Crimes of the modern era: sorting them out

And other things I've seen this week

The big beautiful death toll

One million deaths from USAID cuts

From Tim Harford, the Undercover Economist. He isn’t up to Hitler, Stalin and Mao’s record of deaths, but he’s getting into the league of Pol Pot whose reign produced over 1.5 million dead.

One death is a tragedy. A million deaths is just a statistic. If Stalin ever said such a thing, he wasn't the first — but the ghoulish claim has stuck to him because he is one of very few politicians with more than a million deaths on his conscience.

The list of government actions that deliberately or negligently led to the deaths of more than a million people is short and ugly. There are civil wars, famines and a cluster of atrocities surrounding the second world war, but not many governments have been so evil or so reckless as to pass that horrendous target.

Incredibly, there is now a case for adding the Trump administration to the list. Elon Musk boasted in early February that, "We spent the weekend feeding USAID into the wood chipper." The White House budget request for next year pencils in a cut of two-thirds to global health and humanitarian funding... that cut would plausibly cause a million deaths in the next 12 months alone...

Despite the caveats, a million deaths is a staggering number. It comes from Charles Kenny and Justin Sandefur, two respected researchers at the think-tank the Center for Global Development. They reckon that if the cuts to humanitarian assistance happen — from $8.8bn to $2.5bn — then 675,000 people are likely to die from HIV within a year, and 285,000 from malaria or tuberculosis...

Pepfar (the President's Emergency Plan for Aids Relief, established by George W Bush) supplies antiretroviral drugs that keep 20 million people alive. The effectiveness of these drugs is well understood. They suppress the virus and prevent transmission, including from mother to baby...

The US secretary of state Marco Rubio has maintained that life-saving aid is continuing, but clinics have closed, and people are finding it impossible to get the medication they need to keep them alive...

Few people in the foreign aid industry would argue every cent saves lives... In some cases it might be desirable for national governments to find their own funding... Yet this is no way to reform anything. The cuts are so abrupt that life-saving services are falling apart before our eyes.

A few former USAID staffers have been working to salvage something from the wreckage... "We originally called ourselves the Lifeboat Project," says Robert Rosenbaum of PRO. "And I think that metaphor holds better than any other."

The darkness is justified. When a huge ship sinks, lifeboats can save lives, but you need enough lifeboats, and you need enough time. We have neither...

A million deaths may be a statistic, but it is also a million tragedies. Most of these tragedies could still be prevented.

War as entertainment (from 2008)

Deep fakes

Turns out it’s harder to stop deep fakers who pay your bills

Move fast and don’t fix things - if they’re making you money that is. A creepy business.

And just before the main article, don’t forget Facebook’s move fast and don’t fix things approach to atrocities against the Rohingya. As Amnesty found:

Facebook … was made aware of its role in contributing to the atrocities against the Rohingya ethnic group years before 2017, and it both failed to heed such warnings at the time and took “wholly inadequate” measures to address issues after the fact.

And here’s Martin Wolf.

I have an alter ego or, as it is now known on the internet, an avatar. My avatar looks like me and sounds at least a bit like me. He pops up constantly on Facebook and Instagram. Colleagues who understand social media far better than I do have tried to kill this avatar. But so far at least they have failed.

Why are we so determined to terminate this plausible-seeming version of myself? Because he is a fraud — a "deepfake". Worse, he is also literally a fraud: he tries to get people to join an investment group that I am allegedly leading. Somebody has designed him to cheat people, by exploiting new technology, my name and reputation and that of the FT. He must die. But can we get him killed?

I was first introduced to my avatar on March 11 2025. A former colleague brought his existence to my attention and I brought him at once to that of experts at the FT...

My expert colleague contacted Meta and after a little "to-ing and fro-ing", managed to get the offending adverts taken down. Alas, that was far from the end of the affair. In subsequent weeks a number of other people, some whom I knew personally and others who knew who I am, brought further posts to my attention. On each occasion, after being notified, Meta told us that it had been taken down. Furthermore, I have also recently been enrolled in a new Meta system that uses facial recognition technology to identify and remove such scams.

In all, we felt that we were getting on top of this evil. Yes, it had been a bit like "whack-a-mole", but the number of molehills we were seeing seemed to be low and falling. This has since turned out to be wrong. After examining the relevant data, another expert colleague recently told me there were at least three different deepfake videos and multiple Photoshopped images running over 1,700 advertisements with slight variations across Facebook, and Instagram. The data, from Meta's Ad Library, shows the ads reached over 970,000 users in the EU alone — where regulations require tech platforms to report such figures...

These ads were purchased by ten fake accounts, with new ones appearing after some were banned. This is like fighting the Hydra!

That is not all. There is a painful difference, I find, between knowing that social media platforms are being used to defraud people and being made an unwitting part of such a scam myself. This has been quite a shock. So how, I wonder, is it possible that a company like Meta with its huge resources, including artificial intelligence tools, cannot identify and take down such frauds automatically, particularly when informed of their existence?...

A spokesperson for Meta itself said: "It's against our policies to impersonate public figures and we have removed and disabled the ads, accounts, and pages that were shared with us."

Meta said in self-exculpation that "scammers are relentless and continuously evolve their tactics to try to evade detection, which is why we're constantly developing new ways to make it harder for scammers to deceive others — including using facial recognition technology." Yet I find it hard to believe that Meta, with its vast resources, could not do better. It should simply not be disseminating such frauds.

In the meantime, beware. I never offer investment advice. If you see such an advertisement, it is a scam...

Above all, this sort of fraud has to stop. If Meta cannot do it, who will?

Eric Hoel on Walmart

Inveterate Substacker Eric Hoel explains his latest project thus:

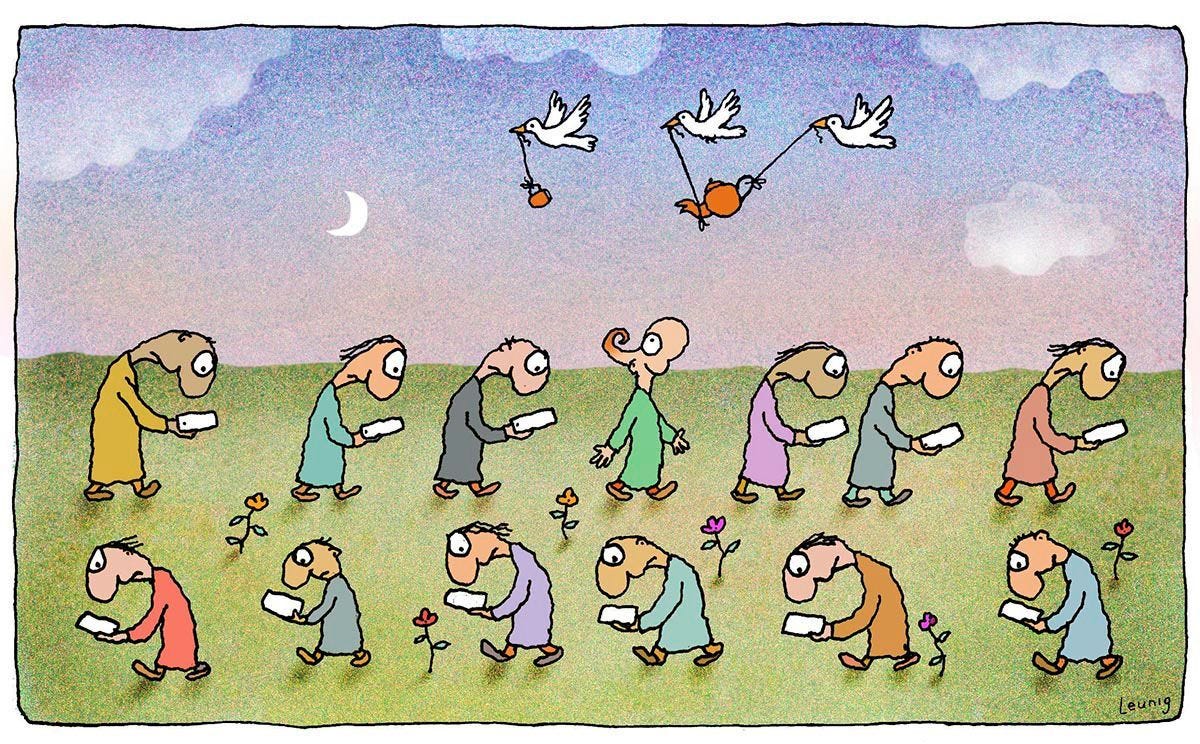

When you become a new parent, you must re-explain the world, and therefore see it afresh yourself.

A child starts with only ancestral memories of archetypes: mother, air, warmth, danger. But none of the specifics. For them, life is like beginning to read some grand fantasy trilogy, one filled with lore and histories and intricate maps.

Yet the lore of our world is far grander, because everything here is real. Stars are real. Money is real. Brazil is real. And it is a parent’s job to tell the lore of this world, and help the child fill up their codex of reality one entry at a time.

Below are a few of the thousands of entries they must make.

Other entries can be found in Part 1. This is Part 2 of a serialized book I’m publishing here on Substack. It can be read in any order. Further parts will crop up semi-regularly.

Here’s a sample entry. His other two on this post are cicadas and stubbornness.

Walmart

Walmart was, growing up, where I didn’t want to be. Whatever life had in store for me, I wanted it to be the opposite of Walmart. Let’s not dissemble: Walmart is, canonically, “lower class.” And so I saw, in Walmart, one possible future for myself. I wanted desperately to not be lower class, to not have to attend boring public school, to get out of my small town. My nightmare was ending up working at a place like Walmart (my father ended up at a similar big-box store). It seemed to me, at least back then, that all of human misery was compressed in that store; not just in the crassness of its capitalistic machinations, but in the very people who shop there. Inevitably, among the aisles some figure would be hunched over in horrific ailment, and I, playing the role of a young Siddhartha seeing the sick and dying for the first time, would recoil and flee to the parking lot in a wave of overwhelming pity. But it was a self-righteous pity, in the end. A pity almost cruel. I would leave Walmart wondering: Why is everyone living their lives half-awake? Why am I the only one who wants something more? Who sees suffering clearly?

Teenagers are funny.

Now, as a new parent, Walmart is a cathedral. It has high ceilings, lots to look at, is always open, and is cheap. Lightsabers (or “laser swords,” for copyright purposes) are stuffed in boxes for the taking. Pick out a blue one, a green one, a red one. We’ll turn off the lights at home and battle in the dark. And the overall shopping experience of Walmart is undeniably kid-friendly. You can run down the aisles. You can sway in the cart. Stakes are low at Walmart. Everyone says hi to you and your sister. They smile at you. They interact. While sometimes patrons and even employees may appear, well, somewhat strange, even bearing the cross of visible ailments, they are scary and friendly. If I visit Walmart now, I leave wondering why this is. Because in comparison, I’ve noticed that at stores more canonically “upper class,” you kids turn invisible. No one laughs at your antics. No one shouts hello. No one talks to you, or asks you questions. At Whole Foods, people don’t notice you. At Stop & Shop, they do. Your visibility, it appears, is inversely proportional to the price tags on the clothes worn around you. Which, by the logical force of modus ponens, means you are most visible at, your very existence most registered at, of all places, Walmart.

Eric Ravilious

Is life a simulation?

Hint: no. And why this kind of talk is built on a category error

From Indy Johar

The dominant metaphysical conceit of our time is not the belief that we inhabit a simulation. It is the conviction that we could construct one.

That with sufficient data, compute, and synthetic cognition, we might simulate a universe indistinguishable from our own. That we might birth a General Artificial Intelligence capable not just of matching, but of exceeding the intelligence embedded in this reality.

This is not science fiction — it is the guiding mythos of much of our contemporary technological ambition.

But this ambition is founded on a profound category error.

The Delusion of Extracted Intelligence

At the core of the simulation hypothesis — and the broader AGI dream — is the implicit belief that intelligence is extractable.

That cognition is a substrate-independent phenomenon. That mind can be decontextualized from matter. Encoded, digitized, and run on silicon.

This is the Cartesian inheritance, repackaged in machine form:

That thought exists apart from the world, and that the world can be reconstructed from its informational residues.

But what if this is backwards?

What if intelligence is not a modular function that can be abstracted from context?

What if it is relational, emergent, situated — not within a substrate, but within a process?

The Universe Is Not a Dataset

To presume the possibility of simulation is to treat the universe as a knowable object — a bounded system that can be compressed into a model and reconstructed through formalism.

But the universe is not a dataset.

It is not a finite body of information waiting to be mined, parsed, and rendered.

It is a recursive, entangled, multi-agent unfurling — a process of ontogeny, not ontology.

And if the universe is itself a kind of computation, it is not one we can simulate — because we are already inside it.

To simulate it from within is tautological.

To simulate it from outside is impossible.

This is not a technical limitation.

It is an ontological boundary condition.

No system can fully contain a simulation of itself — not because of processing constraints, but because simulation presupposes separability, and the universe does not grant us that luxury.

Ambition as self-sabotage

I learned this lesson a long time ago when I realised that dividing the work for an essay into ‘reading and research’ and ‘writing’ was dumb, that they need to guide each other. But still find it hard to live by.

There is a moment, just before creation begins, when the work exists in its most perfect form in your imagination. It lives in a crystalline space between intention and execution, where every word is precisely chosen, every brushstroke deliberate, every note inevitable, but only in your mind. In this prelapsarian state, the work is flawless because it is nothing: a ghost of pure potential that haunts the creator with its impossible beauty.

This is the moment we learn to love too much.

We become curators of imaginary museums, we craft elaborate shrines to our unrealized projects... But the moment you begin to make something real, you kill the perfect version that lives in your mind.

Creation is not birth; it is murder. The murder of the impossible in service of the possible.

the curse of vision

We are perhaps the only species that suffers from our own imagination. A bird building a nest does not first conceive of the perfect nest and then suffer from the inadequacy of twigs and mud. A spider spinning a web does not pause, paralyzed by visions of geometric perfection beyond her current capabilities. But humans? We possess the strange gift of being haunted by visions of what could be, tormented by the gap between our aspirations and our abilities.

This torment has a name in cognitive science: the "taste-skill discrepancy." Your taste (your ability to recognize quality) develops faster than your skill (your ability to produce it). This creates what Ira Glass famously called "the gap," but I think of it as the thing that separates creators from consumers...

my favorite anecdote… "the best is the enemy of the good"

In a photography classroom at the University of Florida, Jerry Uelsmann unknowingly designed the perfect experiment for understanding excellence. He divided his students into two groups.

The quantity group would be graded on volume: one hundred photos for an A, ninety photos for a B, eighty photos for a C, and so on.

The quality group only need to present one perfect photo.

At semester's end, all the best photos came from the quantity group...

The quantity group learned something that cannot be taught: that excellence emerges from intimacy with imperfection, that mastery is built through befriending failure, that the path to creating one perfect thing runs directly through creating many imperfect things.

your brain, it turns out, is an exquisite liar

When you imagine achieving something, the same neural reward circuits fire as when you actually achieve it. This creates what neuroscientists call "goal substitution"—your brain begins to treat planning as accomplishing. The planning feels so satisfying because, neurologically, it is satisfying. You're getting a real high from an imaginary achievement...

The aspiring novelist who spends months crafting the perfect outline gets the same neurological reward as the novelist who spends months actually writing. The brain can't tell the difference between productive preparation and elaborate procrastination.

the quitting point

Here's what happens to those brave enough to actually begin: you discover that starting is only the first challenge. The real test comes later, at "the quitting point" —that inevitable moment when the initial excitement fades and the work reveals its true nature...

This is the moment that separates the quantity group from the quality group: not at the beginning, but in the middle, when the work stops being fun and starts being work.

The quitting point is the moment you discover whether you want to be someone who had a great idea or someone who made something real.

lower the stakes!

Counterintuitively, the path to creating your best work often begins with permission to create your worst.

When you lower the stakes, you enter into a conversation with reality. Reality has opinions about your work that are often more interesting than your own... Reality is the collaborator you didn't know you needed.

Your masterpiece won't emerge from your mind fully formed like Athena from Zeus's head. It will emerge from your willingness to start badly and improve steadily. It will emerge from your commitment to showing up consistently rather than brilliantly. It will emerge from your ability to see failure as information rather than indictment...

We are still the only species cursed with visions of what could be. But perhaps that's humanity's most beautiful accident. To be haunted by possibilities we cannot yet reach, to be driven by dreams that exceed our current grasp. The curse and the gift are the same thing: we see further than we can walk, dream bigger than we can build, imagine more than we can create.

And so we make imperfect things in service of perfect visions. We close the gap between imagination and reality one flawed attempt at a time.

Tucker and Jordan

Academia: another scandal

Academia is beset by problems. They are problems that could be worked on. They’re talked about, but not seriously worked on because, as I suggested in this piece, they relate to the public goods of academia - p-hacking, publication bias, the gaming of metrics and the inherent risk aversion engendered by peer review. And public goods require collective action. But to a really remarkable extent, universities are so busy competing that they don’t attend to these problems seriously. It doesn’t surprise me that most universities do this. But it does surprise me that there’s not a vibrant minority trying to do better. Some might be minor universities in lovely places to live. They might attract some really good academics. And mightn’t one of those approximately 20 American universities with over $5 billion in endowments use them to buck the system? But I can’t say I’m holding by breath. Anyway, here’s another obvious problem that has been around for decades.

When you write about higher education, there's always a rock to turn over and there's always a scandal under the rock. Here's one: standard textbooks (including digital editions) for introductory science courses are anywhere from 8-20 years out of date. Here's another: this fact is widely known and accepted by science educators.

In the humanities, outdated textbooks provoke outrage, op-eds, tumultuous school board meetings, strong positions, legislation. So I wondered why nobody protests old science books at the high school or college level. Meanwhile, the U.S. is falling behind globally in science innovation. Just 40% of U.S. students who intend to major in STEM actually complete the degree, a startling attrition rate that begins in first-year science classes...

The reason you will not find a definitive link between outdated textbooks and poor STEM outcomes is that the public conversation is focused almost entirely on cost, not content. Major studies compare high-cost commercial textbooks to free Open Educational Resources (OER), without noticing that both have a "strikingly similar design," and contain identical content...

The textbook industry vs. science news

The science textbook industry is a broken oligopoly, or perhaps cartel. Its (profitable, messy, inefficient) business model relies on high prices and superficial revisions designed to kill the used book market. Free open textbooks are all versions of their expensive commercial counterparts...

Meanwhile even when cost is solved, introductory courses are failing to excite students and attrition rates in STEM remain high. The pedagogical focus shifts to "active learning" or "belonging" rather than to the excitement of new scientific discoveries...

In short, science textbook stagnation is everyone's fault and nobody's.

AI is poised to jump-start science education by bypassing the entire chain of intermediaries. It can analyze the latest scientific papers directly, delivering the excitement of discovery to students without the filter of textbook publishers...

What is missing from college introductory science courses?

Physics course materials often lag the furthest behind, following a century-old progression from mechanics through electromagnetism. Textbooks still teach semiclassical models, like the Bohr model, that faculty who have the time spend "unteaching" to their students...

Standard chemistry materials, even in top universities, still follow the general-organic-physical pathway. While advocates have succeeded in integrating "green chemistry" into introductory courses, transformative fields like nanotechnology are almost entirely absent.

Biology shows a similar decades-long lag in integrating major discoveries. Recombinant DNA techniques developed in the 1970s didn't appear in undergraduate textbooks until the 1990s...

Outdated science as business model

The acceptance of outdated science is rooted in the 20th-century scaling of higher education. After WWII, the GI Bill and a push for "general education" created a massive market for standardized textbooks...

This legacy of tolerance for the outdated persists, which we should all find very odd. Today, a science textbook can be seven years old and still be acceptable for transfer credit in the University of California system...

AI will make this scandal impossible to ignore

Universities can no longer defend a business model where students pay tuition for a human to deliver information that an AI can personalize for each learner instantaneously. Once AI can deliver the entire general education curriculum, the university's value proposition must shift from introducing students to knowledge to guiding students at the frontier of knowledge...

Teaching at the frontier is expensive. It is the opposite of the scalable, one-size-fits-all model that defines general education. Faculty are already too burdened by state-mandated learning outcomes and assessments that measure absorption of old knowledge...

An undergraduate education should be organized around three questions: What do we know? How do we know it? And what remains unknown? This pedagogy cannot be done at scale...

If U.S. universities are to remain competitive, students must work at the frontier. It is the only part of education that cannot be automated, and the only thing worth the price of tuition.

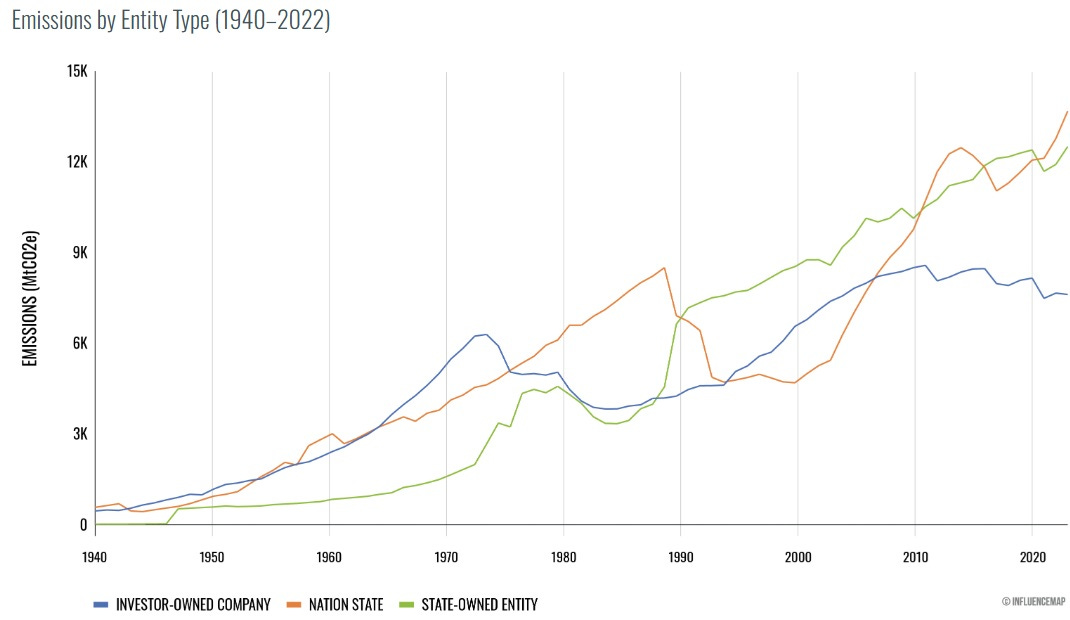

Climate change disinformation from the left: shock!

Joseph Heath’s complains about left wing disinformation on climate change are worth reading. But as I read them, I couldn’t help thinking about something more fundamental. Blaming the 100 ‘major emitting’ firms for 70% of emissions isn’t just misleading when it’s used to suggest that those firms are privately owned. It completely papers over the real problem which is that people’s enthusiasm for reducing emissions has a very nasty tendency to slide precipitately when they get asked to pay the costs of doing so.

As costs are imposed on private emitters, it’s true they’ll try even harder to improve their carbon efficiency. However most of the action will be in passing increased costs onto their customers or reducing production - which will also impose costs further downstream. As that happens, the left wing messaging of ‘corporations bad, people good’ breaks down. The people are not particularly good, but they like the game in which they are. (Just as they like playing the ‘politicians bad, people good’ game of democracy even though those politicians who didn’t tend to spin to their electorates got weeded out - got voted out of the game by us voters - generations ago.

Anyway, over to Joseph and his technicolour complaints.

I have a professional interest in the philosophical issues raised by the problem of global climate change. I wrote a book on the subject, I give lectures, attend conferences, speak on panels, etc. Yet I often find these events quite frustrating, for reasons that some may find surprising. On many of these occasions, instead of being able to focus on the genuinely difficult philosophical questions raised by climate change (involving primarily the way that we think about our obligations to future generations) I find myself dedicating a large fraction of my time to correcting misinformation. To be clear, these are mistaken beliefs held, not by members of the general public, but often by other university professors.

Everyone knows that misinformation is a serious problem when it comes to debate over the climate change issue. The UN just released a major report on the subject. The report, unfortunately, follows the general trend of focusing exclusively on right-wing disinformation, while ignoring completely the possibility of left-wing disinformation. More specifically, it focuses on climate denialism and skepticism (i.e. views that downplay the severity of the problem) while ignoring the opposite tendency toward catastrophism (i.e. views that radically overstate the seriousness of the problem)...

There is a temptation to give the latter a free pass, on the grounds that we are not currently doing enough to mitigate climate change, and so erring on the side of overstatement, when it comes to presenting the anticipated consequences, seems harmless. Where this attitude becomes a serious problem, however, is when people start to call for regulation, or criminalization, of climate misinformation...

To get a sense of what I mean when I say "left-wing climate misinformation," consider the role that The Guardian has played in propagating the (false) claim the over 70% of emissions are produced by only a small number of corporations. This claim has its origins in the Carbon Majors Database, which tracks the emissions produced by "the world's largest oil, gas, coal and cement producers." The word producers is key here, because the report includes both public sector and private sector emitters. Yet The Guardian reported these figures under the following headline: "Just 100 companies responsible for 71% of global emissions, study says." If one reads the article carefully, one will discover that investor-owned corporations are responsible for less than half of these emissions, and that of the top 10 emitters, only two of them are private corporations...

I call this sort of thing "highbrow" misinformation not just because of the social class and self-regard of those who believe it, but also because of the relatively sophisticated way that it is propagated. Often one will find the accurate claim buried deep in the text, but framed in a way that leads most readers to misinterpret it...

[This leads to ineffective policy recommendations, like activists calling for nationalization of fossil fuel companies without realizing state-owned enterprises are already the largest emitters.]

Anyhow, all of this is just a warmup for the issue that I want to discuss, which involves what I think must be the most common piece of highbrow climate misinformation. A very large number of people believe that climate change, under the high-probability "loss and damage" scenarios, within the next few decades, stands poised to lower the standard of living of future generations below what it is today.

Of course this may happen, but it is absolutely not what any of the studies say, or what the IPCC loss and damage reports say. The misrepresentation stems from the way that these studies present their results and how those presentations subsequently get reported.

Consider, for example, the following opinion piece, which I came across in the Globe and Mail last year: "Climate change will knock one-third off world economy, study shows."... Saying that the economy will "contract" clearly implies that we are talking about a net decrease in GDP, like during a recession. Similarly, the idea that one might "knock one-third off" of the world economy suggests that people in the future will be poorer than they are today. But this is not what the study claims.

In order to figure this out, however, one must read the study quite carefully... What the authors are saying is that, rather than just the expected increase of 100% between now and 2050, the world economy could be increasing by 119% if there were no climate change. In this respect, climate change will "decrease" output by 19%.

Of course, many people will choose not to believe these projections about GDP growth... The observation that I am making here is the much narrower one – that the results of this study are being misreported and misunderstood, which is causing the average educated person to have false beliefs about the assumptions that structure environmental policy debates...

All of the confusion and misinformation on this issue interferes with my work, because one of the major normative challenges posed by climate change involves thinking about the tradeoffs between the short-term benefits of economic growth and the long-term harms of climate change. Furthermore, because future generations are still expected to be better off in the aggregate, by the end of the century, under the most probable scenarios, simple deontological approaches (like plain-vanilla Rawlsianism) are inadequate to address the issue...

As far as the misinformation is concerned, the important lesson to be drawn is that our epistemic environment has been severely degraded over the past decade, with the result that many traditionally trustworthy media sources have become a great deal less so. People who believe that only the right-wing epistemic ecosystem is impaired are deluding themselves. The populist right may be particularly bad, but the rot is everywhere.

Good piece

Heaviosity Hannah

This week’s heaviosity half-hour is perhaps rather more than a half hour - consisting of three related pieces.

What is Arend’s Amour Mundi?

This Samantha Rose Hill on Hannah Arendt’s hostility to sentimentalism, though I’ve edited out Hill’s leaning into her own ideological sentiments.

Readers looking to Arendt’s Amor Mundi [love of the world] for a form of political love might at first be disappointed. Amor Mundi—love of the world—is not love in any sense we’re commonly used to. There is, however, a challenge to think about what it means to be committed to the world, to care for the world despite its horrors. There is a provocation to embrace one another in our difference and to meet one another as fellow human beings. There is also a radical critique to be found of more common forms of love, which are destructive of difference and plurality.

Arendt’s conception of Amor Mundi has more to do with understanding and critical thinking than with sentiment or affect. For her, love cannot be political. It is dangerous and destructive to the realm of political affairs. Throughout her work, Arendt discusses numerous forms of love: eros, philia, agape, cupiditus, caritas, fraternitas. But love and politics is dangerous terrain.

In her treatise on The Human Condition, which she intended to title Amor Mundi, she writes:

“Love, by its very nature, is unworldly, and it is for this reason rather than its rarity that it is not only apolitical but antipolitical, perhaps the most powerful of all antipolitical forces.”

Love of the world is also not the same as equality or care, or extending oneself to another from a place of need. In a letter to Auden Arendt chastises his characterization of charity and forgiveness as a form of love, writing that:

“You talk about charity as though it were love, and it is true that love will forgive everything because of its utter commitment to the beloved person. But even love violates the integrity of the wrongdoer if it forgives without having been asked to.”

Love in this sense is not the same as forgiveness, because love is not capable of critical thinking and judgment—it 'violates the integrity of the wrongdoer,' flattening all wrongs to a plane where each can be forgiven. In another letter to James Baldwin Arendt also criticizes his understanding of political love:

What frightened me in your essay was the gospel of love which you begin to preach at the end. In politics, love is a stranger, and when it intrudes upon it nothing is being achieved except hypocrisy. All the characteristics you stress in the Negro people: their beauty, their capacity for joy, their warmth, and their humanity, are well-known characteristics of all oppressed people. They grow out of suffering and they are the proudest possession of all pariahs. Unfortunately, they have never survived the hour of liberation by even five minutes. Hatred and love belong together, and they are both destructive; you can afford them only in private and, as a people, only so long as you are not free.

The love that belongs to the oppressed makes the injustices they suffer bearable. And when this love, with its empathy and commitments to justice and equality, enters the public realm it becomes destructive of plurality, which is the foundation of democracy. For Arendt there is a distinction between solidarity, which is the acceptance of difference and welcoming of plurality, and empathy and equality, which seek to flatten and condense. Baldwin’s idea of love can only ever threaten the political by leading us away from democracy.

Love of the world is about understanding and reconciling one’s self with the world as it is. Or, to use Arendt’s own language, it is the idea that we must “face and come to terms with what really happened”, and what is happening today. How can we live in a world where something like the Holocaust is possible? In her letter to Karl Jaspers written on August 6, 1955, Arendt says:

“Yes, I would like to bring the wide world to you this time. I’ve begun so late, really only in recent years, to truly love the world that I shall be able to do that now. Out of gratitude, I want to call my book on political theory ‘Amor Mundi.’”

This passage comes in the middle of the letter, where Arendt is describing the “melancholy task” she’s been working on—writing introductions for books by two deceased friends, Hermann Broch and Waldemar Gurian. It is only because of her love of the world that she is able to perform this one last act of friendship. Within this statement there is a recognition and reckoning with the events of the past. What does it mean to love the world in face of such great loss?

For Arendt, Amor Mundi is bound up with her axiom at the beginning of The Human Condition that we must stop and think what we are doing, along with the idea of reconciliation that is threaded throughout her thinking journal and her essays on responsibility and judgment. There is a form of self-reflective critical thinking contained within these ideas, since in order to see the world as it is we must stand on the sidelines, find perspective, and a place of solitude for thinking. In other words, there has to be a turning in before we can turn out. Loving the world requires reckoning with the world, which means we must find some critical distance from what is happening around us. When we witness injustices, sometimes there is an impulse to act, but Arendt cautions us to slow down and think what we are doing—to be thinkers not just joiners.

This form of reckoning and reconciliation might also be understood as making peace with one’s self; finding a way to have fidelity to one’s thoughts even in our darkest moments of loss, grief, and crisis. Amor Mundi can give us a metaphysical sense of certainty in a world that is always being destroyed. It is a relational form of love.

In earlier letters to Jaspers Arendt talks about the joy she finds in the American people—a young fishmonger who has read all of Jaspers’ work, a young girl from a poor family whose living room is filled with books of Plato, Hegel, and Kant. Loving the world involves reconciling ourselves with the events of the past so that we can move about the everydayness of life, to go on living, to create, to find joy, to find perspective, to build new friendships, and to remind ourselves of where the possible remains—in language, in poems, in the young fishmonger who has a fondness for philosophy. It’s a promise of continued existence, a way of not resigning from the world when the world seems too unbearable to live in.

What kind of world are we facing today? Why is public funding being allocated to walls instead of arts? Why are so many Americans unable to afford health insurance? Why do we value some lives more than others? And why are middle-aged Americans committing suicide at unprecedented rates?

More broadly, how is there genocide in the 21st century? Why are we experiencing the largest refugee crisis since the Second World War? Why do we keep insisting on the rhetoric of social equality instead of learning to appreciate and celebrate our differences? And why do we demand answers to any of these questions when the logic of question-answer is the same logic of tyrannical thinking?

Arendt’s conception of Amor Mundi is not comforting, it is challenging. It refuses the idea that we can ‘find meaning in’ or ‘make sense of’ and instead pushes us to work hard to understand and accept that there are no answers to these questions in the way we might wish.

In teaching us to love the world Arendt is teaching us to be thinking, engaged citizens. She cautions us against the impulses of sentiment or affect, and guides us toward political thinking. Loving the world offers us a way of being in the world that plants our feet firmly in reality, so that we can see what is before us.

How to Think—and How Not to Think—About Race

I’ve really enjoyed listening to this book which I recommend. This excerpt is from Chapter 5. It’s followed by the contemporary source on which much of the latter part of the extract is commenting.

Race is, politically speaking, not the beginning of humanity but its end, not the origin of peoples but their decay, not the natural birth of man but his unnatural death.

—Origins of Totalitarianism

Hannah Arendt wrote to James Baldwin out of a strong political identification. [See the quote in the previous extract above.] Love is the privilege of pariah peoples as long as they are not free, she told him. She knew this herself from Berlin, from Paris, from Gurs, and from Montauban. Three years earlier, in 1959, she had published an essay called “Reflections on Little Rock.” There she criticized the campaign against the segregation of schools in the Jim Crow South. It was wrong and cruel, she argued, to put children in the front line of the struggle against racism. She did not say so explicitly, but she also assumed she knew this herself from her own childhood, and from her work with Jewish children in Paris. But Hannah Arendt did not know the children of Little Rock, Arkansas, nor did she comprehend the history of their fight. Written in a lofty and chiding tone, her essay caused a scandal because in it she had forgotten one of her own lessons: you can’t co-create rights and freedom with people who you cannot see.

To think about race alongside Hannah Arendt often also means thinking against her. On the one hand, she is an original and powerful historian of modern racism. By the time she arrived in New York in 1941, her pariah perspective was pretty much fully formed. Over the next thirty years she would find new ways of putting this perspective into writing. The Origins of Totalitarianism came first in 1951, followed by The Human Condition, her love song to the world, seven years later. She picked up the historical threads of terror and freedom in On Revolution, published in 1963, the same year that her most audacious reckoning with totalitarian thinking, Eichmann in Jerusalem, catapulted her into public consciousness. In each of these books she pitched plurality against terror and tyranny and the human condition against racist and inhuman ideologies. But her “Little Rock” essay would not be the only occasion on which she would fail to comprehend American racism and Black resistance to it. Commentators have noted that her enthusiasm for America’s democracy blinded her to its white mythologies. This is certainly true, but that blindness means that something else sometimes bubbles up when she writes about race. Hannah Arendt was a principled anti-racist thinker, but this did not mean that she always thought well about race. …

Famous as one of the first and certainly most original studies of a new political phenomenon, The Origins of Totalitarianism is also a survivor narrative told by a refugee determined to document the historical conditions of her uprooting. No wonder it was passionate and unwieldy. How do you tell the history of your own near disappearance? This huge and sprawling text was Hannah Arendt’s most ambitious affirmation yet of her own life. I sometimes think of it as an act of love disguised as scholarship.

Upon publication, she was both praised and criticized for her passion. The Times Literary Supplement condemned her “tortured and self-torturing sincerity.”[1] Others accused her of sentimentality and of lacking sufficient academic disinterestedness. She retorted that her subject called for a stylistic approach that was as quietly outraged as totalitarianism was itself outrageous. Anything else would be a denial of what had really happened.

The book’s status as a classic of Cold War thought has also obscured the extent to which it is, among other things, a study of modern racism. In fact, the bulk of the book is concerned with this history. She had started the research for the first section, “Antisemitism,” in Berlin and Paris. Religious discrimination against Jewish people had evolved into an ideology of race hatred over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (I was there to see the end of this, she might have added). In the second section, “Imperialism,” she traced how French and British imperialism had ransacked Africa and India using ideologies of racial supremacy as both a pretext and a justification. When Germany, Austria, and Russia then turned imperial racism on Europe itself, the elements that would eventually crystallize into totalitarianism moved into place. The elementary structure of totalitarianism is the hidden structure of the book, while its more apparent unity is provided by certain fundamental concepts which run like red threads through the whole, she explained.[3]

One of those red threads, perhaps the red thread, was racism and race-thinking. That thread also ran through the politics of the country in which she now wrote. Adolf Hitler had approvingly referenced the oppression of Black Americans in the Jim Crow South. Many whites in America had just as approvingly referenced him back in the 1930s and early 1940s. Just because they had now gone quiet did not necessarily mean they had changed their minds.

In its early stages, the now hidden structure of the book, along with Arendt’s fevered outrage, was much more explicit. She planned to call it The Elements of Shame: Anti-Semitism-Imperialism-Racism. I like “shame” because it captures her belief that such a profound moral line had been crossed that people could barely bring themselves to speak of it. The ashamed are usually silent, as well they might be in this case: Arendt’s elements of shame were anti-semitism, imperialism, and racism, none of which had vanished from the face of the earth with the defeat of Nazism. Another, more Dante-esque early title was The Three Pillars of Hell: Anti-Semitism-Imperialism-Racism. Right up until the proof stages the working title was The Burden of Our Time: Anti-Semitism-Imperialism-Totalitarianism (this was also the title of the first UK edition). Arendt had now grasped how anti-semitism and imperialism were the elementary structures from which totalitarianism would eventually emerge. The Burden of Our Time, taken from her poem about walking alongside the Hudson with Blücher, is a reminder of how deeply personal this book about inhuman and profoundly impersonal political structures was.

The word “totalitarianism” didn’t find its way into the main title until just before the book went to press in the autumn of 1950. It was her US publisher that suggested The Origins of Totalitarianism. It is a great title and it was a shrewd move to keep an explicit mention of racism and anti-semitism off the front cover. In 1951, many Americans would have been reluctant to think about either as one of the key elements of a political system that was supposedly the antithesis of their own democracy. Far better to get those readers into the book first.

But the muting of racism, imperialism, and anti-semitism had consequences for how the book was, and is, read. The final, and now most read, section of the book, “Totalitarianism,” is a terrifying and exhilarating account of a political system in which human spontaneity has all but been eliminated. Death and horror stalk these pages as Arendt brilliantly adumbrates how ideology ripped apart people’s experience of the world, bearing down on minds and smashing through laws and institutions with a relentless dark energy, culminating in the death camps and gulags. This was the nightmare of “total domination” that had now arrived in the world and which she feared was here to stay, although possibly not in such a dramatic and extreme form. Tired horror, she would go on to say, can be just as, if not more, morally corrupting than the vivid violence of pure terror.

Yet it was implicit in Arendt’s argument that the elements that eventually produced totalitarianism are endemic to most modern political systems. It’s not just massively outsize propaganda, unspeakable terror, constant surveillance, fear, censorship, black flags, concentration camps, and public executions you need to watch out for. Racism, political and economic greed were all there at the beginning too. They were the roots.

The first modern superfluous people, Arendt argued, were created by the desire for superfluous wealth. If you want to understand the origins of totalitarianism, look to the origins of Empire. “I would annex the planets if I could,” the English vicar’s son, mining magnate and whiteness ideologue Cecil Rhodes declared at the height of his mission to turn Africa’s resources into pure wealth and its people into the pure labor necessary to produce it. He was totally serious. Arendt opened the middle section of her book, “Imperialism,” with Rhodes’s mad quote. Much of what followed aimed to take him and everything his deranged ambition stood for down. (I think of Rhodes’s words whenever I hear the business mogul Elon Musk detail his plans for annexing the planets as a “solution” to the climate catastrophe.)[4]

Another Englishman, George Orwell, so often in lockstep with Arendt, had earlier made the point, well known throughout Asia and Africa, that human rights were not first demolished in Europe in the middle of the twentieth century but at least a hundred years earlier. What was the freedom the West was fighting for? he asked in 1939. Just whose lives were being counted in the name of white democracy? Lying under anybody’s nose were many of the elements which gathered together could create a totalitarian government on the basis of racism, Arendt wrote of British imperialism. “Administrative massacres” were proposed by Indian bureaucrats while African officials declared that “no ethical considerations such as the rights of man will be allowed to stand in the way” of white rule (OT 286).

The vivid novelty of the third section of her book, “Totalitarianism,” eventually overshadowed much of the historical material that preceded it and left the impression that the horrors of imperialism in Africa and India were simply building blocks for a greater horror—the “greater” horror being that its murderousness now extended to white people too. The reason why Europeans were so appalled by Hitler, wrote the Martinique poet and politician Aimé Césaire in Discourse on Colonialism, first published in Paris a full year before The Origins of Totalitarianism, was because he “applied to Europe colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively” for people in Algeria, Africa, and India. …

Thirty-six years after Hannah Arendt ran through the streets of Königsberg, another smart fifteen-year-old girl, books clasped close to her heart, was trying to find her way home. She, too, was thoughtful and serious. She also sometimes seized the time walking from school to home or from home to the shops or back from church to lose herself in thought and disappear. But because she lived in Little Rock, Arkansas, the moments when Elizabeth Eckford could slip inside herself were few and precious. She was rarely allowed to forget that she was appearing for others; that she was a Black girl walking alone in the Jim Crow South.

On the morning of September 3, 1957, Elizabeth Eckford was not only fighting for her mind, she was fighting for her life. In case she was in any doubt about this, the mob of white youths surrounding her told her so; specifically, they screamed, they would like to lynch her. She knew that the State of Arkansas would not protect her because when she had walked up the steps of Central High School just a few minutes before, it was against her body that the National Guard had raised their bayonets. In the five more minutes it took her to walk back down the steps, through the grounds, and out into the street, she also discovered that if you appeal for help with your eyes, as children do, to the nearest adult woman with a kind face, if that woman is white what you might get in reply is her spittle on your cheek. Understanding all of this, she knew she must keep walking at all costs, which she did, eyes behind her sunglasses, the layers of tulle petticoat under the special dress she had stayed up late making the night before camouflaging the knees trembling beneath them.

The photographs taken of Elizabeth Eckford’s long walk from the school steps to the bus stop were reproduced across the world. Nobody could fail to see what happened when a young Black woman claimed her rights and walked alone in the South. As the Eckford family had no telephone, she did not get the message saying that the police would escort the children to school on that first day, so she had gone by herself. The cab firm she was led to by the activist Grace Lorch refused to take her home. The journalists who encircled her, tall, suited, grown white men, kept the mob from getting to her but still flashed their cameras in her face, demanding to know her name, what she thought she was doing, and how afraid she really was. One of them, Benjamin Fine, sat next to her on the bench by the bus stop, put his arm around her, and whispered firmly: “Don’t let them see you cry!” “This little girl, this tender little thing, walking with this whole mob baying at her like a pack of wolves,” he later wrote.[10] Elizabeth Eckford did not let them see her cry. She shut herself up tight and waited for the bus to take her to the school for the deaf where her mother worked.

Everyone was interested in Elizabeth Eckford, but in another sense, hardly anybody was interested in her. For all the demands made on her that day and since, few white observers at least troubled themselves to ask the one question, according to Hannah Arendt in The Human Condition, that must be asked of every newcomer—and every changemaker—in a truly plural world: Who are you? What do your actions and speech—your agency—tell us, who share the world with you, about you?

Certainly not Hannah Arendt herself, aged fifty-one, now an established public intellectual in her new home, who watched the events unfolding in the South from New York with unease. I think no one will find it easy to forget the photograph reproduced by newspapers showing a Negro girl…persecuted and followed into bodily proximity by a menacing mob of youngsters, she wrote in her essay “Little Rock,” which was originally intended for the Jewish magazine Commentary. Arendt looked at Eckford and saw a little girl, an achingly vulnerable little Negro girl. Have we now come to the point where it is the children who are being asked to change the world? And do we intend to have our political battles fought out in the school yards? she despaired.[11] The answer to both those questions, as the Little Rock Nine and countless other civil rights activists would go on to demonstrate in the months and years that followed, was yes.

But that was not the answer Arendt wanted. In prose Ralph Ellison, author of Invisible Man, would describe as “Olympian” (which he did not mean as a compliment), she argued that education was the wrong battle to fight segregation with. The photographs of Eckford and the mob of white teens, she admonished, were like the worst caricature of progressive education, where the adults had divested themselves of all responsibility and left Black children to the mercy of the pack and those in the pack to their worst instincts. Elizabeth Eckford had been failed, by her community, by the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), and, she suggested, in a truly scandalous piece of insensitivity, by her parents.

In the days leading up to September 3, Elizabeth Eckford’s mother, Birdie Eckford, had talked over the risks of sending her daughter to school with the editor and journalist Daisy Bates, the president of the Arkansas NAACP. Mrs. Eckford recalled walking as a child with her own mother and witnessing a lynch mob dragging their victim through the streets of Little Rock: “We were told to get off the streets. We ran. And by cutting through the side streets and alleys, we managed to make it to the home of a friend. But we were close enough to hear the screams of the mob […] to smell the sickening odor of burning flesh. And, Mrs. Bates, they took the pews from Bethel Church.”[12] Both women knew that what they had to fear for their children went far beyond the supposed anarchy of progressive education. Hannah Arendt was not seeing this—or Elizabeth Eckford—right.

Commentary spiked her article. On September 23, President Eisenhower ordered the 101st Airborne Division into Little Rock and on the 24th the Nine finally walked through the doors of Central High. For the rest of the school year, they battled regular physical and psychological abuse. In the summer of 1958, Governor Faubus made one more effort to delay desegregation and succeeded in shutting down the entire school system for a year. The Nine, their advocates, and the local school board dug in for a long fight.

Surprisingly, so too did Hannah Arendt and published her article in another magazine, the left-leaning Dissent, a full year after she had first written it. The predictable outrage was immediate. Not only had she gone too far, but many also found it hard to see where she had gone at all. For most people, at least in the North, the case for desegregation was self-evidently just. If anybody was irresponsible it was a nation that permitted some of its children to believe they were less worthy of educating than others. The harm done to the self-esteem of Black children by segregation had been demonstrated in recent and much-publicized studies that had helped to galvanize liberal opinion and steel the resolve of activists. To argue against the desegregation of schools was monstrous.

Arendt based her case on two arguments. The first was a concern about equality, visibility, and social rights. Anticipating worries in the early twenty-first century about how successful progressivism provokes conservative backlashes, Arendt fretted that compulsory school desegregation risked providing white rage with a phony justification. White resistance to Black people becoming visible agents of political power was probably inevitable, she thought, although it didn’t have to be that way. The rise of Trumpism in America would not have surprised her. What scared her in 1957, as it scared many between 2016 and 2020, was the anti-political senselessness of that rage. Why risk triggering a mob mentality that threatened the wider project of political equality? she asked. And why do that while leaving fundamental human rights violations—specifically southern state laws that prohibited interracial sex and marriage—intact? If social prejudices are to be prevented from becoming tyrannical, maybe we should allow people to have their differences and discriminations, even if we find them repellent?

Arendt’s experience of Nazism made her hyper-alert to the dangers of one-size-fits-all social solutions. Her migrant experience of American mass society made her warier still. Social conformity was one of the first things she noticed about her new home. The fundamental contradiction of the country is political freedom coupled with social slavery, she wrote to Karl Jaspers in January 1946 (AKJ 30). When she’d first arrived in the United States, Arendt had been taken in as part of a refugee hosting scheme by a couple in Massachusetts. The deal was that she would help with the housekeeping in exchange for English lessons. Hannah Arendt, unsurprisingly, was the worst au pair and the most interesting of houseguests. She did next to no housework or cooking (although she would maintain throughout her life that she was an expert cook, privately her friends differed on this matter). She preferred to stay up late talking politics with her hosts, particularly with the husband; she couldn’t work out whether they were Jewish or not, but suspected there was a story. She was deeply impressed by how naturally the couple took responsibility for local and national issues; attending meetings and writing to legislators exactly as though what they did should, and indeed would, make a difference. People did not behave like this in Europe. Was this perhaps political freedom in action?

But what then puzzled her was that such a politically engaged people could also be so socially conservative. The right to have rights was there, in theory, waiting to be grasped, but the mood was low-key and socially stifling. Arendt wasn’t simply being an Old World snob. She had the nineteenth-century French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville’s famous observation about the paradox of American democracy in the back of her mind. Democracy gives people a singular and precious power, but the tyranny of the majority always threatens. In a democratic republic committed to equality, such as the United States, it does not take much for the demand for social equality, even equality in misery and oppression—social slavery—to exert its pressure. In other words, democracy is no guarantee of political or personal freedom. As the writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie succinctly paraphrased this paradox in 2022: “We fear the mob, but the mob is us.”[13]

The tyranny of the mob does not just belong to fascist and totalitarian societies. It is there too in social democracies. Arendt believed deeply that once people become their own secret police, politics really starts going to the bad. Social media, she might have said, is merely the latest example of how what might look like social liberty can also breed a dangerously oppressive conformity. Few nowadays need lessons in how the internet can raise a mob. We can name and shame, follow and unfollow, but we need to remember that as we do, real political and economic power remains in the shadows. One of Arendt’s key historical lessons for today is each to their social own—their own clubs, Tinder accounts, parties, and dress codes—and all to fighting very hard for the political right to be different.

This lesson is at the heart of her distinction between the private, social, and political worlds. Her worry was always that both personal and political life might collapse into an over-socialized existence. In this now perhaps familiar dystopia, social conformists would dictate what you might say or not say, how you might say it, what you should have known better about, your looks, your friends, who you should be having sex with and probably how you should be having it. Morality—thinking—would never get the chance to be the topic of a two-in-one conversation enjoyed in solitude, because it would already be decided by courts of public opinion, which is to say it would be no morality at all. (“I would fear the mob less,” Adichie said, “if my neighbor would not stay silent were I to be pilloried.”) And political power would remain where it always had, with elites who are happy to let people believe they have social agency when what they actually have is merely the right to feel right, righteous, outraged, or at least not to feel despised and lonely. By contrast, freedom for Hannah Arendt meant being clear about the spaces between people, as well as acting together for a common good when it mattered.

But the Little Rock Nine were not demanding entry into a specialist holiday camp, one of Arendt’s more niche examples of the kinds of acceptable social segregation we practice all the time, any more than I would demand to be followed by the Conservative Women’s Organization on social media. They were demanding that the law be upheld and the right to the same educational privileges as their peers. They did not wish for everybody to be or to think the same as them; they wished to be young political citizens.

Ironically, the gap in Arendt’s argument was the very thing she wanted to protect: the political and personal rights of all Americans, including, most urgently, Black Americans. Her second argument in the article, about political power, was also strange in this respect. The American Republic contained the grain of anti-totalitarianism in its federated structure—this is what made it so attractive to her. Enduring political power, as the Founding Fathers recognized, was achieved by neither force nor violence but rested in the power that is created between people and associations. Where other political systems called on higher powers—God, the sovereign, History, Nature, Terror, the state—the republican tradition begins with the recognition that only the common action of people makes power durable. This doesn’t mean that people power is necessarily a good thing. Citizens can just as easily authorize their rulers to do awful things—including depriving them of their own freedoms and turning them into social slaves. But the virtue of a federated and constitutional system was that it put a system of checks and balances in place to hold power to account. It made politics human, both frail and strong—alive.

In the case of Brown v. Board of Education, she feared that the Supreme Court was putting the Republic at risk through overreach. This was a peculiar interpretation of the constitutional right to check individual states’ power to act in unaccountable ways, not to say of the Fourteenth Amendment. Even if you wanted to defend state autonomy, it’s difficult to see how you might possibly do this when, as she also pointed out, those same states were suppressing (and continue to suppress) Black votes, often using a lack of educational attainment as a bar to registration. Hannah Arendt knew all this but chose not to see it when she looked at the photographs of Elizabeth Eckford.

My first question was, what would I do if I were a Negro mother? she replied to her critics in Dissent, in a last word on the matter which even the most passionate Arendt fan must wish she had left unsaid:

The point of departure of my reflections was a picture in the newspapers showing a Negro girl on her way home from a newly integrated school: she was persecuted by a mob of white children, protected by a white friend of her father, and her face bore eloquent witness to the obvious fact that she was not precisely happy,…The answer: under no circumstances would I expose my child to conditions which made it appear as though it [sic] wanted to push its [sic] way into a group where it [sic] was not wanted.[14]

Hannah Arendt was not Elizabeth Eckford’s mother. She didn’t have to be to imagine what Birdie Eckford may or may not have done. Elsewhere, it is Arendt herself who urges the cultivation, and education, of an enlarged mentality so that we can visit other people’s experiences and look at the world from perspectives that are not our own. It is also Arendt who teaches us again and again that judgment is a matter of testing reality: of establishing the facts and dealing with them, no matter how difficult; of laying out the world as it really is, as a prelude to resisting it and making it different.

But she did not check the facts. Elizabeth Eckford was not on her way home from a newly integrated school: she was being hounded back home because the school was precisely not being integrated. Black parents, activists, and townspeople had been advised to stay away from Central High that day for fear that their presence would incite more violence, so nor was it the case, as Arendt assumed, that neither white nor black citizens felt it their duty to see the Negro children safely to school.[15] Elizabeth Eckford was not protected by a white friend of her father in the photograph; she was being shielded by white journalists. Benjamin Fine, the education editor for The New York Times who sat by Elizabeth Eckford on the bench, was a friend of Daisy Bates (although not of Mr. Eckford). “Daisy, they spat in my face. They called me a ‘dirty Jew,’ ” he later told her: “A dirty New York Jew! Get him!”[16] The National Guard responded by threatening to arrest Fine for incitement to riot; apparently being a Jewish man sitting next to a young Black woman on a public bench and telling her not to cry was reason enough to drive the white citizens of Little Rock to rip up the sidewalk.

Although she would not have been surprised to learn that the social prejudices of Little Rock’s racist mob included violent anti-semitism, Arendt did not discuss this connection in her essay. Nor did she scrutinize the personal identification that so obviously drew her to the defense, so she thought, of the children of Little Rock. Asking herself what she would have done were she Elizabeth Eckford’s mother was a way of both remembering and not remembering what it was like to be a Jewish girl walking alone in 1920s Königsberg, trying, and sometimes failing, to disappear into her own thoughts—of being denied the right to be invisible in her own unique quest to understand her world.

I should like to make it clear that as a Jew I take my sympathy for the cause of the Negroes as for all oppressed or under-privileged people for granted, she wrote in some preliminary remarks to her article.[17] But some forms of sympathy can be barriers to good political judgment. The one thing, perhaps the most important thing, Hannah Arendt’s life and writing teaches us is to take nothing for granted. Don’t assume, don’t accept, test your thoughts against reality, question—do the work. Think. But she didn’t. Hannah Arendt secretly saw herself in Elizabeth Eckford, that much is true, but it remains the case that she did not see Elizabeth Eckford. “Neither the ‘Negro girl’ nor her actions appear to Arendt,” the philosopher and poet Fred Moten has written: “Eckford is unseen because she is neither seen nor heard to see.” …

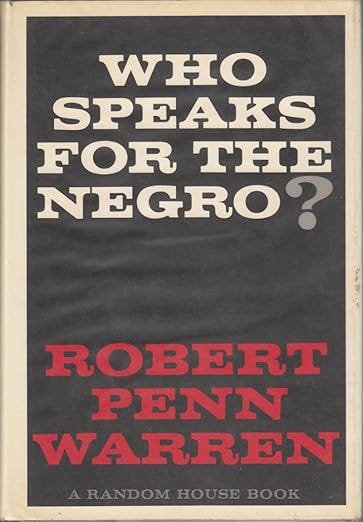

“There are no abstract rules,” the novelist Ralph Ellison once explained, describing how although all anti-racism struggles serve the same purpose, they are always unique in context. “And although the human goal of a higher humanity is the same for all, each group must play the cards a history deals them.” This, he added, “requires understanding.” He was talking with fellow southern writer and literary critic Robert Penn Warren, a regular co-contributor alongside Arendt in the pages of Partisan Review. Penn Warren had traveled across the United States in 1964, the same year that the Civil Rights Act was passed into American law, collecting interviews from leading figures, including Ellison, and local activists, which were collected in the anthology Who Speaks for the Negro?[19]

Ellison had little patience for whitesplaining northern intellectuals. “Why is it so often true that when critics confront the American as Negro they suddenly drop their advanced critical armament and revert with an air of confident superiority to quite primitive modes of analysis?” he asked in the same essay in which he had described Arendt’s prose as “Olympian”: “why is it that so many of those who would tell us the meaning of Negro life never bother to learn how varied it really is?”[20] It was exactly this brash, careless lack of attention, he explained to Penn Warren in their 1964 interview, that caused Arendt “to fly way off into left field” in her “Reflections on Little Rock” essay.

Hannah Arendt had forgotten that nobody knows more about the tyranny of social life than those who have no say in it but are compelled to exist on its terms. The people who she had once described as living without umbrellas in the rain understand more precisely because they are soaking wet. Black Americans, Ellison said, lived the truth of racism, and they were drenched.

For Ellison, understanding is “required” of minorities not out of some sense of enlightened liberal generosity toward the people who make their lives miserable, but because if you do not think all the time, if you do not constantly reflect on your place within the madness, you risk becoming the nobody, the superfluous person that racism imagines and wants you to be. Hyper-understanding is a means of survival. “This puts a big strain—yes, it puts a big strain on the individual,” Ellison told Penn Warren. “Nevertheless, isn’t this what civilization is about? Isn’t this what tragedy has always taught us?”

Tragedy teaches us that the sacrifices we make are never just individual but are meaningful precisely because we exist alongside others. When we act we make ourselves real in the world, visible, courageous even (Arendt, after Aristotle, thought that courage was the most important political virtue). When people leave their homes, take the bus, walk up to the gates, when they challenge society, they lose their privacy, expose themselves, risk everything, and they do not do this simply for themselves, because they want to be heroes (although this, too, can be the case), but out of a tacit, sometimes even unconscious, understanding of their position in relation to others. Such, at least, was Hannah Arendt’s argument in The Human Condition, the book she wrote after The Origins of Totalitarianism. If her first major book told the story of how hell was made on earth, her second was a description of the kind of political humanism that might remove it—or at least diminish its scope.

Arendt’s political heroes in The Human Condition are us: actors in the world whether we like it or not. Sometimes we are unaware of what our actions might trigger; often we’re lost in events, not knowing where the story ends. Sometimes, all we know is that we are in the story and that we must act. Although we show the world who we are through our actions, it is more than likely that the “who” which appears so clearly and unmistakably to others, remains hidden from the person himself. Action is the kind of self-expression that matters because it is understood by others (HC 181).

And this, Ellison explained in his interview with Penn Warren, was more or less exactly what Elizabeth Eckford was doing when she walked up to the gates of Central High on September 3, 1957: making a sacrifice in the tragedy that is America; being a “who” appearing for others. In this matter, neither was she as alone as she looked. “This is the thing,” Ellison explained: “my mother always said I don’t know what is going to happen to us if you young Negroes don’t do so-and-so-and-so. The command went out and it still goes out. You’re supposed to be somebody, and it’s in relation to the group. This is part of the American Negro experience, and this also means that the idea of sacrifice is always right there.”

In other words, because she could not see Elizabeth Eckford acting as a Black American living and acting among other Black Americans, Hannah Arendt did not see that Elizabeth Eckford was taking precisely the kind of walk which she herself understood as enacting the promise of politics. Back in New York, in the summer of 1965, Arendt read Ellison’s interview with Penn Warren in Who Speaks for the Negro? and for the second time in nearly as many years, stubbed out her cigarette, drew her typewriter toward her, and wrote a letter to a major Black American writer that would go unanswered:

Dear Mr. Ellison,

While reading Robert Penn Warren’s Who Speaks for the Negro I came across the very interesting interview with you and also read your remarks on my old reflections on Little Rock. You are entirely right: it is precisely the “ideal of sacrifice” which I didn’t understand and since my starting point was a consideration of Negro kids in forcibly integrated schools, this failure to understand caused me indeed to go into an entirely wrong direction. I received, of course, many criticisms about this article from the side of my “liberal” friends or rather non-friends which, I must confess, didn’t bother me. But I knew that I was somehow wrong and thought that I hadn’t grasped the element of stark violence, of elementary bodily fear in the situation. But your remarks seem to me so entirely right, that I simply didn’t understand the complexities in the situation.

With kind regards,

Sincerely yours,

Hannah Arendt

Ralph Ellison

Here is the interview to which Arendt was reacting above.

In 1952, Invisible Man was published. It is now a classic of our time. It has been translated into seven languages. The title has become a key phrase: the Negro is the invisible man.

Ralph Ellison is not invisible and had done some thirty-eight years of living before the novel appeared, and the complex and rich experience of those years underlies the novel, or is absorbed into the novel, as it undergirds, or is absorbed into, his casual conversation.

Ralph Ellison was born in 1914, in Oklahoma City, of Southern parents. His father, who had been a soldier in China, the Philippines, and in the Spanish American War, was a man of energy and ambition, and an avid reader; he named his son for Emerson. He died when Ralph was three years old, but Ralph’s mother managed to support the children and encouraged them in their ambitions.

As a boy, Ralph sold newspapers, shined shoes, collected bottles for bootleggers, was a lab assistant to a dentist, waited on tables, hunted, hiked, played varsity football, conducted the school band, held first chair in the trumpet section of the school orchestra. “Was constantly fighting,” he says, “until I reached the age when I realized that I was strong enough and violent enough to kill someone in a fit of anger.”

With some help from his mother, whom he describes as an “idealist and a Christian,” he worked his way through Tuskegee, as a music major. But there he read Eliot, and that fact, though for some years he was to keep his ambition as a composer, was the beginning of his literary career. In 1937, during a winter in Dayton, Ohio, where he had gone for the funeral of his mother (who had died, he says, “at the hands of an ignorant and negligent Negro physician”), and where he was living in poverty and making what money he could by hunting birds to sell to General Motors officials, he took up writing seriously: “This occurring at a time when I was agitating for intervention in the Spanish Civil War, my personal loss was tied to events taking place far from these shores. Thus the complexity of events forced itself to my attention even before I had developed the primary skill for dealing with it. I was forced to see that both as observer and as writer, and as my mother’s son, I would always have to do my homework.”

Ralph Ellison has traveled widely and lived in many parts of the United States; he has known a great variety of people, including “jazzmen, veterans, ex-slaves, dope fiends, prostitutes, pimps, preachers, folk singers, farmers, teamsters, railroad men, slaughterhouse and roundhouse workers, bell boys, headwaiters, punch-drunk fighters, barbers, gamblers, bootleggers, and the tramps and down-and-outers who often knocked on our back door for handouts.” He might have added that he has known the academic world and the world of the arts, has lived for two years in Italy as a Fellow of the American Academy, and has traveled in Mexico and the Orient.

* * *

Ralph Ellison is something above medium height, of a strong, well-fleshed figure not yet showing any slackness of middle age. He is light brown. His brow slopes back, but not decidedly, and is finely vaulted, an effect accentuated by the receding hair line. The skin of his face is unlined, and the whole effect of his smoothly modeled face is one of calmness and control; his gestures have the same control, the same balance and calmness. The calmness has a history, I should imagine, a history based on self-conquest and hard lessons of sympathy learned through a burgeoning and forgiving imagination. Lurking in the calmness is, too, the impression of the possibility of a sudden nervous striking-out, not entirely mastered; and too, an impression of withdrawal—a withdrawal tempered by humor, and flashes of sympathy. It is a wry humor, sometimes self-directed. And a characteristic mannerism is the utterance of a little sound—“ee-ee-”—breathed out through the teeth, a humorous, ironical recognition of the little traps and blind alleys of the world, and of the self.

His voice is not deep, but is well-modulated, pleasing. He speaks slowly, not quite in a drawl, and when he speaks on a matter of some weight, he tends to move his head almost imperceptibly from side to side, or even his shoulders.