sketched rests on a misunderstanding. It is not that we have two rival philosophical representations of one and the same subject matter but that we have two different subject matters, two different types of moral culture, an older one whose objectivist idioms and judgments are grossly misrepresented by expressivism, and one whose moral vocabulary exhibits just that blending of non-expressivist meanings and expressivist uses that had forced itself on my attention a good deal earlier, a blending characteristic of the dominant moral culture of advanced modernity.

Consider now some further aspects of a practice-based understanding of goods, virtues, and rules. The identification of a variety of types of goods poses the question: What place should we give to each type of good in our lives? And it is no accident that this question is framed in terms of “we” and “our,” rather than “I” and “mine.” For this is a question that I can only hope to ask and answer with good reason if I ask and answer it in the company of trusted but critical others, others to whom I recognize that I am bound by certain unconditional commitments—commitments not to harm the innocent, to be truthful, to keep our promises, commitments that allow us to reason together without the distortions that arise from fears of force and fraud—and this for at least two reasons. First, it is only in and through such interaction with trusted but critical others that our practical reasoning is tested, so that our evaluations become less one-sided and partial and less liable to distortion by our not always conscious hopes and fears. Second, it is only insofar as we direct ourselves toward common goods, the common goods of family, neighborhood, school, clinic, workplace, and political community, that we are able to achieve our individual goods. [This is what I call the ‘ground truthing’ element. Without others helping craft our own self-evaluation we can’t escape solipsism.]

We learn what place in our individual and common lives to give to each of a variety of goods, that is, only through a discipline of learning, during which we discover what we have hitherto cared for too much and what too little and, as we correct our inclinations, discover also that our judgments are informed by an at first inchoate but gradually more and more determinate conception of a final good, of an end, one in the light of which every other good finds its due place, an end indeed final but not remote, one to which here and now our actions turn out to be increasingly directed as we learn to give no more and no less than their due to other goods.

This discovery of a directedness in ourselves toward a final end is initially a discovery of what is presupposed by our practice, as it issues in a transformation of ourselves through the development of habits of feeling, thought, choice, and action that are the virtues, habits without which—even if in partial and imperfect forms—we are unable to move toward being fully rational agents. …

To have become such an Aristotelian is to have found good reasons for rejecting both utilitarianism and Kantianism. What renders any form of consequentialism unacceptable is the discovery of the place that relationships structured by unconditional commitments must have in any life directed toward the achievement of common goods, commitments, it turns out, to the exceptionless, if sometimes complex, precepts of the natural law. What makes Kantian ethics unacceptable is not only that our regard for those precepts depends upon their enabling us to achieve our common goods but also that the Kantian conception of practical rationality is inadequate in just those respects in which it differs from Aristotelian phronēsis or Thomistic prudentia. Note, however, that these grounds for asserting that there are conclusive reasons for rejecting both utilitarian and Kantian ethics are Aristotelian grounds. Take away the Aristotelian premises from which this assertion is derived and it will cease to convince. Unsurprisingly, therefore, it lacks force precisely for those against whom it is directed, utilitarians and Kantians.

It is therefore of some importance that in arriving at a certain kind of Aristotelian standpoint I was not taking up one more theoretical position within the ongoing debates of contemporary moral philosophy. It is because I have been thought to have done just this that I have been unjustly accused of being one of the protagonists of so-called virtue ethics, something that the genuine protagonists of virtue ethics are happy to join me in denying.

But what then is it to adopt this kind of Aristotelian standpoint? There are at least three aspects to such a change of view. First, it enables one from a standpoint outside academic moral philosophy, that of an older tradition of moral practice, to understand why such moral philosophy was condemned to become what it has become, a scene of theoretical disputes between fruitlessly contending rival parties. …

Second, it is to adopt a standpoint that enables individuals, by situating themselves within such a mode of social practice, to make intelligible features of the narratives of their own lives and of the lives of others that will otherwise remain opaque, confused, disguised, or trivialized. A basic Aristotelian thesis is that only insofar as we understand our individual and common lives as potentially directed toward the achievement of goods and of the good through the exercise of the virtues are we able to identify the various types of frustration, misunderstanding, and failure by which our lives are marked.

Third, just as Aristotelian moral and political theory provides us with resources for interpreting and redirecting our practical lives, so too our practical experience provides us with reasons for criticizing and sometimes rejecting some of Aristotle’s own concepts, theses, and arguments. We learn to identify that in Aristotle which derives from the limitations and prejudices of Athenian and Macedonian elites. …

How from the Standpoint of Aristotelian Practice Contemporary Academic Moral Philosophy Appears Defective as a Mode of Inquiry

The conception of moral philosophy at which I had thus arrived put me at odds not only with the standpoint dominant in contemporary moral philosophy but also with the established analytic understanding of how philosophical inquiry should proceed. For on the view that I have found myself compelled to take, contemporary academic moral philosophy turns out to be seriously defective as a form of rational inquiry. How so?