Ezra Klein on what’s wrong with Donald Trump

Pretty interesting essay from Ezra Klein on Donald Trump’s signature lack of disinhibition. which you can listen to him read on his podcast or read in the NYT.

We had the language to talk about what was happening to Joe Biden. … And so we did talk about it. We spoke about it relentlessly. We’ve never had good language for talking about Donald Trump. We’ve never had good language for talking about the way he thinks and the way in which it is different from how other people think and talk and act. And so we circle it. We imply it. I don’t think this is bias so much as it’s confusion. …

You may have heard of the big five personality traits: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness and neuroticism. … Some of the newer personality frameworks name the other side of the spectrum, too. So to be low on neuroticism is to be high in emotional stability. To be low on extroversion is to be introverted. And to be low on conscientiousness is to be disinhibited. To be very low on conscientiousness is to be very high on disinhibition. And that is Donald Trump.

He doesn’t mention it, but, as I understand it, this is a fairly well accepted marker of psychopathy. (Not that I’ve got anything against psychopaths. Well, that’s not true. Bad psychopaths can be very bad. So I guess we just have to hope.)

The progressive retreat

Quite a good summary of the way in which progressive politics somehow fluffed its moment of ascendancy. With bad ideas. It’s a long post which you can read for yourself, but I’m broadly in agreement with it on the first three bad ideas — though I’d probably be more poncy in my way of expressing it. And regarding the first, I think every day that if the Democrats had taken a leaf out of the ALP’s book and actually capitulated on stopping unauthorised immigration (you know, what the people wanted), they’d be sailing back into the White House. On the other hand in that case, the Democrats might have been polling sufficiently well to avoid the discomfort of removing a senile president from running again.

So how did the progressive moment fall apart, seemingly at the moment of its greatest triumph? It is not hard to think of some reasons.

1. Loosening restrictions on illegal immigration was a terrible idea and voters hate it. When Joe Biden came into office, he immediately issued a series of executive orders dramatically loosening the rules for handling illegal immigrants. This was rapturously applauded by progressives as exactly what was called for. …

2. Promoting lax law enforcement and tolerance of social disorder was a terrible idea and voters hate it. In the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd and the nationwide movement sparked by it, the climate for police and criminal justice reform was highly favorable. But Democrats, taking their cue from progressives, blew the opportunity by allowing the party to be associated with unpopular movement slogans like “defund the police” that did not appear to take public safety concerns very seriously.

At the same time, Democrats became associated with a wave of progressive public prosecutors who seemed quite hesitant about keeping criminals off the street, even as a spike in violent crimes like murders and carjacking swept the nation. This was twinned to a climate of tolerance and non-prosecution for lesser crimes that degraded the quality of life in many cities under Democratic control. San Francisco became practically a poster child for the latter problem under DA Chesa Boudin’s “leadership.”

The most enthusiastic supporters of a Boudin-style approach to policing in San Francisco and elsewhere tend to be white college-educated liberals—the mass base, as it were, of the progressive movement. Nonwhite and working-class voters approach the issue of crime quite differently. …

3. Insisting that everyone should look at all issues through the lens of identity politics was a terrible idea and voters hate it. In recent years, huge swathes of the Democratic Party, egged on by progressives, have become infected with an ideology that judges actions or arguments not by their content but rather by the identity of those engaging in them. Those identities in turn are defined by an intersectional web of oppressed and oppressors, of the powerful and powerless, of the dominant and marginalized. With this approach, one judges an action not by whether it’s effective or an argument by whether it’s true but rather by whether the people involved are in the oppressed/powerless/marginalized group or not. If they are, the actions or arguments should be supported; if not, they should be opposed.

This approach is in obvious contradiction to logic and common sense. And it has led much of the Democratic Party to take positions that have little purchase in social or political reality and are offensive to the basic values most Americans hold. Take the vogue for “anti-racist” posturing. This dates back to the mid-teens and gathered overwhelming force in 2020 with the George Floyd police killing and subsequent nationwide protests. It became de rigueur in Democratic circles to solemnly pronounce American society structurally racist and shot through with white supremacy from top to bottom.

Nothing exemplifies this better than the lionization of Ibram X. Kendi, whose thoroughly ridiculous claims were treated as revealed truth by tens of millions of good Democrats, with progressives at the ready to make sure they stuck to the catechism. Kendi wrote, for instance:

There is no such thing as a nonracist or race-neutral policy. Every policy in every institution in every community in every nation is producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity between racial groups…The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination….The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.

Only those who have checked their capacity for critical thinking at the door could possibly take such arguments seriously. But progressives insisted these absurdities must be taken on board. …

4. Telling people fossil fuels are evil and they must stop using them was a terrible idea and voters hate it. Since the days of Barack Obama and an “all of the above” approach to energy production, Democrats, on the urgings of progressives, have embraced quite a radical approach to energy issues. Progressives promulgated the view that climate change is not a dynamic that is gradually advancing, but an imminent crisis that is already upon us and is evident in extreme weather events. It threatens the existence of the planet if immediate, drastic action is not taken. That action must include the immediate replacement of fossil fuels, including natural gas, by renewables, wind and solar, which are cheap and can be introduced right now if sufficient resources are devoted to doing so, and which, unlike nuclear power, are safe. Not only that, the immediate replacement of fossil fuels by renewables will make energy cheaper and provide high wage jobs.

According to the progressive view, people resist rapidly eliminating fossil fuels only because of propaganda from the fossil fuel industry. Any problems with renewables that might be cited, such as their intermittency and unreliability, are being solved. This means that as we use more renewables and cut out fossil fuels, political support for the transition to clean energy should go up because of the benefits to consumers and workers. …

OK: I’d be a little more indulgent on the last of these. The way I see things, if you want to get something done in our system, you have to do it through a toxified, polarising medium of political competition which involves the competition for attention. You dumb it down and moralise the message. You play goodies and baddies. There’s also the success of the right in derailing market based mechanisms. So the left were doing their best to address incredibly important concerns here — and our correspondent didn’t mention that, accompanying the rising rhetoric of crisis was a reasonable evidence base for such rhetoric. Still, I’m not too keen on demonising natural gas just now. I’d leave that for at least another decade or so.

Roughly the way I feel (but would never say)

I had no idea!

The platform formerly known as Twitter swings right: Shock!!

Whodda thunk?

The top political accounts on X have seen their audiences crumble in the months before the election, a signal of the platform’s diminishing influence and usefulness to political discourse under billionaire owner Elon Musk, a Washington Post analysis found.

Politicians on both sides of the aisle have struggled to win the attention they once enjoyed on the platform formerly known as Twitter, according to The Post’s review of months of data for the 100 top-tweeting congressional accounts, including senators, representatives and committees, equal parts Democrat and Republican.

But some of their tweets are still going mega-viral — virtually all of them from Republicans, the analysis shows. The Republicans have also seen huge spikes in follower counts over the Democrats, and their tweets have collectively received billions more views.

X has seen a dramatic exodus of users since Musk took over in 2022, according to independent analysts such as Edison Research, which said in March that X’s usage in the United States had dropped 30 percent since last year. The investment firm Fidelity this month estimated that X’s value has plunged by about 80 percent since Musk’s takeover.

But the viewers that have stayed on X now largely see posts that skew toward the political bent of Musk himself, an avid booster of former president Donald Trump who has jumped onstage with him at rallies, donated $118 million toward his bid for a second term and launched a daily $1 million giveaway for registered voters in swing states. Musk, the world’s richest man, paid $44 billion to buy X and has since become its biggest user, with 200 million followers.

It’s almost impossible to say whether X is explicitly suppressing Democrats, as some liberals have speculated: The Post’s analysis turned up no evidence of direct manipulation. The shift in attention could reflect changing attitudes among users who have stuck around, given that many left-wing users have said they left the platform of their own accord, annoyed by Musk’s antics and X’s redrawn rules.

Lovely essay

How could you not like an essay that begins like this?

I grew up among the professional middle classes in the western suburbs of Chicago during the 1980s. My mother stayed home with me and my brother when we were young, then went to night school to get her CPA before landing a job at a big accounting firm. She disliked it intensely, and finally found the perfect fit as a professor at a community college, where she taught for 35 years.

My dad worked in corporate advertising and also hated it. He once told me that if you win the rat race you are still a rat. He got out, bought a couple of small businesses, and happily sold sandwiches to satisfied customers for the next decade and a half.

Anyway, on with the show:

Oxford is where the children of the masters of the galaxy go to become masters of the universe. I was the Earth-bound state school kid surrounded by the celestial beings of the Ivy League. I was Cameron in a sea of Ferris Buellers. To make it worse, I was brown, and originally from India. I had “striver” written all over me.

I felt so out of place. Who were these Americans who were already chummy with so many people at Oxford? How did they know what drink to order with their salmon?

Somehow, my anxieties got all wrapped up with The New Yorker magazine. … The New Yorker became a symbol of my separateness. Ordering the right drink with salmon, a symbol of my separateness. Having no friends at Oxford, a symbol of my separateness. …

That winter break, I met my dad for a holiday in India. “How’s Oxford?” he asked as we were heading to a restaurant. I unleashed my vocabulary. I was the subaltern in the midst of colonial empire, seeking to speak but always being suffocated by the dominant discourse. I was one of the wretched of the earth, one of the oppressed.

My dad humored me for a few minutes, but finally could not restrain himself from stating the obvious. “If you’re oppressed, what word do you have to describe that boy?”

We were in a chauffeur-driven car in the Colaba neighborhood in south Mumbai, and the kid that my dad was referring to was right outside the window holding two fingers out to me in a gesture of pleading. The other three digits on that hand were stumps where fingers might once have been. And the other hand didn’t exist at all. Another stump. …

What if I was in a conversation with this child? Would I say, “You and me, we’re the same, both victims of an oppressive system”? … Maybe he would turn to me and say, “There is literally nothing I can do to alter my position in this world. But you—you determine your own fate.”

I had told my doctoral advisor I wanted to write a paper on how The New Yorker exemplified a discourse that maintained the colonial power structure and marginalized third world state school students like me. He offered a suggestion: “Instead of making The New Yorker a symbol of separateness, why don’t you read the articles and try discussing the content with your classmates. That’s how you make friends.”

Wise and pragmatic counsel. My advisor had noticed something: with all the fire I spit, all the critical theory I read, all the words I weaponized, I was mostly succeeding in making my own life miserable. I was lonely, and angry, and falling behind. The things I did excel at were of dubious value. I was good at finding everything that was standing in my way. And I could detail the things that everyone else was doing wrong.

But as you grow up, you learn that this path hits a brick wall very quickly.

For example: I stood up after an especially boring session at an interfaith conference and chided the participants for lacking vision and edge and energy. Where are the young people? Where is the heat, the action? My callout achieved the desired result: a string of oohs and aaahhs and mouths agape. But then, something out of the ordinary happened. A woman approached me and said, “You should build that.” …

It took me a long time to shift my paradigm and develop the skill set to turn that idea into reality. I’m glad I did.

I’m not sad that I read those critical theorists. I think it’s a useful perspective to have. My problem is that I deformed the world to fit a narrow worldview, and I let it direct my life. … Critical theory is like a sharp kitchen knife: very useful for some things, like cutting meat, but if you eat your cereal with it, you’ll hurt yourself. And if you point it at someone else, then it’s a weapon.

In some circles, on some campuses, every other utensil has been removed from the intellectual cutlery drawer, replaced with sharp kitchen knives.

There’s a better way. Pluralism means that you cooperate with people of diverse identities, that you learn from the divergent ideologies, that you expand the number of explanatory frameworks you have to make sense of the world. You should not exit college narrower than you entered. And you should not graduate believing that you are less capable than when you began. …

The question before every college student, really, is simple: What will you do with your agency?

Some British humour

John Cleese celebrated his 85th birthday this week

Meanwhile something large just went by …

A welcome voice on the left for Unherd

Bruce Springsteen has more fun than Ta-Nehisi Coates

I’m not reproducing this Unherd column by David Masciotra because I think it’s particularly terrific, but it’s quite interesting until it goes a little off the beam I think.

Memories of 11 September, and the dark days that followed, are universal among geriatric American millennials. As a member of the generation that came of age in the Nineties and early 2000s, I can easily return to those early hours of fear and war, summoning the confluence of mixed emotions — despair, rage, confusion — that accompanied them. But beyond the smoke, and the flames, and the nightmarish pictures of people falling through the sky, my overriding memories of that time can be summarised in two words: Bruce Springsteen.

By the turn of the century, the New Jersey native had already established himself as a rock and roll legend. But his artistic reaction to 9/11 enhanced his importance. Less than a year after the attack, he recorded The Rising, his first album with the E Street Band since the Eighties. Despite the centrality of politics to those frantic days, the collection was strikingly unideological. Instead of protest, Springsteen opted to explore grief and mourning, and how to find hope in the immediate aftermath of a devastating loss.

Among its most effective and moving moments is “Into the Fire”, an overt tribute to the first responders who ascended the stairs of a burning, crumbling building in the desperate hope to save the lives of strangers. “Love and duty called you someplace higher,” Springsteen sings in a tender voice. “Somewhere up the stairs / Into the fire…” The chorus functions as a prayer to the heroic firefighters, police officers, and paramedics: “May your strength give us strength… May your love bring us love…”

In other words, then, Springsteen understood that the rescue workers represented and exercised the best of humanity. They were, and are, worthy of praise and remembrance that transcends narrow political strife. It’s a pride, a heartfelt patriotism, you can still spot today. At a recent rally in Georgia, in support of Kamala Harris, Springsteen emphasised the need for presidential candidates to understand the US, its history, and “what it means to be deeply American”.

Such gentle flag-waving is rare on the progressive Left, placing it at odds with the heavyweights of the Democratic Party. Meanwhile, the Republican Party adores a presidential nominee who recently referred to the United States as a “garbage can”.

This angry new world was arguably forged as far back as 2015. That year, Ta-Nehisi Coates published a memoir, Between the World and Me. Framed as a letter to his teenage son, Coates examined racism in the United States, focusing mainly on police brutality.

Like Springsteen, Coates offered a reaction to 9/11. But this time, the writer is shorn of all sympathy, all grace. “Looking out upon the ruins of America, my heart was cold,” he confesses. Referring to the firefighters and cops, he writes, “They were not human to me. Black, white, or whatever, they were the menaces of nature; they were the fire, the comet, the storm, which could — with no justification — shatter my body.”

It is difficult to find a more contemptible passage in the past two decades of American letters. Yet despite such a chilling lack of empathy, Coates has won nearly every literary prize imaginable, including a National Book Award for Between the World and Me. From the American press, he receives the pious reverence typically reserved for the Pope at Sunday mass.

A rare heretic, Tony Dokoupil of CBS News, recently asked Coates a series of challenging questions about his indifference to Israeli history or suffering. In his latest book, The Message, which has a large section on the Israel-Palestine conflict and attacks Israel as an “apartheid” state, Coates never once mentions October 7. Two intifadas, or indeed any loss of Israeli life, are notable by their absence too. For exercising the mundane obligation of his profession, Dokoupil was reprimanded by the network. Many influential pundits on the progressive Left, notably Mehdi Hasan, screamed about the interview for days on social media. The digital herd stampeded toward Dokoupil’s characterisation of The Message as not out of place in the “backpack of an extremist”. The language is strong, but hardly unfair.

One wonders if to Coates, Israelis, like the firefighters rushing up the stairs of the World Trade Center, aren’t really human. Is that why they are unworthy of inclusion in his one-sided book? Certainly, the contrast with Bruce Springsteen is only heightened when you recall that, on 13 October, he performed a benefit concert for the USC Shoah Foundation, an organisation that preserves the testimony of Holocaust survivors, and raises awareness to the ongoing threat of antisemitism.

As unlikely as it might seem, then, Springsteen and Coates personify a crossroads for the American Left. Liberals and “progressives” can choose a humanistic, big-hearted liberalism, one that seeks common ground in the pursuit of personal freedom and social progress for minority groups. Or they can crawl into a sewer of a narrow delusion, one that pits “oppressors” versus “victims” and “colonisers” against “the colonised” — and where some people, no matter how much they’ve suffered or the grace that they’ve shown despite their suffering, are hardly human at all.

The deification of Coates, and the contempt for the lone journalist who challenged him, is an ill omen. And it’s far from alone. While the American Right has morphed into an autocratic personality cult, assembled around an increasingly deranged Donald Trump, the Left is fighting its own internal battle. So far, the Democratic Party has managed to contain the Leftist revolt against reason to a small number of congressional representatives and city officials. Recently, Cori Bush and Jamaal Bowman lost their seats in Missouri and New York, during Democratic primaries, after mouthing antisemitic bromides against Israel, and articulating extreme positions against law enforcement and the free market.

One still must wonder how long sanity will prevail. To put it differently, it’s possible that American culture no longer has the infrastructure necessary to maintain political movements of humanistic liberalism.

After which the piece gets a little carried away IMO.

HT: Alan Jacobs

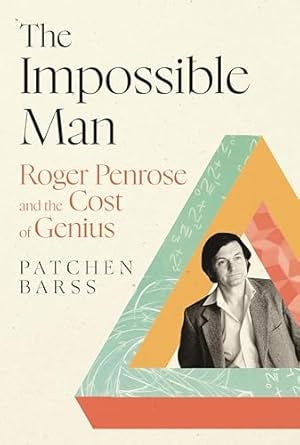

Roger Penrose and pattern recognition

The Oxford professor’s preternatural intuitions about geometry and the universe — especially the nature of black holes — have earned him a 2020 Nobel Prize for physics (and perhaps should have won him a second, for chemistry); a knighthood; and an Order of Merit, perhaps the most exclusive of Britain’s honours, limited to 24 living holders. …

His mathematical legacy includes Penrose diagrams, Penrose tiling (particular ways of fitting geometric shapes together without gaps or overlaps) and Penrose notation, a kind of mathematical shorthand for quantum theory. The man himself, now 93, even took a toilet-roll manufacturer to the cleaners for copying his non-repeating tiling pattern on their quilted offerings (which meant the roll would not bulge inconveniently).

As Toronto-based science journalist Patchen Barss shows in his beautifully composed and revealing biography The Impossible Man, Penrose’s exceptional talent for solving the hidden patterns and puzzles in the universe has long contrasted with his struggle to fit into the world of people. There were stilted bonds with cold parents, fraught love affairs with women and distant relationships with his children.

Penrose confessed to ‘a certain destructive impulse’ — and pursued his academic work at the expense of everything and everyone else

As Barss writes, Penrose’s own pattern of treating every challenge, whether personal or professional, as a problem to be solved “ . . . connected him to ideas so vast and beautiful they swept him away. It also shut out friends and family, leaving them heartbroken over his indifference to their love.” …

A chance visit to an exhibition by MC Escher, the Dutch master of optical illusions, changed his life. “Escher played with perceptions of up and down, foreground and background,” writes Barss, “ . . . as though the artist had reached into Roger’s own mind to pull out these ideas.” Penrose gravitated towards physics, which made full use of his visualisation skills ….

But his personal life was troubled. … Penrose keeps his distance from his three eldest sons, hinting to Barss that contact would detract from work he wants to finish before he dies. For their part, they cannot forgive his behaviour towards their mother Joan. Without contact, Barss observes, Penrose escapes accountability.

Hauntingly, Penrose, who still harbours regrets over Judith, remains angry and upset at his own parents, particularly his non-demonstrative mother. She never had a “sort of warm hugging love about her”, Penrose recalls — seemingly without making the connection to his own children. For all his genius, this impossible man failed to grapple with the most important repeating pattern in his own life.

And gentlemen in England now a-bed shall think themselves accurs'd they were not here…

Frederic Church and his friends in the Hudson School

Our (relative) COVID success

Andrew Podger on our COVID schemozzle.

I started reading the latest offering by economists Steven Hamilton and Richard Holden, Australia’s Pandemic Exceptionalism: How we crushed the curve but lost the race, UNSW Press (henceforth referred to as H&H) on Australia’s COVID-19 experience while I was nursing a deep disappointment that the Albanese government decided not to establish a royal commission into our handling of the pandemic. …

I must now admit that a legally oriented search for wrongdoing by a royal commission might not have given us the clarity that economists Hamilton and Holden have provided in their highly readable account of Australia’s performance. …

There are lessons in particular for the Commonwealth Health Department and Australia’s health establishment: the importance of speed of action in a pandemic, of gathering much more information to monitor the situation and to learn as a pandemic spreads, and of managing risks differently than in non-pandemic circumstances.

It is to be hoped that those free market economic commentators advocating a ‘let it rip’ response, claiming a trade-off between public health and economic objectives, also take heed. The best economic advice was entirely consistent with the best health advice. The two objectives required different but complementary policy measures (the so-called ‘Tinbergen law’ that each policy objective requires its own policy instrument) that needed to be adopted simultaneously and consistently.

There are lessons also about the capacity of the administrative state that too often is undervalued: the capacity to implement the measures needed in the timeframe such an emergency demands.

The big picture story told by H&H is of Australia’s overall success:

Seventy-one deaths per million by the end of 2021 were amongst the lowest across the OECD (there were 2,202 in the US, 2,492 in the UK and 1,425 in Sweden [the ‘let-it-rip’ model]).

Australia’s daily new confirmed cases per million were a tiny fraction of those in most other countries throughout 2020.

Australia’s GDP fell by just 0.3% in 2020 and grew by 2.1% in 2021 and 4.3% in 2022 (US GDP fell by nearly 10%, the UK’s by over 20% and Sweden’s by about 8%).

Our employment-to-population ratio dipped from just over 62% to 58% in early 2020 but returned to 62% in 2021 and has since grown to over 64% (in the US the ratio fell from around 61% to under 52% and has never fully recovered, being around 60% in 2024, a full 4 percentage points below Australia’s).

Australia’s overall performance has only been matched by a small number of countries, including New Zealand and South Korea.

The economic success was particularly remarkable. The reasonably early (and essential) closure of our international border followed by movement restrictions kept us close to a COVID-free environment. But these measures necessitated a huge fiscal response. Treasury had learned from the 2008 GFC both what to do when faced with such a huge shock to the economy and the need to do some things differently given the different nature of this shock. It was important to ‘go early, go big’ (to quote two of Ken Henry’s famous three GFC response priorities), but this time not to focus so much on ‘go households’ (Henry’s third priority in 2008) but to look for measures that would preserve employee/employer connections.

The aim was to achieve a V-curve recovery, compensating employers immediately for the government closures and also facilitating rapid recovery as soon as those closures could safely be lifted, i.e., when the population was sufficiently vaccinated and employees could return to work.

Critical to the success was not just the quality of the economic advice provided but also the acceptance of that advice by a conservative government, setting aside any ideological unease (despite urging from some external advisers). H&H are particularly fulsome in their praise of then-treasurer Josh Frydenberg and the informal support he received from former prime minister John Howard.

A third critical factor was the quality of some of our administrators, particularly in the ATO and ABS, and the capacity of the administrative state they had nurtured (as the ‘stewards’ of that state capacity, to use the sometimes-vacuous term in a meaningful way). H&H refer to the ‘hero’ of our economic response, not a person but the ‘single touch payroll’ system developed by the ATO over the previous decade to make tax collection much easier for both the ATO and businesses by plugging directly into businesses’ systems. It was this system that allowed the ATO to advise the government confidently of its capacity to implement — very quickly — the ‘Jobseeker’ program which Treasury saw as the most effective stimulus measure to use in a pandemic — paying businesses to pay their employees even when the employees could no longer work.

The ABS also drew on its recent investments into utilising business administrative data to develop new statistical collections that could inform Treasury and government ministers far more quickly than it could have in the past about the impact of closures and other developments in response to the pandemic.

H&H are careful to avoid relying on hindsight. They mention some commentators’ criticism of the scale of the economic response and the failure to require repayment where the assistance proved unnecessary. In rejecting such criticism, H&H highlight the importance of speed at the time and of gaining widespread business support for the Jobseeker initiative in particular. Some overspend was far more acceptable than the risk of long-term scarring as is now evident in the US.

The economic successes would have been even more impressive but for inexplicable failures by the Commonwealth Health Department and the health establishment later in 2020 and 2021. H&H are scathing about the apparent disconnect between the economic advice and this later public health advice. The economic advice was all about doing whatever it takes to avoid a recession, providing all the fiscal protection needed as quickly as possible and in a way that would facilitate rapid recovery as soon as the population was safe, i.e., as soon as sufficient vaccination cover was reached. Health’s job was not just to ‘crush the curve’ to limit the spread of the disease, but to do all it could, as quickly as it could, to achieve adequate vaccination coverage. That did not happen.

Australia’s vaccination rate was only 6% in mid-2021 when the average across the OECD was 32%. For two months, Australia’s performance was dead last amongst the OECD. It took until October 2021 for Australia to catch up to the then-average of around 60%.

Instead of an insurance approach, spreading bets across all possible vaccine solutions in 2020, the Health Department invested in just two, one of which proved unsuccessful and the other of limited success. Was it narrowminded nationalism (to bet on the Queensland possibility or CSL’s manufacturing opportunity), or a penny-pinching mindset? Either way, the attention was not on the central objective of achieving sufficient coverage from an effective vaccine as soon as possible. Despite assurances from the chief medical officer (and later departmental secretary) — repeated by the health minister and the prime minister — that it was ‘not a race’, it was and always had been. …

The short-sighted approach to purchasing the vaccines and, later, to approving vaccines and delivering vaccinations, was repeated by the health authorities in their delayed and limited use of COVID testing before the vaccines became available. Testing large numbers of people was one of the most important public health tools then available. It would allow for better targeted stay-at-home orders as opposed to requiring everyone to isolate, and it would give the community much greater confidence that they were unlikely to come into contact with a COVID-positive person.

But Australia did not pursue mass testing for way too long. It focused the testing on ‘hotspots’, and responded only to symptomatic cases rather than asymptomatic cases as well. Simple mathematics should have told the authorities that this would not assist in curbing the spread of the disease. Then the authorities focused on the ‘gold standard’ PCR testing that took days to yield results, delaying approval of the far faster (and cheaper) RATs a full six months after the FDA gave approval in the US, taking many more months before large numbers of RATs were purchased and distributed. The cost of these delays was in terms of excessively wide and lengthy lockdowns including children’s long absence from schooling.

As H&H make clear, these criticisms are not just from hindsight. … They now estimate the cost of the failures as at least $30 billion (and probably over $50 billion) plus loss of life, lost education of a cohort of children and the mental health impact and misery for many suffering lockdowns that might have been avoided.

Having fun, being silly and getting paid for it by calling it art

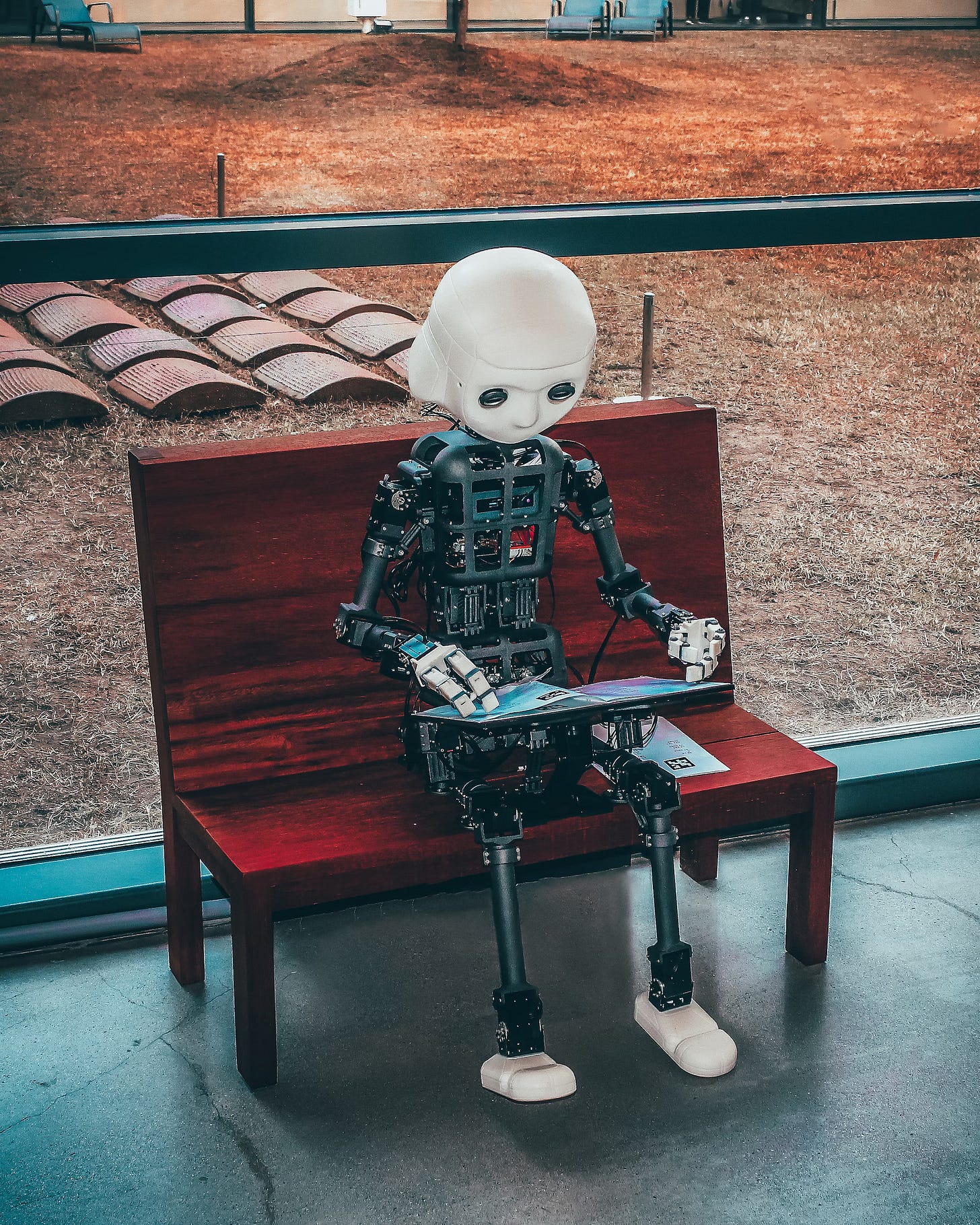

Computers don’t write, play or even compute. SHOCK!! Top notch philosopher

I’ve encountered Alva Noë when I was studying embodied cognition which I wrote up in this essay. I loved the way in which the field brought the practicality of robotics to demonstrating what had previously been a philosophical topic — what was wrong with Descartes way of framing the relationship of mind to matter.

Noë has now turned his mind to AI — as you do. Indeed, he’s more bracing because of the simple conviction he brings and argues for, to the question of whether AI can think, act or even calculate. Hint: no.

So thanks to reader Robert Banks who drew my attention to this piece of his.

Computers don’t actually do anything. They don’t write, or play; they don’t even compute. Which doesn’t mean we can’t play with computers, or use them to invent, or make, or problem-solve. The new AI is unexpectedly reshaping ways of working and making, in the arts and sciences, in industry, and in warfare. We need to come to terms with the transformative promise and dangers of this new tech. But it ought to be possible to do so without succumbing to bogus claims about machine minds. …

[S]ome scientists … take for granted what can only be described as a wildly simplistic picture of human and animal cognitive life. … The surreptitious substitution (to use a phrase of Edmund Husserl’s) of this thin gruel version of the mind at work – a substitution that I hope to convince you traces back to Alan Turing and the very origins of AI – is the decisive move in the conjuring trick. …

Everywhere in Turing’s work, the focus is on imitation, replacement and substitution. Consider his contribution to mathematics. A Turing machine is a formal model of the informal idea of computation: ie, the idea that some problems can be solved ‘mechanically’ by following a recipe or algorithm. (Think long division.) Turing proposed that we replace the familiar notion with his more precise analogue. Whether a given function is Turing-computable is a mathematical question, one that Turing supplied the formal means to answer rigorously. But whether Turing-computability serves to capture the essence of computation as we understand this intuitively, and whether therefore it’s a good idea to make the replacement, these are not questions that mathematics can decide. Indeed, presumably because they are themselves ‘too meaningless to deserve discussion,’ Turing left them to the philosophers. …

Instead of arguing about what thinking is, Turing envisions a scenario in which machines might be able to enter into and participate in meaningful human exchange. Would their ability to do this establish that they can think, or feel, that they have minds as we have minds? These are precisely the wrong questions to ask, according to Turing. What he does say is that machines will get better at the game, and he went so far as to venture a prediction: that by end of the century – he was writing in 1950 – ‘general educated opinion will have altered so much that one will be able to speak of machines thinking without expecting to be contradicted.’ …

None of us has ever found out or proved that the people around us in our lives actually think or feel. We just take it for granted. And it is this observation that motivates his conception of his own task: not that of proving that machines can think; but rather that of integrating them into our lives so that the question, in effect, goes away, or answers itself.

It turns out, however, that not all of Turing’s replacements and substitutions are quite so straightforward as they seem. Some of them are downright misleading.

Consider, first, Turing’s matter-of-fact suggestion that we replace talking by the use of typed messages. He suggests that this is to make the game challenging. But the substitution of text for speech has an entirely different effect: to lend a modicum of plausibility to the otherwise absurd suggestion that machines might participate at all.

Speech is active, felt and improvisational. It has more in common with dancing than text-messaging. We are so much at home, nowadays, under the regime of the keyboard that we don’t even notice the ways text conceals the bodily reality of language.

Although speech is not formally specifiable, text – in the sense of text-messaging – is. So text can serve as a computationally tractable proxy for real human exchange. By filtering all communication between the players through the keyboard, in the name of making the game harder, Turing actually – and really this is a sleight of hand – sweeps what the philosopher Ned Block has called the problem of inputs and outputs under the rug.

But the substitution of text-message for speech is not the only sleight of hand at work in Turing’s argument. The other is introduced even more surreptitiously. This is the tacit substitution of games for meaningful human exchange. Indeed, the gamification of life is one of Turing’s most secure, and most troubling, legacies.

The problem is that Turing takes for granted a partial and distorted understanding of what games are. From the computational perspective, games are – indeed, to be formally tractable, they must be – crystalline structures of intelligibility, virtual worlds, where rules constrain what you can do, and where unproblematic values (points, goals, the score), and settled criteria of success and failure (winning and losing), are clearly specified.

But clarity, regimentation and transparency give us only one aspect of what a game is. Somehow Turing and his successors tend to forget that games are also contests; they are proving grounds, and it is we who are tested and we whose limitations are exposed, or whose powers as well as frailties are put on display on the kickball field, or the four square court. A child who plays competitive chess might suffer from anxiety so extreme they are nauseated. This visceral expression is no accidental epiphenomenon, an external of no essential value to the game. No, games without vomit – or at least that live possibility – would not be recognisable as human games at all. …

Here’s the critical upshot: human beings are not merely doers (eg, games players) whose actions, at least when successful, conform to rules or norms. We are doers whose activity is always (at least potentially) the site of conflict. Second-order acts of reflection and criticism belong to the first-order performance itself. These are entangled, and with the consequence that you can never factor out, from the pure exercise of the activity itself, all the ways in which the activity challenges, retards, impedes and confounds. To play piano, for example – that other keyboard technology – is to fight with the machine, to battle against it.

Let me explain: the piano is the construction and elaboration of a particular musical culture and its values. It installs a conception of what is musically legible, intelligible, permitted and possible. A contraption made of approximately 12,000 pieces of wood, steel, felt and wire, the piano is a quasi-digital system, in which tones are the work of keystrokes, and in which intervals, scales and harmonic possibilities are controlled by the machine’s design and manufacture.

The piano was invented, to be sure, but not by you or me. We encounter it. It pre-exists us and solicits our submission. To learn to play is to be altered, made to adapt one’s posture, hands, fingers, legs and feet to the piano’s mechanical requirements. Under the regime of the piano keyboard, it is demanded that we ourselves become player pianos, that is to say, extensions of the machine itself.

But we can’t. And we won’t. To learn to play, to take on the machine, for us, is to struggle. It is hard to master the instrument’s demands.

To master the piano is not just to conform to the machine’s demands. It is to push back, to say no

And this fact – the difficulty we encounter in the face of the keyboard’s insistence – is productive. We make art out of it. It stops us being player pianos, but it is exactly what is required if we are to become piano players.

For it is the player’s fraught relation to the machine, and to the history and tradition that the machine imposes, that supplies the raw material of musical invention. Music and play happen in that entanglement. To master the piano, as only a person can, is not just to conform to the machine’s demands. It is, rather, to push back, to say no, to rage against the machine. And so, for example, we slap and bang and shout out. In this way, the piano becomes not merely a vehicle of habit and control – a mechanism – but rather an opportunity for action and expression.

And, as with the piano, so with the whole of human cultural life. We live in the entanglement between government and resistance. We fight back.

Consider language. We don’t just talk, as it were, following the rules blindly. Talking is an issue for us, and the rules, such as they are, are up for grabs and in dispute. We always, inevitably, and from the beginning, are made to cope with how hard talking is, how liable we are to misunderstand each other, although most of the time this is undertaken matter-of-factly and without undue stress.

As if speaking were the straightforward application of rules, or playing the piano was just a matter of doing what the manual instructs. But to imagine language users who were not also actively struggling with the problems of talk would be to imagine something that is, at most, the shell or semblance of human life with language. It would, in fact, be to imagine the language of machines (such as LLMs).

John Kay on the 21st century corporation

John Kay is a terrific writer and terrific economist. He knows his economic theory, but he’s more in the tradition of Adam Smith, someone who looks at business as an honourable estate unless and until those practicing it do dishonourable things. And those practicing it have been doing dishonourable things. And systematising dishonour in various ways.

I’ve only just started reading the book (listening mostly) but am enjoying it immensely and finding it very stimulating, not so much about economics, but about the deeper things that are being sacrificed on the altar of neoliberal instrumentalism.

Introduction: Business and society.

And no one puts new wine into old wineskins; or else the new wine bursts the wineskins, the wine is spilled, and the wineskins are ruined. But new wine must be put into new wineskins.

Mark 2:22, New King James Version1

In 1901 financier J. P. Morgan orchestrated the creation of US Steel, then by almost any measure the largest company in the world. Two years earlier, John D. Rockefeller had consolidated his activities into Standard Oil of New Jersey, which controlled around 90 per cent of refined oil products in the United States. Steel and oil were essential elements in the rise of the automobile industry, which would transform both everyday life and the ways in which people thought about business.

Business historian Alfred Chandler documented the rise of the modern managerial corporation in his magisterial Strategy and Structure (1962).2 The book showcased General Motors, along with chemical giant DuPont, retailer Sears Roebuck and Standard Oil of New Jersey. These companies dominated their industries in the United States and increasingly operated internationally. They exerted political influence, and their turnover exceeded the national product of many states. Their combination of economic and political power seemed to secure their dominance in perpetuity.

It didn’t. In 2009 General Motors (GM) entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy. GM is still – just – the top-selling US automobile supplier, but its global production lags far behind that of Toyota and Volkswagen. DuPont has broken itself up, and Sears Roebuck is more or less defunct. These failures are not because people have ceased to drive cars and shop or because business no longer requires chemical products. Incumbents lost out because other businesses met customer needs more effectively. Among Chandler’s examples only Standard Oil of New Jersey – now ExxonMobil – continues to enjoy its former leadership status. Somewhat quixotically, in view of the widespread demand for a transition from fossil fuels.

In the 1970s you might presciently have anticipated that information technology would be key to the development of twenty-first-century business. And many savvy investors did; their enthusiasm made IBM the world’s most valuable corporation. The leading computer company of the age would surely lead the race to the new frontier. That wasn’t how it worked out.

On Wall Street they called the upstarts ‘the FAANGs’ – Face-book (Meta), Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google (Alphabet). Then the fickle fashion of finance favoured the ‘Magnificent Seven’, with Netflix replaced by Nvidia, and Tesla and Microsoft added to the list – the latter restored to fortune after missing out on the Apple-led shift to mobile computing in the first decade of the new century. Microsoft is actually the longest established of these titans of the modern economy, famously founded in 1975 by Harvard dropouts Paul Allen and Bill Gates. Four of these businesses companies began trading only in the twenty-first century. None of the FAANGs is a manufacturer (I will explain Apple later.) The employees of these companies are not the labouring poor, victims of class oppression; many hold degrees from prestigious universities. (I will come back to Amazon later.) The workers are the means of production.

In 2023 investors believed that the ‘Magnificent Seven’ represented the future of business. They clamoured to buy their stock, as they had once clamoured to buy US Steel, General Motors and IBM. And these investors are likely to be right – for a time. But experience suggests the dominance of the seven is likely to be as transitory as that of the large businesses of earlier generations. As I write this, negotiations are proceeding for the rump of US Steel to be bought by Nippon Steel of Japan, and Andrew Carnegie and the Gilded Age have become a footnote to history. Thus the mighty fall – or just slowly fade away.

A central thesis of this book is that business has evolved but that the language that is widely used to describe business has not. The world economy is not controlled by a few multinational corporations; such corporations have mostly failed even to control their own industries for long. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries capital was required to build, first, textile mills and iron works, then railways and steel mills and subsequently automobile assembly lines and petrochemical plants. These ‘means of production’ were industry-specific – there is not much you can do with a railway except run trains along it, and if you want to be an engine driver you need to seek employment with a business that operates (but, as I will explain, does not necessarily own) a track and a train.

The leading companies of the twenty-first century have little need of such equipment. The relatively modest amounts of capital they raise are used to cover the operating losses of a start-up business. The physical assets required by twenty-first-century corporations are mostly fungible: they are offices, shops, vehicles and data centres which can be used in many alternative activities. These ‘means of production’ need not be owned by the business that uses them and now mostly they are not.

Thus the owners of tangible capital, such as real estate companies and vehicle lessors, no longer derive control of business from that ownership. Labour is no longer subjected to the whims of capitalist owners of the means of production. Often workers do not know who the owners of the physical means of production are, or who the shareholders of the business they work for are, and they don’t know because it doesn’t matter. They work for an organisation that has a formal management structure but whose hierarchy is relatively flat and participative.

Necessarily so. In modern businesses the ‘boss’ can’t issue peremptory instructions to subordinates, as Andrew Carnegie and Henry Ford did, because modern bosses don’t know what these instructions should be: they need the information, the commitment and, above all, the capabilities which are widely distributed across the organisation. The modern business environment is characterised by radical uncertainty. It can be navigated only by assembling the collective knowledge of many individuals and by developing collective intelligence – a problem-solving capability which distinguishes the firm from its competitors, and even its own past. Relationships in these businesses cannot be purely transactional: they require groups of people working together towards shared objectives, and such cooperative activity necessarily has a social as well as a commercial dimension.

Collective knowledge is the accumulation of the facts and theories we can find in libraries and on Wikipedia, augmented by insights from our own experience and that of others. Other animals mostly know what they have learned for themselves. We understand science and appreciate art because of the endeavours of great scientists and famous artists and the efforts of our teachers to explain their achievements to us. Collective knowledge also includes what we have learned about ourselves and each other through our social and business interactions. When to praise and when to criticise, when to follow and when to lead. Collective knowledge is sometimes described as ‘the wisdom of crowds’, but the wisdom of crowds lies in the aggregate of knowledge rather than the average of knowledge. No one knows everything about anything or much about everything.

The twenty-first-century corporation is defined by these human capabilities, not its physical capital. The successful firm builds distinctive capabilities and distinctive collections and combinations of capabilities – capabilities such as supplier or customer relationships, technical and business process innovations, brands, reputations and user networks. These things can only be – at most – approximately replicated by competitors. Such differentiation among firms means that the structure of modern industry is very different from that of the past, which featured an economy in which essentially similar farms, mills and steelworks competed in the production of essentially similar products in capital-intensive and purpose-specific facilities.

As a result, what we call ‘profit’ is no longer primarily a return on capital but is ‘economic rent’. The term ‘economic rent’ came into use in what was still a predominantly agricultural economy to describe the return that accrues to landowners because some lands are more fertile or better located than others. Today economic rent is used to describe the earnings that arise because some people, places and institutions have commercially valuable talents which others struggle to emulate. Economic rent accrues to silver-tongued attorneys, brilliant brain surgeons, dashing dealmakers and to sports and film stars. Economic rent is earned by Taylor Swift, and by businesses and house owners in Silicon Valley; economic rent is derived from the unique attractions of Venice and the enthusiasm of world-wide supporters of Manchester United.

But economic rent also describes and explains the revenue that is generated because some firms are better than others at providing the goods and services that their customers want. The economic rent earned by Apple and Amazon, like the economic rent accruing to Swift and Manchester United and arising in Silicon Valley and Venice, is the result of doing things better than other people, places and organisations. All these people, places and organisations have monopolies – of being their impressively differentiated selves. The traditional association of economic rent with monopoly is thus true, but trivial.

And we should welcome that differentiation and its associated ‘monopolies’. The perfectly competitive market in which every product is homogeneous and every producer is equally efficient is not an ideal but a stationary equilibrium in which enterprise and innovation are absent. The purpose of economic organisation is to create combinations of factors of production that yield more value than the same factors would in alternative uses. And to do so successfully is to create a source of economic rent.

But when the term ‘economic rent’ is mentioned in modern texts on economics, business and politics, it is most often in the context of ‘rent-seeking’: the attempt by individuals and companies to appropriate some of the value created by other individuals and companies, by establishing monopolies or providing unneeded intermediary services. Such rent-seeking is indeed a major blight on modern economies, and a better appreciation of the nature and origins of economic rent will better equip us to tackle it. We need to rein in the excesses of financial intermediation. We need to limit the use of political influence to gain favoured positions; to win contracts, to establish monopolies, to secure incumbent-friendly regulations. It is not the purpose of this book to propose remedies for rent-seeking: the implications of my analysis for business and public policy, both of which should promote the rents that arise from innovative differentiation and eliminate the ones that are the result of the abuse of political institutions, will be the task of a successor volume. My objective here is to promote what I regard as an essential preliminary: a better understanding of how business works, and an explanation of how it does not work in the ways many people – both critics and apologists – think.

An understanding of the concept, origins and effects of economic rent is essential to understanding not only the financial accounts of firms but also the distribution of income and wealth in the modern economy. But the inherited terminology of capital and capitalism gets in the way of that understanding. Even sophisticated investors examine ‘return on capital employed’ (ROCE), although the return often has no more connection to the capital employed than it has to the amount of water used (ROW) or the number of meetings held (ROM).

Economic rent is not an anomaly but a central and valuable feature of a vibrant economy. Economic advance occurs when people and businesses create rents by doing things better, and it progresses further by inspiring others to try to compete them away. If this is capitalism, then I am a supporter of capitalism. But the process I describe has very little to do with ‘capital’ and nothing whatsoever to do with any struggle between capitalists and workers for control of the means of production. The economic system I favour and the one described in this book is better described as a market economy, or better still a pluralist economy, than as a capitalist economy. A pluralist economy is one in which people are free to do new things (and often fail at them) without requiring the approval of some central authority. A pluralist economy is a system in which consumers are able to make their wants known in a competitive environment that rewards success in meeting those wants.

But the pluralism of a market economy also requires a discipline in which failure is acknowledged and leads to change. Bureaucratic organisations find such self-awareness hard. IBM, General Motors and US Steel failed economically for more or less the same reasons that the Soviet Union failed economically: the difficulty centralised authorities encounter in adapting to changing technologies and changing needs. These institutions were slow to move and slow to acknowledge failure. However, the economic underperformance of IBM, GM and US Steel led only to the decline of these companies. Microsoft and Apple, Toyota and Tesla, Nucor and Arcelor Mittal were able to take their place. But the economic underperformance of the Soviet Union led to the decline, and ultimately demise, of an entire political system.

The term ‘capitalism’ came into being to describe an economy designed and controlled by a bourgeois elite. Both supporters and critics of modern business frequently conflate this historic caricature of ‘capitalism’ with today’s reality of a market or pluralist economy, whose essential characteristic is that it is not controlled, or not controlled for long, by anyone at all. The mismatch of language and reality extends further. In the second half of the twentieth century, business evolved from an industrial structure characterised by large-scale production facilities staffed by low-skilled workers to one populated by knowledge workers sharing their collective intelligence in a cooperative environment. But the dominant narrative of how the business world did and should work evolved in the opposite direction. Economic relations were defined in purely transactional terms; intrinsic motivation and professional ethics were replaced by targets and bonuses. The purpose of business, MBA students were told, was not to meet the needs of customers and society but to create ‘shareholder value’ for anonymous stockholders.

The further, but closely related, paradox is that as capital became less central to the operation of business, the financial sector expanded greatly in size and remuneration. And the degraded values of parts of the financial sector spread to business. Both business founders and senior executives rewarded themselves handsomely for their profession of devotion to the cause of shareholder value. As a result of the erosion of business ethics and the evidence of indefensible inequalities, the twenty-first-century corporation faces a crisis of legitimacy. Today the public hates the producers even as it laps up the products. And, as I shall describe all too graphically, the managerial proponents of shareholder value often ended up destroying not only shareholder value but also the very businesses that their abler and better-motivated predecessors had created.

Both the intellectual origins and the practical application of these approaches, promoting individualism and emphasising shareholder value, come from the United States. But the influence of these ideas has been global. Business operates internationally, but all businesses are subject to the laws, regulations, customs and societal expectations both of the country in which they are registered or incorporated and of the countries in which they operate. It should hardly be necessary to say that these laws, regulations, customs and societal expectations differ from country to country. But it is necessary to say that they differ, because so much of what is written about business fails to recognise that both the legal duties and the expected behaviour of company directors and executives depend on where the company is based and where it is doing business. The relevant differences are not just those between the US and Russia, or Canada and Japan, but also between Delaware and California and – I shall give these countries specific attention – between Britain, Germany and the United States. And the differences and similarities between these jurisdictions and those of Asian societies are likely to be crucial to the development of the twenty-first-century corporation.

This is a book written by a British economist, and I offer no apology for the fact that much of my own business experience and knowledge is derived from the UK. Britain had a central role in the emergence of modern finance, modern law and modern institutions, and engaged in a colonial project that spread these developments around the world. The Industrial Revolution began in the UK, and the most influential business texts of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and Karl Marx’s Capital – were written close to my boyhood home in Edinburgh and my current office in London respectively. Economics was the foundational discipline for an understanding of business for both Smith and Marx – although, as I will explain, modern economics has contributed less to an understanding of modern business than might reasonably have been hoped.

Still, if one were to seek twentieth-century works of similar significance, one would have to look to the United States. Perhaps to Chandler’s Strategy and Structure, noted above, or to The Modern Corporation and Private Property, in which Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means first documented the transition in American business from the robber barons of the Gilded Age to the managerially controlled businesses of the twentieth century.3

If any individual exemplified that transition it was Alfred Sloan, the General Motors executive who was perhaps the greatest businessman of the twentieth century. As Sloan and his Chief Financial Officer, Donaldson Brown, approached retirement, they were anxious to ensure that the lessons that they had learned would be preserved for subsequent generations. Brown hired Peter Drucker, one of the numerous Viennese intellectuals who had fled the increasingly Nazified Europe for the United States, to tell the story.

The result was a business classic, Concept of the Corporation, which made Drucker the first management ‘guru’.4 Sloan and his colleagues did not like the book, and publishers were sceptical that a book about business would sell. How wrong could they have been! Seventy-five years later Concept of the Corporation is still in print.

And every bookshop now has a section devoted to business books. Mostly, they fall into one of two categories. One type has titles such as ‘Flexagility™ – the Secret of Delighting Customers and Raking in Enormous Profits’. You will find them in airport bookstalls, not far from the self-help manuals. Their authors make a living, often a rewarding one, from consultancy or the delivery of ‘motivational speeches’. The contents of these volumes are unlikely to engage your attention through even the shortest flight. Another genre comprises books with titles like ‘Fleeced, Poisoned and Spied Upon – How Capitalism is Fuelling Inequality, Damaging our Well-Being and Destroying the Planet.’ These are written for people who welcome confirmation of what they think they already know.

This book fits neither of these categories. I hope that thoughtful executives – and there are many – will find something of interest in it, but I do not set out to offer tips for ambitious young managers. My target audience is people who would never normally pick up a business book – people who read popular science or history, but might welcome an intellectually serious, even sometimes challenging, approach to a subject with whose detail they are unfamiliar. I hope this book might stimulate students and young people who might be thinking of a business career or would just like to learn more about business. I would like to think they might read it and even enjoy it – and perhaps conclude that a career in business has more to offer than just financial reward.

I am probably going to have to buy that John Kay book. I loved Obliquity and Other People’s Money.

I feel obligated to mention this: https://tempo.substack.com/p/new-training-course-by-darktriad